Lyon Metro

| Basic data | |

| Country | France |

|---|---|

| city | Lyon |

| Transport network | SYTRAL |

| opening | April 28, 1978 |

| Lines | 4th |

| Route length | 32.1 km |

| Stations | 44 |

| use | |

| Passengers | 740,000 per day (2013) |

| vehicles |

MPL 75 , MCL 80 , MPL 85 (manufacturer: Alsthom ) |

| operator | Keolis Lyon |

| Power system |

750 V = over the side busbar (lines A, B, D) and overhead line (line C) |

The Métro Lyon , brand name TCL Métro , is the metro in the city of Lyon in eastern France . With a route length of 32.1 kilometers and 44 stations, it is the third largest metro in France after Paris and Lille . In terms of passenger volume, it ranks second behind Paris with around 742,000 passengers per day (2012). With a share of around 50 percent of passenger movements in public transport, it is also by far the most important public transport in the city.

The Métro has numerous operational and technical features. These include continuous left-hand traffic , a rack section , trains with rubber tires, a vehicle profile that is unusually wide by French standards, and computer-aided and partially driverless operation.

Most of the route network was put into operation between 1978 and 1992. The originally planned further route expansion was largely abandoned for demographic and financial reasons in favor of the tram, which was reintroduced in 2000 . In general, the Métro did not do justice to its originally intended role of significantly accompanying urban development in the greater Lyon area to the extent desired.

Historically, the construction of the Métro Lyon was for a long time "a kind of symbol" for the constant political disputes between the local municipal administration and the central government in Paris, which the local population looks back with a certain pride.

Organization and finance

The Métro is operated by Keolis Lyon together with most of the other public transport systems in the region under the brand name TCL, which is advertised as Transports en Commun de l'agglomération de Lyon . The client is the regional transport association SYTRAL (Syndicat mixte des Transports pour le Rhône et l'Agglomération Lyonnaise).

SYTRAL is the owner of all operating systems and vehicles, carries out offer and tariff planning as well as quality assurance and is also responsible for financing. The traffic performance is put out to tender every six years. The last time this happened was on January 1, 2011, when Keolis Lyon, a subsidiary of the French Keolis group, was awarded the contract.

The name TCL goes back to the former private tram and bus operator Lyons, the Société des Transports en Commun Lyonnais (Société TCL), whose naming rights today's SYTRAL took over in 1976.

There is no precise information about the operating costs of the Métro. In 2012, SYTRAL spent 377.6 million euros on the operation of the entire network, of which Métro certainly made a noticeable contribution. In contrast, the costs for the wear-related procurement of property, plant and equipment were low at 2.7 million euros in relation to investments of over 201.1 million euros in the overall network. The most important source of income is the local traffic tax ( versement transport ) with a total revenue of EUR 260.1 million, followed by fare income of EUR 199.5 million and EUR 127.1 million in levies from the associated municipalities. The Rhône department and the central government, on the other hand, make only minor payments.

Route network

Expansion and operation

The extent of the metro network essentially corresponds to the inner, most densely built-up areas of the metropolitan area of Métropole de Lyon . These extend from the historic city center, which lies above the mouth of the Saône , which has been dragged four kilometers to the south into the Rhone, on the peninsula ( Presqu'île ), mainly to the east and south-east. In the north and west, on the other hand, where steep mountain slopes have largely prevented greater settlement activity in the vicinity of the city center, comparatively few kilometers are recorded. However, the network is in some cases quite significantly behind the extent of the closed development.

Apart from the urban area of Lyons, the Métro serves the La Croix-Rousse district above the city and the suburbs of Caluire-et-Cuire , Villeurbanne and Vaulx-en-Velin in the east, and Vénissieux in the southeast. In addition to the historic city center, the centrally located Part-Dieu site on the east side of the Rhone is of particular importance for the metro network . This includes a very large shopping center, various office complexes and the most important inner-city train station for TGV long-distance transport and thus represents a kind of second city center for Lyon.

The metro network consists of four lines with a total length of 32.1 kilometers and 44 stations, crossing stations counted twice. All four routes are served by one line each. These are designated with the letters A to D and have individual identification colors. Lines A, B and D cross each other in pairs in the city center and thus form a secant network . On line C, you can only change to line A at the Hôtel de Ville-Louis Pradel station on the northern edge of the peninsula.

Lines A, B and D use the same drive technology and are accordingly connected to one another via operating lines. The trains run on rubber tires ( Métro sur pneumatiques ) and are supplied with traction current by means of a busbar painted on the side . In contrast to lines A and B, line D has fully automatic and unmanned operation.

In contrast, line C is designed as a conventional friction track and in sections as a cogwheel track according to the von Roll system. The trains run on steel wheels and draw their power from an overhead contact line .

The route network is operated entirely in left-hand traffic and runs almost exclusively underground. Only the depots and their entrances and two sections of line C are laid out above ground. This is where the network's only two above-ground stations, Croix-Paquet and Cuire, are located.

The trains run daily between 5 a.m. and midnight, every 2 to 11 minutes, depending on the time of day and the line. On May 1st, Labor Day , operations will be completely shut down. During the relatively frequent strikes in the public service in France, operations on lines A, B and C are restricted or completely stopped, while line D operates without impairment, as it cannot be strikes due to a lack of drivers. In this context, lines A and B should also be converted to fully automatic and unmanned operation by 2017/18; this has now happened on line B.

Line A

Line A begins at the Lyon-Perrache long-distance train station on the southern edge of the old town on the peninsula. From there it runs under the central pedestrian zone in a northerly direction to the city hall (Hôtel de Ville) at the north end of the peninsula. There it turns in an easterly direction, crosses the Rhone in the tube of the Morand Bridge and then runs under the Cours Vitton and the Cours Émile Zola further east to the terminus Vaulx-en-Velin La Soie. This is about one kilometer behind the eastern ring road on the municipal boundary between Villeurbanne and Vaulx-en-Velin. Right next to it is the associated workshop, the Ateliers de la Poudrette .

Métro A is 9.2 kilometers long, has 14 stations and in 2012 averaged around 248,000 travelers per day. The line identification color is red. On Line A, three-car trains are used. The platforms are designed for a train length of four cars.

Line B

Line B starts at a side platform in the Charpennes-Charles Hernu underground station on line A, which is about a third of the way from Hôtel de Ville to Vaulx-en-Velin and on the border between Lyon and Villeurbanne. From there, the route runs east parallel to the Rhone to the Stade Gerland , about one kilometer southwest of the Saône estuary. In the further course, the tunnel crosses under the Rhone in a long curve and flows into the terminal station Oullins Gare in the suburb of the same name .

Line B initially serves the Part-Dieu site with the station of the same name. This is followed by the Saxe-Gambetta subway station, which serves as a junction with line D, and the Jean Macé station, where a transfer station for suburban traffic to the south and south-east has existed since 2009. In particular, line B is the only metro line that opens up the Part-Dieu site, so you have to change trains in this direction from three of the four metro lines at least once.

Métro B is 8 kilometers long, has ten stations and counted around 158,000 travelers per day (2012). Their line identification color is blue. The same three-car trains are used on line B as on line A. The platforms here allow four-car trains.

The Poudrette workshop is responsible for line B as well as for line A. The trains can use a connecting curve at the Charpennes-Charles Hernu station to go beyond the end of the platform and then head east onto the line A tracks.

Line C

Line C was created between the stations Croix-Paquet and Croix-Rousse on the route of a funicular that opened on April 12, 1891 and operated until July 2, 1972 . It heads north from the Hôtel de Ville station to the high plateau of Croix-Rousse to Cuire, the southern district of Caluire-et-Cuire . The southern section between the stations of Hôtel de Ville and Croix-Rousse has a steep gradient of 17.3% to the north, which is why line C was opened on December 9, 1974 as a rack railway. This makes this section the steepest underground line in the world after the Carmelite in Haifa . Line C also combines the only two above-ground sections of the network. Both go back to former railway lines that were used to route the Métro. In particular, in the area of its northern terminus, line C uses the route of the former Lyon-Croix-Rousse-Trévoux line .

Initially, the two electric railcars MC1 and MC2, multi- traction vehicles built by Stadler with electrical equipment from BBC, were sufficient for operation . On May 2, 1978, the line was extended down the valley to the new terminus Hôtel de Ville, which is the transfer station to Métrolinie A. Therefore, the MC3 railcar was subsequently procured in 1978, but it could only run individually. At the beginning of the 1980s, the line that had previously ended in Croix Rousse was extended by 800 m to the Hénon station. The tunnel was built using the cut-and-cover method. To the north of the provisional terminus, there was an above-ground operating line to the Ateliers de Hénon workshop, 500 m away , which is now used in regular service to the current terminus in Cuire.

In the course of the last extension, the ten-year-old railcars were parked and replaced by five new MCL 80 vehicles . These double railcars offer more space, and their car bodies are optically matched to those of the other metro trains. However, power is supplied via an overhead line , which is why each car body has a pantograph . The MC3 railcar from 1978 is on display in the outdoor area of the Mulhouse Railway Museum (Cité du Train).

Métro C is 2.4 kilometers long and has five stations. It is the shortest of the four lines. With 34,700 travelers per day (2012) it is also by far the least frequented. Therefore, only two-car trains are used on correspondingly short platforms. On the other hand, with these numbers of passengers, Line C is probably the most frequented cog railway in the world.

Due to the island operation, Line C has its own workshop. The line identification color of line C is yellow.

Line D

Line D begins in Vaise, a suburban train station on the railway line towards Paris in the far north-west of Lyon. It then crosses the 9th arrondissement south to Gorge de Loup station, from where the suburban trains in the direction of L'Arbresle run. From there, the tunnel runs in a south-easterly direction under the Fourvière hill through to the Vieux Lyon-Cathédrale St. Jean station, directly on the western bank of the Saône. There is an integrated transfer station to the two funiculars that lead up to the Fourvière hill, the Saint-Jean – Saint-Just cog railway and the Funiculaire de Fourvière . The route then crosses under both rivers, crossing line A on the peninsula about halfway between Perrache and Hôtel de Ville at Bellecour station. On the east side of the Rhone it runs under the Cours Gambetta and the Rue Guillaume Paradin further to the south-east. Then it turns south and continues under Boulevard Pinel and Avenue Jules Guesde to the terminus Gare de Vénissieux on the railway line to Grenoble . The last two stations are in the municipality of Vénissieux.

Line D is 12.6 kilometers long and has 15 stations, the longest of the four lines and the busiest with 302,000 passengers per day (2012). Although the platforms are designed for four cars just like on lines A and B, only two-car trains run on line D. But the clock is much closer than on the other two lines. The line identification color of line D is green.

Although there is a connecting curve to line B at the Saxe-Gambetta station and thus indirectly a path to Poudrette, line D has its own workshop, the Ateliers du Thioley . It is located about one kilometer north of the Gare de Vénissieux station and was originally only planned as a pure depot without workshops. Because the logistical effort to lock the trains to Poudrette across lines B and A had proven to be too great, the plans were changed during the construction of line D according to the current status.

Supplement with trams, trolleybuses and buses

The metro network is supplemented by the local tram and a close-knit trolleybus and bus network . The tram, together with a few selected bus lines (lignes fortes), serves important tangential connections in the city that the Métro cannot establish or only by changing, especially in the direction of Part-Dieu. In addition, many of these lines “extend” the metro in the outskirts to the suburban settlements, which the metro did not reach in many places.

The most important transfer points to the metro network in the city center are Perrache, Bellecour, Hôtel de Ville and Part-Dieu. In the outskirts, Laurent Bonnevay-Astroballe on line A for the trolleybus to Vaulx-en-Velin, Cuire for the trolleybus to Caluire and Charpennes-Charles Hernu for the settlement area north of line A. Gare Vaise and Gorge de Loup in the northwest and Grange Blanche and Gare de Vénissieux in the southeast.

Construction work

Tunneling

The route network of the Métro Lyon runs - apart from the exceptions mentioned - in tunnels. Some exposed sections near or above the ground level are enclosed, such as the Rhone crossing of Line A in the tube of the Morand Bridge and the essentially above-ground turning system behind the Vaulx-en-Velin station, which is hidden in a long, windowless concrete structure.

Sub-paving

Contrary to the French conventions prevailing to date, the majority of tunnels and platform systems are located in a simple, low-lying area ( sub- paved railway ). The tunnel floor is normally around four to five meters below street level. Exceptions to this rule are the necessarily multi-storey crossing stations between the lines as well as individual stations, which made it necessary to build intermediate distribution levels due to the high number of passengers or topographical reasons . At the time, it was designed as an under-paving tramway, in particular in contrast to the then only Métro in France, the Métro Paris . There the train runs in the second low level, while the first low level only serves as a distribution level.

Apart from basic economic considerations, the geological conditions in particular played an important role. The area around the confluence of the Rhone and Saône rivers lies in a sedimentary basin that has been filled in for millions of years by erosion from the western Alps . Apart from the granite hills in the north and west, the city stands practically on a huge, water-permeable gravel bank made of loose rubble , through which the groundwater flows from a few meters depth due to the close proximity to the rivers and the flat topography . Structures that go deeper than the aforementioned four to five meters underground must therefore be sealed against the ingress of water and secured against floating at great expense. If used on a large scale, this would have exceeded the budget for the Métro. Tunnel construction at great depths, such as in Moscow, was not possible because there are no watertight layers of rock beneath the rubble in Lyon.

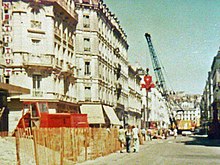

The tunnels were mainly built using the conventional open construction method. For this purpose, a building pit secured with sheet pile walls was dug, the base was sealed against the ingress of groundwater as far as necessary, the tunnel was built and the pit was then backfilled. In contrast to this, the roof-top construction was used at particularly heavily frequented intersections in order to be able to make the surface available to traffic again as quickly as possible.

Shield drive

An important exception are the two tunnels under the rivers along lines B and D, which were excavated using shield driving . In particular, the first crossing of the two rivers in the city center during the construction of Line D in the mid-1980s posed a technical challenge. Here it was necessary to build a longer tunnel in the loosely settled soil below the water table. Because an above-ground route over the two nearby bridges similar to line A was ruled out from the start because it would have had to give up an important inner-city road tunnel under the Quai Jules-Courmont directly on the west bank of the Rhône.

On the other hand, the tunneling methods established at the time reached their limits at this point. The construction of an immersed tunnel was not possible, on the one hand because of the curvy lines and on the other hand because of the complicated flow conditions that mountain rivers naturally bring with them. On the other hand, the three nearby junction stations, Vieux Lyon, Bellecour and Saxe-Gambetta, did not allow tunnels to be routed in any depth below groundwater.

A variant of the classic shield tunneling, newly developed by the German construction company Hochtief at the time, was used . This made it possible to pass under the two rivers at a close distance and with only a few meters of cover to the river bed and under groundwater. There was a bentonitumspülten plate, between the tail and a downstream, actionable inner formwork steel fiber reinforced Extrudierbeton was introduced. Both the bentonite and the extruded concrete were under overpressure in order to prevent the ingress of groundwater and subsidence on the foundations of houses above.

The same procedure was used again for the second underground river crossing on Line B between Gerland and Oullins. In contrast to the first tunnel with two single-track tubes, only one double-track tube with a correspondingly larger diameter was drilled here for cost reasons. In addition, the machine had unlike the line D in addition to sound - and penetrate granite containing layers, including two different sets drill teeth were required (Mixschildtechnik).

The Morand Bridge

Because the procedure described for building tunnels below the groundwater level was not yet available when the first Rhone crossing on Line A was built, another solution had to be found at this point. Together with the aforementioned Métroline line between Place Tolozan and Place du Maréchal Lyautey, today's Morand Bridge was created, a two-story bridge that was to accommodate road traffic on the upper level and the subway on the lower level. It is a reinforced concrete box girder bridge with two parallel boxes, each of which has a metro track running through its cavities. The bridge stands out from the other road bridges in the city center thanks to its modern shape and - due to the second level below the carriageway - its unusually high profile.

Train stations

Most stations have two opposite side platforms on non-pivoted tracks. The platforms are around three meters wide and 70 meters long, so that they can accommodate four-car trains. The stations are usually between 600 and 750 meters apart and are structurally prepared so that they can be extended to 110 meters for six-car trains. Like the tunnels, the stations are usually located in a simple lower position directly below the road surface.

The platforms can be reached via fixed stairs and, with a few exceptions, also via elevators . Escalators are mainly reserved for stations at greater depths and transfer stations. The exits are either at the ends in line with the platforms or in the middle of the platforms directly behind the waiting area and lead directly to the sidewalk on the side. Thus, usually only one platform can be reached from each side of the street, and - due to the left-hand traffic - always the one belonging to the trains in the opposite direction of the traffic.

In terms of the architectural design of the stations, a distinction can be made between two epochs. The first covers the period between the Métro opening in 1978 and around 1985, the second relates to all station buildings that were put into operation later, as can be found primarily along line D.

The stations from the first epoch are compact, simple, contemporary, functional and relatively dark in design. They consistently have relatively low storey heights. The ceilings are painted black. Above the platforms, white slats are hung across the direction of travel, while the track area is kept distinctly dark. The walls are covered with tiles or panels in contemporary, muted colors. The platform is only finely paved ; Safety strips and the door positions are marked by a plaster guidance system for the blind . The arrangement of the ceiling lighting emphasizes the edge of the platform; Uniformly shaped single seats made of hard plastic are attached along the longitudinal walls.

With the stations from the second epoch, on the other hand, great importance was attached to aesthetics in addition to the functional design . The stations are designed much more individually and, in contrast to the previous buildings, should reflect the peculiarities of the respective city districts. They often have significantly higher room heights and relatively often have intermediate levels. Inside, earth tones and contemporary light browns and gray tones predominate. The platforms are not paved, but tiled. Some stations have side windows or skylights so that daylight can enter. In some places, lighting has been experimented with, such as a glowing platform floor or ornate ceiling lamps. The stations are integrated into their urban environment through reception pavilions or open entrances in the area.

Some stations have works of art:

- Bellecour: Le Soleil, Ivan Avoscan ;

- Hotel de Ville - Louis Pradel: La Danse, Josef Ciesla; Les Robots, Alain Dettinger;

- Charpennes - Charles Hernu: Le Signal, Alain Lovato ;

- Gratte-ciel: Les Binettes, Armand Avril ;

- Part-Dieu: Mosaïque, Jean Piton;

- Place Guichard: Vitraux, René-Maria Burlet ;

- Saxe - Gambetta: Sculpture en acier, Jacques Bouget;

- Place Jean Jaurès: Rive de la planète, Rive de l'écrit, Patrick Raynaud ;

- Debourg: La forêt souterraine, Bruno Yvonnet;

- Stade de Gerland: Le Roc-aux-Sorciers, Jean-Luc Moulène ;

- Hénon: Panneaux de mosaïque et fragments de fresques gallo-romaines, Claude Cognet;

- Gare de Vaise: Complément d'image, Victor Bosch ;

- Valmy: installation, Jean-Philippe Aubanel ;

- Vieux Lyon - Cathédrale Saint-Jean: In Aeternum Renatus, Geormillet;

- Grange Blanche: Lyonéon, Nicolas Schöffer ;

- Parilly: Ciel polychrome, Patrice Giorda .

Industrial engineering

Operations center

All four metro lines are controlled and monitored independently of the operating technology in the operations center (poste de commandes centralisées, PCC). This is located next to the Part-Dieu underground station on line B below the shopping arcade there. From there, the train operation is controlled centrally by a route computer ( train control ). For this purpose he is working from the digitally stored schedule by monitoring the track sections and connected routes signal boxes along the metro lines, the routes established, locates the trains along the route and the actual state compares with stored reference values. The associated information is presented to the dispatcher on screen workstations, from where action can be taken in the event of a malfunction ( Automatic Train Supervision , ATS).

In addition, all technical equipment of the Métro such as access systems, elevators and escalators, energy supply and dynamic passenger information are controlled and monitored from the operations center. The television images from the surveillance cameras and the lines from the emergency and alarm systems in the subway stations converge there. Some of this data is also made available on the World Wide Web so that passengers can call up information on operational disruptions and the status of elevators and escalators in real time via the Internet. In the same way, the timetable is made available both route-related and for individual travel requests via a database.

The original equipment of the PCC came from Alsthom . Since then, it has been changed several times with increasing technical progress. Most of the systems currently in use (2013) come from GTIE Transport, a subsidiary of the French Vinci group.

While all four metro lines are controlled equally via the operations center, several different types of train control and automation are used from line to line. The technical components used differ accordingly.

Computer-aided operation on lines A and B.

The computer-aided operation (pilotage automatique, PA) on lines A and B is implemented as punctual train control (PZB) with semi-automatic train routing and automatic keeper recognition ( Automatic Train Operation , ATO, gradation STO). The central computer not only directs and protects trains, but also automatically accelerates and brakes the vehicles . The trains do not run completely independently, but are still handled and monitored by the train driver.

The train is routed using digital travel commands in the form of target speeds that are continuously sent to the vehicles by the route computer. For this purpose, the route is divided into blocks, which are provided with cable line conductors for signal transmission . These build up an electromagnetic field between the rails along the route, which is scanned and evaluated by receiving antennas on the traction vehicle. Different speeds are represented using different frequencies. The system indicates a stop, for example at a train station, over several short sections with decreasing speed levels. The locating of the trains takes place in the same way via a return channel.

In order to enable the transfer of the travel commands and the localization, the train driver must correctly set the line and course number on the vehicle when leaving the depot. The train number consists of the line code letter followed by a two-digit number and can be read on the outside of the vehicle on a display on the upper edge of the windscreen.

The PA knows a total of five operating modes. In addition to the normal, computer-aided automatic mode, there are three different auxiliary modes for different types of malfunctions as well as another computer-aided, manual mode (manual mode), which is used to train the driving staff and which must be completed on a regular basis.

Despite the computer-aided operation, conventional, automatically operating block signals are also installed along lines A and B , which are not connected to the operations center. This means that in the event of a malfunction, it is possible to drive entirely without the aid of the route computer. For manual operation, additional light signals are also installed, which visually transmit movement commands to the train driver by means of illuminated letters.

Train control on line C

As with lines A and B, the train protection on line C is designed as an automatic, punctiform train control. Here, block-by-block, continuous conductor loops are used, which are laid between the rails and in which the speed profile of the respective block is stored. This system is in turn supplemented by block signals, the block-by-block train location via a return channel using train numbers and light signals for the transmission of travel commands.

However, there are significant differences compared to the other two lines. A different technical system is used on Line C with the Siemens PA 135, and above all the trains are driven exclusively by hand and without automatic drive and brake control. Automation of line C is not possible because of the rack section and the associated technical features of the vehicle.

Fully automatic operation on line D.

The fully automatic operation (pilotage automatique intégral, PAI) on Line D is designed as a line train control with fully automatic and unmanned train control (Automatic Train Operation, ATO, gradation UTO). This is where train routing, train protection and all of the regular train operations, including departure and return journeys to and from the depot, are fully automated. The associated technical system is called Siemens Trainguard MT CBTC and was successfully used here for the first time worldwide in the course of the opening of Line D in 1992.

The train protection is fundamentally different from the other three lines. The route is not divided into blocks , but the trains run in a changing spatial distance on an electronic view. The vehicles determine their location automatically and report it quasi-continuously to the following train via the route equipment. This in turn calculates the point from which he has to reduce his speed, taking into account his own location and braking distance. Each train has two redundant microprocessors to calculate this braking point . These must always come to the same result in the calculation (two-out-of-two system), otherwise the train stops immediately.

In addition, compared to the other three metro lines, additional safety-related components are required for unmanned operation on both the track and the vehicle side, which take on the duties of the train driver. The stations are equipped with a horizontal light barrier carpet below the platform edge, which detects objects and people who have come into the track area. This system is supplemented by surveillance cameras at the stations, the images of which are transmitted to the control center, as well as alarm-secured doors at the platform ends, which are intended to prevent unauthorized entry into the tunnel. The on-board safety devices include, for example, lane evacuators , anti- trap devices on the doors and systems for train completeness checks .

The system described, which is historically known under the name MAGGALY, Métro automatique à grand gabarit de l'agglomération lyonnaise (German: automatic metro with a wide profile in the greater Lyon area) differs in essential aspects from the VAL - also known from France - Metros. With the MAGGALY there are no platform screen doors that would prevent people or objects from getting into the track area. Instead, the complex systems mentioned above are used for track monitoring . In contrast to the VAL, the train is not influenced by movement commands that are continuously transmitted by a central computer, but by the trains themselves. With the MAGGALY, the central computer is essentially only used for routing the train and for monitoring the system itself.

Rolling stock

There are currently (2013) three different vehicle types in use at Métro Lyon. Depending on the drive technology, they are referred to differently as MPL 75, MCL 80 and MPL 85. M stands for Métro, P for Pneus ( French pneu "tire" ), C for Crémaillère ( French crémaillère "rack" ) and L for Lyon. The following two digits indicate the year of manufacture of the associated prototype.

The vehicle superstructures are all from Alsthom . They are derived from a single design and are therefore very similar to each other. The car bodies are always a good 17 meters long and made of a self-supporting aluminum construction. They have three double pivoting sliding doors on each side, strikingly large front windows and large, deep side windows with rounded corners. The end pieces of the car body with the end walls are made of fiberglass composite . At 2.89 meters, the vehicles are much wider and therefore more spacious than in all other French Métros and were very modern in design at the time.

MPL 75

The MPL 75 vehicle is used on lines A and B. It was procured in two deliveries for a total of 32 units between 1978 and 1981 and is designed for computer-aided operation as standard.

The MPL 75 consists of three parts as standard, namely two railcars, each with a driver's cab at the outer end and one, theoretically several, non-motorized trailers as an intermediate car. The vehicles are closely coupled to one another ; there are Scharfenberg couplings at the outer ends of the train . The trains do not allow multiple traction . The hourly output is 868 kW, the design-related top speed 90 km / h.

As a Métro sur pneumatiques , the MPL 75 runs on rubber tires. Horizontally arranged wheels, which are supported on the busbars, serve to guide the train sideways. Internal steel auxiliary wheels are used for lateral guidance on points and take over an emergency function in the event of tire damage. The pantographs are located in the middle of the powered bogies and coat the busbar from the inside. Other technical features of the train are air-sprung bogies , thyristor control and recuperation brakes as well as hydraulically operated shoe brakes on the auxiliary wheels.

The original color of the trains was a contemporary, bright orange-red called corail ( French corail "coral red" ). The trains were given their current (2013) color scheme with a white car body and light gray doors between 1997 and 2002. In addition, the original transverse seats in the interior were replaced by longitudinal seats between 2011 and 2013, so that compared to the original furniture there was a little less seating and a lot more Standing space is available.

MCL 80

Type MCL 80 is used on line C. It is most similar to the MPL 75 because the car bodies are basically identical, with the exception of the pantograph and the braking resistors on the roof. However, the MCL 80 only exists as a double multiple unit without additional trailers, because line C only has two-car trains. The total of five trains were delivered at the end of 1984 and, like the MPL 75, were originally painted orange-red. They were given their current white color scheme between 2005 and 2008.

In contrast to the car body, the drive technology of the MCL 80 differs fundamentally from the MPL 75. According to the route on line C, the vehicles have a mixed drive, which is designed both for operation as a conventional friction railway and as a rack and pinion railway. The manufacturer is the Swiss company SLM Winterthur .

The vehicles roll on railway wheels . Each bogie is driven by a direct current motor via a change gear on the respective valley-side axis of the bogie, on each of which a drive gear is seated. The axis formula is therefore A1'A1 '+ A1'A1' when viewed from the valley side. The design-related maximum speed is 35 or 80 km / h, depending on the operating mode.

According to its drive technology, the MCL 80 has several independent brake systems. A regenerative resistance brake, which enables the braking energy to be fed back into the overhead line, is initially used as the service brake. In addition, hydraulically operated shoe brakes act on the running surfaces of the wheels for operation as an adhesive web. In contrast, two hydraulic spring-loaded brakes are installed for operation as a rack railway ; one is designed as a gear brake with brake drums on the drive axles, and the other as a ratchet brake to prevent reverse travel when driving uphill.

The complex technology of the MCL 80 resulted in a very high purchase price. A double multiple unit cost around 42 million FF in 1984 (2013: 11.8 million euros) and thus almost 2½ times as much as a complete MPL 75 train.

MPL 85

Type MPL 85 is used on Line D. From 1985 to 1991, 72 cars from this series were purchased together with the prototype, which are coupled to a total of 36 double railcars. Again, the same car body was used as in the MPL 75, this time with slightly different front sides. The bogies are basically identical, but have different drive motors and a different axle formula. The continuous output of 512 kW and the design-related top speed of 75 km / h are lower than with the MPL 75. For this, some technical improvements have been made, such as disc brakes instead of the shoe brakes.

The MPL 85 was designed for unmanned operation right from the start. The passenger compartment extends the full length of the car and an additional row of seats is installed instead of the driver's cab. However, the trains have a makeshift driver's cab for manual operation, which is located in a concealed console that is mounted in the middle of a cross bracket directly on the windshield.

Like the MPL 75, the MPL 85 was converted from transverse to longitudinal seats to increase the transport capacity. This happened in the years 2008 to 2010. However, the car bodies have not yet been repainted, but kept their original, orange-red color.

"Avenir Métro 2020" program

This program is intended to increase the capacity of lines A, B and D of Métro Lyon in order to be able to cope with the increase in passenger numbers expected in the coming years. In this context, the operator placed a firm order with Alstom for 30 metro trains in autumn 2016 . There is also an option to deliver 18 more trains. The first four trains are to be delivered in the course of 2019. They are intended for line B.

The trains will be 36 m long and can accommodate up to 325 passengers. They are designed so that 96% of the components can be recycled. By improving the energy recuperation during braking and the use of LED lights, energy consumption should be reduced by 25% compared to the vehicles currently in use.

story

Early planning

The first considerations for building an underground railway in Lyon came up around the turn of the century, i.e. at the time when the construction of such railways began in the major cities of the western world. In this way, between 1900 and the end of the Second World War , several different proposals for underground railway lines in the urban area appeared every ten years. All of these were not pursued any further and were forgotten again.

Standstill after the Second World War

In the post-war years, there was no great progress on the subject of Métro. It is true that the urban public transport, which had been privately financed to date, was nationalized when the concession expired in 1941, so that planning sovereignty passed to the public sector. However, the essential financial and planning competencies for setting up a means of mass transport were not at the local level in the sense of local self-government , but with the central government in Paris and its subordinate authorities. The state control of the French economy exercised there in the form of multi-year plans in the post-war years was primarily geared towards the development and modernization of certain branches of industry and hardly concerned with inner-city transport networks. In particular, local public transport, like the province as a whole, was neglected due to certain national political decisions. In addition, several studies, especially in Lyon, initially assessed the geological and financial prerequisites for the construction of an inner-city rapid transit system as negative.

In contrast, with the economic prosperity of the post-war years in Lyon, as in all French metropolitan areas, the population and employment and the associated traffic problems grew. Between 1954 and 1962, the population in Greater Lyon rose by over 100,000 and approached the million mark; the number of motor vehicles had doubled between 1954 and 1959 alone. During this time, the transport network was by no means able to grow to the same extent. The comparatively very high population density and the natural lack of space in the area of the core city further exacerbated the problem. Added to this were the prefabricated prefabricated districts on the edge of the settlement area, which had been created since the 1960s and had no efficient transport links from the start.

The way to the first metro

Organization of the metro construction

In May 1963, the Association Lyon-Métro formed an interest group for the first time . In contrast to the previous drafts, this succeeded for the first time in convincing local politicians seriously of the usefulness and necessity of such a project through lobbying and thorough investigations. So in 1966 - still with the help of the Paris Transport Authority (RATP) - the official project study was created, the preliminary design in 1969 and finally the complete detailed planning for the first construction phase in 1970.

In order to prevent any conflicts of interest between the central government, the department and the municipalities, a project company, the Société d'Études du Métropolitain de l'Agglomération Lyonnaise (SEMALY) , was set up to plan and build the Métro . This acted as an employer for the engineers involved as well as a builder and financier. As was customary in France, the financial resources came from a loan from the central state pension fund .

The outsourcing of the metro project to its own special purpose vehicle, which is independent of Paris, was unique in France and gave those involved a relatively large amount of leeway for decision-making. This fact is responsible for many of the operational and technical peculiarities of Métro Lyon, such as left-hand traffic, the train's profile width of 2.89 m, which is unique in France, or the control of the metro from a central computer. In particular, the endeavors of the central state pension fund such as the RATP to achieve planning sovereignty over the project could be circumvented by means of “a certain complicity”. This was important insofar as the RATP, as the only operator of urban rapid transit systems in France at the time, claimed a certain “national sovereignty” in this area and maintained excellent relationships with the responsible ministries.

This made it possible, for example, to set the profile width of the trains to 2.89 m and thus well beyond the French "Métro-Gardemaßes" of 2.5–2.6 m, that of the Métro Paris in all others due to political pressure newly built French Métros of the post-war period came into use. The background for this insistence on a wagon profile that is unusually narrow by international standards was fears at the national level that foreign wagon builders could penetrate the French market with their usually wider series vehicles if they found suitably wide metro tunnels.

Definition of the lines

The choice of the route of the Métro proved to be difficult in Lyon due to the urban structure. Initially, everyone involved agreed that the city center on the peninsula should primarily be connected to the actual settlement focus on the opposite, eastern side of the Rhone. The first route, today's line A, was to follow the previous bus line 7 Perrache-Hôtel de Ville-Cusset, which had by far the highest number of passengers at the time and also opened up Villeurbanne, the second largest city in the Lyon area. This line was so significant that it was proposed as early as 1942. This section of the route initially had a length of 9.2 kilometers.

Apart from that, there were plans in the 1960s for the Part-Dieu -Quartier on a (former) barracks site on the east side of the Rhone. According to the will of the city administration, this should be redesigned into a second city center for Lyon - next to the peninsula - and therefore definitely included in the metro planning, specifically in the first construction phase. The Part-Dieu location was also important insofar as the future inner-city long-distance train station for the TGV was planned there.

Because Part-Dieu was about one kilometer south of the planned line A, the desired transport connection could not be achieved with this line. At the same time, the tight budget did not allow for too many additional kilometers. For this reason, a separate, approximately 1½-kilometer-long branch line was planned to connect Part-Dieu, which should branch off to the south between the Masséna and Charpennes stations and lead to the aforementioned area. This route corresponds to the northern section of today's line B.

The original intention of allowing the trains from Part-Dieu to join Line A with the help of a track triangle both in the direction of Perrache and in the direction of Cusset has been discarded again for technical reasons. Therefore, at Charpennes station, the situation now arises that the trains on line B end there a few meters in front of the tunnel of line A on a side platform and that this means that a change must be made between Part-Dieu and the peninsula within the metro network.

As a further addition, the connection of the Croix-Paquet rack railway to the Métronetz was planned. This approximately 600-meter-long railway line connected the peninsula with the Croix-Rousse high plateau to the north since 1890 and was originally designed as a funicular . The company had already been converted to rack and pinion drive by the TCL between 1972 and 1974 and equipped with modern vehicles. That line, henceforth referred to as line C, was to be extended by around 300 meters to the south in order to create a transfer option to line A at the Hôtel de Ville station. The first construction phase thus comprised around eleven kilometers of subway, which was spread over three lines.

Urban planning aspects

The Métro should not only solve the city's traffic problems, but also play a key role in the development of the city as a whole. Apart from Part-Dieu, the subway was also included in a number of other major urban development projects, such as the renovation of the Perrache train station and, in many cases, the renovation of the supply networks. In addition, a 1½ kilometer long pedestrian zone was built on the peninsula along the newly constructed Métrotunnel between the Perrache and Cordeliers stations by 1975 .

At the northern end of the peninsula, a block was demolished for the breakthrough of the Métro between the town hall and the banks of the Rhone and today's Place Louis Pradel was created. In order to cross the river, the adjacent Morand Bridge was also replaced by today's two-story new building. For the future, it was also planned to align the Métrolinien specifically to a number of large new building areas that were planned at the time on the outskirts of the city.

The role of central government in Paris

Those responsible on site knew from the start that the Métro would not be possible without financial participation from the central government. However, this type of financing was associated with various imponderables that had to be clarified. Apart from the fact that state aid was only to be expected to a limited extent, various aspects of metro construction were repeatedly called into question by the central government and thus became the subject of lengthy negotiations.

State grants of this kind were not granted in France at the time, i.e. before the country was decentralized in the 1980s, through generally available funds and could not be enforced on the basis of economic cost-benefit calculations. Instead, such funds had to be expressly included in the state economic plan, the design of which was the responsibility of the responsible ministries and was thus ultimately exposed to a certain arbitrariness on the part of the central government. The central government kept a metro in the province despite the meanwhile unambiguous results of the previous investigations for “ prestige attitude” and “waste” and also used various opportunities to present this publicly.

Even after the completion of all - at the time even centrally subsidized - planning for the first construction phase, the central government still questioned all previous specifications. In March 1971, a few months after the detailed planning was completed, it announced an ideas competition for the technical conception of the Métro, the specifications of which de facto ignored all previous planning steps and were intended to delay the construction of the Métro for another two years.

From the announcement to the opening

The calls for tenders for the ideas competition began in May 1971 and continued into 1972. Contrary to expectations by the central government, however, there were no changes to the previous concept, because the jury consisted of local managers who let the result of that call for tenders turn out just as they wanted.

A bidding consortium consisting of the Compagnie Générale d'Électricité (CGE) and Grands Travaux de Marseille (GTM) was ultimately awarded the contract . The pure construction costs were estimated at 596 million francs, of which 200 million francs were raised through state aid. Measured against the total costs of around 1.6 billion francs, the subsidy amount turned out to be quite small.

The official approval for the Métro was issued on October 23, 1972. After the supply networks had been relocated the following winter, construction work could begin on May 1, 1973. Almost five years later, on April 28, 1978, the three sections of the Métro were finally opened together.

The second construction phase

The planning for the second construction phase of the Métro began shortly after the construction work began. In addition to a few insignificant additions to the previous routes, the construction of two route sections was planned. On the one hand, line B from Part-Dieu was to be extended by 2.3 kilometers and three stations south to Place Jean Macé in order to better connect Part-Dieu and the TGV train station. On the other hand, the extension of line A to the east was planned in the area of Décines -Champ Blanc, where one of those new large housing estates had been planned for some time.

The latter building project increasingly contradicted the central state settlement planning, which provided for large new housing estates increasingly in rural regions and thus away from the big cities. As a result, the plans for the large Décines housing estate were abandoned and the second phase of construction was limited to the aforementioned 2.3 kilometers between Part-Dieu and Jean Macé. Construction work began in the winter of 1977/78, the opening took place on September 9, 1981, around two weeks before the first TGV reached Lyon.

The third construction phase after Cuire

When the metro was being built, there was a desire for an underground connection not only in Villeurbanne but also in other Lyon suburbs, including in the municipalities of Caluire-et-Cuire and Rillieux-la-Pape on the Croix-Rousse high plateau. The opportunity to do so was already available at the end of the 1970s, shortly after the Métro opened.

The traffic performance of the Croix-Paquet cogwheel railway, which had been connected to Line A at the Hôtel de Ville station since 1978, was no longer sufficient for the rush of passengers it caused. As a result, in the absence of suitable alternatives, the rolling stock and thus the workshop had to be replaced with more powerful units after just a few years. But because there was no space in the middle of the city for a new, correspondingly larger depot and there was no track connection to the rest of the metro network, the existing line had to be extended by about one kilometer to the north to a suitable piece of land for this purpose. In the course of this construction project, two more stations were built, Hénon and around one kilometer further north, today's Cuire terminus. The route opened on December 8, 1984.

The line D

Contrary to the previous course of the work, after the completion of the first construction phase, the greatest attention was originally not paid to lines B and C, but above all to line D today. In particular, the southeastern part of Lyon served by it had particularly poor transport connections at the time. In addition, a further Rhone crossing for the Métro should be built as soon as possible to better connect Part-Dieu to the peninsula.

However, due to its length and the technically complex crossing of the two rivers, the route was very expensive and, in contrast to the other two route sections, was difficult to finance. In addition, the connection of the Part-Dieu TGV station in the form of Line B received greater attention from the central government . In addition, the central government authorities apparently wanted to continue to deliberately delay the construction of the Métro, this time in favor of the financing of the Métro Marseille .

This attitude changed abruptly when the Mitterrand / Mauroy government took office in 1981. The cabinet, to which four ministers from the Communist Party (PCF) belonged, wanted to specifically promote local public transport and distributed the subsidies for metro construction much more generously than the previously incumbent center-right government. In this respect, the first phase of construction on Line D could not only be completed considerably faster than expected, but at the urging of the government it has now been extended considerably. Instead of the originally planned section Vieux Lyon – Parilly, the permit from Gorge de Loup to the Vénissieux train station was sufficient. This meant that the Métro should reach the urban area of a communist party stronghold on the southern edge of Greater Lyon. Construction began in 1984, and completion was originally scheduled for 1988.

The MAGGALY system

After a solution had been found for the Rhone crossing in the form of the bentonite shield drive, there was still a problem with the train protection. Originally, the same vehicles and the same systems for train protection and control were to be used on line D as on lines A and B. However, it was precisely at that time that it turned out that the system previously used for computer-aided operation was not as good desired worked. Therefore, in addition to the construction work and vehicles, the PA software and the PCC also had to be rewritten.

Against the background of the fully automatic and therefore driverless VAL-Métro in Lille, which had recently been successfully built by the French Matra Group , at the express request of SYTRAL, such a driverless subway was to be installed on Line D. Because a one-to-one copy of the VAL could not be realized in Lyon for structural reasons , a different one was created with the participation of other companies, namely Alcatel-Alsthom , Jeumont-Schneider and Compagnie de Signaux (CSEE) , and thus from scratch New solution to be developed called MAGGALY (Métro Automatique à Grand Gabarit de l'Agglomeration Lyonnaise). The responsibility for the implementation of the highly complex information technology systems was distributed in a rather clumsy way to the various companies and organizations, between which there were disagreements and persistent rivalries. In the end, the MAGGALY system was successfully implemented, but it was delayed by over three years and turned into a financial disaster with an increase in costs of several hundred million francs.

One of the reasons for these problematic decisions was the decentralization laws in France. With the creation of the regions and the associated reorganization of the municipal administration, the balance of power within SYTRAL and thus within the Métro project had shifted in favor of political officials and elected officials. In contrast to those responsible up to now, they were more concerned about their political reputation and made decisions more and more according to their political preferences and pushed aside many warnings from the technical experts.

The end of metro construction in the 1990s

The public was increasingly concerned about the cost and deadline overruns in the construction of Line D. Métro construction put a considerable strain on public finances and would also progress more slowly than previously planned for the foreseeable future. On the other hand, politicians in the greater Lyon area were forced to accelerate the expansion of their public transport networks due to the 1996 transport development plan (plan de déplacements urbains, PDU).

This was particularly true for the Lyon area, because after the opening of line D, the metro network still showed considerable deficits in terms of development. Neither the large university campus La Doua in the north-east of the city with its 35,000 students, nor the large sports facilities such as the Stade Gerland nor the airport in the east of the city had been connected by rapid transit systems. Likewise, the Métro had not yet reached a single one of the five large prefabricated building districts in the greater Lyon area.

It was therefore foreseeable that not all main traffic axes could be served by the subway, but that a cheaper alternative that could be implemented more quickly had to be found. In this respect, metro planning was reduced considerably with the introduction of the PDU for Greater Lyon in 1997. Instead, it was decided to build a tram network for the other main traffic axes, which has grown to five lines since it opened in 2000 (2013). This connects - together with the trolleybus network, which has been considerably expanded in the same period - the prefabricated building areas and the Doua site with the nearest metro stations. The airport is served by the Rhônexpress tram.

Only a few kilometers of new lines remained for the Métro. Line B was extended twice further south from Place Jean Macé, in 2000 to the Stade de Gerland and in 2013 further under the Rhone to Oullins. Line A was extended in 2007 by one station to the east in order to create a transfer option to the Rhônexpress at a newly built railway station. Since no further new lines are planned, the Métro Lyon is considered to be completed with the opening of the line to Oullins on December 11, 2013. However, two stations are planned along the existing line B, which will only be installed in a few years.

literature

- Stéphane Autran: Imaginer un métro pour Lyon: Des études préliminaires à l'inauguration de la première ligne 1960–1978 . (Études). Communauté urbaine de Lyon - Direction de la Prospective et du Dialogue Public, Lyon March 30, 2008 ( millenaire3.com [PDF; 2.4 MB ; accessed on December 11, 2013]).

- Christoph Groneck: New trams in France. The return of an urban means of transport . EK-Verlag, Freiburg 2003, ISBN 3-88255-844-X , p. 120 ff .

- Christoph Groneck: Metros in France: Paris, Marseille, Lyon, Lille, Toulouse, Rennes, Rouen & Laon . Schwandl, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-936573-13-1 , p. 92 ff .

- Guy et Marjorie Borge, René Clavaud: Les transports à Lyon. You tram au metro . Ed .: Jean Honoré. J. Honoré, Lyon 1984, ISBN 2-903460-08-6 .

- René Waldmann: La grande Traboule . Ed. Lyonnaises d'Art et d'Histoire, Lyon 1991, ISBN 2-905230-49-5 .

- René Waldmann: Les Charmes de Maggaly . Ed. Lyonnaises d'Art et d'Historie, Lyon 1993, ISBN 2-905230-95-9 .

Web links

- TCL, Transports en Commun de l'agglomération de Lyon: Metro, tram, bus. Keolis Lyon, accessed on October 30, 2013 (website of the executing company Keolis Lyon).

- Accueil. Syndicat Mixte des Transports pour le Rhône et l'agglomération lyonnaise, accessed on October 30, 2013 (website of the SYTRAL transport association).

- Metro Lyon (sic!) - Line D (1990). Hochtief, 1990, accessed on November 2, 2013 (film about the construction of Line D of Métro Lyon).

- Ferro-Lyon. Retrieved March 3, 2010 (comprehensive, private page on local transport in the Lyon region).

Individual evidence

- ^ Nouvel Aménagement des rames de Métro: Les rames de métro font peau neuve. SYTRAL - Syndicat mixte des Transports pour le Rhône et l'Agglomération Lyonnaise, 2013, archived from the original on November 2, 2011 ; Retrieved November 20, 2014 .

- ^ Nouvel Aménagement des rames de Métro: Les rames de métro font peau neuve. SYTRAL - Syndicat mixte des Transports pour le Rhône et l'Agglomération Lyonnaise, 2013, archived from the original on November 2, 2011 ; Retrieved October 30, 2013 . and Le Métro sur le réseau TCL. SYTRAL - Syndicat mixte des Transports pour le Rhône et l'Agglomération Lyonnaise, 2013, archived from the original on October 8, 2014 ; Retrieved October 30, 2013 .

- ↑ a b c d Nouvel Aménagement des rames de Métro: Les rames de métro font peau neuve. SYTRAL - Syndicat mixte des Transports pour le Rhône et l'Agglomération Lyonnaise, 2013, archived from the original on November 2, 2011 ; Retrieved October 30, 2013 .

- ↑ Waldmann: La Grande Traboule. 1991, p. 161 (quoted from: Le Figaro, February 17, 1973).

- ↑ Autran: Imaginer un métro pour Lyon. 2008, p. 37 and Waldmann: Les Charmes de Maggaly. 1993, p. 56.

- ↑ La délégation de service public. SYTRAL - Syndicat mixte des Transports pour le Rhône et l'Agglomération Lyonnaise, 2011, accessed on October 30, 2013 .

- ↑ SYTRAL: RAPPORT FINANCIER ANNUEL 2012. (PDF) SYTRAL - Syndicat mixte des Transports pour le Rhône et l'Agglomération Lyonnaise, June 12, 2013, accessed on October 30, 2013 .

- ↑ In any case, corresponding considerations led to the automation of line D, see Waldmann: Les Charmes de Maggaly. 1993, p. 214ff.

- ↑ Le pilotage automatique intégral. SYTRAL - Syndicat mixte des Transports pour le Rhône et l'Agglomération Lyonnaise, 2011, archived from the original on November 29, 2014 ; Retrieved November 2, 2013 .

- ↑ http://www.sytral.fr/525-pilotage-automatique.htm

- ^ A b Christoph Groneck: Metros in France . 1st edition. Robert Schwandl, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-936573-13-1 , p. 100 f .

- ↑ L'infrastructure. ferro-lyon.net, April 25, 2012, accessed November 2, 2013 .

- ↑ Stadtverkehr 11–12 / 1981, p. 470.

- ↑ Le Métro sur le réseau TCL. SYTRAL - Syndicat mixte des Transports pour le Rhône et l'Agglomération Lyonnaise, 2013, archived from the original on October 8, 2014 ; Retrieved October 30, 2013 .

- ↑ Waldmann: Les Charmes de Maggaly. 1993, p. 56.

- ↑ L'unité de transport métro D. ferro-lyon.net, May 2, 2013, accessed on November 2, 2013 .

- ↑ Waldmann: La grande Traboule. 1991, p. 171ff. and Autran: Imaginer un métro pour Lyon. 2008, p. 18ff.

- ↑ Waldmann: La grande Traboule. 1991, p. 171ff.

- ↑ Waldmann: La grande Traboule. 1991, p. 180ff.

- ↑ a b Waldmann: Les Charmes de Maggaly. 1993, p. 84ff.

- ↑ Waldmann: Les Charmes de Maggaly. 1993, p. 84ff. as well as Metro Lyon (sic!) - Line D (1990). Hochtief, 1990, accessed on November 2, 2013 (documentary about the construction of Line D).

- ^ Syndicat Mixte des Transports pour le Rhône et l'agglomération lyonnaise (ed.): Chroniques du Métro B: Le Creusement du Tunnel: Prolongement Lyon-Gerland> Oullins . April 2012.

- ↑ a b c Waldmann: La grande Traboule. 1991, pp. 201ff.

- ↑ Autran: Imaginer un métro pour Lyon. 2008, p. 21f.

- ↑ a b Waldmann: La grande Traboule. 1991, p. 201.

- ↑ TCL - Info trafic. KEOLIS LYON. Retrieved November 3, 2013 . and TCL - Alerte accessibilité. KEOLIS LYON. Retrieved November 3, 2013 .

- ↑ TCL -Toutes les lignes. KEOLIS LYON. Retrieved November 3, 2013 . and TCL - Itinéraires. KEOLIS LYON. Retrieved November 3, 2013 .

- ↑ Realizations of VINCI Energies in the domaine des transports en commun. 2013, archived from the original on November 4, 2011 ; Retrieved October 25, 2013 .

- ↑ Waldmann: La grande Traboule. 1991, p. 201. and Ferro-Lyon - Les lignes A & B - Signalisation et équipements de sécurité. ferro-lyon.net, May 4, 2013, accessed November 26, 2013 .

- ↑ Waldmann: Les Charmes de Maggaly. 1993, p. 225.

- ↑ a b c d Ferro-Lyon - Les lignes A & B - Signalisation et équipements de sécurité. ferro-lyon.net, May 4, 2013, accessed November 26, 2013 .

- ↑ In fact, in the first few years there were very frequent breakdowns of the route computer , so that these signals had to be used regularly, see Waldmann: Les Charmes de Maggaly. 1993, p. 206.

- ↑ Ferro-Lyon - Métro C - La signalisation et les équipements de sécurité. ferro-lyon.net, November 15, 2008, accessed November 3, 2013 .

- ^ A b Les Divisions Rail Systems et Mobility and Logistics de Siemens France. (PDF) Siemens SAS: Secteur Infrastructure & Cities: Division Rail Systems: Division Mobility and Logistics, November 2011, p. 2 , accessed on November 26, 2013 .

- ↑ Waldmann: Les Charmes de Maggaly. 1993, pp. 205ff.

- ↑ Ferro-Lyon - La ligne D - Signalisation et équipements. ferro-lyon.net, May 2, 2013, p. 1 , accessed December 6, 2013 .

- ↑ Ferro-Lyon - La ligne D - Signalisation et équipements. ferro-lyon.net, May 2, 2013, p. 2 , accessed December 6, 2013 .

- ↑ JM Erbina, C. Soulas: Twenty Years of Experiences with DRIVERLESS METROS in France . 19th Transport Science Days, [22. and September 23, 2003 in Dresden]. In: Mobility and Traffic Management in a Networked World . Techn. Univ., Fac. Traffic Science. Friedrich List, Dresden 2003 ( 19th Transport Science Days: Mobility and Traffic Management in a Networked World ).

- ↑ a b c d e f Ferro-Lyon - Le MPL75 (sic!). ferro-lyon.net, October 27, 2013, accessed December 7, 2013 .

- ↑ Waldmann: La grande Traboule. 1991, p. 197.

- ↑ a b c d Ferro-Lyon - Le MCL80 (sic!). ferro-lyon.net, January 7, 2012, accessed December 7, 2013 .

- ↑ For further comparison: A subway train of the type C2 of the Munich subway with six cars cost around 8.8 million euros (2014), see The new subway for Munich: Even more space, comfort and safety . (PDF) Stadtwerke München GmbH, press office, February 21, 2014, archived from the original on July 9, 2014 ; Retrieved on November 20, 2014 (press release from Stadtwerke München).

- ↑ a b Ferro-Lyon - Le MPL85 (sic!). ferro-lyon.net, May 2, 2013, accessed December 7, 2013 .

- ↑ mobilicites.com of October 26, 2016: Alstom remporte un contrat de 140 millions d'euros pour le métro de Lyon ; Retrieved on November 3, 2016 (French) ( Memento from November 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Waldmann: La grande Traboule. 1991, p. 11ff.

- ↑ Waldmann: La grande Traboule. 1991, p. 43f and p. 56f. - For the French economic model in general, see also The French economic model: market economy with a strong state. Federal Agency for Civic Education (bpb), January 21, 2013, accessed on November 11, 2013 .

- ↑ Waldmann: La grande Traboule. 1991, p. 51ff.

- ↑ Waldmann: La grande Traboule. 1991, pp. 55f.

- ↑ Waldmann: La grande Traboule. 1991, p. 44ff.

- ↑ Waldmann: La grande Traboule. 1991, p. 70ff. and Autran: Imaginer un métro pour Lyon. 2008, p. 3ff.

- ↑ Waldmann: La grande Traboule. 1991, p. 100.

- ↑ Autran: Imaginer un métro pour Lyon. 2008, p. 6f.

- ↑ Autran: Imaginer un métro pour Lyon. 2008, p. 6f and p. 23f.

- ↑ Waldmann: La grande Traboule. 1991, pp. 145f. and Autran: Imaginer un métro pour Lyon. 2008, p. 6f.

- ^ "La [...] RATP [...] se répand non seulement sur toute la France mais sur toute la planète comme" le "boureau national d'ingénierie dans le domaine des métros" Waldmann: Les Charmes de Maggaly. 1993, pp. 207f.

- ↑ Waldmann: La grande Traboule. 1991, p. 105ff.

- ↑ Waldmann: La grande Traboule. 1991, p. 74.

- ↑ Waldmann: La grande Traboule. 1991, p. 27ff.

- ↑ Waldmann: La grande Traboule. 1991, p. 86, Waldmann: La grande Traboule. 1991, p. 97. and Autran: Imaginer un métro pour Lyon. 2008, p. 9f.

- ↑ Autran: Imaginer un métro pour Lyon. 2008, p. 9f.

- ↑ Waldmann: La grande Traboule. 1991, p. 119 and Waldmann: Les Charmes de Maggaly. 1993, p. 18.

- ↑ Waldmann: La grande Traboule. 1991, p. 97, Waldmann: La grande Traboule. 1991, p. 133ff. and Waldmann: Les Charmes de Maggaly. 1993, p. 37ff.

- ↑ Waldmann: La grande Traboule. 1991, pp. 201ff. and Waldmann: Les Charmes de Maggaly. 1993, p. 9ff.

- ↑ Waldmann: La grande Traboule. 1991, p. 56.

- ↑ a b Autran: Imaginer un métro pour Lyon. 2008, p. 7f.

- ↑ Waldmann: Les Charmes de Maggaly. 1993, pp. 55f.

- ↑ Autran: Imaginer un métro pour Lyon. 2008, p. 17 and Waldmann: La grande Traboule. 1991, p. 147ff. - In this context, Figaro commented on the history of Métro Lyon as "above all that of a misunderstanding [...] between an omnipotent central state" and the province, which " demands emancipation " from it. In view of the metro project in Lyon, Paris think “of this fable of the frog who wanted to be as big as an ox”. Waldmann: La grande traboule. 1991, p. 161 (quoted from: Le Figaro, February 17, 1973).

- ↑ a b Waldmann: La grande Traboule. 1991, p. 147ff.

- ↑ Waldmann: Les Charmes de Maggaly. 1993, p. 289.

- ↑ Waldmann: La grande Traboule. 1991, p. 165.

- ↑ Autran: Imaginer un métro pour Lyon. 2008, p. 18.

- ↑ Autran: Imaginer un métro pour Lyon. 2008, p. 26.

- ↑ a b Waldmann: Les Charmes de Maggaly. 1993, p. 7ff.

- ↑ a b Waldmann: Les Charmes de Maggaly. 1993, p. 37ff.

- ↑ a b c d Waldmann: Les Charmes de Maggaly. 1993, p. 57ff.

- ↑ Waldmann: Les Charmes de Maggaly. 1993, pp. 21f.

- ↑ a b Waldmann: Les Charmes de Maggaly. 1993, p. 210ff.

- ^ Jörg Schütte: The automation system of the Météor line in Paris . In: Eisenbahn-Revue International . November 1997, p. 542-547 .

- ^ "La conséquence d'une mauvaise organization, de chaque côté de la barrière", Waldmann: Les Charmes de Maggaly. 1993, p. 285.

- ↑ Waldmann: Les Charmes de Maggaly. 1993, p. 129ff. and p. 210ff.

- ^ A b Groneck: New trams in France. The return of an urban means of transport , 2003, p. 120ff.