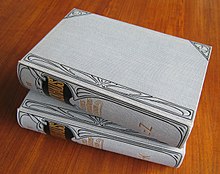

Book cover

The cover of a book or other printed matter is both the outer cover surrounding the block (in the case of a book: book block ) and the entire process of its manufacture. On the one hand, the result, i.e. the related unit of front and back cover (book cover) and the narrower spine (book spine), is described, on the other hand, the bookbinder's activity , which includes all steps from arranging and joining the layers to the artistic design includes. Historical, creative and technical aspects are scientifically examined by the binding research.

Forms of the book cover

Binding is difficult to systematize, as many names have arisen from old craft traditions and are therefore not subject to any consistent logic. Some types of binding are still reserved for individual production (hand binding), while on the other hand, industrial bookbinding has produced methods for publishing binding that cannot, or only to a limited extent, be transferred to the manual sector. Nevertheless, there are roughly two groups of labels:

Classification according to the cover fabric used

Four types of cover can be distinguished according to the type of cover fabric used . First, the cardboard tape , which can either mean a simple cover consisting of only one piece of folded cardboard , or a firm cover that is only covered with paper. Second, the fabric binding , which is covered with textile materials that can consist of both natural and synthetic fibers . Third, the leather binding , the oldest and most traditional form of binding, and fourth, the parchment binding , whereby a distinction must be made between the flexible copert and the solid, parchment-covered binding.

Leather, parchment and fabric volumes are still differentiated into full and half volumes , the designation depends on the cover material of the book spine. Since parchment cannot be processed by machine, it is only used in manual binding.

Classification according to the manufacturing technique

A fundamental distinction is to be made between the cover tape and the cover with attached book covers. While the first book block and cover are manufactured separately and only put together in a second step, with the "attached tape" the cover is produced directly on the book block. It can only be made by hand by the bookbinder or book restorer due to work processes that cannot be mastered with mechanical aids, which is why the cover tape was used in industrial book production and experienced its specific modern form.

The term brochure also refers, at least in its original French meaning, to the way it was produced, as does the English term softcover and its counterpart, the hardcover, which is common today .

Special forms and overlaps

Many other terms cannot simply be transferred to one of the two categories. A cover can therefore usually be assigned several terms from different areas. Some names, such as the jumping back book , refer not only to the manufacturing technique but also to their intended use. The Franzband also eludes a clear description. Since this is a special form of the attached leather strap, which differs in its manufacturing technique from conventional German leather straps, it cannot be clearly described either by its manufacture or by its reference material.

The Danish millimeter tape was developed in order to be able to produce a beautiful and attractive book cover with a leather spine with as little leather as possible during times of war.

Classification according to function

Further designations are possible for the function:

- Library cover for protective covers in libraries

- Use cover reduced to only the function of the book block casing-SETTING, formless covers

- Magnificent cover for particularly lavishly designed, representational covers

History of European cover design

Beginnings in antiquity

The development of the book cover ran parallel to the development of today's form of the book , the codex form. Simple books, consisting of a few layers of parchment, held together by cords in the fold and protected by a simple cover made of two wooden tablets, are documented for the first time in the first century AD . However, it was only later that the code began to prevail over its still widespread role . It was not until the 4th century AD that it became predominant and with it the protective role of the book cover.

The oldest surviving book covers come from Egypt . A cardboard box made of papyrus formed the basis here, wrapped in a cover made of goat or sheep leather. It was stapled on thin leather straps, which were passed through the fold of the still single-ply book blocks on the one hand, and through holes in the cover leather on the spine of the book on the other hand and were firmly knotted there. To close it, the upholstery fabric on the left side of the front cover was allowed to run out into a triangular flap, which could then be folded around the code like a flap.

Due to the limited scope of single-layer codices , multi -layer codices quickly began to gain acceptance, in which the layers were individually stapled, placed on top of one another and sewn together at the back. Only then did the connection with the binding take place, which could be done in a portfolio-like manner , by gluing the first and last sheet of the book block to the binding or by thread stitching .

The Copts' bindings have already been colored and decorated. Already in the late antiquity and the early Middle Ages here was used reactive printing , leather sectional , leather application , Lederflechtwerk, fretwork and hallmarking . In the Orient , these techniques have been applied, the West -oriented only at the beginning, between the 7th and 9th century Coptic models, later was limited here largely on leather sectional and stamp decoration.

The binding in the Middle Ages

At all times there were, in addition to simple practical covers, more splendid, richly decorated, splendid bindings made with great craftsmanship and precious materials. The Middle Ages, with its enormous importance of sacred literature, produced particularly outstanding examples in this regard and must therefore be viewed in a differentiated manner.

The splendid medieval binding

Magnificent church bindings were to be understood as a mirror of Christian dignity and power and were therefore decorated with the finest materials such as ivory , enamel , precious metals , precious stones and precious fabrics. The bookbinder himself usually only took on the technical part of the work with stapling the book block and fastening the book cover. The rest of the work was done by goldsmiths and enamellers, metalworkers and carvers or even painters.

For a large group of splendid medieval bindings, antique ivory tablets were torn out of their context and reused as adornment for liturgical books, regardless of their pictorial content . One of the oldest techniques of independent decoration, however, was goldsmith work. Wooden lids were partially covered entirely with sheet gold , Christian motifs were depicted in drifting work , and large quantities of precious stones and pearls were used , framed by precious metals .

Medieval splendid bindings can be divided into several large groups, which are based on the prevailing design element. The cross shape played a decisive role in many cases. But also the picture and frame type, in which a middle field, which mostly showed a Majestas Domini depiction, was in the center of consideration, belonged to the predominant motifs.

While the bindings from the Carolingian period were often still characterized by bulky decorations, in the 11th and 12th centuries there was a change to a more flat style of design. Engraved or perforated metal plates replaced the more plastic driving work. Often copper was used for this , which was subsequently gilded. The enamel technique of the pit smelting brought color life, as precious stones were used less and less. Wood carvings have also come down to us from this period.

The splendid bindings of the Gothic were more and more secular. Prayer and edification books continued to be lavishly decorated, but unlike before, they were not only intended for church use, but for private use. Above all, however, collections of laws, privileges or official account books were now adorned with more splendid bindings. Closely related to this was the development from the monastic to the civil bookbinder. In the design, more extensive jewelry techniques became popular again, driving work in silver and precious stones determined the equipment. Moved by the crusades , a large number of bindings were created depicting scenes of the crucifixion , and the depiction became more realistic. Increasingly, covers made of fine materials such as velvet , brocade or silk were used . The embossed plates were replaced by smaller decorative pieces and fittings that, in addition to the decoration, were supposed to protect the fabric from abrasion.

The medieval binding

The medieval binding usually consisted of leather-covered wooden covers. These could be left untreated or decorated with stencil lines and stamps using blind printing .

The Carolingian bindings of the 9th and 10th centuries were almost all bound in suede . In addition, some parchment envelopes are also occupied. In this case the stitching was carried out through the cover so that the threads were visible on the outside (long stitch stitching). A special feature of Carolingian bindings were the semicircular protruding flaps of the back cover. The jewelry was usually kept relatively simple. A surrounding frame was divided into geometric fields by further lines. Stamps, if any, were relatively small and, with simple bindings, were rather irregularly distributed over the surface of the cover . In the case of more sophisticated covers, they were arranged symmetrically , usually in a cross shape, on the front cover.

The bindings from the 12th and 13th centuries, also decorated with blind printing, are grouped together as the Romanesque bindings. The development started in France, from there, in the middle of the 12th century, spread to England and a little later also to the German-speaking cultural area. Brown cowhide or calf leather now became the preferred material, and red-dyed suede was used more rarely. The stamps' treasure trove of shapes increased to a great extent, and compositions that seem overloaded today shaped the design. The lid surface was almost always completely covered with stamps, there was no relation to the content. Ornamental stamps existed alongside plant-inspired motifs, depictions of animals and figurative stamps. Symbolic representations from the biblical area contrasted with secular motifs, which were often influenced by chivalry. In the German-speaking area, however, ornamental jewelry predominated.

The blind print volumes from the 14th and 15th centuries, and in some cases those from the first decades of the 16th century, are called Gothic bindings. The majority of the surviving specimens come from the German cultural area, but numerous examples can also be found in other European countries, first Italy and the Netherlands, then France and England and a few more. Work now passed more and more from the monastic to the bourgeois bookbinder, universities flourished, and a brisk book traffic developed in the trading cities. The design of the bindings varied considerably depending on their origin. Many Gothic bindings were only decorated with iron lines. Often, however, stamps were also added, and the lines then took over the structure of the top surface. The diagonal principle, a composition that divided the field into triangles or diamonds , was particularly popular . The diamond tendril pattern, which was formed by parallel wavy lines, also found a supra-regional distribution.

The emergence of embossing with plates or rolls represented a simplification in the production of much larger quantities, which brought about the invention of letterpress printing . Larger areas could be decorated in just one operation. In particular, the decoration with plant elements, the predominant motif of the Gothic, was easy to rationalize in this way. But the pressure with new stamp material rich in figures also increased.

The artistically high-quality leather cut volumes of the 15th century were a primarily German phenomenon . In the first half of the century they were rather flat and simple, in the second half then determined by the relief technique , they were considered luxury versions of the useful covers of this time. The most popular motifs were plant ornaments, often accompanied by inscriptions, but which were used as decorative elements. Animal scenes, coats of arms and figures of saints also played a larger role. Leather cutting was usually the work of freelance artists, the bookbinders only provided the basis.

Byzantine bindings from the Middle Ages differed from western bindings in particular in the way they were made. While in the West since about 600 n. Chr. On frets was stapled, who remained back smoothly here. The book block and cover also ended at the same height so that there were no protruding edges. For this reason, grooves were cut into the standing edges of the lid to make it easier to open. The wooden lids were mostly covered with goat or sheep leather. As in the West, blind printing was used as a rule, the types of composition and structure were varied.

Special forms of medieval bindings

In order to adequately protect valuable books or books that have been stressed by transport, some forms of special storage were developed in the Middle Ages. Book cases or book cases made of wood or metal were adapted to the shape of the book and served as protection on the journey. Like the contents, they too could be richly decorated. The so-called box books , in which the cover and side surfaces of the box were attached to the analogous parts of the cover and thus became a permanent part of the envelope, were a kind of connection between the book box and the binding .

Less valuable property was transported in leather book bags. Most of them were kept simple, only a few pieces with splendid leather driving or leather cutting work have survived. A real special form of the binding, however, was the so-called pouch books and sleeve bindings . While the cover material was left longer on the undercut in the former and could be tied to the belt in this way by knots, leather or fabric flaps hung over all the cuts in the case of the covers, in which the book could be wrapped.

The renaissance binding

Just like the entire artistic creation of the time, the cover ornamentation in the Renaissance was characterized by upheavals and innovations. Decisive influences for this came from the oriental region, but models from ancient iconography also played a role. The previously common wooden lids were slowly being replaced by cardboard lids , which made smaller formats possible, more colorful types of leather emerged, and gilding as lid decoration was equivalent to the previously predominant blind printing. In addition, numerous new styles developed from the adopted forms of jewelry, especially in France in the 16th century. Great bibliophile collectors also had a strong influence on the development of the decoration.

The Italian renaissance binding

Trade relations with the Orient opened the door to the rich experience of the Islamic world in cover decoration particularly early in the large Italian trading cities such as Venice or Florence. While gold printing had been known there since the 11th century, this jewelry technique only slowly came to Europe towards the end of the 14th century. The leather cut work was also based on Islamic models. In addition, antique elements were particularly popular. Knots and wickerwork, palmettes and especially plaques, images based on ancient coins or medals were the most common motifs. At the beginning of the 16th century, people began to increasingly adapt to the needs of humanistic teachings. Based on a series of small-format classic editions with cardboard covers, published by Aldus Manutius in Venice, the so-called Aldinen , a new form of practical cover was developed.

The French renaissance binding

The French art of binding in the Renaissance was strongly based on Italian models. Gold printing became particularly influential from the first decades of the 16th century, with stylized leaf shapes and ribbon work dominating the motifs . In addition to blank and full stamps, the so-called fers azurés , hatched stamps, whose lines were reminiscent of the depiction of the coat of arms color blue in heraldry , developed. Covers with these stamps can first be found in Lyon around 1530. Another special feature were the petits fers , especially small pistils that were combined to form larger leaf patterns.

One of the most important bibliophiles of this time was Jean Grolier , whose bookbinders had a decisive influence on the French cover design of the 16th century. But the French kings, especially in the second half of the century, showed a great sense of book art and its promotion. One style that appeared in this context was the Semé (or Semis) style (semis fr. , Aussat), a pattern that is characterized by the regular, constant repetition of individual small motifs on the entire surface of the lid, in contrast to the Scattering pattern with its irregular distribution of small elements.

In the second half of the 16th century and the beginning of the 17th century, however, the style of the splendid bindings was the fanfare style (à la fanfare). Contrary to the prevailing opinion, Nicolas Ève , the court bookbinder Heinrich III. , had been the inventor of this style, he was only a representative among numerous bookbinders who structured their bindings with symmetrically arranged tendrils and band works. However, the name Stil à la fanfare did not develop until the 19th century from the beginning of the title of a work that the bibliophile Charles Nodier commissioned to bind in the manner of this Renaissance decoration .

The renaissance binding in the German-speaking area

German bookbinders were initially very cautious about the new influences. Blind printing as the dominant form of jewelry and the heavy wooden lids lasted even into the 18th century - but here only for large volumes such as Bibles. The craftsmen, who were rooted in the guild rules, found it difficult to break away from the simple and time-saving techniques of scroll and plate decoration. In the first decades of the 16th century, iconographic elements of the Renaissance slowly began to penetrate German motif treasures. Figurative motifs such as biblical figures and themes, but also portraits and coats of arms now shaped the plate cuts. A reference to the content of the book was relatively rare. Slowly, gold and blind printing began to be used in parallel. From the middle of the 16th century, ornamental Renaissance motifs also established themselves in Germany. Southern cities in particular, such as Augsburg and Munich, were influenced by the Italian and French models.

The English renaissance binding

As in the German cultural area, the Italian-French Renaissance binding style did not establish itself until relatively late in England. From the 1640s at the latest, however, arabesques, ribbon work, semi-style and varied leaf shapes were also used here. English bookbinding flourished again under Elizabeth I in particular . The queen preferred textile bindings, so numerous velvet and silk ribbons were worked with elaborate embroidery. Another special feature were so-called twin volumes, bindings for several books that shared the spine or cover. Although they were particularly popular in England, some specimens are also known from the northern parts of Germany and Denmark.

The Spanish renaissance binding

The Spanish Renaissance binding is an exception in certain respects. The proximity to North Africa had led to a mixture of oriental and occidental influences early on. The Mudejar bindings from the 13th to 16th centuries therefore showed Islamic influences well before the other countries. One can only speak of a renaissance like in Italy or France to a limited extent. Nevertheless, influences from neighboring countries began to be adopted here in the 16th century.

The binding in baroque and rococo

17th and 18th century bindings were clearly dominated by French art. Own contributions came from England and Italy. The other European countries largely oriented themselves to the powerful models. Since the books in libraries were placed with their backs facing outwards, the ornamentation on the back and especially the title on the back became important. Extensively gilded stamp and roll motifs played a role in the decoration. In the 18th century, leather mosaics were also used in the production of luxury bindings.

The baroque and rococo binding in France

As in the Renaissance, the predominant position of French binding art can be explained by the great influence of bibliophilia, especially from aristocratic circles. The high demand for precious and richly decorated covers led to great creativity in design.

First of all, in 1620, the so-called Pointillé style developed from the fanfare style , which worked with the dissolution of lines in rows of dots and thus developed a very filigree effect. Two of the most famous bookbinders of the time, Le Gascon and Florimond Badier , are said to have invented and perfected this style. As a result, Pointillé elements were lavishly combined with other styles both in France itself and in neighboring countries. For this purpose, the stamps were mostly densely packed over the entire surface of the lid.

But there were also bindings with a restrained design. Binding à la François Bourgoing, for example, only adorned the edges of the top surfaces, leaving the center free. In this context, spiral stamps appeared, which were used alongside the Pointillé stamps in the 17th century. The style à la grotesque , on the other hand, represented a form of exclusive back ornamentation . One and the same stamp was repeated over and over again in narrow rows from head to toe. The bindings of the Cistercian convent Port-Royal-des-Champs were also a special form due to the rigor of their design . The style, called Jansenist bindings according to the belief of its residents , was characterized by lack of decoration, but excellent leather quality and execution of the binding, as well as high-quality title embossing.

The formative style of the 18th century was the lace style (à la dentelle) . This pattern mimicked textile lace and embroidery and was usually made in minute work using individual stamps. Occasionally a role was only used for the edges or more extensive designs. The Dentelles jewelry was mostly limited to the edges of the book covers, the extent to which the tip edge extended towards the middle, indicated the handwriting of individual artists. Antoine Michel Padeloup le jeune , son of a famous Parisian bookbinding family, is considered to be the inventor of the lace style. He also worked on numerous sophisticated leather mosaics. Other big names were those of the Derôme, Le Monnier families and the Parisian master Augustin Duseuil.

The binding of the Baroque and Rococo in the German-speaking area

The influences of the Renaissance continued to have an impact in Germany for a long time. If, on the other hand, you were influenced by newer styles, the bindings still did not achieve the quality of their models. Only the electoral court bookbindery in Heidelberg produced independent and high-quality designs. The Thirty Years' War paralyzed all cultural activity for a long time. One was forced to cut costs, sophisticated binding art was not in demand. Even afterwards, the prerequisites for the development of one's own styles were lacking; what the neighboring countries created was copied and received. In the 18th century, however, an independent group was represented by gilded and painted parchment bindings, some of which were decorated with blind printing.

The baroque and rococo binding in Italy

Italy, too, was influenced in large part from the outside, showed up in the processing, however creative and also created their own contributions, as in the first decades of the Baroque occurring compartments style (à l'éventail) . This style was based on long teardrop-shaped blank stamps that were combined into rosettes or rosette cutouts and filled with pointillé patterns. It spread throughout Europe, was popular in Germany and England, but especially in Italy it lasted well into the 18th century.

The baroque and rococo binding in England

In addition to France, the English bookbinding industry in Baroque and Rococo was particularly characterized by original style developments. Charles II's accession to the throne brought a bit of the French way of life to England and revived the local arts.

The so-called cottage (roof) style appeared as the first new form of decoration around 1660 . The eponymous roof gable shape was the decisive design feature of this style, which, like the indicated side walls, was represented linearly. The spaces in between were usually filled with all kinds of motif stamps such as plants, birds and vases. The all-over style, on the other hand, showed a symmetrical, but otherwise not influenced by any compositional principle, free arrangement of stamps over the entire surface of the lid. The Rectangular Style also worked with a rich stamp insert, but in contrast to the all-over style, the lid surface was divided into a wide frame and a central field. All of these three styles are particularly associated with the royal court bookbinder Samuel Mearne today . The cradle stamp was another invention of English binding at the time.

At the beginning of the 18th century, the Rectangular Style finally developed into the Harleian Style , named after the bibliophile Sir Robert Harley , who commissioned the decorated covers. The basic concept of frame and dense stamp decoration corresponds to that of the model, but the individual motifs were inspired more delicate and increasingly naturalistic. The most important English bookbinder of the 18th century was Roger Payne . Although rather reserved in its design, numerous well-known bibliophiles were among his customers. In part he was based on Mearne, but to a large extent he was already attached to the following classicist tendencies. He cut his stamps and his writings himself.

Classicism and Historicism in the late 18th and 19th centuries

As early as the end of the 18th century, the beginnings of an antiquing phase in cover design were evident in England. The Etruscan style was based on paintings of Etruscan vases, was then extended to the entire breadth of ancient motifs such as urns, cornucopia , lyre , sphinx, star patterns, sun vortices and laurel wreaths and was known as the Empire style . After a temporary cut caused by the French Revolution , at the beginning of the 19th century there was a tendency to limit the design to the edges of the lid. Classicist and naturalistically inspired borders as well as an emphasis on the back decoration were common. It was not until the second quarter of the century that the entire surface of the lid was decorated again. Blind printing was also revived and now appeared on the same cover with the same value alongside gold printing .

The 19th century had little to offer in terms of new styles. An eclectic mix and replication of historical styles dominated European bookbinding. In addition to the manual binding occurred around the middle of the century, machine-made publishing cover , which was not without influence on the type of design.

France's art of binding in the 19th century

Initially, at the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries, France was also influenced by the English Empire style, which was also called style anglais here . Motifs were found particularly in the Egyptian cultural area after Napoleon's campaign had greatly sparked interest in this region. Alexis-Pierre Bradel and the Bozérian brothers were among the great French bookbinders of the Napoleonic era .

The following romantic period was particularly characterized by the use of architectural elements in decoration. It was a phase of great enthusiasm for the Gothic creative period, which was reflected in the binding work in the cathedral style (à la cathédrale) . Large blind-pressed panels were often used here, which either replicated entire cathedral facades or were limited to characteristic structural elements and ornaments. The main master and inventor of the cathedral style was Joseph Thouvenin . It was also he who worked on the fanfare binding commissioned by Charles Nodier and thus coined the name of this style.

The reliures parlantes , the speaking bindings, represented a specialty of French cover creation . Unlike previously known, they tried to incorporate the book content into the cover design. Painted bindings, especially intended for almanacs or paperbacks for women, also appeared during this period.

From the 1830s began in France as in other countries in the course of industrialization the serial production of Verlagseinbänden one, first in factories , then in large binderies. The decoration was often determined by rational reasons. Large single-plate embossing, mainly as blind embossing on fabric, mostly on calico , was the standard equipment. This was only possible through the use of steam engines in “steam bookbinders”. In the course of the 19th century, there were more sophisticated and richly crafted bindings, some with detailed, multicolored images relating to the content of the text. Gold minting with gold surrogates also spread. After all, a magnificently designed publisher's cover was an important advertising medium when it was displayed in shop windows .

Classicism and Historicism in England

The already mentioned styles of the late 18th century, Etruscan and Empire Style, had their origins in England. Quite a few German bookbinders who had emigrated in the course of the Hanoverian-English personal union were involved in the developments there. During the Romantic period, the binding design developed parallel to that in France and the rest of Europe. Historizing motifs and representations determined the picture.

In the last quarter of the century, William Morris and Thomas Cobden-Sanderson initiated a movement for renewal in the arts and crafts that they wanted to contrast with the uniformity of industrial series production. The perfectly bound book should be the goal of their efforts. Sanderson's designs were particularly characterized by their penchant for natural forms.

Classicism and Historicism in Germany

The cover design in Germany at this time was mainly based on English but also French developments. The classicist binding was followed by the romantically inspired and historicizing binding. From the second half of the century, the publisher's binding played an increasingly important role. Its design was increasingly based on the content of the books. Bibliophilia, which could have been a motor for artistic creation, only played a subordinate role at the time. Goethe therefore expressed his preference for English bindings.

The cover work from the 20th century until today

In the first decades of the twentieth century, the book art movement led by Morris and Sanderson became the driving force behind European binding. The desire for the perfect binding turned into the desire for a unity of creativity in which all elements of the finished book should be related to one another. But Art Nouveau also brought decisive new impulses. For example, Paul Kersten in Berlin-Charlottenburg and his students at the Berlin Bookbinder College created special cover designs during the reform period . Born in Kirchheim unter Teck , Otto Dorfner , himself a student of Kersten, was connected to the Bauhaus between 1919 and 1922 through his workshop , then founded the independent Dorfner workshop and in 1926 took over a professorship with a chair at the State University of Crafts and Architecture in Weimar.

German bookbinders, who had still technically excellent hand bindings since the Middle Ages, but rarely produced independent design achievements, let themselves be influenced by the publisher's cover of all things at the beginning of the 20th century. Architects and painters have also been interested in the book since the turn of the century, took on its design and developed their own font styles . Otto Eckmann and Fritz Helmuth Ehmcke in particular mark the beginning of the interplay between graphics and binding that continues to this day . The teachings of the Bauhaus in Weimar were also of great importance for future designs.

There have been no more dominant styles since the middle of the 20th century. Rather, numerous individual currents existing side by side determine the picture. While the publisher's cover , usually wrapped in a bold dust jacket , usually captivates with its graphic solutions, hand bindings are still often based on historical models, but elements of New Objectivity or abstract art also have their place. In addition, the typographical design of the book title and the author's name play an unprecedented role today.

One area that is becoming increasingly important is the restoration of historical book covers. Up until the 1970s, it was common practice in many libraries to simply replace damaged covers, which meant that not only the cover itself was lost, but also sources for researching the history of the book in question (e.g. ownership entries). Today, however, attempts are being made to preserve the binding as a historical document, the aim being on the one hand to make the book usable, but on the other hand to impair the existing signs of age and the historical substance as little as possible so that the property as a historical record is preserved.

literature

The entire historical presentation of this article is based on the presentation of the standard work by Otto Mazal: Einbandkunde. Reichert, Wiesbaden 1997. All aspects can be found there in chronological order.

- Ernst Ammering: Book covers ( = The bibliophile paperbacks 475 ) . Harenberg , Dortmund 1985, ISBN 3-88379-475-9 .

- Gustav AE Bogeng : The book cover. A manual for bookbinders and book lovers ( = book studies. Collected by Bernhard Fabian and Ursula Fabian. Volume 5). 2nd unaltered reprint of the 3rd edition Halle 1951 . Olms, Hildesheim et al. 1991, ISBN 3-487-02552-3 .

- Ilse Valerie Cohnen: Book covers. A collection of outstanding examples . Schmidt, Mainz 1999, ISBN 3-87439-446-8 .

- Hellmuth Helwig: Handbook of the binding customer. 3 volumes. Maximilian Society, Hamburg.

- Volume 1 (1953): The development of cover decoration, its purpose, evaluation and literature. Preserving and cataloging. The cover hobby over the centuries.

- Volume 2 (1954): Bio-bibliography of bookbinders in Europe up to around 1850. Topo-bibliography of bookbinding. Directory of super libros.

- Volume 3 = register volume (1955): Name and place registers for the bio-bibliography of bookbinders Europe up to around 1850.

- Hellmuth Helwig: Introduction to Binding . Hiersemann, Stuttgart 1970, ISBN 3-7772-7008-3 .

- Thorvald Henningsen: The manual for the bookbinder . 2nd Edition. Hostettler et al., St. Gallen et al. 1969.

- Jean Loubier : The book cover in old and new times . H. Seemann, Berlin / Leipzig 1903 ( digitized version ).

- Hans Loubier: The book cover from its beginnings to the end of the 18th century. (= Monographs of Applied Arts 21/22) . 2nd revised and enlarged edition. Klinkhardt & Biermann, Leipzig 1926.

- Otto Mazal : Binding customer. The history of the book cover. ( = Elements of the book and library system 16 ) . Reichert, Wiesbaden 1997, ISBN 3-88226-888-3 .

- Armin Schlechter , Jürgen Seefeldt: Eye candy and protection. Bindings from the 15th to 17th centuries from the holdings of the Palatinate State Library in Speyer. ( = Publications of the State Library Center Rhineland-Palatinate 4 ) . State Library Center Rhineland-Palatinate, Koblenz 2008 (exhibition catalog).

- Max Weisweiler: The Islamic book cover of the Middle Ages: based on manuscripts from German, Dutch and Turkish libraries. (Contributions to books and libraries 10) . Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1962.

- Fritz Wiese: The book cover. A working customer with work drawings. 7th edition, reprint of the 6th supplemented. Schlueter, Hannover 2005, ISBN 3-87706-680-1 .

Web links

- The German bookbinding museum in the Gutenberg Museum Mainz

- Bindings of the Württemberg State Library in Stuttgart

- Association of Masters of Binding Art

- The digital binding collection in the University and City Library of Cologne

- Binding database ( EBDB ), Europe, 15th to 16th century

- Book cover. Crafts and arts. German Museum of Books and Writing , 2015, accessed on March 30, 2015 .

- Carsten Tergast: The cover - the book's calling card. ZVAB , accessed on May 11, 2015 .

- Binding collection of the Bavarian State Library

- Base des reliures numérisées de la Bibliothèque nationale de France. Retrieved May 28, 2018 (French).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Werner Williams-Krapp: book production. In: Medieval History. A digital introduction. Retrieved on January 21, 2017 (for bookbinding from 4:55 min).

- ↑ see also: Book cover from Maastricht (Louvre)

- ↑ Hans Loubier: The book cover. From its beginnings to the end of the 18th century. 2nd edition Klinkhardt & Biermann, Leipzig 1926.

- ↑ Paul Kersten, Ludwig Sütterlin: The exact book cover . Verlag von Wilhelm Knapp, Halle ad Saale 1909. (In the digital offer of the University Library Weimar. Goobipr2.uni-weimar.de )

- ↑ Example of a library's restoration guidelines (pp. 20–22 of the document) ( Memento from May 26, 2015 in the Internet Archive )