Chang'e-3

| Chang'e-3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSSDC ID | 2013-070A | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mission goal | Earth moon | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Client | CNSA | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Launcher | CZ-3B | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Course of the mission | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Start date | December 1, 2013, 17:30 UTC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| launch pad | Xichang Cosmodrome | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

Chang'e-3 ( Chinese 嫦娥 三號 / 嫦娥 三号 , Pinyin Cháng'é Sānhào ) is the third lunar probe of the China National Space Administration (CNSA) as part of the lunar program of the People's Republic of China . The two predecessor probes Chang'e-1 and Chang'e-2 were orbiters , Chang'e-3 landed successfully on the moon and set down the moon rover Jadehase (Yutu, 玉兔 ). The Chang'e 3 lander is still active and providing data.

The names refer to the Chinese moon goddess and her companion .

Mission history

On December 1, 2013, aboard Chang'e-3 launched a missile of the type Long March 3B from the Xichang Satellite Launch Center in Earth orbit. 20 minutes after the launch, the probe separated from the rocket. The probe swiveled out of orbit into a transfer orbit. The swing into a lunar orbit on December 6th was prepared with three corrective maneuvers, after a braking maneuver a circular orbit around the moon with an altitude of 100 km was reached. After lowering the periselenum to 15 km, the landing was initiated by another braking maneuver. During the last 12 minutes of the descent, the probe then acted completely autonomously and independently looked for a suitable landing site.

Landing position of Chang'e-3 on the lunar surface |

The soft landing took place on December 14 at 13:11:18 UTC, one orbit earlier than originally planned and thus 250 km east of the Sinus Iridum in the Mare Imbrium at 44.115 ° N 19.515 ° W. Live images of the descent were transmitted. Six hours later the rover (mass 140 kg) left the lander via a ramp. To generate energy on lunar nights, Chang'e-3 has a radioisotope generator on board, which is supported on lunar day by energy from the two solar panels. The moon rover Jadehase only has solar panels and does not work during the moonlit nights. He has a radionuclide heating element on board to protect against the cold at night .

To support the probe, China worked with ESA , which provided the ESTRACK antenna network for receiving the radio signals and for the flight phase . The ESA also helped to determine the position during the landing. China now has enough of its own facilities to operate the probe.

On December 25, 2013, the APX spectrometer (Active Particle-induced X-ray Spectrometer) of the moon rover Yutu was used for the first time to determine the chemical composition of the moon's surface. It is an X-ray spectrometer that determined the percentage chemical composition of rocks and lunar regolith using X -ray fluorescence spectroscopy and particle-induced X-ray emission ( PIXE ).

Between January 27 and February 13, 2014, media reports appeared about malfunctions of the rover Yutu and problems with reactivating it after the second lunar night. However, it was possible to re-establish contact with the device. On March 10, 2014, after the third lunar night, Yutu reported again from his permanent position.

On August 3, 2016 it was announced that the Jade Bunny finally wishes "good night". Although Yutu was designed for only three months, the rover explored the moon for 31 months.

The Luna-based Ultraviolet Telescope (LUT) of the National Astronomical Observatories of the Chinese Academy of Sciences on the lander, however, is still active (as of June 2020). Since it is built into a chamber to protect against the electrostatically charged lunar dust, the hatch of which is closed at sunrise and sunset - lunar dust rises increasingly at light-dark borders - so far there have been no dust deposits on the mirrors of the Ritchey-Chrétien-Cassegrain Telescope . The 238 Pu in the lander's radionuclide battery should last for about 30 years, and unless unforeseen incidents occur, astronomers could make their observations in the near-ultraviolet range (400-300 nm) during this entire time .

For the Chang'e 3 mission, the TT&C system of the lunar program was expanded in the years 2009–2012 so that the military deep-space stations at Kashgar and Giyamusi - only the People's Liberation Army is authorized and able to send control signals to Chinese spacecraft to send - address two different targets with a wave packet, so you can control the lander and rover at the same time. The viewing angle of the ultraviolet telescope can be changed by a flat mirror that is mounted at a certain distance in front of its light incidence opening and freely pivotable via a cardanic suspension . When the astronomers want to examine a certain object in space, they inform the deep-space stations via the Xi'an satellite control center , which then issue the appropriate control commands. The AIMO CCD sensor manufactured by the British e2v (formerly English Electric Valve Company , since 2017 Teledyne e2v ) sends the recorded images whenever there is visual contact with China to the civilian ground stations in Miyun and Kunming , which are assigned during the lunar missions receive the downlink traffic of the scientific payloads.

Results

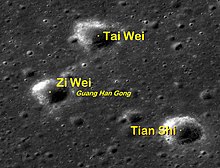

Through the spectrographic recordings of the lunar surface taken in 1994 by NASA's Clementine probe , in 1998/99 by Lunar Prospector (also NASA), in 2008/2009 by Chandrayaan-1 of the Indian Space Research Organization and above all by Chang'e-1 and Chang'e-2 , one had a pretty good idea of the mineralogical composition of the upper layers of the moon. The landing site of Chang'e-3 was carefully chosen on the edge of a small, only 27-80 million year old (i.e. relatively fresh) crater with a diameter of about 450 m, where the meteorite impact at the time came to the surface from a depth of 40-50 m had hurled. On the east side of this crater, officially called Zǐwēi (紫微, literally “Purple Forbidden Area”, meaning “Area of the Imperial Palace”) since October 5, 2015 , the Rover Yutu covered a total of 114 meters. During its journey, the Jade Hare approached the crater rim on a more or less J-shaped course, stopping 8 times, in addition to the occasional photo-stop, to take measurements. After the first evaluations of the data he provided, his ground penetrating radar measured a two to three meter thick regolith layer , followed by a 41 to 46 meter thick basalt layer with a striking amount of titanium oxide. Beneath this, within the measuring range of 140 meters depth, lies a second basalt layer with a different composition.

Particularly interesting are the results of the spectrographic recordings that the rover made at four points from with the help of its infrared spectrometer ( Visible and Near-infrared Imaging Spectrometer or VNIS) and its alpha particle X-ray spectrometer ( Active Particle-induced X-ray Spectrometer or APXS) the lunar surface made. The main elements iron , titanium , magnesium , aluminum , silicon , potassium and calcium as well as some trace substances were detected. The percentage composition of the soil in terms of ferrous oxide (extremely high), calcium oxide (high), titanium dioxide (medium), aluminum oxide (little) and silicon dioxide (very little) was in stark contrast to the soil samples obtained by The Apollo astronauts were brought back to Earth, but corresponded to what the researchers around Ling Zongcheng (凌宗成) from the Institute for Space Science at Shandong University expected after the images made by the previous probes from the lunar orbit for this place. This showed the usefulness of area-wide long-range reconnaissance using orbital probes and proved their reliability.

The landing site was officially named Guǎnghán Gōng ( 廣寒宮 / 广寒宫 - “Palace of the Wide Cold”) on October 5, 2015 , after the moon palace in Chinese mythology, where Chang'e and Yutu lived.

The determination of the hydroxyl radical density in the very thin atmosphere or exosphere of the moon brought a rather unpleasant result . Wang Jing (王 竞) from the Xinglong Station of the National Astronomical Observatories of the Chinese Academy of Sciences , together with several colleagues, analyzed the spectrum of the background in 498 images taken by the Luna-based Ultraviolet Telescope (LUT) during the lunar days of bright stars as Thuban , Kochab etc. had recorded. The spectral line of the OH radical, which is created by the impact of ultraviolet radiation on water molecules generated by the solar wind, is at 308.7 nm, i.e. in the observation range of the CCD sensor in the 15 cm telescope. After processing the data and eliminating sources of error, Wang Jing's group came to the conclusion that there are fewer than 10,000 hydroxyl radicals per cubic centimeter in the exosphere of the moon, i.e. 2 orders of magnitude less than the 1,000,000 radicals that are found at Remote observations with the Hubble Space Telescope found, and 6 orders of magnitude less than what the Indian Chandrayaan-1 moon orbiter found. This means that there is, at least in the Palace of the Wide Cold, significantly less water on the moon than previously assumed.

With a quartz crystal microbalance mounted on the lander developed by Yao Rijian (姚 日 剑), Wang Yi (王 鹢) and others in 2009 at the Research Institute 510 (Physics) of the Chinese Academy of Space Technology in Lanzhou , the amount of Moondust deposited on the probe was measured, funded by the National Foundation for Natural Sciences and, from 2016, by the Weapons Development Department of the Central Military Commission . After a thorough analysis and consideration of the special features of the lander, the scientists of the moondust research group at Institute 510 (510 所 月 尘 测量 技术 研究 团队) published their results in the Journal of Geophysical Research : Planets on August 2, 2019 . At a height of 190 cm above the lunar surface in the northern Mare Imbrium , 0.0065 mg of lunar dust per square centimeter was deposited on the immobile lander during twelve lunar days (that is, “blown up” by the solar wind), which corresponds to an annual deposition rate of around 21.4 μg / cm². This was the first time that such long-term measurements were carried out directly on the lunar surface (and not from orbit). The data obtained will now be incorporated into the dust protection measures for future lunar probes at the Chinese Academy for Space Technology.

By January 2016, 35 gigabytes of image material that had been recorded with the cameras of Lander and Rover had been published.

See also

- List of space probes

- Chronology of the moon missions

- Space of the People's Republic of China

- List of man-made objects on the moon

literature

- Chang'e-3. In: Bernd Leitenberger: With space probes to the planetary spaces: New beginning until today 1993 to 2018 , Edition Raumfahrt Kompakt, Norderstedt 2018, ISBN 978-3-74606-544-1 , pp. 357–362

Web links

- Günther Glatzel: Scientific equipment from Chang`e 3. In: raumfahrer.net. December 3, 2013, accessed December 4, 2013 .

- Bernd Leitenberger: Chang'E December 23, 2013, accessed May 18, 2014 .

- Radio China International : China's space travel in focus, excerpt from the press conference for the Chang'e-3 mission with Wu Weiren, chief designer of the Chinese lunar program. December 19, 2013, accessed January 5, 2014 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Worldwide Launch Schedule. Spaceflight Now, November 27, 2013, accessed November 28, 2013 .

- ↑ Leonard David: China Reading 1st Moon Rover for Launch This Year. space.com, June 19, 2013, accessed July 19, 2013 .

- ↑ Space travel: Chinese probe is scheduled to land on the moon in 2013. spiegel.de, August 29, 2013, accessed on August 29, 2013 .

- ↑ Launch of the Chinese lunar probe Chang'e-3. Radio China International, December 2, 2013, accessed December 1, 2013 .

- ↑ Martin Holland: China's moon landing mission started successfully. heise online, December 2, 2013, accessed on December 3, 2013 .

- ↑ China launches 'Jade Rabbit' rover on first moon landing mission. collectSPACE, December 2, 2013, accessed December 3, 2013 .

- ^ Günther Glatzel: Chang'e 3 on the way to the moon. Raumfahrer.net, December 1, 2013, accessed December 3, 2013 .

- ↑ 孙泽洲 从 “探 月” 到 “探 火” 一步 一个 脚印. In: cast.cn. October 26, 2016, Retrieved May 10, 2019 (Chinese).

- ↑ CCTV live report from the landing ( memento of the original from December 15, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b heise online: China's rover "Jadehase": Hundreds of photos of the moon published. In: Heise Online. Retrieved January 29, 2016 .

- ↑ Images of the descent camera

- ↑ Video from leaving the lander, CCTV

- ↑ Gunter's Space Page: Chang'e 3 (CE 3) / Yutu. Retrieved December 23, 2013.

- ↑ Spaceship "Chang'e 3" launched. China gives the go-ahead for first moon landing. RP-online, December 1, 2013, accessed December 1, 2013 .

- ↑ Ralph-Mirko Richter: Moon rover Yutu delivers first scientific data. Raumfahrer.net, January 6, 2014, accessed January 6, 2014 .

- ↑ Zhang Hong: Jade Rabbit moon rover may be beyond repair, state media hints. South China Morning Post, January 27, 2014, accessed January 27, 2014 .

- ↑ China's moon rover "Jadehase" is broken. ( Memento from February 26, 2014 in the Internet Archive ). In: 02elf Abendblatt. 12th of February 2014.

- ↑ dpa , Xinhua : China's "Jade Bunny" revived on the moon. Heise online , February 13, 2014, accessed on February 13, 2014 .

- ^ Günther Glatzel: Yutu is sending again. Raumfahrer.net, February 13, 2014, accessed February 13, 2014 .

- ↑ a b Jadehase Yutu delivers first scientific results. In: Stars and Space . 5/2014, pp. 14-15 ( online ).

- ↑ Fans mourn the loss of the Chinese moon vehicle “Yutu”. At: orf.at. August 3, 2016, accessed August 3, 2016.

- ^ Lunar-based Ultraviolet Telescope (LUT). In: nao.cas.cn. Retrieved December 12, 2019 .

- ^ Wang Jing et al .: 18-Months Operation of Lunar-based Ultraviolet Telescope: A Highly Stable Photometric Performance. In: arxiv.org. October 6, 2015, accessed May 17, 2019 .

- ↑ Helga Rietz: Floating dust on the moon. In: deutschlandfunk.de. August 1, 2012, accessed May 17, 2019 .

- ^ Ralph L. McNutt: Radioisotope Power Systems: Pu-238 and ASRG status and the way forward. In: lpi.usra.edu. January 8, 2014, accessed May 17, 2019 .

- ^ A b Andrew Jones: China's telescope on the Moon is still working, and could do for 30 years. In: gbtimes.com. June 5, 2017, accessed May 17, 2019 .

- ↑ Wang Jing et al .: Photometric Calibration on Lunar-based Ultraviolet Telescope for Its First Six Months of Operation on Lunar Surface. In: arxiv.org. December 12, 2014, accessed May 23, 2019 .

- ↑ See CCD42-10 Back Illuminated High Performance AIMO CCD Sensor. In: e2v.com. Retrieved May 23, 2019 .

- ↑ 40 米 射 电 望远镜 介绍. In: ynao.cas.cn. January 6, 2012, accessed May 23, 2019 (Chinese).

- ↑ a b Ling Zongcheng et al .: Correlated compositional and mineralogical investigations at the Chang′e-3 landing site. In: nature.com. December 22, 2015, accessed May 2, 2019 .

- ↑ Term "Ziwei - 紫微". In: www.zdic.net. Retrieved June 18, 2019 (Chinese).

- ↑ term "Ziweiyuan -紫微垣". In: www.zdic.net. Retrieved June 18, 2019 (Chinese).

- ↑ 黄 堃: “嫦娥” 落月 之 地 真 成了 “广寒宫”. In: xinhuanet.com. November 12, 2015, accessed May 2, 2019 (Chinese).

- ↑ Zi Wei. In: planetarynames.wr.usgs.gov. October 5, 2015, accessed May 2, 2019 .

- ↑ The name is derived, like that of the two craters in the neighborhood, from the " Three Areas " (垣, Pinyin Yuán ), a term that has been in use at least since the spring and autumn period for regions of the sky that originally had one low earth wall not unlike a crater wall delimited city district meant. The syllable Wēi (微) specifies this area as “hidden from the public”, and the earthen walls (later walls) were marked as belonging to the ruling family with purple color or red clay (紫, Pinyin Zĭ ). Therefore, "Ziwei" has also been used as an expression for the palace of a member of the imperial family or liege prince since the Tang Dynasty . Since the Jade Emperor does not live on the moon, but in the heavenly palace , the crater is simply a demarcated area that is not accessible to ordinary people. 罗 竹 风 (主编): 汉语大词典.汉语大词典 出版社, 上海 1994 (第二 次 印刷). 第二 卷, p. 1093; 第三 卷, p. 1049; 第九卷, p. 820.

- ^ Mike Wall: The Moon's History Is Surprisingly Complex, Chinese Rover Finds. On: space.com. March 12, 2015.

- ↑ Xiao Long et al .: A young multilayered terrane of the northern Mare Imbrium revealed by Chang'E-3 mission. In: science.sciencemag.org. March 13, 2015, accessed March 15, 2020 .

- ↑ 高 层次 人才. In: apd.wh.sdu.edu.cn. September 7, 2018, accessed May 3, 2019 (Chinese).

- ↑ Nadja Podbregar: Unknown moon rocks. In: Wissenschaft.de. December 22, 2015, accessed May 2, 2019 .

- ↑ Guang Han Gong in the Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature of the IAU (WGPSN) / USGS

- ↑ 中国科学院 大学 王 竞 研究员: 月 基 天文 与 伽玛 暴 , 黑洞. In: phys.obenu.edu.cn. November 14, 2017, Retrieved May 17, 2019 (Chinese).

- ↑ Heike Westram: Eternal ice in icy craters. In: br.de. January 17, 2019, accessed May 17, 2019 .

- ↑ Researchers find ice at the lunar north pole. In: zeit.de. March 2, 2010, accessed May 17, 2019 .

- ↑ Wang Jing et al .: An Unprecedented Constraint on Water Content in the Sunlit Lunar Exosphere Seen by Lunar-Based Ultraviolet Telescope of Chang'e-3 Mission. In: arxiv.org. February 15, 2015, accessed May 17, 2019 .

- ↑ Is There an Atmosphere on the Moon? In: nasa.gov. April 12, 2013, accessed May 17, 2019 .

- ↑ 姚 日 剑 、 柏树 、 王先荣 、 王 鹢 、 颜则东: 一种 微小 尘埃 的 测量 方法. In: patents.google.com. June 30, 2010, Retrieved September 21, 2019 (Chinese).

- ↑ 月 尘 测量 仪 : 揭开 月亮 女神 的 神秘 面纱. In: zhuanti.spacechina.com. December 18, 2013, accessed September 21, 2019 (Chinese).

- ↑ Detian Li, Yi Wang et al. a .: In Situ Measurements of Lunar Dust at the Chang'E ‐ 3 Landing Site in the Northern Mare Imbrium. In: Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. 124, 2019, p. 2168, doi : 10.1029 / 2019JE006054 .

- ↑ 我国 科研 人员 成功 实现 对 月球 表面 月 尘 累积 质量 的 测量. In: clep.org.cn. September 20, 2019, accessed September 21, 2019 (Chinese).