Climb

Climbing is a type of locomotion that is nowadays mainly practiced as a sport and leisure activity on the rock or in the hall in different variants. In most cases, certain climbing routes are climbed through. Usually, the climber is secured against falling by his climbing partner with a rope .

history

Beginnings of climbing

Climbing has always been a form of locomotion used by humans. Rocks have always been climbed, be it for cultural reasons (for example as a religious place) or for practical reasons such as keeping an eye out for animals or enemies . For example, pottery shards were found on the Rabenfels in Franconian Switzerland , which prove that this rock dates back to 800 to 400 BC. Was climbed. The residents of that time already mastered the third level of difficulty . In the Middle Ages , rocks gained increasing strategic importance, exposed rocks were used as surveillance stations to protect against enemies or as signal towers to relay messages. Due to the ascent of more and more inaccessible peaks from around 1800, climbing increasingly had to be done to overcome ridges and rock steps, but this was mostly done technically .

Start of free climbing

The ascent of the Falkenstein in Saxon Switzerland by Schandauer Turner in 1864 is considered the hour of birth of sporty climbing. From around 1890, free climbing developed in Saxon Switzerland , in which attempts are made to completely dispense with artificial aids to move around while climbing ( see also the history of climbing in Saxon Switzerland ). Outside of Saxony, however, this type of climbing was only occasionally noticed at first.

Around the same time, bouldering was started for the first time for sporting reasons . In the Lake District in the UK began Oscar corner stone as one of the first order, while in Fontainebleau called (France) Bleausards climbed the sandstone blocks lying there in the forest. At first, bouldering was seen primarily as training for alpine activities and only developed into an independent field of activity in the following decades.

Technical era

The technical climbing has developed more in the 1920s and used, making the last important unconquered walls of the Alps could be climbed. After the Second World War, increasingly repellent rock faces could be climbed with the help of the newly developed bolt . So it was possible to conquer practically every rock face - with the appropriate expenditure of material and time. This ultimately led to the goal of climbing all the walls in the Direttissima . In the mid-seventies, some alpinists began to criticize technical Direttissima climbing as a dead end and “murder of the impossible”.

Renaissance of free climbing

In the 1950s, John Gill coined bouldering, making it popular as an independent discipline, developing numerous new climbing techniques and introducing magnesia as an aid.

As a result of the increasing focus on performance, sport climbing emerged in the late 1960s and early 1970s based on the idea of free climbing, especially in the USA . West German climbers got to know this type of climbing during visits to the Yosemite Valley (USA) and the Elbe Sandstone Mountains , imported them to Western Europe and developed them further. This finally led to Kurt Albert's red dot idea in 1975 . Since then, all types of climbing have become more and more popular around the world, with systematic training and increasing professionalization leading to enormous increases in performance. In the alpine area too, the style of an inspection or ascent became more and more important. This is expressed in the principle of “By Fair Means”, in which in the context of mountain and climbing expeditions, unnecessary aids and carriers are dispensed with. Today there are more than 400,000 active climbers in German-speaking countries .

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) decided on August 3, 2016 that climbing should be included in the Olympic program. The 2020 Olympic Games had to be postponed by one year due to COVID-19 and will now take place from July 23 to August 8, 2021.

Variants of climbing

The transitions between the individual variants of climbing are fluid, often they cannot be clearly delimited from one another. A distinction must be made between sport-oriented climbing and types of climbing that only serve to reach inaccessible places, as well as professional activities.

Alpine climbing

When Alpinklettern usually several must pitches high rock walls or pillars to be overcome. Since the climbers are completely or partially on their own, depending on the accessibility and extent of the wall, careful route planning and selection as well as knowledge of stand construction , abseiling and rescue techniques are required. Even if alpine climbing can be assigned to free climbing, it may be necessary to use technical climbing in order not to lose unnecessary time in places for which the climber cannot find a free climbable solution and thus endanger the rope team .

With the ever better equipment and the increased level of performance of climbers, the idea of sport is now also finding its way into alpine climbing, which is expressed in the form of so-called alpine sport climbing . Here the attempt is made to push the performance limit higher and higher, even in alpine multi-pitch routes.

Technical climbing

In technical climbing, the rope and a variety of aids - including stepladders and ascenders - are used to move. This type of climbing originated in the years after World War I, peaked in the 1960s, and remained very popular through the 1970s and 1980s. Today technical climbing is only used sporadically, mostly in free climbing attempts to overcome places that cannot otherwise be climbed.

Big wall climbing

The big wall climbing is the Beklettern very high rock walls such. B. those in the Yosemite Valley in the USA, in the Paklenica National Park in Croatia, in Norway or in Pakistan . As a rule, big walls are largely technically implemented. Even if the increased performance of top climbers has meant that some of the former techno lines in Yosemite can now be climbed freely, due to the compactness of the rock - mostly granite - free ascent is a utopia for most aspirants. Since technical climbing is much more time-consuming than free ascent and also requires a huge amount of material, it may be necessary to take food and overnight material with you in order to be able to spend the night on the wall.

Free climbing

When free climbing, only the rock and your own body may be used to move. Ropes and technical aids are only used to protect against falling, but not for locomotion (the term does not , as is often assumed, describe climbing without safety, which is referred to as free solo in this context ). The climbing routes are usually equipped with rock hooks or have to be secured with hooks, wedges , friends or slings .

This type of climbing has been around since the end of the 19th century a. a. practiced in Saxon Switzerland and also in the Eastern Alps. Paul Preuss and Rudolf Fehrmann were outstanding representatives here . The latter defined fixed rules for the first time for the Elbe Sandstone Mountains. In Europe, free climbing, especially in the Alpine region, fell behind with the emerging technical climbing and was only rediscovered in the 1970s and 1980s by Western European climbers who had copied it in Saxon Switzerland and the USA. It is the most popular form of climbing today.

Different variants can be distinguished in free climbing:

Sport climbing

Sport climbing is a variant of free climbing in which the sporty aspect is in the foreground. Sport climbing routes are usually secured with numerous permanently attached safety points to minimize the risk of a fall. Sport climbing is practiced both on artificial facilities ( climbing halls ) and on natural rocks, in so-called climbing gardens . The athletes can compete in regional, national and international competitions , which are mostly carried out on artificial walls.

Indoor climbing

With the increasing popularity of climbing halls in commercial or club-operated hands (especially DAV ), indoor climbing has established itself as a sporting activity for many climbers. An increasing number of climbers see climbing in the hall as a pure recreational sport. Indoor climbing is independent of the weather and offers comfortable access to climbing. In particular, many school facilities also use climbing halls in order to be able to offer varied and safe sports lessons. Indoor climbing enables bouldering , top rope and lead climbing . Indoor climbing has significantly increased the level of performance in climbing competitions in recent years. Thanks to intensive youth work and age-appropriate training, peak climbing performance can be achieved at a very young age. Indoor climbing has opened up new areas for climbing.

Bouldering

Bouldering is climbing boulders at jump height. In bouldering, the focus is usually on shorter (not so high), so-called "(bouldering) problems" that are only a few moves long, some of which require difficult, even unusual movements within climbing. A rope safety device is not necessary for this, so called crash pads are used to cushion falls . In addition to crash pads, the assistance of one or more backup partners, known as spotters, may be necessary. The spotter is not supposed to catch the climber, but simply to ensure that he lands safely on the crash pad and does not injure himself on stony terrain. In the case of heavily overhanging bouldering, the spotter ensures that the climber lands feet first on the crash pad in the event of a fall. You can boulder on natural rocks as well as on artificial walls, and bouldering is a discipline of competitive climbing.

Buildering / building climbing

From sport climbing, especially from bouldering, a new subspecies has meanwhile developed, building climbing . It takes place - often illegally - on facades and architectural monuments. The best-known representative of this type of climbing is the Frenchman Alain Robert , who also usually climbs free solo .

Another type of building is the legal, secured climbing on buildings that have been rededicated as climbing facilities, as is done, for example, at a former air raid shelter in Berlin.

Speed climbing

Speed climbing is about climbing a route in the shortest possible time. This is done both on rock (in free or technical climbing) and on artificial walls (usually in the form of competitions).

Free solo

With the Free Solo ( English for free solo ) all forms of aids and safety devices are dispensed with. A single mistake usually leads to a crash, which is why this type of climbing is often considered the most dangerous and spectacular.

Deep water soloing

Deep-Water-Soloing (DWS), also called Psicobloc, is unsecured climbing over deep water. In the event of a fall, the climber is caught by the water.

Climbing in special terrain

Via ferrata climbing

Via ferratas are climbs or climbing routes that are secured with fixed securing devices such as ladders and steel cables. The climber is connected to the steel cable or ladder by a safety device - the via ferrata set . Depending on the degree of difficulty , contact with the rock is often replaced by artificial steps and ladders. So there are technical aids used to move.

Ice climbing and mixed climbing

Ice climbing is climbing ice formations such as frozen waterfalls and icicles. The climbers use crampons and ice axes (special ice axes) to climb the ice and attach intermediate securing devices in the form of ice screws . Since un-iced (rock) spots can also occur in the approach or along a route, mixed climbing developed as a special form of ice climbing.

Cave climbing

The term cave climbing is colloquially used for moving around a cave and is not a defined climbing style. It can just be walking and slumping . In the same way, simple places can be freely climbed or rope and aluminum ladders are used. Single rope technology is used to drive through shafts .

Rescue climbing

A special form of technical climbing is climbing trained as part of mountain rescue , which requires a well-equipped repertoire of additional technology in order to be able to carry out rescues in addition to self-belaying. Today, the combination of technical climbing access to the accident site and helicopter support is common practice, which requires further specialization in technology.

This topic also includes basic alpine knowledge such as rescuing comrades when climbing in exposed terrain, self-rescue from the crevasse using Prusik technology or basic safety measures for emergency descent , as taught in alpine courses.

Climbing as a professional activity

In order to reach places that are not otherwise accessible, the use of climbing techniques is necessary in some professional fields (workplace positioning) . These developed from technical climbing, but above all from the single rope technique of cave exploration , but today they have an independent repertoire of techniques, methods and materials as well as their own legal basis with regard to safety.

Rope- assisted access techniques are used for cleaning, maintenance and assembly work in inaccessible places such as high - rise facades .

In forestry and tree care, rope-assisted tree climbing techniques are used to care for or fell trees.

In addition, "rescue climbing" has developed into a variant carried out in this civilizational environment; there are now special groups for rescue operations on buildings in rescue services such as the fire brigade and other rescue services. For the rescue guarantee in the commercial area, there are also commercial providers of height rescue .

T5 climbing

A variant of the GPS-supported scavenger hunt geocaching is the T5 climbing caching. The T5 stands for the terrain assessment (terrain 5 of 5). A logbook, similar to a summit book , is stored in a small container (the so-called cache) in a place that is inaccessible without tools. This place must be climbed in order to be able to register. Since a cache can be located in a wide variety of locations, such as mountain peaks, buildings, old power poles, trees, tunnels, etc., a variety of different climbing techniques can be used, some of which have to be combined and adapted to the corresponding requirements. An example of this would be building a cable car to get to a point where you couldn't otherwise secure yourself.

Inspection of routes

When walking a route, it is often not only important whether a route has been climbed, but also how. A distinction is made between the possibilities of climbing a route, based on safety aspects (lead, follow-up, top rope) and sporty (onsight, flash, red dot) aspects.

Lead

→ Main article: Lead climbing

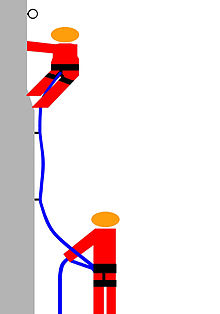

When leading, the climber is secured by the belaying partner from the point at which climbing upwards or to the side began. It is thus secured from below or from the side. At certain intervals the climber attaches the rope to intermediate securing devices . Intermediate securing can either already be in place (rings, hooks ) or must be attached by the lead climber himself ( clamping wedges , friends , knot loops ). In the event of a fall, it then falls below the last intermediate belay until the rope is taut.

- Fall depth = rope elongation + slack rope + 2 × (distance from the last intermediate protection to the fall point).

In principle, the most dangerous situation is when there is no intermediate safety device attached. This can lead to falls with ground contact or, on multi-pitch routes, the maximum fall factor of 2 if the climber falls past the belayer. The "correct fall" can best be trained under professional guidance through practice, that is, conscious falling in safe terrain. The body control that can be achieved in this way significantly reduces the risk of injuring yourself during a fall.

The most harmless are falls in the lead ascent with the intermediate securing in place in heavily overhanging terrain, as there the risk of injuring yourself through contact with the wall is considerably reduced. But here, too, falling has to be learned, as the falling person can often be irritated by the apparently low risk of injury and thus climb / fall less concentrated. In very easy, stepped terrain, if possible, you should not fall at all, as the climber will come into contact with the wall or the ground before the rope is taut.

If the climber falls, a very high amount of energy is generated, which is dissipated by the rope stretching in the rope and by the belayer. Therefore, according to the German Alpine Club (DAV), the climber should have a maximum of 1.3 times the body weight of the belayer, otherwise the belayer experiences excessive acceleration if the climber falls and can lose control of the rope. The acceleration is caused by the tensile force of the rope. It can lead to the climber falling to the ground. If the weight factor (weight difference between climbing partners) is greater, additional measures should be taken to minimize the risk of injury.

Follow-up

→ Main article: Nachstieg

If two people (in "two rope team ") or three people ("three rope team ") are climbing on multi- pitch routes , the first climber climbs first. In Saxon climbing , routes with a pitch are also used in the lead and post ascent. As soon as the lead climber has reached and set up a stand , i.e. a place in the rock suitable for belaying, the other climbers can climb up. From a spatial perspective, the climber who follows is below the belay partner and climbs up to him. In order to save time and a change of location, it is sometimes common for the climber to climb the lead immediately afterwards and set up the next location one pitch above the belay partner.

During the ascent , the rope comes from above, as with top rope climbing. Nevertheless, falls are not always as harmless as with top rope climbing, since in alpine terrain there are often graded terrain or cross passages with a risk of pendulum falls.

Climbing up in climbing gyms or rope courses is unusual because climbing over several pitches is seldom and no special training is required. However, setting up a stand can be practiced here in a way that is easily observable for everyone.

Top rope

→ Main article: Top rope

With top rope climbing, the safety rope runs upwards from the belayer, there through a deflection and back down to the climber. So the safety rope comes from above; hence the English name. If the climber falls while top-rope climbing, he will not fall deep and will be caught gently due to the rope's stretch. The height of the fall is mainly dependent on the length and elasticity of the rope as well as the sag of the rope, known as the slack rope.

After the climber has reached the end of the route (or has no more inclination, time or strength), he sits "on the rope" and is let down by the belayer .

The first time top rope climbing is practiced, how to sit on the rope, close to the ground. For beginners, it often takes a certain amount of effort to let go of the handles with their hands and entrust their weight to the rope. Some find this easier if they hold onto the rope with one hand and only then let go of the handles.

Top rope is often used as a form of safety in climbing gyms or climbing gardens, the risk is considered to be low compared to lead climbing. Almost all climbers have their first climbing experience with top rope belaying. It is also common to climb difficult routes top-rope (i.e. try out the individual climbing moves before climbing the entire route).

Inspection styles

→ Main article: Approach styles

Especially with free climbing, in addition to the sheer difficulty of a route, it is also important to specify the ascent style in which the route was used. Recognized achievements are only those ascents that have been carried out in the red point or a higher-quality style, i.e. in the lead and in free climbing.

Evaluation of routes

→ Main article: Difficulty scales

The difficulties of different climbing routes can be compared by difficulty scales on which the difficulty of the route is rated. There are different levels of difficulty around the world, some of which have developed independently of one another and have different priorities in the assessment. It is therefore often very difficult to compare the individual scales with one another.

Internationally, the French difficulty scale is decisive in free climbing. The scale, which is open to the top, currently includes levels of difficulty from 1 to 9c. From the 2nd to 3rd degree the levels are divided into a, b and c and can be indicated by an additional "+" for a higher level of difficulty. In Germany, the UIAA scale , which is open to the top, is customary for evaluating free climbing routes , which currently ranges from I (easy) to XI + / XII- (grade achieved by a few professionals). The individual grades can still be subdivided with plus (more difficult) and minus (easier). In the east of Germany, especially in Saxon Switzerland and the Zittau Mountains , the Saxon scale written in Roman numerals is common, which is currently up to XII. Degree is enough. A distinction is made between a, b and c from grade VII. In addition to the scales mentioned, there are numerous others. The American, Australian and British scales are currently used more frequently, with the British scale including, in addition to the pure difficulty, a rating for the seriousness , i.e. the danger that occurs in the event of a fall.

As with free climbing, there are difficulty scales for most other forms of climbing. Bouldering problems are marked with the Fontainebleau scale , among other things . In ice climbing, the water-ice scale is mainly used, which mainly shows the steepness of the ice.

Climbing and risk

Climbing is perceived by many as a particularly dangerous occupation, as there are occasional reports of deaths in the media. The presentation of particularly spectacular and risky climbing actions in the media could also have contributed to this assessment. Climbers, on the other hand, are of the opinion that their sport can be practiced very safely through the correct use and improvement of safety techniques.

In fact, the number of serious accidents is small compared to the number of climbers. This applies in particular to sport climbing, which is usually practiced on well-secured routes. In contrast to sport climbing on rock, for which only limited statistical data are available, there are several meaningful statistics on the risk of accidents in indoor climbing, all of which show a low risk of accidents (0.6% accident risk per athlete per year, or 0.016% per climbing day for Injuries of all degrees of severity). The main source of accidents in the rare serious accidents is human error; under normal conditions in the climbing garden and when properly used, rope tears have practically no longer occurred since the introduction of modern kernmantle ropes in the 1960s. Even with the riskiest form of climbing, free-solo climbing , in which a single mistake usually leads to a fatal fall, accidents only occur extremely rarely, as normally only climbers who are really up to the great psychological and technical climbing stresses to take these risks. In addition, the statistics show that most serious accidents do not happen while climbing on the rock, but rather when approaching the rock or at the foot of the mountain / rock, for example due to falling rocks . Nevertheless, climbing, especially climbing in alpine surroundings, like all mountain sports, remains a sport with certain risks. Dangers to life and limb can thereby be reduced, but not excluded.

In order to minimize the risk of an accident, it is advisable to learn the safety technology carefully and to observe the recognized safety rules. Information on this is available from the sections of the various alpine clubs ( German Alpine Club ; Austrian Alpine Club ; Alpine Club South Tyrol ; Swiss Alpine Club ). In addition, since the beginning of 2005, the Austrian Alpine Club and the German Alpine Club have offered the opportunity to have one's belaying and climbing skills confirmed by an examination. Those who pass the exam receive the so-called climbing certificate .

Injuries

A UK study looked at the incidence of climbing injuries:

- 40 percent finger injuries

- 16 percent shoulder injuries

- 12 percent elbow injuries

- 5 percent knee injuries

- 5 percent back injuries

- 4 percent wrist injuries

Calluses, dry skin

Dry and stressed hands are a very uncomfortable problem for climbers. From regular contact with rock and rope, climbers often develop calluses on their hands that can tear open and be very painful. This type of injury is also known as a flapper.

In addition, the magnesia used dries out the hands.

There is a selection of products available for climbers that keep calluses elastic, moisturize the hands, and reduce recovery time.

natural reserve

Since climbing is traditionally practiced in the great outdoors and rocks are often home to fragile ecosystems , the increasing popularity of the sport has led to conflicts between climbers' needs and environmental concerns. Representatives of nature conservation point out that the rocks often form sensitive biotopes and are home to rare plants and animals (especially birds). The environmental aspect should be given priority and the climbers' interest in recreation should take a back seat in case of doubt. In extreme cases, the opinion is expressed that climbing should only be practiced on artificial structures in order to protect nature as much as possible.

Rock-nesting birds such as eagle owls and peregrine falcons are particularly problematic for climbers . Undisturbed rocks or quarries during the breeding season are vital for these species, which can range from February to August until the young become independent. How severe the consequences of unregulated climbing sports in uhu habitats can be in extreme cases is shown by long-term observations by the Society for the Conservation of Owls in the Eifel. In Thuringia , between 1973 and 2015, at least 91 broods were abandoned after disturbances by climbers. In order to solve this problem, numerous temporary closures during the breeding season of rare birds have been agreed by the IG climbing group and other associations. In 2011, the Regensburg biologists Christoph Reisch and Frank Vogler came to the conclusion in a study that climbing had a negative effect on the seed dispersal of rare plants such as the yellow starling flower ( Draba aozides ) and that the genetic variability of the starling flower on climbing rocks was also limited . It was questioned by IG Klettern Basel, as smooth, vegetation-poor zones that have fewer habitat options are per se better suited for climbing than fragile, overgrown areas.

In order to prevent the negative effects of climbing on nature, climbing concepts have been drawn up for most areas by IG Climbing and other clubs , which mostly restrict climbing on a small scale on the basis of voluntary regulations so that consideration is given to plant and animal protection. Many therefore believe that environmental protection and climbing are compatible with relatively few restrictions for climbers. The practice of sport in the great outdoors promotes a bond with nature and an interest in its preservation. When introducing environmental protection measures, one should therefore take into account the interests of climbers. Overall, climbing should be regulated as little as possible, and necessary restrictions (such as blocking rocks) should be reduced to a minimum. In Bavaria, a corresponding procedure for the creation of climbing concepts is contractually regulated between IG Klettern, DAV and the authorities.

The situation in the Federal Republic is currently inconsistent. In many areas, the interest groups of climbers, such as the IG Climbing and the German Alpine Association (DAV), work out compromise solutions in which the preservation of climbing opportunities is taken into account as well as environmental protection. While in some climbing areas almost all rocks have been completely closed - for example in North Rhine-Westphalia - climbing is possible unhindered in other regions. Elsewhere, compromise solutions were found, such as limited time and space climbing bans or voluntary waiver, such as in the Saxon Switzerland, where were developed together with the local National Park Administration climbing strategies for all subareas and climbers also actively participate in protective measures - for example through the surveillance of breeding peregrine falcons at temporarily closed climbing peaks.

In Austria and South Tyrol, climbing is also promoted by the public sector. Tyrol, for example, leads the way, with the quiet area in its own category for protection against excessive tourist use. In Austria and South Tyrol one relies primarily on climbing area management as a local and regional compromise concept between owners, protection authorities and tourism and climbing associations, since with the OeAV, AVS and the other mountain sports associations traditionally active institutions can be found in alpine sports as well as environmental protection.

In the non-Alpine region of Austria, climbing areas have also developed in recent years, which can come into conflict with environmental considerations in scenic protection zones (for example in the Wachau).

Learn to climb

Various organizations (for example alpine clubs or regional climbing clubs) and commercial climbing schools offer courses for almost all types of climbing. There are now extensive climbing halls in which sport climbing and bouldering can be learned and trained. Climbing walls have also been installed at some schools, and climbing is often integrated into the lessons there.

organization

Climbing is a sport that is largely self-organized and, in principle, does not require any regulatory associations. It is not necessary to join a club to practice climbing. (New) sporting or ethical developments (for example free climbing or the outlawing of rock manipulation) are primarily propagated by the climbers themselves.

The umbrella organization for some mountain sports clubs is the Union Internationale des Associations d'Alpinisme (UIAA), while the International Federation of Sport Climbing (IFSC) is responsible for sport climbing and, in particular, for organizing competitions . In addition to the individual sections of the DAV , the climbing interest groups (IG Klettern) are strongly represented in various areas in Germany, which mainly deal with the rehabilitation and development of climbing areas and the nature-friendly design of climbing. The individual interest groups are united under an umbrella organization.

The development of new routes is mostly carried out by local climbers. Until a new route has been successfully climbed, it is called a project. It is common to mark a project as such. After a successful ascent, the first climber gives the route a name and rates the difficulty in order to give the repeaters an idea of the nature of the route. The final level of difficulty usually crystallizes after several ascents by other climbers who check the evaluation proposal of the first climber. New routes are now often published in specialist magazines or on internet climbing sites.

Climbing guides are available to help the climber find their way around the rock.These usually contain sketches of how to get there, directions, any climbing restrictions that may have to be observed, and topos , i.e. sketches of the routes on a rock.

Related topics

Security technology

additional

- Mountain sports

- Rockclimbing

- Rope climbing

- Therapeutic climbing

- List of climbing terms

- List of famous climbers

- List of well-known sport climbers

- List of important climbing routes

literature

- history

- Reinhold Messner : Vertical - 150 years of climbing art , BLV, Munich 2008, ISBN 3-8354-0380-X .

- Security technology

- Pit Schubert : Safety and risk on rock and ice. Three volumes, Bergverlag Rother, Munich 2007-2008, ISBN 3-7633-6016-6 (volume 1), ISBN 3-7633-6018-2 (volume 2), ISBN 3-7633-6031-X (volume 3).

- psychology

- Steff Aellig: About the sense of nonsense: flow experience and well-being as incentives for autotelic activities: an investigation with the experience sampling method (ESM) using the example of rock climbing. Waxmann , Münster / New York, NY / Munich / Berlin 2004, ISBN 978-3-8309-1397-9 (= international university publications , volume 431, also dissertation at the University of Zurich 2003).

Web links

- Link catalog on climbing at curlie.org (formerly DMOZ )

- Climbing wiki

- Climbing: with hooks and eyes. What does physics say about it?

Individual evidence

- ↑ Kurt Albert: Fight Gravity- climbing in Frankenjura, tmms-Verlag, basket 2005, ISBN 3-930650-15-0 ; P. 10

- ^ Steve Long: Safe climbing, Delius-Klasing, Bielefeld 2007, ISBN 978-3-7688-2688-4 ; P. 8

- ↑ Milestones in alpine climbing at www.kletterphoto.de ; Retrieved April 30, 2010

- ^ Andi Hofmann: Better bouldering - basics & expert tips, Tmms-Verlag, Korb 2007, ISBN 3-930650-21-5 ; P. 28 ff

- ↑ Reinhold Messner: Vertical. 100 years of climbing art, Blv, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-405-16420-6 ; P. 86 ff

- ^ A b Stefan Glowacz: On The Rocks, Piper, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-89029-289-5 ; P. 179 ff.

- ↑ Overview of the epochs of climbing on bergfieber.de ( memento of the original from April 30, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. ; Retrieved May 2, 2010

- ^ Andi Hofmann: Better bouldering - basics & expert tips, Tmms-Verlag, Korb 2007, ISBN 3-930650-21-5 ; P. 32 ff.

- ↑ Tillmann Hepp, Wolfgang Güllich, Gerd Heidorn: Faszination Sportklettern, Heyne Verlag, 1992, ISBN 978-3-453-05440-0 ; P. 17

- ↑ Kurt Albert: Fight Gravity- climbing in Frankenjura, tmms-Verlag, basket 2005, ISBN 3-930650-15-0 ; Pp. 72-77

- ↑ History of sport climbing on www.bergleben.de ; Retrieved April 30, 2010

- ↑ Sport climbing is booming! Article on alpenverein.de ; Retrieved May 31, 2010

- ↑ NaturSportInfo on the website of the Federal Agency for Nature Conservation ( Memento of the original from December 5, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. ; Retrieved May 31, 2010

- ↑ Olympic Games Tokyo 2020 . International Federation of Sport Climbing. 2020.

- ↑ Olympic Games postponed to 2021 . Tokyo2020. 2020.

- ^ Michael Hoffmann, Wolfgang Pohl: Alpine curriculum volume 2, BLV, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-405-16182-7 ; Pp. 78-79

- ↑ legal situation in buildering ; Retrieved May 29, 2010

- ↑ Information about the Humboldthain bunker wall on the website of the DAV section Berlin ; Retrieved May 28, 2010

- ↑ compare climbing: rescue technology , Wikibooks

- ↑ Rescue climbers . Video. Production: City of Vienna 2008, flash-video , wien.at TV

- ↑ Lexicon of climbing terms on on-sight.de ; Retrieved May 31, 2010

- ↑ Chris Semmel: DAV Panorama . No. 3/2012 , p. 74, 75 .

- ^ Steve Long: Safe climbing, Delius-Klasing, Bielefeld 2007, ISBN 978-3-7688-2688-4 ; P. 28

- ↑ Tom Duration: The Charm of the Measures ( Memento of the original from November 6, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , in Panorama, Volume 58 No. 4, August / September 2006, ISSN 1437-5923 , p. 18 f .; Retrieved June 3, 2010

- ^ Steve Long: Safe climbing, Delius-Klasing, Bielefeld 2007, ISBN 978-3-7688-2688-4 ; P. 22 f

- ^ Andi Hofmann: Better bouldering - basics & expert tips, Tmms-Verlag, Korb 2007, ISBN 3-930650-21-5 ; P. 19 f.

- ^ Will Gadd: Textbook Ice Climbing: Ice Mixed Drytooling, Panico Alpinverlag, Köngen 2005, ISBN 3-936740-27-5 ; P. 82

- ↑ Ralph Stöhr: A remnant of risk. In: Climbing No. 3/2010, ISSN 1437-7462 , pp. 40–49

- ↑ Indoor climbing - foolproof or error-prone? (PDF; 3.6 MB) on bergundstieg .at; Retrieved May 1, 2010

- ↑ a b Thomas Hochholzer, Volker Schöffl: As far as the hands can reach ... Sport climbing injuries and prophylaxis . 4th edition. Lochner Verlag, Ebenhausen 2007, ISBN 978-3-928026-28-4 , p. 30 .

- ↑ Seilrisse - a summary on bergundstieg.at; Retrieved May 1, 2010

- ↑ The 12 (climbing) commandments - The climbing rules of the Alpine Club, part 1 (PDF; 781 kB), part 2 (PDF; 859 kB); Retrieved May 31, 2010

- ↑ Information about the climbing license on the website of the German Alpine Club ; Retrieved May 31, 2010

- ^ DA Doran, M. Reay: The Science of Rock Climbing and Mountaineering . A collection of scientific articles. Human Kinetics Publishing, 2000, ISBN 0-7360-3106-5 , Injuries and associated training and performance characteristics in recreational rock climbers (English).

- ↑ Creams for climbers tested. In: Climbing Base Hanover. Retrieved February 6, 2015 .

- ^ Michael Hoffmann, Wolfgang Pohl: Alpine curriculum volume 2, BLV, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-405-16182-7 ; P. 114 ff.

- ↑ Karlfried Hepp, Friedrich Schilling, Peter Wegner: Protection of the Peregrine Falcon , 1995, Beih. Publ. Nature conservation u. Landscape maintenance Bad.-Württ. 82, ISSN 0342-6858

- ↑ Joint declaration on climbing and nature conservation by DAV and NABU (PDF; 313 kB); Retrieved May 2, 2010

- ^ W. Breuer & S. Brücher: Dangerous medium-voltage masts and climbing: Current aspects of Uhuschutzes Bubo bubo in the Eifel. Charadrius 46 (1-2) 2010, pp. 49-55.

- ↑ Martin Görner 2015: On the ecology of the eagle owl (Bubo bubo) in Thuringia: A long-term study. Acta ornithoecologica Vol. 8, H. 3-4, p. 162.

- ↑ Climbing has negative consequences for rare plants

- ↑ Frank Vogler, Christoph Reisch: Genetic variation on the rocks - the impact of climbing on the population ecology of a typical cliff plant Journal of Applied Ecology, 2011 Volume 48, Issue 4, pages 899–905, doi: 10.1111 / j.1365 -2664.2011.01992.x .

- ↑ Statement by IG Klettern Basel ( Memento of the original from November 4, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Federal Association of IG Climbing ( Memento of the original from November 1, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b Lecture by Winfried Hermann, Chairman of the Sports and Nature Board of Trustees ( memento of the original from October 25, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. ; Retrieved May 1, 2010

- ^ Stefan Winter: Richtig Sportklettern, BLV, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-405-16074-X ; Pp. 114-115

- ↑ Alienation of young people from nature through climbing bans . Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- ↑ Framework Agreement Bavaria ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 31 kB)

- ↑ Strategies for solving the conflict between climbing and nature conservation by the IG Climbing and Nature Conservation in Rhein-Main eV . Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- ↑ Climbing conception Allgäu ( Memento of the original from December 21, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . Retrieved June 5, 2010.

- ↑ Overview of the NRW climbing areas . Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- ↑ Nature and environmental protection in the Saxon Mountaineering Association ( Memento of the original from April 13, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- ↑ Climbers Paradise Tirol ( Memento of the original from July 19, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed July 5, 2010

- ^ Oesterreichischer Alpenverein, sport climbing in Innsbruck

- ↑ See focus on protected areas - a challenge for the Alpine Club . In: Alpine Club . 4 · 05 (Sept.-Oct.), Year 60 (139). OeAV, Innsbruck 2005, p. 8-15 .

- ↑ Information on climbing in schools at the Bavarian State Association ( Memento of the original from April 10, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. ; Retrieved May 11, 2010

- ^ Official website of the UIAA ; Retrieved May 11, 2010

- ↑ Official website of the IFSC ; Retrieved May 11, 2010