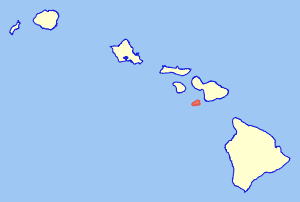

Kahoʻolawe

| Kahoʻolawe | |

|---|---|

| Satellite image of Kahoʻolawe | |

| Waters | Pacific Ocean |

| Archipelago | Hawaii |

| Geographical location | 20 ° 33 ′ N , 156 ° 36 ′ W |

| length | 18 km |

| width | 9.7 km |

| surface | 115.5 km² |

| Highest elevation | Pu'u'O Moa'ula Nui 452 m |

| Residents | uninhabited |

| main place | Hakioawa (historical) |

| North coast of Kahoʻolawe | |

Kahoʻolawe (old also Kahulaui , English Kahoolawe , Kahoʻolawe in the Geographic Names Information System ) is the smallest of the eight main volcanic islands of Hawaii . The name means "taking away (by current)" in the Hawaiian language . It is located 11.2 km southwest of Maui and southeast of Lānaʻi and belongs to Maui County . The island may only be entered with permission. There is no permanent population on Kahoʻolawe.

geography

The island is 18 km long, 10 km wide and has an area of 115.5 km². The highest point is the Puʻu ʻO Moaʻula Nui on the eastern crater rim of Lua Makika with an elevation of 450 meters . The island is relatively dry because the low elevation can produce little rainfall from the northeast trade winds. It is also in the rain shadow of the 3055 m high Haleakalā on Maui. More than a quarter of the island has been eroded into a saprolithic bedrock .

structure

Traditionally, Kahoʻolawe was an ahupuaʻa from Honuaʻula (Makawao), one of the 12 moku of Maui. Today, Kahoʻolawe is part of Makawao District , one of the six districts of Maui County .

It was divided into twelve ʻili (traditional self-government and self-sufficiency units of the lowest level), which were later combined into eight. The eight ʻili are reproduced below, in counterclockwise order, and with original areas in acres , starting in the northeast of the island:

|

With the exception of the two westernmost ʻili Kealaikahiki and Honokoʻa, their borders converge on the edge of the volcanic crater Lua Makika . The crater, however, does not belong to any of the ʻili nor is it considered an ʻili .

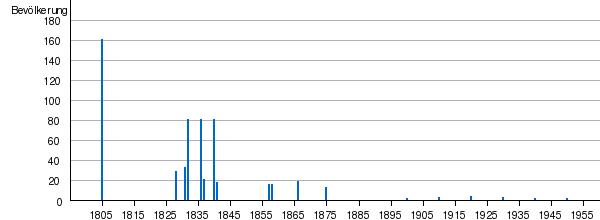

Population development

Kahoʻolawe had a larger population until the 19th century. Since the island was used as a ranch, the population has decreased significantly. No permanent population has been recorded since the 1950 census.

| 1805 | 1828 | 1831 | 1832 | 1836 | 1837 | 1840 | 1841 | 1857 | 1858 | 1866 | 1875 | 1900 | 1910 | 1920 | 1930 | 1940 | 1950 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 160 | 28 | 32 | 80 | 80 | 20th | 80 | 17th | 15th | 15th | 18th | 12 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

history

The island was settled around 1000 and small, temporary fishing communities were established along the coast. Some inland areas were cultivated using fine-grain basalt for stone tools. Originally, the country was a dry, flat forest with a few streams, which was transformed into an open savannah due to the clearing of the forest for agriculture and firewood procurement. People built stone platforms for religious ceremonies, set stones as shrines for successful fish catches, and carved petroglyphs or drawings into the flat surface of the rocks. These references to the early period can still be found today.

It is not known how many residents lived on the island, however the lack of drinking water likely limited the population to a few hundred. 100 or more people could have lived in Hakioawa, the largest settlement on the northeast end of the island.

Violent wars between competing chiefs devastated the country and led to a decline in the population. During the Kamokuhi War, Kalaniopuʻu, ruler of the island of Hawaiʻi , raided and sacked Kahoʻolawe in an unsuccessful attempt to conquer Maui from Kamalalawalu, king of Maui. From 1778 to the early 1800s, observers on passing ships reported that the island was uninhabited and barren, poor in both water and wood. Upon the arrival of missionaries from New England , the Hawaiian government was replaced by King Kamehameha III. the death penalty by exile and Kahoʻolawe became a penal colony around 1830 . Food and water were scarce. This resulted in the alleged starvation of some prisoners, which in turn led some to swim through the canal to Maui for food. In 1853 the law that made the island a penal colony was repealed.

In 1857 a survey of about 50 residents reported about 5000 acres (12.5 km²) of bushed land and a field of sugar cane on Kahoolawe. Tobacco , pineapples , pumpkins , piligrass (pee-lee) and bushes grew along the coast . In 1858 the Hawaiian government began leasing Kahoʻolawe to cattle breeding businesses. Some proved more successful than others, but the lack of fresh water remained a major problem. In the following 80 years the landscape changed dramatically - drought and uncontrolled overgrazing bared a large part of the island and a strong trade wind also blew away the topsoil .

From 1910 to 1918, the Hawaiian Territorial Government designated Kahoʻolawe as a forest reserve in the hope of restoring the fauna with a replanting program. The program failed and land leases became available again. In 1918, Wyoming-based skilled ranchers Angus MacPhee, with the help of Maui landowner Harry Baldwin , leased the island for 21 years to build a cattle ranch. In 1932 the cattle breeding business enjoyed moderate success. After occasional heavy rains, it looked like native grasses and flowering plants were sprouting, but the drought always returned after a short time. In 1941 MacPhee leased part of the island to the US Army . In the same year McPhee left the island with his cattle due to the persistent drought.

On December 8, 1941, after the attack of the Japanese on Pearl Harbor, the US army declared the martial law throughout Hawai'i and took control of Kahoolawe. The island was soon used to train or prepare Americans for the war in the Pacific . The use of kahoolawe as a training ground was seen as essential to the survival of many young Americans. The US was waging a new kind of war in the Pacific. Success depended in large part on precise, heavy artillery fire from ships that fired at enemy positions as Marines and soldiers scrambled to take control of the land. Thousands of soldiers, sailors, marines and airmen prepared on Kahoʻolawe for the brutal and costly attacks on islands such as the Gilbert Islands , the Marianas and Iwo Jima .

Training on Kahoʻolawe continued after World War II . During the Korean War , carrier-supported aircraft played an important role in attacking enemy airfields, convoys and troop assembly points. Dummies of airfields, vehicles, and other camps were set up on Kahoʻolawe, and while pilots underwent readiness inspections at nearby Barbers Point Naval Air Station , they practiced locating and hitting the dummies on Kahoʻolawe. Similar training was used in the Cold War and the Vietnam War , when dummies of aircraft and radar systems were set up for pilots.

In 1976, a group called "Protect Kahoʻolawe ʻOhana " (PKO) filed a lawsuit with the Federal Court of Justice to stop the Navy from using the island for military training. The aim of this group was to demand compliance with a number of new ecological laws and to secure the protection of the cultural riches of Kahoʻolawe. In 1977, the Hawai'i Federal District Court allowed the Navy to continue using the island for military purposes, but the court ordered the Navy to conduct an environmental impact assessment to ensure the continued existence of the historic sites. In 1980 the Navy and Protect Kahoʻolawe ʻOhana entered into a Consent Decree, which provided for the continuation of military training, surface cleaning on part of the island, soil protection, goat extermination and an archaeological survey.

On May 18, 1981, the entire island was placed on the National Register of Historic Places . During that time, Kahoʻolawe Archaeological District had 544 archaeological and historical sites and over 2000 individual features. As part of soil protection, workers laid lines of explosive charges to break the hard base layer and plant tree saplings. Used tires were brought to the island and placed in deep gullies to slow the erosion of the red earth from the barren highlands to the surrounding shores.

In 1990, President George HW Bush ordered that training on Kahoʻolawe be stopped. In 1991 the Kahoʻolawe Island Conveyance Commission was set up to recommend terms and conditions for the federal government to hand over Kahoʻolawes to the State of Hawaii.

Claims handover and dud cleanup

In 1993, Senator Daniel K. Inouye of Hawaii promoted Title X of the 1994 Fiscal Year Department of Defense Appropriations Act so that the US ceded Kahoʻolawe and the surrounding waters to Hawaii. Title X is also known as "Dud cleanup" and ecological restoration of the island in order to achieve "meaningful, safe use of the island for appropriate cultural, historical, archaeological and educational purposes as determined by the State of Hawaii" . The state then established the Kahoʻolawe Island Reserve Commission to exercise the policy and management of the Kahoʻolawe Conservation Area. As instructed by Title X, and in accordance with the required Navy / State of Hawaii Memorandum of Understanding, the Navy transferred the claim to the island to the State of Hawaii on May 9, 1994.

As required by Title X, the Navy maintained access control to the island until the disposal and ecological restoration were complete, or until November 11, 2003, whichever came first. The state agreed to develop a plan for the use of Kaho'olawe, and the Navy agreed to enforce a plan for cleanup in Congress based on the plan.

In July 1997 the Navy placed an order with the Parsons / UXB joint venture to dispose of the guns from the island. Following the state and public review of the Navy's cleanup plan, Parsons / UXB began operations in November 1998.

The Navy cleaned up the duds on the island, but many of them are still buried or on the surface. Others have been washed down the gullies, and still others are submerged offshore.

Kahoʻolawe Island Reserve

In 1993 the Hawaiian government established the Kahoʻolawe Island Reserve, which consists of the entire island and the surrounding ocean within a radius of 3 km. According to the law, the island and its waters may only be used for cultural, spiritual and existential purposes of the indigenous population as well as for fishing, ecological restoration, historical preservation and education. Commercial use is prohibited.

The government also set up the Kahoʻolawe Island Reserve Commission (KIRC) to administer the area. The restoration of the island needs a strategy to control erosion , restore vegetation and raise the water table . The plans include methods of insulating the gullies and reducing rainwater runoff. In some areas, introduced plants will be used to stabilize the soil before native plants can be planted.

Individual evidence

- ↑ z. B. Kahulaui . In: Meyers . 6th edition. Volume 010, pp. 429-430 .; Wilhelm Sievers, Willy Georg Kükenthal: Australien, Ozeanien und Polarländer (1902), p. 407 in the Google book search

- ^ Kahoʻolawe in the Geographic Names Information System of the United States Geological Survey

- ^ Kahoʻolawe in Hawaiian Dictionaries

- ^ National Park Service: Native Hawaiian Land Division

- ↑ Kepä Maly and Onaona Maly: HE MO'OLELO 'ÄINA NO KA'EO ME KÄHI' ÄINA EA'E MA HONUA'ULA O MAUI, A CULTURAL-HISTORICAL STUDY OF KA'EO AND OTHER LANDS IN HONUA'ULA, ISLAND OF MAUI, Makena, Hawai'i 2005, KPA No. MaKaeo110 (122705a) ( Memento of the original from June 17, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF file; 4.01 MB)

- ^ State of Hawaii: Department of Business, Economic Development and Tourism: The State of Hawaii Data Book 2003. A Statistical Abstract (PDF file; 3.89 MB), page 8

- ↑ PBR HAWA'I: PALAPALA HO'ONOHONOHO MOKU'AINA O KAHO'OLAWE, KAHO'OLAWE USE PLAN, prepared for KAHO'OLAWE ISLAND RESERVE COMMISSION, STATE OF HAWAI'I, 1995

- ^ Pauline N. King: A Local History Of Kahaoʻolawe Island: Tradition, Development, and World War. July 1993 (PDF; 4.8 MB)