Menslager reading society

The Menslager Reading Society , founded in 1796, was a reading society in the Artländer parish of Menslage . It was one of the rare reading societies that was open to all classes, all professions and both sexes across all classes. The Menslager Lesegesellschaft refutes the notion that the educational gap only slowly dwindled in the late 19th century and the often gloomy picture of educational conditions in rural areas where sufficient education, contact with writing and thus the development of a writing and reading culture are not possible should have been.

The Menslager Reading Society, which has been handed down with a comparatively rich amount of material, was neither a pedagogically motivated event in the Age of Enlightenment by dignitaries from rural areas to educate the rural folk who had stayed behind, nor was it an institution for local bourgeois elites. Nor was it a means of learning or spreading reading, but rather the targeted response to already existing, differentiated reading needs and thus an institution of organized reading that grew out of the desire of the population of the Artländer parish, whose village classes were almost completely literate around 1800 . Rather, it can be classified according to the term introduced by Georg Jäger , Alberto Martino and Reinhard Wittmann as an "encyclopedic reading society" which "primarily provided non-fiction literature for an enlightened audience."

Another peculiarity was the extensive lack of magazines in the holdings of the Menslager Reading Society, since otherwise periodicals are considered to be the most important foundation stock or even cause of a foundation.

After all, what is unusual about the reading society is its comparatively long existence of around 100 years.

background

Reading and book production in the 17th and 18th centuries

In the 17th and early 18th centuries, books in Western Europe were mainly written by scholars for scholars in the form of scientific works, mainly on theology and in Latin . A literary reading public in the modern sense did not exist; The offer for laypeople was limited to revision reading, such as religious devotional literature , which spread noticeably around 1700, as well as practical literature such as medical or legal books and general reference works . German-language fiction was hardly published.

The remained book production initially far behind distribution and conditions of the early 17th century rise of newspapers and magazines back, the first mass media , the media landscape of the early modern period fundamentally changed and introduced a new form of reading. Newspaper reading quickly penetrated the broader classes, as not only scientific journals, but also popular magazines were offered.

The offer of more books in German, a shift in content from religious to fiction literature and a change in book formats ( smaller, more manageable book formats instead of tome or quart ) caused a change in reading behavior from the late 17th century. In general, there was a transition from intensive and repetitive reading, such as edification literature , to extensive, entertaining or informative reading. Initially, in addition to small forms such as essays or tracts , instructive and informative literature as well as lexicons , anthologies , and compendia played a dominant role until more and more aesthetic and entertaining literature was offered.

Supported by the instrument of the reading society, a middle-class reading culture developed. The emergence of reading societies was not only due to the political and social developments in the Age of Enlightenment or the influences of Vormärz and Biedermeier , but were also facilitated by this simultaneous revolution in the book market , which rose sharply after the stagnation of book printing in the 17th century of book production.

Literacy, reading behavior, writing and reading culture

A broad-based historical literacy research, as it has long been carried out in other countries, is still pending for the German-speaking area. In German-language research, literacy is usually conceptually narrowly defined and related to the elementary access to the respective script and the use of the characters . Accordingly, when researching the level of literacy, mainly serially available sources, such as signatures in marriage registers , are evaluated, which have been available for around 200 years, namely since the introduction of the civil status registers and the registry offices .

Reading (and understanding) literature, i.e. the development of a reading culture, presupposes a clearly advanced level of literacy and a certain amount of general knowledge and education . For this reason, too, an effort arose from the early 18th century to significantly improve the elementary school system , albeit limited to certain regions. Among other things, a certain level of prosperity in the region was required, which enabled schools to be maintained and teachers to be employed financially, and which allowed the population not to see their children primarily as an indispensable workforce; on the other hand, Protestantism promoted literacy and reading culture - prerequisites which the Protestant Artland met with its prosperous rural culture.

In research, there has long been a close connection between the level of literacy and socio-economic progress, with a contrast between a city that promotes education and a country that is less educated. Recent research has increasingly challenged this model. But Reinhard Wittmann, too, in his history of the German book trade continues from the figures of Engelsing and R. Schenda, according to which “by 1770 ... the number of literate readers rose to 15 percent, by 1800 to 25 percent, in 1840 40 percent and 1870 75 percent had already been achieved ” , but also admits that these figures are hardly based on empirical data. Nonetheless, he quotes a “Swabian Enlightenment Pastor” who is said to have summed up in 1793: “The child hardly learns to spell, never read anything with understanding, hardly write his name, never put anything out of his head on paper, his catechism stammered without anything from Knowing the content ... it stays in his life. "

In his New German History, the historian Peter Moraw assumes that the numbers are not dissimilar, but also states: “If you look at individual localities, you come to astonishing observations. In the Osnabrück parish of Menslage, almost all rural residents could read around 1800. In pietistic embossed Laichingen on the Swabian Alb had late 18th century, 94.5 percent of all families by Weber poorest to the richest farmers more than two books. "

According to Anne Conrad, the few regional studies on literacy available to date suggest that reading skills were more widespread than previously assumed. The view has also increasingly gained acceptance that the motivation to read is the most important factor in the reception of writings.

Karl-Heinz Ziessow comes to the same results, who in his study of the Artländer parish of Menslage evaluated, among other things, the civil status registers from the French period, which are available for the period from 1808 to autumn 1813. According to this, Menslage offers the appearance of a parish equipped with a very high degree of signability in 1810: 84.35 percent of the approximately 2,870 inhabitants around 1810 certified the act of marriage with their own signature. The gender gap in Menslage, with a good 81 percent of women who were able to sign, was at an untypically narrow gap for other areas in Central Europe.

Reading Society Research

Due to the source situation, reading society research concentrates on the analysis of urban reading societies and especially on the class of the upper urban bourgeoisie. Rural reading societies have been examined much less often and the academic position often follows Irene Jentsch, who in her dissertation from the 1930s takes the view that rural reading societies are hierarchically structured events of local dignitaries for the limited education of the uneducated village population and more "reading" because reading societies have been. A typical formulation of this position comes from Felicitas Marwinksi, who wrote in 1981:

- The rural LGGs were mostly short-lived at the end of the 18th century. The reasons can be seen in the fact that there were only a few writings that were especially suitable for the educational level of the rural population (such as Rudolph Zacharias Becker's 'Not- und Helfsbüchlein'), that the rural school system was still too underdeveloped and that there was great interest among the farmers Was subject to fluctuations. In addition, the Enlightenment movement at this time was more oriented towards urban intelligence.

The Frankenhausen reading society examined by Marvinski actually existed for only nine years (1795–1804), the Gernsbach reading society just two and the German reading society (1814-1819) five years. However, the Elberfeld Reading Society, founded in 1775, was one of the first educational societies in the Rhineland and was only dissolved in 1818. The two reading societies Henriette von Pogwischs (1776-1851) each existed for more than 20 years, and there were reading societies that existed for as long as or longer than the Menslager reading society, such as the Eppingen reading society or the Rüti Swiss reading society , which were even 141 years old duration. The Bülach Reading Society, founded in 1818, still exists today. These examples show that the state of research on rural reading societies in Switzerland is significantly better than in Germany, where it was found that some rural reading societies were highly respected intellectual discussion groups.

Hilmar Tilgner wrote in his dissertation from 2001: In them [the reading societies] the aristocratic-bourgeois intelligentsia came together ...

The analysis of the school and educational history of the Osnabrück region , which the historian Karl-Heinz Ziessow , custodian of the Lower Saxony Open Air Museum Cloppenburg , began in the 1980s and which also included the Menslager Reading Society, paints a completely different picture. Among other things, Ziessow was able to draw on more than 200 historical court and craft archives and the extensive archive materials of the museum village, which concern the relocated schoolhouse of the Renslager secondary school. These extensive files are particularly interesting because the founder of the Menslager Reading Society, Berend Foeth, taught at the Renslager secondary school at the end of the 18th century and the later head of the reading society, Pastor Bernhard Möllmann, was responsible for overseeing the schools in the parish. On the basis of these documents, Ziessow established that the lack of educational conditions allegedly prevalent in rural regions at the end of the 18th century did not apply, at least in Artland.

Another study, a master's thesis by Ortrud Deister from the University of Mainz from 1996 on the subject of rural reading culture in the late Empire 1900–1915, presented at Gau-Algesheim, Rheinhessen, provides similar results and shows that general statements about rural intellectual backwardness and one are only starting the dwindling educational gap in the late 19th century cannot be made.

There were, of course, examples that support these prejudices: For example, the reading society Gernsbach, which was founded late in 1847 and mentioned above, offered mainly entertainment literature in the short time of its existence, organized pure entertainment meetings, such as singing games, and failed its female members, although even three Women were among the founding members, the right to vote.

Regional background

In his work from 1801 On a critical pilgrimage between the Rhine and Weser , Justus von Gruner also discusses the Artland, which he distinguishes from other parts of the bishopric: “... in the so-called Artlande ... (part of the Fürstenau office) ... where the best are Aekker and meadows, and there are extremely wealthy peasants. "

Gruner is particularly impressed by the level of education: “In general, however, this (note: education) is much more advanced here, and the people are far more cultured than in Münster and the other Westphalian donors. The cause of this may mostly lie in the mixing of the religious parties, since about one half of the parishes is Catholic and the other is Lutheran, and several places have residents of both parts, between whom there is now on average a lot of tolerance and peacefulness. "

With regard to the Enlightenment , Gruner goes once again specifically to the Artland: "Nevertheless, the honest inhabitants are noticeably advancing in the Enlightenment, for which the enlightened teaching style of the preachers, their frequent trips to the cities ... and the general spirit of the time, may contribute most, because he is very enlightened (especially in Artlande) and sometimes quite free ... there is a lot of reading in the flat country too. "

The image sources from this period are a series of paper cuttings made by the Bonn painter and silhouette artist Johann Caspar Dilly (1767–1841) when he came to Artland as a traveling artist at the beginning of the 19th century and spent a long time in nearby Essen / Oldenburg settled. Strikingly often he shows people reading or speaking, like here the children of a canteen forest ranger family or a reading farmer's wife. From the “detailed and sharply defined” portraits, which were discovered by folklore research around 1980 as source material for the Biedermeier era, it is also clear that the population dressed in modern clothes and not in rural costume.

These contemporary representations confirm Ziessow's statements about the level of education in Artland. In his dissertation on reading societies, he demonstrates that education was of great importance across all classes in the early 19th century. After evaluating the civil status registers, he found: “... that the intensive school provision in the parish of Menslage had been crowned with extraordinary success and had already established a literacy level at the beginning of the 19th century that needed no comparison in Europe . Menslage as part of the 'Protestant cultural island' could be regarded as fully literate around 1810 and had reached an 'urban level' in the acquisition of cultural techniques. "

It is unknown whether Gruner and Dilly were aware of the Menslager Reading Society, and it remains unclear whether Gruner acquired his knowledge of the Artländer himself or was perhaps only informed by local pastors. However, it seems that the rural population in Artland had a special position in the Osnabrück Monastery in terms of prosperity, education and the level of education.

The population of the parish also maintained an unusually lively correspondence with one another; Möllmann even asked for the delivery of pastors' sheaves from the farmers in writing. In the more than Artländer court archives in the possession of the Cloppenburg Museumsdorf, most of which have not yet been evaluated, there are a number of fluent but carefully worded letters that the residents exchanged with one another. Three letters from Heinrich Schwietert to Bernhard Scherhage from 1824 to 1826 in which agricultural issues are discussed have been preserved in the Oing-Ellerlage court archive .

The farmer Bernhard Scherhage, a member of the Menslager Reading Society (see also below), is regarded in folklore research as another “example of literate peasant self-enlightenment” of the late 18th century: “... he excerpted everything worth knowing from the circulating newspapers and Books. About 600 sheets of his records have been preserved in a court archive ... even on Kant's 'Critique of Pure Reason'. His mastery of self-directed writing down of what he has read goes back to the good writing lessons in secondary schools, which large and medium-sized farmers were able to control through the choice of teachers. An exercise book has been preserved containing entries by Bernhard Scherhage and his father and other relatives over two generations from 1767 to 1817. They contain mostly clean, almost error-free spelling, in several fonts, e.g. Sometimes decorated with calligraphy, religious texts and rules about writing technique and orthography ... "

A letter sent to Scherhage by Georg Hermann Friedrich Lehner's teacher son Georg Hermann Friedrich Lehner in 1829 shows the interest in the history and contemporary events of this young, obviously well-educated Artlander generation: “On Sunday evening I went to the [note: Osnabrück] town hall, where there was a large collection Wax figures could be seen, life-size ... you can find a Wieland and Kant ..., a Voltaire and Franklin as well as a Frederick the Great, Joseph II, Catharina II of Russia, in their usual positions and costumes ... a Johann von Leyden how he judges his wife, Maria Stuart, Napoleon ... the bookseller Palm, the Admiral de Ruyter ... If you weren't that far from here, I would ask you to come and see this. "

Another collectively written exercise book from the parish of Menslage "proves a post-elementary education by private teachers or Latin school" . The entries of a 17-year-old Susanna Katharina Dürfeld and her relatives from 1793 "testify to well-developed writing and calligraphic skills, which were important as a social educational symbol in the country even for infrequent writers until the 20th century."

population

Menslage, consisting of the village of Menslage, the farmers Andorf, Borg, Bottorf, Hahlen, Herbergen, Klein Mimmelage, Renslage, Schandorf, Wasserhausen and Wierup as well as the Mundelnburg estate had around 2700 inhabitants in the beginning of the 18th century, with the village itself less than 100 inhabitants and the Hahlen farming community was the largest with more than 500 inhabitants.

The parish of Menslage was first mentioned in 1187, the Protestant St. Mary's Church dates from 1244. In the last days of the Second World War , the church and the historic church corner (a half-timbered bar that formed the outer end of the fortified church) fell victim to a bomb attack and was largely destroyed. The faithful reconstruction of the entire ensemble, recorded immediately after the end of the war, was largely completed in 1954. The half-timbered houses of the Kirchwinkel are reminiscent of the early settlement of shopkeepers and craftsmen, who laid the foundation for a demographic and functional specialization of the church village as a service center as early as the 12th and 13th centuries.

The main occupation of the residents has always been agriculture. Oats , rye , barley and the more demanding wheat could be grown on the fertile arable land . After grain surpluses were often recorded, the Artland was referred to as the granary of the bishopric of Osnabrück . Over the centuries, this led to the emergence of a wealthy rural upper class. This prosperity is still visible today in the large number of magnificent old farms that are combined to form the Artland cultural treasure . In 1830 the peasants were liberated ; At that time there were still 134 serf farms in the parish, despite all the prosperity , which were ransomed by 1850. This is all the more astonishing since the currents of the Enlightenment in the community were introduced practically a generation before the peasant liberation and achieved great success.

The distribution of real estate in the north of Osnabrück was largely completed with the restrictive land allocation in the 16th century. There were no serious changes in the following centuries, either in number or in their composition. The four so-called heritage classes the sole heirs , Halberben , Erbkotten and Mark cottas were politically and fiscally the peasantry. Other groups of rural settlers were the Brinksitzer , Wördener and Kirchhöfer .

What was remarkable in this northern part of the Principality of Osnabrück was the extensive lack of rural workers , which is mainly attributed to the scattered location of the Artländer farms, which made settlement difficult, as farm workers were forced to help on several farms and depending on the workload. On the other hand, the trainee system , which began in the 16th century with the leasing of body breeds , played an even greater role .

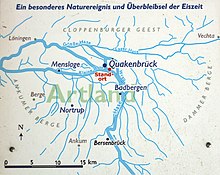

Geographical influences

Menslage and its neighboring churches are located in Artlandes , the name of which has been used for this area since 1309 and which - if the area is viewed as a landscape structure - extends within the glacial terminal moraine arc of the Dammer and Bippen mountains . After the end of the Ice Age, the area was a large meltwater basin that was filled with alluvial sand by Hase and Wrau . The areas created in this way enabled productive agriculture, which over centuries shaped the rural landscape that is still today.

Artland was never a political unit. There have never been clear, permanent territorial boundaries, and the term Artland has been used to varying degrees over the centuries. His parishes did not even belong to the same offices of the bishopric of Osnabrück . Rather, economic, cultural and family ties made the Artland a closed unit.

The prerequisites for the economic independence of the Artland were the good natural conditions and the very productive soils in the "Quakenbrücker Basin". Due to its low incline in the plains below Bersenbrück, the hare was responsible for the deposition of fertile alluvial sands (alluvial sand) from the Osnabrück mountainous region, from which very fertile arable land could develop. The higher ash soils were upgraded by means of pest management , which was taken from the rich meadows. In addition to the cattle breeding that prevailed in the entire Osnabrück region up to the Thirty Years' War , arable farming has always been practiced in Artland , whereby in addition to oats and rye , the more demanding and coveted barley could be grown. This productive arable land, which in contrast to the rest of the Osnabrück region, which often suffered from a lack of grain, led to the development of a wealthy rural upper class with numerous individual courtyards in the "granary of the Osnabrück Monastery", which together with hedges, forests and oak ridges created a park-like landscape.

Educational and school history

As a purely Protestant parish, Menslage was surrounded by all variants of parish constitutions that were possible in the confessionally mixed territory of Osnabrück after the compromise on power politics enshrined in the Peace of Westphalia and in the Capitulatio perpetua . At that time, in accordance with the church regulations laid down for the Osnabrück Monastery , each parish only had schools of the particular denomination. In the purely Catholic parishes (such as Ankum ) there were Catholic schools and in the Protestant parishes (such as Bippen , Börstel , Menslage ) Protestant schools, whose teachers mostly also held the office of sexton or organist . In the places where both denominations had asserted their place (e.g. in Quakenbrück , Badbergen , Vörden ), there were Catholic and Protestant schools.

The need for schools for the children of the Protestant peasantry in the one-parish Catholic parishes of Ankum and Berge , who could not be looked after under the real parish compulsion that existed until 1786, prompted the establishment of a secondary school in the Menslager area from the middle of the 18th century .

The Renslager School was operated from 1751 to 1891; The schoolhouse in the Cloppenburg museum village, faithfully rebuilt, consisted of a single room measuring 5.80 by 4.20 meters, i.e. not even 25 square meters, in which 50 to 60 children from the Renslage and Dalvers (Altkreis Bersenbrück ) farmers were taught. This development continued into the 19th century with the establishment of further schools and created an increasingly extensive network of school facilities on the territory of the parish, so that by 1800 all the village classes were almost completely literate.

Since the secondary schools, unlike the Winkelschulen, had their own school buildings and, due to the denominational relationships in Artland, had a particularly secure position, the hired workers , farmers or craftsmen who worked at them as teaching staff could make lessons their main source of income. The social position of these teachers thus experienced an appreciation and the already comparatively strong position of the farmers in the parish was further strengthened by the establishment of their own schools.

The fact that the only secondary school in the Osnabrück region for centuries, the Quakenbrück Latin School (today's Artland Gymnasium ), is not far from Menslage and was accessible to the students there, also had a positive effect on the education and upbringing of the children of the parish .

Literature offer

Another condition for an increasing use of written media was the expansion of a comparatively modest, but constantly active book trade and bookbinding trade into the parishes of the rural area. Menslage also benefited from its proximity to the town of Quakenbrück, where regular book fairs took place, because in the 18th century book exchange was still the most common form of transport alongside travel and mail order. Publishing and the book trade were still disorganized, and the bookselling profession did not emerge until the 19th century.

Therefore, whoever felt called to deal with books and other printed works; guild membership was not required. In addition to shopkeepers, retailers and peddlers, it was mainly the bookbinders who took care of the book trade. In a report from 1811 to the sub-prefect of the Oberemsdepartment , four people from the region were listed who traded livres de prière et d'instruction , devotional and school books: Karl Backhäuser for 20 years, the widow Backhäuser for 20 years, August Wilhelm Linnemann for a year, each from Quakenbrück and Friedrich Meyer from Badbergen for 11 years. Customers who were looking for a larger selection of books used various bookseller catalogs to order by post or drove to Osnabrück or Oldenburg .

While the first Oldenburg book printing company was established in 1599, Osnabrück followed relatively late, but was at least represented in the printing industry from 1617, first with the printing company Martin Mann and from 1707 with Gottfried Kißling from Eulenburg (Saxony). Even if the book trade was already well developed at that time to supply even remote regions with literature, regional print shops opened up additional possibilities in the area of short-lived written material or regional topics. For example, Kißling printed the laws and ordinances, hymn books, catechisms, school books and primers and, from 1766, the weekly Osnabrück Advertisements , a "Advertisement and Intelligence Gazette ". The first Osnabrück newspaper is documented as early as 1676.

In Menslage there were on the road connecting to Quakenbrück a post and way station with colonial warehouses and public Viehwaage. Since the post offices were responsible for the distribution of newspapers and magazines to the subscribers, the residents of the Menslager were likely to have been given preference over the neighboring parishes, at least in terms of reception of these media.

The Menslager Reading Society

The first trace of a reading association in the parish of Menslage not far from the town of Quakenbrück is a list of seven names from 1796, which can be found on the flyleaf of the second edition of the book About Revolutions, their sources and the means against it by Johann Ludwig Ewald , published in 1793 . The canteen pastor Möllmann and his colleague Varenhorst from Bippen, the teacher Berend Foeth, as well as court and personal names are listed. It is unclear whether this is just a joint purchase of books in the sense of a reading circle or whether the reading society was just beginning.

The turn of the century from the 18th to the 19th century was a restless and politically changeable time even for the Osnabrück region. The Principality of Osnabrück, which emerged from the bishopric of Osnabrück in 1802, was added to Hanover in 1803 by the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss , in 1806 briefly belonged to Prussia and from 1807 to the Kingdom of Westphalia . In 1810 it fell to France; Until the fall of Napoléon, the Osnabrück region belonged to the French Département de l'Ems-Supérieur (department of the Upper Ems) with the capital Osnabrück, and Menslage was one of 56 mayorries ( Mairie ) in the Arrondissement Quakenbrück. In 1815 the Osnabrück region fell back to Hanover, where it remained until 1866. In that year, Prussia annexed the Kingdom of Hanover as a result of the German War , so that the former Prince Diocese of Osnabrück also came to Prussia.

The founding of the reading society falls not only in this politically uneasy time, but also in the Age of Enlightenment, in which literature was of enormous importance in order to disseminate new ideas and food for thought and to teach what was in some cases almost epidemic general reading culture and the founding of an enormous number of reading societies. On the basis of his research, Ziessow summed up that “the Menslager Reading Society of 1811 is an association with a fixed membership fee, free choice of books and ongoing book exchange, but without regular meetings” . The conditions under the direction of Berend Foeth are also to be classified here, "since the continuous entries on the inside of the book cover from that time testify to a book circulation similar to that in Möllmann's time" .

founding

Neither organized meetings for the purpose of discussion or evaluation of the reading material nor organized readings have been handed down for the Menslager Reading Society. Although at least informal meetings must have taken place, as can be seen indirectly from the records, the correspondence between one another was important and crucial for the good functioning of the reading community. The information situation is correspondingly good. Complete lists of members can be found on the inside of the book cover, on interleaves, appendices and on the accounts of purchased books, the first of which dates back to 1802 and the last of which dates from 1839. In addition, Möllmann, the second director, has created a large number of circulars , most of which are preserved in his estate, which is now in the archive of the museum village of Cloppenburg.

No direct documents have been preserved about the founding of 1796. Foeth left far fewer records than Möllmann. Also whether and how long the reading society continued to exist after the death of its founder in 1801 cannot be said. It can be assumed, however, that until the revival in 1811 no new acquisitions were made, the writings in circulation, which usually ran for several years, were passed on as before.

The initiated revival, which Möllmann recorded in a circular dated February 8, 1811, begins with the memory of the former director: “Many still remember the reading institute and the merits of the blessed school teacher Bernhard Foeth with touched gratitude, and it always is It is a pity that this good work did not survive in life as the good could no longer work. "

Incidentally, it is not surprising that the reading society was started by a former hirer and secondary school teacher. This profession had gradually developed from its originally direct dependence on the farms of the respective peasantry; In contrast to the angle schools run elsewhere and often despised , the secondary schools in Artland enjoyed great popularity and the hiring workers who had been promoted to teachers there assumed an increasingly respected position in the communities.

Objectives and procedures

For the early days of the reading society, as well as for the formation or the way in which the members found each other, little information has been preserved. On February 8, 1811, Möllmann summarized the target group of potential members on the occasion of the revival of the reading society as follows: “First I think of readers who have a mind and heart, which they enlighten, educate, ennoble, and make happy want to search. They are people, Christians, citizens, members of the empire of the world and want to be so with honor and dignity in their profession and class. "

He also wrote: “One must read in order to work, that is, to apply what has been read; so none of us should become inert in our professional duties by reading. Ora et labora; pray and work. We never want to forget reading and acting. "

Presumably as a result of the reception of relevant literature in the past, he expressed the task of the reading society more aggressively in 1829: "We also believe that we rural residents are just as good at being enlightened, refined and refined as other classes and world inhabitants!" And added added, which was one of the express goals over the entire period: “But we don't just want to read and not act. That would be wrong. Knowledge and action always go hand in hand. "

In line with the blossoming of national associations at that time, Möllmann explicitly called the reading society an association for the first time in 1829 and signed as director and member of the Menslager reading society . Despite significant changes in individual elements of the reading society in the course of time, the connection to the founding concept and the goals of the Enlightenment remained undiminished, as Möllmann's summary of 1829 shows: The purpose of our association was: “We wanted our spirit with the most necessary and the most useful knowledge of the earth and its inhabitants, of people, animals and spirits, of the arts and sciences, of agriculture and action, yes of religion and morality, etc. enrich and educate, refine and delight us more and more. "

Only three short regulations were recorded for the procedure and each of the future members accepted it with their signature. Since reasons and explanations for the specifications are missing in the minutes, the individual points must have been discussed orally beforehand - it cannot be determined whether it was not until 1811 or when it was founded in 1796. It was stipulated that every reader [should] have the right to propose a book according to reasons or to select some of the proposed and

- the contribution amount has to be made annually on a payment date to be determined.

Furthermore, book circulation and reading times were regulated: while magazines such as 'Der industrious and cheerful Wirthschaftsmann' should go like a newspaper ( i.e. circulate quickly), one should have a longer time for large books . After the set times, the literature was to be passed on, whether it was finished or not.

Members and membership development

The list of names begun in 1802 and extended to 1805, which is on the pages of the Christian Monthly, to strengthen and revitalize the Christian spirit , lists 38 people, some with their first names, some with a professional or professional title.

There is also the addition jfr. , Which obviously means maiden . Because of the different spellings, you can also choose between Fr. for "Friedrich" and fr. can be differentiated for "woman". This proves that women also belonged to the Menslager Reading Society, even unmarried ones (as indicated by the addition jfr. ) - a very unusual constellation, since otherwise women were usually excluded from reading associations even in the big cities.

It is also noticeable that in the course of the existence of the reading society almost all classes and many professions were represented: in addition to the dominant full and half-boys, teachers, hiring workers and markkotters, a baker, a carpenter, a carpenter, two merchants, a lieutenant, a Brewer, a Kirchhöfer, two musicians, an organist, a receptor, a watchmaker, a shoemaker, a geometer and of course a pastor. The other women identified were full heirs and Markköters and Heuermanns wives.

The note 2nd company on the mentioned list indicates that there must have been several simultaneous circulation lists. In his dissertation, Ziessow assumes that there were two such lists, each with the same number of people, and assumes that the first list also included 38 names, which means that "the actual number of participants in the circle was twice as large, including 76 people".

This conclusion, however, is neither logical nor reliable: theoretically there could have been any number of other lists and nothing has proven that the first list contained exactly as many names as the second. The actual number of addressees, and thus the number of members between 1802 and 1805, therefore remains in the dark; it is only proven that there must have been more than 38. Among other things, this combination error of Ziessow and the existence of a list of names dated February 9, 1811, which included 33 people with different names, is also due to his assumption that there were two different reading societies in Menslage. These conclusions cannot be drawn from the available documents, because the assertion that the second reading society was composed of other members cannot be supported because neither the number nor the names of all members could be proven. Rather, it is obvious that there was a reading society that had two leaders or initiators one after the other and that experienced a time-indefinable break-in after the death of the first leader. The fact that there is a distribution list from 1802 - one year after Foeth's death - which was handwritten by Möllmann, who had been a member of the reading society since it was founded, suggests that he - in the short or long term - after the early Tod Foeths took over the most important organizational work. Ziessow himself also writes: "In addition, the reading society led by Möllmann was only the revival of a previous institute ..." .

For the year 1820 there is a list of members that shows 51 people and one of 1829 with 32. In these later lists only the last names and occasionally first name abbreviations are entered, so that attempts to identify the respective persons individually would be mere conjectures. However, it is proven that between 1802 and 1805 four members of the reading association were women and in 1811 at least Ms. Ellerlage . Nevertheless, many members are known by name through these lists; often handed down details about their lives. Most of the information about the two directors and Bernhard Scherhage has been preserved, as information about them also appears in other archives.

Berend Foeth

The founder of the reading society, Berend Foeth (1756-1801), was born in the Hahlen peasantry as the son of the hayman Johann Hermann Foeth and Anna Catharina Lindemann, but "was later brought up by his uncle". It remains unclear whether his parents died early or they did not have the opportunity to raise their son. Possibly the unspecified "uncle" was a secondary schoolmaster in the Bottorf peasantry, where in 1822 a "teacher Hermann Gerhard Foeth" is proven.

Foeth learned the trade of a cooper , but has been recorded as a secondary school teacher in the Renslage peasantry since 1781 - although this is not a completely unusual career, as the teaching staff at angle and secondary schools were usually craftsmen, farmers and hirers. Immediately after Foeth took up his position, the teacher Ruwe complained because “the year passed ... only three children from the Renslage farmers went to the right school; This year there is not a lot going on, but the secondary schoolmaster has taken over from small to large under all sorts of pretexts. ” Since his income depends directly on the number of students who attended his school, he asked the consistory to give him for the children who did not attend his secondary school, but Foeth's secondary school, had to pay a third of the school fees as compensation. He was not granted this, but when it was decided that only children under the age of nine were allowed to attend secondary school, Foeth countered, “that under such circumstances [it] would be impossible for me to continue my otherwise meager school work and nourishment with it to have ” . For his part, Foeth asked for permission to “accept all children who are sent to me for information, without distinction, at least under one condition or another” . It is not known whether the dispute that had been smoldering for years between the main schoolmaster Ruwe and various secondary schoolmasters, which can be proven by documents in the Lower Saxony State Archives Osnabrück and in the archives of the Evangelical Lutheran parish of Menslage, ended with the allowance finally paid to Ruwe; the problem was solved in any case with Ruwe's death in 1784 at the latest, who was succeeded by the Renslager secondary schoolmaster Foeth with a certificate of employment dated March 26, 1784 as Menslage's secondary school teacher.

Foeth moved rent-free "a small vacant house without a garden" (the small cantor's house next to the tavern on a shared courtyard with the larger sexton's house) and in 1786 married Catharina Margaretha Klune. The marriage resulted in four sons, one of whom died in infancy. His wife died on June 16, 1793. The following year Foeth married again, Anna Margarethe Klune, presumably the sister of his first wife, with whom he had two more children.

In 1796 the schoolmaster founded the reading society, which in the course of its association's history had at times over 90 members - a pioneering act for Artland and the entire Osnabrück region, from which no other reading societies have come down to us at this time.

Foeth's enlightened teaching ("Through him the spirit of enlightenment pedagogy returned to Menslage also in the secondary school"), which found its way into the Menslager secondary school, has been reliably passed down, as is his conviction that the teaching profession is understood as a pedagogical mandate. Despite all the competition that prevailed between secondary and secondary school teachers, he worked together with Pastor Gerding on upgrading secondary schools, which was only implemented nationwide with the Hanover School Act of 1845. When Foeth died of “nervous fever” ( typhus ) on March 24, 1801 , the laborer's son, although he was denied higher administrative positions as a teacher, had a remarkable career and achieved a high position in the parish of Menslage. Pastor Gerding also mentioned in his obituary the reading society, which he owes.

Details about the organization of the reading society during this period are, however, only sparse. The practical founding initiative came from Foeth, and a large part of the content should also come from him. What literature was acquired and circulated, how the decisions were made and whether and where the members met is not known.

Bernhard Möllmann

Bernhard Möllmann (1760–1839) was born as the son of the landowner Johann Gerhard Möllmann and his wife Anna Margaretha Schechtmann on the Möllmannschen Hof in Klein Mimmelage. Möllmann attended the secondary school in Klein Mimmelage, followed by the secondary school in Menslage. He then received private tuition in Quakenbrück, only to be accepted into the local Latin school a year later, which he attended until 1778. The prorector of the grammar school in Lemgo , Stohlmann, who was previously the private tutor of the son of Pastor Gerding, who was almost the same age as Möllmann, and who recognized Möllmann's talent, enabled him to attend the Lemgo grammar school for three years. This was followed by studies of theology at the University of Göttingen from October 1781, which he finished in the summer of 1785.

Möllmann's schooling illustrates the social position of the peasantry in Artland at that time and what role education played. It is said that Möllmann's father died at an early age, but the widow was financially able, even interested in giving her son private lessons in the nearby town, followed by attending a distant high school and studying at a well-known university (A journey from Menslage via Osnabrück to Göttingen was arduous at this time and lasted several days, which is evident from a travel report by Möllmann's later Professor Lichtenberg, who traveled from Göttingen to Osnabrück in 1772).

Möllmann's first job was that of a private tutor with the Osnabrück Vice-Director Gruner, followed by a position as an adjunct with Pastor Neuschäfer in Melle . When the pastor died, he became the educator of the twin sons of Pastor Varenhorst in Bippen . In addition, he had the opportunity to preach in Bippen and Börstel every now and then . The fact that he was denied this in his home town may have been due to the fact that Gerding's son was now working as an adjunct to his father in Menslage.

On June 6, 1792 Möllmann and his "competitor" Johann Friedrich Arnold Gerding passed their exams after a trial sermon in the Marienkirche in Osnabrück. Gerding succeeded his father in Menslage and Möllmann became a preacher in the old monastery church of the free world monastery of Börstel . He held this pastoral position until 1810. From a list of the Abbess von Börstel, Charlotte Agnese von Dincklage, it can be seen that his income in this relatively small pastor's office was very modest with 291 Reichstalers, especially since this amount was a combination of shares in kind and money. With 518 Reichstalers , the Menslager Pfarre paid almost twice as much, which, in contrast to Möllmann, allowed Gerding to live a "befitting" country life.

Since the security of a permanent job enabled him to start a family regardless of the low budget, Möllmann married the sister of the new Menslager pastor, Catharina Rebecca Sophia Gerding, with whom he had six sons and a daughter. The young family led a withdrawn life in the sparsely populated parish of Börstel, which was in an unfavorable location to the economic centers of the north of Osnabrück. When Pastor Gerding died in 1810, at the age of only 48, of a "dangerous breast disease", Möllmann applied for the Menslager parish, where he had already represented his colleague for a long time due to his illness. He was sure of the support of the mayor ( maire ) Bonsack and the abbess of Börstel monastery, but resistance against him arose in the parish because he was already 50 years old, but also because he belonged to a local landowning family that was in dispute with some other families. A group of citizens of Menslager introduced the "Mr. Candidate Lange", the young headmaster of the Quakenbrück school. Möllmann, for his part, gathered other supporters around him, including his fellow student in Göttingen, Gustav Anton von Wolffradt , who is now Minister of the Interior of the Kingdom of Westphalia. During his correspondence with him, it turned out that Möllmann was the author of the anonymously published book Will mankind lose or gain through the secularization of the spiritual states in Germany? was. On the one hand, the book reflects Möllmann's broad general knowledge and his ability to absorb English and French specialist literature, and on the other hand, his interest in topics that mostly stem from non-theological areas such as history, regional studies, state theory or constitutional law. In the case of fragments of another script found in his estate with the title Can and must the human race not advance further in culture, must it stand still or even go backwards? Or about the consequences of mental freedom and mental compulsion. it remains unclear whether he ended it and whether it was published.

After several months of intrigues in the community, Möllmann was finally able to prevail and take the oath of office on July 4, 1810. He was engaged in a variety of tasks that were only partially official business. Outside of the spiritual area of responsibility, this included the supervision of the schools in the parish and a new division of the sexton and school service. But even in his time in Börstel he had already dealt intensively with the division of brands and had penetrated deeply into the disputes, which in turn also affected the teachers, who were all hunters and for whom he was particularly committed throughout his life.

As far as the documents indicate, his term of office was quite successful, in contrast to the recruitment procedure, even if there was a complaint that Konsistorialrat Martens from Osnabrück reached in 1825 and which he addressed to Superintendent Lange in Quakenbrück (the former teacher who was Möllmann's competitor in 1810 been around the pastorate was) passed on for consideration: " ... It has become known our collegium a rumor ... the pastor Mollmann in Menslage should treat public worship with a certain carelessness and the ordinances under forms that are not usually in our church and therefore are exposed to the impact. In particular, he is to distribute Holy Communion in such a way that the communicants stand in a row in front of the altar, to which he hands the bread, but another, who may not otherwise belong to the church servants, should carry the chalice and hand the wine. The sexton is supposed to count the communicants from the organ, tell Pastor Möllmann the number, and read this off immediately after the ordinance: 'So many have given me the confessional money; the rest of them still have to find their way. '” Lange wrote a brief, brief report in which he summarized that he had not found any complaints, so that the matter had no consequences for Möllmann.

Möllmann's wife died in 1819, and he did not remarry, perhaps because the most important reason for remarrying at the time was no longer taking care of children, his sons and daughter were already older. Möllmann's own provision for old age was presumably taken over by the family of his son Bernhard Jacob Gerhard Möllmann, who settled in the village as a merchant.

Möllmann, who had held office to the end, died at the age of 79. His personal book estate, insofar as it was preserved for his descendants, comprised predominantly theological literature, but non-theological works also played an important role here.

Bernhard Scherhage

Bernhard Scherhage, mentioned above, is another member of the reading society, about whom a lot has been passed down. In one of the Artländer court archives , the so-called Oing-Ellerlage court archives , there is a directory of books that the 19-year-old heir from 1820 to 1831 kept and in which he recorded over 100 books. In addition, lists in Scherhagen's estate show the existence of community subscriptions for Oldenburger and Hamburgische Blätter, which indicate, in addition to the reading society, other forms of organized reading in the parish that have not yet been researched and that some authors can combine, Scherhage was the first head of the reading society. However, this is not possible because he was born in 1801 and was first recorded in the reading society in 1820.

Scherhage, born on a full heir's farm in Klein Mimmelage and active as a representative of the peasant class at a young age, belonged to the Artländer peasant class that participated intensively in the intellectual life of the time. Despite his short life of barely 40 years, he left behind a library of over a hundred works and a large number of magazines, almost 1,000 pages of his own excerpting records from newspapers, magazines and books on numerous areas of knowledge.

A comparison of his literature with that of the reading society showed Ziessow that only a small part of the literature and literary knowledge available in the parish circulated through the reading society. For example, Scherhage and his administrator Schietert, who also had a library, had significantly more specialist agricultural literature.

Acquisition of literature, circulation, accounting

The main supplier of the books acquired for the reading society was the Hahn bookstore , now the Hahnsche Buchhandlung , in Hanover. She is the only one who Möllmann mentions by name in his notes and circulars: “Since the new books are to be paid for, which (I) already fetch, I have to pay the contribution owed to the reading society by November 1, 1829 at most ask that the Hahn brothers in Hanover and others like the bookbinder receive their money. "

Since it has been proven in the case of Scherhage that he received book shipments in the mail not only from Hahn, but also from Göttingen and Soest, this probably also applied to Möllmann. In addition, according to Ziessow, "in the parish itself there was a lively traffic of books that came close to urban level" . The fact that second-hand books were also purchased speaks for the books that were probably also acquired in the vicinity, as Möllmann wrote on May 8, 1813: “With the current selection, I was not able to deliver all the books properly, but most of them were. "

The most important shopping dates were around Easter (" Jubilate ", the third Sunday after Easter) and the end of September (" Michaelis " - short for September 29th), when the new goods were delivered from the Leipzig Book Fair. Möllmann warned repeatedly: "I will soon have to ask for payment for this 1811th year because the Michaelism Fair in Leipzig is approaching." However, books could increasingly be purchased throughout the year because the retail book trade had developed. So it was less about delivery dates than about paying for the goods: “Because the booksellers hold two book fairs, they like to ask for Jubilate and Michaelis money. So I must ask the fellow readers to support me around November 1st so that I can pay off the debt ” .

But not only books, but also magazines and newspapers were purchased or subscribed to, even if these, in contrast to many other contemporary reading societies examined, were of clearly secondary importance.

How the ordered books and magazines were sorted and distributed is determined by Möllmann's documentation of the first two deliveries he handled: The members had selected two works in advance. At the beginning of the “round trip”, each member received the books of their choice, in which Möllmann had entered the “travel route” in the front cover. At the same time, he documented the distribution in a circular containing information on the further procedure. The readers only entered the date of receipt in the circulation table and passed it on to the next recipient at an agreed latest time.

As further evidence that the Menslager Reading Society was not an instructive event for dignitaries, Ziessow evaluates the order of the readers, which is not based on a village ranking, but rather obviously on the traffic situation of the places of residence of the individual members. Möllmann also wrote in his circular dated September 13, 1811: "Because a few more books ... are easy to get, a few more readers could probably join them, especially where the readers are far apart, in order to make it easier for each other to send . "

The reading society had agreed on Sunday as the day to change books, because there would be more traffic on that day than on the other days - and this made it easier to pass the books on, for example when visiting church. In 1820 this form of personal transmission was abandoned: “From now on, my neighbor Diedrich Barlage [will] carry the books around. I ask you to give him the reading books so that he can bring them to his successor. "

Literature inventory

A comparison of the private literature of individual farms and persons recorded in the court archives with the literature of the reading society shows that only a small part of the literature and literary knowledge actually available in the parish circulated through the reading society. The works included in the already mentioned book directory of the heir of the court, Scherhage, range from beautiful literature with all of Schiller's works, Wieland or Bürger to philosophy with writings by Kant , works by Herder and Moses Mendelssohn, to other relevant theological or religious writings and encyclopedic literature of all Subjects to agricultural literature.

Due to the poor source situation from the time when Foeth headed the reading society, an investigation of the literary program of the reading society is only available for Pastor Möllmann's "term of office", ie from 1811 until his death. In his letter accompanying the founding circular of February 9, 1811, he dealt extensively with the question of the appropriate reading material ( but how can one set up this reading society so that the purpose of reading is not missed? ), While answering questions about the organization of the Society and the practical process only briefly touched on.

After general considerations: “… because that's how I think of books that… fit our region, our time, yes, for a popular society. Most of the readers are rural residents who want to read something that is useful to them. ” … “… Which books should one choose? This is extremely difficult among the thousands who are; partly because one can use little of the learned, scientific ones; partly because you have to look at the price, because not all readers can or will spend a lot of money. ... It seems to me that you only choose the next, the most suitable, to begin with, it may be old or new ... If there is more applause, you can also expand the plan. "He gave the organizational terms from which the literature should come:

- Anthropology, human history

- Description of the earth, astronomy, natural history, natural science

- World, state, human, peoples history

- Religion, morality

- Economy, housekeeping

- technology

- Pharmacy (cattle pharmacy)

What is interesting about this list of subject groups is the order. It did not follow the step from knowledge of God to knowledge of the world, which was still common in the times of the Enlightenment; however, the subject groups were not listed arbitrarily. Rather, contrary to the Church's proclamation, it began with human history. Religion is only in the fourth branch, which it also has to share with morality (which we now call morality). According to Ziessow, this structuring seems to be an "effect and propagation of that 'déchristianisation' through the work of the Enlightenment, against which an increasing resistance arose at the end of the 18th century" (He means the Reformations of German church history , including Pietism , Methodism and Awakening Movement ).

And finally, he listed a number of authors and titles to choose from among these subject groups. These specific literature suggestions, in turn, have the peculiarity of being thrown down almost fleetingly, of being predominantly incomplete in their titles and authors. In addition, he sometimes only named entire literary genres in summary form, for example biographies about Luther, Melanchthon, Zwingli, Calvin, Oedkolampad, Washington, Franklin, Spener, Möser, Jerusalem, Mosheim, Thoasius (in that order) without noting the authors or other book details. He also only mentions “Writings by Thaer and Riem” (meaning Albrecht Daniel Thaer and the bee researcher Johann Riem ) with the note “too expensive”, whereby the “too” was deleted (afterwards?).

From the nature of this list, Ziessow draws the conclusion that the addressee was a group of people who were not only used to dealing with written material, but also already knew the works and their authors - at least by name. Furthermore, he concludes from this that intensive personal communication between the members of the reading society is seldom directly verifiable from the sources.

When Möllmann presented the selection made by the reading society members on September 13, 1811, he made longer explanations about the further procedure and mentioned a possible assignment of the books to areas of interest, which offers an insight into the reading material, its structure and focus:

“For farmers, especially Leopolds, Boses, Pohls, Fischers, Hoffmanns and the writings on Fellenberg; Helmuth's writings also belong here. The artist finds Beckmanns Technologie pp .; the school man - parents - Funke, Frank, Salzmann, Spieker, Natorp, Meineke; the educator Salmann's Kiefer-, Ant- und Krebsbüchlein pp., Seiler. Nemnich, Humboldt, Krusenstern, Thieme, Rochow, Wilmsen, Wagner, Gelpke, Becker, Ziegenbein will serve to nourish and educate the mind and heart, to expand knowledge. "

From this it can be seen that modern subject areas did not play a role, but that utility and education were in the foreground. Nevertheless, Ziessow examined the title information on the list from February 1811 and, based on Möllmann's subject structure, assigned the titles, resulting in the following picture:

| Subject area | number |

|---|---|

| General knowledge | 24 |

| Agriculture | 14th |

| Art / craft | 3 |

| school | 4th |

| education | 2 |

| poetry | 3 |

| religion | 5 |

In another list, Ziessow gives an overview of the shifts that occurred in the literature between 1811 and 1829. In doing so, he does not use Möllmann's principles of division, but chooses a more precise division. The following picture emerges:

| Subject area | 9.2.1811 | 1811/1812 | 1813 | 1829 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| astronomy | 4th | 1 | - | 1 |

| poetry | 3 | - | - | 4th |

| History / politics | 5 | 7th | 5 | 4th |

| House book | 2 | - | - | - |

| Industry / craft | 2 | 2 | 1 | - |

| calendar | 4th | 2 | - | - |

| Agriculture | 1 | 6th | 1 | 2 |

| Reading book | 10 | 12 | 3 | - |

| Songbook | 3 | 4th | - | - |

| medicine | 1 | 3 | - | - |

| natural Science | 8th | 4th | 2 | 3 |

| pedagogy | - | 7th | 2 | 1 |

| philosophy | - | - | 1 | - |

| Travel reports | 5 | 3 | - | - |

| religion | 8th | 6th | 12 | 3 |

| Technique / technology | - | 1 | - | - |

| Magazines | 1 | 2 | 4th | 3 |

| total | 57 | 58 | 30th | 22nd |

The data for 1813 and 1829 do not have to be complete because they do not come from delivery lists or invoices, but rather from Möllmann's list in which he names the works that can be picked up from him.

Poetry and beautiful literature were of little importance in the Menslager literature program. Möllmann named only three Messiads , who were probably acquired because of their religious edification. However, one of them was Klopstock's Messiah , with whom, according to Madame de Staël, “the era of poetry in Germany began” (“C'est à la Messiade de Klopstock qu'il faut tixer l'èpoque de la poésie en Allemagne”).

Another peculiarity was the extensive lack of magazines, since otherwise periodicals are considered to be the most important foundation or even reason for founding reading societies. Jensch summed up that the reading society was originally an institution for reading newspapers at reduced prices; Prüsener agrees and dedicates a separate chapter heading to them (“Periodicals, the foundation of the library, as an answer to reader expectations”) and Milstein reports that books not only faded into the background, but were even rejected in individual cases. Möllmann named only one magazine in the holdings of the Menslager Reading Society: The hard-working and happy business man.

Reception of reading material

There are no studies of what effect the reading society had on thinking in the parish, but it was revealed, for example, in disputes about the successor to Pastor Möllmann as a political and social unit that understood itself on the basis of Enlightenment thinking. In August 1839, the month in which Möllmann had died, the provisional and peasant chiefs sent a long letter to the Osnabrück consistory in which they set out their ideas about a successor to the pastor.

Instructions for the reception of the reading material have only been handed down once - on the occasion of the second book shipment from 1813. Here Möllmann provided some works with references and remarks, apparently due to the increased difficulty of the literature. However, these comments did not suggest a specific interpretation of the content to the reader, but were suggestions for understanding the content or information about the author, such as: "Reimarus is the first man in natural religion along with Clarke, Wollaston and some others." ... " Niemeyer is a sure guide to the teachers and the parents. ”“ The Westphälische Magazin delivers for us Westphälinger. ” Only with the anecdotes about Frederick the Great did he warn against too much enthusiasm: “ The anecdotes of Frederick the One raise this great prince of spirit and heart; but all sayings are not gospels. Check everything and only keep the best! ” Since at least five accompanying circulars to book deliveries have been lost, it cannot be ruled out that Möllmann continued or even intensified his explanations, although nothing of this can be seen in the circulars from 1829 that have been preserved. At the reception of the scriptures, however, it was important to him to find out the interpretation of the members. This was expressed in a strong invitation to submit comments, which can be found in the documents several times, for the first time in 1811. Although he always insisted that the books be used carefully, kept clean and not soiled, he encouraged people to enter their opinions: “We read to increase our knowledge, to clear our minds, to train our hearts, to raise concerns . So I ask readers to write their comments in the back. If you find something good or faulty, wrong, etc., bring it to us others. "

This shows a decisive difference to most other reading societies, where as a rule any damage to the fonts had to be reimbursed and any notes in the books were strictly forbidden. For the Menslager Lesegesellschaft, the focus was not on maintaining the book value, but on the exchange of opinions and the "communication value of the medium" book as a consumer good.

Successor company and dissolution

There is no evidence of the dissolution of the Menslager Reading Society. With the death of Möllmann, however, a deep turning point arose and revealed a number of conflicts that initially led to the reading society continuing with gradual changes to previous practices, but the creeping and still growing dissatisfaction among the participants became so serious that it ultimately became one Cessation of the activity of the reading society.

Minutes of a general general meeting of 1840, shortly after Möllmann's death, contained complaints from members about the literary profile, especially the limited use of magazines during Möllmann's lifetime, and concerns about the association's indebtedness over the years. This report on the meeting also shows that there had been a regular board of directors for a long time, which should now be filled. The names of the elected board members were noted with their first letters; There were six people to judge by the abbreviations, Möllmann's son Bernhard Jacob Gerhard, born in 1802 (listed as Möllmann merchant ), the court owners Bentlage and Dürfeld (Katharina, who comes from this family, is mentioned under “Regional Background”) and Küster Pubke counted, with the latter apparently succeeding Möllmann in the management. The only personal data of Pubke that has come down to us is that he was a friend of Möllmann, came from Bippen , where he was a sexton and teacher and later became a sexton in Menslage, perhaps brought by Möllmann.

According to these minutes, the board of directors was instructed at the general meeting to “return the bill, to get the sale of the old books, in general everything useful for the society.” In the general assembly after this board election, however, Pubke challenged the election because “... nothing Written about it had been made, so it had no validity and the management of corporate affairs, at least in this year, was due to him alone. ”However, the board obviously did not want to support Pubke only, which he responded to with a written declaration in which he explained , "That he should release himself from society insofar as he leaves it to its own devices, but should also be jointly effective with advice and action for a prosperous continued existence." With this resignation of the clergyman, the last representative of the clergy withdrew, too if he later returned to the board. Ziessow sees this as "the significant structural step from parish association to political-cultural association". Ziessow also confirms this by the fact that Pubke writes in a letter to Bentlage dated April 17, 1846 that his "work, creation, work in all that time has been nothing, that the real sun must only rise now ..."

The conflict over Pubke also seems to have been a dispute with newly recruited members of the mountain parish, which was independent from 1839. In a letter from 1846, Pubke summed up: I can tell you frankly that the company passed brilliantly under my direction. This has come to me more than once and from several sources, even if Mr. Berger used other expressions. The Berger cost me a lot of money.

In addition, the fact that a reading institution was set up in Quakenbrück in 1844 may have played a role in the reduced interest in the reading society.

An entry in the notebook of the Menslager Kaufmann Möllmann, the son of Pastor Möllmann, shows that efforts to revive the reading group were made again in 1865 (whereby the choice of words “continue” indicates falling asleep rather than a temporary dissolution): “Menslage, 30 January 1865. The wish has already been expressed from so many sides to continue the local reading society, which has existed with such great success since the beginning of this century ... with rejuvenated and invigorating power. ... everyone who intends to take part is asked to come to the baker Bodemann's house next Saturday, February 4th, at 4 o'clock in the afternoon, to discuss the further. Möllmann. "

Numerous books in the holdings of the museum village of Cloppenburg as well as in private hands show that the effort was successful. Measured by the number of stamped books or books found with notes from the reading society, there must still have been broad participation in the reading society at the end of the 19th century.

A stamp made around 1850 was preserved (see illustration in the introduction); a last trace of the reading society, now more organized in the direction of a pure reading circle , can be found in the court files at Langhorst-Frese in Borg. In 1896, the court owner listed periodicals under the heading Menslage Reading Circle , which he apparently obtained for this association and circulated among the members. These were the magazines "Daheim", "Gartenlaube", "Landwirtschaftszeitung" and the "Landwirtschaftlich-Forstwirtschaftliche Vereinsblatt", some with supplements.

literature

- Bettina Busch-Geertsema : Miserable than in the poorest village? Elementary education and literacy in Bremen at the beginning of the 19th century. In: Hans Erich Bödeker, Ernst Hinrichs (Hrsg.): Literacy and literarization in Germany in the early modern period. Niemeyer 1999, ISBN 3-484-17526-5 .

- Otto Dann (ed.): Reading societies and bourgeois emancipation, a European comparison. CH Beck, 1981.

- Gerd Dethlefs , Jürgen Kloosterhuis (eds.): On a critical pilgrimage between Rhine and Weser: Justus Gruner's writings in the years of upheaval 1801–1803. Böhlau Verlag, Cologne / Weimar 2009, ISBN 978-3-412-20354-2 .

- Rolf Engelsing : The citizen as a reader, readers' story in Germany 1500-1800. Metzler 1974.

- Paul Goetsch : Reading and Writing in the 17th and 18th Centuries. Gunter Narr Verlag, 1994, ISBN 3-8233-4555-9 .

- Ernst Hinrichs : On research into literacy in northwest Germany in the early modern period. In: Anne Conrad (ed.): The people in the sights of the Enlightenment. Studies popularizing the Enlightenment in the late 18th century. LIT Verlag, Münster 1998, ISBN 3-8258-3100-0 , pp. 35-56.

- Georg Jäger , Alberto Martino and Reinhard Wittmann : The German Lending Library: History of a Literary Institution (1756-1914). O. Harrassowitz, 1990. ISBN 3-447-02996-X .

- Irene Jensch : On the history of newspaper reading in Germany at the end of the 18th century. Stein & Co., 1937.

- Barney M. Milstein : Eight eighteenth century reading societies. A sociological contribution to the history of German literature. Herbert Lang, 1972. ISBN 3-261-00753-2 .

- Marlies Prüsener : Reading Societies in the Eighteenth Century, A Contribution to Readers' History . Booksellers Association, 1972, ISBN 3-7657-0421-0 .

- Rudolf Schenda : People without a book, studies on the social history of popular reading materials 1770-1910. Vittorio Klostermann, 1988, ISBN 3-465-01836-2 .

- Bernd Sösemann : Communication and media in Prussia from the 16th to the 19th century. Franz Steiner Verlag, 2002, ISBN 3-515-08129-1 .

- Marlies Stützel-Prüsener : The German Reading Societies in the Age of Enlightenment. In: Otto Dann: Reading Societies and Bourgeois Emancipation, a European Comparison. CH Beck, 1981. pp. 71-86.

- Reinhard Wittmann : History of the German book trade. CH Beck, 1999, ISBN 3-406-42104-0 .

- Erich Wobbe : 800 years of Menslage in Artland. In: Heimat-Jahrbuch Osnabrücker Land. 1988, pp. 38-44.

- Karl-Heinz Ziessow : Rural reading culture in the 18th and 19th centuries. Museumsdorf Cloppenburg Foundation, 1992, ISBN 3-923675-13-5 .

Web links

- GWDG: Literacy and written culture in the early modern period.

- Martina Wiederrecht: Reading Societies in the 18th Century. (Script in computer-generated full text)

- Arnim Kaiser (Ed.): Sociable education. Studies and documents on adult education in the 18th century. (PDF file; 113 kB)

Individual evidence

- ^ Daniela Schmitt: Changes in reading behavior in the media society. GRIN Verlag, 2008, ISBN 3-640-23101-5 .

- ↑ Engelsing: The citizen as a reader. Pp. 183, 186.

- ^ German Historical Institute, Federal Ministry of Education and Science: Francia. Volume 25, part 2. Verlag Thorbecke, 1999. pp. 175 ff. ISBN 3-7995-7253-8

- ↑ Werner Besch, Anne Betten, Oskar Reichmann (Hrsg.): History of language: A manual for the history of the German language and its research. Verlag Walter de Gruyter, 2003, ISBN 3-11-015883-3 , p. 2404ff.

- ^ Wittmann: History of the German book trade. P. 189.

- ^ Peter Moraw: New German History. Volume 7. CH Beck, 1995, ISBN 3-406-30819-8 , pp. 214-215.

- ^ Anne Conrad (ed.): The people in the sights of the Enlightenment: Studies for the popularization of the Enlightenment in the late 18th century. Volume 1 of publications of the "Hamburg Working Group for Regional History". LIT Verlag, Münster 1998, ISBN 3-8258-3100-0 , p. 13.

- ↑ Holger Böning: The common man as an addressee of Enlightenment ideas. In: The Eighteenth Century. Volume 1. Wallstein Verlag, 1996, ISBN 3-89244-221-5 , p. 65.

- ^ Anne Conrad (ed.): The people in the sights of the Enlightenment: Studies for the popularization of the Enlightenment in the late 18th century. LIT Verlag, Münster 1998, ISBN 3-8258-3100-0 , p. 50.

- ↑ Irene Jentsch: On the history of newspaper reading in Germany at the end of the 18th century.

- ↑ Felicitas Marvinski: The Franconian Reading Society of 1795. In: Marginalien. Journal of book art and bibliophilia. 82 (1981), No. 2, pp. 63-83.

- ↑ Chronological Notes 2010 January ( Memento of the original from May 18, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ History of the Bülach Reading Society ( Memento of the original from July 29, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ For example, Barbara Weinmann: Another civil society. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2002. ISBN 3-525-35169-0 .

- ^ Hilmar Tilgner: Reading societies on the Moselle and Middle Rhine in the age of enlightened absolutism. Franz Steiner Verlag 2001. ISBN 978-3-515-06945-8 . P. 3

- ↑ Rhineland-Palatinate Bibliography

- ↑ Gerd Dethlefs , Jürgen Kloosterhuis (ed.): On critical pilgrimage between Rhine and Weser: Justus Gruner's writings in the years of upheaval 1801-1803.

- ↑ Gruner: On critical pilgrimage between the Rhine and Weser. P. 422.

- ↑ a b Gruner: On a critical pilgrimage between the Rhine and Weser. P. 429f.

- ↑ Museumsdorf Cloppenburg (ed.): The good room. Museumsdorf Cloppenburg, 2004. ISBN 3-923675-94-1 .

- ↑ Helmut Ottenjann : The silhouetteur Caspar Dilly. Family pictures of the rural population in western Lower Saxony 1805–1841. Heimatbund Oldenburger Münsterland, 1998, ISBN 3-9804494-9-1 .

- ↑ a b c Ziessow: Rural reading culture in the 18th and 19th centuries. P. 47

- ^ Museum village Cloppenburg: House and court archives of the rural population of Lower Saxony. Self-published by Museumsdorf Cloppenburg, 1991. p. 4.

- ↑ Peter von Polenz: German language history from the late Middle Ages to the present. Volume 2: 17th and 18th centuries. Verlag Walter de Gruyter, 1994, ISBN 3-11-013436-5 . P. 228.

- ^ Ziessow: Rural reading culture in the 18th and 19th centuries. P. 14.

- ^ A b Joachim Gessinger: About the connection between the acquisition of written language, the language system and the change in German induced by the written language. In: Jürgen Erfurt, Joachim Gessinger (Hrsg.): Osnabrücker contributions to language theory. 47. Oldenburg 1993, ISBN 3-924110-47-6 , p. 121.

- ^ The statistical handbook of the Kingdom of Hanover for the year 1848 shows 2685 inhabitants; other sources give 2800 for the early 18th century.

- ^ A b Helmut Ottenjann: On the building, economic and social structure of the Artland in the 18th and 19th centuries. Schuster Verlag 1979, ISBN 3-7963-0168-1 . P. 1.

- ↑ Erich Wobbe: 800 years of Menslage in Artland. In: Heimat-Jahrbuch Osnabrücker Land. 1988. p. 42.

- ^ Ziessow: Rural reading culture in the 18th and 19th centuries. P. 21

- ^ Kohnen: The origin of the name Art-Land. In: Osnabrücker Land. 1974, p. 49f.

- ^ Rolf Berner: Settlement, economic and social history of the Artland up to the end of the Middle Ages: A contribution to the history of the Osnabrück region. Series of publications of the Kreisheimatbund 1951. p. 96.

- ↑ Museumsdorf Cloppenburg ( Memento of the original from July 19, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Karl Döhmann: The book printers, bookbinders and booksellers of the academic high school in Burgsteinfurt. P. 90.