Janusz Korczak

Janusz Korczak , actually Henryk Goldszmit (born July 22, 1878 or 1879 in Warsaw ; † after August 5, 1942, probably on August 6 or 7 in the German Treblinka extermination camp , official date of death August 7, 1942 ), was a Polish military and pediatrician as well as children's book author and important pedagogue . He was best known for his commitment to children, especially in an orphanage . For example, he accompanied the children of his orphanage when they were deported by the German occupiers to an extermination camp , although that meant death for himself too.

Life

Goldszmit grew up as the first child of Cecilia, nee Gębicka, and Józef Goldszmit with a younger sister Anna in Warsaw.

The wealthy family of lawyers Goldszmit was considered assimilated and lived under the influence of the Jewish Enlightenment movement Haskala . It was only in times of growing anti-Semitism that Henryk began to deal with his Jewish ancestry.

Goldszmit completed his school years in a humanistic grammar school in Warsaw, where he learned Latin , German , French and ancient Greek ; The language of instruction was Russian , as Warsaw was part of the Russian Empire due to the partition of Poland in the 18th century. In 1896, with the illness and the death of his father in a nervous hospital, the family's financial situation deteriorated dramatically, so that the young Henryk had to help finance his living with tutoring. In the same year, as a high school student, he won a young talent award for his first novel The Gordian Knot .

Career

Goldszmit studied medicine at the Imperial University of Warsaw from 1898 to 1904 , and received his license to practice medicine in 1905. He remained active as a writer, however, in 1899 he won a literary competition with a drama under the pseudonym Janusz Korczak . Actually Janasz Korczak - named after the title character of Kraszewski's novel Janasz Korczak and the beautiful sword sweeper - the name became Janusz Korczak due to a misprint , which he then kept. In 1901 the story Kinder der Straße was published , in which he worked on the fate of street children for the first time . The first novels made him so well known that he became a fashion doctor.

After receiving his doctorate , he got a job at a Warsaw children's clinic (1904–1911). His activity there was interrupted in 1904/1905 when he had to serve as a field doctor in the Russo-Japanese War , as well as during two stays abroad for further training (one year in Berlin and half a year in Paris ).

Commitment to children

The additional income from his literary work should benefit his medical and social commitment to poor and neglected children. He often drove to the summer colonies as an unpaid carer - summer holiday camps for children of the urban proletariat financed by donations. When he was offered the management of a new Jewish orphanage built according to his plans in 1912 , he gave up the medical profession and accepted.

The Dom Sierot ( Polish orphanage ) became his life. Supported by the Jewish Society for Help for Orphans , the house took in Jewish children up to the age of 14. Korczak was given the educational leeway to implement his ideas based on fundamental children's rights and to look for new ways, for example in the implementation of a children's republic model. When he was called up again as a division doctor in the Russian army after the outbreak of World War I , his colleague Stefania Wilczyńska (known as Stefa ) continued the work in Dom Sierot . But Korczak continued to work as a pedagogue: On the one hand, he wrote his most important educational work with How to Love a Child , and on the other hand, he took care of several orphanages during his stay near Kiev, where he met Maryna Falska , who ran a boarding school for Polish children there .

The following period - after the return from the war and the normalization of daily life in Warsaw, which has once again become the capital of the independent Polish state - can be described as Korczak's heyday. In addition to his work at Dom Sierot , in 1919, together with Maryna Falska, he also took over the management of the orphanage Nasz Dom ( Our House ), which, initially housed in Pruszków near Warsaw, was able to move to the Warsaw villa suburb of Bielany in 1928 . An alternative school was attached to this for two years . He also worked as a lecturer at the Institute for Special Education , from 1926 as an expert on educational issues at the district court and from 1926 to 1930 as editor of the children's newspaper Mały Przegląd ( Kleine Rundschau ). In 1926 he had also joined the Masonic Lodge Gwiazda Morza (under the obedience of Le Droit Humain ) in Warsaw. He wrote numerous books in which he described his experiences and ideas - far more often in children's books and stories than in educational writings. Finally, he became an employee of the Polish radio in 1935/36 when he chatted with children and about children in front of the microphone, albeit not under his name, but only as an “old doctor”.

Activity in the Warsaw Ghetto

In connection with the open anti-Semitism that was spreading in society, Korczak dealt with Zionism in the mid-1930s , traveled to Palestine twice (1934 and 1936) and considered emigration, which he ultimately rejected.

In September 1939 the Second World War began with the invasion of Poland in Europe . In accordance with the anti-Semitic ideology of National Socialism , massive oppression, disenfranchisement and persecution of the Jews began, which resulted in the extermination of the Jewish Polish population , the unprecedented genocide of them. After the order for the compulsory and immediate resettlement of the entire Jewish population of Warsaw to the assembly camp of the Warsaw Ghetto in October 1940, the Dom Sierot had to move as the building was just outside the specified city quarter. Despite the unspeakable conditions in this prison camp, Korczak found the energy to take notes in recent months. His Pamiętnik , which was saved and was first published in 1958 by Igor Newerly , is a mixture of memoirs, diary-like descriptions of the present of the camp known as the ghetto as well as visions of the future and interpretations of dreams.

Deportation and death

In August 1942, as part of the actions were the so-called " final solution " that about 200 children of the orphanage by the SS for deportation to the death camp Treblinka picked up. Although Korczak knew that this would mean death, he did not want to abandon the children and, like his colleague Stefania Wilczyńska, insisted on going with them. The composer and pianist Władysław Szpilman was an eyewitness to the evacuation and describes the scene in his memoir:

“One day, around August 5th [...] I happened to witness Janusz Korczak and his orphans leaving the ghetto. For that morning the 'evacuation' of the Jewish orphanage, of which Janusz Korczak was director, had been ordered; he himself had the chance to save himself, and it was only with difficulty that he got the Germans to allow him to accompany the children. He had spent many years of his life with children and even now, on the last journey, he did not want to leave them alone. He wanted to make it easier for them. They were going to the country, a cause for joy, he explained to the orphans. At last they could trade the hideous, stuffy walls for meadows where flowers grow, for streams in which one could bathe, for forests where there were so many berries and mushrooms.

He ordered them to dress for festive occasions and so nicely dressed up, in a happy mood, they went up in pairs in the courtyard. The small column was headed by an SS man who, as a German, loved children, even those whom he would shortly send to the afterlife. He particularly liked a twelve-year-old boy, a violinist, who carried his instrument under his arm. He ordered him to step up to the head of the children's procession and play - and so they set off. When I met them on Gęsia Street, the children were beaming, singing in a choir, the little musician played them and Korczak was carrying two of the little ones, who were also smiling, in his arms and telling them something funny. Certainly the 'old doctor' was still in the gas chamber when the cyclone was already choking the child's throats and fear replaced joy and hope in the hearts of the orphans, whispering with his last effort: 'Nothing, that's nothing, children' at least to spare his little pupils the horror of the transition from life to death. "

His exact date of death is unknown. Korczak's diary entries end on August 5, 1942.

In 1954, a Polish court set Korczak's death date as May 9, 1946, one year after the end of the war. This date was used for all those who died during the war whose exact date of death is not known. In 2012, the Lublin District Court set August 7, 1942 as the date of death. The change was requested by Fundacja Nowoczesna Polska (Modern Poland Foundation), which wanted to make Korczak's works freely available online. The change made Korczak's works in the public domain four years earlier, in 2012 instead of 2016 .

Afterlife and effects

- In 1957 Erwin Sylvanus ' play Korczak und die Kinder , which is one of the most frequently performed German post-war plays, premiered.

- In 1963, Shmuel Gogol , Auschwitz survivor and former orphan under Korczak's care, founded the Children's Harmonica Orchestra of Ramat Gan , Israel, also to continue Korczak's music education work.

- In 1975 the Polish director Aleksander Ford filmed it as a German-Israeli co-production under the title You are free, Dr. Korczak the story of Janusz Korczak with Leo Genn in the lead role.

- In 1980, the Bullenhuser Damm school in Hamburg , where in April 1945 20 children on whom Kurt Heissmeyer had carried out human experiments in Neuengamme concentration camp and at least 28 adults were murdered, was named after him. A little later, neo-Nazis carried out an attack on the building.

- In 1988, at DEFA Studio for Documentary Films , Berlin, a biographical film essay by Walther Petri and Konrad Weiß was created about Janusz Korczak with the title I am small, but important .

- 1990 filmed the Polish director Andrzej Wajda Korczak's life story. Wojciech Pszoniak played the title role in the German-Polish coproduction Korczak, based on a script by Agnieszka Holland .

- In 1995 the youth novel Im Schatten der Mauer appeared. A novel about Janusz Korczak (original title: Shadow of the Wall ) by Christa Laird .

- In 1996 Karlijn Stoffels published the youth novel Mosje en Reizele ( Mojsche and Rejsele ), a love story in Korczak's orphanage during the German occupation.

- On the occasion of the German Evangelical Church Congress in 1997, the Wülfrath group wrote a " tragical " called a musical called In the Shadow of the Wall , which is based on the novel by Christa Laird and depicts the last three years of the children's home in the Warsaw ghetto. It was also performed in Israel.

- In 2011, a group of young people and adults from the Evangelical Reformed parish Johannes in Bern wrote a dialect play about the life of Korczak under the title Geraniums in the Ghetto - Janusz Korczak, a life for children .

Honors

- Peace Prize of the German Book Trade 1972

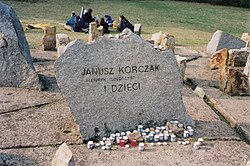

- Bronze statue of Korczak and the ghetto children on the square named after him in Yad Vashem ( Boris Saktsier , 1978)

- In 1978 the International Korczak Society was founded with its headquarters in Warsaw. There are also various national Korczak companies.

- On April 1, 1980, an asteroid was named after him: (2163) Korczak

- Numerous schools and institutions for children in Germany are named after Janusz Korczak.

- In the Hanoverian district of Bult , the avenue leading to the traditional children's sanatorium bears his name.

- In the Berlin district of Hellersdorf , a newly laid street has been named after him since November 20, 1995.

- Also in Berlin, in the Pankow district , a library was named after Janusz Korczak.

- In Luxembourg, the Kannerschlass Foundation in Zolwer has awarded the Prix Janusz Korczak every two years since 1993 to honor people for exceptional services in the social field.

- In 2003, a bronze monument by Itzchak Belfer was erected in Günzburg in his honor.

- There are numerous monuments to Korczak in Poland, many of them in Warsaw, e.g. B. the one on the square on the north side of the Kulturpalast .

- Foundation of the European Janusz Korczak Academy eV (EJKA) in Munich in 2009 to promote Jewish youth and adult education as well as interreligious dialogue.

- Various prizes were named after Janusz Korczak.

Works (selection)

Complete edition

- Janusz Korczak's Complete Works appeared between 1996 and 2005 in German translation at the Gütersloh publishing house, edited by Friedhelm Beiner and Erich Dauzenroth, in 16 volumes and a supplementary volume (with the memories of contemporary witnesses), provided with numerous biographical and bibliographical information.

Children's books

- King Hänschen the First (also: King Maciuś the First ; Polish first edition Król Maciuś Pierwszy 1923 ), 1988

- King Hanschen on the lonely island ( Polish first edition Król Maciuś na wyspie bezludnej 1923 )

- When I'm little again ( Polish first edition Kiedy znów będę mały 1925 )

- Jack acts for everyone ( Little Jack's bankruptcy ; 1924 )

Educational writings

- How to love a child ( Polish first edition Jak kochać dziecko 1919 ), 1967.

- The child's right to respect ( Polish first edition Prawo dziecka do szacunku 1928 )

- The rules of life ( Polish first edition Prawidła życia 1930 )

- Happy pedagogy ( Polish first edition Pedagogika żartobliwa 1939 )

Briefs

How to love a child ( Polish first edition Jak kochać dziecko 1919 ), Korczak's most important educational work, consists of four parts. The first part accompanies the child and its upbringing from birth to puberty. Korczak observes, describes and formulates his views in each case.

- "I want you to understand: no book and no doctor can replace your own waking thinking, your own careful consideration."

The second part, The Boarding School , is aimed at young educators: Korczak reports on his experiences in educational work. Here, too, he emphasizes the attention to the individuality and personality of both the educator:

- "Have courage for yourself and find your own way."

as well as the child:

- "It is one of the most vicious mistakes to assume that education is the science of the child - and not the science of humans first."

In the third part, Summer Colonies , Korczak reports on his first (sobering) educational experiences in the summer colonies. The fourth part, The Orphanage , finally deals with pedagogical ideas implemented in the orphanage, such as institutions of self-administration.

King Hänschen the First or King Maciuś the First ( Polish first edition Król Maciuś Pierwszy 1923 ) is Korczak's best-known book and is equally suitable for children and adults. When Hänschen / Maciuś, a ten-year-old boy, becomes king after the death of his father, he takes on the title of “King-Reformer”, who introduces democracy for the entire nation , including children. The story then plays through the idea of a children's parliament , which is both funny and serious , showing itself to be inventive and capable of learning, reforming its own rules again and again, but also having to deal with hostile influence and questions of internal and external peace. In the first volume the parliament fails, King Hänschen loses the war against the enemy and is exiled by the victors, but has also gained valuable allies.

In the sequel to King Hänschen on the lonely island (included in King Maciuś the first as the second part) ( Polish first edition Król Maciuś na wyspie bezludnej 1923 ), Hänschen thinks a lot about life and the mistakes he has made. He escapes from the island and after a long odyssey returns to his capital, where he abdicates in order to work and learn as a normal mortal.

The book can also be read as a detailed illustration of Korczak's pedagogical reform approach to orphanage self-administration.

When I'm little again ( Polish first edition Kiedy znów będę mały 1925 ) is a first- person story. The narrator starts out as an adult, a teacher who wishes to return to a carefree, carefree childhood - on one condition:

- “If I were a child again, I would like to keep everything in my mind, to know and be able to do everything that I know and can now. And that nobody notices that I was already big. "

This wish is fulfilled for him by a dwarf and the internal action begins. The reader accompanies the boy through his life, he learns of his beautiful and bad experiences and of his worries and problems, which repeatedly distract him from the school material. One experiences the superficiality and injustice of adults in dealing with children.

The foreword to the adult reader reads:

You say,

“We are tired of dealing with children.”

You are right.

You say,

“Because we have to descend to their conceptual world.

Go down, lean down, bend, make smaller. ”

You are wrong.

Not that tires us. But - that we have to climb up to their feelings. Climb up, stretch out, stand on tiptoe, reach out.

So as not to hurt.

In Korczak's work “How to love a child” from 1919 he formulated three basic rights for children in the chapter “How to love a child”:

"I call for the Magna Charta Libertatis as a basic law for the child. Perhaps there are others - but I have found out these three basic rights:

- The child's right to his own death

- The child's right to this day

- The child's right to be what they are. "

In another paper from 1929 he formulated a fourth right, which as a basis summarizes the first three rights: 4. The child's right to respect.

The child's right to his own death, which at first glance seems very strange, only becomes more understandable if it is read as a criticism of an educational atmosphere dominated by fear. Korczak criticizes an upbringing that prevents the child from having independent experiences through oversupply and long-term prevention: "You just have to have the courage to take on a little fear for his life". He combines two interlinked demands: The adults must stay away from unnecessary paternalism, threatening practices and mistrust and allow the child the ability to act by allowing the child to take on decision-making and responsibility.

With the “right of the child to this day”, Korczak speaks out against future-oriented ideas about upbringing: “For the sake of the future, little attention is paid to what makes the child happy, sad, astonished, angry and interested today. For this morning, which it neither understands nor needs to understand, one cheats it of many years of life "

With the “right of the child to be as it is” Korczak means that children cannot be re-educated at will and have an unchanging nature which cannot be changed overnight even through educational measures: “You can be lively not forcing aggressive child to be sedate and quiet; a suspicious and closed one will not become open and talkative, an ambitious and unruly one will not become gentle and indulgent "

The child's right to respect ( Polish first edition Prawo dziecka do szacunku 1928 ) is the summary of a series of lectures by Korczak and can be characterized as a pamphlet in which he makes himself the child's advocate. He describes childhood as a phase of lawlessness, injustice and dependencies, in order to then vehemently demand fundamental rights for the child (a thought that already appears in How to love a child and is further developed here). He formulates the right to respect for childhood as a full phase of life and specifies this in various individual rights such as

- Respect for the child's ignorance

- Respect for the child's curiosity

- Respect for the child's failures and tears

- Respect for the child's property

as well as the child's right to be who they are.

The rules of life ( Polish first edition Prawidła życia 1930 ) has the subtitle A guide to education for young people and for adults . Korczak himself describes the basic idea of the book at the beginning:

- »[...] one day a boy noticed:

- We have a lot of grief because we don't know the rules of life. Sometimes adults calmly explain something to you, but often they are unwilling.

- [...]

- I took a piece of paper and wrote down:

- 'The Rules of Life'.

- [...]

- The boy is right - that's it.

- And I made a plan.

- I want to write about life at home, about parents, brothers and sisters, about joys and sorrows at home.

- Then across the street.

- Then about school. "

Happy Pedagogy ( Polish first edition Pedagogika żartobliwa 1939 ) collects the pedagogical radio chats of the "Old Doctor" that the Polish Radio broadcast in the mid-1930s. In each chapter Korczak tells stories from the child's life on a specific topic and at the end formulates a kind of pedagogical conclusion .

Secondary literature

- Friedhelm Beiner: Janusz Korczak - topics of his life. A work biography. Gütersloher Verlagshaus, Gütersloh 2011, ISBN 978-3-579-06561-8 .

- Susanne Brandt: Flights of thought without illusion. Janusz Korczak as a source of inspiration for dialogic encounters with children . With a contribution by Michael Kirchner. Fantastic Library, Wetzlar 2010, DNB 1007601353 (= publication series of the Center for Literature , Volume 10).

- Irène Cohen-Janca, Maurizio AC Quarello (Illustrator): The Last Journey. Doctor Korczak and his children (original title: L 'ultimo viaggio, il dottor Korczak ei suoi bambini , translated by Edmund Jacoby). Publishing house Jacoby & Stuart , Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-942787-55-0 .

- Erich Dauzenroth , Adolf Hampel (ed.): Who was Janusz Korczak. 8 lectures and one feature . Justus Liebig University Giessen, Giessen 1975 ( digitized version ).

- Erich Dauzenroth: A life for children. Janusz Korczak . 5th, revised edition, Gütersloher Verlagshaus, Gütersloh 2002, ISBN 3-579-01042-5 (= Gütersloher paperbacks , volume 1042).

- Barbara Engemann-Reinhardt: My way with Korczak - experiences of a collector . In: Siebert, Irmgard (Hrsg.): Library and research: the importance of collections for science . Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 2011, ISBN 978-3-465-03685-2 , pages 11-28.

- Rosemarie Godel-Gaßner, Sabine Krehl (Ed.): Children are (only) people too. Janusz Korczak and his pedagogy of respect. An introduction . IKS Garamond, Jena 2011, ISBN 978-3-941854-60-4 .

- Lorenz Peter Johannsen: Janusz Korczak. Pediatrician. Hentrich & Hentrich, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-95565-110-7 (= Jewish miniatures , volume 174).

- Janusz Korczak: Diary from the Warsaw Ghetto 1942 . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1996, ISBN 3-525-33579-2 .

- Ferdinand Klein: Janusz Korczak. His life for children - his contribution to curative education. (1st edition 1996), 2nd edition, Klinkhardt, Bad Heilbrunn 1997, ISBN 3-7815-0814-5 .

- Ferdinand Klein: Shaping inclusion with Janusz Korczak. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2018, ISBN 978-3-525-71143-9

- Friedrich Koch : The dawn of pedagogy . Worlds in your head: Bettelheim, Freinet, Geheeb, Korczak, Montessori, Neill, Petersen, Zulliger. Rotbuch-Taschenbuch 1090, Hamburg 2000, ISBN 3-434-53026-6 .

- Friedrich Koch : Three reasons to deal with Korczak . In: Pedagogy , 1991, No. 10, page 53 ff.

- Betty Jean Lifton: The King of Children. The life of Janusz Korczak . (New York 1988) From the American by Annegrete Lösch. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1990, ISBN 3-608-95678-6 ; Paperback edition: Heyne, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-453-08768-2 .

- Hanna Mortkowicz-Olczakowa: Janusz Korczak, doctor and educator . Pustet, Munich / Salzburg 1973, DNB 750177640 .

- Wolfgang Pelzer: Janusz Korczak . Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1987, 9th edition 2004, ISBN 3-499-50362-X .

- Monika Pelz : I don't want to save myself! - The life story of Janusz Korczak , Weinheim, Beltz 1998, ISBN 978-3-407-78902-0 .

Movies

- The stones wept - about the life and death of Janusz Korczak. Documentary, Germany, 2008, 15 min., Script and director: Franz Deubzer, production: Argus Film, Bayerischer Rundfunk , first broadcast: July 22, 2008 in BR-alpha

- Korczak . Biography drama, Poland, Federal Republic of Germany, Great Britain, 1990, 112 min., Book: Agnieszka Holland , director: Andrzej Wajda , camera: Robby Müller , music: Wojciech Kilar , production: Perspektywa, Regina Ziegler Filmproduktion, Telmar, Erato, ZDF , BBC , Film data from the Lexicon of International Films .

- You are free, Dr. Korczak. Literature adaptation, BR Germany, Israel, 1975, 99 min, book: Joseph Gross, director: Aleksander Ford , producer: Artur Brauner , CCC Filmkunst, ZDF , Bar Kochba, film data from the Lexicon of International Films .

- L'adieu aux enfants. (TV 1982), 91 min, book: Alain Buhler, director: Claude Couderc.

- Król Maciuś I (King Maciuś the First) (1957), 89 min, novel: Janusz Korczak, book: Igor Newerly , Wanda Jakubowska , director: Wanda Jakubowska, leading role: Juliusz Wyrzykowski .

Web links

- Literature by and about Janusz Korczak in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Janusz Korczak in the German Digital Library

- janusz-korczak.de

- Swiss Janusz Korczak Society

- Korczak Collection of the University and State Library Düsseldorf

- Life stages in pictures ( English )

- Dieter Reifarth: Janusz Korczak - 1942 - 15 min… , Hessischer Rundfunk 1987 (video)

- Siegfried Zimmer : Janusz Korczak , lecture Weimar April 30, 2017

References and comments

- ↑ The exact year of birth is not known. Korczak writes in his Pamiętnik : “For years my father did not bother to get a birth certificate for me. Later I had difficulties because of this. ”Quoted in the German translation by Armin Droß in: Elisabeth Heimpel , Hans Roos (Ed.) The child's right to respect . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1970. p. 332.

- ^ Changed date of death shows Janusz Korczak was killed in Treblinka. Jerusalem Post, March 30, 2015, accessed August 5, 2017 .

- ↑ Cf. Friedhelm Beiner (2008): What children are entitled to. Janusz Korczak's pedagogy of respect. Content - Methods - Opportunities . Gütersloher Verlagshaus, Gütersloh 2008, p. 153.

- ^ Christoph Gradmann : Korczak, Janusz. In: Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil , Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , p. 781 f .; here: p. 781.

- ↑ Page no longer available , search in web archives: Pan Doktor in Le Droit Humain Polska , May 2012 (Polish)

- ↑ 'Pamiętnik' means both 'diary' and 'memories'; German published as a diary from the Warsaw Ghetto in 1942 ( see literature ).

- ↑ http://www.yadvashem.org/yv/de/exhibitions/spots_of_light/stefania_wilczynska.asp

- ^ Władysław Szpilman: The pianist. My wonderful survival . Ullstein Munich 2002, ISBN 3-548-36351-2 , pp. 93-94

- ^ Court Determines Janusz Korczak's Date of Death. culture.pl, March 30, 2015, accessed August 5, 2017 .

- ^ Changed date of death shows Janusz Korczak was killed in Treblinka. Jerusalem Post, March 30, 2015, accessed August 5, 2017 .

- ↑ Günther Schwarberg, The SS doctor and the children from Bullenhuser Damm, Göttingen, Editorial Steidl, 1994 edition, ISBN 9783882433067 , pp . 10ff.

- ↑ Film I am small but important ( homepage Konrad Weiß ) / In the cinematography of the Holocaust of the Fritz Bauer Institute

- ^ Film Korczak in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- ↑ Janusz Korczak - the tragical fuenfbroteundzweifische.de

- ↑ Geraniums in the Ghetto. Janusz Korczak - a life for children theaterensemble.ch

- ↑ Elke Heidenreich : Janusz Korczak receives the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade , radio feature for the SWF 1972, print version in: E. Heidenreich: Words from 30 Years . Rowohlt, Hamburg 2003, ISBN 3-499-23226-X , pp. 11–37

- ↑ http://www.friedenspreis-des-deutschen-buchhandels.de/sixcms/media.php/1290/1972_korcak.pdf

- ^ Celebrations in memory of Janusz Korczak in Poland . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung of June 2, 1978.

- ↑ Interactive map of the Janusz Korczak Schools , website of the Janusz Korczak School, Special School of the Steinfurt District, August 24, 2015, accessed on December 13, 2015.

- ^ Janusz-Korczak-Allee in Hanover , strassenkatalog.de

- ^ Janusz Korczak Street. In: Street name lexicon of the Luisenstädtischer Bildungsverein (near Kaupert )

- ^ Janusz Korczak Library in Berlin-Pankow

- ↑ German by Armin Droß. In: Elisabeth Heimpel, Hans Roos (Ed.): The child's right to respect . 3. Edition. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht , ISBN 3-525-31502-3 , Göttingen 1971, p. 2.

- ↑ German by Armin Droß. In: Elisabeth Heimpel, Hans Roos (Ed.): The child's right to respect . 3. Edition. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht , ISBN 3-525-31502-3 , Göttingen 1971, p. 228

- ↑ German by Armin Droß. In: Elisabeth Heimpel, Hans Roos (Ed.): The child's right to respect . 3. Edition. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht , ISBN 3-525-31502-3 , Göttingen 1971, p. 156

- ^ German by Katja Weintraub . Issues first in Warsaw 1957 and Göttingen 1971, ISBN 3-525-39106-4

- ↑ German of Monikar Heinker (Leipzig and Weimar 1978)

- ^ ISBN 3-525-39144-7

- ^ German by Mieczyslaw Wójcicki. In: When I'm little again and other stories from children. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht , Göttingen 1973, ISBN 3-525-31509-0 , p. 13.

- ↑ German by Armin Droß. In: Elisabeth Heimpel, Hans Roos (Ed.): The child's right to respect . 3. Edition. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht , ISBN 3-525-31502-3 , Göttingen 1971, p. 7

- ↑ Janusz Korczak: How to love a child . Ed .: Elisabeth Heimpel, Hans Roos. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1967, p. 40 .

- ^ Wolfgang Pelzer: Janusz Korczak . Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag GmbH, Reinbek near Hamburg 1987, p. 49 .

- ↑ Janusz Korczak: How to love a child . Ed .: Elisabeth Heimpel, Hans Roos. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1987, p. 270 .

- ↑ Friedhelm Beiner: The basic rights of the child as the basis of the pedagogy of respect . Gütersloher Verlagshaus, Gütersloh 2008, p. 28 .

- ↑ Janusz Korczak: How to love a child . Ed .: Elisabeth Heimpel, Hans Roos. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1967, p. 45 .

- ↑ Janusz Korczak: How to love a child . Ed .: Elisabeth Heimpel, Hans Roos. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1967, p. 157 .

- ↑ German by Armin Droß. In: Elisabeth Heimpel, Hans Roos (Ed.): The child's right to respect . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht , Göttingen 1970, ISBN 3-525-31503-1 , p. 96 f.

- ↑ The stones wept over the life and death of Janusz Korczak br.de

- ↑ L'adieu aux enfants (TV 1982). In: International Movie Database. IMDB, accessed June 2, 2013 .

- ↑ L'adieu aux enfants (TV 1982). Retrieved June 2, 2013 (French).

- ^ Król Maciuś I. In: Film Polski. FP, accessed on August 13, 2015 (Polish).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Korczak, Janusz |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Goldszmit, Henryk (maiden name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Polish doctor, educator and children's book author |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 22, 1878 or July 22, 1879 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Warsaw |

| DATE OF DEATH | after August 5, 1942 |

| Place of death | Treblinka extermination camp |