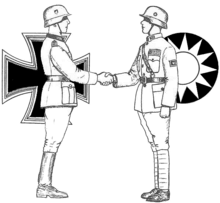

Sino-German cooperation (1911–1941)

The Sino-German cooperation played in Chinese history a big part of the early to mid 20th century.

After the First World War, Germany left China as a colonial power, while other states (Great Britain, France, Japan, the United States) continued to insist on their special rights in China. As a result, Sino-German relations developed on the basis of full equality, in contrast to China's relations with other states. Both Germany and China saw themselves as disadvantaged by an unjust post-war order - Germany because of the restrictions imposed after the lost war, and China because it was denied international equality. As a result, the two states came closer together, based on mutual interests. On the one hand there was the Chinese interest in modernizing the military, in particular, but also economy and administration. Here Germany was often seen as a model for a modern and efficient state. On the other hand, there was German interest in Chinese raw materials and in China as a sales market for German industrial products.

The close cooperation since the 1920s led to the modernization of the Republic of China's industry and military . The cooperation reached its peak in the early 1930s. Despite all the differences, the Kuomintang ruling in China saw National Socialist Germany , which was growing stronger militarily and gradually threw off the shackles of the Versailles Treaty, a model in a certain way, as did China by concentrating national forces on external enemies, especially the increasingly aggressive one occurring Japan could encounter. On the German side, it was undecided which alliance partner to choose in the Far East - China or Japan. In the end, German politics decided in favor of Japan, much to the regret of the Kuomintang government, and cooperation with China was officially discontinued with the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War in 1937. Nonetheless, the cooperation had profound effects on the modernization of China and its ability to resist the Japanese invaders in the war.

Early Sino-German relations

Initially, trade between China and Germany took place overland through Siberia and was subject to Russian transit taxes. To avoid this, Germany decided to use the sea route. In 1751, during the reign of the Qing dynasty, the first trading ships of the Emden “ Royal Prussian Asian Company ” reached China. After China's defeat in the Second Opium War in 1861, the Treaty of Tianjin was signed. This obliged China to open the empire to trade with various European states, including Prussia .

During the late 19th century, China's foreign trade was dominated by the British Empire . Otto von Bismarck tried to get Germany to gain a foothold in China in order to balance British supremacy. In 1885 the Reichstag decided on a bill by Bismarck to subsidize steamships that were supposed to enable direct voyages to China. That same year, the first banking and industrial scouting group was sent to China to evaluate investment opportunities. This led to the establishment of the German-Asian Bank in 1890 . These measures put Germany in second place behind the British in China's trade and shipping statistics in 1896.

During this time Germany did not pursue any active imperialism in China and, in contrast to Great Britain and France, seemed relatively cautious. Therefore, the Chinese government saw Germany as a partner who could help China modernize it. The Chinese government bought two battleships built in Germany , the Dingyuan and her sister ship Zhenyuan, for its navy . After China's first attempts at modernization, followed by the defeat in the first Sino-Japanese war, failed, the politician and military leader Yuan Shikai asked for German help in building the "self-strengthening army " ( Chinese 自強 軍 , Pinyin Zìqiáng Jūn ) and the newly created ones Army (新建 陸軍; Xīnjìan Lùjūn). But the German aid concerned not only the military, but also industry. For example, in the late 1880s , the Krupp Company was commissioned by the Chinese government to build a series of fortifications around Port Arthur .

Under the rule of Wilhelm II , Germany's China policy, which was still relatively benevolent under Bismarck, was drastically changed, primarily because of his imperialist stance. For example, after the first Sino-Japanese war, with the intervention of Shimonoseki , Japan was forced to surrender its concessions in Hankou and Tianjin to Germany. In 1897, Germany also obtained a lease for 99 years on Kiautschou Bay in Shandong after missionaries in this region were attacked by the Chinese. The Boxer Rebellion of 1900, which was bloodily suppressed by the German military after attacks against foreigners, was perhaps the lowest point in Sino-German relations. On the occasion of the departure of German troops to China, Kaiser Wilhelm II gave his notorious Huns speech . This earned the Germans in England the nickname "the Huns", which was also used as a derisive term for German soldiers during the First and Second World Wars.

The development of Chinese law was also significantly influenced by German law during this period. Before the fall of the Qing dynasty, Chinese reformers began to work out a civil code that was largely based on the German Civil Code , which was also adopted in Japan. Although this draft was not promulgated until the collapse of the Qing Dynasty, it was the basis for the Civil Code of the Republic of China, which was introduced in 1930. To this day, it still applies in Taiwan and has influenced the law in mainland China .

Nevertheless, Sino-German relations became less intense in the period before the First World War . One reason for this was Germany's political isolation, which became more and more apparent as a result of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance of 1902 and the Triple Entente of 1907. Therefore, Germany proposed a German-Chinese-American agreement in 1907, which was never implemented. In 1909 the German-Chinese University was founded in Tsingtao , where Sun Yat-sen praised Germany as a model for the new China when he visited in 1912 . In 1912, Germany offered the Chinese government a loan of six million Reichsmarks and resumed the rights to build the Chinese railroad in Shandong. When the First World War broke out in Europe in 1914, Germany offered to return Kiautschou Bay to China to prevent the concessions from falling to Japan. Nevertheless, Japan entered the war on the side of the Allies and continued the attack on German concessions in China. Japan took Kiautschou Bay and Tsingtao. During the war, Germany did not take an active role in the Far East and did not take any initiative in any significant action, as the focus was on the war in Europe. Military missions - such as the planned demolition of the railway by the military attaché in Beijing, Werner Rabe von Pappenheim - were kept as secret as possible and remained the exception.

On August 14, 1917, China declared war on Germany and won the German concessions in Hankou and Tianjin . After the defeat of Germany, China should regain further German areas of influence. With the Treaty of Versailles , however, these concessions went to Japan. The feeling of betrayal by the Allies ignited the May Fourth nationalist movement . As a result, World War I dealt a serious blow to Sino-German relations, particularly trade. For example, of the almost 300 German companies that were based in China in 1913, only two companies had locations there by 1919.

Sino-German cooperation in the 1920s

German industrial production was severely restricted by the Treaty of Versailles. The Reichswehr was limited to 100,000 men, and military production was also extremely restricted. Still, the treaty did not curtail Germany's leadership in military development. Many companies continued to research and manufacture military equipment. In order to continue to legally manufacture and sell weapons and to circumvent the restrictions of the treaty, these companies formed partnerships with other nations such as the Soviet Union and Argentina .

After Yuan Shikai's death in 1916, the central Beiyang government in China collapsed and a civil war broke out, in which various warlords fought for supremacy. As a result, many German arms manufacturers began to try to reestablish commercial ties with China in order to gain a foothold in its broad arms market.

The Kuomintang government in Guangzhou also sought German support, and Chu Chia-hua (朱家 驊; Zhū Jiāhuá), who had studied in Germany, stepped forward. From 1926 to 1944 he was instrumental in organizing almost every Sino-German contact. In addition to German technological progress, there were other reasons that brought Germany back to a leading position in Chinese foreign policy. At first , after the loss of all colonies by the First World War, Germany, including the colonial movement that followed , no longer had any imperialist interests in China. There, the xenophobic protests from 1925 to 1926 were mainly directed against Great Britain. In addition, unlike the Soviet Union, which helped reorganize the Kuomintang party and open it up to communists, Germany had no political interests in China that could have led to a confrontation with the central government. Furthermore, Chiang Kai-shek saw German history as worth emulating, especially in the respect that the unification of the German Empire could be instructive for the unification of China in Chiang's view. As a result, Germany was seen as the main force behind China's international development.

In 1926, Chu Chia-hua invited Max Bauer to China to explore the investment opportunities there. The following year, Bauer arrived in Guangzhou and was offered a job as Chiang Kai-shek's advisor. Bauer returned to Germany in 1928 in order to establish suitable industrial contacts there for China's "reconstruction". He began recruiting for a permanent advisory position with Chiang Kai-shek in Nanking. But Bauer was not entirely successful as many German companies hesitated because of the unstable political situation in China. Also, because of his involvement in the Kapp Putsch of 1920 , Bauer was not exactly respected in Germany. In addition, Germany was still restricted by the Versailles Treaty, which made direct investments in the military impossible. Max Bauer died of smallpox seven months after returning to China and was buried in Shanghai . Nevertheless, for a short time in China, Bauers laid the foundation stone for the later Sino-German cooperation, as he advised the Kuomintang government to modernize industry and the military. He spoke out in favor of downsizing the Chinese army in order to form a small but all the better trained force. He also supported the opening of the Chinese market in order to promote German production and German exports.

Sino-German cooperation in the 1930s

Nevertheless, Sino-German trade was weakened between 1930 and 1932 due to the Great Depression. Furthermore, industrialization in China could not advance as quickly as possible. This was due to a conflict of interests between various Chinese reconstruction companies, German import-export companies and the Reichswehr , all of whom wanted to benefit from China's progress. Until the Mukden incident in 1931, through which Manchuria was annexed by Japan, the development could not be advanced. This incident highlighted the need in China for an industrial policy aimed at directing the military and industry to resist Japan. This led to the establishment of a centrally planned national defense economy being pushed forward from now on. As a result, on the one hand, Chiang's rule over nominally unified China was strengthened, and on the other hand, efforts towards industrialization were increased.

The " seizure of power " by the NSDAP in 1933 accelerated the formation of a concrete German policy on China. Before that, German policy towards China was contradicting itself : The foreign ministers of the Weimar Republic always advocated a neutral East Asia policy and prevented the Reichswehr and industry from interfering too much in the Chinese government. The import-export companies also took this view for fear that direct government agreements would dissuade them from their profitable position as middlemen. The Nazi government now pursued a war economy policy that demanded all raw material supplies that China could supply. In particular, the militarily important raw materials such as tungsten and antimony were in demand in large numbers. Hence, from now on, raw materials became the main driver of German China policy.

In 1933, Hans von Seeckt , who had come to Shanghai in May of that year, became the chief adviser for Chinese overseas economics and military development with regard to Germany. In June 1933 he published the memorandum for Marshal Chiang Kai-shek on his program for the industrialization and militarization of China. He called for a small, mobile, and well-equipped army instead of a large but under-trained army. For this purpose, a framework should be created in which the army is the pillar of the government, its effectiveness is based on qualitative superiority and this superiority is derived from the quality of the officer corps.

Von Seeckt suggested uniform training of the army under Chiang's command and the subordination of the entire military into a centralized network, similar to a pyramid, as the first steps in creating this framework. A “training unit” should be set up for this purpose, which should serve as a model for other units. So a professional and competent army with a strictly military officer corps should be formed, which is controlled by a central authority.

In addition, China would have to build up its own defense industry with German help, since it could not always rely on buying weapons abroad. The first step towards efficient industrialization was centralization - not only that of the Chinese reconstruction companies, but also that of German companies. In January 1934, the trading company for industrial products (Hapro for short) was founded in order to bundle Germany's industrial interests in China. Hapro was nominally a private company, through which the influence of other countries should be avoided. In August 1934 a contract was signed to exchange Chinese raw materials and agricultural products for German industrial products. Accordingly, the Chinese government should deliver strategically important raw materials in exchange for German industrial products and technologies. This barter transaction was extremely useful for Sino-German cooperation, because China had a very high budget deficit due to the high military spending in the time of the civil war and could therefore not take out loans from the international community. The contract also made it clear that Germany and China were equal partners and equally important for this exchange. After initiating this milestone in Sino-German cooperation, von Seeckt handed over his post to General Alexander von Falkenhausen and returned to Germany in March 1935, where he died in 1936.

Industrialization of China

In 1936, China had only about 16,000 km of railroad tracks, far less than the 150,000 km Sun Yat-sen allowed for his vision of modernized China. In addition, half of these routes were in Manchuria , which had already been lost to Japan and was therefore no longer under the control of the Kuomintang. The slow progress in modernizing the Chinese transportation system was based on the conflict of foreign interests in China. The interests of the four-power consortium of 1920, consisting of Great Britain, France, the USA and Japan, in banking are to be cited here as an example. This consortium aimed to regulate foreign investment in China. The agreement stipulated that one of the four states could only grant the Chinese government a loan if unanimous approval was given. In addition, other states were reluctant to provide funds because of the global economic crisis.

Nevertheless, the construction of the railroad in China was greatly accelerated by Sino-German agreements in 1934 and 1936. Important lines were built between Nanchang , Zhejiang and Guizhou . This development was also made possible by the fact that Germany needed an efficient transport system for the export of raw materials. In addition, these railroad lines helped the Chinese government build an industrial center south of the Yangtze River . After all, the railroad was used to perform military functions. For example, the Hangzhou - Guiyang line was built to support military transports in the Yangtze River Delta, even after Shanghai and Nanking were lost. Similarly, the Guangzhou - Hankou line was used for transportation between the east coast and the Wuhan area. The value of the railroad would become apparent at the beginning of the Second Sino-Japanese War .

The most important industrial project of the Sino-German cooperation was the three-year plan of 1936, which was implemented jointly by the Chinese government's national raw materials commission and Harpo (see above). The purpose of this plan was to build up Chinese industry for the time being so that China could withstand a Japanese attack, and in the long term to build a center for the future industrial development of China. Some of the fundamental elements of the plan were the monopoly of all tungsten and antimony- related factories, the establishment of central steel and machine plants in provinces such as Hubei , Hunan and Sichuan, and the development of power plants and other chemical plants. As fundamentally agreed in the 1934 exchange agreement, China would supply raw materials for Germany to provide the necessary expertise and equipment. An overflow in costs on the German side was alleviated by the fact that the price of tungsten more than doubled in the period from 1932 to 1936. The three-year plan created a class of highly educated technocrats who were trained to lead the state projects. While the plan made many promises, many of its accomplishments were ultimately undermined by the outbreak of war against Japan in 1937.

Armament of China

Alexander von Falkenhausen was largely responsible for the military training, which was also part of the trade. Hans von Seeckt's plans called for a drastic reduction in the military to 60 divisions well trained in accordance with German military doctrines, but the question of where savings should be made remained open. The entire officer corps that were trained in the Whampoa Military Academy until 1927 was qualitatively only slightly better than the leaders of the warlord armies, but remained of great value to Chiang Kai-shek because of its sheer loyalty. Nevertheless, around 80,000 soldiers in eight divisions were trained according to German standards. These represented the elite of the Chinese army. These new divisions may have contributed to Chiang's decision to escalate the fighting at the Marco Polo Bridge into war. However, China was not yet ready to oppose Japan. Hence, Chiang's decision to send all new divisions into the battle for Shanghai cost two-thirds of his best troops, which had been trained for years. He did this against all objections of his staff officers and against the advice of Falkenhausens, who suggested that he maintain his fighting strength in order to maintain order and to fight later.

Von Falkenhausen recommended that Chiang pursue attrition tactics against Japan, believing Japan could never win a long-term war. He suggested keeping the front on the Yellow River and only pushing north as the war progressed. Chiang should also be prepared to give up some northern regions of China, including Shandong . The retreat was supposed to be slow, however, so the Japanese could only advance with heavy losses. He also recommended the construction of fortifications near mining areas, the coast, rivers, etc. He also advised the Chinese to carry out guerrilla operations behind the Japanese lines. This should help to weaken the militarily more experienced Japanese.

Von Falkenhausen also took the view that it was too optimistic to expect that the Chinese army would have tanks and heavy artillery available in the war against Japan. Chinese industry was only just beginning to modernize, and it would be a while before the army was equipped in a manner similar to the Wehrmacht . Nonetheless, he emphasized the development of mobile forces based on the use of small arms and infiltration tactics .

However, German aid in the military field was not limited to training and reorganization. It also included military equipment. According to von Seeckt, around 80 percent of Chinese weapons emissions were below par or unsuitable for modern warfare. Therefore, projects were started to retrofit and expand existing factories along the Yangtze and to build new arms and ammunition factories. For example, the arms factory in Hanyang was rebuilt from 1935 to 1936 to meet standards. There should now Maxim machine guns , several 82mm grave mortar and Chiang Kai-shek rifle (中正式; Zhongzheng Shì), which on the German carbine 98k based, are made. Together with the Hanyang 88, this rifle formed the predominant weapon used by the Chinese army during the war. Another factory was built based on plans for a mustard gas production facility , the construction of which was demolished, to manufacture gas masks . In May 1938, additional factories were built in Hunan to produce 20mm, 37mm and 75mm artillery. A factory for the manufacture of optical equipment such as binoculars for riflescopes was built in Nanking in late 1936. Additional factories were built or expanded to manufacture other weapons or artillery, such as the MG-34 , mountain artillery of various calibres, and even spare parts for the Chinese army's light armored vehicles . Some research institutes were also set up under German protection. These included the “Bureau for Guns and Weapons” and the Chemical Research Institute under the supervision of IG Farben . Many of these institutes were headed by Chinese engineers returning from Germany. In 1935 and 1936, China ordered a total of 315,000 steel helmets and large numbers of Mauser rifles . China imported an additional small number of aircraft the company Junkers , Heinkel and Messerschmitt , some of which were only assembled in China, howitzers of Krupp and Rheinmetall , anti-tank guns and mountain guns like the PaK 37mm, as well as armored vehicles such as the Panzer I . These modernization measures proved their usefulness with the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War . Although the Japanese were finally able to capture the nationalist capital, Nanjing , it took several months and the costs far greater than either side had anticipated. Despite this loss, the fact that Chinese troops could credibly challenge the Japanese boosted Chinese morale immensely. Additionally, due to the high cost of the campaign, the Japanese were reluctant to advance further into China's interior, allowing the nationalist government to move the political and industrial infrastructure to Sichuan .

End of the Sino-German cooperation

The outbreak of the second Sino-Japanese War on July 7, 1937 destroyed a large part of the progress and the promises of almost 10 years of intensive Sino-German cooperation. Aside from the destruction of industrial plants, Adolf Hitler's foreign policy was the most detrimental to German-Chinese relations. In principle, Hitler chose the Empire of Japan as an ally against the Soviet Union because Japan had better military capacities for this purpose. This situation was made worse by the non-aggression pact between China and the Soviet Union of August 21, 1937, and despite violent protests from the Chinese lobby and German investors, Hitler could not be dissuaded from his position. Nevertheless, Harpo was allowed to deliver already placed Chinese orders, but no further orders from Nanking were accepted.

There were also plans for a German-mediated peace between Japan and China. However, with the fall of Nanking in December 1937, any compromise became unacceptable to the Chinese government. The German mediation plans were therefore abandoned. In early 1938, Germany recognized Manchukuo as an independent state. In April of this year Hermann Göring banned all deliveries of war material to China, and in May all German advisors were called back to Germany under pressure from Japan.

This change from a pro-Chinese policy to a pro-Japanese one also harmed German economic interests, because neither with Japan nor with Manchukuo was there as much trade as with China. A pro-Chinese stance was also evident among most Germans living in China. Germans in Hankou raised more donations for the Red Cross than all Chinese and other foreigners put together. Military advisors also wanted recognition for their contracts with the Chinese government. Von Falkenhausen was eventually forced to leave China by the end of June 1938. However, he promised Chiang that he would never disclose his work in China to help the Japanese. The German government proclaimed Japan a bulwark against communism in China.

Still, Germany's new relationship with Japan would prove sterile. Japan enjoyed a monopoly in northern China and Manchukuo, and many foreign companies were confiscated. The German interests were just as neglected as those of other nations. While negotiations to solve these economic problems continued towards mid-1939, Hitler concluded the German-Soviet non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union. This invalidated the German-Japanese Anti-Comintern Pact of 1936 and broke off negotiations. While the Soviet Union allowed Germany to use the Trans-Siberian Railroad for transports from Manchukuo to Germany, the volumes transported remained small and the lack of connections between Germany, the Soviet Union and Japan exacerbated the problem. With the German attack on the Soviet Union in 1941, Germany's economic activities in Asia ended.

Contact between Germany and China continued until 1941 and both sides wished to resume cooperation as the German-Japanese alliance was not very useful. However, towards the end of 1940 Germany signed the three-power pact with Japan and Italy. In July 1941, Hitler officially recognized the " Reorganized Government of the Republic of China " under Wang Jingwei in Nanking, which dashed all hopes of contact with the Chinese government under Chiang, which had been relocated to Chongqing . Wang's Nanking government also joined the Anti-Comintern Pact in 1941. After the attack on Pearl Harbor , Chiang's Chongqing-China formally joined the Allies instead and declared war on Germany on December 9, 1941.

Conclusion

The Sino-German cooperation of the 1930s was perhaps the most ambitious and most successful expression of Sun Yat-sen's ideal of an "international development" to modernize China. Germany's loss of territory in China after World War I, its need for raw materials, and its non-interference in Chinese politics increased the pace and productivity of cooperation with China. Because both countries could work together on the basis of equality and economic stability and without imperialist undertones, as with other foreign powers. China's urgent need for industrial development to combat a potential crisis with Japan also accelerated this process. Furthermore, the respect for the German resurgence after the defeat in World War I and Germany's fascist and militarist ideology spurred Chinese leaders to use fascism as a quick fix for China's ongoing disagreement and political confusion. In summary, although Sino-German cooperation, although short-lived and destroyed many of its results in the war against Japan for which China was only remotely prepared, had some lasting effects on China's modernization. After the Kuomintang was defeated in the Chinese Civil War , the nationalist government moved to Taiwan . Many government officials and officers of the Republic of China in Taiwan were trained as research personnel or officers in Germany, as was Chiang Wei-kuo , the son of Chiang Kai-shek. Part of Taiwan's rapid industrialization after the war can be traced back to the plans and goals of the 1936 Three-Year Plan.

literature

- Bernd Eberstein : Prussia and China. A story of difficult relationships. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-428-12654-5 .

- William C. Kirby: Germany and Republican China. Stanford University Press, Stanford CA 1984, ISBN 0-8047-1209-3 .

- Frederick F. Liu: A Military History of Modern China. 1924-1949. Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ 1956.

- Bernd Martin (Hrsg.): The German consultancy in China. 1927-1938. Military, economy, foreign policy. = The German Advisory Group in China. Military, Economic, and Political Sssues in Sino-German Relations, 1927–1938. Published in conjunction with the Military History Research Office. Droste, Düsseldorf 1981, ISBN 3-7700-0588-0 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Klaus Mühlhahn : Qingdao (Tsingtau) - A Center of German Culture in China? In: H.-M. Hinz, C. Lind (Ed.): Tsingtau - A Chapter of German Colonial History in China 1897–1914. DHM, Berlin 1998, ISBN 3-86102-100-5 , p. 130.