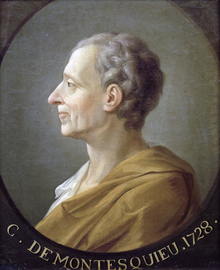

Charles de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu

Charles-Louis de Secondat, Baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (baptized January 18, 1689 at La Brède Castle near Bordeaux ; † February 10, 1755 in Paris ), known under the name of Montesquieu , was a French writer , philosopher and political theorist the enlightenment . He is considered a forerunner of sociology , an important political philosopher and co-founder of modern history .

Although the moderate pioneer of the Enlightenment was also a successful fiction writer for his contemporaries , he went down in intellectual history primarily as a historico-philosophical and state-theoretical thinker and still influences current debates today .

Life and work

Beginnings and early literary success

Montesquieu was born as the son of Jacques de Secondat (1654–1713) and Marie-Françoise de Pesnel (1665–1696) in a family belonging to the high official nobility , the so-called "noblesse parlementaire". The exact date of his birth is not known, only that of his baptism, January 18, 1689. He was probably born only a few days earlier.

As the eldest son, he spent his childhood on the La Brède estate, which his mother had brought into the marriage. His father was a younger son from the noble family of the de Secondat, who had become Protestant, but returned to Catholicism in the wake of Henry IV and were rewarded with the elevation of their family seat Montesquieu to a barony. With the dowry he had married, his grandfather had bought the office of president of the court (président à mortier) at the Parlement of Bordeaux , the highest court in Aquitaine .

At the age of seven, Montesquieu lost his mother. From 1700 to 1705 he attended the college of the Oratorian monks in Juilly, not far from Paris, as a boarding school student , which was known for the critical spirit that reigned there and where he met several cousins from his extensive family. He acquired in-depth knowledge of Latin, mathematics and history and wrote a historical drama, a fragment of which has survived.

From 1705 to 1708 he studied law in Bordeaux. After graduating and being admitted to the bar, he was given the title of baron by the head of the family, his father's childless eldest brother, and went to Paris to further his legal and other training, because he was to inherit the court presidency from his grandfather passed to the uncle. In Paris he made contact with intellectuals and began to write down all kinds of thoughts and reflections in a kind of diary.

When his father died in 1713, he returned to Château de La Brède . In 1714 he was given the office of judicial councilor (conseiller) at the Parlement of Bordeaux, surely through his uncle.

In 1715 he married, through the mediation of his uncle, Jeanne de Lartigue (~ 1692 / 93–1770), a Huguenot who paid 100,000 Frs. Brought dowry. In 1716 they had a son in quick succession; Jean-Baptiste (1716–1796) and a daughter in 1717; Marie (1717–1784) born, another daughter followed in 1727; Denise (1727-1800). The couple very often lived apart.

In addition to his work as a judge, Montesquieu continued to be interested in a wide variety of fields of knowledge. For example, after the death of Louis XIV (September 1715), he wrote an economic policy memorandum on public debt ( Mémoire sur les dettes de l'État ), addressed to Philip of Orléans , who was the regent for the underage Louis XV. ruled.

In 1716 he was accepted into the Académie von Bordeaux, one of those loosely organized circles that brought together scholars, writers and other spiritually interested people in larger cities. Here he was active with lectures and smaller writings, e.g. B. a dissertation sur la politique des Romains dans la religion ( treatise on the religious politics of the Romans ), in which he tries to prove that religions are a useful instrument for moralizing the subjects of a state.

Also 1716, d. H. shortly after the regent had strengthened the political power of the parlements (courts), which had been curtailed by Louis XIV, Montesquieu inherited his uncle's office as court president. He pursued his spiritual interests as before.

In 1721 he became famous for a letter novel that he had begun in 1717 and which was banned by the censors soon after its anonymous publication in Amsterdam: the Lettres persanes ( Persian letters ). The content of the work, which is now considered a key text of the Enlightenment , is the fictional correspondence of two fictional Persians who traveled to Europe from 1711 to 1720 and exchanged letters with people who stayed at home. In doing so, they describe - and this is the enlightenment core of the work - their correspondence partners the cultural, religious and political conditions, especially in France and especially in Paris, with a mixture of amazement, head-shaking, ridicule and disapproval (which has been popular since Pascal's Lettres provinciales at the latest The procedure was to make the reader a participant in an outside perspective and thus enable him to take a critical look at his own country). In this publication, Montesquieu deals with various topics such as religion, priesthood, slavery, polygamy, discrimination against women and the like. a. m. in the interests of clarification. In addition, a romance-like storyline about the harem ladies who stayed at home is woven into the Lettres , which was not entirely uninvolved in the success of the book.

After becoming acquainted with the Lettres , Montesquieu developed the habit of spending some time in Paris each year. Here he frequented some sophisticated salons , e.g. B. that of the Marquise de Lambert , and occasionally at court, but especially in intellectual circles.

Baron de Montesquieu was a regular visitor to the Saturday discussion group in the Club de l'Entresol , which had been founded by Pierre-Joseph Alary (1689-1770) and Charles Irénée Castel de Saint-Pierre and from 1720 (or 1724) to 1731 in the Raised ground floor apartment on Place Vendôme in Paris by Charles-Jean-François Hénault (1685–1770).

In 1725 he achieved another remarkable book success with the rococo-like, gallant pastoral little novel Le Temple de Gnide , which he supposedly found and translated in an older Greek manuscript. The now completely forgotten work was widely read until the end of the 18th century and translated into other languages several times. a. in Italian verse. It was the only one of Montesquieu's works to receive the censorship approval when it was first published.

Years of reflection and travel

The following year he sold his apparently little loved judge's office and settled in Paris, not without spending some time each year at the family castle La Brède.

In 1728 he was elected to the Académie française , albeit only at the second attempt . In the same year (soon after the birth of his youngest daughter) he went on a three-year educational and information journey through several German and Italian states, the Dutch States General and, above all, England. On February 26, 1730 he was elected a member ( Fellow ) of the Royal Society . On May 16 of the same year he became a member of the Freemason Lodge Horn’s Tavern in Westminster in London . Later, in 1735, he helped found the Paris lodge at the Hôtel de Bussy , initiated by Charles Lennox , Duke of Richmond, and John Theophilus Desaguliers .

The big fonts

In 1731 Montesquieu returned to La Brède, where he stayed for the most part from now on. In 1734 he published the book Considérations sur les causes de la grandeur des Romains et de leur décadence in Holland ( reflections on the causes of the greatness of the Romans and their decline ) . Using the example of the rise of the Roman Empire and its decline (which he sees beginning with Caesar's autocracy) , he tries to demonstrate something like a lawful course in the fate of states and at the same time to practice covert criticism of French absolutism .

His most important work was the historical, philosophical and political theory De l'esprit des lois / On the Spirit of Laws (Geneva 1748), a product of twelve years of work.

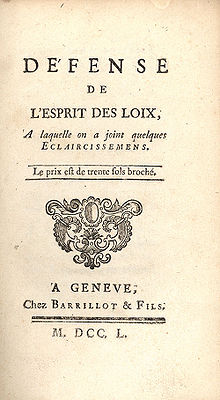

On the one hand, he names the determinants that determine the government and legal systems of individual states (e.g. size, geography, climate, economic and social structures, religion, customs and traditions); on the other hand, he formulates - not least in opposition to royal absolutism, which is unpopular in the parliamentary milieu - the theoretical foundations of a universally possible regime. The central principle for Montesquieu here, following on from John Locke , is the separation of the areas of legislation ( legislative ), jurisdiction ( judiciary ) and governance ( executive ), in other words the so-called separation of powers - a term that he does not yet use as such occurs. His book immediately attracted widespread attention and triggered violent attacks from the Jesuits , the Sorbonne and at the same time the Jansenists . In 1751 it was placed on the index of forbidden books by the Catholic Church and remained there until it was abolished in 1967. Montesquieu's defensive text, the Défense de l'Esprit des lois, published in Geneva in 1750 , had no influence on it.

He spent the last years of his life becoming increasingly blind, partly in Paris, partly on La Brède, with his youngest daughter helping him as a secretary. Among other things, he wrote an essai sur le goût dans les choses de la nature & de l'art for the Encyclopédie , but it remained a fragment. Although the editors Diderot and d'Alembert for Montesquieu originally the entries Démocratie and despotisme had provided and the product Goût already Voltaire had been promised, Montesquieu essay fragment was posthumously and reprinted in addition to Voltaire's text in the seventh volume 1757th

Montesquieu died of an infection during a winter stay in Paris, which should have been his last and - contrary to what was thought - it was.

Aftermath

The principle of the separation of powers found its first expression in 1755 in the constitution of the short-lived republic of Corsica under Pascal Paoli , which went under in 1769 after France had bought the island of Genoa and subjugated it militarily. To this day, however, it was used in the constitution of the United States of America , which came into force in 1787, but not in the French constitution of 1791 . Today, at least in principle, the separation of powers has been achieved in all democratic states.

Montesquieu's theses

His study of the rise and fall of the Roman Empire, published in 1734, formed the basis for his theory of the state. Unlike the Christian philosophy of history, which had viewed the decline of the Roman Empire as the work of divine providence, Montesquieu wanted to find an explanation for the historical processes based on natural laws and therefore had, according to the anthropological, ecological, economic, social and cultural conditions of the political Developments in demand. He shaped these insights into a state and social theory in his main work Vom Geist der Gesetz (1748): He tried to find the determining external and above all mental factors according to which individual states have developed their respective government and legal systems ( culturally relativistic Approach ). The “general spirit” (“esprit général”) of a nation results from these factors, and this in turn corresponds to the “spirit” of its laws. According to Montesquieu, their totality is not a quasi arbitrary sum of laws, but an expression of the natural environment, the history and the “character” of a people.

Montesquieu differentiates between moderate systems of government - that is, the republic in various forms and the constitutional monarchy - and those that are based on tyranny, such as absolutism and every other despotism . He sees the three main types of regimes: republic, monarchy and tyranny, each characterized by a certain basic human attitude: virtue, honor and fear.

For the honor-based constitutional monarchy, but also for the virtue-based form of government , the republic, he considers the separation of powers to be necessary in order to avoid arbitrariness by individuals or teams, otherwise they are in danger of becoming despotic.

Montesquieu's political philosophy contains liberal and conservative elements. He does not equate moderate systems of government, but expressly favors the parliamentary monarchy based on the English model. The model implemented there of a separation of powers between the executive and legislative branches best safeguards the freedom of the individual from state arbitrariness. He supplements this approach by John Locke with a third authority, the judiciary. He also advocates a bicameral parliament with an aristocratic upper house, not only for the monarchy, but also for the republic. This is to prevent the constitutional monarchy from becoming tyranny and the republic becoming “ mob rule ”.

It is disputed whether his theory already established a democratic state or - which represents a minority opinion - rather aimed at restoring the political rights of the nobility and the high courts of law, the parliament, which had been removed by Richelieu , Mazarin and Louis XIV .

While today's sociologists consider Montesquieu to be a pioneer of the modern social sciences (keyword: milieu theory ), his thoughts were evaluated differently by authors and trends immediately following him: The principle of the separation of powers is one of the most important foundations of the first constitutions in North America, in the constitution of the first In the French Republic , however, it did not come into play, because it contradicted the Jacobean , Jean-Jacques Rousseau- inspired doctrine of undivided popular sovereignty , which is why even Montesquieu's grave was destroyed in the French Revolution .

Montesquieu also had an early influence on the Enlightenment in Germany . For example, the proto-sociological author Johann David Michaelis , who was important at the time, followed in his footsteps with the book The Mosaic Law , in which he analyzed certain Old Testament legal provisions that were regarded as absurd by the Enlightenment as reasonable for nomadic peoples - to the annoyance of some clergymen and theologians who a defense of the Bible from this side were little appreciated. In addition to Rousseau's, Johann Gottfried Herder also received Montesquieu's theses for his philosophy of history.

Conditions and limits of action

One can distinguish two main features in the social and political thought of Montesquieu. On the one hand, Montesquieu wants to gain insights into human activity. He is one of the first modern action theorists . On the other hand, he speaks in his entire work of social conditions that are given to politics and the rulers, limit and restrict people's options for action, so that social and historical developments can only be influenced little. According to Montesquieu, politics and society can be inferred from the “esprit général” (general spirit) of a people and the principles of its constitution. In his main work in 1748, he analyzed in detail and as a model the contemporary English constitution, the distribution of power that it entailed, alliances to increase power, but also power limitations.

The basic idea of this model - one can direct the worst human passions (in the case of the English constitution: the uninhibited striving for power) through intelligent institutional arrangements for the benefit and benefit of society - can also be found in his analysis of the modern societies (all monarchies) of his time. The common negative passions of people in the monarchy - ambition, greed, vanity, selfishness, and lust for fame - are channeled through the rules and institutions of a constitutional monarchy in such a way that they work to the benefit of society. His theory of action thus relates primarily to the activities for the introduction of these institutions.

Montesquieu's work is shaped by the search for the conditions, limits, influencing factors and possibilities of human action in society and history. In his theory of action, which is the center of his concept of freedom, he includes the barriers of social action in society.

He collected his thoughts and ideas in thick notebooks. In these notes, the pensées , he states: Complete freedom is an illusion. In many variations he uses the image of a gigantic net in which fish move without realizing that they are trapped in the net. For Montesquieu, action is always subject to conditions that are given to the agent.

Already in the Lettres Persanes ( Persian letters ), especially in the parable of the “Troglodytes”, a concept of freedom can be recognized, which is primarily based on freedom of action. This freedom, which is always in jeopardy, is to be realized in the republic on the basis of patriotism and the “virtue” of the citizens (that is, of just and sensible conduct). The monarchy is less dependent on the virtuous behavior of its citizens and is best governed by the king through laws and institutions.

What is only hinted at in the mentioned novel is the focus of the investigation in the first major work: In the Considérations sur les Causes de la Grandeur des Romains et de leur Décadence ( considerations on the causes of the greatness of the Romans and their decline ), published in Lausanne 1749, Montesquieu describes the martial virtues of the Romans as the most important condition for the successful conquest of the Roman Empire, which finally comprised the entire known world. Although the conquest of the Romans and some peculiarities of the Roman constitution can be traced back to climatic and topographical conditions, according to Montesquieu, the decisive factor for the rise and fall of Rome is the change in Roman virtue, which both enables the conquest of the world and causes its decline.

Guiding principles: virtue, honor and fear

These considerations, his search for the determinants and for freedom of action, reappear in a more systematic form in the main work De L'Esprit des Lois . In this work, Montesquieu's question about the principles of action leads to a new categorization of political orders: the distinctions are no longer determined by the classic question of the number and quality of those in power. Montesquieu distinguishes between moderate and tyrannical governments and names three possible forms of government: republics, monarchies and despotism, each of which he classifies by principles, that is, by different motives and passions, which determine the actions of people in the respective society.

In republics, power and action are distributed in society. In order not to break this order, citizens must develop a high degree of responsibility for the community. It is necessary that they respect each other and subordinate their actions to the common good: "[...] the constant preference of the public interest over their own interest", the love for the equality of the common ruling citizens and the patriotism describe the principle of the republics without that they are not viable. Montesquieu calls this guiding principle "virtue". This "virtue" is to be distinguished from the concept of virtue, which has served as a criterion for the quality of a political order since Plato and Aristotle .

Montesquieu divides the republics into democratic republics, in which the whole people participate in important decisions and in the allocation of offices, and into aristocratic republics, where politics is carried out by a political class. In order for the latter to remain stable, the respective ruling political class must distinguish itself through particular moderation and fairness towards the ruled.

Unlike in the republics, in which equality prevails among those who determine public life and who therefore have to or should moderate themselves on their own, inequality shapes the character of the monarchies. The monarch, the nobility necessary for government, the estates, the provinces, the cities have their place in this order. They strive for reputation and prestige. Everyone wants to excel, the main principle is honor.

The action-guiding striving for prestige and to excel, causes through the ruse of reason of this principle of honor that although all, seeking their advantage, make great efforts, are kept in check by the royal laws and guided in such a way that they are despite selfishness contribute to the common good.

“Honor sets all the members of the political body in motion; it connects them through their own actions, and everyone contributes to the common good in the belief that they are pursuing their own interests. "

The moderation that emanates from the citizens themselves in the republic is thus achieved in the monarchy from outside through institutions and institutional arrangements.

These considerations of Baron are marked by the great impression was reading a book on his thinking: The social theorist Bernard Mandeville was in 1714 in his book The Fable of the Bees ( The Fable of the Bees ) describes how a strange interaction of individual vices by rules can be diverted for the benefit of society. Far before Adam Smith , the father of classical economics , he developed a doctrine of vice of economic good behavior, according to which greed, avarice, indulgence, egoism, extravagance and other vices, regulated by the institutions of market competition, work for the benefit of society. The subtitle of the bees' fable , Private Vices - Public Benefits , expresses this interpretation of the market. Montesquieu has largely adopted these theses and can almost completely dispense with civic virtues in his social model of a constitutional monarchy. The market itself guides virtuous behavior for the benefit of society in socially acceptable channels.

In the third form of government, despotism, human action or non-action is determined by the principle of fear. There is only moderation where customs and habits are stronger than the power of the tyrant. He has to take into account, for example, the religious convictions of his subjects. Basically, however, the despotism is excessive. The entire apparatus of rule, the hierarchy of rulers, are shaped by fear in their actions as are the people and the despot himself. Since there is no legal security that goes beyond the will of the supreme ruler (the will of the despot is supreme law) everyone has to do fear his life, his wealth, his family and his offices. Even the ruler himself can be overthrown by a palace revolt at any time, nothing is safe and this uncertainty applies to everyone. The regime is unstable per se.

In economic matters, despotism is the counterpart of the institutional monarchy. While trade and free trade flourish in an orderly and moderate monarchy, the principle of despotism, fear, ruins economic life. The general uncertainty that characterizes this regime prevents any long-term planning by the citizens. “In such states nothing is improved or renewed: the houses are only built for a human life; you don't drain the soil, you don't plant trees; you exploit the earth but you don't fertilize it, ”writes Montesquieu in The Spirit of Laws . All those involved in the economic process want to be independent of the visible development. A shadow economy is the direct result. Loans are given clandestinely because they are fed from savings and accumulations of money that are hidden from public authority. From this arises usury . Larger possessions are hidden from those in power as well as their helpers and officials - this is the only way they are safe from confiscation . There is only one economic behavior oriented towards short-term needs; everything else is organized in secret. A general rotting of the economy, insofar as it is not pursued by the ruler or for the ruler, is the visible peculiarity of the economy under despotism. There is no such thing as free trade.

Territorial expansion and constitutions

The republics, the monarchies and the despotisms differ in their institutional arrangements and, above all, in their size.

Republics with popular or aristocratic rule are only conceivable for Montesquieu on a small territory, similar to the ancient city republics. If they want to last, they should be characterized by simplicity, relative poverty and simple institutions. A senate, people's assemblies, precisely defined electoral regulations and a clear distribution of responsibilities should exist as well as great respect for the incumbents and strict morals that carry the rules of order into households and families.

Monarchies, on the other hand, can exist on a larger territory without endangering their existence. The monarch needs the nobility, the classes and a power-distributing constitution that also regulates the representation of the classes and classes. The only semi-sovereign king shares the government and administration of the country with the nobility and the estates. Decentralization and local diversity are the direct consequences of this order, which can grant and secure freedoms for citizens just as the republics.

Despoties, which are determined by the despot's arbitrariness, maintain the state order only through a system of mutual fear and can also encompass large territories. A monarchy whose territory is growing oversized can easily degenerate into despotism. Since everything is subordinate to the needs of the sole arbitrary ruler, this can appoint agents (vezire) to represent his power. The Vezir in turn entrusts sub-Vezirs with certain tasks or with the government of certain provinces. The delegation of power is complete, but can just as quickly be completely withdrawn. "The Vezir is the despot himself, and every official is a Vezir," says the fifth book of Esprit des Lois . The constitution of this injustice state consists only in the (fluctuating) will of the despot.

Prosperity through free trade, dangers of the "trade spirit"

For Montesquieu, increasing the prosperity of a people who allow and practice free trade is out of the question, but he also sees dangers if the “trading spirit” is too developed.

He turned against all in his eyes pointless and obstructive trade restrictions. It is “[the] natural effect of trade [...] to bring peace. Two peoples who trade with one another make themselves dependent on one another: if one is interested in buying, the other is interested in selling; and all agreements are based on mutual needs. ”Trade increases prosperity and removes disruptive prejudices . At the beginning of the second volume of his main work, he writes that “the rule is almost generally that where there is gentle morality, there is also trade and that wherever there is trade, there is also gentle morality”. However, too much of the commercial spirit destroys the civic spirit, which prompts the individual “not always to insist rigidly on his claims, but also to put them back in favor of others”, because one sees, continues Montesquieu, “that in the countries where one is only inspired by the commercial spirit, one is also traded in all human actions and all moral virtues: even the smallest things that humanity commands are only done or granted there through money ”.

Warning of extremism and disorder, a plea for stability and moderation

Montesquieu turned against any extreme, non-moderate form of government based on the fear and horror of the subjects against the almost all-powerful despot and his helpers. He feared that the increasingly absolutist ruling princes of Europe could become despots, and therefore made extensive and complicated considerations about mixed constitutions between democratic and aristocratic institutions as well as about different types of republican and monarchical systems in order to create the conditions for stable and secure orders in which one free civil existence is possible in his view.

The political and social thinking of the enlightener and aristocrat Montesquieu must not only be viewed against the background of intellectual and cultural history, but also the crises and upheavals of his time. With the Edict of Nantes in 1598, the bitter religious civil war in France ended. The long period of absolutism in its pure form under Louis XIV , which brought the country a great power position, but also devastating wars, concentration of power on one person and his vassals and ultimately even the withdrawal of the Edict of Tolerance of Nantes in 1685, was from the 1715 unstable régence and later government of the much weaker Louis XV. been replaced.

Europe was a truce religious battlefield at the time of Montesquieu. The colonization of the rest of the world had begun, world trade and later industrialization were emerging. Philosophy and natural sciences unfolded on the one hand in the sense of reason and experience, on the other hand there were defensive battles of the old rule with many losses. The individual protagonists of different worldviews sometimes fought each other mercilessly. Montesquieu opposed the radical ideas of a large number of French encyclopedists in particular with an enlightened, yet conservative, moderate political approach. The politician, philosopher and traveler, who wrote on his major work Vom Geist der Gesetz (The Spirit of Laws) for years , responded to the confrontations of his time with a warning against despotism and tyranny and a plea for moderate, stable forms of government that give citizens (always limited) freedoms enable.

For Montesquieu, freedom does not consist in doing everything you want, rather freedom is primarily the fulfillment of what is necessary and what you are obliged to do.

The “general spirit” of a people, protection of public order as a prerequisite for tolerance and freedom

He warns the rulers of megalomania. The “general spirit” (“esprit général”) of a people, slowly grown in the process of history, shaped by the landscape and the climate, influenced by religion and at the same time forming religion, permeated by the principles of the existing constitution, by historical models, examples and determines habits, customs and morals, represents the essential basic substance of a society. Although this spirit is not an immutable quantity, according to Montesquieu it should only be influenced very carefully. He cannot be completely manipulated, since even despots have to respect the religious convictions of their subjects in some way. Trade with foreign peoples, for example, changes morals, frees you from prejudices and leads to greater prosperity, but the general spirit of a people is only affected within narrow limits.

In summary he writes: “Constitutional rules, penal laws, civil law, religious regulations, customs and habits are all interwoven and influence and complement one another. Anyone who makes rash changes endangers his government and society. "

Accordingly, Montesquieu pleads for religious tolerance. If there is only one religion in the respective society, no other should be introduced. Whereas several exist side by side, the ruler should regulate the coexistence of followers of different religions. The institutional stability makes many penal provisions superfluous.

Punishments are only intended to protect public goods. Privacy can be regulated on the basis of recognition of differences. Religious controversies are generally not to be prosecuted legally. The punishment of religious outrages should be left to the offended God. The prosecution of worldly crimes is a sufficiently busy activity for the judicial authorities. Montesquieu rejects the then self-evident persecution of homosexuals as well as the punishment of other behaviors of the most varied kinds, if they do not disturb the public order that makes this tolerant attitude possible.

About separation of powers

The concept of the separation of powers has already been presented in full by Aristotle and - contrary to popular and even professorial opinions - it was not Montesquieu as the author. The latter writes about the separation of powers. a. in his central work Vom Geist der Gesetz , 1748: Freedom only exists when the legislative, executive and judicial branches are strictly separated from each other in a moderate system of government, otherwise the coercive force of a despot threatens. To prevent this, the rule of thumb is that the power of power must set limits (“Que le pouvoir arrête le pouvoir”).

- "As soon as the legislative power is combined with the executive in one and the same person or the same civil service, there is no freedom."

- “There is also no freedom if the judicial authority is not separated from the legislative and executive authority. Power over the life and liberty of the citizens would be absolute if that were coupled with legislative power; for the judge would be a legislator. The judge would have the coercive power of an oppressor if that were coupled with executive power. "

- "Everything would be lost if one and the same man or the same body, either of the most powerful or of the nobles or of the people, exercised the following three powers: enact laws, implement public resolutions, judge crimes and private disputes."

- “Democracy and aristocracy are not inherently free forms of government. Freedom is only found under moderate governments. Experience teaches that anyone who has power tends to abuse it. Therefore it is necessary that the power of power set limits. There are three types of authority in every state: the legislative, the executive and the judiciary. There is no freedom if these are not separated from each other. "

Works

- De l'esprit des loix ( 1748 ), dt. From the spirit of laws . Reclam, 1994, ISBN 3-15-008953-0 .

- On the Spirit of Laws I and II (selected, translated and approved by Friedrich August von der Heydte , de Gruyter, Berlin 1950; edited and translated by Ernst Forsthoff , Laupp, Tübingen 1951 (UTB 1710) ).

- Lettres persanes ( 1721 ), German Persian letters . Reclam, 1991, ISBN 3-15-002051-4 .

- Histoire véritable d'Arsace et Isménie ( 1730 ), German true story . Structure Tb, 1997, ISBN 3-7466-6010-6 .

- Le Temple de Gnide ( 1725 ).

- Considérations sur les causes de la grandeur des Romains et de leur décadence . Lausanne 1749, German considerations on the causes of the greatness of the Romans and their decline. Lausanne 1749.

- Essai sur le goût dans les choses de la nature & de l'art . In: Encyclopédie ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers , Vol. 7, Paris 1757, pp. 762–767.

- Considérations sur les causes de la grandeur des Romains et de leur décadence , German size and decline of Rome , Amsterdam 1734. a. Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag Frankfurt / Main 1980, ISBN 3596234328 .

- Oeuvres Complètes (ed.Caillois) Pléiade, Paris 1949.

- Oeuvres Complètes (ed.Masson), Paris 1950.

- Jürgen Overhoff (Ed.): My travels in Germany 1728–1729 . Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2014, ISBN 978-3-7681-9900-1 .

See also

- List of French writers

- Hannah Arendt , who refers heavily to Montesquieu in her political theory

- Asteroid (7064) Montesquieu

Individual evidence

- ^ Entry on Montesquieu, Charles de Secondat (1689–1755) in the Archives of the Royal Society , London .

- ↑ Among other things, Montesquieu had dealt with the theses of the Italian cultural and legal philosopher Giambattista Vico .

- ↑ Pierre Gros Claude: Un audacieux message. L'encyclopédie . Nouvelles Editions Latines, Paris 1951, p. 121 ( google.com [accessed August 28, 2015]).

- ↑ See The Spirit of Laws , Book XI, chap. 6th

- ↑ See The Spirit of Laws , Book XI, chap. 3.

- ↑ See The Spirit of Laws , Book XI, chap. 6th

literature

- Effi Böhlke, Etienne François (ed.): Montesquieu. French, Europeans, citizens of the world . Academy, Berlin 2005, ISBN 978-3-05-004165-0 .

- Claus-Peter Clostermeyer: Two faces of the Enlightenment. Tensions in Montesquieu's "Esprit des Lois". Berlin 1983.

- Louis Desgraves: Montesquieu . Societäts, Frankfurt 1992, ISBN 3-7973-0497-8 .

- Martin Drath : The separation of powers in German constitutional law. In: Heinz Rausch (Ed.): On today's problem of the separation of powers. Darmstadt 1969, pp. 21-77.

- Berthold Falk: République fédérale d'Allemagne. In: Société Montesquieu (ed.): L'État et la religion. Colloque de Sofia 2005, Sofia 2007

- Ders .: Montesquieu . In: Hans Maier , Horst Denzer (ed.): Classics of political thinking. 2nd volume. 3. Edition. Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-406-56843-5 .

- Ders .: Montesquieu and the Count of Daun . In: Paul-Ludwig Weinacht (ed.): Montesquieu. 250 years of the “Spirit of Laws”. Baden-Baden 1999.

- Jean Firges : Montesquieu: “The Persian Letters” . Exemplary series literature and philosophy, volume 21. Sonnenberg, Annweiler 2005, ISBN 978-3-933264-41-1 (interpretation).

- Michael Hereth: Montesquieu as an introduction . Panorama, Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 3-926642-59-9 .

- Heike Jung: Montesquieu and criminal policy . JuS 1999, pp. 216-220.

- Horst Wolfgang Karkossa: Baron de Montesquieu. In: Ed Randall, Duncan Brack (Eds.): The Dictionary of Liberal Thought . Methuen, London 2007.

- Victor Klemperer : Montesquieu (habilitation). Volume I (1914) and Volume II (1915) at Archive.org .

- Gottfried Koch: Montesquieu's constitutional theory . Completed and improved by Klaus H. Fischer. Scientific publishing house, Schutterwald 1998, ISBN 978-3-928640-17-6 .

- Edgar Mass (ed.): Montesquieu Traditions in Germany. Contributions to the study of a classic. Berlin 2005.

- Alois Riklin : Montesquieu's liberal state model. In: Political quarterly . No. 30, pp. 420-442.

- Jean Starobinski : Montesquieu . Seuil, Paris 1953 (Ger. Montesquieu. Thinking and Existence . Hanser Verlag 1986, ISBN 3-446-13959-1 ).

- Helmut Stubbe da Luz : Montesquieu. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1998, ISBN 3-499-50609-2 .

- Robert Hugo Ziegler: The place of power remains empty, or: Politics in the Seraglio: Montesquieu . In: Same: Constellations. Studies in politics and metaphysics . K&N, Würzburg 2018, ISBN 978-3-8260-6519-4 , pp. 221–301.

Web links

- Literature by and about Charles de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Charles de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu in the German Digital Library

- Works by Montesquieu in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Montesquieu on the Internet Archive

- Entry in Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

- On the Spirit of Laws (excerpts) ( Memento of 23 August 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- Article in "Name, title and dates of the French. Literature " (source for the section" Life and Creation ")

- Short biography and list of works of the Académie française (French)

- Time signal : 01.18.1689 - the philosopher Montesquieu Birthday

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Montesquieu, Charles de Secondat Baron de |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | La Brède et de Montesquieu, Charles-Louis de Secondat Baron de |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French writer and state philosopher |

| DATE OF BIRTH | baptized January 18, 1689 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | La Brède Castle near Bordeaux |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 10, 1755 |

| Place of death | Paris |