Freiburg in Üechtland

| Freiburg Friborg |

|

|---|---|

| State : |

|

| Canton : |

|

| District : | Saane |

| BFS no. : | 2196 |

| Postal code : | 1700-1709 |

| UN / LOCODE : | CH FRB |

| Coordinates : | 578929 / 183935 |

| Height : |

587 m above sea level M. |

| Height range : | 531–704 m above sea level M. |

| Area : | 9.28 km² |

| Resident: | 38,197 (December 31, 2019) |

| Population density : | 4116 inhabitants per km² |

|

Proportion of foreigners : (residents without Swiss citizenship ) |

36.7% (December 31, 2019) |

| Mayor : | Thierry Steiert ( SP ) |

| Website: | www.ville-fribourg.ch |

|

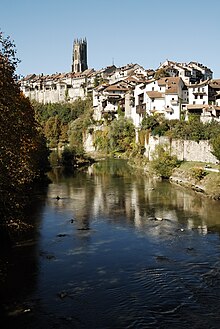

View of the city |

|

| Location of the municipality | |

Freiburg ( French Friborg [ fʀibuːʀ ], Italian Friburgo, Friborgo , Swiss German Fryburg [ fribʊrg ], in the regional Senslerdeutsch [ friːbʊrg ] or [ friːbərg ], Franco- ) is the capital of the eponymous canton and the Saane district . To distinguish it from the German Freiburg im Breisgau , the addition in Üechtland (short i. Ü. Or i. Üe .; pronounced [ ˈyəçtland ]) or (Switzerland) can be used. With a current population of almost 40,000, Friborg is the fourth largest city in French-speaking Switzerland after Neuchâtel .

Friborg, located on both sides of the Saane in the Swiss Plateau , is an important economic, administrative and educational center with a bilingual university on the cultural border between German and French-speaking Switzerland. The well-preserved old town lies on a narrow rock spur above the Saane valley and in its narrow alluvial plain .

geography

The old town of Freiburg is 581 m above sea level. M. , 28 km southwest of Bern (linear distance). The city extends on the plateau on both sides of the Saane ( Sarine in French ), the riverbed of which is cut deep into the molasses sandstone layers , in the Swiss plateau . The old town is located on a meander spur just over 100 meters wide west of the Saane, around 40 m above the valley floor of the river. Most of the city quarters are located on the high plateau at an average of 620 m above sea level. M. and on the adjacent hills, while the valley floor of the Saane is only inhabited in the area of the old town meander, the formerly poor lower town. The lowest point in the city is 525 m above sea level. M. in the Windig area.

The area of the municipality, which is relatively limited to 9.3 square kilometers for a city, comprises a section of the Molasse plateau in the Freiburg Central Plateau. From south to north, the area is crossed by the winding course of the Saane, which has cut into the plateau up to 100 meters deep due to erosion . The valley floor is generally 200 to a maximum of 500 meters wide. South of the city is Lake Pérolles, dammed in 1872, with the oldest gravity dam in Europe. The damming up of the Schiffenensee begins around one kilometer north of the old town . At the reservoirs, the Saane takes up almost the entire available width of the valley floor.

On both sides, the flat valley floor is flanked by steep slopes that are largely wooded and partly run through with sandstone . This is followed by the high plateau of Freiburg (610 to 630 m ) in the west , which in turn is bounded by the Molasse hills of Chamblioux ( 681 m ) and Le Guintzet ( 690 m ). To the east of the Saane, the community soil extends to the heights of Schönberg ( Schœnberg in French ), which is 702 m above sea level. M. represents the highest point of the urban area, and Bürglen (French Bourguillon; up to 700 m ). In between there is the Galtera (French: Gottéron ) trench, which is also sunk into the plateau and flows into the Saane in the area of the meander of the old town. In 1997, 61% of the municipal area was in settlements, 18% in forests and woodlands, 14% in agriculture and a little less than 7% was unproductive land.

The political municipality of Freiburg includes the former hamlet of Bürglen ( 655 m ) on the plateau south of the Galterngraben and part of the Schönberg district (up to 700 m ) on the eastern city limits north of the Galterngraben; the greater part is already in the municipality of Tafers. Neighboring communities of Freiburg are Düdingen and Tafers in the east, St. Ursen and Pierrafortscha in the southeast, Marly in the south, Villars-sur-Glâne and Givisiez in the west and Granges-Paccot in the north .

City quarters

| Quartier German | French | BFS code | Residents at the end of 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Castle | Bourg | 2196011 | 2,400 |

| Beauregard | 2196012 | 7,527 | |

| law | law | 2196013 | 6'220 |

| Pérolles | 2196014 | 6,023 | |

| Neustadt | Neuveville | 2196015 | 1,553 |

| Au | eye | 2196016 | 1,088 |

| Schoenberg | Schoenberg | 2196017 | 9,485 |

| Places | 2196018 | 3,144 | |

| Bürglen | Bourguillon | 2196019 | 691 |

climate

| Freiburg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate diagram | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Average monthly temperatures and precipitation for Freiburg

Source: www.meteoschweiz.admin.ch

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

population

resident

With 38,197 inhabitants (permanent resident population on December 31, 2019), Friborg is the largest city in the canton of Friborg. Around 29% of them are foreigners. Especially at the beginning of the 20th century and from 1930 to 1970 the population of Freiburg increased significantly. The peak was reached in 1974 with around 42,000 inhabitants. After that, a population decline of around 14% was recorded, but this has been stopped. Today, the agglomeration of Friborg has one of the youngest populations in Switzerland due to the influx of families from the expensive residential communities on Lake Geneva .

The Federal Statistical Office (FSO) puts the agglomeration at around 100,000 inhabitants (2008). The greater / economic area of Freiburg has a population of around 75,000 (2015). In addition to the city of Freiburg, this includes the municipalities of Avry , Belfaux , Corminboeuf , Givisiez, Granges-Paccot, Marly, Matran and Villars-sur-Glâne.

The settlement areas of the municipalities of Freiburg, Villars-sur-Glâne, Givisiez and Granges-Paccot have largely grown together. Directly on the eastern edge of the city are the district of Klein-Schönberg (French: Petit-Schoenberg) belonging to Tafers and the hamlet of Uebewil (French: Villars-les-Joncs) belonging to Düdingen. This closed settlement area has around 60,000 inhabitants (2015). New residential areas have emerged since the 1950s, especially in the west of the city (Beaumont, Jura, Torry) and in the Bellevue and Schönberg districts east of the Saanegraben. Partly extensive apartment block quarters, partly also single-family house quarters like around the hills of Chamblioux and Le Guintzet as well as on the upper Schönberg were created.

| City of Freiburg - population development | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| year | 1450 | 1798 | 1850 | 1870 | 1888 | 1900 | 1910 | 1930 | 1950 | 1960 | 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2010 | 2016 |

| resident | 6,000 | 5'117 | 9,065 | 10,581 | 12'195 | 15,794 | 20,293 | 21,557 | 29'005 | 32,583 | 39,695 | 37,400 | 36,355 | 34,897 | 35,547 | 38,829 |

| Proportion German-speaking (from 1888) | 37.1% | 35.4% | 33.0% | 33.3% | 33.2% | 28.0% | 22.8% | 21.2% | ||||||||

languages

Of the residents in 2016, 68.6% (63.3%) spoke French and 27.4% (21.2%) German . 21% also speak a foreign first language , including Albanian, English, Serbo-Croatian and, above all, Portuguese (the figures refer to the permanent resident population in the canton of Friborg and for the city of Friborg to the year 2000 with information in brackets). At the university, there is a balanced linguistic relationship between German and French speakers, plus several hundred students from Italian-speaking Switzerland and numerous international guest students.

Unlike the officially bilingual canton of Friborg, the city of Friborg is politically a French-speaking municipality with a significant German-speaking minority. For many years, German-speaking residents of the city and canton have been trying to make the municipality of Friborg officially bilingual. Requests in this direction have so far been rejected by the municipal council.

In contact with authorities, however, you can communicate in both French and German. Schools in both languages can also be attended. In 2008, a “Forum Languages” was initiated by some city parliamentarians, which aims to promote the exchange and rapprochement between languages. In 2013 the station was officially labeled “Friborg / Freiburg” and will appear in all timetables and tariffs in future. Unlike Biel / Bienne , which is officially bilingual, Freiburg is still in a development process when it comes to the language issue.

Freiburg was always on the linguistic border , the so-called " Röstigraben ", but the German language was predominant when the city was founded in the 12th century. Although German was the official language in the city until 1798 and rich families Germanized their names - Bourquinet became Burgknecht, Cugniet became Weck, Dupasquier became Von der Weid - French gradually gained in influence. With new factories, an attraction for French-speaking workers was created. Since the political upheavals at the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century, the German-speaking residents were pushed into the minority and discriminated against for some time. In the lower town (Basse-Ville), where the poor population once lived, there used to be a German-French mixed language, the Bolz . The pressure to assimilate was high and not infrequently associated with strong feelings of inferiority. The few economically successful climbers, such as racing driver Jo Siffert , were almost completely acculturated .

Against the will of the residents, the 147-soul village of Tafers was raised to the district capital in 1848 , which weakened Freiburg's German-speaking people politically and culturally, as they were now separated from their most important area. Exact figures on the linguistic relationships have only been available since 1888. At that time, around 37% of the city's population said German as their mother tongue. From 1909 German-speaking teachers could be trained in Altenryf near Freiburg, before they had to move to Zug and Rickenbach . Since 1950 in particular, the proportion of German speakers has fallen sharply due to the influx of people from the French-speaking rural areas west and south of Freiburg. The city expanded mainly towards the west. Nevertheless, efforts have been made to maintain bilingualism since the middle of the 20th century. In 1968 the Freiburg Institute published a charter for linguistic peace.

Religions

The population of Freiburg is predominantly Roman Catholic . In 2000, 69% of the residents were Catholics, 9% Protestants, 14% belonged to other faiths and 8% were non-denominational. The city remained Catholic during the Reformation and formed a political and intellectual center of Swiss Catholicism , which was strongly networked internationally, into the 20th century . The city has an above-average density of churches and monasteries, and Freiburg has been the seat of a bishopric since 1613 . It was and is partly still beside the great religious and branches of the Fathers of the Holy Sacrament , the Redemptorists , Carmelites , Salvatorian , Salesians , Pallottiner , Maria Hiller , the White Fathers , Little Brothers of the Gospel , Marianists , Vincentians , Society of the Divine Word , the Missionaries of Bethlehem , the Sisters of Canisius , the Filles de la charité de Saint-Vincent-de-Paul , Sisters of Divine Providence , or, for example , the Sisters in Bride . Freiburg was the control center and refuge for Catholic conservatives from all over Europe (for example the Union de Friborg , Pax Romana ). Members of the Polish and Lithuanian upper classes came to the city in large numbers in the course of the partition of Poland and during the Second World War , which had devoted itself to training a Catholic elite. From 1942 to 1946 there was a university in exile for Polish internees in the Saint-Louis foyer. In and around Freiburg, a veritable archipelago of Catholic boarding schools emerged from 1825, mainly for girls. These institutes flourished because of the state-ordered closure of the Jesuit schools in France. The boys 'and girls ' boarding schools that existed from Givisiez , at the north entrance of the city ( La Chassotte ), to Estavayer-le-Lac (from 1836) and Montagny-la-Ville , are now mostly empty or have been, as in the case of the Villa Saint-Jean , demolished in 1981. To the Catholic Freiburg and social works were like the Villa Beausite, agricultural institutes, printers and properties undergoing church property Catholic newspaper La Liberté and Freiburger Nachrichten , as well as in the culture war based organization Swiss Catholic Press Association . There was also the influential Cercle catholique of the ultramontane conservatives in Freiburg from 1874 and the Catholic international press agency from 1917 . The influence of the church has greatly diminished; In 1970, only 403 people in the canton of Friborg reported being non-denominational , this number rose to 41,200 in 2015. Part of the reason for this decline are also numerous cases of child abuse in the Catholic children's home Institut Marini in Montet , which occurred between 1929 and 1955 are documented.

The Evangelical Reformed congregation was founded in 1836, the first pastor of which was Wilhelm Legrand , but only got its own church building in 1875, which is located at the entrance to the old town. The community, originally organized under private law, has belonged to the Evangelical Reformed Church of the canton of Friborg since 1854 . The services are held separately in both languages, other activities are bilingual. Many initiatives for urban development came from the Protestants, for example the founding of the Daler Hospital by the merchant Jules Daler. In addition, several Protestant free churches are active in Freiburg today .

The Christian Orthodox community has a church in the back yard of the editorial building of the newspaper La Liberté on Boulevard de Pérolles. The community belongs to the Metropolitan Switzerland of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople . Numerous Eritrean Orthodox Christians are currently living in the city.

After Jews were banned from settling in Freiburg for centuries after the pogroms of the early modern period , a new Jewish community ( Communauté israélite de Friborg, CIF) was founded in 1895 by immigrants from the Surbtal and Alsace , which has existed to this day and has been today since 1904 Synagogue owns. In 2006 the congregation had 62 members. It is one of the smallest communities in Switzerland and belongs to the Swiss Association of Israelites . The community is orthodox as far as possible and has a regular minyan , but it does not have its own rabbi or chasan .

There is also a Muslim community ( Association des Musulmans de Friborg, AMF) and an Alevi association.

The Saint-Léonard cemetery was laid out from 1901 to 1903 according to plans by the architect Isaac Fraisse. Sectors 1 and 2 date from this time. A first extension based on the pattern of a forest cemetery took place in 1923 according to plans by landscape architect Adolf Vivell . The second expansion in 1972 gave the cemetery its present form. The Saint-Léonard cemetery includes parts for the Catholic, Protestant, Jewish and Orthodox religious communities. Well-known personalities are buried here, for example Jules Daler, Athénaïs and her brother Gustave Clément, Bruno Baeriswyl or Armand Niquille . The cemetery is one of the cultural assets of regional importance.

politics

legislative branch

| Political party | 2021 | 2016 | 2011 | 2006 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SP | 23 | 30th | 24 | 22nd |

| Green | 21 | 8th | 10 | 9 |

| CVP | 14th | 15th | 17th | 23 |

| FDP | 8th | 10 | 10 | 8th |

| SVP | 6th | 9 | 8th | 9 |

| CSP | 7th | 5 | 6th | 7th |

| glp | CVP | 1 | 1 | - |

| Various | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Total | 80 | |||

The legislative authority is the General Council (conseil général) elected every five years by the voters of the municipality of Friborg . The 80 MPs are elected by proportional representation. The tasks of the General Council include the budget and invoice approval, the establishment of the municipal regulations and the control of the executive.

executive

The executing authority is the municipal council (conseil communal) . It consists of five members and is elected by the people in a proportional voting process. The number of members was reduced from nine to five in 2001. The term of office is five years. The municipal council is responsible for the enforcement of the resolutions of the general council, for the implementation of federal and cantonal legislation as well as for the representation and management of the municipality. The city administrator (Syndic) has extended competencies. He chairs the meetings of the municipal council.

The five incumbent municipal councils are (legislative period 2016-2021):

- Thierry Steiert (SP): Stadtammann (Syndic)

- Antoinette de Weck (FDP): Vice-Mayor (Vice-Syndic)

- Laurent Dietrich (CVP)

- Pierre Olivier Nobs (CSP)

- Andrea Burgener Woeffray (SP)

National Council elections

In the 2019 Swiss parliamentary elections, the share of the vote in Freiburg was: SP 29.45% (main list 22.88% + four youth and diversity lists 1.74 / 1.36 / 0.48%, Juso 2.99%), GPS 20.85%, CVP 15.50% (main list 12.40% + four youth lists 1.36 / 0.31 / 0.69 / 0.74%), SVP 9.65% (main list 9.27% + a youth list 0.38%), FDP 9.13% (main list 8.50% + a youth list 0.63%), CSP 5.61%, GLP 5.54% (main list 3.88% + a youth list 1.66%), EVP 0.48%, BDP 0.36%, EDU 0.30%. Four other lists accounted for a total of 3.14%. The turnout was 46.59%.

Community merger

A constitutive assemblée was convened in 2017 to discuss a possible community merger under the project name Grand Friborg . It is the task of the delegates to jointly define the outlines of the future congregation within the framework of a merger agreement.

business

Development of trade and economy

Various branches of industry developed in Freiburg as early as the 13th and 14th centuries. The city expansions on the eastern bank of the Saane that were carried out at this time indicate a strong economic upswing. In the Galtern Valley in particular, water power was used to operate mills, saws, hammer forges, fulling machines and stamping mills. Commercial quarters were also created along the Saane with the districts of Au, Neustadt and Matten. This “lower town” (Basse-Ville) remained a workers' quarter until the most recent times, when picturesque old buildings became chic , and until the 1950s it was even one of the poorest regions in Switzerland.

In the 14th and 15th centuries, the tannery and cloth-making , supported by sheep farming, which was widespread in the region at the time, led to an actual economic boom . They made Freiburg famous throughout Central Europe thanks to the trade in goods. The gradual decline in cloth production began in the second half of the 15th century, when sheep breeding was more and more replaced by cattle breeding . Further reasons for the collapse of the cloth industry in the 16th century are that the guilds (French: Abbayes ) refused to adopt new fabrics and fashion trends and that the social structures in the city changed with the rise of the patriciate . Another cause was the decline of the trade fairs in Geneva, so that the sale of the goods was hampered.

In the period that followed, Freiburg was shaped by small businesses. The industrialization took until after the connection to the Swiss railway network of the 1870s on foot. Many companies were founded by Protestant immigrants, as the Catholic city elite was averse to any industry because they feared the emergence of a left-wing proletariat . After the Pérolles lake was dammed in 1872, energy could be delivered to the Pérolles plateau south of the city and west of the Saane. An industrial area was created on this plateau, which was initially dominated by a sawmill and a wagon factory . Two breweries were founded in 1877 and 1883 and merged in 1970 to form Sibra Holding AG. 1901 was on the floor of Villars-sur-Glane , the chocolate factory Chocolat Villars added. This has been in the city area since an assignment in 1906. Sinalco lemonade was produced from the 1960s . It was dominated by the agriculture-related food industry, which also produced apple juice ( Mosterei Düdingen ) and milk powder ( Epagny ) in the canton . In the retail sector, the Nordmann family took several initiatives to found department stores ( Manor ) from 1885 onwards .

In the course of the 20th century, the Pérolles plateau, which also had a rail connection, developed into an industrial quarter. With the development of new industrial zones outside the municipal area, various industries were relocated to the outskirts of Givisiez , Granges-Paccot and Villars-sur-Glâne from the 1970s . Industry was able to take up a larger space here and was given better road connections (proximity to the motorway), while the vacant areas near the center could be converted into residential and shopping areas.

The La Pila landfill just outside the city was used for disposal from 1952 to 1973 and is now one of the six largest contaminated sites in Switzerland. Because PCB flows into the Saane, the landfill is to be renovated from 2022.

Situation today

Today Freiburg offers around 25,000 jobs. With 0.6% of the workforce who are still employed in the primary sector, agriculture only has a minimal role in the employment structure of the population. Today she focuses on dairy farming , cattle breeding and some arable farming . Around 17% of the workforce is employed in the industrial and commercial sectors , while the service sector accounts for around 82% of the workforce (as of 2001).

Friborg has a strong surplus of commuters and is a regional attraction for residents in the largely agriculturally dominated surrounding area as well as from Bern and Lausanne . The industry based in Freiburg has now specialized in the food and beverage, pharmaceutical, metal and mechanical engineering sectors, as well as in electrical engineering, electronics and microtechnology. The construction industry is also well represented. In contrast, the Cardinal brewery is now owned by the Danish company Carlsberg , which brews Cardinal beer in Rheinfelden . The brewery's facilities were largely dismantled. There is currently a transitional use through cultural areas and the Blue Factory innovation promoter .

The largest number of employees work in the service sector, a large proportion of them in the public services ( SBB , TPF , Groupe E , post office , city and canton). Other important sectors are the education system with the university, branches of banks and insurance companies with the headquarters of the Freiburger Kantonalbank , the retail trade, the tourism and catering industry (e.g. Villars Holding ) as well as the health care system. Because of its location on the language border, various call centers have chosen Freiburg as their location. In addition to the two local newspapers La Liberté and Freiburger Nachrichten , Radio Friborg also has a local radio station and offices of various Swiss television stations. The low-tax neighboring municipality of Villars-sur-Glâne is the seat of administrative branches of internationally active companies. The Friborg Cantonal Hospital is located on the municipal boundary, but for the most part in the area of Villars-sur-Glâne.

Culture and tourism

The city of Freiburg is an attraction for day tourists who want to visit the sights of the city. Tourist attractions are the historic old town on its striking spur above the Saane valley with the Gothic St. Nicholas Cathedral with the famous glass windows by Józef Mehoffer and the museums.

The Natural History Museum Freiburg was founded in 1873 and is now located next to the Botanical Garden in one of the buildings of the Natural Science Faculty of the University of Freiburg in Pérolles. In the Museum of Art and History (Musée d'art et d'histoire), which has been housed in the Ratzéhof since 1920, you can see important collections from prehistory and early history, archeology, sculpture and painting, traditional pewter figures, arts and crafts as well as coins and Visit graphic collections.

A treasury has been open in the cathedral since 1992. The Espace Jean-Tinguely-Niki-de-Saint-Phalle , which has been in the former tram depot since 1998, shows works by the artist couple. Other museums include the Fri-Art art gallery , the Swiss Puppet Theater Museum (Musée suisse de la Marionnette), the Swiss Sewing Machine Museum (Musée suisse de la Machine à Coudre), the Gutenberg Museum of the Swiss Graphic Industry and the Cardinal Beer Museum . The Friborg Cantonal and University Library also shows changing exhibitions . The university has the small Bible and Orient Museum in the Miséricorde .

Cultural events include the biennial International Festival of Sacred Music, the International Folklore Meeting , the Belluard Bollwerk Festival , the International Film Festival in the Rex and Arena cinemas, and Cinéplus (since 1978). In addition, contemporary art finds its place in the WallRiss art- off space , as well as electronic and rock music in the Fri-Son . Other places of youth and student culture are the Center Fries , the Café Culturel de l'Ancienne Gare (Le Nouveau Monde) in the old train station, the La Spirale jazz club or the Keller Poche small theater . Current music is also offered by the Bad Bonn Kilbi Festival in neighboring Düdingen, the Les Georges Festival and the winter open-air Le Kopek Festival, which got into negative headlines because of its former name (“Le Goulag Festival”) .

The Forum Friborg exhibition and congress center, which opened in 1999, is located next to the Casino Barrière in the municipality of Granges-Paccot on the northern outskirts of the city. It is the venue for the Freiburg trade fair.

The Équilibre cultural center for theater, concerts, opera and dance has existed in Freiburg since December 2011 . It presents its program in cooperation with the Nuithonit Theater in Villars-sur-Glâne. They organize the FriScènes festival every year .

Every year on the first Saturday of December, the traditional St. Nicholas Festival takes place, which attracts up to 20,000 people to the streets of the city center. The 100th edition was celebrated at the beginning of December 2005. The Concordia (the city's harmony orchestra) and the Landwehr (a music band performing in uniforms) as well as the student associations that still exist today , such as the AKV Alemannia , also have a long tradition .

education

Since the founding of the Jesuit College of St. Michael in the 16th century and the establishment of the bilingual University of Freiburg in 1889, Freiburg has acquired the reputation of an important educational city. All school levels in Freiburg can be attended in German or French. In Friborg - unique in Switzerland - there is also the possibility of a bilingual university degree or the possibility of studying without a Matura . University of applied sciences degrees are also possible in both languages. The focus of educational work shifted from Catholicism to bilingualism in the second half of the 20th century .

The city has three grammar schools, the Collegium Sankt Michael , the Kollegium Heilig Kreuz and the Kollegium Gambach . In addition to the university, the secondary schools that are based in Friborg include the Ecole de Multimédia et d'Art de Friborg (EMAF), the Freiburg teaching workshop (Ecole des Métiers de Friborg, EMF), which specialize in the fields of technology, Computer science, electronics, automation and polymechanics concentrated, the engineering and architecture school, the university for economics and administration , the university for health and social work, the pedagogical university and the conservatory . The language center of the university and z. B. the adult education center complement the educational offer.

traffic

Friborg is the most important traffic junction in the canton of Friborg. The city is located on the main road 12 , which leads from Bern to Vevey . Further main road connections exist with Payerne , Murten and Thun . The connection to the Swiss motorway network took place in 1971 with the opening of the A12 motorway from Bern to Matran . The autobahn has been continuously passable from Bern to Vevey since 1981. Freiburg was then on the main axis of road traffic from Bern to western Switzerland for 20 years until the opening of the A1 . The motorway bypasses the city in the north and west and only affects the municipality in a short section in the valley west of the heights of Chamblioux. The Friborg-Sud and Friborg-Nord junctions are each around 3 km from the city center. The Poya Bridge , opened in 2014, relieves the old town of car traffic.

The connection to the railway network took place in several steps from 1860 onwards. First, the Lausanne – Bern line was put into operation on July 2, 1860. However, the provisional terminus at the time was near the hamlet of Balliswil, around four kilometers north-northeast of the city. The Grandfey Viaduct over the Saanegraben was not yet completed at that time. A good two years later, on September 4, 1862, the entire line from Balliswil via Friborg to Lausanne was opened. The Freiburg train station was initially only a temporary solution until the actual building was erected in 1873. Further routes were opened on August 25, 1876 (Freiburg – Payerne) and on August 23, 1898 (Freiburg – Murten). The connection from the Neuveville district to the Upper Town has been made since 1899 by the Neuveville – Saint-Pierre funicular, which is operated with sewage (see also water ballast railway ). From 1897 to 1965 the approximately six kilometer long tram was in operation in Freiburg . From 1951, however, it had to give way to the trolleybus that opened in 1949 . However, between 1912 and 1932 there was an overland trolleybus line, the Gleislose Bahn Freiburg – Farvagny . The new train station Friborg-Poya brings ice hockey fans directly to the stadium.

The beginnings of a transport association in Freiburg go back to February 1, 1996. On this day, the transport companies joined forces with those of the Freiburg agglomeration to form the Communauté urbaine des transports de l'agglomération de Friborg (CUTAF) and adopted the statutes. Operations started with the timetable change on June 29th. In addition to the city of Friborg, which carried 70% of the traffic load, the municipalities of Villars-sur-Glâne (16%), Marly (4%), Granges-Paccot and Givisiez (3% each) as well as Avry, Belfaux, Corminbœuf, Düdingen, Matran, St.-Ursen and Tafers (all below 1%) in addition.

Today, a dense network of public transport services in the city of Freiburg provides for the fine distribution of public transport . It consists of three trolleybus lines and four additional bus lines. When the timetable changed in December 2012, the former intercity buses No. 542 (new No. 8), No. 575 (new No. 9) and No. 338 (new No. 11) were added to the city bus network. Furthermore, regional bus routes run from the city in a star shape in all directions of the canton , including to Bulle , Avenches , Schmitten , Schwarzenburg and the Schwarzsee tourist region .

Since 2010 there has been a public network of three bike rental stations. There are 32 city and electric bikes available. The stations are located at the train station, at St-Léonard and at the Uni Pérolles. Day tickets can be obtained from the tourist office or from the TPF counter at the train station. The PubliBike network has now been expanded to include a total of 25 bike rental stations in the Freiburg agglomeration (as of 2019).

story

See also the main article: History of the Canton of Friborg

prehistory

The region of Freiburg has been settled since the Neolithic Age, but only sparse finds come from today's urban area, for example some flint finds near Bürglen as well as stone ax blades and bronze tools . During the Roman period there was a crossing over the Saane near Freiburg. At that time, however, the main axis through the Mittelland ran further north through the Broyetal and via Aventicum (Avenches). That is why only minor traces of settlement have survived from the Roman era. Some remains of Roman wall foundations have been discovered on the Pérolles plateau.

middle age

Freiburg was founded in 1157 by Duke Berthold IV of Zähringen in a strategically well-protected location on a rocky promontory above the Saane and given generous freedom. The Zähringer were able to consolidate and expand their position of power in the Swiss plateau in the area between Aare and Saane. The first recorded names of the city are Friborc (1157/80) and Fribor (1175). Friborg en Nuithonie has been handed down as a French name . The name, which means "free city", is intended on the one hand to refer to the privileges that the city's founder bestowed on the citizens, but on the other hand to be a deliberate imitation of Freiburg im Breisgau , which was also founded a little earlier by the Zähringers .

From its inception, Freiburg has been a city-state, i.e. a city rulership, to which hardly any area from the surrounding area belonged. When the family of the Zähringer died out in 1218, Freiburg passed to the Counts of Kyburg through inheritance . This granted the city its previous freedoms and wrote the municipal constitution in 1249 in the so-called handfeast , in which the legal, institutional and economic organization was recorded. During this time, several alliances were concluded with the neighboring cities of Avenches (1239), Bern (1243) and Murten (1245).

The town came to the House of Habsburg through purchase in 1277 for 3,040 marks of silver and thus became its westernmost base in competition with the House of Savoy for power in the region and was repeatedly involved in wars with the Dukes of Savoy and Bern. The attempt of Friborg in league with the Savoy and various other noble houses in the region to oppose Bern's expansion policy failed on April 21, 1339 with the defeat in the Battle of Laupen . Trade and industry flourished as early as the middle of the 13th century. In the early days, Freiburg consisted of four different quarters: Burg, Neustadt, Au and Spital. The city developed rapidly and underwent the first expansions: the castle district expanded further west as early as 1224, the bridgehead was founded on the east side of the Bern Bridge in 1254 and from 1280 expansions were made in the area of today's Place Python. These extensions reflect the economic upswing in Freiburg. In the 14th century Freiburg became an important center of trade, cloth production and leather processing, which helped the city to become known throughout Central Europe from 1370 onwards.

On February 12, 1378 Jakob von Düdingen sold his share in the Simmental to the city of Freiburg for 3000 guilders . On February 24th, Wilhelm von Düdingen also undertook to keep his castles in the Simmental ( Blankenburg , Mannenberg and Laubegg ) open for the city of Freiburg . At the same time, Count Rudolf von Kyburg pledged the city of Freiburg for 5000 guilders for the castle, town and rule of Nidau . On May 16, 1382, the city of Freiburg was able to buy Inselgau (Seeland) for 1050 guilders. These included Worben, Jens, Merlingen, Bellmund, Wiler, Port and the bailiwick over St. Petersinsel . All these acquisitions in addition to the old landscape would have resulted in a solid foundation stone for the territory of the city-state of Freiburg. But they were lost to Bern after the Sempach War and a real guerrilla war developed between Freiburg and Bern. Finally, in the peace treaty between the Confederates and the Habsburgs of April 1389, the Freiburg citizens not only lost their claims to Büren an der Aare and Nidau as well as to the Simmental. After long, tough arbitration negotiations, they were also denied Inselgau on February 18, 1398.

The castle law treaty with Bern was renewed in 1403. The city lords now pursued a new territorial policy by gradually acquiring areas in the immediate vicinity and thus laying the foundation for the Freiburg Old Landscape. As early as 1442, the city created an area around 20 km in diameter on both sides of the Saane. Subsequently it was directly subordinate to the city lords and was not administered through the intermediate stage of a bailiff.

The time around the middle of the 15th century was marked by various armed conflicts. First of all, there were major losses in the war against Savoy . The Savoyard element gained more and more influence in Freiburg, and so in 1452 the town came under the sovereignty of Savoy from Habsburg, in which it remained until 1477 after the Burgundian Wars . As an ally of Bern, Freiburg took part in the wars against Charles the Bold and was thus able to secure further areas for itself. On September 10, 1477, Duchess Jolande of Savoy released Freiburg from Savoyard rule and shortly thereafter on January 31, 1478, the city received imperial immediacy. From that time on, Freiburg, with its territory, the "Old Landscape" and the dominions of Montagny and Illens / Arconciel acquired from 1475–1478, formed a city with the status of a free imperial city . Together with Bern, Freiburg ruled the dominions of Grasburg , Murten , Grandson and Orbe-Echallens .

Heretic trials against the Protestant Waldensians took place in Freiburg in 1399 and 1429–1430 . The defendants were tortured and forced to wear yellow disgraceful cloth crosses on their chests and backs. Four women were imprisoned for life, one Waldensian was sentenced to death at the stake . The internationally successful trading house of the Perroman Society (also: Praroman-Bonvisin ), whose members were considered to be Waldensians, was expelled from the city. From 1400 onwards, authorities made Freiburg the scene of several witch trials . Friborg has been a member of the Swiss Confederation since 1481 . In the 16th century, Freiburg was able to record further territorial expansion, first in 1536 with Bern when conquering Vaud and in 1554 when the bankrupt county of Gruyères was divided up .

Various rich families emerged from the cloth and leather trade since the end of the 14th century, including Gottrau, Lanthen, Affry, Diesbach (originally from Bern, after the Reformation also in Freiburg), Von der Weid, Techtermann, Fegeli and Weck. Together with the local nobility (families Maggenberg, Düdingen / Velga, Montenach, Englisberg and Praroman), the patriciate was formed from the 15th century , which subsequently divided power among themselves. Exactly this was an important reason for the decline in the production of cloth, because the families, who had once risen through trade and commerce, now increasingly took care of the city rulership and the administration of the acquired and from now on continuously rounded off land. A milestone in city politics is the year 1627, in which the patriciate of the time declared itself eligible for regiment with a new constitution and thus claimed the active and passive right to vote for itself. This sealed the oligarchy with restrictive organizational structures that had already emerged in the course of the 15th century.

The importance of churches and monasteries in the city

The monasteries of Freiburg always formed a center of spiritual culture, were responsible for architecture, sculpture and painting and contributed significantly to the prosperity of the city. The monastery of the Franciscan Conventuals was donated by Jakob von Riggisberg in 1256 as a monastery of the Franciscan Order founded in 1210 and, when the order was divided in 1517, it joined the direction of the Conventuals, who follow a moderate form of the vow of poverty . In its early days, it was closely linked to the city council by keeping the city archives until 1433 and making the monastery church available for citizens' meetings. Of particular importance is the dance of death , which the Freiburg painter Pierre Vuilleret painted between 1606 and 1608 on the south wall of the monastery cloister . The originally 17 murals showed how death confronts several notables in order to take them with it. The client was the knight Hans von Lanthen-Heid. The remnants of these murals were removed in 1927 in order to make the underlying late Gothic cycle of a life of Mary visible again. Today the scenes of the dance of death can still be recreated because two watercolors from 1875 by the Solothurn painter Adolf Walser and 16 gouaches from 1925/26 by the Franciscan Maurice Moullet have survived.

The Augustinian monastery in the Au was also founded around the middle of the 13th century and enjoyed the support of the Velga family for a long time. The women's monastery Magerau (Maigrauge) has also existed since 1255. It has belonged to the Cistercian order since 1262 and is subordinate to the Hauterive monastery.

An important institution was the citizen's hospital founded in the middle of the 13th century, which took care of the care of the Arbareössigen and was given a new building on Rue de l'Hôpital from 1681 to 1699. From 1260 a commander with an attached hospital was built under the Johannitern .

During the Reformation period , Freiburg stayed with the old faith, although its area was almost completely surrounded by the now reformed Bern. In 1524 the entire population was forced to take a professio fidei , a public Catholic creed. In the border areas and in the lordships administered jointly with Bern, there were repeated disputes about the denomination. The northern areas around Murten turned to the Protestant denomination . The city of Freiburg itself became a stronghold of the Counter Reformation . In the period from the end of the 16th century to the first half of the 17th century, various new monasteries were founded, namely the Capuchin Monastery (1608), the Capuchin Monastery on Bisemberg (1621), the Ursuline Monastery (1634) and the Visiting Monastery (1635) .

The most influential order, however, were the Jesuits , who made a decisive contribution to the development and prosperity of the city. Under the direction of the Dutchman Petrus Canisius , the Englishman Robert Andrew and the Silesian Peter Michel, they established the Saint Michael College in 1582 , which with its theological faculty represents the origin of the University of Freiburg . The college, which was built on the bisexual hill in three construction phases up to 1661, was expanded by the Jesuits in 1673 to become a law school. The development of the official print shop can also be traced back to her initiative. The order, banned by Pope Clement XIV in 1773, was allowed to return to the city on September 15, 1818 at the instigation of the patriciate under the leadership of Philippe de Gottrau and made it a stronghold of the Restoration . This also withdrew the influence of more open-minded clergymen, such as the Franciscan Father Jean Baptiste Girard , from innovations .

From 1613 onwards, Freiburg became the residence of the Bishop of Lausanne, who after the Reformation of Lausanne stayed first in Evian and then in exile in Burgundy. Today Friborg is the seat of the diocese of Lausanne, Geneva and Friborg .

Modern times

The strict patrician regime (consisting of a maximum of 60 families) held all influential posts in the city for almost 200 years and played the leading role in political, economic, cultural and social terms. The oppressed citizens banded together several times and rehearsed the popular uprising, including in 1781 under the leadership of Pierre-Nicolas Chenaux . With the support requested by Bern, the uprising could be put down. The elite were closely linked to the French monarchy and largely financed their lifestyle with pensions for the delivery of mercenaries to the Bourbons . The Swiss killed in the storming of the Tuileries Palace in 1792 were under the command of Louis Augustin d'Affry from Friborg . Franz Peter König von Mohr (1594–1647) is an exception: he came from a rather modest family, served in the imperial army of the Habsburgs during the Thirty Years' War and made it to the mayor of Freiburg.

When the French troops marched into Switzerland in 1798, the end of the Ancien Régime was ushered in. Freiburg surrendered on March 2nd and had to resign its rule over the landscape. This cleared the way for the election of a local authority, which was the first mayor of the city, Jean de Montenach . With the introduction of the act of mediation under Napoleon , the canton and municipality of Friborg were separated in 1803. On June 28, 1803, the Constitutio Criminalis Carolina of 1532, which z. B. Torture , quartering and wheels envisaged that in the Helvetic Republic had been banned, re-introduced under pressure from the conservatives.

The city was the capital of the district and the canton and, between 1803 and 1809, alternately one of the capitals of Switzerland. The social life of the rich upper class took place in their summer palaces and in winter in the winter societies of the guilds and the circles : in the aristocratic Grande Société from 1802, in the liberal Cercle littéraire et de commerce from 1816, and later also in the liberal-conservative Cercle de l'Union (1841) and conservative Cercle catholique (1874). Numerous wine and schnapps taverns were open to the lower class, in which prostitution , which was declared illegal, by women and girls from the poverty-stricken lower city of Freiburg was tolerated.

The years 1816 and 1817 brought bad harvests and increasing social misery. At the same time - despite repression and spying - the fear of a revolution increased, as several Freiburg officers had witnessed at close quarters in Paris. The patriciate therefore sought an understanding with the titular emperor of Brazil , the Portuguese King John VI . and agreed with the regent interested in Catholic immigrants in 1818 to found the colony Nova Friburgo . 830 Freiburg residents left the country for Brazil on July 4th of the following year, along with other Swiss (around 500 Bernese, 160 Valais , 140 Aargau and Lucerne residents ). However, around a fifth of these emigrants died of typhoid , malaria and other diseases on the way to the new colony . Emigration, later to Argentina and Chile , was a social outlet that stunted economic development. In 1845 every fourth employee in Freiburg was a servant or a maid. Many residents also moved to more industrialized areas of western Switzerland . Nova Friburgo is today a twin town of Freiburg.

In 1814 the old patrician rule came to power again and ruled the city during the restoration period and until the abolition of the patriciate under the later mayor Joseph de Diesbach-Torny in 1830. After that, the regime was replaced by a more liberal cantonal constitution and in 1831 the German-speaking Sense district , where the peasants continued to be leased to the city lords, politically more independent. In 1830 the Swiss regiments in the service of France were disbanded, after which many Freiburgers joined the Foreign Legion from 1831 . Freiburg, which took part in the Sonderbund as a city and canton , was one of the scenes of the Sonderbund War and had to capitulate on November 14, 1847. The Jesuits, who from a liberal point of view were agents of the Vatican and conservative powers - such as Austria - were expelled, their estates were nationalized and their extremely profitable boarding school plundered. On April 22, 1853, several hundred Catholic-Conservative peasants under the leadership of the former teacher Nicolas Carrard attempted a coup against the liberal government of Julien Schaller , which ended with the deaths of Carrard and 13 other rebels. From 1848, with the new federal constitution and the amendment to the cantonal constitution in 1857, every resident Swiss citizen had the right to vote in Friborg.

From February 2 to March 15, 1871, 3,700 interned French members of the Armée de l'Est , the so-called Bourbakis, were quartered and cared for in Freiburg. In addition there were 628 horses that were housed in the city and the surrounding area. 81 internees did not survive the hardships. A cemetery was established for them in the Neigles. Oswald Corvinus Szymanowski, son of a Pole who fled to Switzerland after the November uprising in Poland in 1830, provided exemplary and generous help, which the population also joined. The fact that Switzerland gave a foreign army a refuge by interning it helped to define armed neutrality on an international level and enabled young Switzerland to distinguish itself as a humanitarian country.

Freiburg only introduced cantonal women's suffrage on February 7, 1971, at the same time as it was introduced at the federal level. A cantonal advisory service for family planning and baby care has existed since 1983 . Two years earlier, the legal basis that had led to a large number of administrative provisions for unmarried mothers in the canton since the second half of the 19th century had been abolished . Children of politically dissenters , poor people , habitual drinkers (“buveurs d'habitude”) and so-called work-shy were also affected by the roadblocks. The Bellechasse prison , in the northern canton, served the Freiburg authorities to implement these measures, which were applied throughout Switzerland. This practice was justified with the protection of morality and public order .

Extremely conservative positions held up in Freiburg for a very long time. From 1856 to 1966, conservative forces were again in power without interruption. In particular, the reign of Georges Python was characterized by anti-liberalism. This was also expressed in several campaigns against the communists and freemasons that did not exist in Freiburg. At the same time, elementary school enjoyed little priority over church education. The self-image of the canton of Friborg, defined as the “République chrétienne” (Eng. “Christian Republic”), also included the fact that during the Spanish Civil War, money collections for the putschists under General Franco were coordinated. Later senior members of the Algerian OAS found refuge in the city, and collaborators and apologists for the Nazi occupation ( Bernard Faÿ , Yves Bottineau ) were offered places to work. During the Vietnam War , hundreds of sons of the then predominantly French-speaking South Vietnamese elite continued their studies in Freiburg. Domestically, Freiburg was a stronghold and center of attraction, especially for the Valais conservatives, and with Jean-Marie Musy and Gonzague de Reynold produced the loudest advocates of the corporate state . The organization Opus Dei has been active in Freiburg since 1966 .

In the course of the 19th century there were drastic changes in the cityscape. From 1848 the city walls were partially torn down and new bridges spanned the Saane and Galtern valleys. The connection to the Swiss railway network from 1862 led to the creation of a station district. With the improved transport connections, industrialization also prevailed. The center of gravity of the city thus shifted from the historic old town to the station district. Large areas in the quarters of Pérolles, Beauregard and Vignettaz were built over with industrial plants and residential buildings around 1900. The opening of the university in 1889 was an important cornerstone. Between 1950 and 1965, the share of the primary sector (agriculture) in the canton fell from 35.4% to 23.2% of the working population. At the same time, the share of those employed in industry rose from 34.5% to 43.6%. Freiburg received further impetus in the economic upswing in 1971 with the opening of the first section of the A12 motorway from Bern to Vevey. Today, the public space in Freiburg is strongly influenced by the consumer society , with several large shopping centers in and around the city, and by a considerable volume of traffic. Today, Friborg is successfully asserting itself as an agglomeration between Lausanne and Bern.

Cityscape and landmarks

Freiburg was able to keep its old historical city center. Today it is one of the largest closed medieval centers in Europe and is located on a spectacular rock ledge, around which the Saane flows on three sides. Most of the building fabric dates from the Gothic period up to the 16th century; the houses are made mostly from regional molasses - sandstone . The core of the old town is the castle quarter, but the Auquartier (also in the Saane loop, but only around 10 m above the valley floor) and the bridgehead east of the river at the beginning of the 13th century were added in the 12th century. This slightly angled city plan is around one kilometer long, but only around 100 to 200 m wide.

The city was protected by a system of circular walls that was at least two kilometers long and fitted well into the difficult topography. Important witnesses of this medieval military architecture in Switzerland are, in addition to the remains of the wall, 14 towers and a large bulwark from the 15th century. The former fortifications are particularly well preserved in the east and south. These include the Bern Gate Tower, the Katzenturm, the Red Tower (from the 13th century) and the Dürrenbühlturm. The Murtentor (1410), the four-pound tower (Tour des Rasoirs, 1411), the Tour des Curtils novels and the semicircular Thierry Tower (Tour Henri, 1490) at the Miséricorde in the northern and western parts of the city are somewhat more recent .

The St. Nicholas Cathedral is an outstanding building in the old town of Freiburg . It was built in several stages from 1283 until 1490 on the site of a Romanesque church.

In the castle district are numerous other important buildings. The town hall (Hôtel de Ville) was built between 1501 and 1522 on the site of the former Zahringi castle, which was destroyed in the 15th century. Its clock tower was changed several times in the 16th and 17th centuries. Right next door is the town house from 1731, a mixture of styles from Baroque and Classicism . The State Chancellery (1734–1737) also shows the same styles and a sculpted heraldic motif above the main portal. The town hall square with the Georgsbrunnen (fountain figure from 1525) is also lined by the gendarmerie, a Louis-seize-style building from 1783. The post office building from 1756-1758 shows the Louis XV style. The market was and still is held in Hauptstrasse (Reichengasse, French Grand-Rue ). The street is lined by an impressive group of houses from the 16th to 18th centuries, including the administrative building of the municipal authority with styles from Gothic and Renaissance , the Castella house (1780) and the late Gothic building Les Tornalettes (1611–1613) with a stair tower and Corner bay window. The Techtermann house, which basically dates from the 14th century and is therefore the oldest residential building in the city, and the Hôtel Zaehringen from the 18th century are located on Zähringerstrasse.

A number of important church buildings can be found in the Upper Town , the former hospital district on Murtengasse. The core of the three-aisled Church of Our Lady (Notre-Dame) dates back to the 12th century, but was extensively redesigned from 1785 to 1787. The baroque-classicist facade dates from this time, while the bell tower still shows its original structure and in the substructure there is a Romanesque-Gothic chapel from the 13th century. The Franciscan Church (originally from 1281) with its three-aisled Gothic choir is also worth seeing; the nave and the outer facade were renewed in 1735–1746. The rich furnishings include the wooden choir stalls from 1280, which are among the oldest in Switzerland, and a high altar from the 15th century. In the cloister there are frescoes from around 1440. Somewhat more recent are the monastery and church of the Visitandesses, which were built between 1653 and 1656. The central building of the convent church, which is crowned by an octagonal drum dome, is remarkable. The church of Saint Michael, which belonged to the Jesuits, was built in the late Gothic style in 1604–1613, while the interior was redesigned in the mid-18th century and given Rococo décor. The college buildings date from the Renaissance and were mostly built at the end of the 16th century. The Ursuline Church was finally built in 1677–1679.

The important secular buildings in the upper town include the Ratzéhof (built in the Renaissance style 1581–1585, now houses the Museum of Art and History), La Poya Castle (a Palladian villa surrounded by a private park , which was opened for the family in 1699–1701 Lanthen-Heid), the Gottrau house from the 18th century, the episcopal palace (1842–1845) and the former citizen's hospital from the late 17th century.

The Auquartier (French Quartier de l'Auge) forms the south-eastern continuation of the Burgquartier at a lower level. The Augustinian monastery and church are located here. The three-aisled church of Saint Mauritius with a polygonal choir goes back to the founding time of the monastery in the 13th century, but was changed several times in the 16th and 18th centuries; it has a rich interior, including a high altar with a carved retable (1602) and stone priests' seats (1594). Most of the convent buildings date from the 17th and 18th centuries and serve as the headquarters of the cantonal monument preservation service. The State Archives were housed here until 2005 and are now located in the Pérolles district. The Auquartier is characterized by various Gothic and late Gothic houses as well as squares decorated with fountains (Samaritan fountain, Anna fountain).

The Neustadt (Neuveville) with the Mariahilf Church (1749–1762, baroque interior) and numerous late Gothic houses is located in the valley floor of the Saane south of the Burgquartier .

On the other side of the Saane, in the Mattenquartier (Quartier de la Planche), the commandery and church of Saint John form the center. The church, consecrated in 1264, underwent major changes in 1885 and 1951, while the buildings of the former commandery date from the 16th and 17th centuries. Nearby is the barracks, a warehouse built between 1708–1709, which took over the function of a barracks in 1821 and was converted into it. Somewhat isolated and surrounded on three sides by the Saane is the Cistercian abbey of Magerau (Maigrauge), which was first mentioned in 1255. The church has largely retained its original form from the 13th century, the convent buildings were rebuilt after a fire in 1660–1666. The Montorge Monastery (founded in 1626) with a simple single-nave convent church from 1635, the Loreto Chapel (built in 1648 based on Santa Casa di Loreto ) and the Bürglentor (Porte de Bourguillon) are located on the promontory east of the Saane Dates from 14th to 15th centuries.

Outside the old town, the buildings of the Miséricorde University (1938–1941), the villa district with Art Nouveau buildings in the Gambach district and the concrete structure of the Christ the King's Church (1951–1953) on the Boulevard de Pérolles should be mentioned. There is also the headquarters of the Freiburger Kantonalbank, which was built 1979–1982 according to plans by Mario Botta . The Pérolles Castle, built for the Diesbach family from 1508 to 1522, and the private St. Bartholomew's Chapel in Gothic flamboyant style, which houses a collection of Renaissance stained glass by Lukas Schwarz from 1520-1523, are located near the former Cardinal brewery . In Bourguillon (Bürglen) is the single-nave church Notre-Dame, which was built 1464-1466. A war memorial for fallen alumni of the former boarding school Villa Saint-Jean on the Cimetière de St-Léonard commemorates the school days of the writer Antoine de Saint-Exupéry in the city.

Freiburg is also known for its numerous bridges that span the course of the Saane . The Bern Bridge, which connects the Auquartier with the bridgehead east of the Saane, is a covered wooden bridge that was given its shape in 1653. The Mittlere Brücke, a stone four-arch bridge from 1720, and from the Neustadt the Sankt Johannbrücke (1746, also with tuff stone blocks) lead to the Mattenquartier. In addition to these bridges in the valley, Freiburg has three high bridges. The Zähringer Bridge, which has been car-free since 2014, connects the Burgquartier directly with the Schönberg district; it was built in 1924 on the site of the suspension bridge from 1834, which until 1849 had been the longest of its kind in the world. The new Galtern Bridge replaced the first suspension bridge from 1840 in 1960, spans the Galterngraben and connects the districts of Schönberg and Bürglen (Bourguillon). The Pérolles Bridge, built in 1920, ultimately ensures a direct connection from the Pérolles district to Marly . A project for upgrading the old town is linked to the traffic relief in the city center through the Poya Bridge . The studio Montagnini Fusaro in Venice was awarded the contract.

coat of arms

The city coat of arms of Freiburg shows in blue a crenellated tower with a crenellated wall attached to the left, sloping in two steps with a half ring breaking out from below, all in silver. Although it has been in use since the 13th century, it was not until 1803 that the coat of arms was declared the city's official coat of arms after various modifications. The three towers of the city coat of arms embody the former rulers: city banners, castle banners, new town banners, hospital banners. The silver ring embodies the fourth banner , the Aubanner, which lies on the Saane.

Since the city of Freiburg was founded in 1157, this coat of arms has been changed several times. In the past, the coat of arms above the towers still had the Zähringer eagle, later it was divided into a four-part coat of arms (two city coats of arms, two canton coats of arms across the cross), which led to the official canton colors black and blue. The current canton colors black and white were only introduced with the collapse of the former city tensioners; until then, the city and cantonal coats of arms were merged.

The old canton colors can be clearly seen in the costume of the coat of arms of the Sense district as well as in the old regimental flags (e.g. Oberlandrist Regiment - Oberer Schrot Düdingen), which all had a black and blue flamed background behind the federal cross. The double coat of arms can still be seen on the old sign of the “Aigle Noir” inn (Alpenstrasse) in the center of Freiburg.

Sports

The most famous sports club in the city is the ice hockey club HC Friborg-Gottéron , which plays in the National League A and has been Swiss runner-up five times so far. The games will be played in the BCF Arena (capacity: 8,934 spectators).

The Friborg Olympic basketball club is another flagship club. In Switzerland, basketball is more of a marginal sport than ice hockey and football - especially in the German-speaking part. The audience march in the “Heimstadion” (St. Leonhard sports hall, until 2010 the gymnasium of the Heilig Kreuz college) of up to 3,500 spectators is only exceeded nationally at club level in football and ice hockey stadiums. In terms of sport, too (including 19-time Swiss champions, 9-time Swiss Cup winners and 5-time League Cup winners), the club is a national top.

The football club FC Friborg plays in the 1st league , the highest amateur class. There is also the floorball club Floorball Friborg , of the B National League plays.

Since 1933, the Murtenlauf (Course Morat-Friborg) has taken place on the first Sunday in October . This is one of the most famous and traditional fun runs in Switzerland, each with thousands of participants. The route is around 17 kilometers long, leads from Murten to Freiburg and is run to commemorate the Battle of Murten .

The sports infrastructure includes the St. Leonhard ice rink, the Stade Universitaire and various other sports fields, as well as a small indoor pool and the La Motta outdoor pool by architect Beda Hefti from 1923, the first outdoor pool in Switzerland that was neither a river nor a lake. In August 1928 it was the venue for the Swiss swimming championships.

Personalities

Town twinning

-

Rueil-Malmaison , since October 10, 1992.

Rueil-Malmaison , since October 10, 1992. -

Nova Friburgo

Nova Friburgo

In addition, Freiburg is one of the Zähringer cities .

literature

- Bernhard Altermatt: The institutional bilingualism of the city of Friborg-Freiburg: history, state and development tendencies . In: Bulletin suisse de linguistique appliquée. Neuchâtel 2005 (no. 82), 62–82 ( ISSN 1023-2044 ).

- Anton Bertschy, Michel Charrière: Friborg, a canton and its history. Friborg, un canton, une histoire . Freiburg 1991.

- Gaston Castella: Histoire du canton de Friborg depuis les origines jusqu'en 1857 . Freiburg 1922.

- Encyclopédie du canton de Friborg . Edited under the direction of Roland Ruffieux. 2 vols. Freiburg 1977.

- History of the Canton of Friborg / Histoire du Canton de Friborg . Edited under the direction of Roland Ruffieux. 2 vols. Freiburg 1981.

- François Guex, Hermann Schöpfer and Alain-Jacques Czouz-Tornare: Freiburg (municipality). In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- Léon Savary : Friborg . Payot, Lausanne, 1929. OCLC 12515493

- Hans-Joachim Schmidt (Ed.): City foundation and urban planning. Freiburg / Friborg in the Middle Ages . Munster 2010.

- Hermann Schöpfer: Art Guide City of Freiburg . Bern 1979.

- Marcel Strub: Les monuments d'art et d'histoire du canton de Friborg: la ville de Friborg . 3 vols. Basel 1956–1964.

- Silvia Zehnder-Jörg: The great Freiburg chronicle of Franz Rudella. ( Memento of February 14, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Edition based on the copy from the Freiburg State Archives. Phil. Diss., Freiburg (Switzerland) 2005. (The chronicle goes back to the year 1568, PDF; 5.6 MB.)

Web links

|

Further content in the sister projects of Wikipedia:

|

||

|

|

Commons | - Media content (category) |

|

|

Wiktionary | - Dictionary entries |

|

|

Wikisource | - Sources and full texts |

|

|

Wikivoyage | - Travel Guide |

- Website of the city of Freiburg (French / German)

- Website of «Freiburg Tourismus und Region» - the tourism office of the city of Freiburg

- Aerial photos of Freiburg

- Tour through Freiburg

Individual evidence

- ↑ FSO Generalized Boundaries 2020 . For later parish mergers, heights are summarized based on January 1, 2020. Accessed May 17, 2021

- ↑ Generalized limits 2020 . In the case of later community mergers, areas will be combined based on January 1, 2020. Accessed May 17, 2021

- ↑ Regional portraits 2021: key figures for all municipalities . In the case of later community mergers, population figures are summarized based on 2019. Accessed May 17, 2021

- ↑ Regional portraits 2021: key figures for all municipalities . For later community mergers, the percentage of foreigners summarized based on the 2019 status. Accessed May 17, 2021

- ↑ a b Lexicon of Swiss municipality names . Edited by the Center de Dialectologie at the University of Neuchâtel under the direction of Andres Kristol . Frauenfeld / Lausanne 2005, p. 369.

- ↑ The Basse-Ville

- ^ Freiburg / Friborg - a declaration of love , NZZ, May 6, 2004

- ↑ City history. Retrieved December 18, 2018 .

- ↑ Pierre Caille (Ed.): Annuaire statistique du canton de Friborg / Statistical Yearbook of the Canton of Friborg - 2018 . 47th edition. Direction de l'économie et de l'emploi / Economics Directorate, Freiburg December 2017, p. 14, 363 .

- ^ Rainer Schneuwly: Bilingual - How Freiburg and Biel deal with bilingualism . Hier und Jetzt Verlag, Baden 2019, ISBN 978-3-03919-460-5 , p. (Monograph) .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Georges Andrey, Jean-François Braillard: 500e anniversaire de l'entrée de Friborg dans la Confédération - 500 years of Freiburg in the Confederation . Ed .: Édouard Dousse. Friborg 1981, p. 25-31 .

- ↑ a b Nei, dasch zvüu, do me connais! , swissinfo, September 18, 2010

- ↑ a b c d e f Niklaus Meienberg : Reports . Ed .: Marianne Fehr, Erwin Künzli, Jürg Zimmerli. No. 8 . Limmat Verlag, Zurich 2000, ISBN 3-905753-08-1 , p. 168–175 (licensed edition Das Magazin / Swiss Library).

- ↑ a b c d Beat Hayoz, et al .: 40 × Seiselann; Sense district and Freiburg . Ed .: Beat Hayoz. Sensler Museum Tafers, Tafers 2015, ISBN 978-3-03305320-5 , p. 145 ff .

- ^ Victor Conzemius: Union de Friborg. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland . May 15, 2012 , accessed October 12, 2020 .

- ^ Jean-Christophe Emmenegger: Traces de l'âme polonaise à Friborg . In: Universitas . No. 4 . Friborg (Switzerland) June 2011, p. 51 f .

- ↑ Anne-Marie Steullet-Lambert: Les filles de l'international - Les années secrètes . Editions Cabédita, Bière 2017, ISBN 978-2-88295-785-6 .

- ↑ a b c d e Rudolf Ebneter, et al .: The College of St. Michael today - Le collège St-Michel aujourd'hui . Éditions La Sarine, Freiburg 2017, ISBN 978-2-88355-176-3 , p. 43-55 .

- ↑ Jean-Pierre Gross Rieder: La Broye fribourgeoise racontée par la carte postale 1890-1920 . Self-published (?) And Journal d'Yverdon SA (print), Estavayer-le-Lac 1984, p. 63, 88 (page 63: Institut Stavia (building 2), 88: Pensionat Montagny-la-Ville).

- ^ Villa Beausite (Association Fribourgeoise de Institutions pour Personnes Agées) . Retrieved December 9, 2018 (French).

- ^ Ernst Bollinger: La Liberté (newspaper). In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland . May 1, 2014 , accessed October 12, 2020 .

- ↑ Ernst Bollinger: Freiburger Nachrichten. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland . January 11, 2018 , accessed June 21, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Michel Charrière, et al .: Chronique Fribourgeoise 2017 . Société d'histoire du canton de Friborg / Cantonal and University Library of Friborg , Friborg October 2018, p. 77 (The numbers 403 and 41,200 include, in addition to the former Catholics, also a small proportion of former members of the Evangelical Reformed Church).

- ↑ Michel Charrière, et al .: Chronique Fribourgeoise 2016: L'église catholique entre réorganisation et éloignement des fidèles . Société d'histoire du canton de Friborg / Cantonal and University Library of Friborg , Friborg May 2017, p. 57 .

- ↑ Marianne Rolle: Jules Daler. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland . March 29, 2004 , accessed December 9, 2018 .

- ↑ Bernhard Flühmann: Tradition et Modernité - les 100 ans de l'Hôpital Daler / Tradition and Modernity - 100 years of Daler Spital . Friborg 2017, ISBN 978-2-8399-2060-5 , pp. 7-11 .

- ^ Freiburg / Friborg (capital of the canton of Freiburg / Friborg, CH) Jewish history / synagogue , at www.alemannia-judaica.de, accessed on May 7, 2017.

- ↑ Results | Etat de Friborg. Retrieved March 8, 2021 (French).

- ↑ Election of the General Council on February 28, 2016. (PDF) State of Freiburg, February 29, 2016, accessed on April 9, 2016 .

- ^ Election du conseil général. (PDF) City of Freiburg, March 21, 2011, accessed on April 9, 2016 .

- ↑ http://www.ville-fribourg.ch/vfr/files/pdf32/Resultat_elec_compl.pdf , According to Friborg law, a supplementary election must take place if more people are elected on a list than are candidates, this was the case in 2011 for the list "Libre et indépendent", which won two seats with one candidate, in the supplementary election on May 15, 2011, the Green candidate was elected.

- ↑ Election du Conseil national du 20 octobre 2019: Résultat de la commune Ville de Friborg. Chancellerie d'Etat du canton de Friborg, October 20, 2019, accessed on October 23, 2019 (French).

- ↑ Grossfreiburg constituent assembly. Retrieved December 22, 2019.

- ^ Freiburg / Friborg - a declaration of love , NZZ, May 6, 2004

- ^ Nicole Zimmermann: Les EEF et le développement économique - Un siècle de collaboration . Ed .: Gaston Gaudard. 1st edition. Buchheim Éditions, Friborg 1990, p. 16-27 .

- ↑ Anne Wicht-PIERART: Sibra. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland . October 4, 2010 , accessed December 18, 2018 .

- ^ Jean-Pierre Dorand: Nordmann. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland . February 1, 2011 , accessed November 6, 2019 .

- ^ Freiburg's contaminated sites - government proposes a variant for the rehabilitation of the La Pila landfill. In: srf.ch . February 15, 2019, accessed August 20, 2019 .

- ^ La Pila landfill. Information from the canton of Friborg, accessed on November 18, 2020 .

- ↑ BLUEFACTORY Friborg – Freiburg SA. Retrieved December 8, 2018 .

- ↑ Verena Villiger (ed.): Museum for Art and History Freiburg - the collection. (Swiss Art Guide, No. 832/833, Series 84). Ed. Society for Swiss Art History GSK. Bern 2008, ISBN 978-3-85782-832-4 .

- ^ Museum of Art and History MAHF , at www.fr.ch, accessed on December 18, 2018

- ↑ Portrait on the festival website, accessed on July 25, 2012.

- ↑ Rédaction La Liberté : Facebook a eu la peau du Goulag Festival - Créé en 2011 à la Pisciculture, à Friborg, le Goulag Festival change de nom après une mobilization sur les réseaux sociaux contre l'utilisation de ce nom. Une soixantaine d'intellectuels ont souscrit à l'appel d'une socialiste genevoise. In: La Liberté. December 28, 2017, accessed November 6, 2019 (French).

- ^ Theater in Freiburg. Retrieved December 8, 2018 .

- ↑ La dissolution de la CUTAF (Communauté urbaine des transports de l'agglomération fribourgeoise) . Message du Conseil communal au Conseil général, No. 47 May 12, 2009

- ↑ Freiburg www.velopass.ch ( Memento of 10 July 2010 at the Internet Archive )

- ↑ regulators Saner: PubliBike: What will be discussed in Bern, is in Freiburg reality. In: bernerzeitung.ch . February 3, 2020, accessed April 6, 2020 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Adriana Spallanzani et al. (traduit par Jean-Jacques Langendorf): Guide culturel de la Suisse . Ed .: Niklaus Flüeler. Ex Libris, Zurich 1982, p. 145-151 .

- ^ Ernst Theodor Gaupp : German city rights in the Middle Ages, with legal historical explanations . Second volume, Breslau 1852, pp. 58-107, online.

- ↑ a b c d e f Andreas Z'Graggen, Barbara Franzen, Ruedi Arnold: Aristocracy in Switzerland - How ruling families shaped our country for centuries . 1st edition. NZZ Libro / Schwabe, Zurich 2018, ISBN 978-3-03810-334-9 , p. 110-121 .

- ^ Article «Freiburg», in: Historisch-Biographisches Lexikon der Schweiz, Neuenburg 1926, p. 256.

- ↑ Kathrin Utz Tremp: Perroman Society. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland . October 13, 2011 , accessed June 21, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Pierre Felder, Helmut Meyer, Claudius Sieber-Lehmann et al .: Switzerland and its history . 1st edition. Lehrmittelverlag des Kantons Zürich / Intercantonale Lehrmittelzentrale, Zürich 1998, ISBN 3-906719-96-0 , p. 113, 128, 173 .

- ↑ Hans Georg Wehrens: The dance of death in the Alemannic language area. «I have to do it - and don't know what» . Schnell & Steiner, Regensburg 2012, ISBN 978-3-7954-2563-0 . P. 182 ff. Verena Villiger: Pierre Wuilleret, monograph, catalog raisonné and exhibition catalog. Bern 1993, pp. 72-91.

- ^ Christian Schütt (Ed.): Chronicle of Switzerland; Freiburg becomes a university city . Chronik Verlag (Ex Libris Verlag), Dortmund (Zurich) 1987, ISBN 3-611-00031-0 , p. 456 .

- ^ Christian Schütt (Ed.): Chronicle of Switzerland; Jesuits are allowed to return . Chronik Verlag (Ex Libris Verlag), Dortmund (Zurich) 1987, ISBN 3-611-00031-0 , p. 354 .

- ^ Fabien Python: D'art et d'histoire - Tribulations d'un musée XVIIIe – XXIe siècle . 1st edition. Société d'histoire du Canton de Friborg, Friborg 2018, ISBN 978-2-9701205-2-0 , p. 21 ff .

- ^ Daniel Bitterli (ed.): Franz Peter König. A Swiss in the Thirty Years War. Sources . Collaboration: Manuel Bigler, Wendelin Brühwiler, Nicolas Maternini and Lucia de Masi (= Archives de la Société d'histoire du canton de Friborg . Band 1 ). 2006, ISBN 978-2-9700548-0-1 , pp. 12-13 .

- ↑ Christian Schütt (Ed.): Chronicle of Switzerland; Criminal proceedings involving torture . Chronik Verlag (Ex Libris Verlag), Dortmund (Zurich) 1987, ISBN 3-611-00031-0 , p. 337 .

- ↑ Pierre Rime: Dénonciations et en République délations fribougeoise . Editions Cabédita, Bière 2019, ISBN 978-2-88295-850-1 .

- ↑ Christian Schütt (Ed.): Chronicle of Switzerland; New home in Brazil . Chronik Verlag (Ex Libris Verlag), Dortmund (Zurich) 1987, ISBN 3-611-00031-0 , p. 356 .

- ↑ a b c Joseph Jung : The Laboratory of Progress - Switzerland in the 19th Century . NZZ Libro, Zurich 2019, ISBN 978-3-03810-435-3 , p. 219 .

- ↑ La saga de l'histoire des suisses au Brésil. Association Friborg - Nova Friborg, Freiburg, accessed on December 14, 2018 (French).

- ↑ Christophe Mauron: La reencarnación de Helvetia - Historia de los suizos en Baradero (1856-1956) . Ed .: Néstor Braillard, Martin Nicoulin, Gérald Arlettaz. Sociedad Suiza de Baradero / Association Baradero-Friborg, Baradero (Argentine) 2006, ISBN 950-02-9842-2 .

- ^ Roger Pasquier: Marie Pittet l'émigrée - Des Fribourgeois en Patagonie chilienne . Éditions La Sarine, Friborg 2008, ISBN 978-2-88355-115-2 .

- ↑ Alain-Jacques Tornare Czouz-: Freiburg (municipality): 3. 19th and 20th centuries, 3.2 economy and society. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland . February 4, 2010 , accessed October 12, 2020 .

- ↑ Christian Schütt (Ed.): Chronicle of Switzerland; Riots in Freiburg . Chronik Verlag (Ex Libris Verlag), Dortmund (Zurich) 1987, ISBN 3-611-00031-0 , p. 410 .

- ↑ a b Thierry Jacolet: Un siècle d'action humanitaire [commentaire de l'auteur: sur la Croix-Rouge fribourgeoise] . Éditions La Sarine, Friborg 2009, ISBN 978-2-88355-126-8 , p. 26-32, 98 .

- ^ Alain-Jacques Tornare: 150 e anniversaire du passage des Bourbakis à Friborg . In: 1700. Bulletin d'information de la Ville de Friborg = bulletin of the city of Freiburg . No. 371 , February 2021, p. 8–9 (French).