Brussels Capital Region

|

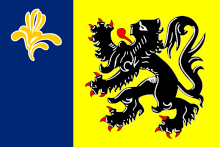

Brussels Capital Region Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest ( Dutch ) Région de Bruxelles-Capitale ( French ) |

||

|

||

| Member State of the Kingdom of Belgium | ||

|---|---|---|

| Type of state : | region | |

| Official language : | French , Dutch | |

| Administrative headquarters : | City of Brussels | |

| Foundation : | January 12, 1989 | |

| Area : | 161.36 km² | |

| Residents : | 1,208,542 (January 1, 2019) | |

| Population density : | 7362 inhabitants per km² | |

| Holiday: | 8th of May | |

| Prime Minister : | Rudi Vervoort ( PS ) | |

| ISO code : | BE-BRU | |

| Website: | be.brussels | |

| Location in Belgium | ||

The Brussels-Capital Region (or Brussels Region ), French Région de Bruxelles-Capitale , Dutch is one of the three regions of the Kingdom of Belgium and thus a member state of the Belgian federal state. It comprises the "bilingual Brussels-Capital area", which - like the administrative district of the same name - consists of 19 municipalities. The city of Brussels , also known as "Brussels City", is one of the 19 municipalities. The Brussels-Capital Region has existed in its current form since January 1, 1995. The region has 1,208,542 inhabitants (January 1, 2019).

The Brussels-Capital Region has a legislative body (“Brussels Parliament”) and an executive body (“Brussels Government”). The French and Flemish Community Commissions (“COCOF” and “VGC”) and the “Joint Community Commission” (COCOM / GGC) are also included. In addition, the Brussels-Capital Region also exercises the powers of the “Brussels agglomeration”.

This article mainly deals with the topics of politics, administration and the language situation. Additional and overarching topics are dealt with in the Brussels article .

Historical background

When the first state reform was decided in Belgium (1970) , which was supposed to lead to the federalization of the country, on the one hand the cultural communities (the later communities ), with the focus on culture , and on the other hand the regions , with the focus on the economy . Since the Flemish representatives did not recognize the purpose of these regions, their existence was recorded in an article of the constitution (107 quater ). No other specific implementation modalities were planned. In this Article 107 quater there was already talk of a “Brussels region”.

Even if the regions were not yet functional, a first common administrative structure was created for the nineteen Brussels municipalities: the Brussels agglomeration (see below ). A law of July 26, 1971 provided that the Brussels Agglomeration Council would be divided into two language groups. The first and only elections to the agglomeration council took place on November 21, 1971. The agglomeration had certain responsibilities in matters of spatial planning , transport , security, public health and cleanliness. A French and a Dutch culture commission were also set up, in which the members of the agglomeration council, depending on the language group, met and had certain powers in matters of culture and teaching. However, the law of July 26, 1971 was amended by a law of August 21, 1987 and many of the powers of the agglomeration were entrusted to the then already existing regions.

In Brussels these powers were entrusted to the "Regional Ministerial Committee". In 1974 three of these committees were created: one Flemish, one Walloon and one Brussels. Even if these committees only had an advisory function, they are still called forerunners of the regions. In Brussels, half of the committee was composed of senators and the other half of members of the agglomeration council.

The creation of the regions, including a Brussels region, was recorded in the two major Egmont (1978) and Stuyvenberg (1979) agreements. Due to a government crisis, however, these could not come into force, and so a law of July 5, 1979 created provisional community and regional institutions, the executive of which was provided solely by ministers of the national government.

It was not until the second state reform (1980) that the regions were really born. However, since no compromise could be found for the Brussels region, the adoption of the special law of 8 August 1980 alone marks the birth of the Flemish and Walloon regions . The “Brussels problem”, as it was called at the time, was “put in the fridge” (French: mise au frigo ).

Thus the 1979 law remained applicable to Brussels. A minister and two state secretaries, who were not responsible to the national parliament, directed the region's fortunes. This created serious financial and institutional problems. A compromise between Flemings and Walloons about the Brussels statute seemed to be a distant prospect, as the Flemish side in particular did not want to recognize Brussels as an independent region and the Walloon side did not want to accept absolute language equality.

Several legislative proposals were tabled, but it was not until May 1988 that a political compromise was found that satisfied all parties. This compromise led to the implementation of the third state reform and the passing of the special law of January 12, 1989, which is considered to be the birth of the “Brussels-Capital Region”, as it has been called since then. This special law finally brought the council (later parliament) and the executive (later government) into being and handed over the remaining competences of the agglomeration to the region.

In the fourth state reform (1993), which carried out the definitive transformation of Belgium into a federal state , and the previous "Saint Michaels Agreement" (Dutch Sint-Michielsakkoord , French accords de la Saint Michel ), the division of the province of Brabant was decided. The bilingual area of Brussels-Capital was "de-provincialized" (declared provincial-free), the provincial council and permanent deputation were abolished and, with a few exceptions (see below ), the powers of the province were transferred to the region.

The Lambermont Agreement and the fifth state reform (2001) did not result in any fundamental changes to the statute of the Brussels-Capital Region. Only the number of seats in the regional parliament was increased from 75 to 89.

Today the Brussels-Capital Region is politically established, but there is still no absolute agreement between Flemings and Walloons on the true statute of Brussels. The region still differs from the other two regions in that its legislative legal texts are called "ordinances" (and have a slightly different value than the regional "decrees"; see below ) and, unlike the other regions, it does not have the " constitutive autonomy ”, which allows the composition, election and functioning of parliaments and governments to be organized independently. The Brussels government has repeatedly called for new financing for the region in order to meet the challenges of a European and international center.

geography

The bilingual administrative district "Brussels-Capital" represents the territory of the Brussels-Capital Region. This area is congruent with the bilingual Brussels-Capital area within the meaning of Article 4 of the Constitution.

The 19 parishes

The Brussels-Capital administrative district consists of 19 municipalities, known as the "Brussels municipalities". The two official languages French and Dutch have equal rights in all 19 municipalities. The majority of the population is French-speaking. The municipality of Saint-Josse-ten-Noode / Sint-Joost-ten-Node is the most densely populated municipality in Belgium with around 24,000 inhabitants per square kilometer.

| local community | Residents January 1, 2019 |

Area in km² |

|---|---|---|

| Anderlecht | 119.714 | 17.74 |

| Auderghem / Oudergem | 34,013 | 9.03 |

| Berchem-Sainte-Agathe / Sint-Agatha-Berchem | 25.179 | 2.95 |

| Bruxelles / Brussel | 181,726 | 32.61 |

| Etterbeek | 48,367 | 3.15 |

| Evere | 41,763 | 5.02 |

| Forest / Vorst | 56,289 | 6.25 |

| Ganshoren | 24,902 | 2.46 |

| Ixelles / Elsene | 86,876 | 6.34 |

| Jette | 52,536 | 5.04 |

| Koekelberg | 21,990 | 1.17 |

| Molenbeek-Saint-Jean / Sint-Jans-Molenbeek | 97,462 | 5.89 |

| Saint-Gilles / Sint-Gillis | 50,267 | 2.52 |

| Saint-Josse-ten-Noode / Sint-Joost-ten-Node | 27,457 | 1.14 |

| Schaerbeek / Schaarbeek | 133,309 | 8.14 |

| Uccle / Ukkel | 83.024 | 22.91 |

| Watermael-Boitsfort / Watermaal-Bosvoorde | 25.184 | 12.93 |

| Woluwe-Saint-Lambert / Sint-Lambrechts-Woluwe | 56,660 | 7.22 |

| Woluwe-Saint-Pierre / Sint-Pieters-Woluwe | 41,824 | 8.85 |

| Brussels Capital Region (total) | 1,208,542 | 161.36 |

Proposal to merge the municipalities

The idea of a merger of these municipalities or their complete integration into the regional structure has often been suggested. While this merger would have obvious “ good governance ” benefits in the region, the proposal has never met with enough support from Francophone policymakers, who see it as a disruption of the institutional balance. The disproportionate representation (50F / 50N in government) of Dutch-speaking Brussels residents at regional level (see below ) may be a. compensated by reproducing the “true” balance of power (around 90F / 10N) at the municipal level.

Proposal to expand the region

In the course of the Belgian state reforms, the Francophone side repeatedly called for the expansion of the territory of the Brussels-Capital Region. Especially the FDF (Fédéralistes démocrates francophones) party , which sees itself as the defender of the francophone minority in the Brussels fringes, is calling for the " Facility Communities " (French communes à facilités , Dutch faciliteitengemeenten ) of the Brussels periphery , the Flemish province, to be joined -Brabant and are therefore part of the Flemish Region . These six so-called peripheral or Brussels peripheral communities , in which the Francophones actually make up the majority of the population, are: Kraainem (French Crainhem ), Drogenbos , Linkebeek , Sint-Genesius-Rode (French Rhode-Saint-Genèse ), Wemmel and Wezembeek -Oppem . In Flanders this demand is met with opposition from the public and from all Flemish parties. They see it as a destruction of Flemish territory and an attempt to further “Frenchize” (Dutch verdransing ) Brussels.

This conflict was last raised after the federal elections in 2007, when the split in the Brussels-Halle-Vilvoorde electoral district was negotiated. The enlargement of Brussels was also on the agenda of the francophone parties during the negotiations on the next state reform after the regional and European elections of 2009, which ultimately led to the overthrow of the Leterme II federal government .

Responsibilities and institutions

A special feature within the Brussels-Capital Region is that the elected mandataries exercise both regional and community competences in the region, even if this happens de jure in two different institutions.

Regional responsibilities

The competences of the Brussels-Capital Region - like the competences of the Flemish and Walloon regions - are set out in Article 6 of the special law of 8 August 1980 on institutional reforms. According to this article, with certain reservations, the regions are responsible for:

- Spatial planning and urban development

- Environment and water

- rural renewal and nature conservation

- housing

- Agriculture and fishing

- Economy and foreign trade

- energy

- Supervision of subordinate authorities

- Graves and burials

- Employment and work

- public works and transportation

- scientific research within their area of competence

- international cooperation within their area of competence

This also includes the competencies that the region has taken over from the Brussels agglomeration and the former province of Brabant . The region also has the power to raise its own taxes . In contrast to the other regions, however, it does not have the “constitutive autonomy” that allows the composition, election and functioning of parliaments and governments to be organized.

The Brussels Parliament

The Parliament of the Brussels-Capital Region (also known as "Brussels Parliament"; formerly "Council of the Brussels-Capital Region") is composed of 89 regional members. The President of Parliament is Rachid Madrane ( PS ).

The Brussels government

| Prime Minister | Political party | Reign |

|---|---|---|

| Charles Picqué (I + II) | PS | June 12, 1989 - July 15, 1999 |

| Jacques Simonet (I) | PRL | July 15, 1999 - October 18, 2000 |

| François-Xavier de Donnea | PRL / MR | October 18, 2000 - June 6, 2003 |

| Daniel Ducarme | MR | June 6, 2003 - February 18, 2004 |

| Jacques Simonet (II) | MR | February 18, 2004 - July 19, 2004 |

| Charles Picqué (III + IV) | PS | July 19, 2004 - May 7, 2013 |

| Rudi Vervoort | PS | May 7, 2013 - today |

The government of the Brussels-Capital Region (also Brussels Government ; formerly Executive of the Brussels-Capital Region ) is elected for five years by the Parliament of the Brussels-Capital Region. This government consists of a prime minister (since May 2013 Rudi Vervoort ), four ministers and three state secretaries, who do not necessarily have to be elected regional representatives. The law stipulates that the Prime Minister remains “linguistically neutral” and that at least two ministers and one State Secretary belong to the “less numerous” (i.e. Dutch) language group.

The government can issue decrees and ordinances. These are subject to the control of the Council of State - the highest Belgian administrative court - which can declare them null and void because they are illegal.

See also: Government of Picqué IV

Common responsibilities

The Brussels-Capital Region itself does not have any of the powers reserved for the three language communities . In principle, both the Flemish and the French Communities exercise their competences in the bilingual area of Brussels-Capital . According to Articles 127 to 129 of the Constitution, these are primarily:

- the cultural affairs

- the education (with some exceptions)

- the "personal" matters ( including health care )

Due to the “bilingual” statute of Brussels, however, these powers are mostly not exercised in Brussels by the communities themselves, but passed on to so-called “community commissions”. Since the federal system of Belgium does not know or tolerate subnationalities, these community commissions are not responsible for “Flemish” or “French-speaking” citizens of Brussels (nobody is forced to publicly choose one of the two communities), but only for the institutions that support it or can be assigned to that community (e.g. a French-speaking school or a Flemish theater group). In addition, following the “de-provincialization” of Brussels, the Community Commissions took over the community competencies previously exercised by the Province of Brabant .

There are three different Community Commissions (French, Flemish and Common) which are very different from each other.

The French Community Commission

The Commission communautaire française ( COCOF for short ) represents the French community in the bilingual area of Brussels-Capital. In contrast to its Flemish counterpart, the VGC (see below), the COCOF is a hybrid institution. It is not only a purely executive body, but also a completely autonomous decree-maker in certain areas of responsibility. COCOF and VGC have therefore developed asymmetrically since their foundation .

The COCOF was originally, just like the VGC, a purely subordinate authority under the administrative supervision of the French Community. Today it still has to implement the decrees of the French Community in Brussels and can, still under the supervision of the French Community, exercise its community competences independently by issuing “ordinances”. On this point the COCOF and the provinces in the rest of the French Community are similar .

In contrast to the VGC, however, at the beginning of the nineties the COCOF was given a completely independent decreed competence in certain areas of responsibility by the French Community. At that time the French Community was demonstrably in financial distress. In the fourth state reform (1993), for example, Article 138 was inserted into the constitution, which provides that the French Community can delegate the exercise of certain of its competences in the French-speaking area to the Walloon region and in the bilingual area of Brussels-Capital to the COCOF. This step was carried out by means of two “special decrees”, which require a two-thirds majority in parliament, for the following competencies: sports infrastructures , tourism , social support, retraining , further education , school transport , care policy, family policy (except family planning ), social assistance , integration of immigrants and Parts of disability and senior citizens policy . In these areas the COCOF draws up its own decrees with “legal status”. In this respect it is remarkable that the COCOF has also taken over the "international competence" of the French Community and can sign its own international treaties.

The COCOF has a legislative body (Council or Conseil de la Commission communautaire française ; sometimes also Parlement francophone bruxellois ), which is composed of the members of the French language group of the Brussels Parliament (currently 72 members), and an executive body (Kollegium or Collège de la Commission communautaire française ; sometimes Gouvernement bruxellois francophone ), in which the French-speaking members of the Brussels government are represented (currently three ministers, the Prime Minister - who is French-speaking - included, and two state secretaries).

The Flemish Community Commission

The Vlaamse Gemeenschapscommissie ( VGC for short ) represents the Flemish Community in Brussels, but has far less autonomy than its French-speaking counterpart. Indeed, the VGC is seen by the Flemish side less as an independent body than a subordinate authority whose job is only to apply the Flemish decrees in Brussels. The Flemish Community Commission works as a purely decentralized authority in cultural, educational and personal matters (only “ordinances” are agreed and implemented); it is therefore under the administrative control of the Flemish Community.

Nevertheless, the VGC has a legislative body (Council or "Raad van de Vlaamse Gemeenschapscommissie"), which is composed of the members of the Dutch language group of the Brussels Parliament (currently 17 members), and an executive body (College or "College van de Vlaamse") Gemeenschapscommissie ”), in which the Dutch-speaking members of the Brussels government are represented (currently 2 ministers and a state secretary).

The composition of the Council of the VGC was to be changed in 2001 as a result of the "Lombard Agreement" by adding 5 seats to the 17 members of the Dutch language group in the Brussels Parliament, which were also to be distributed among people who belong to the Had submitted lists to the Brussels Parliament for election, but not according to the election result in the Brussels-Capital Region, but according to the election result in the Flemish Region . The stated reason for this was the political will to prevent a possible majority of the right-wing extremist Vlaams Belang (then Vlaams Blok), which is particularly strong in the Dutch language group of the Brussels Parliament, but proportionally less strongly represented in the Flemish Parliament. However, this project was declared unconstitutional by the Court of Arbitration (now the Constitutional Court ) and the old composition of the VGC Council was retained.

The joint community commission

The Commission communautaire commune ( COCOM for short ) or Gemeenschappelijke Gemeenschapscommissie ( GGC for short ) exercises joint community competencies in the bilingual area of Brussels-Capital, i. H. those competences which are of "common interest" and not exclusively for the institutions of the French or Flemish Community . It is also a hybrid institution.

Originally, the COCOM / GGC was only a subordinate authority that takes care of the community competences of "common interest" (French: matières bicommunautaires ). In order to do justice to this task, just like the COCOF and VGC, it can selectively lead its own policy by adopting “ordinances”. Their situation is therefore also comparable to that of the provinces in the rest of the country. In addition, since the division of the former province of Brabant , it has exercised the “common interest” in the bilingual Brussels-Capital area. Although the COCOM / GGC acts as a “subordinate” authority here, it is noteworthy that no other institution in the Belgian state structure can exercise administrative supervision over it - not even the federal state. The ordinances - which have no legal value - can, however , be declared null and void by the Council of State because they are illegal.

In addition, according to Article 135 of the Constitution, implemented by Article 69 of the Special Law of January 12, 1989, the COCOM / GGC is responsible for those personal matters for which, according to Article 128 of the Constitution, neither the French nor the Flemish Community in the field Brussels are responsible. These are personal matters (i.e. health and social affairs) that cannot be assigned to either the French or the Flemish Communities (French: matières bipersonnalisables ). This affects public institutions that cannot be assigned to a community (e.g. public social welfare centers (ÖSHZ) or public hospitals in the bilingual area of Brussels-Capital), or direct personal assistance. Only in these cases is the COCOM / GGC completely autonomous and approves - just like the region - “ordinances” that have legal value (see above). It also has "international competence" in these matters and can therefore conclude its own international contracts.

The COCOM / GGC has a legislative body (United Assembly or "Assemblée réunie de la Commission communautaire commune" or "Verenigde vergadering van de Gemeenschappelijke Gemeenschapscommissie"), which is composed of the French and Dutch-speaking members of the Brussels Parliament (89 members ), and an executive body (United College or "Collège réuni de la Commission communautaire commune" or "Verenigd College van de Gemeenschappelijke Gemeenschapscommissie"), in which the French and Dutch-speaking ministers of the Brussels government are represented (5 ministers, including the Prime Minister who, however, only has one consultative voice). The organs of the COCOM / GGC are therefore completely congruent with those of the region.

A special task is entrusted to the United College with Article 136, Paragraph 2 of the Constitution: It also functions “between the two communities as a conciliation and coordination body”.

particularities

Aside from the community commissions specific to the Brussels-Capital Region (see above ), there are also other institutional uniqueness in and around Brussels that cannot be found in any other part of the Belgian federal state.

The Brussels agglomeration

Even if the constitution speaks of several agglomerations , one was set up in Brussels alone. The cities of Liège , Charleroi , Antwerp and Ghent have never shown the will to found their own agglomeration, although a legal framework for them already exists. However, the constitution also provides specific modalities for the Brussels agglomeration, namely the determination of agglomeration powers through a special law and their exercise by the Brussels regional institutions (parliament and government), which do not act in their capacity as institutions of the region, but for these cases act as “local authority” (and accordingly do not adopt ordinances, but ordinary “ordinances” and “decrees”).

The area of the Brussels agglomeration corresponds to that of the Brussels-Capital Region, i. H. the nineteen parishes. The powers of the agglomeration are precisely listed and are limited to four areas:

- the waste disposal and processing

- the fire protection

- the urgent patient transport

- the commercial passenger transport

Since the regional institutions take over the powers of the agglomeration, there is no administrative supervision.

The governor

After the division of the former province of Brabant and its disappearance, the office of governor was retained for Brussels. Alternatively, its functions would have been entrusted to a regional body (i.e. probably the Prime Minister of the Brussels-Capital Region). The result would have been: Since the governor is a commissioner of the federal government, the federal government would have had a certain amount of supervision over the regional body through the governor. That was not in the interests of the state reform at the time.

The governor of the prefecture of Brussels is (d. H. By permission) from the Government of the Brussels-Capital Region according to the equivalent opinion of the Ministers of the Federal Government appointed. He exercises more or less the same powers as the other provincial governors, except that he does not hold the chairmanship of the permanent deputation (or provincial college), which has also not been the case in the Walloon Region since 2006, as there is such a permanent deputation no longer exist in the Brussels-Capital administrative district since the "de-provincialization". According to Article 5, § 1 of the Provincial Law of April 30, 1936, the governor exercises the powers provided for in Articles 124, 128 and 129 of the same law. These responsibilities mainly concern:

- the maintenance of public order

- the coordination of police and civil defense services

- the preparation of a contingency plan for the Brussels-Capital district and disaster management

- the special supervision of the Brussels police zones

- issuing travel visas

- the application of the legislation on the use of weapons

After the last state reform, which gave the regions full control of the local authorities, the New Municipal Law in the Brussels-Capital administrative district was changed so that the governor no longer intervenes in the context of municipal supervision. Indeed, Article 280 bis , paragraph 1 of the New Municipal Law only provides that the governor alone exercises the powers provided for in Articles 175, 191, 193, 228 and 229. However, these articles, which concern the governor's competence in security matters, have been removed from the New Municipal Law as part of the restructuring of the Belgian police force.

In order to carry out his duties, the provincial governor has staff at his disposal, some of which are provided by the federal state and some by the region. The governor of the Brussels-Capital Region is not a member of the College of Provincial Governors.

The lieutenant governor

The function of vice governor existed before the division of the former province of Brabant . This vice-governor exercised his powers throughout the province of Brabant, including Brussels. After the division, the function of vice governor was retained in the bilingual Brussels-Capital area, while an “associate governor” was installed in the province of Flemish Brabant (the presence of this “associate governor” can be determined by the necessary protection of the francophone minority in the province Flemish Brabant - which is in the majority in the suburbs of Brussels, however).

The Vice-Governor is a federal commissioner who is “responsible for overseeing the application of the laws and regulations governing the use of languages in administrative matters in the municipalities of the Brussels-Capital administrative district”. He has administrative oversight which enables him to suspend the decisions of the Brussels municipalities for a fortnight if necessary. He also acts as a mediator, taking complaints of non-compliance with language legislation and trying to reconcile the plaintiff and the authority concerned. In the absence of the governor, the lieutenant governor also exercises this office.

Responsibilities of the federal state

Articles 45 and 46 of the special law of 12 January 1989 enable the federal state to exercise a kind of “administrative supervision” over the Brussels-Capital Region as soon as “the international role of Brussels and its function as capital ” are affected. The federal government can suspend the decisions made by the region in the exercise of Article 6, § 1, I, 1 ° and X of the special law of August 8, 1980 in matters of town planning , spatial planning , public works and transport and the Chamber of Deputies can declare them null and void . The federal government can also submit to a “cooperation committee” the measures that it believes the region should take to promote the international statute and function as a capital city.

Regulations on the use of languages

The rules on the use of languages in the bilingual Brussels-Capital area are the responsibility of the federal state. Article 129, § 2 of the Constitution limits the competence of the French and Flemish Communities, which are normally responsible for the use of languages in administrative, educational and labor law matters, to the sole French and Dutch language area.

Article 30 of the Constitution expressly provides for the use of languages by private individuals to be completely free. So nobody can be forced to speak a certain language in everyday life (in the family, at work, etc.). The rules on the use of languages only concern the conduct of public institutions towards citizens or towards other public institutions. These rules are set out in the coordinated legislation of July 18, 1966 on the use of languages in administrative matters.

The coordinated legislation distinguishes between “local” and “regional” agencies. However, in the bilingual Brussels-Capital area, the rules on language use by local and regional services are exactly the same.

- Public : Brussels services prepare notices, communications and forms intended for the public in French and Dutch. These include B. the posting of a building permit , a labeled traffic sign or the invitation to tender for a public contract in the "Official Journal of Tenders". Publications relating to civil status are only made in the language of the document to which they refer.

- Individuals : These services use the language they speak, whether French or Dutch, in their dealings with individuals.

- Registry office : Brussels offices draw up documents relating to private individuals and certificates, declarations and authorizations for private individuals in French or Dutch, depending on the request of the interested party.

- Other services in the rest of the country: Brussels-Capital agencies use the language of this area in their relations with agencies in the French or Dutch language area.

The behavior of a Brussels service towards the other services in the bilingual area of Brussels-Capital is provided for in extremely detailed legislation:

- A. If the matter is limited or limitable:

- exclusively to the French or Dutch language area: the language of this area,

- simultaneously on Brussels-Capital and on the French or Dutch language area: the language of this area,

- simultaneously to the French and Dutch language area: the language of the area in which the matter originates,

- simultaneously to the French and Dutch-speaking areas and to Brussels-Capital, if the matter originates in one of the first two areas: the language of that area,

- simultaneously to the French and Dutch-speaking areas and to Brussels-Capital, if the matter originates in the latter: the language prescribed under letter B) below,

- exclusively in Brussels-Capital: the language prescribed under letter B) below,

- B. If the matter is neither limited nor delimitable:

- if it relates to an employee of a service: the language in which he took his entrance examination or, in the absence of such an examination, the language of the group to which the person concerned belongs because of his main language,

- if it was introduced by a private person: the language that this person used,

- in all other cases: the language in which the staff member who is entrusted with the matter passed his admission test. If this employee has not passed an admission test, he will use his main language.

The Civil Service Law provides that in the offices of the bilingual region of Brussels-Capital a balance between officials whose mother tongue is French or Dutch, must exist. Given that the vast majority of citizens in the Brussels-Capital Region are more likely to be French-speaking, this equilibrium division creates major problems in recruiting civil servants and “filling out” the cadre. In any case, the officials must take a language test in the "other" language (reference is the language of the diploma).

A "permanent language control commission" monitors the correct implementation of the legislation on the use of languages.

See also

- Political system of Belgium and in it u. a. also:

- the Flemish Region , which includes the Dutch-speaking area

- the Walloon region , which includes the French and German language areas

literature

- C. Hecking: The Belgian political system . Leske and Budrich, Opladen 2003, ISBN 3-8100-3724-9 .

Belgian literature

- A. Alen: De derde staatshervorming (1988–1989) in three fasen . In: TBP , special number, 1989.

- J. Brassine: Les nouvelles institutions politiques de la Belgique . In: Dossiers du CRISP , No. 30, 1989, ISBN 2-87075-029-3 .

- J. Clement, H. D'Hondt, J. van Crombrugge, Ch. Vanderveeren: Het Sint-Michielsakkoord en zijn achtergronden . Maklu, Antwerp 1993, ISBN 90-6215-391-7 .

- F. Delperee (dir.): La Région de Bruxelles-Capitale . Bruylant, Brussels 1989, ISBN 2-8027-0455-9 .

- P. Nihoul: La spécificité institutionalnelle bruxelloise . In: La Constitution fédérale du 5 may 1993 . Bruylant, Brussels 1993, ISBN 2-8027-0851-1 , pp. 87 ff.

- Ph. De Bruycker: La scission de la Province de Brabant . In: Les institutional reforms de 1993. Vers un fédéralisme achevé? Bruylant, Brussels 1994, ISBN 2-8027-0883-X , p. 227 ff.

- P. van Orshoven: Brussel, Brabant en de minderheden . In: Het federale België na de vierde staatshervorming . Die Keure, Bruges 1993, ISBN 90-6200-719-8 , p. 227.

Web links

|

Further content in the sister projects of Wikipedia:

|

||

|

|

Commons | - multimedia content |

|

|

Wikinews | - News |

|

|

Wikivoyage | - Travel Guide |

- Brussels Capital Region website (multilingual)

- Website of the Parliament of the Brussels-Capital Region (multilingual)

Individual evidence

- ↑ La Région bruxelloise a 20 ans - Une Région, non peut-être . Lalibre.be, January 12, 2009 (French)

- ↑ La Région bruxelloise a 20 ans - Bruxelles, un modèle pour la Belgique . Lalibre.be, January 12, 2009, interview with Charles Picqué (French)

- ↑ Art. 2, § 1 of the special law of January 12, 1989 on the Brussels institutions ( BS , January 14, 1989)

- ↑ La Région Bruxelloise a 20 ans - 19 communes. Et demain, plus, moins? Lalibre.be, January 12, 2009 (French)

- ↑ Stedelijk gebied van Brussel in the Dutch-language Wikipedia

- ↑ Proposition de loi Visant l'élargissement de Bruxelles . Lalibre.be, September 25, 2007 (French)

- ↑ Maingain: poursuivre les negociations en réclamant toujours l'élargissement . Lalibre.be, April 21, 2010 (French)

- ↑ Article 4 of the special law of January 12, 1989 on the Brussels institutions

- ↑ Article 5 of the Special Act of August 8, 1980

- ↑ Article 136 of the Constitution

- ↑ In Belgium the so-called "territoriality principle" applies, which - according to the Court of Arbitration (today the Constitutional Court ) - gives the communities the authority over a certain area (not over certain persons); see judgment of the Court of Arbitration No. 17/86 of March 26, 1986 and the following “Carrefour” judgments

- ↑ Art. 163, Paragraph 1 of the Constitution

- ↑ Art. 166, § 3, 2 ° of the Constitution

- ↑ Art. 166, § 3, 1 ° and 3 ° of the Constitution

- ^ Fr. Tulkens: La Communauté française, recépage ou dépeçage . In: La Constitution fédérale du 5 may 1993 . Bruylant, Brussels 1993, p. 110 ff.

- ↑ Decree I of Fr. Gem. Of July 5, 1993 and Decree II of Fr. Gem. Of July 19, 1993 transferring the exercise of certain competences to the Walloon Region and the French Community Commission (both BS , September 10, 1993)

- ^ For example, the approval of the COCOF to the European treaties is required before the approval of the Kingdom of Belgium can become final and the treaty can come into force; see e.g. B. the decree of the COCOF of July 17, 2008 approving the European Treaty of Lisbon ( BS , August 26, 2008).

- ↑ See u. a. the statement of the responsible minister in the discussion of the draft of the special law in the Senate Committee ( Parl. Doc. , Senate, 2000-2001, No. 2-709 / 7, esp. p. 263 ff.); readable on the official website of the Belgian Senate

- ↑ Judgment of the Court of Arbitration No. 35/2003 of March 25, 2003; readable on the official website of the Constitutional Court

- ↑ Article 166, § 3, No. 3 of the Constitution

- ↑ Art. 83 of the special law of January 12, 1989 on the Brussels institutions

- ↑ In contrast to the community competences of “common interest” mentioned in the previous paragraph, these are only common personal issues, not cultural or teaching-related.

- ^ Only the state secretaries do not belong to the COCOM / GGC.

- ↑ Art. 165, Section 1, Paragraph 1 of the Constitution

- ↑ Art. 1 of the law of July 26, 1971 on the organization of municipal agglomerations and federations ( BS , August 24, 1971)

- ↑ Art. 166, § 2 of the Constitution and Art. 48 ff. Of the special law of January 12, 1989 on the Brussels institutions

- ↑ Art. 4, § 2 of the law of 26 July 1971 on the organization of municipal agglomerations and federations

- ↑ Art. 6, § 1, VIII, 1 °, of the special law of 8 August 1980 on institutional reforms

- ↑ Art. 6, § 1, VIII of the special law of August 8, 1980 on institutional reforms

- ↑ Ordonnance of July 17, 2003 amending the New Municipal Law ( BS , October 7, 2003)

- ↑ Law of 7 December 1998 on the organization of an integrated police service structured on two levels ( BS , 5 January 1999)

- ↑ Art. 131 bis of the Provincial Law of April 30, 1936

- ↑ Article 65 of the coordinated laws on the use of languages in administrative matters of July 18, 1966

- ↑ Art. 5, § 2 of the Provincial Law of April 30, 1936

- ↑ These “regions” should not be confused with the regions provided for in Article 3 of the Constitution (Flemish Region, Wallonia Region, Brussels Region). In terms of language legislation, the communities and even the federal state are also “regions”.

- ↑ Art. 35, § 1 of the coordinated legislation of July 18, 1966 on the use of languages in administrative matters ( BS , August 2, 1966); these rules are contained in articles 17 to 22 of the coordinated legislation.

- ↑ Art. 60 ff. Of the coordinated legislation of July 18, 1966 on the use of languages in administrative matters