Battle of Maxen

| date | November 20, 1759 |

|---|---|

| place | Maxen |

| output | Austrian victory |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

| 32,000 | 15,000 |

| losses | |

|

304 dead and 630 wounded |

approx. 2,000 dead and wounded and 11,741 prisoners |

Eastern theater of war

Pirna - Lobositz - Prague - Kolin - Groß-Jägersdorf - Moys - Roßbach - Breslau - Leuthen - Domstadtl - Olmütz - Zorndorf - Hochkirch - Kay - Kunersdorf - Hoyerswerda - Maxen - Koßdorf - Landeshut - Liegnitz - Oschatz - Berlin - Wittenberg - Torgau - Döbeln - Burkersdorf - Reichenbach - Freiberg

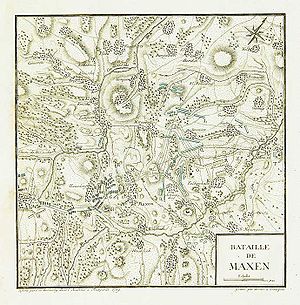

The Battle of Maxen - also known as Finckenfang von Maxen - on November 20, 1759 was a battle between Austrian and Prussian troops during the Seven Years War ( 1756 - 1763 ), which resulted in the complete defeat of the 15,000 Prussians under Lieutenant General Friedrich August von Finck against the 32,000 Austrians under Leopold Joseph Graf Daun ended.

initial situation

After the battle of Kunersdorf lost for Prussia and the termination of the Austro-Russian offensive near the Oder, Frederick the Great again took a more offensive approach with the remnants of his army that had been gathered in Kunersdorf. In order to stabilize the situation in Saxony, the bulk of these troops moved there and subsequently retook Leipzig , Torgau and Wittenberg . Meanwhile, Dresden was lost to Prussia through the capitulation of the Prussian garrison under General Schmettau . At this time, Prussian troop contingents under Prince Heinrich of Prussia , Lieutenant General Finck and Major General Wunsch united against the Austrians who were victorious before Dresden. In addition to these troops, the two main armies - the Prussian and the Austrian - moved into Saxony. The attempt of the main army of the Austrians under Daun to isolate the smaller of the two Prussian armies failed. It was not until the beginning of November 1759 that 60,000 Prussians in the main army under their king were concentrated in the Electorate of Saxony, while the Austrians concentrated exclusively around Dresden. To secure his own lines of communication and to threaten the Austrian supply lines, Frederick the Great now thought of distributing his troops widely. A cavalry force was also sent to Bohemia under the command of Colonel Friedrich Wilhelm von Kleist , which for example destroyed the Aussig warehouse there. At the behest of Frederick the Great on November 15, 1759, the corps of Lieutenant General Friedrich August von Finck in the rear of the main Austrian armed forces was to threaten above all the connecting road through the Ore Mountains and the Elbe Sandstone Mountains from Bohemia. The von Finck corps with a total of 18 battalions of infantry and 25 squadrons of cavalry arrived on the plateau of Maxen on November 18, 1759, after the advance guard had occupied Maxen a day earlier. These troops included a total of seven infantry battalions, which had already suffered badly in the war year 1759 and were far below their target number.

Formation of the Prussian corps

The Prussians moved into a camp on the plateau, which was separated from the main army of Frederick the Great by an extensive forest. Incidentally, the river Müglitz was behind the Prussian troops . The camp of the Austrian main army began not far from the Prussians in the so-called Plauen reason .

The Austrians march

The Austrians planned to attack the Prussians from all directions simultaneously. For this purpose the Austrians marched on November 19, 1759. An attack column attacked under the command of Lieutenant General of the Imperial Army Prince Stolberg-Gedern with 4,500 German-Austrian infantrymen, Croatian light infantry (allegedly through the Croatian Gorge from the Lockwitztal west of Maxen) and two Austrian hussar regiments east of Maxen. Among other things, this column was supposed to prevent the Prussians from escaping through the Müglitztal . 6,000 Austrians under General von Brentano (1718–1764) attacked from the north . Advancing through ice and snow, 17,000 Austrians attacked from the southwest from Dippoldiswalde , while 3,500 soldiers came to attack from the northeast from Dohna . During the approach, Austrian troops clashed with a Prussian supply convoy near Dippoldiswalde, and the Prussians just managed to save the supply convoy and its accompanying troops by deploying two cavalry regiments.

Course of the battle

The Austrians attacked the Prussians with four attack columns with a total of 32,000 soldiers from the Austrians and the Imperial troops at the same time. First, the artillery opened fire at 2 p.m., followed by an infantry attack from 3:30 p.m. The main attack from the south was divided into four smaller attack columns of infantry, flanked by the cavalry, and aimed at the center of the Prussians. The Prussian troops first had to let themselves fall behind the heights of Hausdorf until the heights were taken under fire by the Austrian artillery. The heights upstream from Maxen were doggedly defended by three Prussian grenadier battalions, among others, while the soldiers of the infantry regiments (No. 47) Grabow and (No. 38) Zastrow - mostly squeezed Saxon soldiers - fled and the Austrians attacking the contour line thereby defeated the Prussians could push back. A cavalry counterattack by Dragoon Regiment No. 12 Eugen v. Württemberg collapsed. During the subsequent assault by the Austrians on Maxen itself, it was set on fire by the Austrian artillery. Maxen temporarily fell into Austrian hands. The Grenadier Battalion Willemy (No. 4/16 ), however, recaptured Maxen, while the 2nd Battalion of the Infantry Regiment (No. 11) Rebentisch - almost predominantly recruited from prisoners of war - simply disbanded. The grenadier battalions Willemy and Beneckendorff as well as the infantry regiment (No. 12) Finck were able to hold Maxen as rearguard until it was dark. The catchment position formed in the dark was overrun by further attacks by the Austrians. In some cases, individual attacks by Prussian troops could still be repulsed during the night, but after the end of the fighting only 2,825 Prussian soldiers of the original eleven infantry battalions concentrated around Maxen were still operational. At least half of the Prussian infantry deserted during the battle. Only the seven battalions under General Wunsch at Dohna were still in rank and file. An attempt to break out of the main army or a resumption of fighting seemed futile. A retreat through the Müglitztal was nipped in the bud by the vigilance of the Austrians. The Prussian cavalry, which had almost not intervened in the battle, still tried to sneak out of the enclosure, but this escape attempt by the 1,900 soldiers only came a few kilometers under the poor ground conditions until Finck finally surrendered.

In addition to the 11,000 to 12,000 unwounded Prussian prisoners, the Austrians fell into their hands with 70 cannons, 96 flags and 24 standards. An exchange of prisoners hoped for - especially by General Finck - did not take place until the end of the war, so these soldiers had to be written off for the further course of the war.

After the war Finck was sentenced to two years imprisonment by a Prussian military court. The following generals were also arrested and charged: Johann Jakob von Wunsch (acquittal), Leopold Johann von Platen , Johann Karl von Rebentisch , Otto Ernst von Gersdorf , Jakob Friedrich von Bredow , Heinrich Rudolph von Vasold , Daniel Georg von Lindstedt , Friedrich Wilhelm of the Moselle .

The Gersdorff hussar regiment was disbanded due to failure. In retrospect, all of Maxen's Prussian troops were viewed poorly by Frederick the Great.

Prussian troops captured

As far as is known, the troops captured at Maxen were given the names of the old Prussian army. The name of the respective chief of the regiment or the commander of the battalion is written in italics. The grenadier battalions were named after their commanders; in addition, it was sometimes specified from which regiments the grenadier companies were drawn to form the battalion. If one of the regiments was a so-called fusilier regiment, this is also noted.

- infantry

- Grenadier Battalion 4/16 Willemy (formed from the grenadier companies of infantry regiments No. 4 and No. 16)

- Grenadier Battalion 13/26 Finck

- Grenadier Battalion 19/25 Schwerin

- Grenadier Battalion 37/40 Manteuffel

- Grenadier Battalion 41/44 Beneckendorff

- Standing Grenadier Battalion 3 Beneckendorff

- a battalion of the infantry regiment (No. 9) Schenkendorf

- both battalions of the infantry regiment (No. 11) Rebentisch

- a battalion of the infantry regiment (No. 12) Finck

- a battalion of the infantry regiment (No. 14) Lehwaldt

- a battalion of the infantry regiment (No. 21) pods

- a battalion of the Infantry Regiment (No. 29) Knobloch

- a battalion of the infantry regiment (No. 36 Fusilier) Alt-Münchow

- 1st Battalion Infantry Regiment (No. 38 Fusilier) Zastrow

- a battalion of the infantry regiment (No. 45 Fusilier) Hessen-Cassel

- Remnants of the infantry regiment (No. 47 Fusilier) Grabow

- 2nd Battalion of the Infantry Regiment (No. 48 Fusilier) Sallmuth

- Remnants of the infantry regiment (No. 55 Fusilier, former Saxon regiment Lubomisky) Hauss

- Free Battalion No. 3 Salenmon

- cavalry

- Cuirassier Regiment (No. 6) Vasold

- Cuirassier Regiment (No. 7) Horn

- Cuirassier Regiment (No. 9) Bredow

- Dragoon Regiment (No. 11) Jung-Platen

- Dragoon Regiment (No. 12) Eugen v. Württemberg

- Hussar regiment (No. 6 also Brown Hussars) Werner

- Hussar Regiment (No. 7) Gersdorff

Meaning of Maxen

Without much impact on the further course of the war, Maxen's fincken trapping led to an improvement in the reputation of Field Marshal Leopold Joseph Graf Daun . Both main armies now wintered in the Dresden area. What made the battle of Maxen outstanding was that half of the Prussian infantry deserted during the fight. Part of the blame for the poor performance was primarily the poor morale of the Prussian troops. The Battle of Landeshut a few months later, with a similar outcome, was nowhere near as catastrophic as the Prussians fought until all ammunition was used up and the cavalry successfully fought their way out of their grip. . The Prussian King Frederick II forgave Finck's surrender not: ... it is a very egregious example that a Prussian corps niederleget the gun from the enemy ... . Even a year later wrote Frederick the Great in a letter that if we lose, we must predate our downfall on the day of the shameful adventure of Maxen ... .

Significance compared to the battle of Gabel

Maxen was not the first time in the Seven Years' War in which the troops of Austria could force entire Prussian troops to surrender. For example, on July 15, 1757, at Gabel , four battalions were surrounded and captured.

Defeat of the Diericke detachment

Only thirteen days after the Maxen battle, which was so devastating for Prussia, on December 3, 1759, Major General Diericke and three battalions of Prussian infantry near Meißen got into a battle with his superior Austrian troops, the three Prussian battalions were smashed and Diericke and 1,500 soldiers were taken prisoner got.

Significance for the western theater of war

The loss of the cavalry regiments was so devastating that Frederick the Great was forced to recall a large part of the Prussian cavalry from the West German theater of war (at least ten squadrons of dragoons) to compensate for the lost cavalry. The withdrawn soldiers could only be partially replaced.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Duffy, Frederick the Great and His Army, p. 292.

- ↑ Christopher Duffy, Frederick the Great - The Biography, p. 276 f.

- ^ Duffy, Frederick the Great, p. 278.

- ↑ The Lockwitzgrund is more likely due to the distance.

- ↑ a b c Joachim Engelmann, The battles of Frederick the Great, p. 128.

- ↑ a b Duffy, Friedrich der Große, p. 279.

- ^ Duffy. Frederick the Great and his Army, p. 292.

- ↑ Duffy, Friedrich the Great, pp. 279–281.

- ^ Duffy, Frederick the Great, p. 280.

- ^ Olaf Groehler, The Wars of Frederick II. S, 131.

- ↑ a b c Duffy, Friedrich the Great, p. 281.

- ↑ Duffy, Army, p. 347 ff.

- ^ Duffy, Frederick the Great and His Army, p. 359.

- ↑ Christopher Duffy, Frederick the Great, p. 282.

Web links

literature

- Christopher Duffy : Frederick the Great. The biography. Albatros Verlag, Düsseldorf 2001, ISBN 3-491-96026-6 .

- Christopher Duffy: Frederick the Great and his Army. Motorbuch Verlag, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-613-03050-3 .

- Joachim Engelmann: The battles of Frederick the Great. Nebel-Verlag, Utting 2001, ISBN 3-89555-004-3 .

- Olaf Groehler : The wars of Frederick II. 6th edition. Brandenburgisches Verlagshaus, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-327-00038-7 .

- Marcus von Salisch: Two "unheard of examples". The capitulations of Pirna in 1756 and Maxen in 1759 in comparison , in: Neues Archiv für Sächsische Geschichte 84 (2013), pp. 97–132.

- Michael Simon / Gisela Niggemann-Simon: About the power of images or 'Greetings from Finckenfang' , in: Andreas Hartmann [u. a.] (ed.): The power of things. Symbolic communication and cultural action. Festschrift for Ruth.-E. Mohrmann (Contributions to Folk Culture in Northwest Germany 116), Münster 2011, pp. 417–427.

From the series "All about Finckenfang", Verlag Niggemann & Simon, 01809 Maxen:

- Issue 1: Werner Netzschwitz: The Battle of Maxen on November 20, 1759. Maxen 2004, ISBN 3-9808477-0-5 .

- Issue 9: Michael Simon: War and Peace in Maxen. Maxen 2005, ISBN 3-9808477-9-9 .

- Booklet 13: Michael Simon: "It has been a very unheard-of example to date ..." The finckenfang at Maxen in November 1759. Maxen 2009, ISBN 978-3-9810717-3-3 .