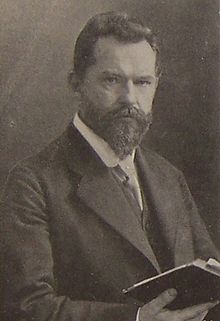

Eugen Kühnemann

Eugen Kühnemann (born July 28, 1868 in Hanover , † May 12, 1946 in Fischbach (today Karpniki) in the Giant Mountains (today Powiat Jeleniogórski , Poland )) was a German philosopher and literary scholar .

Life

Kühnemann was the son of the secret government councilor Eugen Kühnemann from Ratibor and the pharmacist's daughter Ida, née Stark, from Gnoien . In 1886 he began studying philosophy , classical philology and German studies in Marburg and heard lectures on Kant from Hermann Cohen . In 1887 he moved to Munich and heard the history of philosophy with Karl von Prantl , archeology with Heinrich Brunn and German literature with Michael Bernays . After an interim term in Berlin , he was at Bernays with a thesis on "The Kantian studies Schiller and the composition of Wallenstein" in July 1889 doctorate . Kühnemann then continued his studies in Göttingen with Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff in 1889/90 , for a semester in Paris with Hippolyte Taine and in Berlin in 1890 with Heinrich von Treitschke and Erich Schmidt . A first attempt to himself Wilhelm Dilthey to habilitieren failed 1894. Kühnemann moved to Marburg and became a lecturer in 1895 at Cohen with the habilitation thesis "Kant and Schiller reasons of aesthetics." In 1901 he was given an extra-ordinary extraordinary position in Marburg and in the summer semester of 1903 he was represented in Bonn against the will of the faculty there .

With the support of the amicably-minded university deputy in the Prussian Ministry of Education, Friedrich Althoff , Kühnemann went to the newly founded Royal Academy in Posen as founding rector in 1903 , a kind of higher adult education center. He saw his task in a "spiritual colonization" of the Poznan population:

“But the vast majority of the people were Polish. On this Polish people who had Prussia become a true benefactor. He had given Poland what it never had, an educated, efficient and honorable middle class. "

In addition to Kant's philosophy, Kühnemann's interests were primarily literature, especially the German classics. In 1905, on the occasion of the 100th on May 9, he wrote a book about Friedrich Schiller . On behalf of the Prussian Ministry of Culture he made in 1905 for the first time a lecture tour to America as a representative of the Association of German abroad , with the aim of Germans abroad , the "Empire German Spirit" (book title) closer match. Further stays abroad followed, including 1906/07 and 1908/09 as an exchange professor at Harvard University and in 1912 as the first Carl Schurz Memorial professor at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. Kühnemann received honorary doctorates from both universities . Kühnemann maintained contact with the USA with lecture tours from 1914 to 1917 and again in 1932 in the period that followed. In particular, the trips during the First World War served to influence the American public in favor of the Germans . During this time Kühnemann visited 137 cities in 36 countries and gave 121 speeches in English and 275 in German. He defended the German war policy including the sinking of the RMS Lusitania and the unrestricted submarine war .

When Kühnemann was not re-elected as rector in Posen in 1906, with the support of Althoff he was able to obtain an appointment to a full professorship in Breslau , where he held the Protestant proportional chair. There he was an outsider because of his strong literature-oriented thinking. Despite his time in Marburg and a two-volume book on Kant (1923-24), Kühnemann is not part of neo-Kantianism , but rather a nationalistic new idealism. His thinking revolved around the connection between spirit and life . Philosophy is to be interpreted from the human perspective. "This understanding grasps the whole of life and creation in the personality as a unity and measures it in its meaning for the spirit, which is itself a unity of eternal necessity ." He called Herder a "brilliant seer" and "prophet of Germanness and himself ." Glory ”Similarly, with his“ Speeches to the German Nation ” , he describes Fichte as a“ true prophet ”. He characterized the basic mood in Germany shortly before the First World War with the words: “We are beginning to understand that it is the cultural concept of Germanness that represents our duty in the world, and more than that - that it is used to decide our being and not being. ”For Kühnemann, a nationalist attitude and intervention in favor of one's own people was a philosophical duty:

“German philosophy is awareness of the German spirit and its importance for human work. It bears the ultimate responsibility for ensuring that the German spirit in its innermost striving for clarity. In the great moments of German history, German philosophy has always known that it has to intervene in the historical self-assertion and self-fulfillment of its people. "

After the USA entered the war, Kühnemann wrote a volume in the “Trench Books” series entitled “America as Germany's Enemy”, which had a circulation of 120,000. After the end of the war he hastened to comment in favor of the plans of American President Woodrow Wilson and, with reference to Kant, to welcome the idea of the League of Nations .

Paul Tillich and Karl Oscar Bertling received their doctorates at Kühnemann in 1910 and Siegfried Marck , a student of Hönigswald in 1911 , who also completed his habilitation with him in 1917. Another student at this time was Schlomo Friedrich Rülf . Helmut Kuhn also received his doctorate from him in 1923. In Breslau Kühnemann maintained contact with the Gadamer family. Hans-Georg Gadamer's father was Professor of Pharmaceutical and Forensic Chemistry in Breslau. Gadamer said of Kühnemann: “Eugen Kühnemann was the first one I started studying with, because he was my parents' house friend. He was a very amusing man, but incomparably much more superficial than Hönigswald ”. Accordingly, Kühnemann's lectures were considered easier. “The others were satisfied with the great rhetoric of Kühnemann, who was a master speaker.” For example, Kühnemann gave the lecture “Explanation of Kant's Critique of Pure Reason as an Introduction to the Study of German Literature” in the 1918 summer semester, which was also documented by German studies students could be. A pupil described him: “Kühnemann was small and delicate, a man with a goatee and glowing eyes. He was an ardent person in general. Whenever he talked about Nietzsche's Zarathustra or Goethe's Faust , his temper quickly carried him away and he stood with clenched fists in front of his captivated listeners. ”Kühnemann's aim was to work beyond philosophy, which he saw as the“ fundamental science of German literary history ” on the culture and the spiritual way of life.

"Higher than the scientific recognition that always despite its necessity validity due remains standing moral recognition in his knowledge of the unconditioned, higher nor the Religious in the knowledge not only to an unconditional task, but an absolute Being or sway. Life at the end of his knowledge is religion . In the beautiful, however, the soul plays in the feeling of divine perfection and in appearance achieves what reality fails. "

In the 1920s, Kühnemann mainly dealt with his two great role models, Kant and Goethe, on each of which he developed a two-volume monograph. In addition, in 1927 he published Volume VI of the series “Philosophy in Self-Presentation” with an autobiographical chapter. He became a member of Alfred Rosenberg's Kampfbund for German culture . As a German national, Kühnemann was a supporter of Papen and hoped that, together with the NSDAP, “a people's state of national freedom of will” would emerge. When Hitler did not enter into a coalition with the conservatives after the Reichstag elections in November 1932 , he spoke of a failure as a “people's leader”. Kühnemann welcomed the takeover of power, but did not join the NSDAP. He was valued by Reich Minister of Education Rust . “Kühnemann was an opponent of the Weimar Republic. of party state, of democratization, which he considered to be a 'mindless imitation of American democracy'. On the other hand, he liked to act as a philosophical citizen of the world, for whom there seemed to be no petty national borders in intellectual matters, especially when it came to 'great minds'. So he named Spinoza and Goethe in the same breath and spoke of inspiration and spiritual affinities of both. ”He also found in 1932 that the bourgeoisie was“ bearer of state-conscious unity ”. After 1933, he found no positive response from students with such views. Accordingly, in 1935 the National Socialist Student Union ensured that Kühnemann's retirement was not allowed to hold any further lectures. He was released from teaching in the summer semester of 1936, although there was still no successor and his position had to be replaced. In the following years Kühnemann was still active with a series of lectures.

In 1941 he gave the opening speech for the newly founded Imperial University of Posen . In 1945 he retired to Fischbach in the Riesengebirge, where he kept in close contact with Gerhart Hauptmann , who lived in nearby Agnetendorf and died three weeks before him.

After the end of the Second World War, Kühnemann's writings, The Friends, the Mine and Me, on my seventieth birthday (July 28, 1938) (Salzer, Heilbronn 1938), Goethe's Faust and the Easter Thought - Friedrich Nietzsche in its significance for contemporary thinking. 2 speeches (Trewendt & Granier, Breslau 1938) and The Freedom Struggle of the Germans (Nationale Verlagsgesellschaft, Leipzig 1941) in the Soviet occupation zone put on the list of literature to be segregated.

Fonts

- Turgenev and Tolstoj , Berlin 1893

- Herder's personality in his worldview , 1893

- Herder's Life , Munich 1895 (3rd edition 1927 under the title Herder)

- Basic tenets of philosophy. Studies on pre-Socratics, Socrates and Plato , Berlin and Stuttgart 1899

- On the basics of the teaching of Spinoza , Halle aS 1902

- Schiller , Beck, Munich 1905 (7th edition 1927)

- From the world empire of the German spirit. Speeches and essays , Munich 1914 (2nd edition: From the world empire of the German spirit, 1927)

- Germany, America and the War , Chicago 1915

- Germany and America. Letters to a German-American friend , 1917 (4th edition 1925).

- Gerhart Hauptmann. From the life of the German spirit in the present . Five Speeches, 1922

- Kant , two volumes, Munich 1923–24 (Volume 1: The European Thought in Pre-Kantian Thinking; Volume 2: The Work of Kant and the European Thought)

- Goethe , 2 volumes, Leipzig 1930

- George Washington. Becoming and Growing the American Idea , 1932

- With an unprejudiced forehead. My book of life (memories) , Heilbronn 1937

- Goethe's Faust and the Easter Thought. Friedrich Nietzsche in its importance for contemporary thinking. Two speeches , Breslau 1938

- The Germans' struggle for freedom , Leipzig 1941

literature

- Friedbert Holz: Kühnemann, Eugen. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 13, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1982, ISBN 3-428-00194-X , pp. 205 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Alfred Mann (ed.): Festschrift for Eugen Kühnemann on July 28, 1928, Breslau 1928 (published by the Volkshochschule Breslau).

Web links

- Works by and about Eugen Kühnemann in the German Digital Library

- Kühnemann, Eugene . In: East German Biography (Kulturportal West-Ost)

References and comments

- ^ Eugen Kühnemann's cousin Herbert Kühnemann was President of the German Patent Office .

- ↑ Kühnemann, Eugen . In: Ostdeutsche Biographie (Kulturportal West-Ost).

- ^ Eugen Kühnemann: With an unprejudiced forehead. My book of life (memories). Heilbronn 1937, p. 130.

- ↑ Eugen Kühnemann: Germany, America and the war. Chicago 1915, p. 36.

- ↑ Roswitha Grassl: Breslauer Studienjahre : Hans-Georg Gadamer in conversation, writings of the research project on the life and work of Richard Hönigswald . Mannheim 1996.

- ^ Norbert Kapferer : The Nazification of Philosophy at the University of Breslau, 1933–1945. Lit, Münster 2001, p. 24.

- ↑ Eugen Kühnemann: Herder's personality in his Weltanschauung, 1893, quoted from: Werner Ziegenfuß: Philosophen-Lexikon. de Gruyter, Berlin 1949, Volume 1, p. 694.

- ↑ Eugen Kühnemann: Herder. In: University and Abroad, 13 (1935), p. 36.

- ↑ Eugen Kühnemann: Fichte - the educator for the German nation. In: From the world empire of the German spirit. Munich 1914, pp. 171-194, 176.

- ↑ Eugen Kühnemann: From the world empire of the German spirit. Munich 1914, Foreword VII.

- ↑ Eugen Kühnemann: Germany and America , 1917, pp. 22-23.

- ↑ Peter Hoeres: War of the Philosophers. The German and British philosophers in World War I. Schöningh, Paderborn 2004, p. 324.

- ↑ Roswitha Grassl: Breslauer Studienjahre : Hans-Georg Gadamer in conversation, writings of the research project on the life and work of Richard Hönigswald . Mannheim 1996.

- ^ Norbert Kapferer: The Nazification of Philosophy at the University of Breslau, 1933–1945. Lit, Münster 2001, p. 25.

- ^ Eugen Kühnemann: Kant, Volume II, Munich 1924, quoted from: Werner Ziegenfuß: Philosophen-Lexikon. de Gruyter, Berlin 1949, Volume 1, p. 695.

- ↑ Norbert Kapferer: The Nazification of Philosophy at the University of Breslau 1933-1945. LIT Verlag, 2002, ISBN 3-8258-5451-5 .

- ^ Christian Tilitzki: The German University Philosophy in the Weimar Republic and in the Third Reich. Akademie, Berlin 2002, p. 374.

- ^ Friedbert Holz: Kühnemann, Eugen. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 13, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1982, ISBN 3-428-00194-X , pp. 205 f. ( Digitized version ).

- ^ Norbert Kapferer: The Nazification of Philosophy at the University of Breslau, 1933–1945. Lit, Münster 2001, p. 26.

- ^ Christian Tilitzki : The German University Philosophy in the Weimar Republic and in the Third Reich. Akademie, Berlin 2002, p. 364.

- ↑ http://www.polunbi.de/bibliothek/1946-nslit-k.html

- ↑ http://www.polunbi.de/bibliothek/1947-nslit-k.html

- ↑ http://www.polunbi.de/bibliothek/1948-nslit-k.html

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Kühnemann, Eugene |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German philosopher |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 28, 1868 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Hanover , Province of Hanover , Kingdom of Prussia |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 12, 1946 |

| Place of death | Fischbach , Poland |