Talmud

The Talmud ( Hebrew תַּלְמוּד, German instruction , study ) is one of the most important written works of Judaism . It consists of two parts, the older Mishnah and the younger Gemara , and is available in two editions: Babylonian Talmud (Hebrewתַּלְמוּד בַּבְלִי Talmud Bavli ) and Jerusalem Talmud (Hebrewתַּלְמוּד יְרוּשָׁלְמִי Talmud Jeruschalmi ). The Talmud itself does not contain any biblical legal texts ( Tanach ), but rather shows how these rules were understood and interpreted by the rabbis in practice and in everyday life .

term

Talmud is one of the Hebrew verb rootלמד lmd , German noun derived from 'learning' . "Teaching" refers to the activity of studying, teaching and learning as well as the subject of the study.

The Aramaic equivalent of the Hebrew root is גמר gmr . From her the term גְּמָרָא gəmārā ' is derived , which also means "teaching".

expenditure

The Talmud is available in two major editions: the Babylonian Talmud (abbreviated: bT) and the Jerusalem Talmud (abbreviated: jT). When speaking simply of the Talmud , the Babylonian Talmud is usually meant.

Babylonian Talmud

The Babylonian Talmud (Hebrew תַּלְמוּד בַּבְלִי Talmud Bavli , Aramaic תַּלְמוּדָא דְבָבֶל Talmuda deVavel ) is the more important work in terms of scope, weight and impact . It originated in the relatively large, closed Jewish settlement areas in Babylonia . These gained in importance after the destruction of Jerusalem by the Romans, because they belonged to the Parthian and later to the Sassanid Empire and were thus outside the Roman or Byzantine sphere of influence. Important schools of scholars, the discussions of which were reflected in the Babylonian Talmud, were in Sura and Pumbedita , and initially in Nehardea as well . The authoritative authors are the rabbis Abba Arikha (called Raw), Samuel Jarchinai (Mar) and Rav Aschi .

Jerusalem Talmud (Palestinian Talmud)

The considerably shorter Talmud Jeruschalmi originated in Palestine . It is less important than the Babylonian Talmud and its provisions are often less strict. According to the Jewish tradition that goes back to Maimonides , Rabbi Jochanan is the most important author . There are different names for the Jerusalem Talmud:

- In ancient times it was originally called תַּלְמוּד יְרוּשָׁלְמִי Talmud Jeruschalmi - or יְרוּשָׁלְמִי Jeruschalmi for short .

- Later names are:

- Hebrew תַּלְמוּד אֶרֶץ יִשְׂרָאֵל Talmud Eretz Yisrael 'Talmud of the Land of Israel '

- Aramaic גְּמָרָא דְאֶרֶץ יִשְׂרָאֵל Gemara deʾEretz Yisrael 'Gemara of the Land of Israel'

- Aramaic תַּלְמוּדָא דְמַעֲרָבָא Talmuda demaʿarava 'Talmud of the West'

- Aramaic גְּמָרָא דִבְנֵי מַעֲרָבָא Gemara divne maʿarava 'Talmud of the Sons of the West'

- Today it is usually called the Talmud Jeruschalmi or Jerusalem Talmud .

- Christian scholars often call it the Palestinian Talmud ; The name Palestinian Talmud is encountered particularly in older literature .

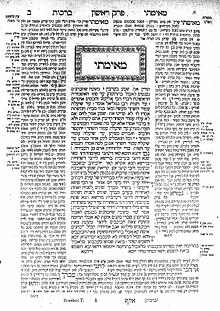

First print

The first print of the Babylonian Talmud from 1523, edited by Jacob Ben Chajim , comes from the printing works of Daniel Bomberg , a Christian from Antwerp who worked in Venice between 1516 and 1539 . The folio numbering introduced by Bomberg is still in use today.

Structure and content

The text of the Talmud can be divided according to various criteria:

Mishnah and Gemara (text basis and commentary)

The basis of the Talmud is the Mishnah ( Hebrew מִשְׁנָה'(Teaching through) repetition'). The Mishnah is the first written down of the oral Torah (תּוֹרָה שֶׁבְּעַל-פֶּה torāh šæbə'l-pæh ), that part of the Torah which, according to Jewish tradition, God is said to have revealed to Moses orally on Mount Sinai and which in the following centuries was initially only passed on orally, but finally codified in the 1st or 2nd century has been. The Mishnah , which was written in Hebrew , found its final form in the 2nd century under the editorial supervision of Yehuda ha-Nasi . It is therefore essentially identical in the Babylonian and Jerusalem Talmuds. In the Talmud manuscripts it is often only given in abbreviated form.

Whenever the Talmud is quoted as such, the Gemara is always meant (Aramaic: גמרא 'doctrine', 'science'), the second layer of the Talmud, so to speak. The Gemara consists of commentaries and analyzes on the Mishnah, alternating in Hebrew and Aramaic . These are the fruit of extensive and deep philosophical discussions among Jewish scholars, particularly in the academies of Sura and Pumbedita . Based on the mostly purely legal issues , connections were made to other areas such as medicine , science , history or education . The more factual style of the Mishnah was also expanded to include various fables , legends , parables , riddles, etc. Most of the scholars cited in the Gemara worked in the 3rd to 5th centuries. The two versions of the Gemara were completed between the 5th and 8th centuries. While the Mishnah is common to both editions of the Talmud, the Gemara of the Babylonian and Jerusalem Talmuds differed considerably.

In manuscripts and prints of the Babylonian Talmud, commentaries from a later period are added as a kind of third layer. In this respect, those of Raschi (Rabbi Schlomo ben Jizchak), a Talmud scholar who worked in France and Germany in the 11th century, should be emphasized .

The constant development of the tradition through discussions, comments and analyzes characterizes the consistently dialectical style of the Talmud. The preferred means of presentation is the dialogue between different rabbinical doctrines, which in the end leads to a decision and reflects the relevant state of the tradition.

The arrangement of the parts of the text on a typical Talmudic page is as follows: The main text in the middle of each page alternates with the Mishnah and Gemara. The text strip on the upper inner edge of a page contains Raschi's comment, the one on the outer edge and, if necessary, on the lower edge, any further comments.

The six orders (factual classification)

A second external classification system is based on factual principles. Both Talmuds, like the Mishnah on which they are based, are in 6 "orders" (סְדַרִים sədarîm , in the singularסֵדֶר sædær ), which in turn are divided into 7 to 12 tracts (מַסֶּכְתֹּות massækhtôt , singularמַסֶּכֶת massækhæt ). The tracts in turn consist of sections and ultimately of individual Mishnayot (plural of Mishnah). This division into "six orders" has led to the name Shas (ש״ס) for the Talmud, which is common in Orthodox Judaism (abbreviation of Hebrew שִׁשָּׁה סְדַרִים šiššāh sədarîm , German 'six orders' ).

The titles of the orders are:

- Seraʿim סֵדֶר זְרָעִים (seeds, seeds) : eleven treatises on agricultural taxes to priests, the socially needy, strangers.

- Mo'ed סֵדֶר מוֹעֵד (feast days, feast days) : twelve treatises on feast days and fast days.

- Naschim סֵדֶר נָשִׁים (women) : seven treatises on family law.

- Nesiqin סֵדֶר נְזִיקִין (injuries) : ten treatises on criminal and civil law, especially compensation law, plus the ethical treatise Avot.

- Qodaschim סֵדֶר קָדָשִׁים (Holy Things) : eleven treatises on sacrificial rites, dietary regulations, etc.

- Toharot סֵדֶר טְהָרוֹת (purifications) : twelve treatises on the purity / impurity of persons, things and places.

Halacha and Aggada (functional differentiation)

The text of the Talmud can be divided into two thematic areas across the board: In addition to the practical interpretation of the legal provisions ( Halacha , הלכה, literally: 'walking'), there are narrative and edifying ( homiletic ) considerations ( Aggada , אגדה, literally: ' Tell'). The latter is found mainly in the Gemara, but hardly in the Mishnah, which consists almost exclusively of Halacha.

In his poem Jehuda Ben Halevy Heinrich Heine compares the Halacha with a "fencing school where the best dialectical athletes [...] played their fighting games". The Aggada, which he wrongly calls " Hagada ", is "a garden, highly fantastic", in which there are "beautiful old sagas, angel fairy tales and legends", "silent martyr histories, celebratory chants, sayings of wisdom (...)".

language

In addition to Hebrew , Aramaic is the language of the Talmud. The Talmud is usually studied in the original languages.

The first and so far only complete and uncensored German translation of the Babylonian Talmud was published by Jüdischen Verlag from 1929 to 1936. The translation is by Lazarus Goldschmidt . This edition comprises 12 volumes. The page structure differs from the usual editions. The Mishnah is set in small caps . Below is the Gemara in the normal sentence. It is always introduced with the word "Gemara" in capital letters. Additional notes on the Mishnah or Gemara are included as footnotes. In the original edition and in the reprints there is only one table of contents per volume, not a complete list for all volumes. These lists also do not reflect the division into sections.

Anti-Judaist and anti-Semitic Talmudic criticism

Since the Talmud was perceived to be very much identified with the essence of Judaism itself, attacks against Judaism were mostly directed against Judaism as well.

Antiquity

At an early stage, Jews were repeatedly forbidden to deal with the religious law. Such a ban is given by rabbinical historiography as one of the reasons for the Bar Kochba uprising . In 553, Emperor Justinian I passed a law prohibiting Jews from studying deuterosis , which was the Mishnah or study of Halacha in general. Pope Leo VI later renewed this ban.

middle Ages

In the Middle Ages, there was greater hostility towards the Talmud. Some of these attacks came from Jews who converted to Christianity . For example, the Talmud disputation in Paris in 1240 was initiated by the convert Nikolaus Donin , who had been put under the spell by the rabbis in 1224 and converted to Christianity in 1236. In 1238 he demanded in a 35-point pamphlet against the Talmud its ban by Pope Gregory IX. As a result of the disputation between Donin and Rabbi Jechiel ben Josef , the first major burning of the Talmud took place in 1242 .

In 1244, Pope Innocent IV initially ordered the destruction of all editions of the Talmud. At the request of the Jews, he revised this judgment in 1247, but arranged for the Talmud to be censored and at the same time appointed an investigative commission from the University of Paris to which 40 experts belonged, including Albertus Magnus . The commission came to another conviction, which was pronounced in 1248.

In another disputation on the Talmud between Pablo Christiani , who converted from Judaism to Christianity, and the Jewish scholar Nachmanides in Barcelona in 1263 , the Spanish king declared Nachmanides the victor. Until the end of the 16th century, disputations, councils and church assemblies were accompanied by bans, confiscations and burning of the Talmud. Pope Julius III had the work confiscated in Rome in 1553 and burned the collected copies publicly on September 9, Jewish New Year's Day . Then came the Inquisition , which recommended the burning of the Talmud to the rulers in all Christian countries in a decree. Jews were to be forced to deliver copies of the Talmud within three days, threatened with loss of property. Christians should be charged with excommunication if they dare to read the Talmud, to keep it safe, or to assist Jews in this matter.

In anti-Judaist publications, passages from the Talmud have been cited to discredit the Jewish religion and tradition. Some of the "quotations" are forgeries. But even the real quotes are usually torn out of context and do not take into account the form of dialogical, often controversial approach to a topic that is prevalent in the Talmud . In the Talmudic discourse , untenable theses (such as: “ Non-Jews are not people”) are often deliberately thrown into the discussion in order to refute them in the dialogue. Anti-Judaists prefer to use such “ theses ” up to the present day, but withhold the following antitheses , so that a falsified overall impression of the religious guidelines of the Talmud and of the Jewish religion as a whole is created.

A rare exception was the humanist Johannes Reuchlin , who is considered to be the first German and non-Jewish Hebraist who learned the Hebrew language and script for better understanding. He published a Hebrew grammar, wrote about the Kabbalah and defended the Talmud and the Jewish scriptures in a dispute with Johannes Pfefferkorn .

Modern times

In 1543, the reformer Martin Luther , in his pamphlet Von den Jüden vnd Jren Lügen , demanded that synagogues and Jewish houses should be burned and all Jewish books, including the Talmud, should be confiscated. But the Catholic Church also put the Talmud on the first index of forbidden books in the Counter Reformation in 1559 .

In the 17th century there were some humanists and Christian Hebraists who took up the Talmud against the anti-Judaism of the time and tried to understand the New Testament and Christianity better with the help of the Talmud and rabbinical literature . In 1629 the Basel theologian Johann Buxtorf the Younger translated the religious-philosophical work Guide of the Indecisive by the medieval Jewish scholar Maimonides and in 1639 completed the Lexicon chaldaicum, talmudicum et rabbinicum begun by his father Johann Buxtorf the Elder . The Anglican theologian John Lightfoot compiled the Talmudic parallels to the New Testament for the first time in Horae Hebraicae Talmudicae from 1685.

The anti-Jewish author Johann Andreas Eisenmenger collected the passages from the rabbinical literature known to him, especially the Talmud, that were likely to discredit Judaism and strengthen anti-Jewish prejudices, and published them in 1700 under the title Discovered Judaism . The work is considered the most popular of the numerous polemics written by Christian authors against rabbinic literature. It also served as a source for August Rohling's inflammatory pamphlet Der Talmudjude , and later for many other representatives of anti-Semitism .

The practice of using the Talmud to denigrate Judaism and the Jews is widespread today in Christian, Muslim or secular anti-Judaism / anti-Semitism.

Text output

- The Babylonian Talmud . Selected, translated and explained by Reinhold Mayer. Wilhelm Goldmann, Munich 1963 (about 600 pages)

- Lazarus Goldschmidt (translator): The Babylonian Talmud , 12 vols., Frankfurt / M. 2002, ISBN 3-633-54200-0 (reprint; originally Berlin 1929-1936)

- I. Epstein, ed., The Babylonian Talmud. Translated into English with notes, glossary and indices, 35 vols., London 1935–1952 (reprinted in 18 volumes London 1961)

- The Schottenstein Edition Talmud Bavli . English edition. Mesorah Artscroll. new York

- The Safra Edition Talmud Bavli. French translation from Mesorah Artscroll Verlag. new York

Concordances

- Chayim Yehoshua Kasovsky, Thesaurus Talmudis. Concordantiae Verborum quae in Talmude Babilonico reperiuntur , 41 volumes, Jerusalem 1954–1982

- Biniamin Kosowsky, Thesaurus Nominum Quae in Talmude Babylonico Reperiuntur , Jerusalem 1976 ff.

See also

- List of mixed natures

- Complete directory of the German-language Talmud edition

- Torah

- Yeshiva

- Klaus (Talmud School)

- Soferim

literature

- Adolf Lewin: The Jewish mirror of Dr. Justus brought into the light of truth . Magdeburg, 1884

- Abraham Berliner: Censorship and Confiscation of Hebrew Books in the Papal States. Based on the Inquisitions files in the Vaticana and Vallicellana . Itzkowski Publishing House, Berlin 1891

- Raphael Rabbinovicz: Diqduqe Soferim. Variae Lectiones in Mischnam et in Talmud Babylonicum . Mayana-Hokma 1959/60 (16 vol .; reprint of the Munich edition 1868–1886).

- Jacob Neusner : The Formation of the Babylonian Talmud (Studia post-biblica; 17). Brill, Leiden 1970

- Moshe Carmilly-Weinberger: Censorship and freedom of expression in Jewish history . Sepher-Hermon-Press, New York 1977, ISBN 0-87203-070-9 .

- Marc-Alain Ouaknin: The burned book. Read the Talmud . Edition Quadriga, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-88679-182-3 .

- Samuel Singer : Parallels in legendary history from the Babylonian Talmud. In: Journal of the Association for Folklore 2, 1892, pp. 293–301.

- Günter Stemberger : Introduction to the Talmud and Midrash . 8th edition Beck, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-406-36695-3 .

- Leo Prijis: The World of Judaism. Religion, history, way of life . 4th edition Beck, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-406-36733-X , p. 55 ff.

- Barbara Beuys : Home and Hell. Jewish life in Europe for two millennia . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1996, ISBN 3-498-00590-1 , p. 114 ff.

- Hannelore Noack: “Unteachable?” Anti-Jewish agitation with distorted Talmudic quotations; anti-Semitic incitement by demonizing the Jews . University Press, Paderborn 2001, ISBN 3-935023-99-5 ( plus dissertation, University of Paderborn 1999).

- Karl Heinrich Rengstorf, Siegfried von Kortzfleisch (ed.): Church and synagogue. Handbook on the history of Christians and Jews. Representation with sources , Volume 1, dtv / Klett-Cotta Munich 1988, ISBN 3-423-04478-0 , pp. 227-233.

- Yaacov Zinvirt: Gateway to the Talmud , Lit, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-8258-1882-1 .

Web links

- The Babylonian Talmud, 12 volumes (Lazarus Goldschmidt, 1929–1936) Online (archive.org)

- Soncino Babylonian Talmud, English Online

- A Page from the Babylonian Talmud (English)

- Overview of contents of the Talmud (comparison of the tracts of the Mishnah, Babylonian and Palestinian Talmuds)

- Babylonian Talmud - BSB Cod.hebr. 95: Scrollable digitized version in the culture portal bavarikon

- Talmud.de (overview with a list of the individual tracts)

- Babylonian Talmud, parchment manuscript, France (?) 1342 Bavarian State Library, signature: Cod.hebr. 95 (online documentation of the manuscript)

- Documentation "Fake Talmud Quotes in Court" (Duisburg Institute for Linguistic and Social Research, DISS)

- Hermann Leberecht Strack : Introduction to the Talmud , JC Hinrichs, Leipzig, here various older editions facsimile from 1887–1904. [Predecessor of Stemberger's introduction]

- "Soncino Babylonian Talmud" - full text of the Babylonian Talmud in the English translation by Rabbi Dr. I. Epstein, 1934

- The Babylonian Talmud - Full text of the Babylonian Talmud in the English translation by Michael L. Rodkinson, 1918

- Günter Stemberger: Talmud. In: Michaela Bauks, Klaus Koenen, Stefan Alkier (Eds.): The Scientific Biblical Lexicon on the Internet (WiBiLex), Stuttgart 2006 ff.

Individual evidence

- ↑ The designation Babylonia or Babel (Hebrew and Aramaic בבל) survived the existence of the neo-Babylonian empire , initially as a province name in the Achaemenid Empire ( satrapy of Babylonia ), later as a landscape name. As the (provincial) capital, Babylon was already in the 4th century BC. First replaced by Seleukia , later by Ctesiphon .

- ↑ Günter Stemberger : Introduction to the Talmud and Midrash .

- ↑ Michael Krupp : Der Talmud / An introduction to the basic script of Judaism with selected texts , Gütersloher Verlagshaus, Gütersloh, 1995, p. 64.

- ↑ Jakob Fromer: The Talmud / History, Essence and Future , P. Cassirer Verlag, 1920, p. 296.

- ^ The Encyclopedia of the Diaspora New edition: the Babylonian Talmud in German, In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung No. 20, January 25/26, 2003, p. 35.

- ↑ Michael Krupp : The Talmud - An introduction to the basic script of Judaism with selected texts, GTB Sachbuch, Gütersloh, 1995, p. 97.

- ^ Willehad Paul Eckert: Third Chapter, in: Karl Heinrich Rengstorf, Siegfried von Kortzfleisch (ed.): Church and Synagogue . Volume 1, pp. 229-231.

- ↑ Günter Stemberger: The Talmud: Introduction, Texts, Explanations , page 304. ISBN 978-3-406-08354-9 online , accessed on August 11, 2011.

- ↑ Christian Blendinger: Church roots of anti-Semitism (Review of: Hannelore Noack: Unbelehrbar? ) ( Memento of the original from September 29, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. ; in: Sonntagsblatt Bayern, 27/2001. Blendinger writes there: “The subject of the investigation is the way Christians deal with the Talmud […] Disfigured Talmudic quotations from the years 1848 - 1932 for the purpose of inciting Jews and Judaism […] But the message of the book is unmistakable: 'The lap is still fertile from which this crept. ' (B. Brecht) It is always frightening for Christians that this bosom was also the 'bosom of the church', which embraced their children like a mother, but excluded those 'outside', especially the Jews, and thus the mass murder in the Hitler Reich not caused, but helped prepare emotionally. "

- ↑ Falsified “Talmud Quotes” - anti-Semitic - anti-Judaist propaganda: examples, backgrounds, texts.

- ↑ Richard S. Levy (Ed.): Antisemitism - A historical encyclopedia of prejudice and persecution, 2005, pp. 599 ff.

- ↑ Günter Stemberger: The Talmud, Introduction - Texts - Explanations, CH Beck, Munich, 4th edition, 2008, p. 305.

- ^ Gotthard German : Eisenmenger, Johann Andreas. In: Isidore Singer (Ed.): Jewish Encyclopedia . Funk and Wagnalls, New York 1901-1906.

- ^ Anti-Defamation League : The Talmud in Anti-Semitic Polemics (PDF; 204 kB). February 2003.