Boeing 747: Difference between revisions

Archtransit (talk | contribs) →747-100SR: fix ref |

Archtransit (talk | contribs) →747-100: fix ref |

||

| Line 121: | Line 121: | ||

[[Image:Pan Am 747 LAX.jpg|thumb|right|[[Pan Am]] 747-100 illustrating the original size of the upper deck design and window layout]] |

[[Image:Pan Am 747 LAX.jpg|thumb|right|[[Pan Am]] 747-100 illustrating the original size of the upper deck design and window layout]] |

||

The first 747-100s off the line were built with six upper-deck windows (three per side) to accommodate upstairs lounge areas. Later, as airlines began to use the upper-deck for premium passenger seating instead of lounge space, Boeing offered a ten window upper deck as an option. Some -100s were even retrofitted with the new configuration.<ref>[http://www.aircraftspotting.net/aircraft/boeing_747.html Boeing 747], |

The first 747-100s off the line were built with six upper-deck windows (three per side) to accommodate upstairs lounge areas. Later, as airlines began to use the upper-deck for premium passenger seating instead of lounge space, Boeing offered a ten window upper deck as an option. Some -100s were even retrofitted with the new configuration.<ref>[http://www.aircraftspotting.net/aircraft/boeing_747.html Boeing 747], Aircraft Spotting. Retrieved: [[7 December]] [[2007]].</ref> |

||

A '''747-100B''' version, which has a stronger airframe and undercarriage design as well as an increased maximum takeoff weight (MTOW) to {{lb to kg|750000|precision=-3}} was offered. The 747-100B was only delivered to [[Iran Air]] and Saudia (now Saudi Arabian Airlines).<ref>[http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9B05E3DB1039F932A05750C0A967948260&n=Top/Reference/Times%20Topics/Subjects/S/Sales Saudia Orders 4 Boeing 747's] Retrieved: [[12 December]] [[2007]].</ref> Optional engine models were offered by [[Rolls-Royce plc|Rolls-Royce]] ([[Rolls-Royce RB211#RB211-524 series|RB211]]) and [[GE Aviation|GE]] ([[General Electric CF6|CF6]]), but only the Rolls-Royce option was ordered by [[Saudi Arabian Airlines|Saudia]].<ref>Norris 1997, p. 53.</ref> |

A '''747-100B''' version, which has a stronger airframe and undercarriage design as well as an increased maximum takeoff weight (MTOW) to {{lb to kg|750000|precision=-3}} was offered. The 747-100B was only delivered to [[Iran Air]] and Saudia (now Saudi Arabian Airlines).<ref>[http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9B05E3DB1039F932A05750C0A967948260&n=Top/Reference/Times%20Topics/Subjects/S/Sales Saudia Orders 4 Boeing 747's] Retrieved: [[12 December]] [[2007]].</ref> Optional engine models were offered by [[Rolls-Royce plc|Rolls-Royce]] ([[Rolls-Royce RB211#RB211-524 series|RB211]]) and [[GE Aviation|GE]] ([[General Electric CF6|CF6]]), but only the Rolls-Royce option was ordered by [[Saudi Arabian Airlines|Saudia]].<ref>Norris 1997, p. 53.</ref> |

||

No freighter version of this model was developed by Boeing. However, 747-100s have been converted to freighters.<ref>[http://rgl.faa.gov/Regulatory_and_Guidance_Library/rgEX.nsf/0/a590a0405960013a86256d4400727f45/$FILE/1870D.pdf FAA Regulatory and Guidance Library] Retrieved: [[12 December]] [[2007]]. See reference to Supplementary Type Certificates for freighter conversion.</ref> |

No freighter version of this model was developed by Boeing. However, 747-100s have been converted to freighters.<ref>[http://rgl.faa.gov/Regulatory_and_Guidance_Library/rgEX.nsf/0/a590a0405960013a86256d4400727f45/$FILE/1870D.pdf FAA Regulatory and Guidance Library], FAA. Retrieved: [[12 December]] [[2007]]. See reference to Supplementary Type Certificates for freighter conversion.</ref> |

||

A total of 250 -100s (all versions, including the 747SP) were produced, the last one being delivered in 1986.<ref>[http://www.boeing.com/news/feature/sevenseries/747.html Fast Facts: 747], The Boeing Company. Retrieved 16 December 2007</ref> Of these, 167 were 747-100, 45 were SP, 29 were SR, and 9 were 100B.<ref>[http://www.boeing.com/commercial/747family/pf/pf_classics.html Boeing Commercial Airplanes - 747 Classics Technical Specs] Retrieved: [[12 December]] [[2007]].</ref> |

A total of 250 -100s (all versions, including the 747SP) were produced, the last one being delivered in 1986.<ref>[http://www.boeing.com/news/feature/sevenseries/747.html Fast Facts: 747], The Boeing Company. Retrieved 16 December 2007</ref> Of these, 167 were 747-100, 45 were SP, 29 were SR, and 9 were 100B.<ref>[http://www.boeing.com/commercial/747family/pf/pf_classics.html Boeing Commercial Airplanes - 747 Classics Technical Specs], The Boeing Company. Retrieved: [[12 December]] [[2007]].</ref> |

||

====747-100SR==== |

====747-100SR==== |

||

Revision as of 23:14, 17 December 2007

Template:Infobox Aircraft

Template:Edit-first-section

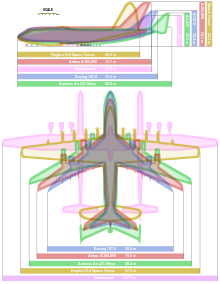

The Boeing 747, sometimes nicknamed the "Jumbo Jet",[1][2] is the first widebody commercial airliner ever produced. The Boeing 747, manufactured by Boeing in the United States, is among the world's most recognizable aircraft.[3] The original version of the 747 was two and a half times the size of the Boeing 707,[4] one of the aircraft that was credited with revolutionizing intercontinental travel a decade earlier.[5] First flown commercially in 1970, it held the passenger capacity record for 37 years.

The four-engine 747, produced by Boeing's Commercial Airplane unit, uses a double deck configuration for part of its length. The hump created by the upper deck has made the 747 a highly recognizable icon of air travel. The 747 is available in passenger, freighter and other versions.

The 747-400, the latest version in service, flies at high-subsonic speeds of Mach 0.85 (567 mph or 913 km/h), and features an intercontinental range of 7,260 nautical miles (8,350 mi, 13,450 km).[6] The 747-400 passenger version can accommodate 416 passengers in a typical three-class layout or 524 passengers a typical two-class layout.

The 747 was expected to become obsolete after sales of 400 units due to the development of supersonic airliners,[7] but it has outlived many of its critics' expectations and production passed the 1,000 mark in 1993. As of June 2007, 1,387 aircraft had been built, with 120 more in various configurations on order.[8] The latest development of the aircraft, the 747-8, is planned to enter service in 2009.[9]

Development

Background and design phase

The 747 was conceived while air travel was increasing in the 1960s.[10] The era of commercial jet transportation, led by the enormous popularity of the Boeing 707 and Douglas DC-8, had revolutionized long-distance travel.[11] In 1965, Boeing lost the Heavy Logistics System (CX-HLS) competition for the development of a large military transport, which would eventually result in the Lockheed C-5 Galaxy. Boeing's design proposal was instead considered internally as a basis for a commercial airliner.[12] Ultimately, the Boeing proposals that were selected for the high winged CX-HLS and the low winged 747 were completely different designs although influence from the earlier military design in designing the 747 have been alleged.[13] The development team avoided using hardware from the CX-HLS proposal, other than the high-bypass turbofan engine technology.[14][15] Even before it lost the CX-HLS contract to Lockheed in September 1965, Boeing came under pressure from Juan Trippe, president of Pan Am, one of its most important airline customers, to build a large passenger airplane that would be over twice the size of the 707. During this time, airport congestion, constricted by the size of aircraft used and the increasing passenger traffic, became a problem which Trippe thought could be addressed by a large new aircraft.[16]

In 1965, Joseph Sutter was transferred from Boeing's 737 development team to manage the studies for a new airliner, already assigned its model number 747.[17] Development of the aircraft was considered to be both a technical and a financial challenge: it was said that management "bet the company" when developing the 747.[17][18] The original design was a full-length double-deck fuselage seating eight across (3–2–3) on the lower deck and seven across (2–3–2) on the upper deck.[19] However, concern over evacuation routes and limited cargo-carrying capability caused this idea to be scrapped in early 1966 in favor of wider single deck, becoming the first wide-body airliner.[18] Boeing agreed to deliver the first 747 to Pan Am by the end of 1969. The delivery date left 28 months to design the aircraft, which was two thirds the normal time allotted.[20]

In April 1966, Pan Am ordered twenty-five of the initial 100 series for US$525 million. During the ceremonial 747 contract-signing banquet in Seattle, concurrent to Boeing's 50th Anniversary, Juan Trippe predicted the 747 as "...a great Weapon for peace, competing with intercontinental missiles for mankind's destiny.", according to an interview with Malcolm T. Stamper.[3] As launch customer,[21][22] and because of its early involvement before placing a formal order, Pan Am was able to influence the design and development of the 747 to an extent not seen by a single airline before or since.[23]

One of the principal technologies that enabled an airplane as large as the 747 to be conceived was the high-bypass turbofan engine.[24] This promised to deliver double the power of the earlier turbojets while consuming a third less fuel. General Electric had pioneered the concept but were fully committed to developing the engine for the C-5 Galaxy and did not enter the commercial market until later.[25][26] Pratt & Whitney was also working on the same principle, and, by late 1966, Boeing, Pan-Am and Pratt & Whitney agreed that they would develop a new engine, designated JT9D, to power the 747.[26] Four of these engines were to be mounted in pods below the 747's wings.

Safety was a high priority on a large passenger airplane such as the 747. It was designed with a new methodology called fault tree analysis, where the effects of a failure of a single part could be studied to determine its impact on other systems.[18] For safety and flyability concerns, the 747's design included structural redundancy, redundant hydraulic systems, quadruple main landing gear and split control surfaces.[27]

At the time, it was widely thought that the 747 would eventually be superseded by supersonic transport (SST) aircraft,[28] so Boeing designed it such that it could easily be adapted to carry freight, so that it could remain in production if and when sales of the passenger version dried up. The cockpit was therefore placed on a shortened upper deck so that a nose cone loading door could be included, thus creating the 747's distinctive "bulge".[29] However, supersonic transports, such as the Concorde, Tupolev Tu-144 and the canceled Boeing 2707, were not widely adopted.[30] SSTs were less fuel-efficient at a time when fuel prices were soaring, very noisy during takeoff and landing, and their ability to operate at supersonic speeds over land was limited by regulations concerning their sonic booms.[31]

Production facilities

Boeing did not have a facility large enough to assemble the giant airliner, so it had to build a new one. The company looked at locations in about 50 cities.[32] The company eventually decided to build the new plant some 30 miles (50 km) north of Seattle on a site adjoining a military base at Paine Field near Everett, Washington.[33] In June 1966, Boeing bought the 780 acre (316 hectare) site.[21]

While developing the 747 had been a major challenge, constructing the plant in which to build it was also a huge undertaking. Boeing president William M. Allen asked Malcolm T. Stamper, then head of the company's turbine division, to lead construction of the Everett factory and start up production of the 747.[34]

To level the site, over four million cubic yards of earth had to be moved.[35] Such was the shortage of time that the 747's full-scale mock-up had to be built before the factory roof had been constructed above it.[36] The plant is the largest building by volume ever built.[15][33]

Boeing had promised to deliver the 747 to Pan Am by 1970, which gave it less than four years to develop, build and test the aircraft. Work progressed at such a breakneck pace that those who worked on the development of the 747 were given the nickname "The Incredibles".[15]

Development and testing

Before the first 747 was even fully assembled, testing began on numerous components and systems. One of the most anxiously awaited tests was the emergency evacuation, to see how long it took for 560 volunteers to exit from a cabin mock-up using the plane's emergency chutes. The first full-scale test took two and a half minutes instead of the maximum 90 seconds mandated by the Federal Aviation Administration, and resulted in several injuries to the volunteers. Subsequent tests achieved the 90-second limit, albeit at the cost of more injuries. Most problematic was evacuation from the airplane's upper deck: instead of the usual slide there was an escape harness attached to a reel.[37]

Boeing built an unusual training device known as "Waddell's Wagon" (named after the 747 test pilot, Jack Waddell), which consisted of a mock-up cockpit mounted on the roof of a truck, for training pilots how to taxi the plane from the high upper deck position before the 747's first flight.[15]

On 30 September 1968, the first 747 was rolled out of the Everett assembly building in front of the world's press and representatives of the 26 airlines that had ordered the plane.[38]

Over the following months preparations were made for the first flight, which took place successfully on 9 February 1969, with test pilots Jack Waddell and Brien Wygle at the controls[39][40] and Jess Wallick at the flight engineer's station. In spite of a minor problem with one of the flaps, the flight confirmed that the 747 handled extremely well; the plane was found to be largely immune to "dutch roll", a phenomenon that had been a major hazard to the early swept-wing jets.[41]

During later stages of the flight test program, flutter testing showed that the wings suffered oscillation in certain conditions. These difficulties were partly solved by reducing the stiffness of some wing components. However, a particularly severe high-speed flutter problem was only solved by inserting depleted uranium counterweights as ballast in the outboard engine nacelles of the early 747s.[42] This measure caused some anxiety when several of these aircraft were lost, such as the 1991 crash of China Airlines Flight 358 at Wanli and 1992 crash of El Al Flight 1862 at Amsterdam.[43][44]

The flight test program was considerably hampered by problems with the plane's JT9D engines: these included engine stalls caused by rapid movements of the throttles and distortion of the turbine casings after a short period of service.[45] The problems caused 747 deliveries to be delayed several months, resulting in up to 20 planes at one time being stranded at the Everett plant awaiting engines.[46] The program was further set back when the third of five test airplanes suffered serious damage while attempting to land at Renton Municipal Airport where Boeing's Renton plant is located. The test aircraft was being taken to have its test equipment removed and a cabin installed when pilot Ralph C. Cokely undershot the short runway and sheared off the 747's landing gear.[47] However, these difficulties did not prevent Boeing taking one of the test aircraft to the 28th Paris Air Show in mid-1969 where it was displayed to the general public for the first time.[48] The 747 achieved its FAA airworthiness certificate in December 1969, paving the way for its introduction into service.[49]

The huge cost of developing the 747 and building the Everett factory meant that Boeing had to borrow heavily from a banking syndicate to fund the project. During the final months before delivery of the first airplane the company had to repeatedly request additional funding from the syndicate to enable it to complete the project; had this been refused the survival of the Boeing itself would have been threatened.[50][22] However, the gamble paid off and Boeing enjoyed a monopoly in the very large passenger aircraft segment for many years.[51]

Entry into service

The prototype Boeing 747 was named City of Everett.[52] On 15 January 1970, American First Lady Patricia Nixon christened the first Pan Am 747 at Dulles International Airport (now called Washington Dulles International Airport) in the presence of Pan Am chairman Najeeb Halaby. Instead of a bottle of champagne, red, white and blue water was sprayed on the plane.

The 747-100 entered service on 22 January 1970 with launch customer Pan American World Airways on the New York-London route.[53] The flight was supposed to occur on January 21, but engine overheating made the original airplane unusable and it had to be substituted, creating a more than six-hour delay to the next day.[53]

As the 747 was introduced into service in 1970, many other airlines were forced to compete with Pan Am and rushed to bring their own 747s into service.[54][55] In popular culture, the 747 appeared in various film productions including as the Airport series of disaster films, Air Force One and Executive Decision.[56][57]

In the early 1970's, McDonnell Douglas and Lockheed were working on wide-body three engine "tri-jets", which were smaller than the 747. Some airlines believed the 747 would prove too large a passenger capacity for an average flight, operating tri-jets instead. There were also concerns that the 747 would not be compatible with existing airport infrastructure, an issue which has resurfaced with the Airbus A380, due to its double-deck feature.[58]

Economic problems in the United States and other countries after the 1973 oil crisis led to a cyclic low in passenger traffic resulting in several airlines eliminating the 747 from their fleet.[59] While the 747 had the lowest potential operating costs per seat, this was only achievable when aircraft were fully loaded; costs per seat increased rapidly as occupancy declined.[60] American Airlines replaced coach seats on its 747s with piano bars in an attempt to attract more customers. Eventually, it relegated its 747s to cargo service[61] and then exchanged them with Pan Am for smaller aircraft.[61] Continental Airlines also removed its 747s from service after several years. The advent of smaller wide bodies, starting with the trijet DC-10 and L-1011, and followed by the twinjet 767 and A300, took away much of the 747's original market, especially as international flights from smaller cities which bypassed traditional hub airports became more common.[62] Half of the 747 sales prior to the introduction of the Boeing 777 were because of airline requirements for long range capability, not payload capacity, according to Boeing's estimation.[63] However, many international carriers continued to use the 747 on Pacific routes.[64] In Japan, 747s on domestic routes are configured to carry close to the maximum passenger capacity.[65]

From the initial 747-100 model, Boeing developed the higher gross weight -100B variant and higher passenger capacity -100SR (Short Range) variant.[66] (Increased maximum takeoff weight (MTOW) can allow an aircraft to carry more fuel and have longer range.[67]) The -200 model followed, entering service in 1971. It featured more powerful engines and higher gross weight. Passenger, freighter and combination passenger/freighter versions were produced.[66] The shortened 747SP (Special Performance) with a longer range was also developed in the mid-1970s.[68]

Further developments

The 747 line was further developed with the launching of the 747-300 in 1980. The -300 was a result of Boeing studies to increase the seating capacity of the 747. Various solutions such as fuselage plugs and extending the upper deck on the entire length of the fuselage were not adopted. The early designation of the -300 was the 747SUD for "stretched upper deck" and 747-200 SUD,[69] followed by 747EUD, before the 747-300 designation was used.[70] The -300 model was introduced into airliner service in 1983. It included a Stretched Upper Deck (SUD), increased cruise speed and increased seating capacity. Passenger, short range and combination freighter/passenger versions were produced.[66]

In 1985, development of the longer range 747-400 was begun.[71] The new variant had a new cockpit allowing for a cockpit crew of two, instead of three.[72] Development cost soared and production delays occurred as new technologies were incorporated at the request of airlines. Insufficient workforce experience and reliance on overtime contributed to early production problems on the 747-400.[73]

Since the arrival of the 747-400 in 1989, several stretching schemes for the 747 have been proposed. Boeing announced the larger 747-500X/-600X designs in 1996.[74] The new variants would have been cost over $5 billion to develop,[74] and interest was not sufficient to launch.[75] Boeing offered the more modest 747X and 747X Stretch derivatives as alternatives in 2000 to Airbus's A3XX study. However the 747X family was unable attract enough interest to enter production. Boeing switched from the 747X studies to pursue the Sonic Cruiser in 2001,[76] and then onto the 787 after the Sonic Cruiser program was put on hold.[77] Some of the ideas developed for the 747X were, however, used on the 747-400ER.[78] Boeing had consecutively proposed several variants that were never launched leading to skepticism among some industry observers[79] when in early 2004, Boeing rolled out tentative plans for the 747 Advanced. Similar in nature to the 747-X plans, the stretched 747 Advanced used advanced technology from the 787 to modernize the design and its systems.

On 14 November 2005, Boeing announced it was launching the 747 Advanced as the Boeing 747-8.[80] The 747-8 order book benefited from long delays in production of the Airbus A380 when two Airbus customers signed additional 747-8 orders,[81][82] two customers cancelled their A380 orders and several launch customers deferred delivery or considered switching their order to the 747-8 and 777F aircraft.[83][84]

The 747 remained the largest passenger airliner in service until the Airbus A380 began airline service in 2007.[85] In 1991, a record-breaking 1,087 passengers were airlifted aboard a 747 to Israel as part of Operation Solomon.[86] The 747 was the heaviest airliner in regular service until the use of the Antonov An-124 Ruslan in 1982, the 747-400ER model regaining the title in 2000. The Antonov An-225 cargo transport remains the world's largest aircraft by a number of measures (including the most accepted measure of maximum gross takeoff weight and length), and is in service, while the Hughes H-4 Hercules is the largest only by wingspan, but only flew once.[87] Only two An-225 aircraft have been produced with only one still flying, while the 747 and A380 are made for serial mass production.

747 aircraft have been converted for special uses. A 747-100 is owned by General Electric and used as a testbed for their engines[88][89]such as General Electric GEnx.[90] A firefighting prototype has been constructed by Evergreen International.[91] Eventually, the 747 may be replaced by an all new design dubbed "Y3".

Design

The Boeing 747 is a large, wide body (two aisles) airliner with four wing-mounted engines. The wings have a high sweep angle of 37.5 degrees for a fast, efficient cruise[92] of Mach 0.84 to 0.855 depending on variant as well as allowing the 747 to use existing hangars.[18][93] Seating capacity is over 366 with a 3-4-3 seat arrangement in economy class and 2-3-2 arrangement in first class on the main deck. The upper deck has a 3-3 seat arrangement in economy class and a 2-2 arrangement in first class.[94]

The cockpit is raised above the main deck creating a hump. The raised cockpit was to allow front loading of cargo on freight variants.[92] The upper deck behind the cockpit provided space for a lounge or extra seating. The "stretched upper deck" became available as an option on the 747-100B variant and later as standard on the 747-300.

The 747's maximum takeoff weight ranges from 735,000 pounds (333,400 kg) for the -100 to 970,000 lb (439,985 kg) for the -8. Its range has increased from 5,300 nautical miles (6,100 mi, 9,800 km) on the -100 to 8,000 nmi (9,200 mi, 14,815 km) on the -8I.[95][96]

The 747 has multiple structural redundancy with four redundant hydraulic systems, and four main landing gear with 16 wheels which provide a good spread of support on the ground and safety in the event of tire blow-outs. The redundant main gear allows for landing on two opposing landing gear if the others do not function properly.[27] In addition, the 747 has split control surfaces and sophisticated triple-slotted flaps that minimizes landing speeds allowing it to use standard-length runways.[97]

For transportation of spare engines, early 747s include the ability to attach a non-functioning fifth-pod engine under the port wing of the aircraft, between the nearest functioning engine and the fuselage.[98][99]

Variants

The 747-100 was the original and launched in 1966. The 747-200 followed soon after with an order in 1968. The 747-300 was launched in 1980, and was followed in 1985 by the 747-400. Lastly, the 747-8 was announced in 2005. Several versions of each variant have been produced, and many of the early variants were in production at the same time, especially in the 1980s.

747-100

The first 747-100s off the line were built with six upper-deck windows (three per side) to accommodate upstairs lounge areas. Later, as airlines began to use the upper-deck for premium passenger seating instead of lounge space, Boeing offered a ten window upper deck as an option. Some -100s were even retrofitted with the new configuration.[100]

A 747-100B version, which has a stronger airframe and undercarriage design as well as an increased maximum takeoff weight (MTOW) to Template:Lb to kg was offered. The 747-100B was only delivered to Iran Air and Saudia (now Saudi Arabian Airlines).[101] Optional engine models were offered by Rolls-Royce (RB211) and GE (CF6), but only the Rolls-Royce option was ordered by Saudia.[102]

No freighter version of this model was developed by Boeing. However, 747-100s have been converted to freighters.[103]

A total of 250 -100s (all versions, including the 747SP) were produced, the last one being delivered in 1986.[104] Of these, 167 were 747-100, 45 were SP, 29 were SR, and 9 were 100B.[105]

747-100SR

With requests from Japanese airlines, Boeing developed the 747-100SR as a 'Short Range' variant of the 747-100. The SR has a lower fuel capacity, but can carry more passengers, up to 498 passengers in early versions and more than 550 passengers in later models,[66] because of increased economy class seating. The 747SR has a modified body structure to accommodate the added stress accumulated from a greater number of takeoffs and landings.[106] The -100SR entered service with Japan Airlines (then Japan Air Lines) on 7 October 1973.[107] Later, short range versions were developed also of the -100B and the -300. The SR airplanes are primarily used on domestic flights in Japan.[108]

Two 747-100B/SRs were delivered to Japan Airlines (JAL) with a stretched upper deck to accommodate more passengers. This is known as the "SUD" (stretched upper deck) modification.[109][110]

All Nippon Airways (ANA) operated 747SR on domestic Japanese routes with 455-456 seats but retired the last aircraft on 10 March 2006.[111] JAL operated the 747-100B/SR/SUD variant with 563 seats on domestic routes which were retired in the third quarter of 2006. JAL and JALways have operated the -300SRs on domestic leisure routes and to other parts of Asia.

747-200

The 747-200 has more powerful engines, higher takeoff weights (MTOW), and range than the -100. A few early build -200s retained the three window configuration of the -100 on the upper deck, but most were built with a ten window per side configuration.[112]

Several versions in addition to the -200 were produced. The 747-200B is an improved version of the 747-200, with increased fuel capacity and more powerful engines which first entered into service in February 1971.[113] The -200B aircraft has a full load range of about 6,857 nmi (12,700 km). The 747-200F was the freighter version of the -200 model. It could be fitted with or without a side cargo door.[113] It has a capacity of 105 tons (95.3 tonnes) and a MTOW of up to 833,000 lb (378,000 kg). It entered first service in 1972 with Lufthansa.[114] The 747-200C Convertible is a version that can be converted between a passenger and a freighter as well as mixed configurations.[66] The seats are removable and the model has a nose cargo door.[113] The -200C could be fitted with an optional side cargo door on the main deck.[115]

The 747-200M is a combination version that has a side cargo door on the main deck and can carry freight in the rear section of the main deck. A removable partition on the main deck separates the cargo area at the rear from the passengers at the front. This model can carry up to 238 passengers in a 3-class configuration, if cargo is carried on the main deck. The model is also known as the 747-200 Combi.[113] As on the -100, a stretched upper deck (SUD) modification was later offered. A total of 10 conversion were operated by KLM.[113] UTA French Airlines also had two aircraft converted.[116][117]

A total of 393 of the -200 versions were produced when production ended in 1991.[118] Of these, 225 were 747-200, 73 were F, 13 were C, 78 were M, and 4 were military.[119]

747SP

The 747SP is 48 feet and four inches shorter than the 747-100. Apart from the planned 747-8, the SP is the only 747 with a modified length fuselage. Fuselage sections were eliminated fore and aft of the wing in addition to a redesigned center section. Single-slotted flaps replaced the complex triple-slotted Fowler flaps of the 100 series.[120] The under-wing "canoes" which housed the flap mechanisms on full-size 747s were eliminated entirely on the SP.[121] The 747SP, compared to earlier variants, had a tapering of the aft upper fuselage into the empenage, a double hinged rudder, and longer vertical and horizontal stabilizers.[122]

The Boeing 747SP was granted a supplemental type certificate on 4 February 1976 and entered service with Pan American World Airways, the launch customer, that same year.[121]

A total of 45 747SP were built.[123] The 44th 747SP was delivered on August 30, 1982. Boeing re-opened the 747SP production line to build one last 747SP five years later in 1987 for an order by the United Arab Emirates government.[121]

As of August 2007, 17 Boeing 747SP aircraft were in service with Iran Air (3), Saudi Arabian Airlines (1), Syrian Arab Airlines (2) and as executive versions. NASA's Dryden Flight Research Center has one modified for the SOFIA experiment.[124]

747-300

The differences between the -300 and the -200 include a lengthened upper deck with two new emergency exit doors and an optional flight crew rest area immediately aft of the flight deck. Compared to the -200, the upper deck is 23 feet 4 inches longer (7.11 m) that the -200.[125] A new straight stairway to the upper deck instead of a spiral staircase is another difference between the -300 and earlier variants.[66] This created more room both below and above for more seats. Some airlines, such as Japan Airlines, placed economy passengers in the upper deck, while many other airlines used the upper deck for business class.[126][127] With minor aerodynamic changes, Boeing increased the cruise speed of the -300 to Mach 0.85 from Mach 0.84 on the -100/-200.[125] The -300 features the same takeoff weight. Two of the three engine choices from the -200 were unchanged in the -300 but the General Electric CF6-80C2B1 was offered instead of the CF6-50E2 that was offered on the -200.[66]

The 747-300 name, which was proposed for a variant that was never launched, was revived for this new version, which was introduced in 1980. Swissair ordered the first 747-300 on 11 June 1980.[128] The 747-300 first flew on 5 October 1982. Swissair was the first customer to accept delivery on March 23, 1983.[129]

In addition to the passenger version other versions were available. The 747-300M has cargo capacity in the rear portion of the main deck similar to the -200M, but with the stretched upper deck it could carry more passengers.[130] The 747-300SR is a short range version to meet the need for a high capacity domestic model. Japan Airlines operated such aircraft with over 600 seats on Okinawa-Tokyo route and elsewhere. Boeing never launched a newly built freighter version of the 747-300 but did modify used passenger -300 models into freighters starting in 2000.[131]

A total of 81 aircraft were ordered, 56 for passenger use, 21 -300M and 4 -300SR versions.[132] The 747-300 was soon superseded by the launch of the more advanced 747-400 in 1985 just two years after the -300 entered service.[133] The last 747-300 was delivered in September 1990 to Sabena.[66][134]

747-400

The 747-400 is an improved model with increased range. It has Template:Ft to m wing tip extensions, Template:Ft to m winglets, and a new glass cockpit designed for a flight crew of two instead of three. It also has tail fuel tanks, revised engines, and a new interior. The longer range was used by some airlines to bypass traditional fuel stops, such as Anchorage.[135] The -400 was offered in passenger (400), freighter (400F), combi (400C), domestic (400D), extended range passenger (400ER) and extended range freighter (400ERF) versions. The freighter version does not have an extended upper deck.[136] The 747-400D was built for short range operations and does not include winglets, but these can be retrofitted.[137]

The passenger version first entered service in February 1989 with Northwest Airlines on the Minneapolis to Phoenix route.[138] The combi version entered service in September 1989 with KLM. The freighter version entered service in November 1993 with Cargolux. The 747-400ERF entered service in October 2002 with the 747-400ER entering service the following month with Qantas,[139] the only airline ever to order the passenger version.

The last passenger version of the 747-400 was delivered in April 2005 and Boeing announced in March 2007 that it has no plans to produce further passenger versions of the -400.[140] However, there were orders for 36 -400F and -400ERF freighters at the time of the announcement.[140]

In October 2007, a total of 670 747-400 series aircraft had been delivered.[141] At various times, the largest 747-400 operator has been Singapore Airlines,[142] Japan Airlines,[142] and British Airways.[143]

747 LCF "Dreamlifter"

The 747-400 Large Cargo Freighter or Dreamlifter[144] (originally called the 747 Large Cargo Freighter (LCF)[145]) is a Boeing designed modification of existing 747-400s to an outsized configuration to ferry Boeing 787 sub-assemblies for final assembly at Boeing facilities in Everett, Washington. Evergreen Aviation Technologies Corporation is completing modifications of 747-400s into Dreamlifters in Taiwan, Republic of China. The aircraft flew for the first time on 9 September 2006.[146] The aircraft is not certificated to carry passengers other than essential crew.[147] The aircraft's only intended purpose is for transporting sub-assemblies for the Boeing 787.[148] Two aircraft have been built. Two more are on order.[145]

747-8

Boeing announced a new 747 variant, the 747-8 (referred to as the 747 Advanced prior to launch) on November 14 2005, which will use same engine and cockpit technology as the 787 (It was decided to call it the 747-8 because of the technology it will share with the 787 Dreamliner). Boeing plans that the new design will be quieter, more economical and more environmentally friendly. The 747-8 is stretched to add more capacity/payload, which involved a lengthening from 232 to 251 feet (70.8 to 76.4 m); and therefore would surpass the Airbus A340-600 to become the world's longest airliner once the aircraft is in service.[149]

The passenger version, dubbed 747-8 Intercontinental or 747-8I, will be capable of carrying up to 467 passengers in a 3-class configuration and fly over 8,000 nmi to (14,815 km) at Mach 0.855. As a derivative of the already common 747-400, the 747-8 has the economic benefit of similar training and interchangeable parts.[150] The 747-8I is scheduled to enter service in 2010.[151]

Also offered is the 747-8 Freighter or 747-8F, which is a derivative to the 747-400ERF. The 747-8F is 251 feet (76.4 m) long and can accommodate 154 tons (140 tonnes) of cargo. To aid loading and unloading it features an overhead nose-door. It has 16% more payload capacity than the 747-400F and can hold seven additional standard air cargo containers. The 747-8F is scheduled to enter service in 2009.[152]

As of November 2007, there were 67 firm orders for the Boeing 747-8F, from Cathay Pacific (10), Atlas Air (12), Nippon Cargo Airlines (8), Cargolux (13), Emirates SkyCargo (10), Volga-Dnepr (5), Guggenheim Aviation Partners (4) and Korean Air (5). There were a total of 24 firm orders for the Boeing 747-8I, four from Boeing Business Jet and 20 from Lufthansa.[153]

Government and military variants

- C-19 - designation given by the U.S. Air Force to 747-100 used by some U.S. airlines which have modifications for use in the Civil Reserve Airlift Fleet.[154]

- VC-25 - the U.S. Air Force VIP version of 747-200B. The U.S. Air Force operates two in VIP configuration as the VC-25A. Tail numbers 28000 and 29000 are popularly known as Air Force One, which is technically the air traffic call sign for any United States Air Force aircraft carrying the U.S. President. Although based on the 747-200B, they contain many of the innovations introduced on the 747-400, such as an updated flight deck and engines. Partially completed aircraft from Everett, Washington were flown to Wichita, Kansas for final assembly, in contrast with civilian aircraft, which are completed in Everett.

- E-4B - formerly known as National Emergency Airborne Command Post (referred to colloquially as "Kneecap"), now referred to as National Airborne Operations Center (NAOC).

- YAL-1 - the experimental Airborne Laser, a component of the National Missile Defense plan.

- Shuttle Carrier Aircraft - Two 747s were modified to carry the Space Shuttle. One is a 747-100 (N905NA), acquired in 1974 from American Airlines; the other is a 747-100SR (N911NA), acquired from Japan Airlines in 1988. It first carried a shuttle in 1991.

- A number of other governments also use the 747 as a VIP transport, including Bahrain, Brunei, India, Iran, Japan, Kuwait, Oman, Pakistan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates. Several new Boeing 747-8 have been ordered by Boeing Business Jet for conversion to VIP Transport for several unidentified customers.[155]

- C-33 - proposed U.S. military version of 747-400, which was intended to augment the C-17 fleet, but the plan was canceled in favor of additional C-17 military transports.

- KC-33A - proposed 747 was also adapted as an aerial refueling tanker, and was bid against the DC-10-30 during the 1970s Advanced Cargo Transport Aircraft (ACTA) program which resulted in the KC-10A Extender. Before the Khomeini-led revolution, Iran bought four 747-100 aircraft with air refueling boom conversions to support a fleet of F-4 Phantoms.[156][157] It is not known whether these aircraft remain usable as tankers. Since then other proposals have emerged for adaptation of later 747-400 aircraft for this role.[156]

- 747 CMCA - This variant was considered by the U.S. Air Force as a Cruise Missile Carrier Aircraft during the development of the B-1 Lancer strategic bomber. It would have been equipped with up to 72 AGM-86 ALCM cruise missiles on rotary launchers. This was abandoned in favor of more conventional strategic bombers.

Undeveloped variants

Boeing has studied a number of 747 variants which have not gone beyond the concept stage.

747-300 Trijet

During the 1970s, Boeing studied the development of a shorter body, three-engined 747 to compete with the smaller Lockheed L-1011 TriStar and McDonnell Douglas DC-10, which had lower trip costs than the 747SP. The 747-300 Trijet would have more payload, range and passenger capacity. The center engine would have been fitted in the tail with an s-duct intake similar to the L-1011’s. However, engineering studies showed that a time consuming and costly redesign of the 747 wing would be necessary.[158]

747-500X/-600X/-700X

Boeing announced the 747-500X/-600X at the 1996 Farnborough Air Show.[74] The proposed models would combine the 747's fuselage with a new 251 ft (77 m) span wing derived from the 777. Other changes included new more powerful engines and increasing in the number of tires from two to four on the nose landing gear and from 16 to 20 on the main landing gear.[159]

The 747-500X concept featured an 18 ft (5.5 m) stretch to 250 ft (76.2 m) long and was to carry 462 passengers over a range up to 8,700 nautical miles (10,000 mi, 16,100 km), with a gross weight of over 1.0 Mlb (450 Mg).[159] The 747-600X concept featured a greater stretch to 279 ft (85 m) long with seating for 548 passengers, a range of up to 7,700 nmi (8,900 mi, 14,300 km) and a gross weight of 1.2 Mlb (540 Mg).[159] A third study concept, the 747-700X, would have combined the wing of the 747-600X with a widened fuselage, allowing it to carry 650 passengers over the same range as a 747-400.[74] The extent of changes over the previous 747 models, in particular the new wing for the 747-500X/-600X was estimated over $5 billion to develop.[74] Boeing was not able to attract enough interest to launch the aircraft.[160]

747X/X Stretch

As Airbus progressed with its A3XX study, in 2000 Boeing offered the market a 747 derivative as an alternative. This was a more modest proposal than the previous -500X/-600X, which would retain the 747's overall wing design, with an additional segment at the root increasing the span to 229 ft (70 m).[161] Power would have been supplied by either the Engine Alliance GP7172 or the Rolls-Royce Trent 600, which were also proposed for the 767-400ERX.[162] A new flight deck based on the 777's would be used. The 747X concept was to carry 430 passengers over ranges of up to 8,700 nmi (10,000 mi, 16,100 km). The 747X Stretch would be extended to 263 ft (80.2 m) long, allowing it to carry 500 passengers over ranges of up to 9,000 miles (7,800 nmi, 14,500 km).[161] Both would feature an interior based on the 777's signature architecture.[163] Freighter versions of the 747X and 747X Stretch were also studied.[164]

Like the predecessor, the 747X family was unable to garner enough interest to justify production, and was shelved along with the 767-400ERX in March 2001, when Boeing announced the Sonic Cruiser concept.[76] While the 747X design had been less costly than the 747-500X/-600X, it was criticized for not offering a sufficient advance from the existing 747-400. While the 747X did not make it beyond the drawing board, the 747-400X, which was being developed concurrently, did move into production to become the 747-400ER.[165]

747-400XQLR

Following the termination of the 747X program, Boeing continued to study improvements which could be made to the 747. The 747-400XQLR (Quiet Long Range) would have increased range of 7,980 nmi (9,200 mi, 14,800 km), with improvements to improve efficiency and reduce noise.[166] Improvements studied included raked wingtips similar to those used on the 767-400ER, and a sawtooth engine nacelle for noise reduction.[167] While the 747-400XQLR did not move to production, many features were picked up for the 747 Advanced, which has now been launched as the 747-8.

Specifications

| Measurement | 747-100 | 747-200B | 747-300 | 747-400 747-400ER |

747-8I |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cockpit Crew | Three | Two | |||

| Typical Seating capacity | 452 (2-class) 366 (3-class) |

524 (2-class) 416 (3-class) |

467 (3-class) | ||

| Length | 231 ft 10 in (70.6 m) | 250 ft 8 in (76.4 m) | |||

| Wingspan | 195 ft 8 in (59.6 m) | 211 ft 5 in (64.4 m) | 224 ft 9 in (68.5 m) | ||

| Height | 63 ft 5 in (19.3 m) | 63 ft 8 in (19.4 m) | 63 ft 6 in (19.4 m) | ||

| Weight empty | 358,000 lb (162,400 kg) |

383,000 lb (174,000 kg) |

392,800 lb (178,100 kg) |

393,263 lb (178,756 kg) ER: 406,900 lb (184,600 kg) |

410,000 lb (185,972 kg) |

| Maximum takeoff weight | 735,000 lb (333,390 kg) |

833,000 lb (377,842 kg) |

875,000 lb (396,890 kg) ER: 910,000 lb (412,775 kg) |

970,000 lb (439,985 kg) | |

| Cruising speed (at 35,000 ft altitude) |

Mach 0.84 (555 mph, 895 km/h, 481 knots ) |

Mach 0.85 (567 mph, 913 km/h, 487 kt) ER: Mach 0.855 (570 mph, 918 km/h, 493 kt) |

Mach 0.855 (570 mph, 918 km/h, 493 kt) | ||

| Maximum speed | Mach 0.89 (587 mph, 945 km/h, 510 knots) |

Mach 0.92 (608 mph, 977 km/h, 527 knots) |

|||

| Takeoff run at MTOW | 10,466 ft (3,190 m) | 10,893 ft (3,320 m) | 9,902 ft (3,018 m) ER: 10,138 ft (3,090 m) |

10,138 ft (3,090 m) | |

| Range fully loaded | 5,300 nmi (9,800 km) |

6,850 nmi (12,700 km) |

6,700 nmi (12,400 km) |

7,260 nmi (13,450 km) ER: 7,670 nmi (14,205 km) |

8,000 nmi (14,815 km) |

| Max. fuel capacity | 48,445 U.S. gal (183,380 L) |

52,410 U.S. gal (199,158 L) | 57,285 U.S. gal (216,840 L) ER: 63,705 U.S. gal (241,140 L) |

64,225 U.S. gal (243,120 L) | |

| Engine models (x 4) | PW JT9D-7A RR RB211-524B2 |

PW JT9D-7R4G2 GE CF6-50E2 RR RB211-524D4 |

PW JT9D-7R4G2 GE CF6-80C2B1 RR RB211-524D4 |

PW 4062 GE CF6-80C2B5F RR RB211-524G/H ER: GE CF6-80C2B5F |

GEnx-2B67 |

| Engine thrust (per engine) | PW 46,500 lbf (207 kN) RR 50,100 lbf (223 kN) |

PW 54,750 lbf (244 kN) GE 52,500 lbf (234 kN) RR 53,000 lbf (236 kN) |

PW 54,750 lbf (244 kN) GE 55,640 lbf (247 kN) RR 53,000 lbf (236 kN) |

PW 63,300 lbf (282 kN) GE 62,100 lbf (276 kN) RR 59,500/60,600 lbf (265/270 kN) ER: GE 62,100 lbf (276 kN) |

66,500 lbf (296 kN) |

Sources: 747 specifications,[168] 747 airport report[169]

The parasitic drag is given by ½ f ρair v² in which f is the product of a drag coefficient CDp and the wing area. For the 747, CDP is 0.022, and the wing area is 5500 square feet, so that f equals about 121 ft² or 11.2 m².[170]

Deliveries

| 2008 | 2007 | 2006 | 2005 | 2004 | 2003 | 2002 | 2001 | 2000 | 1999 | 1998 | 1997 | 1996 | 1995 | 1994 | 1993 | 1992 | 1991 | 1990 | 1989 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | 15 | 14 | 13 | 15 | 19 | 27 | 31 | 25 | 47 | 53 | 39 | 26 | 25 | 40 | 56 | 61 | 64 | 70 | 45 |

| 1988 | 1987 | 1986 | 1985 | 1984 | 1983 | 1982 | 1981 | 1980 | 1979 | 1978 | 1977 | 1976 | 1975 | 1974 | 1973 | 1972 | 1971 | 1970 | 1969 |

| 24 | 23 | 35 | 24 | 16 | 22 | 26 | 53 | 73 | 67 | 32 | 20 | 27 | 21 | 22 | 30 | 30 | 69 | 92 | 4 |

- Last updated: 6 December 2007[171]

Preserved aircraft

As increasing numbers of "classic" 747-100 and 747-200 series have been retired, some have found their way into aircraft museums. They include:

- Boeing 747-100, City of Everett, the first 747 and prototype at the Museum of Flight, Seattle, Washington, USA[172]

- KLM 747-200(SUD) PH-BUK "Louis Blériot" at National Aviation Theme Park Aviodrome, Lelystad, Netherlands

- Qantas 747-200 VH-EBQ "City of Bunbury" at Qantas Founders Outback Museum, Longreach Airport, Longreach, Queensland, Australia

- South African Airways 747-200 ZS-SAN "Lebombo" and 747SP ZS-SPC "Maluti" at Rand Airport, Johannesburg, South Africa

- Lufthansa 747-200 D-ABYM "Schleswig-Holstein" at Technik Museum Speyer, Speyer, Germany

- Air France 747-100 F-BPVJ at Musée de l'Air et de l'Espace, Le Bourget airport, Paris, France

- Iran Air 747SPs EP-IAA and EP-IAC and 747-200F EP-ICC at Tehran Aerospace Exhibition, Tehran, Iran

- Korean Air 747-200 HL7463 at Jeongseok Aviation Center, Jeju, South Korea[173]

- Northwest Airlines' first 747 at National Air and Space Museum, Washington, D.C.[174]

Incidents

As of May 2007, there were a total of 45 hull-loss accidents involving 747s,[175] with 3,707 fatalities.[176]

Very few crashes have been attributed to design flaws of the 747. The Tenerife disaster was a result of pilot error, ATC error and communications failure, while Japan Airlines Flight 123 was the consequence of improper aircraft repair. United Airlines Flight 811, which suffered an explosive decompression mid-flight on February 24 1989, subsequently had NTSB issuing a recommendation to have all similar 747-200 cargo doors modified. TWA Flight 800, a 747-100 that exploded mid-air on 17 July 1996, led to the Federal Aviation Administration proposing a rule requiring the installation of an inerting system in the center fuel tank for most large aircraft.

Notable incidents

- The first crash of a 747 took place on 20 November 1974 when Lufthansa Flight 540 crashed in Nairobi killing 59 people.

- The Tenerife disaster resulted in 583 fatalities when a KLM 747 collided into a Pan American World Airways 747 in heavy fog at Tenerife Airport on 27 March 1977. This is the highest death toll in any aviation accident in history.[177]

- An Air India Flight 855 Boeing 747 crashed into the sea off the coast of Mumbai (Bombay) on New Year's Day, 1978. All passengers and crew were killed. Many residents of sea-front houses in Mumbai witnessed the incident.

- British Airways Flight 9, on 24 June 1982, flew into a volcanic dust cloud, resulting in all four engines failing. After exiting the cloud, three engines continued working, allowing the aircraft to land safely in Jakarta.

- Korean Air Lines Flight 007 was a 747-230B which was shot down by the Soviet Air Force on September 1, 1983. All 269 passengers and crew aboard were killed.

- Air India Flight 182 was a 747-237B that exploded on 23 June 1985. All 329 on board were killed. Up until 11 September 2001, the Air India bombing was the single deadliest terrorist attack involving aircraft.

- Japan Airlines Flight 123 (a 747SR-46 Short Range) was lost on 12 August 1985 when most of its vertical stabilizer fell off while at cruising altitude. The pilots kept it in the air for just over thirty minutes, but eventually crashed, causing 520 fatalities. It is the worst single-aircraft disaster in aviation history.[178] An inadquate pressure bulkhead repair was later determined to be the cause. The airline later opened a safety centre to train all employees of the importance of safety.

- South African Airways Flight 295, a 747-244B Combi Helderberg en route from Taipei to Johannesburg on 28 November 1987, crashed into the ocean off Mauritius after an in-flight fire in the rear cargo hold resulted in loss of control and destruction of the aircraft. All 159 people on board were killed.

- Pan Am Flight 103, a 747-121, on 21 December 1988 crashed near Lockerbie, Scotland as a result of a bomb in passenger luggage. A Libyan national was eventually convicted.

- United Airlines Flight 811, a Boeing 747-122, suffered on 24 February 1989 an explosive decompression shortly after takeoff from Honolulu, Hawaii, caused by a cargo door which burst open during flight. Nine passengers were blown out of the plane, but the pilots managed to land safely at Honolulu.

- El Al Flight 1862 was a 747-258F which crashed shortly after departure from Amsterdam Schiphol on 4 October 1992. Engines no. 3 and 4 detached after takeoff and as a result the flight crew lost control and the crippled 747 crashed into the Klein-Kluitberg apartments in Bijlmermeer at high speed. The sole passenger and all three crew were killed as well as 39 on the ground.

- TWA Flight 800, a 747-131, exploded during climb from John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York on 17 July 1996, bound for Charles de Gaulle Airport in Paris, killing all 230 people. Changes in fuel tank management were implemented after the crash.

- Saudi Arabian Airlines Flight 763, operated by a 747-168B, and Air Kazakhstan Flight 1907, a Ilyushin IL-76, collided in midair over India killing all people on board both aircraft.

- Korean Air Flight 801, a 747-3B5 crashed into a hillside on 6 August 1997, before landing at Antonio B. Won Pat International Airport, Guam, killing all but 26 of its passengers.

- Singapore Airlines Flight 006, a 747-412 flying on a Singapore to Los Angeles via Taipei route rammed into construction equipment On 31 October 2000, while attempting to take off from a closed runway at Chiang Kai Shek International Airport, caught fire and was destroyed, killing 79 passengers and three crew members. The accident prompted the airline to change the flight number of this route from 006 to 030 and to remove the "Tropical Megatop" livery on the accident aircraft's sister ship.[179]

- China Airlines Flight 611, a 747-209B, broke-up mid flight on 25 May 2002, en route to Hong Kong International Airport from Chiang Kai Shek International Airport in Taipei. All on board lost their lives. Metal fatigue at the site of a previous repair was cited as a cause.

References

- Notes

- ^ BBC News Woman to build house out of 747 BBC News. Retrieved: 11 December 2007.

- ^ Creating Worlds: Adventures Aviation (review) Amazon.com. Retrieved: 11 December 2007.

- ^ a b "Great Planes-Boeing 747", Discovery Channel. Retrieved: 28 October 2007.

- ^ Pilot of the Jet Age Time magazine. Retrieved: 13 December 2007.

- ^ Boeing's Path to the 787 Dreamliner, USA Today. Retrieved: 13 December 2007.

- ^ "Technical Characteristics – Boeing 747-400", Boeing Commercial Airplanes . Retrieved: 29 April 2006.

- ^ 747 Fleet's Age at Issue During Flight 800 Hearing, New York Times. 12 December 1997.

- ^ "Model 747", The Boeing Company. Retrieved: 13 December 2007.

- ^ Orders and Deliveries The Boeing Company. Retrieved: 25 November 2006.

- ^ The Boeing Story Part IV, Associated Content. 27 July 2007.

- ^ Boeing Multimedia Image Gallery 707, Boeing. Retrieved: 8 December 2007.

- ^ Aerospace Notebook: After a struggle, Sutter's 747 tale got told, Seattle Post-Intelligencer. 2 November 2005.

- ^ Lockheed C-5 Galaxy, Partners in Freedom, NASA. 2000.

- ^ "In review: 747, Creating the World’s First Jumbo Jet and Other Adventures from a Life in Aviation." Aviation Week and Space Technology, Vol. 165, No. 9, 4 September 2006, p. 53.

- ^ a b c d History - "747 Commercial Transport", The Boeing Company. Retrieved: 29 April 2006.

- ^ Innovators: Juan Trippe, PBS. Retrieved 17 December 2007

- ^ a b Building the 777, Zenith Press. Retrieved: 13 December 2007.

- ^ a b c d "The Boeing 747", Judy Rumerman, U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission. Retrieved: 30 April 2006.

- ^ Irving 1994, p. 282.

- ^ Sutter 2006, p. 96-97.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

milestonewas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b "Passenger Planes: Boeing 747", David Noland, "Info please." (Pearson Education). Retrieved: 30 April 2006.

- ^ Irving 1994, p. 359.

- ^ In review: 747, Creating the World’s First Jumbo Jet and Other Adventures from a Life in Aviation, Aviation Week and Space Technology, Vol. 165, No. 9, September 4, 2006, p. 53.

- ^ GE Aviation:CF6, GE Aviation. Retrieved: 9 December 2007.

- ^ a b Mechanical Engineering 100 Years of Flight Retrieved: 9 December 2007.

- ^ a b Sutter 2006, p.121, 128-131.

- ^ BBC news:Air travel, a supersonic future? Retrieved: 9 December 2007.

- ^ The Boeing Story Part IV, Associated Content. Retrieved: 9 December 2007.

- ^ Futuristics: Supersonic Transportation, University of California-Berkeley. Retrieved: 9 December 2007.

- ^ "The Concorde Supersonic Transport", T.A. Heppenheimer, U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission. Retrieved: 30 April 2006.

- ^ "Everett and Renton react differently to Boeing", Puget Sound Business Journal. September 26, 2003 26 September 2003.

- ^ a b "Major Production Facilities - Everett, Washington", Boeing Commercial Airplanes. Retrieved: 28 April 2007.

- ^ "Boeing legend Malcolm Stamper dies", Seattle Times. 17 June 2005.

- ^ Irving 1994, p. 310.

- ^ Irving 1994, p. 365.

- ^ Irving 1994, p. 383.

- ^ "All but off the Ground." Time. 4 October 1968.

- ^ "The Giant Takes Off". Time. Retrieved: 13 December 2007.

- ^ "Boeing 747, the "Queen of the Skies," Celebrates 35th Anniversary", The Boeing Company press release, 9 February 2004.

- ^ Irving 1994, p. 417–418.

- ^ Irving 1994, p. 428.

- ^ Uijt de Haag, P.A., Smetsers, R.C., Witlox, H.W., Krus H.W. and Eisenga, A.H. "Evaluating the risk from depleted uranium after the Boeing 747-258F crash in Amsterdam, 1992." Journal of Hazardous Materials Volume 76, issue 1, 28 August 2000, p. 39-58. Boeing 747-258F crash, Amsterdam, 1992. Retrieved: 16 May 2007.

- ^ van der Keur, Henk. "Uranium Pollution from the Amsterdam 1992 Plane Crash", Laka Foundation, May 1999. Retrieved: 16 May 2007.

- ^ Irving 1994, p. 441-446.

- ^ Trouble with Jumbo "The Trouble with Jumbo." Time, 26 September 1969.

- ^ Irving 1994, p. 436.

- ^ "The Paris Air Show in facts and figures", Reuters. 14 June 2007.

- ^ "Boeing 747-400", Jane's All the World's Aircraft. 31 October 2000.

- ^ Irving 1994, p. 437-438.

- ^ "First A380 Flight on 25-26 October", Singapore Airlines. 16 August 2007.

- ^ Museum of Flight Foundation v. U.S.A., Planned Giving Design Center. Retrieved: 15 December 2007.

- ^ a b Norris 1997, p. 48.

- ^ Innovators: Juan Trippe, PBS. Retrieved 17 December 2007

- ^ Orders and Deliveries The Boeing Company Retrieved: 10 December 2007.

- ^ Executive Decision, Movie Ramblings. Retrieved 17 December 2007

- ^ Air Force One, Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 17 December 2007

- ^ "How the Airbus A380 Works - Triumph or Mistake?", Howstuffworks. Retrieved: 29 April 2006.

- ^ Once a Laggard, Boeing 747 Gets a Sharp New Lift, International Herald Tribune. Retrieved: 10 December 2007.

- ^ Fuel consumption for moderately loaded 747 (70% of seats occupied) offers a less than 5% fuel savings compared to a fully occupied 747 (100% of seats occupied), thus illustrating the high costs that results from operating the large aircraft when there is insufficient passenger demand. Airline reporting on fuel consumption Miljominsteriet (Danish Environmental Protection Agency). Retrieved: 13 December 2007.

- ^ a b Historic American Airlines Aircraft Models, American Airlines. Retrieved: 13 December 2007.

- ^ Turning Today's Challenges into Opportunities for Tomorrow, The Boeing Company Retrieved: 10 December 2007.

- ^ Smith, Bruce A. "Boeing Shuns Very Large Jets While Aiming for Longer Range." Aviation Week and Space Technology, January 1, 2001, p. 28-29. See also 747X vs A380 How to Reduce Congestion, Department of Aerospace and Ocean Engineering, Virginia Tech Retrieved: 10 December 2007.

- ^ Commercial Transport Market Still in Rough Shape, Aviation Week and Space Technology. Retrieved: 10 December 2007.

- ^ A380 buyer keeps mum about possible luxuries aboard cruise ship of the skies, Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved 13 December 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Boeing 747 Classics, The Boeing Company. Retrieved: 15 December 2007.

- ^ Solutions Center, The Boeing Company. Retrieved: 13 December 2007.

- ^ Boeing 747SP, Airliners.net. Retrieved: 23 November 2007.

- ^ Aircraft Owner's and Operator's Guide: 747-200/300, Aircraft Commerce. Retrieved: 13 December 2007.

- ^ "Boeing 747-300", Airliners.net. Retrieved: 25 November 2007.

- ^ Lawrence and Thornton, p. 54. Deep Stall: The Turbulent Story of Boeing Commercial Airplanes, Ashgate Publishing, 2005, ISBN 0754646262.

- ^ "J.A.L. Orders 15 More of Boeing's 747-400's", New York Times. July 1, 1988.

- ^ The Boeing 747, U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission. Retrieved: 10 December 2007.

- ^ a b c d e "Boeing Outlines the "Value" of Its 747 Plans" Boeing, 2 September 1996. Cite error: The named reference "boe_1996" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "BA warms to A3XX plan", Flight International, 19 March 1997.

- ^ a b "Boeing Shelves 747X to Focus on Faster Jet", People's Daily, 30 March 2001.

- ^ Taylor, Alex III. "Boeing's Amazing Sonic Cruiser ..." Fortune, 9 December 2002.

- ^ "Boeing Launches New, Longer-Range 747-400", Boeing, 28 November 2000.

- ^ Boeing's Reborn 747, Business Week. 16 November 2005.

- ^ "Boeing Launches New 747-8 Family", The Boeing Company. 14 November 2005.

- ^ Singapore Airlines boosts Airbus fleet with additional A380 orders, [[Airbus S.A.S.], 20 December 2006.

- ^ "Emirates Airlines reaffirms commitment to A380 and orders additional four", [[Airbus S.A.S.], 7 May 2007.

- ^ Robertson, David. "Airbus will lose €4.8bn because of A380 delays." The Times, 3 October 2006.

- ^ Big plane, big problems CNN. Retrieved: 13 December 2007.

- ^ A380 superjumbo lands in Sydney, , BBC News. Retrieved: 10 December 2007.

- ^ El Al History page, El Al Airlines. Retrieved: 18 October 2007.

- ^ "Ask Us - Largest Plane in the World", Aerospaceweb.org. Retrieved: 29 April 2006.

- ^ Goleta Air and Space Museum - Boeing Jetliner Prototypes and Testbeds Retrieved: 12 December 2007.

- ^ GE-Aviation:GE90-115B Prepares For Flight Aboard GE's 747 Flying Testbed Retrieved: 12 December 2007.

- ^ GEnx Engine Completes Flight Tests on 747 Testbed Retrieved: 12 December 2007.

- ^ Goleta Air and Space Museum - Boeing Jetliner Prototypes and Testbeds Retrieved: 12 December 2007.

- ^ a b Sutter 2006, p. 93.

- ^ Bowers 1989, p. 508.

- ^ Boeing 747-400 Airport Planning report, section 2.0, Boeing, December 2002, The Boeing Company. Retrieved: 13 December 2007.

- ^ Boeing 747-100/200/300 Technical Specifications, The Boeing Company Retrieved: 13 December 2007.

- ^ Boeing 747-8 Technical Specifications, The Boeing Company. Retrieved: 13 December 2007.

- ^ Sutter 2006, p. 121-122.

- ^ Special Report:Air India Flight 182, airdisaster.com. Retrieved: 13 December 2007.

- ^ Her Majesty the Queen Against Ripudaman Singh Malik and Ajaib Singh Bagri Supreme Court of British Columbia. Retrieved: 13 December 2007.

- ^ Boeing 747, Aircraft Spotting. Retrieved: 7 December 2007.

- ^ Saudia Orders 4 Boeing 747's Retrieved: 12 December 2007.

- ^ Norris 1997, p. 53.

- ^ FAA Regulatory and Guidance Library, FAA. Retrieved: 12 December 2007. See reference to Supplementary Type Certificates for freighter conversion.

- ^ Fast Facts: 747, The Boeing Company. Retrieved 16 December 2007

- ^ Boeing Commercial Airplanes - 747 Classics Technical Specs, The Boeing Company. Retrieved: 12 December 2007.

- ^ Air Transportation by Robert M. Kane

- ^ 747 Milestones, The Boeing Company. Retrieved 17 December 2007

- ^ Bowers 1989, p. 516-517.

- ^ "Boeing 747-146B/SR/SUD aircraft"., Airliners.net

- ^ JAL Aircraft Collection, Japan Airlines. Retrieved: 15 December 2007.

- ^ of NANJING must be known, Japan Corporate News Network. Retrieved: 15 December 2007.

- ^ 747 windows, Plexoft. Retrieved: 15 December 2007.

- ^ a b c d e Aircraft Owner's and Operator's Guide, Aircraft-Commerce.com. Retrieved: 5 December 2007.

- ^ Boeing 747 - About the 747 Family, The Boeing Company. Retrieved: 6 December 2007.

- ^ Boeing 747-200, CivilAviation.eu. Retrieved: 15 December 2007.

- ^ Air France F-BTDG Airfleets, Airfleets. Retrieved: 6 December 2007.

- ^ 747-2B3BM(SUD) Aircraft Pictures, Airliners.net. Retrieved: 6 December 2007.

- ^ 747 background, The Boeing Company. Retrieved: 13 December 2007.

- ^ 747 Classics Technical Specifications, The Boeing Company. Retrieved: 6 December 2007.

- ^ 747-200 Classic by AETI, Flight Simulators. Retrieved: 15 December 2007.

- ^ a b c The Story of the Baby 747, 747sp.com. Retrieved: 15 December 2007.

- ^ Kane 2003, p. 546.

- ^ "Top 10 Most Notable-Looking Post-War Aircraft"., Aviation, retrieved: 15 December 2007

- ^ "747 SP"., 747sp.com. Retrieved: 15 December 2007.

- ^ a b "Boeing 747-300"., airliners.net

- ^ Interiors, Airchive.com. Retrieved 17 December 2007

- ^ Flyer talk, Flyer Talk, retrieved: 15 December 2007

- ^ Seven Series, The Boeing Company, retrieved: 15 December 2007.

- ^ 747 Program Milestones, The Boeing Company. Retrieved 17 December 2007.

- ^ 747-300, Zap16.com. Retrieved: 17 December 2007.

- ^ Boeing Company News releases, The Boeing Company. Retrieved: 17 December 2007.

- ^ Boeing Commercial Airplanes - 747 Classics Technical Specifications, The Boeing Company. Retrieved: 6 December 2007

- ^ Lawrence, Philip K. (2005). Deep Stall: The Turbulent Story of Boeing. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 0754646262.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) Retrieved 12 December 2007. - ^ Seven series, The Boeing Company. Retrieved: 17 December 2007.

- ^ JAL 2007, Japan Airlines. Retrieved: 14 December 2007.

- ^ Boeing 747-400 Freighter Family, The Boeing Company. Retrieved 17 December 2007.

- ^ JAL 1998, Japan Airlines. Retrieved: 17 December 2007.

- ^ Norris 1997, p. 88.

- ^ Boeing 747-400ER Family, The Boeing Company. Retrieved: 16 October 2007.

- ^ a b "747-400 passenger is no more", Seattlepi.com, 17 March 2007.

- ^ "Commercial orders"., The Boeing Company. Retrieved: 14 December 2007.

- ^ a b "Boeing News release"., The Boeing Company. Retrieved: 14 December 2007.

- ^ Boeing News archive, The Boeing Company. Retrieved: 14 December 2007.

- ^ "Cargo freighter"., The Boeing Company

- ^ a b Evergreen Aviation press release, 20 July 2007, Evergreen Aviation. Retrieved: 17 December 2007.

- ^ "Boeing 747 Large Cargo Freighter Completes First Flight". Boeing press release, 9 September 2006.

- ^ "Boeing 747 Dreamlifter Achieves FAA Certification", The Boeing Company, 4 June 2007. Retrieved: 17 December 2007.

- ^ Dreamlifter to become fixture in Lowcountry sky, Charleston Regional Business Journal. Retrieved: 15 December 2007.

- ^ Boeing launches 747-8, Flug Revue. Retrieved: 8 December 2007.

- ^ Boeing freezes The 747-8I design, Aviation Week. Retrieved: 8 December 2007.

- ^ Lufthansa launches 747-8I, Air Transport World. Retrieved: 8 December 2007.

- ^ Boeing 747-8 Freighter, Deagal. Retrieved: 8 December 2007.

- ^ Boeing, Lufthansa Announce Order for 747-8 Intercontinental, The Boeing Company. Retrieved: 15 December 2007.

- ^ "Boeing C-19"., Global Security. Retrieved: 16 December 2007.

- ^ Boeing nets 57 new orders, including big VIP planes, Seattle Times. Retrieved: 14 December 2007.

- ^ a b "KC-33A: Closing the Aerial Refuelling and Strategic Air Mobility Gaps", Air Power Australia Analysis APA-2005-02, 16 April, 2005. Retrieved: 17 December 2007.

- ^ Boeing advanced 747 as tanker, Leeham Company, September 11, 2007. Retrieved: 17 December 2007.

- ^ The Story of the Baby 747, Boeing 747SP website. Retrieved 16 December 2007

- ^ a b c Patterson, James W. "Impact of New Large Aircraft on Airport Design", Federal Aviation Administration, March 1998. Retrieved: 17 December 2007.

- ^ "BA warms to A3XX plan", Flight International, 19 March 1997. Retrieved: 17 December 2007.

- ^ a b "Boeing 747 Celebrates 30 Years In Service", The Boeing Company, 2 September 1996. Retrieved: 17 December 2007.

- ^ "Boeing Commits To Produce New Longer-Range 767-400ER", The Boeing Company, September 13, 2000. Retrieved: 17 December 2007.

- ^ "Customer Symposium Highlights Future Boeing 747 Models", The Boeing Company, 29 June 2000. Retrieved: 17 December 2007.

- ^ "Boeing In No Hurry to Launch 747X" Aviation Week, 24 July 2000. Retrieved: 17 December 2007.

- ^ "Boeing Launches New, Longer-Range 747-400", The Boeing Company. Retrieved: 17 December 2007.

- ^ "Boeing Offers New 747-400X Quiet Longer Range Jetliner", The Boeing Company. 17 December 2007.

- ^ "Boeing Proposes 747-400X Quiet Longer Range", Flug Revue Online, May 2002. Retrieved: 17 December 2007.

- ^ 747 specifications, The Boeing Company. Retrieved 16 December 2007.

- ^ 747 Airplane Characteristics for Airport Planning, The Boeing Company. Retrieved: 15 December 2007.

- ^ "Calculating and Plotting Parasite Drag". Aerodynamics Text. Retrieved: 17 December 2007.

- ^ Orders and Deliveries, The Boeing Company. Retrieved: 17 December 2007 Also see http://active.boeing.com/commercial/orders/index.cfm?content=userdefinedselection.cfm&pageid=m15527

- ^ Aircraft and Space Craft, Boeing 747-121, Museum of Flight. Retrieved: 15 December 2007.

- ^ "The Blue Sky"., thebluesky.info. Retrieved: 17 December 2007.

- ^ Historic Aircraft Lands at Air and Space Museum, WTOP News, 16 January 2007.

- ^ Boeing 747 Accident summary, Aviation-Safety.net, 5 May 2007. Retrieved: 17 December 2007.

- ^ Boeing 747 Accident Statistics, Aviation-Safety.net, 5 July 2005. Retrieved: 17 December 2007.

- ^ "1977: Hundreds dead in Tenerife plane crash", "On This Day." BBC News. Retrieved: 26 May 2006.

- ^ Japan marks air crash anniversary, BBC News. Retrieved: 12 August 2005.

- ^ "Rushing to Die, The Crash of Singapore Airlines flight 006"., Airline Safety. Retrieved 17 December 2007.

- Bibliography

- Bowers, Peter M. Boeing aircraft since 1916. London: Putnam Aeronautical Books, 1989. ISBN 0-85177-804-6.

- Irving, Clive. Wide Body: The Making of the Boeing 747. Philadelphia: Coronet, 1994. ISBN 0-340-59983-9.

- Kane, Robert M. Air Transportation. Dubuque, IA: Kendall Hunt Publishing Company, 2003. ISBN 0-75753-180-6.

- Lawrence, Philip K. and Thornton, David Weldon. Deep Stall: The Turbulent Story of Boeing Commercial Airplanes. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Co., 2005, ISBN 0-75464-626-2.

- Norris, Guy and Wagner, Mark. Boeing 747. St. Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing Co., 1997. ISBN 0-7603-0280-4.

- Shaw, Robbie. Boeing 747 (Osprey Civil Aircraft series). London: Osprey, 1994. ISBN 1-85532-420-2.

- Sutter, Joe. 747: Creating the World's First Jumbo Jet and Other Adventures from a Life in Aviation. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Books, 2006. ISBN 978-0-06-088241-9.

- Wilson, Stewart. Airliners of the World. Fyshwick, Australia: Aerospace Publications Pty Ltd., 1999. ISBN 1-875671-44-7.

External links

- Boeing 747 family page and 747 history page at Boeing.com

- Boeing 747 e-brochure - Flash animation

- 747-100 & 200, 747-300, 747-400 pages on Airliners.net

- Boeing 747SP web site - Production Lists and Photo Gallery

- Boeing 747 profile and Boeing 747 aviation archive on FlightGlobal.com

- Boeing 747 Information & History on GoCalipso.com

Related content

- Boeing fuselage Section 41

- G-BDXJ, 747-200 used in several film/TV productions

- Joseph F. Sutter, engineering manager for early 747 models

Template:Giant aircraft Related development

- Boeing 747SP

- Boeing 747-400

- Boeing 747 Large Cargo Freighter

- Boeing 747-8

- E-4 Nightwatch

- VC-25 Air Force One

- Boeing C-33

- Boeing YAL-1 Airborne Laser

- Shuttle Carrier Aircraft

- Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA)

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists