Rice runner

Reisläufer (derived from Reisige ) were late medieval Swiss mercenaries who were in the service of numerous European rulers until the 17th century. The Middle High German travel means "military exodus, war campaign, campaign" and is the forerunner of the New High German word travel . The Reisläufer hired himself out on his own in foreign service - in contrast to the capitulated service , which was based on a military surrender , that is, a delivery contract for soldiers between two countries.

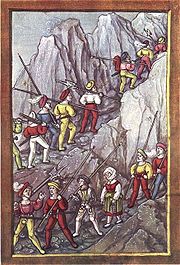

Reisläufer after a representation by Urs Graf

|

history

etymology

In the Middle Ages armed servants or mounted escorts were called travelers , derived from travel or journey in the sense of "war trip ". Wags were therefore those who had to undertake campaigns at the behest of their master. In the 16th century, this term was used to refer to (armed) riders - in contrast to the rice walkers , who belonged to the infantry, that is to say: the fighters of the infantry .

Beginnings

The central Swiss mercenaries and soldiers ( Uri , Schwyz , Unterwalden ) were feared and sought after in the European theaters of war even before the founding of the Old Confederation . The Ennetbirgischen campaigns from 1402, during which Milanese valleys were conquered, marked the beginning of the Swiss expansion efforts. Between 1400 and 1848 many Swiss earned their living as mercenaries in foreign armies, most of them fleeing poverty in their home country.

For their war aid at Faenza they received the freedom letter from Friedrich II . Their fighting spirit against a devastating superiority in the battle of St. Jakob an der Birs led to a treaty with France in 1444, with the possibility of recruiting federal mercenaries.

Reisläufer have been recruited on a large scale since the Swiss military successes in the Burgundian Wars (1474–1477). Even before that, during the conflicts with Habsburg , especially due to the battles of Morgarten and Sempach , the reputation of the federal troops was "invincible". The military penetration of the federal Reisläufer was based on the new infantry tactics of the " heap of violence ", which was superior to the contemporary knight armies. The main weapons of the Reisläufer were pikes and halberds , for close combat Swiss swords and daggers.

The number of Swiss travelers a warlord had determined his chances of victory. This was particularly true in the Italian Wars from 1494, which were triggered by the invasion of France in the struggle for the succession to the throne in Naples and which expanded into the struggle between the Holy Roman Empire , France, Spain and the Pope for supremacy in Italy .

Reisläufer were not under the jurisdiction of the warlord , but that of their own captains, and thus their own judges and their own law. Overpopulation, especially in the original cantons, a thirst for adventure, booty and pay were important reasons to obey the commands of the authorities or to move out on your own.

Paying pensions to official representatives of the cantons or influential personalities such as Cardinal Matthäus Schiner has become the most important means of recruiting . Not infrequently, the future opponents of the war outbid each other to the advantage of the federal politicians, which, at least since the battle of Marignano , gave them a reputation for corruption at the expense of the people. Cases in which the Swiss fought against the Swiss increased. Jakob Meyer zum Hasen , Mayor of the City of Basel from 1516 to 1521 , was relieved of his office along with his fellow councilors in the "Pensions Storm" in 1521. The pension system as the economic side of the Reislauf was one of the most important driving forces of the Zwingli Reformation .

Transition to standing Swiss regiments

France was the first country in 1497 with the Guard troops of hundreds of Swiss set up a long-established Swiss unit. In the 15th and 16th centuries, most mercenary troops were employed only for the period of conflict.

As a result of the Battle of Marignano , Switzerland concluded in the November 29, 1516 Freiburg im Uechtland the Eternal Peace with France. In the surrender treaty, which was renewed several times until 1792 and which served as a model for treaties with other European powers, the Helvetic Corps (name of the Confederation in the 17th century) undertook to provide contingents for France that could be raised in Switzerland. The contract stated that:

- the Swiss were only allowed to serve in Swiss regiments, under the Swiss flag and under Swiss officers, and the highest Swiss commander (Colonel General) could only be directly subordinate to the king or a member of the royal family.

- the Swiss soldiers could only be sentenced by Swiss judges, according to Swiss law and under federal sovereignty.

- the Diet had the right to recall the Swiss regiments for defense at any time if the Confederation was threatened.

In addition to the official service based on surrender, the wild pay service also increased in the 17th century. While the cantons and Graubünden capitulated with Spain , Savoy , Venice and Genoa , hundreds of Swiss people went into unregulated military service, mainly to Sweden , Saxony and Bavaria .

Louis XIV finally went over to putting eleven Swiss line regiments into permanent service in France from 1671, which dragged on until 1758, when the last two (they had turned twelve after all) were taken into service (Régiment de Lochmann and Régiment d 'Eptingen) → Infantry étrangère de ligne . In addition there were other unregulated free companies. Other countries copied this institution, such as Spain (surrender with Catholic cantons), the Netherlands (surrender with the Reformed cantons), Venice (until 1719), England , Poland , Austria (until 1740) and Sardinia-Piedmont . In most of the wars in Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries, Swiss troops fought.

End of traveling

The intensification of the drill, the restriction of looting and the devaluation of money made the pay service appear less and less attractive for young men. At the end of the 18th century it became increasingly difficult for salaried entrepreneurs and regiment owners to fill the regiments' stocks. The soldiers became more and more aware of the risks given the high casualties of Swiss units. After the beginning of the French Revolution, France dismissed the Swiss regiments, which were unpopular with the people, following the Tuileries storm on August 20, 1792 in violation of all existing treaties. Numerous mercenaries then hired themselves in regular French units or sought service in other European countries.

Until the French troops marched into Switzerland in 1798, there were no regular Swiss troops in France. The Helvetic Republic undertook to provide France with troops again, but could only fill the stocks with compulsion and great effort. During the Napoleonic Wars , tens of thousands of Swiss mercenaries served in France, Spain, Great Britain and Austria. Especially in Spain and on the Russian campaign in 1812 there were high losses among Swiss units. In Spain, a total of around 30,000 Swiss served on both sides.

After the end of the Napoleonic wars, the cantons concluded new military capitulations with France, the Netherlands, Prussia , the Holy See and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies .

In 1814, the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm III. , who was the prince of the canton of Neuchâtel , which joined the Swiss Confederation in 1814 , formed the Prussian Guard Rifle Battalion in coordination with the canton's State Council . It should include Neuchâtel and other Swiss volunteers. The State Council of Neuchâtel had the right to designate officers. However, until 1848 only a few Swiss were willing to enter Prussian service, which is why the battalion soon consisted predominantly of Prussian volunteers.

France and the Netherlands ended the practice of employing foreign regiments in 1830 and 1829, respectively. In France, a large number of the men serving in the Swiss regiments at that time transferred to the newly founded Foreign Legion , so that at the beginning it was heavily influenced by Swiss mercenaries. In Italy, the Swiss regiments fought for the Pope or for the King of the Two Sicilies against the liberal and nationalist insurgents in 1821, 1830 and 1848. As a result, military service became increasingly unpopular with liberal Swiss politicians. The canton's constitutions therefore prohibited military capitulations from being concluded in 1830.

By federal decree of June 20, 1849, the newly founded, liberal Swiss federal state prohibited the conclusion of military surrenders (Art. 11 BV) at the federal level. Members of the federal authorities were also not allowed to accept other pensions, titles or medals (Art. 12 BV). However, the cantons refused to cancel the existing military surrenders, so that the ban only applied to the conclusion of new contracts. Federal legislation also prohibited the wild recruiting of Swiss people outside of the existing military capitulations, but still without penal provisions (Federal Law 1/432, June 20, 1849). In 1851 the recruiting of Swiss national service was banned, in 1853 it was banned from all Swiss residents.

Nevertheless, Great Britain recruited 3,338 soldiers in Switzerland for the Crimean War in 1855 , but without completing a military surrender. But before the British Swiss Legion (BSL) could take action against the Russian troops , hostilities ceased. During the Lombard-Austrian War of 1859, after Perugia was sacked by papal troops, including Swiss mercenaries, there were strong anti-Swiss reactions in Italy .

After a mutiny among the Swiss mercenaries in the service of the Kingdom of Naples , the Federal Council forbade the active recruitment of mercenaries and the entry of Swiss citizens into foreign services by a federal law of 30 July 1859 (BG 6/312), so that the treaties with Naples, which expired on July 15, 1859, could no longer be renewed. This meant the end of military entrepreneurship in Switzerland, around 7,500 mercenaries returned to Switzerland from Naples , and hundreds joined other armies.

However, beyond 1859, thousands of Swiss mercenaries served in the Foreign Legion. Numerous officers took on commands in foreign armies, such as the former Federal Councilor Ulrich Ochsenbein , because the federal law permitted service in the regular national troops abroad as long as compulsory service in Switzerland was not violated. Service in Swiss regiments was also still possible with Federal Council approval. This enabled the Swiss troops to remain in the service of the Holy See. In addition to the Swiss Guard , the Pope recruited two regiments for his army in the 19th century through a surrender with the cantons. One of these regiments remained in service until 1870 when the Papal State was conquered by Italy.

situation

Although recruiting was forbidden, joining foreign military services remained unpunished for individual Swiss citizens. Only with the entry into force of the Military Criminal Code (MStG) of 1929, which banned it in Art. 94, did this behavior become punishable.

Nevertheless, numerous Swiss fought for the Spanish republic in the Spanish Civil War . Swiss also served in the German Waffen SS . After their return they were prosecuted in Switzerland. Service in the French Foreign Legion is still a criminal offense. It is disputed whether private military companies that offer their services in Iraq and elsewhere fall under the definition of Art. 94 MStG.

The only exception is the Pontifical Swiss Guard , where Swiss people still serve. Here, however, the deployment is viewed as (house) police duty, which means that the guardsmen do not fall under the mercenary ban. Prior service and training in the Swiss Army , as well as Catholic faith and impeccable behavior are required for entry .

Tactics and warfare

The horrors of the early modern battlefield from the perspective of the traveler and artist Urs Graf , 1521

1515: Battle of Marignano

Urs Graf : Council of war on the piano procession

Hans Asper : The Zurich mercenary leader Wilhelm Frölich in 1549

The rice walkers' tactic was to attack the opposing troops with heap of violence before they were properly deployed. A gang of violence or cadre was a fighting formation up to 50 members deep. In front stood the pikemen with their five meter long spears , behind them came the halberd-bearers and swordsmen with long two-handed hands . The first and often also the last link were armored double mercenaries , these wore an iron helmet ( morion ) and were armed with arquebuses . When the pikes and halberds could no longer be used in the crowd, one fought with short swords, the katzbalgern .

Often the rice walkers faced German mercenaries , with whom bloody battles for the favor of the gold of the princes and warlords had repeatedly broken out. The Landsknechte themselves based their line-up on the Swiss mercenary armies and later continued to develop them. In the beginning, Landsknechte were considered the worse Swiss and received lower pay and less booty. Due to various political events and military defeats of the Reisläufer, however, their reputation and their availability dwindled, whereby the German mercenaries in the following wars in Europe became the dominant mercenary troops.

Countries with official Swiss troops

"Official" Swiss troops were those units whose recruitment had been explicitly permitted by the participating cantons in a military surrender. These units were not part of the normal armed forces of the recruiting countries and received a contractually agreed pay, but swore allegiance to the monarch who provided the money.

List of countries with Swiss guards

- Kingdom of France : Cent-suisses , Swiss Guard 1616–1792, 1815–1830; about 2,400 men

- Austria : Hundred Swiss in the Hofburg

- Sardinia-Piedmont : Hundertschweizer, Swiss Guard, 1579–1831; between 175 and 112 men

- Republic of the Seven United Provinces : Life guards “Guardes Zwitzers” 1672 – not specified , up to 100 men; Swiss Guard 1748–1796, approx. 1,600 men

- Kingdom of Naples : Swiss Guard Regiment 1734–1798; approx. 1,660 men

- Papal states : Papal Swiss Guard since 1506

Countries with Swiss troops in the 18th century

At the time of the Peace of Aachen in 1748, the following countries had Swiss troops:

- France:

- 12 regiments of the line,

- Regiment of the Gardes suisses,

- Hundred Swiss,

- Compagnie des Suisses de Monsieur le comte d'Artois

- Compagnie des Gardes suisses de Monsieur le Comte de Provence

- some free companies; 23,055 men

- Austria: 1 regiment, Hundertschweizer; 2,400 men

- Republic of the Seven United Provinces (1693–1795): 9 regiments; 20,400 men

- Savoy-Sardinia: 5 regiments, 1 battalion, 100 Swiss; 10,600 men

- Spain: 6 regiments; 13,600 men

- Naples (from 1734): 3 regiments, 1 battalion; 6,700 men

- Papal States: Papal Guard; 133

A total of 36 regiments with 76,988 men served in regular Swiss troops in foreign services in 1748.

Countries with Swiss troops at the time of the Napoleonic Wars

- France 1798–1803: 33 battalions of infantry, 3 squadrons of cavalry, 1 battery; 18,000 men

- France 1803–1814: 4 regiments; 16,000 men, from 1812 12,000 men (including troops from Neuchâtel and Valais)

- Great Britain 1795–1816: 2 regiments (de Meuron in Ceylon, 1813 in Canada; von Roll): approx. 3,100 men

- Great Britain 1799–1801 / 1816: Swiss émigré army or Legion Rovéréa (4 regiments, 2 battalions), from 1801 Regiment Wattenwyl: numbers fluctuating strongly

- Spain until 1820/35: 6 regiments; 12,000 men ( Suizos azurros according to their light blue uniforms)

- Papal States: Papal Guard; 133

- Sardinia-Piedmont: until 1815, 100 Swiss until 1832

Countries with Swiss troops 1814–1859

- France 1814–1830: 4 regiments of the line, 2 regiments of guards, 100 Swiss; 14,100 men

- Prussia 1814–1848: Guard Rifle Battalion ; 429 men

- United Kingdom of the Netherlands 1814–1829: 4 regiments; 10,000 men

- Naples 1829–1855 / 59/61: 4 regiments; approx. 8,000 men

- Papal States: 2 regiments (until 1870), Papal Guard (until today); 350 men

- Great Britain (1855): British Swiss Legion; 3,300 men

See also

- Soldier trade

- List of Swiss line regiments in French service

- Rice Keten-Schützengesellschaft

- Swiss troops in foreign service

literature

- Jost Auf der Maur: mercenaries for Europe. More than a Schwyz family story. Realtime Verlag, Basel 2011, ISBN 978-3-905800-52-4 .

- Alain-Jacques Czouz-Tornare: Rice Runner . In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- Henri Ganter: Histoire du Service Militaire des Régiments Suisses à la Solde de 'Angleterre, de Naples et de Rome. Ch. Eggimann & Cie., Geneva 1906, OCLC 715068556 (French).

- Valentin Groebener (di: Valentin Groebner ): Dangerous gifts. Ritual, politics and the language of corruption in the Confederation in the late Middle Ages and at the beginning of the modern era (= conflicts and culture. Historical perspectives. Volume 3 (d. I. 4)). UVK - Universitäts-Verlag, Konstanz 2000, ISBN 3-87940-741-X (habilitation thesis Uni Basel 1997).

- Philippe Henry: Foreign services. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- Werner Meyer : Federal Sold Service and Economic Conditions in the Swiss Alpine Region around 1500. In: Stefan Kroll , Kersten Krüger (Ed.): Military and rural society in the early modern era (= rule and social systems in the early modern era, volume 1). Lit, Münster u. a. 2000, ISBN 3-8258-4758-6 , pp. 23-39.

- Christian Padrutt: State and War in the Old Confederation. Studies on the relationship between authorities and warriors in the three leagues, primarily in the 15th and 16th centuries (= spirit and work of the times. Issue 11, ISSN 0435-1673 ). Fretz and Wasmuth, Zurich 1965 (also dissertation University of Zurich, Philosophical Faculty I); New edition by the Verein für Bündner Kulturforschung, Bündner monthly sheets, Chur 1991, ISBN 3-905241-20-X .

- Johann Jakob Romang : The English Swiss Legion and their stay in the Orient. F. Wyß, Langnau 1857, OCLC 602320820 .

- Walter Schaufelberger : The old Swiss and his war. Studies on warfare mainly in the 15th century (= economy, society, state. Volume 7, DNB 364567546 ). Europe, Zurich 1952 (also dissertation University of Zurich); 3rd edition, Huber, Frauenfeld 1987, ISBN 3-7193-0980-0 .

Web links

- Jonas Briner: Child soldiers in the Confederation , with detailed. Lit.-catalog (PDF file; 321 kB)

- History of the British Swiss Legion

- The Swiss - Reisläufer from the Alps on kriegsreisen.de

- Swiss battles - In Italy, Swiss travelers and mercenaries met on kriegsreisen.de

- Swiss regiments in French service in the archive database of the Swiss Federal Archives

- Swiss regiments in the service of the Vatican in the archive database of the Swiss Federal Archives

- Swiss regiments in Dutch service in the archive database of the Swiss Federal Archives

- Swiss regiments in British service in the archive database of the Swiss Federal Archives

- Swiss regiments in Neapolitan service in the archive database of the Swiss Federal Archives

Remarks

- ↑ See Schweizerisches Idiotikon , Volume VI, Column 1288 ff., Article Reis ( digitized version )

- ^ Population> Swiss Abroad> Former Emigrants , In: swissworld.org, publisher: Presence Switzerland , General Secretariat of the Federal Department of Foreign Affairs . Accessed February 13, 2012.

- ^ Albert A. Stahel : From the foreign services to the militia army. In: Albert A. Stahel (Ed.): Army 95 - Opportunity for the militia army? (= Strategic Studies. Vol. 7). Verlag der Fachvereine, Zurich 1994, ISBN 3-7281-2094-4 , p. 11 f.

- ↑ De Vallière, pp. 464-737.

- ↑ http://xoomer.virgilio.it/bandsabaude/Bandieres1.html

- ↑ Archived copy ( Memento of the original from March 8, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ see especially: Pensions in Basel, September 1501 to October 1521 and for Zwingli's fight against Reislauf and pensions: Postscript 1: The Reformation of Dangerous Gifts and the Bodies of Women .