Odin

Odin (Old Norse Óðinn, also known as Oden), is considered the chief god in Norse mythology and Norse paganism. Like the Anglo-Saxon Woden it is descended from Proto-Germanic *Wōđinaz or *Wōđanaz.

His name is related to óðr, meaning "fury", "excitation", "mind" or "poetry". His role, like many of the Norse pantheon, is complex. He is a god of wisdom, war, battle and death. He is also attested as being a god of magic, poetry, prophecy, victory and the hunt.

Characteristics

Odin is an ambivalent deity. Old Norse (Viking Age) connotations of Odin lie with "poetry, inspiration" as well as with "fury, madness and the wanderer." Odin sacrificed his left eye at Mímir's spring in order to gain the Wisdom of Ages. Odin gives to worthy poets the mead of inspiration, made by the dwarfs, from the vessel Óð-rœrir.[1]

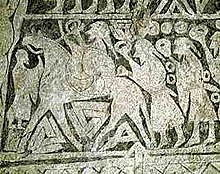

Odin is associated with the concept of the Wild Hunt, a noisy, bellowing movement across the sky, leading a host of slain warriors.

Consistent with this, Snorri Sturluson's Prose Edda depicts Odin as welcoming the great, dead warriors who have died in battle into his hall, Valhalla, which, when literally interpreted, signifies the hall of the slain. The fallen, the einherjar, are assembled and entertained by Odin in order that they in return might fight for, and support, the gods in the final battle of the end of Earth, Ragnarök.

He is also a god of war, appearing throughout Norse myth as the bringer of victory. In the Norse sagas, Odin sometimes acts as the instigator of wars, and is said to have been able to start wars by simply throwing down his javelin Gungnir, and/or sending his valkyries, to influence the battle toward the end that he desires. The Valkyries are Odin's beautiful battle maidens that went out to the fields of war to select and collect the worthy men who died in battle to come and sit at Odin's table in Valhalla, feasting and battling until they had to fight in the final battle, Ragnarök. Odin would also appear on the battle-field, sitting upon his eight-legged horse Sleipnir, with his two ravens, one on each shoulder, Hugin (Thought) and Munin (Memory), and two wolves(Geri and Freki) on each side of him.

Odin is also associated with trickery, cunning, and deception. Most sagas have tales of Odin using his cunning to overcome adversaries and achieve his goals, such as swindling the blood of Kvasir from the dwarves.

Origins

Worship of Odin may date to Proto-Germanic paganism. The Roman historian Tacitus may refer to Odin when he talks of Mercury. The reason is that, like Mercury, Odin was regarded as Psychopompos,"the leader of souls."

Because Odin is closely connected with a horse and spear and transformation/shape shifting into animal shapes an alternatively theory of origin contends that Odin or at least some of his key characteristics may have arisen just prior to the sixth century as a nightmareish horse god (Echwaz), later signified by the eight legged Sleipner. The original function of this horse was to carry the dead to wherever they were going and to sometimes snack on their flesh. Some support for Odin as a late comer to the Scandinavian Norse pantheon can be found in the Sagas where, for example, at one time he is thrown out of Asgard by the other gods - a seemingly unlikely tale for a well established "all father". Scholars who have linked Odin with the "Death God" template include E. A. Ebbinghaus, Jan de Vries and Thor Templin. The later two also link Loki and Odin as being one-and-the-same until the early Norse Period.

Scandinavian Óðinn emerged from Proto-Norse *Wōdin during the Migration period, Vendel artwork (bracteates, image stones) depicting the earliest scenes that can be aligned with the High Medieval Norse mythological texts. The context of the new elites emerging in this period aligns with Snorri's tale of the indigenous Vanir who were eventually replaced by the Aesir, intruders from the Continent.[2]

Parallels between Odin and Celtic Lugus have often been pointed out: both are intellectual gods, commanding magic and poetry. Both have ravens and a spear as their attributes, and both are one-eyed. Julius Caesar (de bello Gallico, 6.17.1) mentions Mercury as the chief god of Celtic religion. A likely context of the diffusion of elements of Celtic ritual into Germanic culture is that of the Chatti, who lived at the Celtic-Germanic boundary in Hesse during the final centuries before the Common Era. (It must be remembered that Odin in his Proto-Germanic form was not the chief god, but that he only gradually replaced Tyr during the Migration period.)

Blót

It is attested in primary sources that sacrifices were made to Odin during blóts. Adam of Bremen relates that every ninth year, people assembled from all over Sweden to sacrifice at the Temple at Uppsala. Male slaves and males of each species were sacrificed and hung from the branches of the trees.

As the Swedes had the right not only to elect their king but also to depose him, the sagas relate that both King Domalde and King Olof Trätälja were sacrificed to Odin after years of famine. It has been argued that the killing of a combatant in battle was to give a sacrificial offering to Odin. The fickleness of Odin in war was well-documented; in Lokasenna, Loki taunts Odin for his inconsistency.

Sometimes sacrifices were made to Odin to bring about changes in circumstance. A notable example is the sacrifice of King Víkar that is detailed in Gautrek's Saga and in Saxo Grammaticus' account of the same event. Sailors in a fleet being blown off course drew lots to sacrifice to Odin that he might abate the winds. The king himself drew the lot and was hanged.

Sacrifices were probably also made to Odin at the beginning of summer (mid April, actually--summer being reckoned essentially the same as did the Celt, at Beltene, Calan Mai [Welsh], which is Mayday--hence as summer's "herald"), since Ynglinga saga states one of the great festivals of the calendar is celebrated at sumri, þat var sigrblót "in summer, for victory"; Odin is consistently referred to throughout the Norse mythos as the bringer of victory. The Ynglinga saga also details the sacrifices made by the Swedish king Aun, to whom it was revealed that he would lengthen his life by sacrificing one of his sons every ten years; nine of his ten sons died this way. When he was about to sacrifice his last son Egil, the Swedes stopped him.

Eddic

According to the Prose Edda, Odin, the first and most powerful of the Aesir, was a son of Bestla and Borr and brother of Ve and Vili. With these brothers, he cast down the frost giant Ymir and made Earth from Ymir's body. The three brothers are often mentioned together. "Wille" is the German word for "will" (English), "Weh" is the German word (Gothic wai) for "woe" (English: great sorrow, grief, misery) but is more likely related to the archaic German "Wei" meaning 'sacred'.

Odin had several wives, with whom he fathered many children. With his first wife, Frigg, he fathered his most gentle son Balder, who stood for happiness, goodness, wisdom, and beauty. He also fathered the blind god Hod, who was representative of darkness (in contrast to Balder's light). Frigg is best known for her love of her son Balder, as well as the story of how she travelled Earth in order to protect him from fated death. By the Earth Goddess Jord (Fjorgin) Odin was the father of his most famous son, Thor the Thunderer. By the giantess Grid, Odin was the father of Vídar, and by Rinda he was father of Váli. Also, many royal families claimed descent from Odin through other sons. For traditions about Odin's offspring, see Sons of Odin.

According to the Hávamál Edda, Odin was also the creator of the Runic alphabet. It is possible that the legends and genealogies mentioning Odin originated in a real, prehistoric Germanic chieftain who was subsequently deified; but this is presently impossible to prove or disprove.

Exploits

Odin and his brothers, Vili and Ve, are attributed with slaying Ymir, the Ancient Giant, to form Midgard. From Ymir's flesh, the brothers made the earth, and from his shattered bones and teeth they made the rocks and stones. From Ymir's blood, they made the rivers and lakes. Ymir's skull was made into the sky, secured at four points by four dwarfs named East, West, North, and South. From Ymir's brains, the three Gods shaped the clouds, whereas Ymir's eye-brows became a barrier between Jotunheim (giant's home) and Midgard, the place where men now dwell. Odin and his brothers are also attributed with making humans.

After having made earth from Ymir's flesh, the three brothers came across two logs (or an ash and an elm tree). Odin gave them breath and life; Vili gave them brains and feelings; and Ve gave them hearing and sight. The first man was Ask and the first woman was Embla and from them all human families are descended. Many kings and royal houses claim to trace their lineage back to Odin through Ask and Embla.

Odin ventured to Mímir's Well, near Jötunheim, the land of the giants; not as Odin, but as Vegtam the Wanderer, clothed in a dark blue cloak and carrying a traveller's staff. To drink from the Well of Wisdom, Odin had to sacrifice his left eye, symbolizing his willingness to gain the knowledge of the past, present and future. As he drank, he saw all the sorrows and troubles that would fall upon men and the gods. He also saw why the sorrow and troubles had to come to men.

Mímir accepted Odin's eye and it sits today at the bottom of the Well of Wisdom as a sign that the father of the gods had paid the price for wisdom. Sacrifice for the greater good is a recurring theme in Norse mythology, as in the case of Tyr, who sacrificed his hand to fetter Fenrisulfr.

Odin was said to have learned the mysteries of seid from the Vanic goddess and völva Freyja, despite the unwarriorly connotations of using magic. In Lokasenna, Loki derides Odin for practicing seid, implying it was women's work. Another example of this may be found in the Ynglinga saga where Snorri opines that men who used seid were ergi or unmanly.

Odin's quest for wisdom can also be seen in his work as a farmhand for a summer, for Baugi, and his seduction of Gunnlod in order to obtain the mead of poetry. (See Fjalar and Galar for more details.)

In the Rúnatal, a section of the Hávamál, Odin is attributed with discovering runes. He was hung from the tree called Yggdrasill while pierced by his own javelin for nine days and nights, in order to learn the wisdom that would give him power in the nine worlds. Nine is a significant number in Norse magical practice (there were, for example, nine realms of existence), thereby learning nine (later eighteen) magical songs and eighteen magical runes.

Some scholars hypothesize that this legend influenced the story of Christ's crucifixion. It is also similar to the story of Buddha's enlightenment. In Shamanism, the traversal of the axis mundi by the shaman to bring back knowledge is a common pattern. We know that sacrifices, human or otherwise, to the gods were commonly hung in or from trees, often transfixed by spears. (See also: Peijainen) Additionally, one of Odin's names is Ygg, and the Norse name for the World Ash —Yggdrasill—therefore means "Ygg's (Odin's) horse". Another of Odin's names is Hangatýr, the god of the hanged.

Attributes

Odin had three residences in Asgard. First was Gladsheim, a vast hall where he presided over the twelve Diar or Judges, whom he had appointed to regulate the affairs of Asgard. Second, Valaskjálf, built of solid silver, in which there was an elevated place, Hlidskjalf, from his throne on which he could perceive all that passed throughout the whole earth. Third was Valhalla (the hall of the fallen), where Odin received the souls of the warriors killed in battle, called the Einheriar. The souls of women warriors, and those strong and beautiful women whom Odin favored, became Valkyries, who gather the souls of warriors fallen in battle (the Einheriar), as these would be needed to fight for him in the battle of Ragnarök. They took the souls of the warriors to Valhalla. Valhalla has five hundred and forty gates, and a vast hall of gold, hung around with golden shields, and spears and coats of mail.

Odin has a number of magical artifacts associated with him: the dwarven javelin Gungnir, which never misses its target; a magical gold ring (Draupnir), from which every ninth night eight new rings appear; and two ravens Huginn and Muninn (Thought and Memory), who fly around Earth daily and report the happenings of the world to Odin in Valhalla at night. He also owned Sleipnir, an octopedal horse, who was given to Odin by Loki, and the severed head of Mímir, which foretold the future. He also commands a pair of wolves named Geri and Freki, to whom he gives his food in Valhalla since he consumes nothing but mead or wine. From his throne, Hlidskjalf (located in Valaskjalf), Odin could see everything that occurred in the universe.

The Valknut (slain warrior's knot) is a symbol associated with Odin. It consists of three interlaced triangles.

Names

The Norsemen gave Odin many nick-names; this was in the Norse skaldic tradition of heiti and kennings, a poetic method of indirect reference, as in a riddle. The name Alföðr ("Allfather", "father of all") appears in Snorri Sturluson's Younger Edda. (It probably originally denoted Tiwaz, as it fits the pattern of referring to Sky Fathers as "father".) According to Bernhard Severin Ingemann, Odin is known in Wendish mythology as Woda or Waidawut.

Persisting beliefs in Odin

Snorri Sturluson feels compelled to give a rational account of the Aesir in his preface. In this scenario, Snorri speculates that Odin and his peers were originally refugees from the Anatolian city of Troy, etymologizing Aesir as derived from the word Asia. Some scholars believe that Snorri's version of Norse mythology is an attempt to mould a more shamanistic tradition into a Nordic mythological cast. In any case, Snorri's writing (particularly in Heimskringla) tries to maintain an essentially scholastic neutrality. That Snorri was correct was one of the last of Thor Heyerdahl's archeoanthropological theories (see The search for Odin).

The spread of Christianity was slow in Scandinavia, and it worked its way downwards from the nobility. Among commoners, beliefs in Odin may have lingered for some time, and legends would be told until modern times.

The last battle where Scandinavians attributed a victory to Odin was the Battle of Lena in 1208.[2] The former Swedish king Sverker had arrived with a large Danish army, and the Swedes led by their new king Eric were outnumbered. Odin then appeared riding on Sleipnir and he positioned himself in front of the Swedish battle formation. He led the Swedish charge and gave them victory.

The bagler-saga, written in the thirteenth century concerning events in the first two decades of the thirteenth century, tells a story of a one-eyed rider with a broad-brimmed hat and a blue coat who asks a smith to shoe his horse. The suspicious smith asks where the stranger stayed during the previous night. The stranger mentions places so distant that the smith does not believe him. The stranger says that he has stayed for a long time in the north and taken part in many battles, but now he is going to Sweden. When the horse is shod, the rider mounts his horse and says "I am Odin" to the stunned smith, and rides away. The next day, the battle of Lena took place. The context of this tale in the saga is that a peace-treaty has been signed in Norway, and Odin, a god of war, no longer has a place there. Håkon Håkonssons saga, written in the 1260s, describes how, at some point in the 1230s, Skule Baardsson has the skald Snorri Sturluson compose a poem comparing one of Skule's enemies to Odin, describing them both as bringers of strife and disagreement. These episodes do not necessarily imply a continued belief in Odin as a god, but show clearly that his name was still widely known at this time.

Scandinavian folklore also maintained a belief in Odin as the leader of the Wild Hunt (Åsgårdsreia in Norwegian). His main objective seems to have been to track down and kill the forest dweller huldran or skogsrået. In these accounts, Odin was typically a lone hunter, save for his two wolves. Originally, he was armed with a javelin, but in later accounts this was sometimes changed to a rifle [citation needed].

Toponyms with the name of Odin

Many toponyms ("place names") in Northern Europe where Germanic Tribes existed contain the name of *Wodanaz (Norse Odin, West Germanic Woden).

Modern age

Germanic neopaganism

Odin, along with the other Germanic Gods and Goddesses, is recognized by Germanic neopagans. His Norse form is particularly acknowledged in Ásatrú, the "faith in the Aesir", an officially recognized religion in Iceland, Denmark, Norway and Sweden.

Modern popular culture

With the Romantic Viking revival of the early-to-mid nineteenth century, Odin's popularity increased again. Wotan (Odin) is one of the main protagonists of Richard Wagner's opera cycle, Der Ring des Nibelungen. This depiction in particular has had influence on many subsequent fiction writers and has since resulted in varying references and allusions in multiple types of media.

Literature

- H. R. Ellis Davidson, The Battle God of the Vikings, York (1972)

- Hector Chadwick, The Cult of Othinn

- L. Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Pratt The Incomplete Enchanter Henry Holt and Company (1941) and several reprints in paperback

- Kris Kershaw, Odin, 2004, ISBN

- Horst Obleser, Odin, 1993, ISBN-X

- Grenville Pigott, A Manual to Scandinavian Mythology, 2001, ISBN

- Padraic Colum, Nordic Gods and Heroes, 1996, ISBN

- Peter Sawyer, The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings, 1997, ISBN

- Neil Philip, The Illustrated Book of Myths, 1995, ISBN

- Snorri Sturlson, Prose Edda Jean I. Young, trans. 2002, ISBN

- ____. Poetic Edda, Carolyne Larrington, trans. 1999, ISBN

- Sverre Bagge, "Society and Politics in Snorri Sturluson's Heimskringla", 1991, ISBN

- Daniel James, "Ragnorok, Odin, and Troy", 2007

- George "Maddox" Ouzounian, "The Alphabet of Manliness", 2006, ISBN

- Douglas Adams, "The Long Dark Tea-Time of the Soul", 1988, ISBN 0-434-00921-0

See also

References

- ^ Skaldskaparmal, in Edda. Anthony Faulkes, Trans., Ed. (London: Everyman, 1996).

- ^ [1]

External links

- A. Asbjorn Jon's "Shamanism and the Image of the Teutonic Deity, Óðinn"

- Viktor Rydberg's "Teutonic Mythology: Gods and Goddesses of the Northland" e-book

- W. Wagner's "Asgard and the Home of the Gods" e-book

- "Myths of Northern Lands" e-book by H.A. Guerber

- Peter Andreas Munch's "Norse Mythology: Legends of Gods and Heroes" e-book