Mistivoy

Mstivoj († 990/995) from the family of nakonids was a elbslawischer Prince , who in the 10th century in what is now Mecklenburg and East Holstein over the tribal association of Abodrites prevailed.

After the death of his predecessor Nakon Mstivoj gained 965/967 dominion over the abodritischen stem, at least 967 the Samtherrschaft about the existing of several sub-tribes tribal confederation. Under Mistiwoj's Christian monarchical rule, a church organization in the Abodritic Empire was set up by the diocese of Oldenburg in Holstein, established around 972 . Mistiwoj maintained close relationships with the bishops and the princes of the neighboring Saxons and Danes , which he sought to secure through dynastic marriages. Although he was credited with participating in the Slav uprising and the destruction of Hamburg in 983 , Mistivoy lost large parts of his dominion to the victorious Lutizen as a result of the uprising . After a few months later in Quedlinburg, he initially sought the support of the Baierian aspirant to the throne, Heinrich the Quarrel, against the Lutizen, and until his death he proved to be an ally of the Roman-German King Otto III.

Only the more recent research on the history of the Abodrites classifies Mistivoy as "Slavic princes close to the empire" for the period after the Slavic uprising. In the depictions of the Ottonian Imperial Era, Mistivoy's role is still limited to the destruction of Hamburg and his participation in the Slav uprising of 983.

Life

Origin, family and name

Mistivoy is considered to be the son of the Abodritic prince Nakon . From the connection with an unnamed woman, Mistivoy had a son Mistislav . He achieved the dignity of velvet rulers around 990/995, but had to flee from a pagan uprising to Lüneburg in Saxony in 1018 . With the sister of the Oldenburg bishop Wago, Mistiwoj had a daughter Hodica , who later became the abbess of the nunnery on the Mecklenburg. The marriage to Wago's sister was later dissolved. Mistiwoj married another daughter, Tove , to the Danish King Harald Blauzahn before 987 . According to another opinion, it was not the daughter Tove who married the Danish king, but Mistivoy's widow, which, however, would require Mistivoy's death before 987. The Mistidrag / Mizzidrog passed down through Adam von Bremen could have been a brother of Mistiwoj.

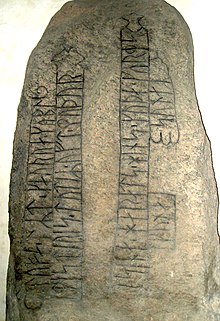

The name Mistiwoj comes from the Polish language and could have been Mstiwoj, in short Mstuj. It was a combination of the words m'stiti (= avenge) and woj (= warrior). The spelling Mistav , Mystuwoi and Mistui , Mystewoi , Mistiwoi and Mistwin can be found in the medieval Saxon written sources as onomatopoeic reproduction of the Polabian pronunciation . On the rune stone by Sønder Vissing, Mistiwoj is called Mistvir or Mistives , depending on how it is read .

As a baptismal name , Mistivoy could have received the name Billug after his possible godfather Hermann Billung .

Velvet rule

Mistivoy's monarchical-Christian rule over the Abodritic tribal association was based on an economically and militarily strong domestic power in the area of the Abodritic sub-tribe and a penetration of the Abodritic kingdom by a Christian church organization.

Rule over tribe and tribal association

After Nakon's death in 965/967, Mistivoy initially only took control of the sub-tribe of the Abodrites in the narrower sense. This settled in the area around today's Wismar and Schwerin . In the case of the Abodrites, the succession to the prince title was based on inheritance law. All male members of the ruling family held the title that was exercised by the oldest male representative (brotherhood). But the prince was not the sole representative of political will. Confirmation by a meeting of the nobility was required for the prince to be appointed as sovereign ruler over all sub-tribes. There is no evidence of such an act of legitimation for Mistivoy; in research, however, his sovereignty is considered secure.

Mistiwoj served as the central seat of power and representation of Mecklenburg . On or near the castle next to a the was Apostle Peter as patron consecrated church a nunnery. It served to center and consolidate the formation of rule, as a burial place and through prayer remembrance the identification of a family and clan as well as the representation of aristocratic rule. There the daughters of the nobles of the Abodritenland were taken in to bind the local noble families to the place of rule. The Mecklenburg was not intended for the Prince's permanent residence. Mistiwoj had to go there separately on the occasion of a visit by the Oldenburg bishop Wago. The existence of a chaplain could indicate a courtyard as an administrative facility and the entry of written form. Mistivoy's documents have not survived, however. There were other castles in Ilow and Schwerin .

In addition to these castles, armored horsemen provided additional support for the princely power. They are said to have been directly under Mistivoy's command. It is documented that the Abodritic warriors were armed with swords, helmets and chain mail in the year 965. The considerable means for equipping and maintaining this armed force came from the income from the princely property, in particular from the money levied on an agriculture that apparently produced an abundance of crops with two grain sows and remarkable horse breeding. In addition, coin finds in Arabic dirhams suggest income from long-distance trade, which could have been the slave trade.

In 967, Mistivoy won with a victory over Prince Selibur a loose suzerainty over the Abodritic sub-tribe of the Wagrians, who settled in Ostholstein, and thus the complete rule over the Abodritic tribal association. Connected to the sovereignty over the Wagrier was also that of the Polabians on both sides of the Ratzeburg Lake , which only appeared as a sub-tribe in the 11th century , and which for this time were still part of the Wagriers without their own princely house. In the east, the velvet rule extended to the sub-tribe of the Kessiner who lived along the Warnow around Bützow and Rostock . Even if the sources do not make any statements on this, it is now considered certain in research that Mistivoy's rule also included the sub-tribe of the Zirzipans on both sides of the upper Peene . In the south, the velvet rule extended along the Elbe to the Linonen tribe . In terms of content, Mistivoy's sovereign rule was limited to the collection of tributes from the sub-tribes and the leadership of the association contingent in the war. His claim to power related to the association of persons and not to a clearly defined territory. However, the Abodritic Empire, which was composed of sub-tribes, was already divided into a total of 18 castle districts. The castle districts were headed by, at least outside of the Abodritic sub-tribal area, indigenous noble families who had not received their power from Mistivoy, but instead invoked tribal inheritance law. At best, they served the respective tribal prince, whereby the scope of this service obligation can only be guessed at on the basis of news from later centuries.

The Abodritic Diocese

During the time of Mistiwoj's reign, the establishment of the first diocese in the area of the Abodritic tribal association fell with the establishment of the Oldenburg diocese in Holstein.

The initiative to found the diocese came from the Roman-German Emperor Otto I and was based on the contemporary model of the expansion of the Christian faith. In contrast, the will to incorporate Mistivoy's territory into the empire - if it existed at all - took a back seat. Nonetheless, the establishment of a Christian church organization in the area of the gentile religious abodrites meant an intervention in their social order and the existing power structures. This is why researchers agree that a successful development of the diocese against the will of Mistivoy can be ruled out, especially since Mistivoy's power would have prevented the permanent creation of ecclesiastical structures. It is even increasingly suggested that Mistivoy not only tolerated the establishment of the diocese, but actively promoted it. Various reasons are given for such funding. At first Mistivoy, like all Naconids, was a Christian. Thus, in accordance with the contemporary model, he was probably interested in the spread of the Christian faith. In addition to this personal conviction, there are also secular reasons for building a Christian church organization. Such administrative structures were suitable for spreading and enforcing the will to rule. In addition, Mistivoy might have intended to remove the legitimation of the pagan priesthood by proselytizing the tribe. This seems to have often found himself in opposition to the prince alongside a tribal nobility that was increasingly losing power.

The only traditional resistance to the establishment of the diocese did not come from Mistivoy, but from the ranks of the Church. The Hamburg-Bremen Archbishop Adaldag turned against the subordination of the Diocese of Oldenburg as a suffragan of the Archdiocese of Magdeburg on the basis of "older rights" that he claimed . Originally the emperor Oldenburg wanted to bundle like all other mission dioceses in Slavic territory in the archdiocese of Magdeburg. Ultimately, however, Otto I had to consent and when it was founded, the Abodritic diocese was subordinate to the Archdiocese of Hamburg-Bremen.

Why the choice of the bishopric did not fall on the Mecklenburg as the central seat of power Mistiwojs, but on the Vagrian prince castle Starigard / Oldenburg, does not emerge from the sources. It is true that the Vagrian dynasty had already adopted the Christian faith before the diocese was founded. Excavations on the Oldenburg unearthed Christian body graves and remains of church buildings from the 950s. The mission of the Vagrian dynasty was probably carried out by the Schleswig Bishop Marco at the instigation of the Archdiocese of Hamburg. However, the conversion of the first Nakonid velvet ruler went back to the year 931. In addition, large parts of the Abodritic population and the lower nobility in both sub-tribal areas equally adhered to the pagan tribal belief, so that even at the royal courts, Christian religion and pagan tribal belief were practiced side by side.

Erich Hoffmann thinks it is conceivable that Oldenburg, because of its location "on the edge" of the Abodrite Empire, was given preference over the Mecklenburg, so that the bishopric could also serve as a military outpost of the Empire in the hostile Abodrite area. Jürgen Petersohn, on the other hand, thinks that Mistiwoj had "independent ideas about the church organization and allocation of the area he ruled" and therefore initially preferred to see the bishopric on the Oldenburg.

The structure of the church organization initially made good progress. There is no record of resistance from the population for religious or cultural reasons. In addition to several male and female monasteries, a parish church system was created that was based on the Abodritic administrative districts with their aristocratic castles. Christian churches are said to have existed in 15 out of 18 of these administrative districts. In the first phase, churches and monasteries were given the right to raise taxes from farmers within the administrative district, which were measured according to the yield. This practice soon seems to have given rise to disputes because it led to an additional tax burden on farmers. Mistiwoj then agreed with the Oldenburg Bishop Wago that the taxes would be replaced by the transfer of lands and villages to the churches, although it remains unclear whether this agreement should be general or only apply to selected farms. However, this regulation does not seem to have found general recognition either, especially since it may have curtailed the wealth of the lower nobility. In any case, there were frequent attacks on church property afterwards.

Saxon relations

Mistivoy had close ties with the Saxon noble family of Billungers . During the reign of Mistiwoj, with Hermann Billung and his son Bernhard I, these were the outstanding leaders in north-eastern Saxony, with Bernhard I at least holding the office of duke in Saxony. Historians report on the specifics of the Saxon-abodritischen relations Widukind of Corvey and Thietmar of Merseburg from Saxon perspective unanimously Mstivoj was the Bill Ungern as a vassal to pay tribute and military service was required. With the siege of Starigard Castle in 967, the Battle of Danewerk in 974 and the Italian campaign in 982, three joint military ventures can be identified.

Siege of Starigard

In 967, Mistiwoj and Hermann Billung besieged a castle located on Slavic territory together with their troops. It was very likely the Vagrian main castle Starigard. The initiative to siege Starigard may have come from Mistivoy. Although he was able to take over the rule in the Abodritenland unhindered, he was confronted with a revolt of the local nobility in Wagrien . There the Wagrians under their Prince Selibur tried to seize the opportunity and break away from the Abodritic tribal association. To stop the separatist tendencies, Mistivoy marched with an army in front of Selibur's castle. After Mistiwoj had closed the siege ring, Hermann Billung arrived there with his troops and joined the siege on Mistivoy's side, especially since Selibur had allied himself with Hermann's "arch enemy" Wichmann II . While Wichmann II managed to escape from the castle with his closest confidants, Selibur, who was completely unprepared for a siege, had to surrender after a short time. The castle was looted and Selibur was ousted. His son Sederich , brought in by Hermann from Saxony, took control of Wagrien, but recognized the sovereignty of Mistivoy. Hermann punished the Saxon companions of Wichmann II who remained in the castle, without anything being reported about sanctions against the Wagrians.

In Widukind's history of Saxony, the uprising of the Wagrians was directed not against the supremacy of Mistiwoj, but against that of Hermann Billung. As the chief judge, he had previously decided a dispute between Mistiwoj and Selibur to the disadvantage of Selibur, whereupon Selibur rebelled against Hermann Billung. However, this perspective of Widukind is considered wrong by many researchers, since the siege of Starigard Castle was started by Mistivoy himself, according to Widukind's own remarks. In addition, the dispute between the two Slavic princes was primarily an internal Abodritic matter.

Battle of the Danewerk

In autumn 974, Emperor Otto II undertook a campaign against the Danish ruler Harald Blauzahn , who had invaded northern Albingia in the summer and devastated the country with fire and sword. Together with the Saxon Duke Bernhard I and Heinrich von Stade , the emperor then set out north from Frohse at the head of an imperial army . In addition to the Saxons, Franks and Frisians, the Imperial Army also had a Slavic division. Neither the Saxon nor the Danish sources provide information about their origins and the person of their leader. Nevertheless, it is assumed in research that the Slavs were Abodrites under the leadership of Mistivoy. Their settlement area bordered in Wagrien both on that of the Danes and on that of the northern Albingians. In addition, Mistiwoj owed the Saxon Duke Bernhard I army successes. Ultimately, the empire used ships that were decisive for the war: after the imperial army had initially unsuccessfully overran the Danish protective wall, the Danewerk, which was defended by the Norwegian Håkon Jarl , the attackers, according to a plan by Bernhard I, took ships across the Schlei and circumvented the Danish defense lines in this way. Since the Reichsheer did not carry any ships with them overland and the Frisians who were experienced in sea warfare had their ships lying on the North Sea coast, the use of the Abodritic fleet would at least be obvious.

Italian campaign

In 981, the East Frankish-German King Otto II began his preparations in Italy for an attack against the Saracens , who had advanced from Sicily to the southern Italian mainland under the leadership of their Emir Abu al-Qasim . For this campaign, he requested an additional 2090 armored riders in the northern part of the empire for support. Although Saxon nobles are not mentioned in the written draft notice, Bernhard I was apparently also supposed to send a contingent. He seems to have turned to Mistivoy in the course of the evictions. Berhard's I request possibly went beyond the army succession owed, be it due to the scope or the deployment in southern Italy. Because Mistivoy demanded, in return for the participation of his warriors, the marriage of his son Mistislaw to a niece of Bernhard I and thus a dynastic union of the two royal houses. Bernhard I promised to get married on his return from Italy, whereupon Mistivoy allegedly provided a thousand horsemen under the leadership of his son Mistislaw. Even if the proportions are immeasurably exaggerated, it must have been a remarkable delegation of Abodritic warriors by medieval standards, who traveled alongside Bernhard I over the Alps to northern Italy. While Bernhard I had to return early to the north due to an incursion by the Danes, almost all Abodrites in Italy were killed. Even if nothing precise is known about their specific fate, they should take part in the battle of Cape Colonna , in which the imperial army was defeated.

Mistiwoj's son Mistislaw returned to Mecklenburg with the few survivors. But when he demanded the fulfillment of the marriage promise, the bride was denied him by Count Dietrich von Haldensleben with the words that one should not give a duke's blood relatives to a dog. Apparently Bernhard I was not present when this insult was uttered, because according to Helmold he sent messengers to Mistivoy at a later date with the news that he would keep the promise made. Mistivoy refused, however, and is said to have stated that the dog would bite hard when it was big. Dietrich von Haldensleben's motives for his resistance against a dynastic union of Billungers and Nakoniden were probably mostly of a power-political nature. With Bernhard I as well as Mistivoy he competed as Margrave of the North Mark for influence in the Slavic areas. In particular, the sovereignty over the tribal areas of the Zirzipans, which were traditionally subject to the Abodritic claim to power and whose settlement area also belonged to the Diocese of Oldenburg, could have been controversial between Mistiwoj and the Billungern on the one hand and Margrave Dietrich von Haldensleben on the other.

In contrast, Dietrich von Haldensleben's ethnic reservations about a marriage between the Slavic prince's son and the Saxon princess can be ruled out. Such connections were not unusual. Dietrich himself had sponsored a marriage between his eldest daughter Oda and the Polish prince Mieszko I in 978 , and his further daughter Matilde had married the Hebrew prince Pribislaw. Mistivoy was married to the sister of the Oldenburg bishop Wago, and a relative of the Saxon Duke Bernhard I, Weldrud, had been given to the Wagrian prince Sederich as a wife.

Decline

Mistivoy's political decline began with the Slav uprising of 983 . In the east, the sub-tribes of the Zirzipans and Kessiner fell from him one after the other and joined the Lutizen , who were victorious in the Slav uprising . In the west, the Wagrians began to return to their pagan tribal beliefs. In response to the threat to his Christian monarchical rule from the pagan alliance of Lutizen, Mistivoy sought reference to the Roman-German Emperor and the Eastern Franconian Empire. After the Diocese of Oldenburg perished in an uprising by the Wagrians in 990, the episcopal seat was moved to Mistiwoj's central seat on the Mecklenburg in 992. If Mistivoy was still alive in 995, the demonstrative visit of the Roman-German Emperor Otto III was meant. on the Mecklenburg in early September 995 a strengthening of Mistivoy's unstable political position.

Slavic uprising of 983

The Slav uprising of 983 represented an uprising of the Slavic tribes united in the Lutizenbund against the tribute rule of Margrave Dietrich von Haldensleben. On June 29, 983, the Lutizen first destroyed the bishopric in Havelberg and three days later conquered the Margrave's seat with the Brandenburg . This destroyed imperial rule east of the Elbe for decades.

According to the prevailing opinion, Mistiwoj is said to have participated in the uprising on the part of the Lutizen by devastating northern Albingia, cremating Hamburg , destroying the Oldenburg diocese and finally destroying the Benedictine monastery in Kalbe (Milde) far south of his dominion in the Altmark . A passage from the Slav chronicle by the chronicler Helmold von Bosau , written 200 years after the events, is cited as evidence of Mistivoy's participation in the Lutizen uprising . After that, Mistivoy visited the tribal shrine of the Lutizen in Rethra immediately before the uprising , in order to report to the tribes gathered there of the serious insult by Dietrich von Haldensleben. At the request of the Lutizen he swore off the Saxons. Then Helmold describes Mistivoy's extermination campaign. In contrast, in research on the history of the Abodrites, concerns have always been expressed about Mistivoy's participation in the Slavic uprising in 983, as this cannot be reconciled with his policies before and after the uprising.

- Destruction of Hamburg

However, around 40 years after the Slavic uprising in connection with the Slavic attacks on Havelberg and Brandenburg, the historian Thietmar von Merseburg had already stated that Mistiwoj had burned down and devastated the bishopric in Hamburg. However, there are doubts as to whether the attack on Hamburg coincided with the Lutizen uprising in 983. The representation of Mistivoy's attack on Hamburg in the context of the Slav uprising does not necessarily have to describe two simultaneous events, especially since Thietmar did not intend to represent the Slav uprising. Rather, he was interested in enumerating all the attacks against Christianity that followed the, in his opinion, illegal dissolution of the diocese of Merseburg in 981. In addition, after a later comment by Thietmar, Mistiwoj is said to have gone mad about his actions, so that he had to be kept on a chain. In 984, however, according to Thietmar's report, Mistiwoj took part in Heinrich the quarrel's Easter court day in Quedlinburg - and apparently with good senses. And in Hamburg, the episcopal documentary activity did not cease until around the year 1014, which would have been expected earlier if the bishopric had been laid waste. In none of the contemporary annals and chronicles is a Slavic attack on Hamburg noted for the year 983. In contrast, Adam von Bremen clearly reports in his Hamburg church history of the devastation of northern Albingia and the destruction of Hamburg by the Abodrites, which took place after 983, possibly even under Mistivoy's son Mistislaw in 1012.

- Attack on Kalbe

Mistivoy's attack on the monastery of Kalbe, dedicated to St. Lawrence, is also controversial. Thietmar von Merseburg only explains that there was an attack on the monastery, but not who attacked it. The Magdeburg archbishopric from the 11th century and the Magdeburg annals from the 12th century are much clearer. Both explicitly name Mistivoy and the Abodrites as attackers. However, since it cannot be ruled out that the authors used Thietmar's text as a template and edited it according to their own ideas, usually only Thietmar's text is used as evidence. In it the mad Mistivoy complains that St. Lawrence would burn him, which has been interpreted as a punishment by the saint for the destruction of the Laurentius monastery in Kalbe. That Laurentius was at the same time the patron saint of the dissolved diocese of Merseburg and that Mistivoy could have sinned against it in an unknown way remains unreasonable. Another connection between Mistiwoj and the Kalbe monastery is established via Oda von Haldensleben. The daughter of Margrave Dietrich von Haldensleben was a nun in the monastery of Kalbe until her marriage to Miesko I in 978. Thus, five years after Oda's departure, Dietrich von Haldensleben was no longer able to destroy the monastery and is therefore rather ruled out as a target of retaliation for Mistivoy’s serious insult to his son by Dietrich von Haldensleben.

- consequences

The pagan-alliance "state idea" of the Lutizen exerted a great attraction on the Abodritic tribes, which threatened the continued existence of the Abodritic empire and thus Mistivoy's Christian monarchical rule.

In the east, Mistivoy first lost control of the zirzipans immediately adjacent to the Lutizen, which joined the victorious Lutizen League. Mistivoy's power must also be visibly eroded in the area of the Kessiner, because at an unknown point in time after 983 they split off from the tribal association and from then on belonged to the lutician core tribes for almost 100 years.

In the west, after 983, the Wagrians began to return to pagan tribal belief. This process is likely to have been accompanied by a gradual loss of Mistivoy's supremacy over the Wagrian sub-tribe. It is possible that Mistiwoj founded the marriage between his daughter Tove and the Danish King Harald Blauzahn in this context, in order to revive the traditionally good relations with the Danes and to forge a new alliance against the Vagrian sub-tribe and to isolate them between the Danes, Abodrites and Saxons.

An additional worsening of the situation is likely to have resulted from the loss of the Abodritic Italian contingent and the associated loss of military strength, quite apart from the social tensions that arose in the population through the death of a large number of warriors by medieval standards becomes.

Based on the realm

During this crisis, Mistivoy was looking for a strong ally. It therefore appeared in the spring of 984 on the Easter day of the crown applicant Heinrich der Zänker in Quedlinburg, Saxony. There Mistivoy recognized his claim to the royal dignity and thus passed over the underage heir to the throne Otto III. This partisanship, however, was not directed against Otto III, but was motivated by the hope of military support from a politically capable and powerful ruler against the threat from Lutica. Since, besides Mistiwoj, the other two Christian monarchical Slavic princes, the Polish Duke Mieszko I and the Bohemian ruler Boleslav II , swore their support to Heinrich as the future king at the court day, it is assumed that Heinrich formed an alliance against these three West Slavic princes the Lutizen agreed, especially since at least Mieszko I. was in a situation comparable to that of Mistivoy due to the Lutizen uprising.

However, while Mieszko I and Boleslav II due to their presence on the Easter day of the child king Otto III. publicly displayed their loyalty to the rightful king in Quedlinburg in 996, there is no evidence of Mistivoy's presence there. In contrast to Mieszko I., there is also no news about Mistivoy's participation in the Saxon campaigns against the Lutizi in 985, 986 and 987. Nevertheless, recent research assumes that Mistivoy continued to belong to the Slavic princes who were close to the empire. There is no other explanation for the relocation of the abodritic bishop's seat from Oldenburg to Mecklenburg in 992. The bishopric on the Oldenburg was lost in 990. In the course of a religiously motivated uprising, the Wagrians destroyed St. John's Church, killed numerous clergy under cruel torture and expelled the incumbent Bishop Folkward. If the Christian church organization in Wagrien collapsed completely, it apparently remained untouched in the Abodritenland. The Archdiocese of Hamburg - Bremen stuck to its suffragan bishopric and ordained Reinbert, a titular bishop for the Diocese of Oldenburg. As part of a canonical provisional arrangement, this took on the mediation of Count Lothar III. von Walbeck his diocesan seat at least temporarily on the Mecklenburg. This relocation is said to have been specifically supported by Mistivoy, who had promised himself the creation of a sacred space that was more independent from the imperial church.

In the late summer of 995, the Roman-German King Otto III. with a large army through the Abodritenland over the Mecklenburg into the tribal area of the Lutizen. The king's stay on the Mecklenburg served as a demonstrative strengthening of the Christian Naconid rulers against internal and external resistance and was the king's first visit to a residence of a Slavic prince. It is not clear whether this prince was still Mistivoy or whether the friendship visit by the king even occurred on the occasion of Mistislav's appointment as successor to his father Mistivoy. The year of Mistivoy's death has not been recorded. Because documents of the Abodritic diocese, insofar as they survived the uprising of the Wagrians in 990, were destroyed at the latest on the occasion of the expulsion of Mistislaw by the Lutizians in 1018.

Aftermath

Mistiwoj already achieved historical authenticity in the history of Saxony of the Benedictine monk Widukind von Corvey, which was written from 967 and is thus contemporary. Widukind describes Mistiwoj rather casually as a conspicuously independent vassal of Hermann Billung. For Thietmar von Merseburg, who in his chronicle written between 1012 and 1018 for the year 984 highlights Miesko of Poland and Boleslaw II of Bohemia from a number of unnamed Slavic princes, Mistivoy was one of the most important Christian Slavic princes of his time. In contrast, Mistiwoj encounters Adam von Bremen in the Hamburg church history, written around 1070, primarily as an apostate and peacemaker. Adam von Bremen sometimes confuses Mistiwoj and his son Mistislaw. This error continues with Helmold von Bosau, whose Slav story is largely based on the news of Adam von Bremen. 200 years after Mistivoy's death, Helmold paints a very differentiated picture of Mistivoy, who finally turned away from Billungers and Christianity. Mistiwoj becomes an enemy of the Saxons and Christianity at about the same time in the Chronicle of the Annalista Saxo .

swell

- Paul Hirsch , Hans-Eberhard Lohmann (ed.): Widukindi monachi Corbeiensis rerum gestarum Saxonicarum libri tres. Hanover 1935 ( MGH Scriptores rerum Germanicarum in usum scholarum separatim editi, volume 60). Digitized

- The chronicle of Bishop Thietmar von Merseburg and her Korveier revision. Thietmari Merseburgensis episcopi chronicon. Edited by Robert Holtzmann . Berlin 1935. (Monumenta Germaniae Historica. Scriptores. 6, Scriptores rerum Germanicarum, Nova Series; 9) Digitized

- Adam of Bremen : Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum . In: Werner Trillmich , Rudolf Buchner (Hrsg.): Sources of the 9th and 11th centuries on the history of the Hamburg Church and the Empire. = Fontes saeculorum noni et undecimi historiam ecclesiae Hammaburgensis necnon imperii illustrantes (= selected sources on German history in the Middle Ages. Freiherr-vom-Stein-Gedächtnisausgabe. Vol. 11). 7th edition, expanded compared to the 6th by a supplement by Volker Scior. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2000, ISBN 3-534-00602-X , pp. 137-499.

- Helmold : Slawenchronik = Helmoldi Presbyteri Bozoviensis Chronica Slavorum (= selected sources on German history in the Middle Ages. Freiherr-vom-Stein-Gedächtnisausgabe. Vol. 19, ISSN 0067-0650 ). Retransmitted and explained by Heinz Stoob . Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1963 (2nd, improved edition. Ibid 1973, ISBN 3-534-00175-3 ).

literature

- Bernhard Friedmann: Investigations into the history of the abodritic principality up to the end of the 10th century (= Eastern European studies of the state of Hesse. Series 1: Giessen treatises on agricultural and economic research in the European East. Vol. 197). Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1986, ISBN 3-428-05886-0 .

- Jürgen Petersohn: King Otto III. and the Slavs on the Baltic Sea, Oder and Elbe around the year 995. Mecklenburgzug - Slavnikid massacre - Meißen privilege. In: Early Medieval Studies . Vol. 37, 2003, ISSN 0071-9706 , pp. 99-139, digital version (PDF; 2.98 MB ).

Web links

Remarks

- ^ Peter Donat : Mecklenburg and Oldenburg in the 8th to 10th centuries. In: Mecklenburgische Jahrbücher. Vol. 110, 1995, pp. 5-20 here p. 13; Nils Rühberg: Obodritische velvet rulers and Saxon imperial power from the middle of the 10th century to the elevation of the principality of Mecklenburg in 1167. In: Mecklenburgische Jahrbücher. Vol. 110, 1995, ISSN 0930-8229 , pp. 21-50, here p. 22; Wolfgang H. Fritze: Problems of the abodritic tribal and imperial constitution and its development from a tribal state to a ruling state. In: Herbert Ludat (ed.): Settlement and constitution of the Slavs between the Elbe, Saale and Oder. W. Schmitz, Gießen 1960, p. 141–219 here p. 159, critical of the descent Helge bei der Wieden : The beginnings of the house of Mecklenburg - wish and reality. In: Yearbook for the history of Central and Eastern Germany . Vol. 53, 2007, pp. 1-20, here p. 5 f. with the note that this has not been proven by sources.

- ↑ After Franz Boll : About the Obotrite Prince Mistuwoi. In: Yearbooks of the Association for Mecklenburg History and Archeology, Vol. 18. Schwerin 1853, pp. 160–175, here p. 173 a "Wendish wife."

- ↑ Helmold I, 13-15.

- ↑ Christian Lübke: The Relationships between Elbe and Baltic Sea Slavs and Danes from the 9th to the 12th Century: Another Option of Elbe Slavic History? in: Ole Harck, Christian Lübke (Ed.): Between Reric and Bornhöved. Steiner, Stuttgart 2001, pp. 23–36, here p. 31 assumes 967 as the year of marriage without further explanation.

- ^ Birgit and Peter Sawyer: A Gormless History? The jelling dynasty reviseted. In: Wilhelm Heizmann, Astrid van Nahl (ed.): Runica - Germanica - Mediaevalia. De Gruyter, Berlin, New York 2003, pp. 689–706, here p. 702, against this expressly Marie Stoklund: Article Sønder Vissing. In: Heinrich Beck, Dieter Geuenich, Heiko Steuer (Hrsg.): Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde. Volume 29. De Gruyter, Berlin, New York 2005. A marriage of Harald Blauzahn with Mistiwoj's abandoned wife (Wago's sister) is not considered by either of them.

- ↑ Wolfgang H. Fritze : Problems of the abodritic tribal and imperial constitution and its development from a tribal state to a ruling state. In: Herbert Ludat (ed.): Settlement and constitution of the Slavs between the Elbe, Saale and Oder. W. Schmitz, Gießen 1960, pp. 141-219, here p. 157, note 125.

- ^ Christian Lübke : Eastern Europe. Siedler, Munich 2004 p. 532.

- ↑ Widukind III, 68.

- ↑ Thietmar III, 18 and II, 14.

- ↑ Adam II, 40.

- ↑ Helmold I, 16.

- ↑ Chronicle of the Lüneburg Michaeliskloster a. A. 1001.

- ^ Birgit and Peter Sawyer: A Gormless History? The jelling dynasty reviseted. in: Wilhelm Heizmann, Astrid van Nahl (eds.): Runica - Germanica - Mediaevalia. DeGruyter, Berlin, New York 2003, pp. 689-706, here p. 702.

- ^ For equating Mistiwoj and Billug Gerd Althoff : Saxony and the Elbe Slavs in the Tenth Century. In: The New Cambridge Medieval History . Volume 3: Timothy Reuter (Ed.): C. 900 - c.1024 Cambridge University Press, Cambridge et al. 1999, ISBN 0-521-36447-7 , pp. 267-292, here p. 283.

- ↑ Ruth Bork: The Billunger. With contributions to the history of the German-Wendish border area in the 10th and 11th centuries. Greifswald 1951, p. 26; following her Bernhard Friedmann: Studies on the history of the Abodritic Principality up to the end of the 10th century (= Eastern European Studies of the State of Hesse. Series 1: Giessen Treatises on Agricultural and Economic Research in the European East. Vol. 197). Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1986, ISBN 3-428-05886-0 , p. 244.

- ↑ Wolfgang H. Fritze: Problems of the abodritic tribal and imperial constitution and its development from a tribal state to a ruling state. In: Herbert Ludat (ed.): Settlement and constitution of the Slavs between the Elbe, Saale and Oder. W. Schmitz, Gießen 1960, pp. 141-219 here SS 184; Klaus Zernack specifically follows him : Abodriten. In: Herbert Jankuhn , Heinrich Beck et al. (Hrsg.): Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde. Volume 1: Aachen - Bajuwaren. 2nd, completely revised and greatly expanded edition. de Gruyter, Berlin et al. 1974, ISBN 3-11-004897-3 , pp. 13–15, here p. 13.

- ↑ Irene Crusius

- ↑ Jürgen Petersohn: King Otto III. and the Slavs on the Baltic Sea, Oder and Elbe around the year 995. Mecklenburgzug - Slavnikid massacre - Meißen privilege. In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 37, 2003, ISSN 0071-9706 , pp. 99-139, here p. 111.

- ↑ Helmold I, 15.

- ↑ Thietmar IV 2 mentions a chaplain; Gerd Althoff: Saxony and the Elbe Slavs in the Tenth Century. In: The New Cambridge Medieval History. Volume 3: Timothy Reuter (Ed.): C. 900 - c.1024 Cambridge University Press, Cambridge et al. 1999, pp. 267–292, here p. 283, Mistiwoj grants an “entourage”, ie an entourage.

- ↑ Wolfgang H. Fritze: Problems of the abodritic tribal and imperial constitution and its development from a tribal state to a ruling state. In: Herbert Ludat (ed.): Settlement and constitution of the Slavs between the Elbe, Saale and Oder. W. Schmitz, Gießen 1960, pp. 141–219, here p. 197.

- ^ Report of Ibrahim ibn Yaqub , printed by Georg Jacob : Arab reports from envoys to Germanic royal courts from the 9th and 10th centuries . In: Viktor v. Geramb , Lutz Mackensen: Sources for German folklore. , Vol. 1, DeGruyter, Berlin, Leipzig 1927, pp. 11-18, here p. 11.

- ^ Matthias Hardt: Long-Distance Trade and Subsistence Economy. Reflections on the economic history of the early Western Slavs. in: Uwe Ludwig, Thomas Schilp (eds.): Nomen et Fraternitas. Festschrift for Dieter Geuenich on his 65th birthday. De Gruyter. Berlin, New York 2008, pp. 741-764, here p. 753; Wolfgang H. Fritze: Problems of the abodritic tribal and imperial constitution and its development from a tribal state to a ruling state. In: Herbert Ludat (ed.): Settlement and constitution of the Slavs between the Elbe, Saale and Oder. W. Schmitz, Gießen 1960, pp. 141-219 here p. 196f.

- ^ On the long-distance trade in slaves among the Western Slaves Matthias Hardt: Long-distance trade and subsistence economy. Reflections on the economic history of the early Western Slavs. in: Uwe Ludwig, Thomas Schilp (eds.): Nomen et Fraternitas. Festschrift for Dieter Geuenich on his 65th birthday. De Gruyter. Berlin, New York 2008, pp. 741-764, here pp. 747-749.

- ↑ Gerard Labuda : On the structure of the Slavic tribes in the Mark Brandenburg (10th-12th centuries). In: Yearbook for the History of Central and Eastern Germany Vol. 42 (1994) pp. 103-140, here pp. 129 f.

- ^ Christian Lübke : Between Poland and the Empire. Elbe Slavs and Gentile Religion . In: Michael Borgolte (ed.): Poland and Germany 1000 years ago. The Berlin conference on the "Gnesen Act". Academy. Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-05-003749-0 , pp. 91–110, here p. 97.

- ↑ On the dating around 972 Helmut Beumann : The establishment of the Diocese of Oldenburg and the mission policy of Otto the Elder. Size In: Horst Fuhrmann, Hans Eberhard Mayer, Klaus Wriedt (eds.): From the history of the empire and the history of the north. (Karl Jordan on his 65th birthday) (= Kiel historical studies. Vol. 16). Klett, Stuttgart 1972, ISBN 3-12-902710-6 , pp. 54-69, whose work marks the state of research to this day.

- ↑ Hagen Keller : The "legacy" of Otto the Great. In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 41, 2008, pp. 43-74, here p. 52.

- ↑ Hagen Keller: The "legacy" of Otto the Great. In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 41, 2008, pp. 43-74 here p. 53; Hermann Kamp : Violence and Mission: The Elbe and Baltic Sea Slavs in the crosshairs of the empire and the Saxons from the 10th to the 12th century. In: Christoph Stiegerman, Martin Kroker, Wolfgang Walter (Eds.): Credo. Christianization of Europe in the Middle Ages. Volume 1: Essays. Imhof, Petersberg 2013, ISBN 978-3-86568-827-9 , pp. 395-404, pp. 396, 398.

- ↑ Jürgen Petersohn: The southern Baltic region in the ecclesiastical-political power play of the empire, Poland and Denmark from the 10th to the 13th century. Mission, church organization, cult politics . Böhlau, Cologne et al. 1979, p. 21 initially assumed only a “certain agreement” between the Hamburg Archbishop Adaldag and the Abodritic ruler, represented in Jürgen Petersohn: King Otto III. and the Slavs on the Baltic Sea, Oder and Elbe around the year 995. Mecklenburgzug - Slavnikid massacre - Meißen privilege. In: Early Medieval Studies . Vol. 37, 2003, ISSN 0071-9706 , pp. 99-139 here p. 111 but already the view that Mistivoy promoted the establishment of the diocese; Christian Lübke : Between Poland and the Reich. Elbe Slavs and Gentile Religion . In: Michael Borgolte (ed.): Poland and Germany 1000 years ago. The Berlin conference on the "Gnesen Act". Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-05-003749-0 , pp. 91–110, here p. 97 means that the Abodritic velvet ruler had “come to terms” with the Saxons in this regard; Nils Rühberg: Obodritische velvet rulers and Saxon imperial power from the middle of the 10th century to the elevation of the principality of Mecklenburg in 1167. In: Christa Cordshagen: Mecklenburgische Jahrbücher. Bd. 110, Schwerin 1995 pp. 21–50, here p. 23 according to Mistivoy "promoted" the establishment of the diocese.

- ↑ Adam I, 43.

- ↑ Erich Hoffmann: Contributions to the history of the Obotrites at the time of the Naconids. In: Eckhard Hübner, Ekkerhard Klug, Jan Kusber (eds.): Between Christianization and Europeanization. Contributions to the history of Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages and early modern times. Festschrift for Peter Nitsche on his 65th birthday (= sources and studies on the history of Eastern Europe. Vol. 51). Steiner, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-515-07266-7 , pp. 23–51, here p. 27.

- ↑ Jürgen Petersohn : The southern Baltic region in the ecclesiastical-political power play of the empire, Poland and Denmark from the 10th to the 13th century. Mission, church organization, cult politics (= East Central Europe in the past and present. Vol. 17). Böhlau, Cologne et al. 1979, ISBN 3-412-04577-2 , p. 21.

- ↑ Ingo Gabriel: The King of Wagrien and golden reliquary pouch. in: Ralf Bleile (ed.): Magical shine. Gold from archaeological collections in Northern Germany Schleswig 2006, pp. 144–155; following him Michael Müller-Wille : Between Starigard / Oldenburg and Novgorod. Contributions to the archeology of West and East Slav areas in the early Middle Ages. (= Studies on the settlement history and archeology of the Baltic Sea regions. Vol. 10). Wachholtz, Neumünster 2011, ISBN 978-3-529-01399-7 , p. 26.

- ↑ Jürgen Petersohn: The southern Baltic region in the ecclesiastical-political power play of the empire, Poland and Denmark from the 10th to the 13th century. Mission, church organization, cult politics (= East Central Europe in the past and present. Vol. 17). Böhlau, Cologne et al. 1979, ISBN 3-412-04577-2 , p. 21.

- ↑ Annales Augienses 931: Henricus rex reges Abodritorum et Nordmannorum effecit christianos , also the Annales Hildesheimenses 931, in addition Bernhard Friedmann: Studies on the history of the Abodritic principality up to the end of the 10th century (= Eastern European studies of the State of Hesse. Series 1: Giessener Abhandlungen zur Agricultural and economic research of the European East. Vol. 197). Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1986, ISBN 3-428-05886-0 , pp. 183-185.

- ↑ Erich Hoffmann: Contributions to the history of the Obotrites at the time of the Naconids. In: Eckhard Hübner, Ekkerhard Klug, Jan Kusber (eds.): Between Christianization and Europeanization. Contributions to the history of Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages and early modern times. Festschrift for Peter Nitsche on his 65th birthday (= sources and studies on the history of Eastern Europe. Vol. 51). Steiner, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-515-07266-7 , pp. 23–51, here p. 30.

- ↑ Jürgen Petersohn: The southern Baltic region in the ecclesiastical-political power play of the empire, Poland and Denmark from the 10th to the 13th century. Mission, church organization, cult politics . Böhlau, Cologne et al. 1979, p. 21.

- ↑ Comprehensive on "Saxon politics" Mistiwojs Bernhard Friedmann: Studies on the history of the Abodritic Principality up to the end of the 10th century (= East European Studies of the State of Hesse. Series 1: Giessener Abhandlungen zur Agrar- und Wirtschaftsforschung der European Ost. Vol. 197). Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1986, ISBN 3-428-05886-0 , pp. 241-259.

- ↑ Widukind III, 68

- ^ Christian Lübke: Eastern Europe. Siedler, Munich 2004 p. 181 interprets Hermann Billung's arrival as targeted support for Mistiwoj.

- ↑ Wolfgang H. Fritze: Problems of the abodritic tribal and imperial constitution and its development from a tribal state to a ruling state. In: Herbert Ludat (ed.): Settlement and constitution of the Slavs between the Elbe, Saale and Oder. W. Schmitz, Gießen 1960, pp. 141–219 here p. 159; Peter Donat: Mecklenburg and Oldenburg in the 8th to 10th centuries. In: Mecklenburgische Jahrbücher. Vol. 110, 1995, pp. 5-20 here p. 17.

- ↑ Gunter Müller: Harald Gormssons royal fate in pagan and Christian interpretation. in: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 7 (1973), pp. 118-142, here p. 124.

- ↑ Bernhard Friedmann: Studies on the history of the Abodritic principality up to the end of the 10th century. (= East European Studies of the State of Hesse. Series 1: Giessen Treatises on Agricultural and Economic Research in Eastern Europe. Vol. 197 ). Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1986, ISBN 3-428-05886-0 , pp. 177, 243; so also Wagner, Wendenzeit pp. 40, 85 f .; before him Giesebrecht.

- ↑ Adam von Bremen, II, 43, Scholion 21, p. 218.

- ↑ This is the assessment made by Erich Hoffmann: Contributions to the history of the Obotrites at the time of the Naconids. In: Eckhard Hübner, Ekkerhard Klug, Jan Kusber (eds.): Between Christianization and Europeanization. Contributions to the history of Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages and early modern times. Festschrift for Peter Nitsche on his 65th birthday (= sources and studies on the history of Eastern Europe. Vol. 51). Steiner, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-515-07266-7 , pp. 23–51, here p. 26.

- ↑ Thietmar III, 24.

- ↑ This is what Peter Donat suspects: Mecklenburg and Oldenburg in the 8th to 10th centuries. In: Mecklenburgische Jahrbücher. Vol. 110, 1995, pp. 5-20 here p. 18.

- ↑ Bernhard Friedmann: Studies on the history of the Abodritic principality up to the end of the 10th century. (= East European Studies of the State of Hesse. Series 1: Giessen Treatises on Agricultural and Economic Research in Eastern Europe. Vol. 197). Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1986, ISBN 3-428-05886-0 , p. 241.

- ↑ For a split of the eastern sub-tribes as a result of the Slav uprising Gerard Labuda: On the structure of the Slavic tribes in the Mark Brandenburg (10th-12th centuries) In: Yearbook for the history of Central and East Germany vol. 42 (1994) p. 103 -140, here p. 134; Bernhard Friedmann: Studies on the history of the abodritic principality up to the end of the 10th century. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1986, pp. 270 and 272 emphasizes the successive nature of this detachment process.

- ↑ Jürgen Petersohn: King Otto III. and the Slavs on the Baltic Sea, Oder and Elbe around the year 995. Mecklenburgzug - Slavnikid massacre - Meißen privilege. In: Early Medieval Studies . Vol. 37, 2003, ISSN 0071-9706 , pp. 99-139, here p. 111.

- ↑ The dating of the corresponding passages in Adam von Bremen II, 41 and II, 43 is highly controversial and varies between 983 and 1018. The prevailing opinion now assumes 990: Hermann Kamp : Violence and Mission: The Elbe and Baltic Sea Slavs in the crosshairs of the empire and the Saxons from the 10th to the 12th century. In: Christoph Stiegerman, Martin Kroker, Wolfgang Walter (Eds.): Credo. Christianization of Europe in the Middle Ages. Volume 1: Essays. Imhof, Petersberg 2013, ISBN 978-3-86568-827-9 , pp. 395-404, here p. 398; Bernhard Friedmann: Studies on the history of the Abodritic Principality up to the end of the 10th century (= Eastern European Studies of the State of Hesse. Series 1: Giessener Abhandlungen zur Agrar- und Wirtschaftsforschung der European Ost. Vol. 137). Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1986, ISBN 3-428-05886-0 , p. 267; Introduction to the dispute with Fred Ruchhöft: From the Slavic tribal area to the German bailiwick. The development of the territories in Ostholstein, Lauenburg, Mecklenburg and Western Pomerania in the Middle Ages (= archeology and history in the Baltic Sea area. Vol. 4). Leidorf, Rahden (Westfalen) 2008, ISBN 978-3-89646-464-4 , pp. 124–128, especially p. 127. Erich Hoffmann takes a different view : Contributions to the history of the Obotrites at the time of the Naconids. In: Eckhard Hübner, Ekkerhard Klug, Jan Kusber (eds.): Between Christianization and Europeanization. Contributions to the history of Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages and early modern times. Festschrift for Peter Nitsche on his 65th birthday (= sources and studies on the history of Eastern Europe. Vol. 51). Steiner, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-515-07266-7 , pp. 23–51, here p. 31 (in the year 1018).

- ↑ Gerd Althoff / Hagen Keller: The time of the Ottonians. From the Eastern Franconian Empire to the Roman-German Empire 888-1024. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2008, p. 269.

- ↑ Helmold II, 16.

- ↑ Fundamental Gerard Labuda: On the structure of the Slavic tribes in the Mark Brandenburg (10th-12th centuries) In: Yearbook for the history of Central and East Germany Vol. 42 (1994) pp. 103-140, here pp. 133f.

- ↑ Thietmar III, 18.

- ↑ Kerstin Schulmeyer-Ahl: The beginning of the end of the Ottonians. Constitutional conditions of historiographic news in the Chronicle of Thietmar von Merseburg. DeGruyter, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-11-019100-4 , p. 247; similarly already the interpretation by Lorenz Weinrich : The Slavs uprising of 983 in the representation of the Bishop Thietmar von Merseburg , in: Dieter Berg / Hans-Werner Goetz (Ed.): Historiographia Mediaevalis. Studies of historiography and source studies of the Middle Ages. Festschrift for Franz-Josef Schmale on his 65th birthday. Darmstadt 1988, pp. 77-87, here p. 84.

- ↑ Fred Ruchhöft: From the Slavic tribal area to the German bailiwick. The development of the territories in Ostholstein, Lauenburg, Mecklenburg and Western Pomerania in the Middle Ages. (= Archeology and history in the Baltic Sea region. Vol. 4). Leidorf, Rahden (Westphalia) 2008, ISBN 978-3-89646-464-4 , p. 126 f.

- ↑ For a gradual separation of the eastern sub-tribes as a result of the Slav uprising Bernhard Friedmann: Investigations into the history of the Abodritic principality up to the end of the 10th century. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1986, pp. 270 and 272.

- ↑ Bernhard Friedmann: Studies on the history of the Abodritic principality up to the end of the 10th century. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1986, p. 267 states that Mistiwoj's control over the Wagrians had "loosened considerably by 990."

- ↑ On the family connections of the Nakoniden with the Danish royal house Christian Lübke: The relations between Elbe and Baltic Sea Slavs and Danes from the 9th to the 12th century in: Ole Harck, Christian Lübke (Hrsg.): Between Reric and Bornhöved: the relationships between the Danes and their Slavic neighbors from the 9th to the 13th century: Contributions to an international conference, Leipzig, 4th-6th centuries December 1997 , Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 2001, pp. 23–36, here p. 31.

- ↑ Thietmar IV, 9.

- ↑ Jürgen Petersohn: King Otto III. and the Slavs on the Baltic Sea, Oder and Elbe around the year 995. Mecklenburgzug - Slavnikid massacre - Meißen privilege. In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 37, 2003, ISSN 0071-9706 , pp. 99-139 here p. 111.

- ^ Knut Görich : German-Polish relations in the 10th century from the point of view of Saxon sources. in: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 44, 2010 pp. 315-325, here p. 318; Jürgen Petersohn: King Otto III. and the Slavs on the Baltic Sea, Oder and Elbe around the year 995. Mecklenburgzug - Slavnikid massacre - Meißen privilege. In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 37, 2003, ISSN 0071-9706 , pp. 99-139 here p. 111 f.

- ↑ Widukind III, 68

- ↑ Annalista Saxo 983: Postea vero Mistowi dux Abdritorum et sui monasterium sancti Laurentii martiris, in urbe que Calvo dicitur situm, desolantes, nostros sicuti fugaces cervos insequebantur.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Mistivoy |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Mistui; Mistewoi; Mistuwoi |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Velvet ruler of the Abodrites |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 10th century |

| DATE OF DEATH | 990 or 995 |