Nestor cup

Nestor's cup is the name of the mythical Nestor's mixing cup from Pylos , as Homer described it in the Iliad . The Greek name for the vessel is Νεστορίς ("Nestoris"). Because the Iliad poet gives little and unclear information about the appearance of the beaker, it was discussed extensively in ancient times. The mythical Nestoris was also the namesake for a double-handled, Italian vase type from the fifth and fourth centuries BC. In the Middle Ages and modern times, too, the Nestoris employed philologists such as Eustathios and writers such as Andrea Alciato or Friedrich Schiller equally. In 1876 Heinrich Schliemann found a gold cup in Mycenae , the shape of which is similar to that described by Homer; he therefore believed that he had found the real example of Nestoris.

A “Nestor cup” is also the name given to a drinking vessel discovered in 1954 on the island of Ischia with an inscription that relates to Nestor and his cup. Whether it alludes to the Nestor cup of the Iliad or the Nestor of the epic cycle is still controversial. The inscription is nevertheless of great historical importance because it is one of the earliest datable Greek inscriptions in alphabet form. Since the characters already differ significantly from the Phoenician ones, it can be concluded that the alphabet must have been adopted some time before the inscription was added.

The iliadic Nestor cup

The cup in the Iliad

In the eleventh book of the Homeric Iliad, verses 632–637, a mixing vessel is described that Nestor brought from Pylos with him to the Trojan War . It is on the table in Nestor's tent with honey, barley flour and a basket of onions:

πὰρ δὲ δέπας περικαλλές, ὃ οἴκοθεν ἦγ 'ὁ γεραιός,

χρυσείοις ἥλοισι πεπαρμένον · οὔατα δ' αὐτοῦ

τέσσερ 'ἔσαν, .DELTA..di-elect cons πελειάδες ἀμφὶς ἕκαστον δοιαὶ

χρύσειαι νεμέθοντο, δύω δ' ὑπὸ πυθμένες ἦσαν.

ἄλλος μὲν μογέων ἀποκινήσασκε τραπέζης

πλεῖον ἐόν, Νέστωρ δ 'ὁ γέρων ἀμογητεὶ ἄειρεν.

(according to the edition by Martin L. West )

... plus the extremely beautiful cup that the old man brought from home,

studded with golden nails, and had

four ears , and two pigeons pecked on either side

of each one, golden ones, and two legs were under it.

Everyone else moved it with difficulty from the table,

when it was full, but Nestor, the old man, lifted it without difficulty.

(Translation: Wolfgang Schadewaldt )

Hekamede, a servant of Nestor from Tenedos , fills the goblet with pramnian wine and sprinkles white barley and grated goat cheese over it. Nestor and Machaon , wounded in the right shoulder, drink this kykeon , whom Nestor had driven from the battlefield to take care of him.

The cup in the ancient Homer discussion

Although Homer dedicates six verses to Nestoris, her picture remains strikingly vague compared to that of other objects described in the Homeric epic. Therefore, the appearance of the Nestoris was widely and extensively discussed in ancient times. The Homerscholien testify to Aristonikos , Didymos , Herodian , Ptolemaios from Askalon , Stesimbrotos and further, anonymous scholars who dealt with the Nestor cup; in addition, Athenaios quotes in the 11th book of the Deipnosophistai Aristarchus and Asklepiades von Myrleia from his lost work About Nestoris . Asklepiades and Athenaios himself name other people who are said to have dealt with the cup: Dionysios Thrax (who is also said to have tried to replicate it in silver), Apelles , Promathidas from Herakleia and Sosibios from Sparta . Further sources of the Nestoris discussion are Porphyrios ' Iliad Scholien as well as the Iliad commentary of Eustathios from the 12th century.

In the Hellenistic Homer philology two schools stood opposite one another, the Alexandrian and the Pergamene ; the former was mainly concerned with the appearance of the cup, the latter with its allegorical meaning. Some of the ancient and medieval suggestions on how to imagine Nestoris are as follows:

- Studded with golden nails (v. 633)

- The Iliad writer uses the same words to describe the staff of Achilles (1, 245-246); Golden nails also shine on the sword hilt of Agamemnon (11-29 / 30). It is evidently decorative elements in the form of short rivets with large heads and not, as Apelles said, according to Asklepiades, humps that were punched out of the cup from below with a graver and only looked like nails. This would be all the more implausible as all ancient commentators, including Eustathius, assumed that the cup itself was made of silver: “For if the cup had been solid gold, why should he (Homer) have pointed out that the nails and the rock doves? were golden if it had been made entirely of gold? ”(Eustathios) In principle, however, other materials such as bronze, wood or (elven) bone can also be considered.

- He had four ears (v. 633-634)

- οὔατα ( úata ) would be more aptly translated with “handle” instead of “ears”. Aristarchus imagines them to be arranged in pairs in the form of a small omega , but makes no statement as to whether he imagines them to be horizontal or vertical. So you would have to reach into the handle from below or from the side to drink. Apelles, on the other hand, assumes two vertical, openwork handles, which are divided into two struts in the middle, so that only the impression arises that there are four.

- two pillars were among them (v. 635)

- Tradition creates difficulties here. Three variants were discussed in antiquity, of which only the first two are attested:

- ὑπὸ πυθμένες is the best documented reading and is also based on Schadewaldt's translation. ὑπὸ ( hypò "below, below") and ἦσαν ( êsan "were") are then in Tmesis ; the half verse is translated: "and two feet were under". It is questionable, however, why the cup should have had two feet and whether πυθμένες could not also mean floors or lateral supports ; in general it probably means the lowest part . Athenaios mentions three interpretations for two feet: Either the first, smaller foot belonged to the body, the second was attached to it so that both merged into one another. Or the foot that widened towards the bottom had a second, smaller one; in both cases it remains open why Homer should have spoken of two feet, although only one was visible. Finally, two feet that are actually independent of one another would be possible, the use of which would again be unclear.

- ὑποπυθμένες is preferred by the Pergamene interpreters. The word resulting from this summary would be an adjective that is nowhere else attested and should be read as an epithet of the "doves" mentioned in the previous verse. The passage would then be translated: "... and two (more pigeons) were at the bottom of the feet."

- ὑπὸ πυθμένες ' would mark the failure of a dative iota with the apostrophe , so the πυθμένες would be in the dative. The half verse would read: "... and two (more pigeons) were under the feet", whereby the phrase "under the feet" would not make the passage easier to understand.

- Everyone else moved it with difficulty from the table, / when it was full, but Nestor, the old man, lifted it without any effort. (V. 636/637)

- Taken literally, these verses sound paradoxical: “Of course, the mixing cup for Achilles or Aias would not have been difficult to lift.” (Eustathios) This also applies when you consider that it is not a small drinking cup, but a large mixing vessel. The ancient Homer discussion made five different suggestions on this point:

- Most often the opinion was expressed that the lines should actually be understood as praise to Nestor, even if only as a formula with no deeper meaning. The modern approach of Arne Furumark , Klaus Rüter and Barbara Patzek , to interpret the statement in a similar way to the one that only Odysseus can draw his bow, fits this (see below ). Athenaios claims, however, that for this statement the indefinite pronoun τις ( tis “any”) must add the word ἄλλος ( állos “other”) to “some other”.

- The possibility that ἄλλος had a krasis , that this word actually meant, ἄλλος ( ho állos “the other”) and was only contracted to ἄλλος , was also much discussed . It would also be possible that the passage reads ἀλλ 'ὃς (μογέων) ( all' hòs mogéon "the (struggling) but"). The other meant Machaon, who was injured on the right shoulder and therefore could not lift anything heavy. However, it would have been questionable “praise” for Nestor to be stronger than an injured person. In addition, the last mention of Machaon is already 23 verses back at this point, so that the reference seems quite constructed. It is also not very good grammatically: The first variant is ruled out because it should have been ὥλλος as early as the 8th century . The second variant is also grammatically incorrect; the article ὁ ( ho "der") drawn from the participle could not be replaced by the relative pronoun ὅς ( hós "which").

- Because of the strange shape of the mug, it might take some practice to pick it up; Only its long-term owner succeeded immediately.

- According to Porphyrios, Antisthenes points out that Nestor was the most hard-drinking of the heroes before Troy and so did not get drunk. He probably meant that Nestor was the last person at the feast who could still lift the cup when everyone else was no longer able to do so.

- Sosibios (after Porphyrios already Aristotle ) proposed to read ὁ γέρων ( ho géron "the old man") in v. 637 as a koinon of an Apokoinu ; it would then refer not only to Νέστωρ (Nestor), but also to ἄλλος ( állos “other (r)”) in the previous verse. The two verses would mean: "Every other old man (!) Moved him with difficulty from the table when it was full, but Nestor, the old man, lifted him without difficulty." - because Nestor was still very vigorous for an old man .

All in all it must be stated that the ancient commentators did not succeed in giving a satisfactory and coherent explanation of all the elements of Nestoris.

Athenaios narrates an allegorical interpretation of Nestoris des Asklepiades, which is obviously inspired by the mastermind of the Pergamene school Krates von Mallos . Asklepiades sees in the Nestor cup an imitation of the spherical shape of the cosmos. The golden rivets or humps symbolize the stars - which would stand out particularly well on a silver background (see above) -, the doves ( πελειάδες peleiádes ) literally symbolize the seven stars , the Pleiades . Two of them sit on each pair of handles and two “support” the chalice, which makes a total of six: In the sky you can actually only see six of the seven Pleiades. Hence the reading of v. 635b preferred by the Pergamenern, which deviates from the one preferred today (see above). The Pleiades as mythical figures stand for sowing and harvesting, so ultimately for food. While in the myth they bring ambrosia to Zeus , in the Iliad they “carry” wine to the king's mouth. According to Asklepiades, “the ancients” also designed other objects in the shape of circles or spheres and provided round loaves of bread with stars in order to adapt what was around them to the cosmic forms.

Modern views on Nestoris

All modern approaches to the Nestor cup have in common that the question of the exact shape of the Nestoris does not take up much space. This is certainly due, among other things, to the fact that this fulfills no further function within the Iliad than that it is ascribed to the aged Nestor as an attribute, similar to the Agamemnon his scepter or, in other works, to Heracles his club. How exactly the Nestoris may have looked is therefore irrelevant. The cup symbolizes the traits of the old man: his pleasure in drinking and, due to the tongue loosing itself while drinking, chatty and persuasive skills. The attempt to gain power over one's counterpart by means of rhetoric plays an important role in the Homeric feast. According to Furumark and Patzek, the fact that Nestor alone can lift the cup when it is full can therefore be seen parallel to the particularly effective weapons of the Aristien such as the bow of Odysseus, which only he can draw : the device, in this case the symbolic " Weapon “the art of persuasion, only obeys its owner.

Erich Neu pointed out the close relationship between the word δέπας ( dépas "cup") and the hieroglyphic Luwian word tipas , which means heaven . In an ancient Ethite script, a basin is reported in which two "skies" lie - one made of iron, one made of copper - and nine nails, and which is used by the royal couple to hold the water for the mouthwash. It is now assumed that the “heaven” were hollow bodies in which the nails were located. Such “heavens” had roughly the shape of the Luwian glyph for tipas with the same meaning. A Middle Hittite ritual script fragment mentions a "sky made from half a handful of flour, with stars worked into it" - this is reminiscent of Asklepiades' claim that "the ancients" made sacrificial cakes decorated with stars, which they called moons . The images of partially four-handled δέπα on the pylostite tablets , which are referred to as dipa in Linear B , no longer resemble heavens, but this may be due to a shift in meaning . If it is true that δέπας came from Hittite via Luwian into Mycenaean and Greek , Homer's use of Depas could be interpreted as a reflection of the original meaning of the term, which had already faded in Mycenaean times, which denoted a significantly larger vessel than the drinking cup of the Depas type was. This view strengthens Marinatos' assumption that the four handles are actually offset by 90 ° to each other. The οὔατα were not taken while drinking, but to hold the mixing vessel and move it.

The "Nestor Cup" from Mycenae

Heinrich Schliemann visited the early historical ruins of Mycenae for the first time in 1869. In contrast to others, he was looking for the burial place of Agamemnon not outside, but inside the castle walls. He started the excavations in 1876. In grave IV Schliemann finally found a golden cup that reminded him of the Nestor cup from the Iliad.

The mug is almost 14 cm high and is made entirely of sheet gold. The body is formed by a 7 cm high and a maximum of 9 cm wide truncated cone with an unusually sharp upper edge, which is closed at the bottom by a wide disc and rests on a wide cylinder as a foot. Two diametrically opposite, flat straps serve as handle supports, which are divided into three struts over almost the entire length and may have been attached later (see below). In the middle there is a larger recess so that the supports only appear to be open at these points. The gold ribbons are riveted onto the presumably actual Vaphio -type handles with gold nails (named after the laconic place where many cups of this type were found, see picture). Where the upper part of the Vaphio handle is attached to the body, sit two birds with outspread wings and inward-facing, compact bodies, without a neck, a very thick and crooked head and a long, straight tail. The bottom of the cup consists of two thin sheets of metal, the first of which curves upwards so that the bottom is hollow. Therefore the straps could only be fixed there with a thin pin.

The gold cup is now in the National Archaeological Museum of Athens .

Reference to the iliadic Nestor cup

On closer inspection, the cup has little to do with the King of Pylos . On the one hand, it is dated to 1600 BC. Dated during the Trojan War (if at all) in the 13th or 12th century BC. Has taken place. The cup would have been buried for several hundred years at the time of the war. Almost all the elements of Nestoris that Schliemann believed he could recognize in "his" cup are not present in the gold cup, as has been clear since Furumark's 1946 essay at the latest. The number of handles (two instead of four) and birds (one instead of two on each handle) do not match. The nails on the Mycenae cup are not used for jewelry and are hidden so that they would hardly have been considered in a description of the cup. The material of the cup itself and the number of feet may also differ. In addition, the birds on the gold cup are evidently not pigeons at all, since, according to the ancient logic of the picture, they were never depicted as birds of flight with outstretched wings, but sitting or walking like swimming birds. Rather, the shape of the birds suggests that they are falcons; therefore the mere fact that the Nestoris, like the gold cup from Mycenae, have birds on their handles, would be a common feature. Birds, however, were a popular decorative element in Cypriot cups as early as the 3rd millennium BC. Chr.

Spyridon Marinatos argued that the birds on the gold cup from Mycenae were Horus falcons. Like Fritz Schachermeyr , Marinatos assumed that the Mycenaean princes had defeated the Egyptians in the battle against the 1700 BC. He supported the Hyksos invading Egypt and brought back gold from this war, but also cultural stimuli. This could also be indicated by the fact that there are no other known drinking cups with bird decorations in the Greek settlement area apart from the Schliemann cup, even if there are many different types of such decorated vessels. In addition, Mycenaean vessels are never decorated with doves or falcons, only one other one with indefinable birds was found. Marinatos also pointed out that the Nestor cup from Mycenae was not suitable for drinking because its edge was cut off too sharp-edged, and assumed that the cup originally served cultic purposes and was later made into the shape of a drinking cup, which some elements suggest . Hilda L. Lorimer also represented that it was a libation vessel .

The "Nestor Cup" from Ischia

Archaeologist Giorgio Buchner found a drinking vessel during excavations in the necropolis of Pithekoussai near Monte Vico on the Italian island of Ischia in 1954. It was made in the last third of the 8th century BC. It was made in Rhodes and probably came through trade to Ischia, where it was used together with other clay dishes as a burial object for a 12 to 14 year old boy. This burial within the necropolis, unique in its complexity and vessel combination, can be traced back to the period between 725 and 720 BC due to the ceramics that were added. Classify.

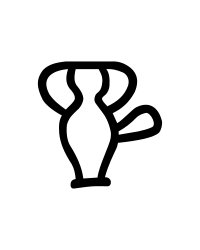

The vessel is 10.3 cm high and has a top diameter of 15.1 cm. Its basic shape corresponds roughly to that of a hemisphere, the capacity is a little more than a liter. The vessel stands on a finger-wide foot ring, which forms a base of 5.5 cm. The two horizontally attached handles are diametrically opposed to each other; they start a little below the edge at the point of the largest vessel circumference and rise almost to the level of the edge. The wall of the vessel is slightly drawn in above the handle and then runs vertically again, creating a narrow lip 0.5 cm high. The Greek name for this type of vessel is kotyle , which is often equated with skyphos .

The find is now in the Museo Archeologico di Pithecusae on Ischia.

The inscription

The vessel bears an inscription that was not scratched until after production. The three-line text was written from right to left and consists of a trimeter and two dactylic hexameters . Since some fragments are missing, only fragments of the text have been preserved. It reads:

ΝΕΣΤΟΡΟΣ: ...: ΕΥΠΟΤΟΝ: ΠΟΤΕΡΙΟΝ

ΗΟΣΔΑΤΟΔΕΠΙΕΣΙ: ΠΟΤΕΡΙ ..: ΑΥΤΙΚΑΚΕΝΟΝ

ΗΙΜΕΡΟΣΗΑΙΡΕΣΕΙ: ΚΑΛΛΙΣΤΕΦΑΝΟ: ΑΦΡΟΔΙΤΕΣ

This is translated and supplemented in the classic notation as follows:

Νέστορός (ἐγῶμι or ἐέν τι) εὔποτον ποτήριον ·

ὃς δ 'ἂν τοῦδε πίησι ποτηρίου, αὐτίκα κεῖεναρον

ἵμερος στεφἈνον μερος στκφἈάνδφος στκφἈάν Ἀμερος στκφἈς ομερος στηλσον υηρος αίτλσον ἵμερος στεφἈς ομερος.

Nestor's cup (I am, or: there used to be), from which you can drink well.

But whoever drinks from this cup will immediately seize the

desire (the gift) of the beautifully crowned Aphrodite .

What was in the gap in the first verse is highly controversial. Nearly a dozen suggestions were made; the two selected above (von Risch 1987 and Heubeck 1979) have in common that they complete the verse to a regular iambic trimeter , in contrast to the result of Schadewaldt's variant εἰμι ( eimi “I am”). The different approaches can be summarized in two groups, within which each proposal has roughly the same meaning. The variations of the first group assume that the cup speaks itself and even of itself ; this would correspond to a way of labeling vessels that was often found at the time. However, the demonstrative pronoun τοῦδε ( toûde “this”) would be difficult to explain because the cotyle in the second verse suddenly speaks of itself in the third person. A second version with στι ( esti “it is, there is”) or, metrically more plausible, ἐέν τι ( eén ti “it was, there was”) was therefore proposed . That would mean that Nestoris is only meant in the first verse, but "this" cup that the reader is just seeing in the second. This group also includes the reconstruction of the inscription in the picture above, which fills the gap in the first verse with ἔρροι ( érroi “fort with (Nestor's cup)”). The latest conjecture comes from Yves Gerhard, who suggests Νέστορος ἔ [ασον] εὔποτον ποτήριον : “ Do without Nestor's cup, as good as it is for drinking! But whoever drinks from this cup will immediately be seized by the desire of the beautifully crowned Aphrodite. "

Approaches to interpretation of the inscription

It is certain that Νέστορός ( Néstorós “des Nestor”) actually refers to the mythical king of Pylos and not the owner of the cup, since people were not named after heroes at the time the inscription was affixed .

In the versions of the first group, as indicated above, the content of the first and the two following lines differ, which is underlined by the change in meter . While the simple skyphos boldly declares himself to be the mythical cup of Nestor in the first verse, a symbol of the joy of drinking and persuasion, in the second and third verse he ascribes an effect that wine can trigger from very different vessels - love. The different versions of the second group, however, imply that the mythical Nestor cup (in the first) and the present Kotyle (in the second and third verse) are clearly distinguished. Here, too, the reader must therefore know the legendary mixing vessel of the King of Pylos, from whatever source. In the hexametric verses, the author turns away from Nestoris, which is apparently only intended to attract the reader's attention, and praises the simple pottery work, which appears to be more valuable than Nestor's magnificent mixing vessel due to this representation. In the last verse, both versions allude to the aphrodisiac properties of the wine; in this promise lies the advantage of the skyphus over the mythical Nestor cup.

Georg Danek refers to the manifold problems that arise from the assumption that the inscription refers to the Iliad: For example, the question arises as to how the phrase "... cup that is easy to drink from" applies to the heavy mixing vessel of the Iliad is to be played from which one has not drunk; In addition, the author of the inscription would have to have known the Iliad very well in order to be able to refer to the Nestor cup, which does not have an active role in the epic. Alternatively, Danek suggests using the second reconstruction variant (with "... there was ...") that the inscription alludes to the Kyprien . Menelaus visited Nestor there shortly after his wife Helena was kidnapped by Paris - this is only known from Proclus - and is asked by the old man to drink so that he can forget his grief:

οἶνόν τοι, Μενέλαε, θεοὶ ποίησαν ἄριστον

θνητοῖς ἀνθρώποισιν ἀποσκέδασαι μελεδῶνας.

O Menelaus, the gods made the best wine for

mortals to dispel sorrows.

While Menelaus is supposed to free himself from the pain of his love by drinking, the enjoyment of wine from the Pithekoussai clay cup has the opposite, common consequence of producing or intensifying the desire for love. The point of the poem lies in this contrast. Danek's interpretation has the advantage over those who see a reference to the Iliad that “... the passage from the Cyppri (...) actually cites a 'story', that is, a sequence of actions, which is also its decisive in the context of oral tradition The statement could be retained without therefore having to be fixed literally. ” Danek explains the demonstrative pronoun τοῦδε by saying that the verses were probably created at a symposium: The poet actually had this cup - the present Kotyle - in mind and was later recorded in writing .

Meaning of the "Nestor cup" by Pithekoussai

Regardless of the interpretation, the inscription on Nestor's cup of Ischia is of great historical importance: On the one hand, it is one of the earliest, relatively reliably datable Greek inscriptions in alphabetical form. Since the characters already differed significantly from the Phoenician , the alphabet must have been adopted some time beforehand. On the other hand, the inscription proves that the Greeks of the 8th century BC Knew the legends of and about the Nestor cup very well, from whatever context. Barry B. Powell, who claims that the inscription depends on the Iliad, assumes, like Schadewaldt, that the Homeric epics will spread very quickly and describes the three verses as "Europe's first literary allusion".

It is now communis opinio that there is an allusion . This is also justified by the fact that the verses contain numerous vertical dotted lines (cf. the reconstruction of the inscription in the figure above), which in the first verse only form word separators, but in the other two verses they are something different due to their insufficient number have to. These are obviously the hexametric caesuras and dihereses Kata ton triton trochaion and bucolic dihereses (v. 2) or penthemimers and the caesura named by Fränkel C – 1 (v. 3), which are markings for short reading breaks. If one also looks at the evenness of the letters and the parallel guidance of the two hexameter lines, it is obvious that the writing practice has been transferred from longer hexameter texts. Therefore, by the time the inscription was affixed, epic manuscripts have most likely already existed, however extensive. However, it will probably not be possible to conclusively clarify whether the epic in the background is actually the Iliad, the Cyprus or even older, unknown stories. The only thing that is certain is that the Nestor Cup from Ischia, contrary to the hopes that sprang up immediately after its discovery, does not provide a term ante quem for the dating of the Iliad.

swell

- Ludwig Bachmann : Scholia in Homeri Iliadem. Volume 1. Leipzig 1835, p. 499.

- Immanuel Bekker : Scholia in Homeri Iliadem. Volume 1. Berlin 1825, pp. 324-325.

- Wilhelm Dindorf : Scholia Graeca in Homeri Iliadem. Leipzig 1875, pp. 400-401.

- Hartmut Erbse : Scholia Graeca in Homeri Iliadem (scholia vetera). Volume 3. Berlin 1974, pp. 244-249.

- Georg Kaibel (Ed.): Athenaei Naucratitae Dipnosophistarum libri 15th Volumes 1 and 3. Leipzig 1887–1890, pp. 75–88.

- Wolfgang Schadewaldt: Homer. Iliad. Frankfurt am Main 2009, p. 189.

- Hermann Schrader (Ed.): Porphyrii quaestionum homericarum ad Iliadem pertinentium reliquias. Leipzig 1880, pp. 168-169.

- Marchinus van der Walk (Ed.): Eustathii archiepiscopi thessalonicensis commentarii ad Homeri Iliadem pertinentes. Volume 3. Leiden 1979, pp. 267-282.

- Martin L. West (Ed.): Homerus: Ilias. Rhapsodiae I-XII. Leipzig 1998, p. 340.

literature

General

- Arne Furumark: Nestor's Cup and the Mycenaen Dove Goblet . In: Gunnar Rudberg (Ed.): Eranos Rudbergianus . Vol. 44. Göteborg 1946, pp. 41-53.

- Reinhard Herbig (ed.): Legacy of ancient art. Guest lectures at the centenary of the Archaeological Collections of Heidelberg University . Heidelberg 1950, pp. 11-70.

- Alfred Heubeck : The Homeric Question. A report on research over the past few decades . Darmstadt 1974, pp. 222-228.

- Barbara Patzek: Homer and Mycenae. Oral poetry and historiography . Oldenbourg, Munich 1992, pp. 196-201.

- Wolfgang Schadewaldt: From Homer's world and work . Stuttgart 1965, pp. 413-416.

- Heinrich Schliemann: Mykenae. Report on my research and discoveries in Mycenae and Tiryns . Leipzig 1878, pp. 272-276 ( digitized version ).

To the Nestor cup of the Iliad

- Ludwig Braun: Hellenistic explanations of the "Nestor cup" . In: Mnemosyne . Vol. 26. Leiden 1973, pp. 47-54.

- Johann Baptist Friedreich : Realia in the Iliad and Odyssey . Erlangen 1856, pp. 254-257.

- Hilda L. Lorimer: Homer and the Monuments . London 1950, pp. 328-335.

- Erich Neu: Old Anatolia and the Mycenaean Pylos: Some thoughts on the Nestor cup of the Iliad . In: Archives Orientální . Vol. 67, 1999, pp. 619-627.

To Schliemann's mug

- Spyridon Marinatos: The "Nestor Cup" from the IV. Shaft grave of Mycenae . In: Reinhard Lullies (Ed.): New contributions to classical antiquity: Festschrift for the 60th birthday of Bernhard Schweitzer . Stuttgart and Cologne 1954, pp. 11-18.

- Thomas Bertram Lonsdale Webster : From Mycenae to Homer. Beginnings of Greek literature and art in the light of Linear B . Oldenbourg, Munich 1960.

To the Nestor cup from Pithekoussai

- Klaus Alpers : An observation about the Pithekussai Nestor cup . In: Glotta . Vol. 47, 1969, pp. 170-174.

- Georg Danek: The Nestor Cup from Ischia, epic quotation technique and the symposium . In: Wiener Studien , Vol. 107, Vienna 1994, pp. 29–44.

- Klaus Rüter / Kjeld Matthiessen: To the Nestor cup from Pithekussai . In: Journal of Papyrology and Epigraphy . Vol. 2. Bonn 1968, pp. 231-255.

- Ernst Risch : To the Nestor cup from Ischia . In: Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik , Vol. 70, 1987, pp. 1-9.

- Yves Gerhard: La "coupe de Nestor": reconstitution du vers 1. In: Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik , Vol. 176, 2011, pp. 7-9.

Web links

- Metric translation of the Iliad by Johann Heinrich Voss

- Picture and description of a copy of the gold cup found by Schliemann at the Hermann von Helmholtz Center for Cultural Technology at HU Berlin

- High-resolution reconstruction of the inscription on the "Nestor Cup" from Ischia (English)

- Website of the Archaeological Museum of Pithekoussai

Individual evidence

- ↑ See Alciato's epigram “Scyphus Nestoris”. Andrea Alciato: Les emblemes. Lyon 1549/1550, pp. 110-111.

- ↑ See Schiller's ballad “ Das Siegesfest ”. Anton Doll (Ed.): Friedrich Schiller's complete works. Vol. 10. Vienna 1810, pp. 199–204, especially V. 121–128.

- ↑ Braun, p. 48.

- ↑ Athenaios, 11, 488b – d, Vol. 3, pp. 75–76.

- ↑ Eustathios, 869, 54-55, p. 278.

- ↑ Dindorf, p. 401.

- ↑ Eustathios, 869, 27, p. 276.

- ↑ Athenaios, 11, 488d – e, Vol. 3, p. 76.

- ^ West, p. 340.

- ↑ Furumark, p. 47.

- ↑ Athenaios, 11, 488f-489a, Vol. 3, pp. 76-77.

- ↑ a b Bachmann, p. 499.

- ↑ Eustathios, 869, 6, p. 275.

- ↑ Eustathios, 869, 7-8, p. 275.

- ↑ Eustathios, 870.34, p. 281.

- ↑ a b Bekker, p. 325.

- ↑ Eustathios, 870, 46-47, p. 281.

- ↑ Porphyrios, pp. 168-169.

- ↑ Furumark, pp. 52-53; Rüter / Matthiessen, pp. 251–252; Patzek p. 199.

- ↑ Athenaios, 11, 493b – c, Vol. 3, p. 86.

- ↑ Dindorf, p. 401; Pea, p. 247.

- ↑ Athenaios, 11, 493a, Vol. 3, p. 86; Eustathios, 870, 35-39, p. 281.

- ↑ Pea, pp. 247-248.

- ↑ Athenaios, 11, 493b, Vol. 3, p. 86.

- ↑ a b Porphyrios, p. 168.

- ↑ Athenaios, 11, 493c – e, Vol. 3, pp. 86–87.

- ↑ Athenaios, 11, 489c-492f, Vol. 3, pp. 78-86.

- ↑ Furumark, pp. 52-53; Patzek, 196-202.

- ↑ Athenaios, 11, 489c-d, Vol. 3, p.78.

- ↑ New, pp. 619–627.

- ↑ Marinatos, p. 14.

- ↑ Herbig, p. 22; Lorimer, p. 328; Marinatos, pp. 17-18.

- ↑ Schliemann, pp. 272-276; Furumark, pp. 41-53.

- ↑ Patzek, p. 197.

- ↑ Marinatos, p. 15f.

- ↑ Lorimer, p. 333.

- ↑ Marinatos, p. 16.

- ↑ Marinatos, pp. 17-18.

- ↑ Lorimer, pp. 331-333.

- ^ Rüter / Matthiessen, p. 235.

- ↑ Rüter / Matthiessen, pp. 232-234.

- ↑ after: Rüter / Matthiessen, p. 241.

- ↑ Rüter / Matthiessen, p. 245.

- ^ Yves Gerhard: La "coupe de Nestor": reconstitution du vers 1. In: Journal for papyrology and epigraphy . 176, 2011, pp. 7-9.

- ^ Rüter / Matthiessen, p. 246.

- ^ Rüter / Matthiessen, pp. 231–255.

- ↑ Available online in English at

- ↑ Athenaios, 1.35c, Vol. 1, p. 81.

- ↑ Danek, p. 35.

- ↑ Danek, pp. 29-41.

- ^ Barry B. Powell: Who Invented the Alphabet: The Semites or the Greeks? ( Memento of December 30, 2005 in the Internet Archive ), 1998.

- ↑ Eric A. Havelock in particular expressed himself differently, who, unlike Danek, considered the possibility of a purely orally transmitted legend motif; see. Joachim Latacz : The function of the symposium for the emerging Greek literature . In: Wolfgang Kullmann / Michael Reichel (ed.): The transition from orality to literature among the Greeks . Narr, Tübingen 1990, pp. 232-233.

- ↑ Alpers, p. 172.

- ↑ See Schadewaldt, p. 415.