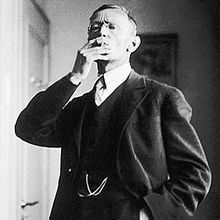

Hermann Hesse

Hermann Karl Hesse , pseudonym : Emil Sinclair (* July 2, 1877 in Calw ; † August 9, 1962 in Montagnola , Switzerland ; resident in Basel and Bern ), was a German-Swiss writer , poet and painter . He gained fame with prose works such as Siddhartha or Der Steppenwolf and with his poems (e.g. stages ). In 1946 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature and in 1954 the Order Pour le Mérite for Sciences and Arts .

As the son of a Wuerttemberg missionary daughter and a German-Baltic missionary, Hesse was a citizen of the Russian Empire by birth . From 1883 to 1890 and again from 1924 he had Swiss citizenship , in between he was a citizen of Württemberg .

Life

Childhood and Adolescence (1877–1895)

The birth room is behind the first two windows on the left on the second floor (upper row of five windows).

parents house

Hermann Hesse came from a Protestant missionary family and grew up in a sheltered and intellectual family atmosphere. Both parents worked on behalf of the Basel Mission in India , where Hesse's mother, Marie Gundert (1842–1902) from Württemberg , was also born. His father Johannes Hesse (1847–1916), son of a district doctor and state councilor and grandson of a merchant who emigrated from Lübeck to Estonia , lived in Weißenstein in what was then the Russian Empire ; thus Hermann was also a Russian citizen from birth . In Calw , Johannes Hesse had worked for the Calwer publishing association since 1873 . Its board member was his father-in-law Hermann Gundert (1814-1892), whom he followed from 1893 to 1905 as board member and publisher.

Hermann Hesse had eight siblings, three of whom died in infancy. He grew up with the two years older half-brothers Theodore and Karl Isenberg, children of his mother with her late first husband Charles Isenberg . The other three full siblings were Adele, Marulla and Hans Hesse. Hermann Hesse was an imaginative child with an expressive temperament. His talent made itself felt at an early age: he had no shortage of poetry ideas and he drew wonderful pictures. His mother wrote in a letter to his father Johannes Hesse on August 2, 1881:

"[...] the fellow has a life, a huge strength, a powerful will and really a kind of amazing mind for his four years. Where are you going? This inner struggle against his high tyrannical

spirit , his passionate storming and urging [...] God has to put this proud mind into work, then something noble and splendid will come of it, but I shudder at the thought of what wrong or weak upbringing of this passionate young person. "

The world in which Hermann Hesse spent the first years of his life was on the one hand shaped by the spirit of Swabian Pietism . On the other hand, his childhood and youth were shaped by his father's Balticism, which Hermann Hesse described as "an important and effective fact". In Wuerttemberg as well as in Switzerland , the father was an unadapted stranger who never took root anywhere and always seemed like a very polite, very strange and lonely, little understood guest. In addition, the maternal family also belonged to the largely international community of missionaries, and that his grandmother, Julie Gundert, born in this line, came from this line. Dubois (1809–1885), a French-speaking Swiss woman, also remained a stranger in the Swabian petty-bourgeois world throughout her life.

In his early tanners , Hesse had experiences and incidents from his childhood and youth in Calw, the atmosphere and adventures on the river, the bridge, the chapel, the closely spaced houses, hidden nooks and crannies as well as the residents with all their lovable peculiarities or quirks -Narrations described and brought to life. In Hesse's youth, this atmosphere was, among other things, strongly influenced by the long-established guild of tanners . Hesse often and gladly stayed on the Nikolausbrücke, his favorite place in Calw. This is why the life-size Hesse sculpture created by Tassotti , shown below , was installed there in 2002.

A counterweight to pietism that worked more from within was the world of Estonia, which repeatedly emerged in the stories of his father Johannes Hesse. "An extremely cheerful, with all Christianity, very lively world [...] we wished nothing more than to see this Estonia [...], where life was so heavenly, so colorful and funny."

In addition, Hermann Hesse had access to the extensive library of his learned grandfather Hermann Gundert with works of world literature, which he studied intensively. All these components of cosmopolitanism "were the foundations for isolation and for a security against any nationalism that was decisive in my life".

School education

In 1881 the family moved to Basel for five years . In 1882, his father Johannes acquired Basel citizenship, which made the entire family Swiss citizens. From 1885 Hesse was a student in the boarding school called Knabenhaus der Mission. Hermann Hesse's father taught in the “Basel Mission”. In July 1886 the family moved back to Calw, where Hesse first entered the second class of the Calw Latin School (Reallyzeum). In 1890 he switched to the Latin school in Göppingen to prepare for the Württemberg state examination , which allowed Württemberg people to train as state officials or pastors free of charge . Therefore, in November 1890, his father became the only member of the family to acquire citizenship of Württemberg, which meant that he lost Swiss citizenship . After he had passed the state examination in Stuttgart in 1891, he attended the Protestant-theological seminar in Maulbronn Monastery , intended for a theological career . In Maulbronn in March 1892, the student's “rebellious” character became apparent: he escaped from the seminar because he wanted to become “either a poet or nothing at all” and was only picked up in the open a day later.

Now, accompanied by violent conflicts with the parents, an odyssey through various institutions and schools began. At the age of 14, Hermann Hesse was probably in a depressive phase and expressed suicidal thoughts in a letter dated March 20, 1892 ("I want to go there like the sunset"). In May 1892, the youth attempted suicide with a revolver in the Bad Boll asylum run by the theologian and pastor Christoph Friedrich Blumhardt . Subsequently, Hesse was brought by his parents to the mental hospital in what was then Stetten im Remstal (today's Diakonie Stetten eV in Kernen im Remstal ) near Stuttgart, where he had to work in the garden and help teach mentally handicapped children.

This is where pubescent defiance, loneliness and the feeling of being misunderstood by his family culminated. In the famous accusing letter of September 14, 1892 to his father, he titled this, now clearly taking a distance, with "Dear Sir!" - this in contrast to earlier, partly open, very communicative letters. He also provided the letter text with aggressive, ironic and sarcastic formulations. So he (in addition to himself) also assigned his father to be responsible for possible future “crimes” that he, Hermann, could commit as a “world hater” as a result of his stay in Stetten. Finally he signed as “H. Hesse, prisoner in the prison in Stetten ”. In the postscript he added: “I am starting to think about who is moronic in this affair.” He felt abandoned by God, his parents and the world and saw only hypocrisy behind the rigid pietistic-religious traditions of the family.

From the end of 1892 he was able to attend grammar school in Cannstatt . In 1893 he passed the one-year exam there , but dropped out of school.

Teaching

After he had escaped his first apprenticeship as a bookseller in Esslingen am Neckar after three days, Hesse began an apprenticeship as a mechanic in the Perrot tower clock factory in Calw for 14 months in the early summer of 1894. The monotonous work of soldering and filing soon reinforced his desire to return to literature and intellectual debate. In October 1895 he was ready to begin a new apprenticeship as a bookseller in Tübingen and to pursue it seriously. He later processed the experiences of his youth in his novel Unterm Rad .

The path to becoming a writer (1895–1904)

As a ten-year-old, Hesse had tried a fairy tale: The two brothers . It was published in 1951.

Tübingen

From October 17, 1895, Hesse worked in the Heckenhauer bookstore and antiquarian bookshop in Tübingen . The focus of the range consisted of theology , philology and law . His duties as an apprentice included checking ( collating ), packing, sorting and archiving the books. At the end of each 12-hour working day, Hesse took up further private education, books also compensated for a lack of social contact on the long, work-free Sundays. In addition to theological writings, Hesse read in particular Goethe , later Lessing , Schiller and texts on Greek mythology . In 1896 his poem Madonna was printed in a magazine published in Vienna, and more followed in later editions of the Deutsches Dichterheim (organ for poetry and criticism) . The bookseller apprentice Hesse made friends in 1897 with the then law student and later doctor and writer Ludwig Finckh from Reutlingen , who was to follow Hesse to Gaienhofen after his doctorate in 1905 .

After completing his apprenticeship in October 1898, Hesse initially worked as a sales assistant in the Heckenhauer bookstore with an income that ensured him financial independence from his parents. At that time he read works from the German Romantic period, especially Novalis , Clemens Brentano , Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff and Ludwig Tieck . In letters to his parents, he expressed his conviction that "for artists morality is replaced by aesthetics". While still a bookseller, Hesse published his first book in the fall of 1898, the small volume of poems, Romantic Songs , and in the summer of 1899 the prose collection An Hour Behind Midnight . Both works were a business failure. Of the romantic songs , only 54 copies of the total print run of 600 were sold within two years, even an hour after midnight , only 600 copies were printed and sold slowly. The Leipzig publisher Eugen Diederichs , however, was convinced of the literary quality of the works and saw the publication from the beginning more as a promotion of the young author than as a profitable business.

Basel

From autumn 1899 Hesse worked in the Reich'schen Buchhandlung, a respected second-hand bookshop in Basel. Since his parents were in close contact with scholarly families in Basel, a spiritual and artistic cosmos opened up for him with the richest stimuli. At the same time, Basel also offered the loner many opportunities to retreat into private experiences on larger journeys and hikes that served artistic self-exploration and on which he repeatedly tried out the ability to put sensual experiences in writing. In 1900 Hesse was exempted from military service because of his poor eyesight. The eye ailment lasted all his life, as did nerve pain and headache. In the same year, his book Hermann Lauscher was published - initially under a pseudonym.

Hesse had a warm relationship with Rudolf Wackernagel, who lived in Riehen , and his wife.

After Hesse quit his position in the R. Reich bookstore at the end of January 1901, he was able to fulfill a great dream and travel to Italy for the first time, where he spent March to May in the cities of Milan , Genoa , Florence , Bologna , Ravenna and Padua and stopped Venice . In August of the same year he moved to a new employer, the antiquarian Wattenwyl in Basel. At the same time he had more and more opportunities to publish poems and short literary texts in magazines. Now fees from these publications also contributed to his income. Richard von Schaukal made Hesse public as the author of the Lauscher in 1902 . In 1903, Hesse met the Basel photographer Maria Bernoulli , known as "Mia", who was nine years his senior . Together they traveled to Italy (second trip to Italy) and married the following year.

His first publications include the novels Peter Camenzind (1904) and Unterm Rad (1906), in which Hesse thematized the conflict between spirit and nature that would later permeate his entire work. His literary breakthrough came with the civilization-critical development novel Peter Camenzind , which was published for the first time in 1903 as a preprint and in 1904 by the publisher S. Fischer. This success allowed him to marry and settle down as a freelance writer on Lake Constance. Hesse was in Basel for the last time in 1930.

Between Lake Constance, India and Bern (1904–1914)

In August 1904 Hesse married the independent Basel photographer Maria Bernoulli (1868–1963), who came from the extensive Bernoulli family. The three sons Bruno (1905–1999, painter, graphic artist), Hans Heinrich (called Heiner , 1909–2003, decorator) and Martin (1911–1968, photographer) emerged from this marriage. In keeping with the lifestyle reform , he and Maria moved to the then very remote Baden village of Gaienhofen on Lake Constance and rented a simple farmhouse without running water or electricity, in which they lived for three years. In 1907 they had a friend from Basel architect Hans Hindermann build a reform-style country house in the village , which they could move into that same year. There they created a large garden for self-sufficiency. Hesse often went on trips alone, while Maria and the children continued to live in the large house with a garden.

In Gaienhofen, Hesse met his friends Othmar Schoeck , Volkmar Andreae and Fritz Brun through the Constance dentist and composer Alfred Schlenker (1876–1950) . In 1906 Eduard Zimmermann created a bust for Hesse.

In 1906 he was co-editor of the March magazine published by Albert Langen , with which he stayed until 1912. Also in 1906, Hesse's second novel, Unterm Rad , appeared, which he had written in Calw. In it, Hesse processed his experiences from school and training. In April 1907, Hesse stayed for a cure in Locarno and as a guest in the life reform colony on Monte Verità near Ascona. The stories In den Felsen , Freunde and the legends from Thebais tell of his hermit existence . After his return from Ascona, he tried to adapt to bourgeois life again. His next novel Gertrud from 1910, however, showed Hesse in a creative crisis - he had a hard struggle with this work, in later years he considered it a failure. Hesse was also friends with Ernst Morgenthaler , who portrayed Hesse, and Wilhelm Schäfer , who dedicated the book Karl Stauffer's Life Course - A Chronicle of Passion to him in 1912 .

In April / May 1911, Hesse went on a trip to Umbria with Fritz Brun and a few other Swiss friends.

In Hesse's marriage, the dissonances had increased since 1910. In order to gain some distance in his creative crisis, Hesse and Hans Sturzenegger set off on a long journey to Ceylon and India in 1911 . He did not find the spiritual and religious inspiration he had hoped for there, but the trip still had a strong influence on his other literary work and was initially reflected in the publication Aus India in 1913 . After Hesse's return from Asia, he sold his house in Gaienhofen in 1912. In late summer the family moved to an old country house on the outskirts of Bern ; before Hesse his friend Albert Welti had rented it. But even this change of location could not solve the marriage problems, as Hesse described in his novel Roßhalde in 1914 . Mental crises in both of them - Maria Bernoulli was treated in the sanatorium of Theodor Brunner in Küsnacht in 1919 - later led to a final falling apart and in 1923 to a divorce. After the parents separated in 1919, the children were distributed. At the age of 15, Bruno was cared for by his father by the Cuno Amiet family of painters . Heiner stayed with his mother while Martin came to the Ringier family in Kirchdorf as a foster child.

As his "best and most loyal friend" during his years in Bern, Hesse described the forest scientist Walter Schädelin .

Upheaval caused by the First World War (1914-1919)

Prisoner of War Welfare

When the First World War broke out in 1914, Hesse, at that time still an advocate of the so-called “ Ideas of 1914 ”, reported to the German embassy as a volunteer . However, he was found unfit and assigned to the German embassy in Bern, where he set up the "Book Center for German Prisoners of War", which supplied soldiers interned in foreign camps with reading through the German prisoner-of-war organization until 1919. In this context, Hesse was henceforth busy collecting and sending books for German prisoners of war. During this time he was co-editor of the Deutsche Interniertenzeitung (1916/17), publisher of the Sunday messenger for German prisoners of war (1916-1919) and responsible for the “library for German prisoners of war”.

Political disputes

On November 3, 1914, he published the article O Friends, Not These Tones in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung , in which he appealed to German intellectuals not to lapse into nationalist polemics. What followed was what Hesse later described as a major turning point in his life: for the first time he found himself in the midst of a violent political dispute, the German press attacked him, he received hate mail and old friends broke up with him. He also received approval from his friend Theodor Heuss , who later became the first Federal President of the Federal Republic of Germany, but also from the French writer Romain Rolland , who visited Hesse in August 1915.

Family blows of fate

These conflicts with the German public had not yet subsided when Hesse was plunged into an even deeper life crisis due to a series of blows of fate: his father's death on March 8, 1916, the serious illness ( meningitis ) of his son Martin, who was three at the time, and the Breaking marriage with Maria Bernoulli. Hesse had to interrupt his service in prisoner welfare and seek psychiatric treatment , during which he also made his first experiences with psychoanalysis . He seriously considered risking the “break with home, position, family” and moving to Ascona, where he had Gustav Gamper buy a house for him.

War opponents and dropouts

Through the experience of the World War, Hesse had become a decided opponent and supporter of refusal . In September / October 1917, Hesse wrote his novel Demian in a three-week work frenzy , the second part a reflection of his time on Monte Verità. The book was published after the end of the war in 1919 under the pseudonym Emil Sinclair, "so as not to scare off the youth with the familiar name of an old uncle". But also, as Hesse wrote in a letter to Eduard Korrodi , because "who wrote this poem [...] was not Hesse", "the author of so many books, but a different person who had experienced new things and was approaching new things". As a contemporary witness, Thomas Mann said: “The electrifying effect” of Demian is unforgettable, “a poem that hit the nerve of the times with uncanny accuracy and a youth who believed that a herald of their deepest life emerged from among them (during it was already a forty-two year old who gave them what they needed), carried away to grateful delight. ”In 1918 Hermann Hesse's cousin, Pastor Carl Immanuel Philipp Hesse , was killed as a civilian victim of the Estonian War of Independence . Hesse got involved with the emigrants, whom he generously supported. His and Albert Ehrenstein's interventions prevented Eduard Claudius' expulsion during the Second World War .

New home in Ticino (1919–1962)

Casa Camuzzi

When Hesse was able to resume his civil life in 1919, his marriage was broken. His wife Mia (Maria) fled to Ascona in autumn 1918, where her depression broke out in full. But even after her healing, Hesse saw no future together with her. The apartment in Bern was closed and the three boys were temporarily housed with friends, the eldest son Bruno with his painter friend Cuno Amiet . The experience and the oppressive burden of having left his family were dealt with by Hesse in his story Klein and Wagner , published in 1919, about the civil servant Klein, who broke out of his bourgeois life for fear of going insane and, like the teacher Wagner, of killing his family flees to Italy.

Hesse moved to Ticino alone in mid-April 1919 . He first lived in a small farmhouse at the entrance to Minusio near Locarno and then on April 25th moved to Sorengo above Lake Muzzaner in simple accommodation that was arranged for him by his musician friend Volkmar Andreae , with whom he had been friends since around 1905 was. But then on May 11, 1919, he rented four small rooms in a castle-like building, the " Casa Camuzzi ", in Montagnola , a higher village to the southwest and not far from Lugano neo-baroque palazzos. From this hillside location ("Klingsor's balcony") and above the densely overgrown forest property, Hesse overlooked Lake Lugano to the east with the opposite slopes and mountains on the Italian side. The new living situation and the location of the building inspired Hesse not only to take up new literary activities, but also to compensate and supplement other sketched drawings and watercolors, which was clearly reflected in his next great story by Klingsor, last summer of 1920. In December 1920, Hesse met Hugo Ball and his wife Emmy Hennings , also in Ticino .

In 1922, Hesse's novel Siddhartha was published . This expressed his love for Indian culture and for Asian wisdom teachings, which he had already got to know at home. Hesse gave the main character of his "Indian poetry" the first name of the historical Buddha , Siddhartha . His then lover Ruth Wenger (1897–1994) inspired him to write the character in the novel, Kamala, who teaches Siddhartha love in this Indian poem. Henry Miller said: “A book whose depth is hidden in the artfully simple and clear language, a clarity that presumably throws the mental numbness of those literary philistines who always know so well what is good and what is bad literature. To create a Buddha that surpasses the generally recognized Buddha is an unheard of act, especially for a German. For me, Siddhartha is a more effective medicine than the New Testament. "

In May 1924, Hesse was granted citizenship of the city of Bern and thus for the second time Swiss citizenship . In doing so, he gave up the German citizenship that he had acquired in 1890 with a view to the upcoming state examination in Göppingen. After divorcing his first wife Maria, on January 11, 1924, Hesse finally married Ruth Wenger, the daughter of the Swiss writer Lisa Wenger . Hesse's second marriage, however, was doomed to failure from the outset due to completely different life needs and goals, despite erotic attraction and similar cultural interests, and was divorced three years later on April 24, 1927 at the request of his wife.

His next larger works, Kurgast from 1925 and Die Nürnberger Reise from 1927, are autobiographical stories with an ironic undertone. In them, Hesse's most successful novel, Der Steppenwolf from 1927, was announced, which for him presented itself as “a fearful warning call” before the coming World War and was appropriately schooled or ridiculed by the German public of that time. On his 50th birthday, which he celebrated that same year, the first biography of Hesse by his friend Hugo Ball was published.

Shortly after the new successful novel, Hesse experienced a turning point through the relationship with Ninon Dolbin geb. Ausländer (1895–1966), his future - third - wife, who came from Czernowitz in Bukowina , was an art historian and had established a constant correspondence with him as a 14-year-old student. He spent extended winter holidays with Dolbin in Arosa in 1928 and 1929 , where he also met Hans Roelli . In 1928 Hesse undertook trips to Ulm , Heilbronn , Würzburg (March 22nd), Darmstadt and Berlin . In 1930 the story Narcissus and Goldmund appeared . Hermann Hesse also dedicated a fairy tale to each of his three wives: his first wife Mia the fairy tale Iris (1916), Pictors Metamorphoses (1922) Ruth Wenger, and shortly after marrying Ninon Dolbin in March 1933, his last and very autobiographical fairy tale Vogel was written , identical to the name with which he signed private notes and letters to Ninon and with which she often addressed him.

Casa Hesse (Casa Rossa)

In 1931, Hesse left the rented apartment in Casa Camuzzi and moved with his new partner, with whom he had his third marriage on November 14th, into a larger house, Casa Hesse , also called Casa Rossa because of the reddish paint on the outside . The building was built according to Hesse's wishes, financed by his friend Hans Conrad Bodmer . The property was above and at the southern end of Montagnola, within sight of Casa Camuzzi and only ten minutes' walk from it. The land and the building were made permanently available to Hesse by Bodmer, and after his death to Ninon for life.

From the school center at the central local car park of Montagnola, the path leads past the playground behind the school to the wrought-iron garden portal of the house on Via Hermann Hesse . The access road leads in a slight increase parallel to the slope into the property, on the most exposed point of which a kind of two-storey double house was built. Each of the two parts has a separate entrance with its own staircase; On the ground floor and first floor, both parts are connected to each other via the corridors and adjacent rooms. For reasons of the daily rhythm, but also for organizational reasons and reasons of different usage, Hesse and his wife attached importance to a certain separation of the rooms: the larger, south-western part with kitchen, dining room, library, guest room, bedroom (N.), bathroom ( N.) and side rooms were mainly used by Ninon; the north-eastern section was Hermann Hesse's area of activity with a studio, work room, bedroom (H.), bathroom (H.) and ancillary areas. The library on the ground floor served both as a reception room for the large number of guests, as well as a living, reading and music room with a wide view of Monte Generoso to the south-east , and had a direct connection to the studio.

The studio to the north-east of the library was the multifunctional room of the house, in which Hesse conducted his extensive correspondence with a typewriter, then it functioned as a warehouse for packaging material for the large number of mail and books that Hesse made ready for dispatch himself. In this room, however, he also pursued his hobby , watercolor painting , when he was not painting in front of nature, which usually happened. He kept painting and art utensils there as well as other book collections. However, Hesse generally kept his work area upstairs with special books hidden from guests and did not want to be disturbed by family members there either. Similar to the Casa Camuzzi, Hesse also had a north-east facing, wide view over Lake Lugano into the eastern Seetal right into the Italian slopes and mountain ranges. Many of his watercolors bear witness to this house, its garden, the near and far surroundings and the extensive views of the Ticino landscape.

Hesse's extensive correspondence brought his publishers Samuel Fischer , Gottfried Bermann Fischer , Peter Suhrkamp and Siegfried Unseld here. Not only Thomas Mann , but also the Mann family were received here several times. Friendships like the one with Romain Rolland were deepened here, and colleagues like Bertolt Brecht , Max Brod , Martin Buber , Hans Carossa , André Gide , Annette Kolb , Jakob Wassermann and Stefan Zweig found their way to Montagnola. In addition, Hermann Hesse was at times more closely related to musicians such as Adolf Busch , Edwin Fischer , Eugen d'Albert , his friend Theodor W. Adorno and especially friendly to the composer he admired, Othmar Schoeck , of whom (the only one) Hesse had the feeling that he really set his poems to music adequately. Hesse himself had an intense relationship with music, which can be seen in his poems, but is also thematized in prose works such as Das Glasperlenspiel , Steppenwolf and Gertrud .

Two years later, after Hesse had moved from Casa Camuzzi to Casa Rossa , the young Gunter Böhmer visited Hermann Hesse in April 1933 and settled in Casa Camuzzi . Ten years later, in 1943, the painter Hans Purrmann , a student of Henri Matisse , moved to Montagnola and some time later also moved to Casa Camuzzi. Hesse had a delightful friendship with both painters and draftsmen. Böhmer supported Hesse in his efforts to acquire artistic techniques and the laws of different perspective representations .

The former Casa Hesse fell back to the Bodmer family after Hesse and Ninon's death. It was sold, the color and the rear side of the terrace also redesigned by the new owner. Today (as of 2006) it is privately owned and cannot be visited. A path, in the extension of Via Hermann Hesse below the property, allows a view of the south side of the house and the slope, which inspired Hesse to give a series of descriptions of his gardening activities.

The glass bead player

Photo by Carl van Vechten . The Casa Rossa was one of the contact points for Thomas Mann and several other emigrants from Germany on their way into exile.

In 1931 he began drafting his last great work, which was to be titled Das Glasperlenspiel . In 1932 he published the story Die Morgenlandfahrt as a preliminary to this . As in the Morgenlandfahrt , the actual basic theme in the Glasperlenspiel is the discipleship of a friend and master - known as Leo or music master, rainmaker, yogin or confessor - whom Hermann Hesse is leaving and to whom he ruefully wants to return as a "servant". Hesse's political stance at this time was strongly influenced by a culture of pessimism critical of civilization:

“My friends and enemies have long known and criticized it: I don't enjoy many things and don't believe in many things that are the pride of mankind today; I do not believe in technology, I do not believe in the idea of progress, not even in democracy, I do not believe in the glory and unsurpassability of our time, nor in any of its highly paid leaders. Nature ', have unlimited respect. "

Hesse observed the takeover of power by the National Socialists in Germany with great concern. In 1933, Bertolt Brecht and Thomas Mann stopped at Hesse on their trips into exile. In the rejection of National Socialism, Mann and Hesse were united and, despite the very different expressions of their personalities, felt connected in certain basic lines of their friendly relationship until the end. There was no such connection between Hesse and Brecht, who talked about the book burnings in Germany that year .

In his own way, Hesse tried to counteract developments in Germany: He had published book reviews in the German press for decades - now he spoke out in favor of Jewish and other authors persecuted by the National Socialists. From the mid-1930s onwards, no German newspaper dared to publish articles by Hesse. Hesse did not openly oppose the Nazi regime, and his work was not officially banned or " burned ", but since 1936 it was "undesirable". Despite the restrictions, there were always new editions. The Suhrkamp Verlag KG Berlin was able to re-issue the Knulp in 1943.

Hesse's spiritual refuge from the political conflicts and later from the horror reports of the Second World War was the work on his novel Das Glasperlenspiel , which was printed in Switzerland in 1943. Not least for this late work he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1946 : "for his inspired works, which with increasing boldness and depth embody the classical ideals of humanism and high stylistic art" (justification of the Swedish Academy, Stockholm).

Correspondence

After the Second World War, Hesse's literary productivity declined: he still wrote short stories and poems, but no longer a novel. The focus of his work increasingly shifted to his ever-increasing correspondence. As early as the 1920s, Hesse had cultivated an increasingly extensive network of friends, correspondence partners and patrons in his correspondence, who repeatedly provided him and his prisoners of war with financial and material donations in exchange for handwritten and illustrated poems, watercolors or reprints during the difficult war years support. Then there were the letters from his admirers.

After investigations by his sons Bruno and Heiner Hesse and the Hesse edition archive in Offenbach, Hesse received around 35,000 letters. Since he purposely worked without a secretariat, he answered a very large part of this mail personally; 17,000 of these reply letters have been identified. As a pronounced individualist, he felt this approach was a moral obligation. This daily use by a steady stream of letters was the price that he was able to experience his reawakened fame with a new generation of German readers who hoped for financial support, assistance and orientation from the "wise old man" in Montagnola. In response to similar inquiries about his health, his daily routine or his observations of events that were of more general interest, he worked out longer observations, which he sent out as circulars (see literature review below).

death

In December 1961, Hermann Hesse fell ill with the flu, from which he recovered only with difficulty. He had had leukemia for a long time without knowing it ; He was treated with blood transfusions in Bellinzona hospital. Hesse died of a stroke in his sleep on the night of August 9, 1962 . His wife, who was waiting for him to come to breakfast, eventually found him lifeless in his usual sleeping position. The alarmed family doctor could only determine death. Two days later he was buried with his family and friends in the Sant'Abbondio cemetery in Gentilino , where the graves of Emmy and Hugo Ball are also located. Hans Jakob Meyer designed the tombstone .

In his last poem Creaking a Kinked Branch , written down in three versions in the last week of his life, he created a symbol for approaching death.

Literary meaning

Hesse's early works were still in the tradition of the 19th century: his poetry is entirely committed to romanticism , as is the language and style of Peter Camenzind , a book that the author understood as an educational novel in the successor of the Kellerchen Grünen Heinrich . In terms of content, Hesse turned against growing industrialization and urbanization, thereby picking up a trend towards life reform and the youth movement . This neo-romantic attitude in form and content was later abandoned by Hesse. The antithetical structure of Peter Camenzind , which is shown in the juxtaposition of town and country and in the contrast between male and female, can, however, still be found in Hesse's later major works (e.g. Demian and Steppenwolf ).

The acquaintance with the theory of archetypes of the psychologist Carl Gustav Jung had a decisive influence on Hesse's work, which was first shown in the story Demian . The older friend or master who opens the way to himself for a young person became one of his central themes. The tradition of the educational novel can still be found in Demian , but in this work (as in Steppenwolf ) the action no longer takes place on the real level, but in an inner “soul landscape”.

Another essential aspect in Hesse's work is spirituality, which can be found primarily (but not only) in the story of Siddhartha . Indian wisdom, Taoism and Christian mysticism form its background. The main tendency, according to which the path to wisdom leads through the individual, is a typically Western approach that does not correspond directly to any Asian teaching, even if parallels can be found in Theravada Buddhism. Homoerotic elements in his work have been addressed on various occasions in literary studies.

All of Hesse's works contain a strong autobiographical component. It is particularly evident in Demian , in the Morgenlandfahrt , but also in Klein and Wagner and, last but not least, in Steppenwolf , which can almost be exemplary of the “novel of life crisis”. In the later work this component emerges even more clearly - in the related works Die Morgenlandfahrt and Das Glasperlenspiel Hesse condensed his basic theme in multiple variations: the relationship between a younger man and his older friend or master. Against the historical background of the National Socialist dictatorship in Germany, Hesse drew a utopia of humanity and spirit in Glasperlenspiel , but at the same time he wrote another classic Bildungsroman . Both elements are balanced in a dialectical interplay.

Last but not least, with around 3,000 book reviews, which he wrote for 60 different newspapers and magazines in the course of his life, Hesse set quality standards that were unparalleled in the area of mediation, promotion and cautious criticism. In principle, he did not review any literature that appeared to him to be bad by his standards. Like Thomas Mann , Hesse also dealt intensively with Goethe's work.

The range of his reviews ranged from smaller volumes of stories by previously unknown authors to core philosophical works from Asian cultures. These central Asian works still exist today, but they were discovered and made accessible by Hesse several decades earlier, before they became common literary, philosophical and intellectual property in the western hemisphere in the 1970s.

reception

The life-size bronze figure was created by the sculptor Kurt Tassotti from Mühlacker and cast at the art foundry Balzer in Niefern. On the occasion of the poet's 125th birthday, it was installed on the Nikolausbrücke in Calw and unveiled on June 8, 2002. The figure shows the 55-year-old Hesse on his last visit to Calw in the early 1930s. “Another characteristic feature is the somewhat stiff, very upright and usually slightly tilted backwards or sideways position of the head, which expresses a certain distance . "

Hesse's early work was largely judged positively by contemporary literary criticism.

As a result of his anti-war and anti-nationalist statements, the reception of Hesse in Germany during the two world wars was strongly influenced by the press campaigns against the author. After the two world wars, Hesse covered the need for spiritual and, in some cases, moral reorientation in part of the population, especially the younger generation. For the most part, it was therefore only "rediscovered" well after 1945.

A good ten years after Hesse had been awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature , Karlheinz Deschner wrote in his pamphlet Kitsch, Konvention und Kunst in 1957 : "The fact that Hesse has published so many devastatingly low-level verses is a regrettable lack of discipline, literary barbarism" and came also with regard to prose no more favorable judgment. In the decades that followed, parts of German literary criticism followed this assessment, with Hesse being qualified by some as a producer of epigonal and kitschy literature. Hesse's reception resembles a pendulum movement: no sooner had it reached a low point in Germany in the 1960s than an unparalleled “Hesse boom” broke out among young people in the USA, which then spread to Germany again; in particular Der Steppenwolf (after which the rock band of the same name was named) became an international bestseller and Hesse became one of the most translated and widely read German authors. Over 120 million of his books have been sold worldwide (as of early 2007). In the 1970s, Suhrkamp-Verlag published a few tapes with Hesse reciting from his works at the end of his life on phonograph records . Right from the beginning of his career, Hesse devoted himself to reading by authors and processed his peculiar experiences in this context in the unusually cheerful text “Author's Evening”.

Reception of the hippies

The writer Ken Kesey had read Hesse's mystical story Die Morgenlandfahrt with enthusiasm, in which a secret society of dreamers, poets and fantasists does not follow reason but rather the heart. Based on the story, he saw himself and the Merry Pranksters as members of the secret society and the big bus trip of 1964 across the USA as his variant of the "Morgenlandfahrt".

The German-born musician Joachim Fritz Krauledat alias John Kay had reformed his former blues band Sparrow in 1968 after reading a Hesse novel and renamed it Steppenwolf in California .

Santana , another rock band from San Francisco, named their second and highly successful album from 1970 after a term from the Hesse novel Demian , which was circulating in the band at the time. Carlos Santana: "The title Abraxas comes from a book by Hermann Hesse that Gregg, Stan and Carabello read." The relevant passage from the book is also reproduced on the record cover, but in the English translation.

A Hermann Hesse Society has been founded in Kathmandu , a city on the hippie trail .

Hermann Hesse and the present

Calw, Hesse's city of birth in the Black Forest, describes itself as the Hermann-Hesse city and uses this attribute as a claim for self-promotion. In Calw, the Hermann Hesse Museum provides information about the life and work of the city's most famous son. The Black Forest Railway from Stuttgart is to operate as the Hermann Hesse Railway beyond the current end point Weil der Stadt to Calw in 2023 .

Since 1977 the International Hermann Hesse Colloquium has been held in Calw at irregular, multi-year intervals, each with a different main topic . To this end, renowned Hesse experts from Germany and abroad will give lectures in their specialist area over two to three days. Participation in the conference is open to every citizen after registration. The program is usually accompanied alternately by setting Hesse's poems to music, other musical performances, dance and drama with topics related to or from Hesse's literature and / or by a documentary or literary film adaptation.

Similar to the Calw Colloquia, the Sils Hesse Days have been held annually since 2000 in Sils-Maria in the Swiss Engadine , three to four days in the summer half-year. The lectures and discussions are each focused on a specific topic.

In memory of Hesse, three literary prizes were named after him: the Karlsruhe Hermann Hesse Literature Prize , which has been awarded since 1957, the Calw Hermann Hesse Prize awarded by the Calw Hermann Hesse Foundation since 1990 , and the Calw Hermann Hesse Prize awarded since 2017 by the International Hermann Hesse Hesse Society in Calw awarded by the International Hermann Hesse Society .

The rock musician Udo Lindenberg feels connected to Hermann Hesse . In 2008 he published a selection of Hesse texts with Suhrkamp under the title Mein Hermann Hesse: Ein Lesebuch . His Udo Lindenberg Foundation , founded in Calw in 2006, wants to promote young lyricists and musicians with competitions and “combine Hermann Hesse's poetry with music”. Prizes are awarded every two years, including a special prize for the best Hermann Hesse setting. Every year the Hermann Hesse Festival takes place in Calw, where the winners and Udo Lindenberg perform.

Estate, archival material and edition archive

Hermann Hesse's estate is kept in the following libraries and archives:

Germany

- Berlin: Foundation Archive of the Academy of Arts

- Darmstadt: Hessian State Archives

- Düsseldorf: Heinrich Heine Institute

- Frankfurt am Main: Johann Christian Senckenberg University Library

- Marbach: German Literature Archive Marbach (archives the majority of the Hesse estate)

Switzerland

- Basel: University public library

- Bern: Swiss Literary Archives (mainly letters from and to Hesse)

- St. Gallen: Cantonal Library of St. Gallen (Vadiana)

- Solothurn: Central Library Solothurn : Hermann-Hesse-Sammlung Rosa Muggli-Isler, Kilchberg (contains dedicatory copies of books, private prints, images and correspondence)

- Zurich: ETH Library Zurich (main library of the ETHZ)

Austria

- Vienna: Literature archive of the Austrian National Library , Hermann Hesse Collection Eleonore Vondenhoff

The Hermann Hesse edition archive in Offenbach am Main was built up over several decades by the lecturer and internationally renowned Hesse editor Volker Michels , with the support of his son Heiner Hesse, among others. Although the Hesse holdings in the literary archives in Bern and Marbach are larger, the Hermann Hesse Edition Archive has the most widely accessible and functionally comprehensive documentation on the life and work of Hermann Hesse.

In the German Literature Archive in Marbach , parts of the Hesse estate can also be seen in a permanent exhibition in the Modern Literature Museum. For example there are the manuscripts or typescripts for Demian , Der Steppenwolf , Narcissus and Goldmund and Gertrud .

Hesse's estate also includes the unpublished opera libretto Romeo, written by him in 1915 for his friend Volkmar Andreae, based on Schlegel's translation of the Shakespeare drama Romeo and Juliet .

Awards and honors

Hermann Hesse's literary work has been honored with a number of literary awards, international prizes and an honorary doctorate.

- 1904: Bauernfeld Prize

- 1928: Mejstrik Prize of the Vienna Schiller Foundation

- 1936: Gottfried Keller Prize

- 1946: Goethe Prize of the City of Frankfurt am Main

- 1946: Nobel Prize in Literature for his complete works

- 1947: Honorary doctorate from the University of Bern

- 1947: Appointed honorary citizen of his hometown Calw

- 1950: Wilhelm Raabe Prize

- 1954: Pour le mérite for science and the arts

- 1955: Peace Prize of the German Book Trade for his works and reviews during the Nazi era

- 1962: Honorary citizenship of the municipality of Collina d'Oro, in which Hesse's long-term residence Montagnola is located, on July 1, 1962, a few weeks before his death

The city of Calw , in which the Hermann-Hesse-Museum is also located, named its high school and a square in the pedestrian zone after him. The railway line to Weil der Stadt will also be called Hermann-Hesse-Bahn after its planned reactivation . In Hermann Hesse's novel Unterm Rad, there are several passages in the text relating to the old railway line.

There is also a Hermann-Hesse-Platz in Bad Mingolsheim and many streets named after him throughout Germany. Several schools were also named after him.

On December 8, 1998, the asteroid (9762) Hermannhesse was named after him.

On the occasion of his 125th birthday, Deutsche Post issued a special postage stamp in 2002.

Hesse museums

- Hesse Museum Gaienhofen , Germany

- Mia and Hermann Hesse House, Gaienhofen, Germany

- Museo Hermann Hesse, Montagnola , Switzerland

- Hermann-Hesse-Museum in Hesse's hometown Calw

- Hermann Hesse cabinet in Tübingen

Works (selection)

Fonts

- In Kandy. 1912.

- Robert Aghion Part 1. Part 2. Part 3. 1913.

- The island dream. 1917.

- The journeyman locksmith. 1918.

- Hike over the mountains. 1919.

- A sonata. 1919.

- The night. 1920.

- Thoughts on Dostoevsky's “Idiot”. 1920.

Single issues

- Romantic songs. Pierson, Dresden 1899.

- An hour past midnight . Nine prose studies. Diederichs, Leipzig 1899, Munich 2019, ISBN 978-3-424-35097-5

- Left behind writings and poems by Hermann Lauscher . Reich, Basel 1900.

- Poems. Edited and introduced by Carl Busse . Grote, Berlin 1902; New edition as youth poems : Grote, Halle 1950.

- Boccaccio . Schuster & Loeffler, Berlin 1904.

- Francis of Assisi . Schuster & Loeffler, Berlin 1904.

- Peter Camenzind . Novel. Fischer, Berlin 1904.

- Under the wheel . Novel. Fischer, Berlin 1906.

- This side. Stories. Fischer, Berlin 1907; Revised and supplemented new edition ibid. 1930.

- Neighbours. Stories. Fischer, Berlin 1908.

- Gertrud . Novel. Langen, Munich 1910; Reprint: Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1955.

- Detours . Stories. Fischer, Berlin 1912; New edition supplemented as Small World : ibid. 1933.

- From India. Notes from an Indian trip. Fischer, Berlin 1913.

- Roßhalde . Novel. Fischer, Berlin 1914.

- On the way . Stories. Reuss & Itta, Constance 1915; New edition, illustrated by Louis Moilliet : Gutenberg Book Guild, Zurich 1943.

- Knulp. Three stories from Knulp's life . Narrative. Fischer, Berlin 1915.

- Music of the lonely. New poems. Salzer, Heilbronn 1915.

- The youth are beautiful . Two stories. Fischer, Berlin 1916.

- Demian . Fischer, Berlin 1919.

- Fairy tale. Fischer, Berlin 1919.

- Klingsor's last summer. Stories. Fischer, Berlin 1920 (contains: Kinderseele , Klein and Wagner and Klingsor's last summer ).

- Hike. Records. With colored pictures from the author. Fischer, Berlin 1920.

- Selected poems by S. Fischer, Berlin 1921.

- Siddhartha. An Indian seal . Fischer, Berlin 1922.

- Spa guest. Notes from a Baden cure . Fischer, Berlin 1925.

- Picture book. Descriptions. Fischer, Berlin 1926.

- The steppe wolf . Novel. Fischer, Berlin 1927.

- The Nuremberg trip . Fischer, Berlin 1927.

- Considerations. Fischer, Berlin 1928.

- Consolation of the night. New poems. Fischer, Berlin 1929.

- Narcissus and Goldmund . Narrative. Fischer, Berlin 1930.

- The Morgenlandfahrt . Narrative. Fischer, Berlin 1932.

- Storybook. Stories. Fischer, Berlin 1935.

- Hours in the garden. An idyll. Bermann-Fischer, Vienna 1936.

- Memorial sheets. Fischer, Berlin 1937.

- New poems. Fischer, Berlin 1937.

- The poems. Fretz & Wasmuth, Zurich 1942; Completed new edition: Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1953.

- The glass bead game . Novel. 2 volumes. Fretz & Wasmuth, Zurich 1943 (therein: steps ).

- Berthold. A fragment of a novel. Fretz & Wasmuth, Zurich 1945.

- Dream track. New stories and fairy tales. Fretz & Wasmuth, Zurich 1945.

- Dream track: stories and fairy tales. , 2nd edition, Manesse Verlag, Zurich 1994, ISBN 3-7175-8152-X .

- Walk in Würzburg. Edited by Franz Xaver Münzel, private print (Tschudy & Co), St. Gallen (1945).

- War and peace. Reflections on war and politics since 1914. Fretz & Wasmuth, Zurich 1946.

- Late prose. Suhrkamp, Berlin 1951.

- Letters. Suhrkamp, Berlin 1951; v. Ninon Hesse extended edition ibid. 1964.

- Incantations. Late prose - new episode. Suhrkamp, Berlin 1955.

- The late poems. Insel, Frankfurt am Main 1963 ( Insel-Bücherei , Volume 803).

- Prose from the estate. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1965 (therein: Friends ).

- The fourth biography of Josef Knecht. Two versions. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1966 ( Suhrkamp Library , Volume 181).

- The art of idleness. Short prose from the estate. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1973, ISBN 3-518-36600-9 .

Collective editions

- Collected writings in seven volumes. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1957; New edition ibid. 1978, ISBN 3-518-03108-2 .

- Collected works in twelve volumes. Compiled by Volker Michels . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1970 (= work edition edition suhrkamp ); ibid. 1987, ISBN 3-518-38100-8 .

- Collected letters in four volumes. In: Cooperation with Heiner Hesse ed. v. Ursula and Volker Michels. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1973–1986; ibid. 1990, ISBN 3-518-09813-6 .

- The art of idleness. Short prose from the estate. Edited by Volker Michels, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1973.

- The fairytales. Compiled by Volker Michels. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1975; ibid. 2006, ISBN 3-518-45812-4 .

- Volker Michels (Ed.): Hermann Hesse: Trees. Reflections and poems. With photographs by Imme Techentin. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1952; Paperback edition: Insel, Frankfurt am Main 1984, ISBN 3-458-32155-1 .

- Volker Michels (Ed.): Hermann Hesse: Music. Reflections, poems, reviews and letters. With an essay by Hermann Kasack ( Hermann Hesse's relationship to music ). Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1976. (extended edition. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1986, ISBN 3-518-37717-5 )

-

The poems 1892–1962. 2 volumes. Newly furnished and expanded with poems from the estate by Volker Michels. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1977, ISBN 3-518-36881-8 (= st 381).

- New edition in one volume: Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1992, ISBN 3-518-40455-5 .

- Also as: The Poems. Insel, Frankfurt am Main 2001, ISBN 3-458-34462-4 (= it 2762).

- Collected stories. 4 volumes. Compiled by Volker Michels. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1977. (Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1982, ISBN 3-518-03134-1 )

- Complete Works. 20 volumes and 1 register volume. Edited by Volker Michels. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 2001-2007, ISBN 978-3-518-41100-1 .

- Chris Walton, Martin Germann (eds.): Hermann Hesse and Othmar Schoeck, the correspondence. (= Schwyzer Hefte. Volume 105). Culture Commission Canton Schwyz, Schwyz 2016, ISBN 978-3-909102-67-9 .

-

The letters. 10 volumes (planned). Edited by Volker Michels. Suhrkamp, Berlin 2012 ff.

- Volume 1: 1881-1904. ISBN 978-3-518-42309-7 .

- Volume 2: 1905-1915. ISBN 978-3-518-42408-7 .

- Volume 3: 1916-1923. ISBN 978-3-518-42458-2 .

- Volume 4: 1924-1932. ISBN 978-3-518-42566-4 .

- Volume 5: 1933-1939. ISBN 978-3-518-42810-8 .

- “With the confidence that we cannot get lost in one another”. Correspondence with his sons Bruno and Heiner . Edited by Michael Limberg. Suhrkamp, Berlin 2019, ISBN 978-3-518-42905-1 .

- Justus Hermann Wetzel , letters and writings , ed. by Klaus Martin Kopitz and Nancy Tanneberger, Würzburg 2019 (pp. 79–143 correspondence with Hermann Hesse) ; ISBN 978-3-8260-7013-6

Literary films

- Die Heimkehr (2012) , German-Austrian television film based on the story of the same name.

Audio documents

- Hermann Hesse: About happiness , read by Hermann Hesse, 1949. Audio sample, in: Schweizerische Nationalphonothek Lugano, Der Hörverlag (CD46721) https://www.fonoteca.ch/cgi-bin/oecgi4.exe/inet_fnbasedetail?REC_ID=212723.011 & LNG_ID = DEU .

- Presentation of the Nobel Prize in Stockholm to Hermann Hesse, Radio DRS December 20, 1946, audio document in: Swiss National Sound Archives Lugano (DAT2614) https://www.fonoteca.ch/cgi-bin/oecgi4.exe/inet_fnbasedetail?REC_ID=614.022&LNG_ID=DEU .

Text settings based on poems (selection)

- Walther Aeschbacher : The night. Cantata for soprano and alto solo, female choir and string orchestra, with partial use of a poem by HH. Self-published, Basel 1953.

- Volkmar Andreae : Four poems by HH. for one (male) St. with a class accompaniment. Op. 23. Hug, Zurich 1912 (premiered in 1913 by Ilona Durigo in Zurich).

- Lydia Barblan-Opienska: Please. For male voice and piano. E. Barblan, Lausanne undated

- Waldemar von Baußnern : The pilgrim. For four-part male choir and organ. West German Choir Publishing House, Heidelberg 1927.

- Alfred Böckmann : moonrise. For four. Male choir. Thüringer Volksverlag, Weimar 1953 (= New Choir Song. 35 M.).

- Gerhard Bohner: Autumn. For four-part (mixed) choir. Möseler, Wolffenbüttel 1958 (= choir sheet series. Loose sheets. No. 602).

- Cesar Bresgen : Wandering for 3-part choir (1959).

- Gottfried von Eine : song cycle op.43.

- Jürg Hanselmann : Liederkreis for tenor and piano (2011), written in sand , cantata for solos, choir and orchestra (2011).

-

Bertold Hummel : 6 songs based on poems by Hermann Hesse for medium voice and piano op. 71a (1978) bertoldhummel.de .

- Kopflos A cycle of songs based on bizarre poems by Hermann Hesse for medium voice and piano, op. 108 (2002) bertoldhummel.de .

- Theophil Laitenberger : Six songs to poems by Hermann Hesse for tenor / baritone and piano (1922–1924): Spring day / Gentian blossom / Like the moaning wind / White rose in the twilight / Elegy in September / Assistono diversi santi.

- Casimir von Pászthory : 6 songs after Hesse for high or medium voice and piano.

- Günter Raphael : 8 poems op. 72 for high voice and orchestra.

- Philippine Schick : The lonely one to God. Op. 17. Cantata for dramatic soprano, lyrical baritone, three-part female choir, string orchestra and piano. Kahut, Leipzig 1929.

- Othmar Schoeck : setting of 2 dozen poems, including four poems op.8 and ten songs op.44.

- Richard Strauss : Four Last Songs (including three songs based on poems by Hesse) (1948)

- Sándor Veress : Das Glasklängespiel for mixed choir and chamber orchestra (1978)

- Werner Wehrli : Five songs op.23

- Justus Hermann Wetzel : Fifteen poems op.11

- Matthias Bonitz : Levels (2016)

literature

reference books

- Ursula Apel (Ed.): Hermann Hesse: People and key figures in his life. An alphabetical annotated list of names with all sources in his works and letters. 3 volumes. Saur, Munich 1989/93, ISBN 3-598-10841-9 .

- Gunnar Decker : The magic of the beginning. The little Hesse lexicon. Structure, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-7466-2346-7 .

To life and work

- Fritz Böttger: Hermann Hesse. Life, work, time . Verlag der Nation, Berlin 1990. ISBN 3-373-00349-0

- Albert M. Debrunner: Hermann Hesse in Basel. Literary walks through Basel. Orell Füssli Verlag 2011, ISBN 978-3-7193-1571-9

- Gunnar Decker: Hermann Hesse. The wanderer and his shadow. Biography. Carl Hanser, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-446-23879-4 .

- Eva Eberwein, Ferdinand Graf von Luckner (photographs): Hermann Hesse's garden. About the rediscovery of a lost world. DVA, Stuttgart 2016, ISBN 978-3-421-04034-3 .

- Helga Esselborn-Krumbiegel: Hermann Hesse. Series: Literature Knowledge for School and Study, Reclam Universal Library No. 15208, Stuttgart 1996, ISBN 3-15-015208-9 .

- Thomas Feitknecht: Hermann Hesse. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland . December 13, 2007 , accessed January 27, 2020 .

- Ralph Freedman: Hermann Hesse - author of the crisis. A biography. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1982 and 1991, ISBN 3-518-38327-2 .

- Detlef Haberland , Géza Horváth (ed.): Hermann Hesse and the modern age. Discourses between aesthetics, ethics and politics . Praesens, Vienna 2013, ISBN 978-3-7069-0760-6 .

- Reso Karalaschwili: Hermann Hesse - character and worldview. Studies. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1993, ISBN 3-518-38656-5 .

- Thomas Lang : Always home . Novel [about Hesse's marriage to Mia Bernoulli]. Berlin Verlag, Munich / Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-8270-1333-0 .

- Michael Limberg: Hermann Hesse. Life, work, effect. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2005, ISBN 3-518-18201-3 .

- Volker Michels (Ed.): About Hermann Hesse. 2 volumes. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1976/77, ISBN 3-518-06831-8 and ISBN 3-518-06832-6 .

- Eike Middell : Hermann Hesse. The imagery of his life. Reclam, Leipzig 1972; 5. A. ibid. 1990, ISBN 3-379-00603-3 .

- Joseph Mileck: Hermann Hesse - poet, seeker, confessor. A biography. Bertelsmann, Munich 1979; Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1987, ISBN 3-518-37857-0 .

- Helmut Oberst: Get to know Hermann Hesse. Life and work. Schulwerkstatt-Verlag, Karlsruhe 2019, ISBN 978-3-940257-26-0 .

- Martin Pfeifer: Hermann Hesse. In: Hartmut Steinecke (ed.): German poets of the 20th century. Erich Schmidt Verlag, 1994, ISBN 3-503-03073-5 , p. 175 ff. (Books.google.de)

- Alois Prinz : "And every beginning has a magic inherent in it". The life story of Hermann Hesse. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2006, ISBN 3-518-45742-X .

- Bärbel Reetz: Hesse's women . Insel, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-458-35824-4 .

- Ernst Rose: Hesse, Hermann. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 9, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1972, ISBN 3-428-00190-7 , pp. 17-20 ( digitized version ).

- Hans-Jürgen Schmelzer: On the trail of the steppenwolf. Hermann Hesse's origin, life and work. Hohenheim, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-89850-070-5 .

- Christian Immo Schneider: Hermann Hesse. Beck, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-406-33167-X .

- Herbert Schnierle-Lutz: In the footsteps of Hermann Hesse. Calw, Maulbronn, Tübingen, Basel, Gaienhofen, Bern and Montagnola. Insel, Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-458-36154-1 .

- Heimo Schwilk : Hermann Hesse. The life of the glass bead player . Piper, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-492-05302-0 .

- Sikander Singh : Hermann Hesse. Reclam, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-15-017661-1 .

- Siegfried Unseld : Hermann Hesse. Work and impact history. Insel, Frankfurt am Main 1987, ISBN 3-458-32812-2 .

- Klaus Walther : Hermann Hesse. DTV, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-423-31062-6 .

- Volker Wehdeking: Hermann Hesse. Tectum Verlag, Marburg 2014, ISBN 978-3-8288-3119-3 .

- Carlo Zanda: Hermann Hesse, his world in Ticino. Friends, contemporaries and companions. Original title: Un bel posticino ; Translated from Italian by Gabriela Zehnder. - Limmat Verlag, Zurich 2014.

- Bernhard Zeller : Hermann Hesse. New edition. Rowohlt Taschenbuch, Reinbek 2005, ISBN 3-499-50676-9 .

Documentary film

-

Hermann Hesse - His first paradise. Documentary film by Hardy Seer. Seerose Filmproduktion, Füssen 2012, ISBN 978-3-929371-24-6 .

A documentation about Hesse's first own house in Gaienhofen on Lake Constance and his time from 1904 to 1912. Participants and interviewees: Simon Hesse (grandson of the writer), Alois Prinz (writer and Hesse biographer), Eva Eberwein (biologist and owner of the Hermann-Hesse-Haus), Ruediger Dahlke (psychotherapist, doctor and author), Ute Hübner (director of the Hermann-Hesse-Höri-Museum Gaienhofen), Volker Michels (director of the Hesse edition archive). - Hermann Hesse - The way inside. Documentation by Andreas Christoph Schmidt . Schmidt and Paetzel, Berlin 2012. Film portrait on the 50th anniversary of death. Interview partners in this film are Volker Michels (editor of the Hesse Editionsarchiv), writer Adolf Muschg , Silver Hesse (grandson of Hermann Hesse), Heimo Schwilk (Hesse biographer) and the American literature professor Theodore Ziolkowski .

- Hermann Hesse Superstar - Documentation. Documentary film, Andreas Ammer, ARD, May 3, 2012

Web links

- Literature by and about Hermann Hesse in the catalog of the German National Library

- Publications by and about Hermann Hesse in the Helveticat catalog of the Swiss National Library

- Works by and about Hermann Hesse in the German Digital Library

- Works by Hermann Hesse in Suhrkamp and Insel Verlag

- Rebekka von Mallinckrodt : Hermann Hesse. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- Works by Hermann Hesse in Project Gutenberg ( currently usually not available for users from Germany )

- Works by Hermann Hesse in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Hermann Hesse's estate in the HelveticArchives archive database of the Swiss National Library

- Hermann Hesse in the literature archive of the Austrian National Library

- Thomas Feitknecht: Hesse, Hermann. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- Link collection ( memento from April 27, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) of the University Library of the Free University of Berlin

- International Hermann Hesse Society V.

- Hermann Hesse House (1907–1912) in Gaienhofen

- literaturkritik.de 8/2012 on the 50th anniversary of death: 13 articles

- Regina Bucher: Hermann, Hesse. In: Sikart

- Hermann-Hesse-Page (HHP), University of California, Santa Barbara, Prof. Gunther Gottschalk (English and German)

- Hermann Hesse Collection in the archive of the Academy of Arts, Berlin

- Hermann Hesse research

- Fondazione Hermann Hesse Montagnola The Hermann Hesse Museum in Montagnola was established in 1997 in the rooms of the Torre Camuzzi

- Hermann Hesse In: ticinARTE

- Hermann Hesse. In: Stroux.org

Remarks

- ↑ The dating follows recent studies by Roland Stark, cf. Image and image. Hermann Hesse in friendship with Fritz and Gret Widmann , Hermann-Hesse-Höri-Museum, Gaienhofen 2008, ISBN 978-3-9808992-3-9 . In older literature, April 1926 is given as the time the photo was taken, for example in Friedrich Pfäfflin u. a .: Hermann Hesse 1877–1977. Stations in his life, his work and its impact . Catalog of the commemorative exhibition for Hesse's 100th birthday in 1977, Marbach a. N. 1977, p. 97.

- ^ Literature archive: Hermann Hesse Archive. Academy of the Arts, accessed November 19, 2012 .

- ↑ a b c Hermann Hesse: Biography . City of Calw, 2011.

- ^ Rebekka von Mallinckrodt : Hermann Hesse. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- ^ Hugo Ball : Hermann Hesse. His life and his work. S. Fischer, Berlin 1927 ( Freilesen.de ).

- ↑ a b c Citizens of the world - Hermann Hesse's supranational and multicultural thinking and working. Exhibition by the Hermann Hesse Museum in Calw from July 2, 2009 to February 7, 2010.

- ^ Siegfried Greiner: Hermann Hesse - Youth in Calw . 1981, p. 124/125: Fig. 11 (photo of the same house around 1930) with accompanying explanatory text.

- ^ Marie Hesse: Marie Hesse Biography ( Memento from November 23, 2015 in the Internet Archive ). City of Calw, 2015.

- ↑ Martin Pfeifer: Explanations of Hermann Hesse's novel Das Glasperlenspiel. C. Bange, Hollfeld / Ofr. 1977 (= King's Explanations and Materials. Volume 316 / 17a). ISBN 3-8044-0191-0 , p. 6.

- ↑ Volker Michels (Ed.): About Hermann Hesse . Volume 1: 1904–1962, representative text collection during Hesse's lifetime . Frankfurt am Main 1979, ISBN 3-518-06831-8 , p. 400.

- ^ A b Hermann Hesse: Letters . Verlag Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1964, p. 414.

- ↑ The toponym Gerbersau invented by Hesse is a pseudonym for Calw. It is based on the name of the nearby town of Hirsau and describes Calw as "Gerber- Au ".

- ^ Siegfried Greiner: Hermann Hesse - Youth in Calw. 1981, p. VIII.

- ↑ The sculpture can be seen in the photo of the Nikolausbrücke above the right bridge arch as the first figure to the left of the center of the arch.

- ↑ Timeline. In: Hermann Hesse: Gertrud. Novel. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1983 (= Suhrkamp Taschenbuch. Volume 890), ISBN 3-518-37390-0 , pp. 194–203, here: p. 194.

- ^ Heimo Schwilk: Hermann Hesse. 2012, p. 43.

- ^ Hesse: Childhood and youth before nineteen hundred. Volume 1, p. 268 f.

- ^ Hermann Hesse: Romantic songs at Projekt Gutenberg-DE , accessed on April 1, 2020

- ↑ See the chapter “Return to Orplid. A landscape of memories in Tübingen, almost intact ”about Hesse's time in Tübingen in Albert von Schirnding: Literarian Landscapes Island, Frankfurt 1998. Another chapter deals with the“ Presselsche Gartenhaus ”, to which Hesse dedicated a novel of the same name, with Wilhelm Waiblinger , Hölderlin and Eduard Mörike as protagonists .

- ^ Dominik Heitz: Authors in Riehen: The writer Hermann Hesse. Retrieved August 22, 2019 .

- ↑ Basler Buildings, Hintere Württemberger Hof: Poem by Hesse, Hintere Württemberger Hof. Retrieved October 12, 2019 .

- ↑ Short biography on die-biografien.de

- ^ Marc Krebs: Maria Bernoulli. Retrieved August 23, 2019 .

- ↑ Volker Michels (Ed.): Hermann Hesse: Music. Reflections, poems, reviews and letters. With an essay by Hermann Kasack . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1976 (expanded edition. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1986, ISBN 3-518-37717-5 , p. 179).

- ^ Eduard Zimmermann: 1906, bust of Hermann Hesse. Retrieved November 1, 2019 .

- ↑ Barbara Hess: Hermann Hesse and his publishers: the author's relationships with the publishers E. Diederichs, S. Fischer, A. Langen and Suhrkamp . Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, 2000, ISBN 3-447-04267-2 ( google.at [accessed on November 15, 2018]).

- ^ Hermann Hesse: All works in 20 volumes and 1 register volume (ed.): Volker Michels, Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2003, ISBN 3-518-41114-4 , volume 21, p. 19 (time table).

- ↑ Martin Radermacher: Hermann Hesse - Monte Verità: The search for truth beyond the mainstream at the beginning of the 20th century. ( Memento of March 7, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) In: Journal for Young Religious Studies. 2011.

- ^ Ernst Morgenthaler: Portrait. Retrieved October 21, 2019 .

- ^ Wilhelm Schäfer: Dedication on page 7. Karl Stauffer's life story - a chronicle of passion. Retrieved June 12, 2019 .

- ↑ Volker Michels (Ed.): Hermann Hesse: Music. Reflections, poems, reviews and letters. 1986, p. 179.

- ↑ Gunter E. Grimm, Ursula Breymayer, Walter Erhart: "A feeling of freer life". German poets in Italy. Metzler, Stuttgart 1990, ISBN 3-476-00710-3 , p. 219.

- ^ Hermann Hesse and Albert Welti

- ↑ Volker Michels (Ed.): Hermann Hesse: Music. Reflections, poems, reviews and letters. 1986, p. 179.

- ^ Heimo Schwilk: Hermann Hesse. 2012, p. 181. For more on Hesse's initially ambiguous attitude towards war, see Heimo Schwilk: Hermann Hesse. 2012, pp. 179–189, and Gunnar Decker: Hermann Hesse. 2012, pp. 289-297.

- ^ Georg A. Weth: Hermann Hesse in Switzerland. 2004, ISBN 3-7844-2951-3 , p. 24.

- ^ Letter to Hans Sturzenegger dated January 3, 1917.

- ↑ Thomas Mann: Hermann Hesse on his seventieth birthday . In: Collected works in thirteen volumes . Second, revised edition (first 1960). tape X . S. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt a. M. 1974, ISBN 3-10-048177-1 , pp. 519 .

- ↑ Volker Michels (Ed.): Hermann Hesse: Music. Reflections, poems, reviews and letters. 1986, p. 173.

- ↑ Andreas Dorschel , Saint Hermann. The correspondence between the poet Hesse and the Ball couple. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung . No. 292, December 19, 2003, p. 16.

- ↑ Materials on Hesse's Siddhartha , Volume 2, p. 302, cit. January 24, 1973.

- ^ Hermann Hesse: Walk in Würzburg. Tschudy & Co, St. Gallen o. J. (private printing with the permission of the poet at the instigation of Franz Xaver Münzel in Baden for the benefit of the city of Würzburg).

- ↑ Petra Trinkmann: Madonnas and fish. Hermann Hesse. In: Kurt Illing (Ed.): In the footsteps of the poets in Würzburg. Self-published (printing: Max Schimmel Verlag), Würzburg 1992, pp. 81–89; here: p. 82.

- ↑ Volker Michels (Ed.): Hermann Hesse: Music. Reflections, poems, reviews and letters. With an essay by Hermann Kasack ( Hermann Hesse's relationship to music ). Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1976. (extended edition. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1986, ISBN 3-518-37717-5 , p. 211 f)

- ↑ Cf. Hesse's statements about Schoeck's compositions in: Chris Walton, Martin Germann (eds.): Hermann Hesse and Othmar Schoeck, der Briefwechsel. (= Schwyzer Hefte. Volume 105). Culture Commission Canton Schwyz, Schwyz 2016, ISBN 978-3-909102-67-9 , esp. Pp. 102 and 112-113.

- ↑ Volker Michels (Ed.): Hermann Hesse: Music. Reflections, poems, reviews and letters. 1986.

- ^ Hermann Kasack: Hermann Hesse's relationship to music. In: Volker Michels (Ed.): Hermann Hesse: Music. Reflections, poems, reviews and letters. With an essay by Hermann Kasack. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1976. (extended edition. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1986, ISBN 3-518-37717-5 , pp. 7-20)

- ^ Hermann Hesse: All works in 20 volumes and 1 register volume. Edited by Volker Michels. Volume 14, Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2003, ISBN 3-518-41114-4 , p. 151.

- ↑ Barbara Hess: Hermann Hesse and his publishers. The author's relationships with the publishers E. Diederichs, S. Fischer, A. Langen and Suhrkamp. Harrassowitz, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-447-04267-2 , p. 73.

- ↑ Information from the Nobel Foundation on the award ceremony in 1946 to Hermann Hesse (English) with autobiography (English)

- ↑ Carina Gröner illuminates the economic relation of this part of the extensive correspondence in: Carina Gröner: Yes, taking and giving…. Pen friendship between life's work and business model. The Hesse collections in the Vadiana canton library in St. Gallen. St. Gallen 2012.

- ^ Heimo Schwilk: Hermann Hesse. 2012, p. 335.

- ↑ Hans Jakob Meyer: 1962, tomb for Hermann Hesse. In: Website HJ Meyers. Retrieved August 8, 2019 .

- ↑ Harley Ustus Taylor: Homoerotic elements in the novels of Hermann Hesse. In: West Virginia Philological Papers. Vol. 16, Morgan, West Virginia, pp. 63-71.

- ^ Eleonore Vondenhoff: Visit to Hermann Hesse. In: Volker Michels (ed.): Hermann Hesse in eyewitness reports. 1991, p. 345. The sculpture is based on a photo that the youngest son Martin Hesse took in October 1954 of his father, standing together with his eldest son Bruno Hesse, in front of the studio veranda of the Casa Rossa in Montagnola (cf. Hermann Hesse: On the value of old age. 2007, p. 12). The very upright posture, even at an advanced age, is confirmed, for example, by the 78-year-old author being included in his library (ibid., P. 70).

- ↑ Tom Wolfe: The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test . Heyne, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-641-02480-2 , pp. 200-201 .

- ↑ Carlos Santana, Ashley Kahn, Hal Miller: The Sound of the World. My life . Riva, Munich 2015, ISBN 978-3-86883-561-8 , pp. 245 .

- ↑ Press release of January 2, 2006 on the yearbook of the International Hermann Hesse Society

- ↑ Calw. The Hermann-Hesse-Stadt calw.de

- ↑ a b Hermann-Hesse-Museum calw.de

- ↑ Timetable www.hermann-hesse-bahn.de, accessed on July 4, 2020

- ↑ Over 100 poems were set to music. See Volker Michels (ed.): Hermann Hesse: Music. Reflections, poems, reviews and letters. 1986, pp. 236-241.

- ^ International Hermann Hesse Society: Adolf Muschg first laureate of the newly awarded prize of the International Hermann Hesse Society

- ↑ Affinity: Udo L. and Hermann H. - two brothers in spirit. ( Memento of the original from April 19, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. udo-lindenberg-stiftung.de

- ↑ Product information on the paperback Mein Hermann Hesse: Ein Lesebuch. udo-lindenberg.de

- ↑ Homepage of the Udo Lindenberg Foundation ( Memento of the original from January 7, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Information about the holdings of the DLA about Hermann Hesse. ( Page no longer available , search in web archives )

- ↑ Volker Michels (Ed.) Hermann Hesse: Music. Reflections, poems, reviews and letters. 1986, p. 173.

- ↑ Joseph Mileck: Hermann Hesse: Life and Art . University of California Press, Berkeley 1981, pp. 356 (English). - Joseph Mileck: Hermann Hesse: poet, seeker, confessor (= Suhrkamp-Taschenbuch . No. 1357 ). Suhrkamp Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt 1987, ISBN 3-518-37857-0 , pp. 395 . - Rudolf Koester: Hermann Hesse (= Metzler Collection . Volume 136 ). JB Metzlersche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Stuttgart 1975, p. 27 .

- ^ Peace Prize of the German Book Trade 1955: Hermann Hesse Documentation with laudation and acceptance speech (PDF)

- ↑ Hermann Hesse Bahn.

- ^ Hesse Museum Gaienhofen

- ↑ Mia and Hermann Hesse House

- ↑ Website Museo Hermann Hesse in Montagnola

- ↑ museum.de

- ↑ hermann-hesse.de/museen/tuebingen

- ^ Hermann Hesse: Romantic songs at Projekt Gutenberg-DE , accessed on April 1, 2020

- ↑ Frequent reprints. The volumes are arranged chronologically. The individual titles are listed online on the publisher's website.

- ↑ Volker Michels (Ed.): Hermann Hesse: Music. Reflections, poems, reviews and letters. 1986, p. 173.

- ↑ bonitz-classic.de: levels

- ↑ badische-zeitung.de , April 15, 2017, Andreas Kohm: Children, Wives and Cats (April 15, 2017)

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Hesse, Hermann |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Hesse, Hermann Karl (full name); Sinclair, Emil (pseudonym) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German-Swiss writer, poet and painter |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 2, 1877 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Calw , Kingdom of Württemberg , German Empire |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 9, 1962 |

| Place of death | Montagnola , Canton Ticino , Switzerland |