Étienne Lenoir (inventor)

Jean-Joseph Étienne Lenoir (born January 12, 1822 in Mussy-la-Ville ( Grand Duchy of Luxembourg , since 1839 Belgium ); † August 4, 1900 in La Varenne-Saint-Hilaire, part of Saint-Maur-des-Fossés ( France )) was an inventor with 80 patents and a businessman. He was a pioneer in the construction of heat engines and developed the first functional gas engine , which he also installed in a car and boats. Lenoir was a Knight of the Legion of Honor and received French citizenship.

youth

Lenoir was born as the third of eight children in the 800-strong community of Mussy-la-Ville near Virton . He seems to have opted for a technical career early on, but his family could not afford such training. He left his homeland in 1838 apparently without regrets. It is said that he threw away his shoes at the exit of the village because he did not want to take a crumb of earth with him from a country that did not understand what he wanted. He walked via Reims and Meaux to Paris , where he arrived in the summer of 1838. He earned his living during this time by doing odd jobs on farms.

Inventions before the gas engine

He found a job as a waiter in the Auberge de l'Aigle d'Or on rue du Temple in the 3rd arrondissement , where he also lived. In his spare time he read and experimented in the inn's basement. An enameller in the neighborhood hired him as a worker. Lenoir now dealt with the problem of producing white enamel by means of oxidation . He found a formula and received his first patent on it in 1847. The process was mainly used for the manufacture of dials .

Lenoir was also interested in electrolysis and developed a special process for silver-plating or copper-plating small round objects. The goldsmith Charles Christofle bought it from him and recommended that he have it patented. That happened in 1851. Christofle applied the process to the ornamental design of the Paris Opera .

Lenoir did not have any success with the development of an electromagnetic motor, but between 1855 and 1857 several patents for completely different technical solutions followed: in the railway sector he worked on electrical signals and safety systems such as brakes, he developed a regulator for dynamos, invented a mechanical kneading machine, one Water meter and a method for coating glass surfaces. Lenoir was now able to make a living from selling his inventions. At that time he lived on Boulevard du Prince-Eugène 139 - renamed Boulevard Voltaire in 1870.

Ever since he read about the Fardier by Nicholas Cugnot and saw the vehicle at the École Centrale des Arts et Manufactures (where it still stands today), he wondered how such a construction could be better implemented. The Fardier was over seven meters long, weighed four tons and had a state-of-the-art, inefficient steam engine as its drive. The brake was also inadequate and the steering mechanism cumbersome because the machine's piston was acting on the machine's steered front wheel. Added to this was the weight of the boiler mounted directly above . During his numerous visits to the École Centrale , Lenoir met the railway engineer Alphonse Beau de Rochas . Known as difficult, Rochas helped Lenoir with his research.

The gas engine

Lenoir was convinced that the potential of the steam engine was largely exhausted. In addition, the disadvantages were obvious: the machine has to be heated up for a long time before work can be carried out, and it is heavy. Lenoir used the new financial independence to build his own engine. He attended free lectures at the École Centrale and after a few months he began implementing them in the mechanical workshop of his friend Hippolyte Auguste Marinoni (1823-1904) on Rue de la Roquette in the 11th arrondissement . Marinoni, son of a police officer and inventor of a machine for processing rice and cotton , made a fortune with his rotary printing press .

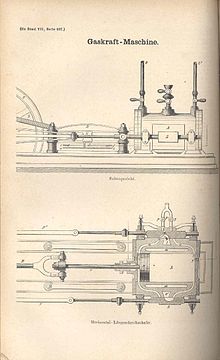

functionality

The breakthrough came in 1858 with a stationary engine . Lenoir developed the single cylinder further into the first usable gas engine in the course of 1859 . One of its advantages was that it could be supplied with energy directly in the house: the engine only had to be connected to the municipal gas supply. It also ran very quietly; however, consumption was high.

The construction is a combination of already known elements with their own ingenuity and has some similarities with the steam engine. Instead of burning the fuel outside, as in the steam engine, and then directing the heat into the cylinder, in the gas engine it is generated by combustion inside. In the Lenoir engine, in contrast to the flying piston engine by Nikolaus Otto and Eugen Langen, the drive acts directly on the crankshaft . Lenoir's engine works as a two-stroke without compression; a brochure from the Musée des Arts et Métiers describes it as a "one-stroke cycle with two half-cycles", with the inlet and combustion forming the first half-cycle and the exhaust forming the second half-cycle.

An ignition mixture of coal gas and air drives the piston based on a patent by Robert Street, which in turn drives the flywheel . It is fed alternately to each side of the piston with a flat slide so that it works in both directions (double-acting), analogous to the gas engine by Philippe Lebon (1767–1804). The movement of the piston simultaneously expels the gas burned in the previous cycle on the other side. The slide is driven by the crankshaft via an eccentric .

The ignition system invented by Lenoir, which he called inflammateur , consists of two of the galvanic elements developed by Robert Wilhelm Bunsen , which transmit low voltage to a Rühmkorff induction apparatus ( induction coil ). The spark plug developed by Lenoir is based on a principle discovered by Isaac de Rivaz (1752–1828). It consists of a copper jacket bolt that contains a porcelain pin with the ignition wire. Lenoir also designed the distributor himself.

As is usual with steam engines, Lenoir used a centrifugal governor with balls to achieve a smooth run. The prototype turned at 130 rpm, the production version at around 100 rpm. Such an engine weighed about 100 kg and had a displacement of about 2.5 liters. Lenoir calculated a consumption of 500 liters of gas per horsepower and hour, in fact it is over 3000 liters per horsepower and hour. Lenoir's innovations include the valve in the cylinder head, the rocker arm and the ignition system.

In November 1859, Lenoir applied for a patent for the motor. About 20 people were invited to the solemn signing of the document on January 23, 1860 with a demonstration. The patent, issued for a period of 15 years, covers an “ Air Expansion Engine by Combustion of Gas”, dated January 24, 1860 , and bears the number 43624.

weaknesses

The Lenoir engine had some fundamental disadvantages: For physical reasons, the maximum efficiency of atmospheric engines is generally low; concrete figures speak of 3 to 5 percent. A modern car with a gasoline engine achieves 30 percent. As a result, the engine also used a lot of fuel. Since the piston was exposed to explosions on both sides, very high operating temperatures developed. With the materials of the time and the possible manufacturing precision, there was quickly a risk of a piston jamming . Accordingly, the engine required a lot of lubricating oil and a very powerful water cooling system .

production

Some engines were initially made by Marinoni. As early as 1859, Lenoir was looking for investors. The Société des Moteurs Lenoir was founded with the investor Gautier, with its headquarters at 101 Boulevard de Sebastopol. The company was capitalized with two million francs . Like Marinoni's factory, the production facility was on Rue de la Roquette; it is unclear whether it was housed in the same building.

The first series machine with an output of 4 hp using the calculation method at the time was delivered to the master lathe operator Levêque at 35 rue Rousselet in the 7th arrondissement in May 1860 . In the following months, 380 engines with 1 to 4 HP left the factory .; By 1864, 130 Lenoir engines were running in Paris alone. The engine was received very benevolently. He received an award at the World Exhibition in London in 1862 .

A standard engine cost between 1100 and 2800 francs. It was available with ½, 1, 2 or 3 HP and on special order as a two-cylinder with 4 HP.

Advantages such as the simple installation, the immediate operational readiness without preheating, the reliability and the smoothness contrasted with disadvantages; In the beginning there were no engines with more than 4 HP and the purchase price and maintenance costs were high. They were often used in handicrafts and small family businesses such as clothing manufacturers, in mechanical workshops or in printing shops .

Lenoir engines were manufactured under license in Germany, Great Britain and the USA.

Boats

In 1861 Lenoir put a 2 hp engine in a boat on a trial basis. Since gas could not yet be carried, he had to find another fuel supply. Instead of coal gas, he used petroleum . This in turn made a device for mixture preparation, i.e. an early form of the carburetor , necessary.

In 1865 Lenoir built a 6 hp engine into a twelve meter long boat for the publisher of Le Monde Illustré magazine , Dalloz. The owner used it for pleasure trips on the Seine .

Hippomobile

In 1863 he installed a version of the engine with 1½ HP, which also worked independently of the stationary gas supply, in a three-wheeled car called the Hippomobile . Here he used a turpentine- based fuel . The body consisted of a high-lying cuboid structure. Underneath there was a wooden compartment with the drive technology.

With this vehicle he drove the 18 km long distance from his workshop to Joinville-le-Pont and back in about three hours. This resulted in an average of 6 km / h including breaks. The information about the journey comes from Lenoir himself, but is considered certain. Files held by the Automobile Club de France document the journey and a patent from 1864. The vehicle was not a success because of its heavy weight and the engine turning at only 100 rpm.

A second automobile was built in 1865 and was sold to the Russian Tsar Alexander II . None of the vehicles have survived; the hippomobile was destroyed in the Franco-Prussian War 1870–1871 .

Airship

The German mechanical engineer Paul Haenlein had been working on a semi-rigid airship since at least 1864 , which he wanted to propel with a gas engine and thereby make it steerable. The gas for this should be taken from the hull of the airship by means of a distributor pipe; to the same extent that gas was consumed, this should be compensated for by pumping up the balloonet with compressed air . He received a patent for this on April 1, 1865. The first trip was supposed to take place in Wiener Neustadt , but was moved to Brno at short notice . It was successful in that the airship actually rose to 20 meters and reached a speed of 18 km / h. The aircraft, which was always secured by soldiers, remained below its capabilities because the Brno town gas was eleven percent heavier than the one from Wiener Neustadt, for which the airship was designed. This made Aeolus 250 kg heavier than intended.

Later life and further inventions

The success of Lenoir's gas engines only lasted about five years. At the World Exhibition in Paris in 1867 , Otto and Langen's innovative aviation piston engine competed with 14 gas engines from different manufacturers and prevailed. Lenoir also acknowledged its superiority and even called his own invention "monstrously imperfect". Most Lenoir engines were retired after a few years.

Étienne Lenoir had already sold the rights to his gas engine to the Compagnie Parisienne du Gaz in 1863 and worked alongside and after the gas engine on numerous other different inventions. For example, he constructed an apparatus "for the telegraphic transmission of written or drawn documents", which was even used for military purposes on the occasion of the siege of Paris (1870–1871) . Further work concerned a chemical method of tanning leather with ozone . The process massively shortened the tanning process, and it was also more health-friendly for the employees.

Lenoir spent his retirement in peaceful affluence in his apartment on Rue du Bac N ° 114 in the La Varenne-St. Hilaire in the 7th arrondissement of Paris . From here he often went fly fishing to the nearby Seine , but remained active and followed the further development of the internal combustion engine with interest. He recognized the superiority of Otto's four-stroke engine and even worked on a four-stroke version of the gas engine himself, which he patented in 1883. This was produced from 1894 by Mignon & Rouart and the Compagnie Parisienne du Gaz . Lenoir improved the efficiency to 15 percent. In 1886 another boat was built that was powered by such an engine.

Jean-Joseph Étienne Lenoir passed away quietly on August 4, 1900. He was buried in the Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris .

Appreciation

Jean-Joseph Étienne Lenoir did not invent either the explosion engine or the gas engine. Nevertheless, this is undoubtedly the most important of his 75 patented inventions. It is Lenoir's merit to have arranged individual components of known constructions in a sensible way and to have expanded them with his own ideas with great creative élan. His invention was undoubtedly the first really operational gas engine; As such, it was manufactured industrially and for a time, for a limited type of use, was a real alternative to the steam engine and laid one of the foundations for mass-produced motor vehicles on land, on water and in the air.

Gottlieb Daimler saw the engine in Paris as early as 1860 without being impressed. Lenoir's invention has a different, rather unexpected effect: In 1861, Nicolaus Otto had a Lenoir engine built and realized that it would run better with alcohol. The development of a reliable carburetor for mixture preparation took a long time; one of the reasons that Otto only received his patent in 1878. It is not without irony that Lenoir was on the right track here too; his petroleum or turpentine powered vehicles also needed a carburetor.

In 1864 Otto presented his aviation piston engine . This was also uncompacted. It was a further logical step away from steam engine construction. The explosion only occurred on one side of the piston; the drive shaft now regulated the speed of the piston movement independently of the speed of the flywheel, which led to a drastic reduction in fuel consumption.

Was the Hippomobile the first "real" car? In the sense that it could cover a greater distance on its own, and far better than the Fardier and other earlier designs could: Yes. The Automobile Club de France (ACF) apparently also saw it that way, when it presented Lenoir with a plaque on July 16, 1900 "in recognition of the great merits of the invention of the gas engine and the construction of the world's first automobile". However, the gas engine was poorly suited for mobile applications. It is no coincidence that Lenoir only fitted three boats and two land vehicles with his engine.

After him, Nicolaus Otto based the development of his four-stroke engine on this gas engine, which alone became an important milestone on the way to the automobile. For the experimental physicist Louis Leprince-Ringuet (1901–2000) Lenoir was "one of the 100 greatest inventors of all time".

Original Lenoir engines are exhibited in the Deutsches Museum in Munich , Cologne , Vienna , Prague and London; the aforementioned Musée des Art et Métiers in Paris owns two (from 1861 and 1862) as well as a model of a Lenoir four-stroke engine and a Lenoir telegraph. Cugnots Fardier is also presented here.

Honors

- 1878: Prix Montyon of the Institut de France for his method of surface treatment of glass

- 1880: Grand prix d'Argenteuil of the Société d'encouragement à l'Industrie nationale for its method of tanning leather

- 1881: French citizenship

- 1881: Chevalier (knight) of the French Legion of Honor for his services in the defense of Paris (telecommunications); along with citizenship

- 1900: Merit plaque of the ACF

- Monaco special postage stamp € 1.75 150 years of the invention of the gas engine

- Special stamp Belgium € 4 + 1

A marble statue in Virton and a monument in Arlon were erected in Lenoir's honor . There is also a street named after him here. A marble inscription can be found in the Musée des Arts et Métiers , there are further inscriptions on the birthplace on Grand rue and on the primary school in Mussy-La-Ville.

literature

- Richard v. Frankenberg, Marco Matteucci: History of the Automobile (1973), Sigloch Service Edition, Künzelsau / STIG Torino; without ISBN

- B. von Lengerke: Automobile races and competitions (1894–1907), Fachbuchverlag-Dresden, 2014, facsimile of a work from 1908 (Richard Carl Schmidt & Co., Berlin); ISBN 3-95692-272-7 , ISBN 978-3-95692-272-5 , paperback

Web links

- Revue de la Société d'Entraide des Membres de la Légion d'Honneur, No. 107, May 1990, pp. 16–18: Biography of Jean-Joseph Étienne Lenoir (1822–1900) (French, PDF, 88 KiB)

- LE MOTEUR LENOIR ( Memento of November 27, 2003 in the Internet Archive ) (Brochure about the lenoir gas engine; French, PDF; 360 kB)

- Engine Maturity, Efficiency, and Potential Improvements, pp. 7–8 (English; PDF file; 2.63 MB)

- machine-history.com: Hippomobile ( Memento from May 2, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) (accessed on August 14, 2013)

Remarks

- ^ Frankenberg / Matteucci call the engine a three-stroke (intake - combustion - exhaust); there is no compression cycle (p. 15).

- ↑ According to Frankenberg / Matteucci, two pistons run in the cylinder (p. 15).

- ↑ «un moteur à air dilaté par la combustion des gaz»

- ^ Another peculiarity about Frankenberg / Matteucci: They mention (probably erroneously) June 24th, 1860; no other source confirms this date (p. 15).

- ↑ According to Wertpapiergeschichte.com 330 copies within five years

- ↑ "en reconnaissance de ses grands mérites en tant qu'inventeur du moteur à gaz et constructeur de la première automobile du monde"

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae Revue de la Société d'Entraide des Membres de la Légion d'Honneur, No. 107

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Jean-Joseph Étienne Lenoir and the “Société des Moteurs Lenoir” ( Memento from July 27, 2013 in Internet Archive ) on Wertpapiergeschichte.com, accessed on July 21, 2013

- ↑ a b c d e Musée des Arts et Métiers: Carnet Lenoir

- ↑ Max Ensslin: Today's gas and petroleum engines and their importance for industry. In: Polytechnisches Journal , 1900, Volume 315 (pp. 234-239). Online , accessed January 29, 2020.

- ↑ a b Lengerke: Automobile Races and Competitions (1894–1907), facsimile of a work from 1908, p. 8.

- ↑ Paul Haenlein and his airship “Aeoius” on austroclassic.at, accessed on July 21, 2013

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Lenoir, Etienne |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Lenoir, Jean Joseph Étienne (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French inventor and businessman |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 12, 1822 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Mussy-la-Ville , Luxembourg , now Belgium |

| DATE OF DEATH | 4th August 1900 |

| Place of death | La Varenne-Saint-Hilaire , France |