Correspondence chess

In correspondence chess , chess is played by sending the moves to the opponent by post or electronically. In contrast to other chess competitions, the use of aids (literature, advice from other players, computer programs, ...) is not prohibited.

The moves are exchanged by postcard , fax , e-mail , on a chess server or through other media. Correspondence chess games are sometimes referred to as correspondence games . A remote game can be played over weeks, months or years. Except for Rapid Correspondence Chess, where the reflection time is calculated in days. The previously common definition of correspondence chess based solely on the special transfer of moves due to the spatial separation of opponents and the time to think about it calculated in days is no longer sufficient today. This is due to the fact that forms of competition that were previously reserved for games on the board, such as blitz games on chess servers, can be played by spatially separated opponents, and in rapid correspondence chess the time to think about is not calculated in days.

Traditionally, the trains were sent by postcard or letter. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, people also corresponded by telegraph or radio. There was even the approach of playing through a switchboard. In the 19th century, long-distance games were popular primarily as competitions between clubs or cities, and radio competitions between the USA and the USSR enjoyed great attention during the Cold War . However, the majority of the games took place between individual players. During wars , correspondence chess games could be affected by strict censorship measures due to the code used for the notation, which could bring games to a standstill.

Correspondence chess has a special tradition in Germany. This is how the Deutsche Fernschachbund e. V. the world's largest national association.

There are and still existed their own magazines for correspondence chess, such as the correspondence chess post and, from 1966 to 1990 in the German Democratic Republic, the correspondence chess bulletin , which from 1975 was called correspondence chess of the GDR .

Historical

The oldest known long-distance game took place in 1804 between the cities of The Hague (Lieutenant Colonel Friedrich Wilhelm von Mauvillon ) and Breda (officer, name not known). More important, however, was the battle between London and Edinburgh , which began in 1824 and which Edinburgh won 3-2 in 1828. During this time, city fights were very popular, with local chess players consulting, occasionally supported by well-known chess masters.

The first game played by telegraph took place in April 1845 between Howard Staunton and Henry Thomas Buckle . It lasted eight hours and ended in a draw.

The term "correspondence chess" was first used by Andreas Duhm (1883–1975) in the Swiss chess newspaper .

Correspondence chess rules

time to think

With the exception of Rapid Correspondence Chess, the time to think about correspondence is measured in days. Depending on the association, you have 30 to 60 days to think about ten moves, with the delivery time at least in the case of postal tournaments. The main role in calculating the cooling off period was the date of the postmark . Due to the mail delivery times, which a few years ago could be several weeks to the Eastern Bloc or to South America and back, there was the possibility of very deep and thorough analyzes .

Due to the delivery times of the letters, international batches in particular could take a few years. This is how the finals of the 10th Correspondence Chess Olympiad began in 1987 and ended in 1995. It was strange that the bronze medal won in 1995 - long after reunification - the GDR team.

The longest known long-distance game lasted 16 years. It was a game between K. Brenzinger from Pforzheim and FE Brenzinger from New York, which was played between 1859 and 1875 and ended after 50 moves with a victory for Black. The 1971 Guinness Book of Records reports on a game that was played by two players from Scotland and Australia from 1926 using Christmas greeting cards and was still going on at the time of publication. The notation of this part is not known, however.

Today fax, e-mail, SMS or chess servers are available as means of transmission. This eliminates the transit time for letters, which significantly shortens the duration of a long-distance batch. On chess servers, the reflection time is now measured to the minute and the average game duration is no longer one year, but several months.

Train transmission

notation

In correspondence chess by postcard, the algebraic notation (see chess notation ) is mostly used: Only the two fields on which the piece stood and lands are named, whereby the lines are not designated with letters but numbers. The resulting four-digit number consists of the line of the starting field, the row of the starting field, the line of the target field and the row of the target field. Lines a to h are counted as 1 to 8. In the case of a pawn promotion, a fifth digit is added for the piece resulting from the promotion. The numerical value is the opposite of the figure's strength, i.e. 1 for the queen, 2 for the rook, 3 for the bishop and 4 for the knight. The move f7 – f8D would be 67681 in correspondence chess notation. Pieces, punch marks and other special characters are omitted. Only the move of the king is given for castling. The move e2 – e4, for example, would then be 5254, instead of Qd8 – a5 you would write 4815. White short castling would correspond to 5171, as would the long 5131. In correspondence chess by e-mail, the Portable Game Notation (PGN) is now common.

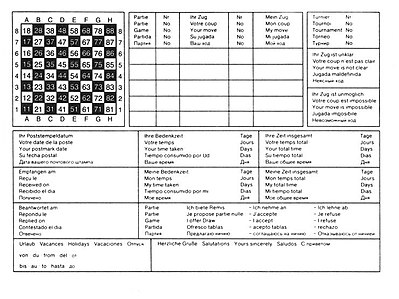

postcard

Traditionally, the trains were sent by postcard or letter.

Pre-printed postcards were often used. Here you entered the required data on a "form":

- last move of the opponent

- own reply train

- possibly contingent trains

- Postmark date of the opposing postcard

- Date of arrival of the opposing postcard

- Date of sending your own postcard

- The opponent's time to think about the last move and his total time to think about it

- Your own time to think about the current move as well as your own total time to think about it

- if necessary vacation notice (vacation from the party)

- possibly a draw offer, acceptance or rejection of the opposing draw offer, abandonment of the game

The moves were usually noted in the algebraic notation.

Since you often played against several opponents at the same time, the postage costs added up to a considerable amount. In order to save costs here, many German correspondence chess players took advantage of the cheaper “ Drucksache ” tariff of the Deutsche Post and Deutsche Bundespost (abolished in 1993) . For this purpose, no handwritten entries were permitted on the postcard other than the addresses of the recipient and the sender. Therefore, stamps were used with which the required data was stamped on the postcard.

Some German correspondence chess players tried to save costs by taking advantage of the free account management of some banks and savings banks. At national tournaments, they agreed to forego the postcard and instead to use the comments on bank transfer slips to send the moves; small amounts of money were transferred back and forth. This actually saved costs, but the bank transit times were usually longer than the postal transit times, which means that the batches were extended.

You can also reduce costs and the duration of the game by suggesting contingency moves to your opponent . In particular, if the opponent has only one permitted or reasonable answer move, one can write in a similar manner : I now move Bb5 +. If you answer Bd7, I'll play Qd2 on the next move . Longer contingency train sequences can also be suggested.

In the case of contingency suggestions, you should avoid using the phrase “any” or the like, in order to avoid unwanted effects. The following example is circulating as a bon mot: After 1. d4 g6 Black writes “2. Any, I play 2.… Bg7 ”. Then White moves 2. Bh6. Black now has to answer Bf8 – g7 as announced. White then wins the bishop with 3. Bxg7 and captures Black's rook on h8 on the next move.

Fax, e-mail, chess server, instant messenger

Since around 1990, postcard chess has been pushed into the background almost entirely by the media of fax, telephone, email, SMS and chess servers. Today the game by fax is hardly widespread either. The use of the Internet has not only increased in general, but has also increased above average among chess players of almost all age groups, which is why tournaments are often held on correspondence chess servers and e-mail tournaments at the correspondence chess associations. Instant messaging is also increasingly being used instead of e-mail .

The World Correspondence Chess Federation (ICCF) organized e-mail and fax tournaments for the first time in 1996.

National and international ratings

After a minimum number of games in tournaments, the players receive a rating as in tournament chess. The points achieved in a tournament and the opponents' scores are included in the rating. Nationally there is the correspondence chess rating number (FWZ) and internationally there is the correspondence chess rating number , whereby each association usually has its own rating system. The skill level can be determined according to the ratings. The averages of the scores of the opponents regulate according to category numbers how many points a player has to achieve in order, for example, to get a standard for the title “ International Master ”.

particularities

In correspondence chess, some rules of the game on the board are naturally overridden:

- The rule “ touched - guided ” does not apply. If an illegal move is transmitted, the piece that has been touched does not have to be moved.

- Assistance is allowed, e.g. B. joint analysis with others, use of chess literature, chess databases and also chess programs may be used. If a game is played by several players, it is called a circulation game .

Tournaments

National tournaments

The national tournaments are organized by the national correspondence chess federations. The German Fernschachbund e. V. (BdF) , formerly known as the "Bund Deutscher Fernschachfreunde", which was founded on August 25, 1946 in Frankfurt / Main, is the German national correspondence chess association. He is the German representation in international correspondence chess recognized by the International Correspondence Chess Federation ICCF. The German Correspondence Chess Federation offers promotion and relegation tournaments for individual players and teams, organizes the German championship and organizes other tournaments such as cup tournaments, general tournaments, themed tournaments and tournaments in Chess960 . These forms of tournaments enable chess players of all skill levels to find suitable playing partners. It organizes international matches and enables its members to play international correspondence chess.

The German Correspondence Chess Federation also offers "engine-free" tournaments in order to open up a range of games to members who refuse to use computers for move analysis. While all aids are normally permitted in correspondence chess, only the use of opening books or databases is permitted. Chess programs may neither be used for suggesting moves nor for checking planned moves.

When exchanging trains, players have the choice between server, e-mail, postcard and fax. In addition to the play area reserved for members, the German Correspondence Chess Federation maintains a free range of games and tournaments for everyone and chess players, regardless of membership. This so-called "BdF playground" offers tournaments that are played by e-mail.

In addition, the German Correspondence Chess Federation organizes an annual meeting for members and their relatives as well as for guests, the so-called correspondence chess meeting.

In addition, there are other correspondence chess clubs outside of the ICCF , which mainly have specialty offers.

International tournaments

ICCF

International tournaments are organized by the International Correspondence Chess Federation (ICCF). This was founded in 1928. The tournament structure here is similar to that of the national tournaments. Promotion and relegation tournaments take place. The ICCF also organizes the European and World Championships and the Correspondence Chess Olympiads.

IECG

As the second international correspondence chess association, the International Email Chess Group (IECG) established itself in the mid-1990s and has also been hosting world championships since 1996. It is limited to e-mail and servers and offers tournaments there for players of different levels and a cup tournament every year. All offers are free of charge.

Since e-mail seemed increasingly unsuitable as an exchange medium for trains, it was decided in October 2009 to stop the operation of the IECG and to move all its activities to the Lechenich SchachServer .

Correspondence chess and computers

Computers and chess programs have changed correspondence chess significantly in recent years. In addition to a sound understanding of chess, the ability to interpret and control computer analyzes is becoming increasingly important. The influence of computer analyzes on playing strength is controversial, but hardly any top player can afford to do without computer support completely. At least gross tactical errors have almost completely disappeared from tournament practice.

With the increased use of computers, correspondence chess has generally reached a tactical level within a few years that was previously reserved for the world's best.

On the other hand, this has also led to the fact that, due to the increase in the skill level of the chess programs, the enthusiasm of some chess players for correspondence chess has waned because they do not want to play against machines that the opponent may use as an aid.

The ICCF World Championships

Emergence

For the first time the idea of a correspondence chess world championship was presented in 1936 at a conference of the then World Correspondence Chess Federation IFSB (today ICCF). Prominent advocates were found, including a. in Alexander Rueb , the President of FIDE , the world champion Alekhine , in Keres and in Euwe . On August 10th, the IFSB decided in Stockholm to hold regular world championships. This could only be carried out by the successor organization ICCF after the Second World War . The first World Cup began in 1947. 78 players from 22 countries started in 11 support groups. In 1953, the Australian Cecil Purdy was the first world chess champion.

qualification

In order to participate in the final round of a world championship, you usually have to qualify. First you have to win a tournament of the ICCF master class with 15 participants, alternatively two wins in the ICCF master class with 7 participants or two second places in a group of 15 are sufficient. This allows you to participate in the semi-finals of a World Cup. Here you need place 1 or place 2 to be able to play in the 3/4 final. With 1st to 3rd place (which is determined by the ICCF) you reach the World Cup finals. The three-quarter final was introduced in 1974 at the ICCF meeting in Nice. Before that, you could qualify for the final directly from the semifinals. At the time of the postcard, the path to becoming a world champion could well take 15 years, mainly due to long international mail delivery times.

However, the ICCF can also award free places to chess players who have otherwise shown outstanding achievements, such as grandmasters . Such a side entry was granted , for example, to Fritz Baumbach at the 9th World Cup.

The 3rd World Championship is an exception. There was no preliminary round here. The first four of the 1st FW-WM, the first six of the 2nd FS-WM as well as those who played in the two previous finals were eligible to participate.

execution

The first world championships were held one after the other. The world champion and the runner-up were automatically qualified for the next finals. Because of the long mail delivery times, a final often lasted five years. In order to shorten the gaps, the finals were staggered from the 8th World Cup: even if the previous final was still running, the next World Cup final was started. The first two winners were then qualified for the World Cup after that.

For several years now, the world championships have been started alternately as traditional mail and e-mail tournaments.

The ICCF correspondence chess world champions

Fritz Baumbach lists in his book Who is the Champion of the Champions? the world champions, namely with the period of their world championships and the cross tables of the 1st to 21st world championships.

| No. | time | World Champion (ICCF) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1953-1958 | Cecil Purdy (AUS) |

| 2 | 1958–1962 | Vyacheslav Ragosin (USSR) |

| 3 | 1962-1965 | Alberic O'Kelly de Galway (BEL) |

| 4th | 1965-1967 | Vladimir Sagorovsky (USSR) |

| 5 | 1967-1971 | Hans Berliner (USA) |

| 6th | 1971-1975 | Horst Rittner (GDR) |

| 7th | 1975-1980 | Jakow Estrin (USSR) |

| 8th | 1980-1982 | Jørn Sloth (DEN) |

| 9 | 1982-1984 | Tõnu Õim (USSR) |

| 10 | 1984-1988 | Victor Palciauskas (USA) |

| 11 | 1988-1990 | Fritz Baumbach (GDR) |

| 12 | 1990-1994 | Grigory Sanakoyev (RUS) |

| 13 | 1994-1999 | Michail Umansky (RUS) |

| 14th | 1999-2001 | Tõnu Õim (EST) |

| 15th | 2001-2004 | Gert Jan Timmerman (NED) |

| 16 | 2004-2005 | Tunç Hamarat (AUT) |

| 17th | 2006 | Ivar Bern (NOR) |

| 18th | 2005 | Joop van Oosterom (NED) |

| 19th | 2006 | Christophe Léotard (FRA) |

| 20th | 2008 | Pertti Lehikoinen (FIN) |

| 21st | 2007 | Joop van Oosterom (NED) |

| 22nd | 2010 | Alexander Dronow (RUS) |

| 23 | 2010 | Ulrich Stephan (GER) |

| 24 | 2012 | Marjan Šemrl (SLO) |

| 25th | 2012 | Fabio Finocchiaro (ITA) |

| 26th | 2012 | Ron Langeveld (NED) |

| 27 | 2014 | Alexander Dronow (RUS) |

| 28 | 2015 | Leonardo Ljubičić (CRO) |

| 29 | 2018 | Alexander Dronow (RUS) |

| 30th | 2019 | Andrey Kochemasov (RUS) |

The ICCF correspondence chess world champions

The women's world championship began in 1965 with the preliminary rounds for the 1st World Cup.

| No. | year | World Champions (ICCF) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1972-1977 | Olga Rubzowa (USSR) |

| 2 | 1977-1984 | Lora Jakowlewa (USSR) |

| 3 | 1984-1992 | Luba Kristol (ISR) |

| 4th | 1992-1998 | Lyudmila Belavenez (RUS) |

| 5 | 1998-2005 | Luba Kristol (ISR) |

| 6th | 2005-2006 | Alessandra Riegler (ITA) |

| 7th | 2006-2010 | Olga Sukhareva (RUS) |

| 8th | 2010-2014 | Olga Sukhareva (RUS) |

| 9 | 2014-2017 | Irina Perevertkina (RUS) |

| 10 | 2017– .... | Irina Perevertkina (RUS) |

The ICCF world cup tournaments

| No. | year | Cup champions |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1973-1977 | Karl-Heinz Maeder (GDR) |

| 2 | 1977-1983 | Gennadi Nesis (USSR) |

| 3 | 1981-1986 | Nikolai Rabinovich (USSR) |

| 4th | 1984-1989 | Albert Popov (USSR) |

| 5A | 1987-1994 | Alexandr Frolov (UKR) |

| 5B | 1987-1994 | Gert Timmerman (NED) |

| 6th | 1994-1999 | Olita Rause (LAT) |

| 7th | 1994-2001 | Alexei Lepikhov (UKR) |

| 8th | 1998-2002 | Horst Staudler (GER) |

| 9 | 1998-2001 | Edgar Prang (GER) |

| 10 | 2001-2005 | Frank Schröder (GER) |

| 11 | 2008-2011 | Reinhardt Moll (GER) |

| 12E | 2005-2007 | Reinhardt Moll (GER) |

| 12P | 2009–2012 | Matthias Gleichmann (GER) |

| 13 | 2009–2012 | Reinhardt Moll (GER) |

| 14th | 2009–2012 | Reinhardt Moll (GER) |

| 15th | 2012-2015 | Klemen Sivic (SLO) |

| 16 | 2013-2016 | Uwe Nogga (GER) |

| 17th | 2014-2017 | Matthias Gleichmann (GER) |

| 18th | 2015-2019 | Reinhard Moll (GER) and Stefan Ulbig (GER) |

| 19th | 2014-2016 | Thomas Herfurth (GER) |

The IECG distance chess world champions

The first world championship of the International Email Chess Group was an invitation tournament. Then the players had to qualify. The year corresponds to the year of the start date. Since the championships began about 15 months apart, there are years without a start date, for example in 2001 when an invitation tournament was held again.

| year | World Champion (IECG) |

|---|---|

| 1996 | Simon Webb (ENG) |

| 1997 | Martin Pecha (AUT) |

| 1998 | Juan Sebastián Morgado (ARG) |

| 1999 | Wilfried Braakhuis (HOL) |

| 2000 | Albrecht Fester (GER) |

| 2001 | István Sinka (HUN) |

| 2002 | Jorge Rodriguez (ARG) |

| 2003 | Anatoli Sirota (AUS) |

| 2004 | Andreas Strangmüller (GER) |

| 2005 | Miguel Angel Canovas (ESP) |

| 2006 | Nigel Robson (ENG) |

After 2006 no more world championships were held. On December 31, 2010, the activities of the IECG were finally discontinued.

European championships

The European Championships are organized by the ICCF .

European champion in individual:

- Werner Stern (GDR, 1963–65)

- Jindrich Zapletal (CSR, 1964–67)

- Erich Thiele (GDR, 1965–68)

- Franček Brglez (YUG, 1966–70)

- Folke Ekström (SVE, 1967–72)

- Michail Gowbinder (URS, 1968–72)

- Werner Stern (GDR, 1970-74)

- Jørn Sloth (DEN, 1971-75)

- Aurel Anton (ROM) / Alexander Vaisman (URS) (1971-75)

- Ove Ekebjærg (DEN, 1972-77)

- Bela Toth (ITA, 1973-78)

- Klaus Engel (GER)

- Henrik Sørensen (DEN)

- Wilfried Sauermann (GER) / Anicetas Uogelė (URS)

- Hans Palm (GER)

- Hans-Ulrich Grünberg (GDR)

- Arkady Podolsky (URS)

- Vladimir Kalushin (URS, 1978–81)

- Arne Sørensen (DEN, 19 ?? - 83)

- Bent Sørensen (DEN)

- Sven Pedersen (DEN, 1980–86)

- Petr Yashelin (URS, 1980-86)

- Aleksandr Korelov (RUS, 1981–86)

- Alfred Deuel (URS, 1981-87)

- Vladas Gefenas (LTU, 1982-88)

- Gediminas Rastenis (LTU, 1983-89)

- Anatoly Sychev (RUS, 1983-90)

- Jānis Vitomskis (LAT, 1984–90)

- Frank Hovde (NOR, 1984-90)

- Anatoly Parnas (URS, 1985-92)

- Dieter Mohrlok (GER, 1985-92)

- Vladimir Usachy (UKR, 1985–93)

- Norbert Stull (LUX, 1986–94)

- Valentinas Normantas (LTU, 1987-94)

- Sergey Stolyar (RUS, 1987–94)

- Ričardas Žitkus (LTU, 1987–93)

- Libor Daněk (CZE, 1988-94)

- Gerhard Binder (GER, 1988-95)

- Günter Schuh (GER, 1988-94)

- Bo Hjort (SVE, 1989-94)

- Richard Polaczek (BEL, 1989-96)

- Wolfgang Häßler (GER, 1990-95)

- Vitaly Antonov (RUS, 1990-97)

- Walter Mooij (NED, 1991–97)

- Karl-Heinz Kraft (GER, 1991–95)

- Aleksey Lepikhov (UKR, 1992–97)

- Alfio Scuderi (ITA, 1992-97)

- Giampiero David (ITA, 1993-99)

- Ugo Fremiotti (ITA, 1993–97)

- Alius Mikėnas (LTU, 1994-98)

- Arne Vinje (NOR, 1994–98)

- Manfred Hafner (GER, 1994–98)

- Fatih Atakişi (TUR, 1994–00)

- Jörg Sawatzki (GER) / Michael Stettler (GER) (1995-99)

- Wieslaw Paśko (POL, 1995-99)

- Werner Hase (GER, 1995–99)

- Gabriel Cardelli (ITA, 1996–00)

- Siegfried Neuschmied (AUT, 1996–00)

- Vladimir Salceanu (ROM, 1996-02)

- Patrick Spitz (FRA, 1997-99)

- Paata Gaprindashvili (GEO, 1997–01)

- Ettore D'Adamo (ITA, 1997-01)

- Klaus Weber (GER, 2005-08)

- Andrej Loc (SLO, 2005-08)

- Christophe Pauwels (BEL, 2008-09)

- Carlos Cruzado Dueñas (ESP, 2008-09)

- Carlos Cruzado Dueñas (ESP, 2011–13)

- Daði Örn Jónsson (ISL, 2013–15)

- Costantino Delizia (ITA, 2015–19)

- Gerd Schowalter (GER, 2017-19)

- Alexandr Batrakov (RUS) / Igor Telepnev (RUS) (2017-19)

European Championships (teams)

The first European correspondence chess team championship took place from 1973 to 1983.

| No. | year | gold |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1978-1984 | Soviet Union |

| 2 | 1984-1988 | Soviet Union |

| 3 | 1988-1994 | Germany West |

| 4th | 1994-1998 | Germany |

| 5 | 1999-2004 | Germany |

| 6th | 2004-2009 | Germany |

| 7th | 2008–2012 | Slovakia |

| 8th | 2012-2014 | Sweden |

| 9 | 2014-2017 | Russia |

See also

literature

- Ludwig Steinkohl: Fascination with correspondence chess . Schachverlag Mädler, Düsseldorf 1984. ISBN 3-7919-0222-9 .

- Tim Harding (ed.): Games of world correspondence chess championships I-X . Batsford, London 1987. ISBN 0-7134-5384-2 .

- Fritz Baumbach: Correspondence Chess. 52–54 - stop, tips and tricks from the world champion . Sportverlag, Berlin 1991. ISBN 3-328-00398-3 .

- LCM Diepstraten: Tweehonderdvijftig jaar correspondentieschaak in Nederland. Historical notities bij een jubileum . Van Spijk, Venlo 1991. ISBN 90-6216-076-X .

- Alex Dunne: The complete guide to correspondence chess . Thinker's Press, Davenport 1991. ISBN 0-938650-52-1 .

- Bryce D. Avery: Correspondence chess in America . McFarland, Jefferson 2000. ISBN 0-7864-0733-6 .

- Sergey Grodzensky and Tim Harding: Red letters. The Correspondence Chess Championships of the Soviet Union . Chess Mail, Dublin 2003. ISBN 0-9538536-5-9 .

- Fritz Baumbach / Volker-M. Anton: Gladiators ante Portas . Self-published, http://www.anton-baumbach.de/ .

- Correspondence chess and computers

- Alex Dunne: Computers and Correspondence Chess . In: Chess Today , January 2, 2004. Link to the article (PDF; 151 kB)

Web links

- World Correspondence Chess Federation (ICCF)

- International Email Chess Group (IECG)

- German Correspondence Chess Federation (BdF)

- Swiss correspondence chess association

- Historical overview of correspondence chess

- InterFace Instant Messenger with integrated correspondence chess social network for chess clubs

- Jan van Reek: Highlights in the history of correspondence chess (English)

- The correspondence chess master as a chess researcher (Interview with the FS Grandmaster Arno Nickel / Glarean Magazin 2010)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Klaus Schmeh: Messages with a double bottom. In: Telepolis. March 1, 2009, accessed April 20, 2019 .

- ↑ Lechenich chess server

- ^ Fritz Baumbach, Robin Smith, Rolf Knobel: Who is the Champion of the Champions? - Correspondence Chess - . Excelsior Verlag GmbH, Berlin 2008, p. 202 (List of the world champions), ISBN 978-3-935800-04-4 .

- ↑ ICCF - World Championship 1 Final (English)

- ↑ ICCF - World Championship 2 Final (English)

- ↑ ICCF - World Championship 3 Final (English)

- ↑ ICCF - World Championship 4 Final (English)

- ↑ ICCF - World Championship 5 Final (English)

- ↑ ICCF - World Championship 6 Final (English)

- ↑ ICCF - World Championship 7 Final (English)

- ↑ ICCF - World Championship 8 Final (English)

- ↑ ICCF - World Championship 9 Final (English)

- ↑ ICCF - World Championship 10 Final (English)

- ↑ ICCF - World Championship 11 Final (English)

- ↑ ICCF - World Championship 12 Final (English)

- ↑ ICCF - World Championship 13 Final (English)

- ↑ ICCF - World Championship 14 Final (English)

- ↑ ICCF - World Championship 15 Final (English)

- ↑ ICCF - World Championship 16 Final (English)

- ↑ ICCF - World Championship 17 Final (English)

- ↑ ICCF - World Championship 18 Final (English)

- ↑ ICCF - World Championship 19 Final (English)

- ↑ ICCF - World Championship 20 Final (English)

- ↑ ICCF - World Championship 21 Final (English)

- ↑ ICCF - World Championship 22 Final (English)

- ↑ ICCF - World Championship 23 Final (English)

- ↑ ICCF - World Championship 24 Final (English)

- ↑ ICCF - World Championship 25 Final (English)

- ↑ ICCF - World Championship 26 Final (English)

- ↑ ICCF - World Championship 27 Final (English)

- ↑ ICCF - World Championship 28 Final (English)

- ↑ ICCF - World Championship 29 Final (English)

- ↑ - World Championship 30 Final (English)

- ↑ 1st Correspondence Chess World Championship for women Cross table and illustration of the participants

- ↑ ICCF - Ladies World Championship 1 Final (English)

- ↑ ICCF - Ladies World Championship 2 Final (English)

- ↑ ICCF - Ladies World Championship 3 Final (English)

- ↑ ICCF - Ladies World Championship 4 Final (English)

- ↑ ICCF - Ladies World Championship 5 Final (English)

- ↑ ICCF - Ladies World Championship 6 Final (English)

- ↑ ICCF - Ladies World Championship 7 Final (English)

- ↑ ICCF - Ladies World Championship 8 Final (English)

- ↑ ICCF - Ladies World Championship 9 Final (English)

- ↑ ICCF - Ladies World Championship 10 Final (English)

- ↑ 1 cup tournament (ICCF)

- ↑ 2 Cup tournament (ICCF)

- ↑ 3 Cup tournament (ICCF)

- ↑ 4 Cup tournament (ICCF)

- ↑ 5A Cup tournament (ICCF)

- ↑ 5B Cup tournament (ICCF)

- ↑ 6 Cup tournament (ICCF)

- ↑ 7 Cup tournament (ICCF)

- ↑ 8 Cup tournament (ICCF)

- ↑ 9 Cup tournament (ICCF)

- ↑ 10 Cup tournament (ICCF)

- ↑ 11 Cup tournament (ICCF)

- ↑ 12E Cup tournament (ICCF)

- ↑ 12P Cup tournament (ICCF)

- ↑ 13 Cup tournament (ICCF)

- ↑ 14 Cup tournament (ICCF)

- ↑ 15 Cup tournament (ICCF)

- ↑ 16 Cup tournament (ICCF)

- ↑ 17 Cup tournament (ICCF)

- ↑ 18 Cup tournament (ICCF)

- ↑ 19 Cup tournament (ICCF)

- ↑ IECG homepage

- ↑ 69 EU-M

- ↑ 70 EU-M

- ↑ 71 EU-M

- ^ Hermann Heemsoth , Hans-Joachim Heitmann: 1st European Correspondence Chess Team Championship 1973 - 1983 . Ed .: The International Correspondence Chess Federation - ICCF. 1980, ISBN 90-6448-506-2 .

- ↑ 1st EU-MM final round

- ↑ 2nd EU-MM final round

- ↑ 3rd EU-MM final round

- ↑ 4th EU-MM final round

- ↑ 5th EU.MM final round

- ↑ 6.EU.MM final round

- ↑ 7th EU-MM final round

- ↑ 8th EU-MM final round

- ↑ 9th EU-MM finals