Notiomastodon

| Notiomastodon | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Skeletal reconstruction of Notiomastodon |

||||||||||||

| Temporal occurrence | ||||||||||||

| Middle to Upper Pleistocene | ||||||||||||

| 460,000 to 11,000 years | ||||||||||||

| Locations | ||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Notiomastodon | ||||||||||||

| Cabrera , 1929 | ||||||||||||

Notiomastodon is an extinct genus of the Gomphotheriidae familywithin the order of the proboscis . It livedin South America from the Middle to the Upper Pleistocene around 460,000 to 11,000 years ago. There the animals mainly used the lowland areas east of the Andes . The representatives of Notiomastodon reached about the size of today's Asian elephant . Like other South American gomphotheries such as Cuvieronius from the highlands of the Andes and some North American forms, such as Stegomastodon , Notiomastodon was characterized by a short-snouted and highly domed skull. The short snout was created by the regression of the lower tusks , which weremostly preservedin the gomphotheries of Eurasia and Africa . In Notiomastodon, special features can be foundin the shape of the upper tusks, which oftenlackeda covering of tooth enamel , and also in the design of the molars. The clearly bumpy chewing surface pattern distinguishes the animals as consumers of mixed vegetable food, which could be composed differently locally. In the course of the last glacial period there was an adaptation to grass food. The genus was scientifically introduced in 1929. It has been controversial in the course of research history or has beenconfused or equatedwith a form called haplomastodon and stegomastodon . Intensive anatomical studies since the 2010s have shown that Notiomastodon represents the only proboscis form in the lowlands of South America, that Haplomastodon is identical to it and that Stegomastodon is restricted to North America.

features

size

Notiomastodon was a medium-sized to large proboscis. Based on a complete skeleton, a shoulder height of around 2.5 m and a body weight of around 3.15 t could be reconstructed, other data amount to up to 4.4 t for the same individual. For another individual, the weight calculations vary between 4.1 and 7.6 t. Since the assumptions are based on the dimensions of the limb bones, but these differ proportionally from recent elephants, the values can only be regarded as an approximation. The animals were generally roughly the size of today's Asian elephants ( Elephas maximus ).

Skull and dentition features

Notiomastodon's skull was short and tall, compared to its relative Cuvieronius it looked narrower and shorter. When viewed from the side, it arched like a dome, comparable to the skulls of today's elephants. However, the skull of the recent elephants is more prominently oriented vertically and the rostrum is shortened even further. Individual skulls found had total lengths of 75 to 113 cm, the height of these, measured from the upper edge to the level of the alveoli, was 41 to 76 cm. The upper edge of the skull was shaped from the front by two lateral humps, between which there was a slight indentation along the middle of the skull. Both humps were created by the air-filled chambers in the bones of the brain skull, which are typical of the trunk. They were clearer than in comparison to Gomphotherium . The forehead was broad and largely flat. The nose was short, as in all developed proboscis animals and lay on top of the very wide but shallow nostril where the trunk ansetzte. A furrow laterally bounded the nasal bone, which served as an anchor point for the maxillo labialis muscle . The muscle acted as a lifting arm for the trunk. The remaining edges of the nostril were formed by the median jawbone and individual processes from it. The middle jaw bone also formed the alveoli of the upper tusks. These were very long, sometimes up to 59 cm, and overall very wide. Their diameter increased towards the front. They diverged only slightly from each other, in side view they formed a line with the forehead. This created a wide angle between the orientation of the tusk alveoli and the plane of the chewing surface of the molars. The tusk alveoli were slightly indented on the upper side. Overall, the median jaw bone was significantly more massive than that of Gomphotherium . Due to the shortening of the skull in the snout area, the orbit of Notiomastodon was above the front end of the posterior row of teeth, which is noticeably further forward than in the long-snouted gomphotheria such as Gomphotherium or Rhynchotherium . The zygomatic arch was massive and high. The upper edge was rather straight, the lower edge showed a slight indentation where the masseter muscle began.

The lower jaw was up to 77 cm long, in the area of the teeth the body of the lower jaw was significantly widened and here also noticeably bulged at the lower edge. Its height below the molars was up to 15 cm. In contrast to this, Stegomastodon had a largely straight lower edge. The symphysis was typically relatively short for South American gomphotheres ( brevirostrin ), in some individuals they went striking downward, forming sometimes a small extension, as well as at cuvieronius is the case. The downward symphysis is considered to be a rather original feature. In contrast , the process of stegomastodon was significantly reduced. Sometimes there were up to three foramina merntals . The ascending joint branch was massive and rose up to 47 cm. The leading and trailing edges showed a parallel orientation. The crown process was significantly lower than the articular process, which was not the case with stegomastodon . The joint ends were perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the lower jaw and were strongly developed, the outer edges were up to 57 cm apart. Also in contrast to stegomastodon , the angular process was less prominent.

The set of teeth was made up of the tusks and the molars. In contrast to the more primitive Eurasian gomphotheries, tusks were only formed in the upper dentition, although small alveoli sometimes formed on the lower jaw . As in all proboscis, the upper tusks represented the hypertrophied second incisors . There were individual variations in terms of the shape of the tusks, so that the tusks were either short and with the tips clearly curved upwards or rather straight. A sheath made of tooth enamel was mostly not developed in adult individuals. This differs from Cuvieronius , whose upper tusks were spiraled around by enamel bands. In addition, the latter also had lower tusks in young animals. In general, the tusks of Notiomastodon were very robust. Its length was up to 88 cm outside the alveoli, in particularly long specimens it reached up to 128 cm measured over the outer curvature. The cross-section was oval and varied from 11.5 to 16.4 cm. In Notiomastodon, like in today's elephants, the rest of the dentition was composed of the premolars and molars , which broke through one after the other due to the horizontal change of teeth . The chewing surface was generally composed of several pairs of cusps, which gave the teeth a bunodontic pattern. The first two molars had three pairs of cusps ( trilophodont ) oriented transversely to the longitudinal axis of the tooth . The upper third, however, had four and the lower up to five pairs of cusps ( tetra- and pentalophodont ), with these additional cusps being less developed. In Stegomastodon, on the other hand, there were five ridges above and up to eight below. In addition, two morphotypes can be identified in Notiomastodon in relation to the molars, one with additional central cusps on each longitudinal half of a tooth and one without them. The cloverleaf-shaped structure of the individual humps was also characteristic when chewed off. Overall, the tooth structure of Notiomastodon was characterized by a rather original character, which more closely resembled that of Cuvieronius . But because of the different morphotypes he approached the complex Kauflächenmuster of stegomastodon was wass mainly caused by the formation of additional Nebenhöckerchen. The last molar in Notiomastodon could have between 35 and 82 cusps, in Cuvieronius it was 33 to 60 and in Stegomastodon 57 to 104. Accordingly, the total occlusal surface of the last molar in Notiomastodon was 57 to 160 cm² (12 to 32 cm² per groin) and at Stegomastodon 72 to 205 cm² (12 to 34 cm² per bar). As a result, the teeth were relatively large, typical of developed proboscis. The lower last molar measured up to 21.6 cm in length, the upper last up to 19.3 cm.

Skeletal features

In the postcranial skeleton structure, Notiomastodon was largely similar to today's elephants, but was generally more robust. The humerus was massive and 78 to 87 cm long. It discharged far at the joint ends, the joint head was wide and clearly rounded. However, individual roughened surfaces on the shaft showed only a few prominent elevations. The ulna was rather delicate, with a total length of 75 to 80 cm but almost as large as the humerus. Due to the massive olecranon , the upper articular process, the physiological length of the bone was only 57 to 64 cm. As a result, the cubit was functionally significantly shorter than or humerus, which is characteristic of the South American gomphotheria compared to their Eurasian relatives. The physiological length of the ulna also roughly corresponded to the total length of the radius . The thigh bone was 96 to 100 cm long and consisted of an almost cylindrical shaft, only slightly flattened at the front and back. The spherical head rose significantly above the Great Rolling Hill, but sat on a shorter neck compared to Cuvieronius . At the lower joint, the inner joint role was larger than the outer. The up to 70 cm long shin was characterized by a prismatic shaft and an upper joint end that was wider than the lower end. As with today's elephants, the forefoot and hind foot each had five rays. The limbs of Notiomastodon were, like other short-snouted gomphotheries, generally more massive and robust than those of today's elephants. Also striking was the more balanced length between the upper and lower leg sections of Notiomastodon compared to both the recent elephants and Stegomastodon . In the latter, the femur was almost twice as long as the shin. Another important difference is found in the ratio of the length of the front legs to the rear legs. In Notiomastodon this is an average of 82%, in Stegomastodon 93%, which means that the hind legs of the former were significantly shorter than the front legs. Both the relation of the upper and lower leg sections as well as that of the front and rear legs to each other give Stegomastodon a significantly better adaptation to open landscapes and long walks ( graviportal ) than is the case with Notiomastodon . This is also reflected in the construction of the feet, which in Notiomastodon were slimmer and higher than in Stegomastodon .

distribution

The distribution area of Notiomastodon extended almost over all of northern, eastern and southern South America. The representatives of the proboscis were found mainly in the lowlands, in the highlands of the Andes it was replaced by Cuvieronius . It is possible that the two representatives of the proboscis avoided direct competition through their strict habitat delimitation , as they each had a similar ecological spectrum. As habitats can be for notiomastodon especially savannas and dry grasslands reconstruct that existed under warm to temperate climates. As a result, the limit of distribution was found around the 37th to 38th parallel south. Important fossil records are available from the pampas region and the Gran Chaco of Argentina . These include Santa Clara del Mar in the province of Buenos Aires and the Río Dulce in the province of Santiago del Estero . There is also evidence of remains from southern Bolivia , which still belongs to the Gran Chaco landscape. Otherwise, finds from Cuvieronius were mainly reported from the state . The southern records of the proboscis genus also include individual remains from central Chile .

Other finds are known from Brazil , where Notiomastodon occurred widespread from the southern open land areas of the Chaco to today's Amazon basin , and fossil remains have been recovered from the continental shelf off the Atlantic coast. One of the most important sites, however, is Águas de Araxá in the Brazilian state of Minas Gerais . At least 47 individuals of Notiomastodon were discovered here. This superimposed with a coarse-grained sediments filled Kolk . The genus has also been reported from Peru , Ecuador , Colombia and Venezuela . In Ecuador, the Quebrada Pistud site near Bolívar in the Carchi province is worth mentioning. This contained around 160 fossil remains of Notiomastodon in flood-like deposits spread over several dozen square meters. They represent at least seven individuals, a single skeleton consisting of 68 bone elements spread over around 5 m². Another important find here is the natural asphalt mine of Tanque Loma on the Santa Elena peninsula , which contained over 1000 individual bones. A good 660 of these were examined in more detail, about 11% can be made about notiomastodon . They are distributed among three individuals, including two young animals.

Paleobiology

Diet

The bunodonte chewing surface pattern of the gomphotheria is mostly associated with a less specialized diet, which suggests a preference for mixed vegetable foods. This is also underlined by studies of signs of wear on the molars of Notiomastodon from the Upper Pleistocene site of Águas de Araxá in the Brazilian state of Minas Gerais . The teeth have a high number of scratches and nicks, which is consistent with similar abrasion marks on the teeth of today's ungulates on a diet of both soft and hard vegetable foods. Conifers , knotweed and potted ferns could be identified as the basis of food through some plant remains from the teeth . In contrast, isotope analyzes of numerous fossils from large areas of South America paint a more complex picture. For animals of the Upper Pleistocene from the northern and central parts of South America such as Ecuador or the Gran Chaco, these resulted in a predominance of C 4 plants in the food spectrum , while those from the more southern sections such as the Pampa region mainly nourished on C 3 plants . In the areas in between, a mixed vegetable diet can be reconstructed using the isotope ratios. However, this also applies to individuals from the Middle Pleistocene of southern South America. This was particularly evident in the fossil finds at a site, Quequen Grande in the Argentine province of Buenos Aires . Here, isotope studies on finds from the Middle Pleistocene indicate a rather mixed vegetable diet, while others from the Upper Pleistocene indicate a specialized grass diet. May have been notiomastodon by an opportunistic herbivores, who adapted to local conditions its food habits, like it has for today's elephants. This was an important adjustment phenomenon, especially in the course of the Upper Pleistocene, when due to the climatic changes of the last glacial period in the southern part of South America the tree population dwindled and was replaced by grasslands.

Population structure and reproduction

The Águas de Araxá site is significant because it contained one of the largest collections of Notiomastodon fossils. They are interpreted as the remains of a local population that was wiped out by a catastrophic event. After examining the teeth, the group consisted of 14.9% young animals (0 to 12 years of age), 23.0% of nearly full-grown individuals (13 to 24 years of age) and 62.1% of adult animals (25 years of age and older ). The latter can be further subdivided into 27.7% middle-aged (25 to 36 years) and 17.2% old (37 to 48 years) and extremely old (49 to 60 years) animals. What is remarkable about this is the large proportion of individuals with an age of 37 years and over, which suggests a high survival rate within this group. Some of the adult animals suffered from pathological bone changes such as Schmorl's cartilage nodules , osteomyelitis and osteoarthritis . These showed up on the vertebrae and long bones, among other things, and may be due to individual diseases. At least osteomyelitis was also diagnosed in finds of Notiomastodon from other sites. The remains of Águas de Araxá must have been lying open for a long time after they were deposited. Not only do bacon beetles drill holes in the bones, but also bite marks from larger representatives of dogs such as Protocyon . The gnaw marks are probably the result of scavenging, possibly as a result of a period of food shortage. Because of its size, Notiomastodon was unlikely to have natural enemies. Traces of a larger predator were also found on a skeleton from the Pilauco site in southern Chile .

The last four years of life of a tusk of a male animal from the basin of Santiago de Chile were analyzed using isotope analyzes and thin sections . During this time, the tusk increased in thickness by around 10 mm per year. The growth rate turned out to be cyclical and was interrupted in the early summer of the year by reduced dentin growth . The period of reduced growth is interpreted with the entry into the musth , a hormone-controlled phase that occurs annually in today's elephants and is characterized by a massive increase in testosterone . During the musth, bulls are extremely aggressive and fight dominance fights for the mating privilege, sometimes with fatal results. An external characteristic is the increased flow of secretion from the temporal gland. In the animal from Santiago de Chile, the growth anomalies were partly associated with a changed diet. The death of the individual occurred relatively abruptly in early autumn.

Locomotion

So far, trace fossils of proboscis are relatively rare in South America. One of the most important sites is found with Pehuén-Có near Bahía Blanca in the Argentine province of Buenos Aires. The site was discovered in 1986 and extends over an area of 1.5 km². The innumerable traces are imprinted in an originally soft substrate. A wide variety of mammals can be detected, such as the camel-like Megalamaichnum ( Hemiauchenia ), the South American ungulate Eumacrauchenichnus ( Macrauchenia ), the great armadillo- related Glyptodontichnus ( Glyptodon ) or the giant ground sloth Neomegatherichnum ( Megatherium ), from the group are also birds from Aramayoichnus ( Megatherium ) the rhea demonstrated. Due to the diversity of the traces, Pehuén-Có is one of the world's most important sites with Ichnofossils. The age is dated to 12,000 years ago. Proboscid traces are rare here too. The main lane includes seven step seals over a length of 4.4 m. The individual prints have an oval shape with lengths of 23 to 27 cm and widths of 23 to 30 cm. As a rule, they are sunk about 8 cm into the ground. Sometimes there are smaller bulges on the front edge, which are interpreted as indications of three to five toes, comparable to the “nail-like” structures of today's elephants. The forefoot prints that are regarded as larger therefore have five such bulges, while those of the smaller ones in individual cases only have three such bulges. The flat shape of the step seal also refers to the cushioned soles of today's elephants. The footprints of Pehuén-Có be the track genus Proboscipeda assigned as its synonym acts Stegomastodonichnum .The size of the footprints suggesting a Rüsseltier the size of the Asian elephant close, which roughly with notiomastodon matches.

Systematics

|

Internal systematics of the Gomphotheriidae according to Cozzuol et al. 2012

|

Notiomastodon is a genus from the extinct family of Gomphotheriidae within the order of Rüsseltiere (Proboscidea). As a relatively successful and long-lived order group, the proboscis can already be identified in the late Paleocene . Their origins lie in Africa , they achieved a great diversity and wide distribution in the course of their tribal history both in the ancient and in the new world . Several radiation phases can be distinguished. The gomphotheries belong to the second phase, which began in the Lower Miocene . A general characteristic of all (real) gomphotheries is the formation of three transverse ridges on the first and second molar ( trilophodontic gomphotheria; more modern forms with four ridges are sometimes referred to as tetralophodontic gomphotheries, but are no longer part of this family). Like today's elephants , the gomphotheria had a horizontal change of teeth and thus belong to the more modern group of elephantimorpha compared to their ancestors . With the horizontal tooth change, in contrast to the vertical tooth change common for most mammals, in which all teeth of the permanent dentition are available at the same time, the individual molars are pushed out one after the other. It was created by the shortening of the lower jaw in the course of the evolution of the proboscis and was first detectable in Eritrea at the end of the Oligocene around 28 million people. In contrast to today's elephants, the gomphotheria still had some primitive and different characteristics. These include, for example, a generally flatter skull, the formation of tusks in both the upper and lower rows of teeth and molars with a smaller number of ridges and a tubercular pattern of the chewing surface. For this reason, the Gomphotheria are often placed in their own superfamily, the Gomphotherioidea , which stands opposite the Elephantoidea with their current representatives. Sometimes they are also considered members of the Elephantoidea. Overall, the gomphotheria form one of the most successful groups of proboscis, which have undergone numerous changes over the long period of their existence. These include a substantial general increase in size, especially of the tusks and molars, as well as an increasing complexity of the molars.

|

possible relationship of the short-snouted gomphotheria according to Mothé et al. 2019

|

The gomphotheria are documented for the first time at the end of the Oligocene in Africa and are among the first representatives to leave the continent after the closure of the Tethys and the creation of the land bridge to Eurasia in the transition to the Miocene. Achieved thereby, among other Gomphotherium during the Miocene epoch, about 16 million years ago on the Bering Strait Coming also North America , in Central America , they are the first time in the late Miocene epoch, about 7 million years detectable. South America entered the gomphotheria in the course of the Great American Fauna Exchange around 3.5 to 2.5 million years ago. The South American gomphotheria differ from their relatives in Eurasia and North America by their comparatively short rostrum ( brevirostrine gomphotheria) and higher domed skull. In addition, tusks were only formed in the upper dentition. The two genera known from South America ( Notiomastodon and Cuvieronius ) together with their North American relatives ( Stegomastodon ) form a monophyletic group that represents the subfamily of the Cuvieroniinae ; in some cases, the forms mentioned are also embedded together with Rhynchotherium in a larger group called Rhynchotheriinae . Some researchers share the opinion that Cuvieronius is a direct successor to Rhynchotherium , which is expressed in the highly specialized upper tusks, which are wrapped in a spiral of enamel. Notiomastodon would then in turn descend directly from Cuvieronius . This view was supported by the knowledge that young animals of Cuvieronius, in contrast to adult individuals, still have lower tusks, while with Rhynchotherium the lower tusks occur in all life stages. Disregarding this recent development, the relationships within the short-snouted gomphotheries are largely unexplained. The main problem here is Sinomastodon , a form from East Asia with skeletal features similar to those of the South American gomphotheria. In several phylogenetic studies, Sinomastodon forms a unit with Stegomastodon , Cuvieronius and Notiomastodon , whereby its presence in East Asia is interpreted by migrating back from the American areas of distribution. Due to its geographical isolation from the American genera, Chinese scientists place the form in its own subfamily, the Sinomastodontinae . Because of the lack of intermediate forms, some authors see the similarities between Sinomastodon and the South American gomphotheries only as a convergent formation.

|

Internal systematics of the proboscis according to Buckley et al. 2019 based on biochemical data

|

The assumed relationships among the extinct proboscis are based on skeletal anatomical features, as is the case with many groups of mammals that have only survived in fossil form. It is only since the 2000s that molecular genetic and biochemical analysis methods have also played an increasingly important role. In the case of the elephants, besides the woolly mammoth ( Mammuthus primigenius ), the prairie mammoth ( Mammuthus columbi ) and the European forest elephant ( Palaeoloxodon antiquus ) from the elephant family, the American mastodon ( Mammut americanum ) from the Mammutidae family has also been sequenced so far. Notiomastodon is currently the only representative of the gomphotheria for which biochemical data are available for comparison. In contrast to the anatomically assumed closer relationship to the elephants, however, according to a study from 2019, there was a closer relationship to the mammoths. It is currently unclear whether the result can be transferred to the entire group of gomphotheria.

One species is recognized within the genus:

- N. platensis ( Ameghino , 1888)

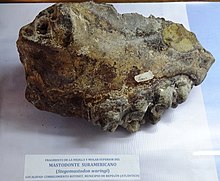

In the course of the history of research, several other forms have been described, some of which are associated with Notiomastodon ( N. ornatus ), and some with Haplomastodon ( H. waringi , H. chimborazi ), but are now considered synonymous with N. platensis .

Tribal history

Origins

The appearance of the gomphotheria in South America is connected with the Great American Faun Exchange . This began in the Pliocene around 3.5 million years ago when the Isthmus of Panama closed, creating a permanent land connection between North and South America. The fauna exchange worked in both directions, so that, for example, giant sloths and glyptodons or South American ungulates reached the north, while predators and cloven-hoofed animals , but also proboscis, mixed with the fauna of South America, which had been endemic up until then . The oldest record of proboscis from South America is from the central section of the Uquía Formation in northwestern Argentina . It dates to an age of around 2.5 million years. The finds there, fragmented vertebral remains, cannot currently be assigned to a specific genus. When is the emergence of differentiation notiomastodon came is unknown. In Central America there are no clear records of the genus. It was here that Cuvieronius first appeared around 7 million years ago. It is often assumed that the gomphotheries opened up South America in two independent settlement waves. Cuvieronius used a western corridor over the Andes , while Notiomastodon used an eastern one along the Atlantic coast and the lowlands. However, it is possible that the settlement of South America was much more complex, as Cuvieronius in Central America does not show any strict ties to high altitudes, but can also be detected here in lowlands. The earliest evidence of Notiomastodon in South America are currently individual teeth from the continental shelf off the coast of the Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul , which were radiometrically dated to around 464,000 years and thus belong to the Middle Pleistocene . The vast majority of the finds from Notiomastodon belong to the late Middle and Upper Pleistocene. Notiomastodon possibly reached the central Chilean distribution areas relatively late, either via a route from the pampas region in the east over low-lying valley sections of the Andes or from the lowlands of the Amazon further north. This may have happened during the warmer periods of the last glacial period , when the Patagonian ice sheet was less extensive.

die out

In the late phase of the phylogenetic development, Notiomastodon appeared together with the first human hunter-gatherer groups in South America. Similar to other large mammals, the proboscis form then disappeared in the course of the Quaternary extinction wave , the exact causes of which are the subject of an unfinished, sometimes controversial, scientific discourse. It is still unclear whether the Paleo-Indians played a significant role in the extinction of Notiomastodon through active hunting . In total, there are far fewer than a dozen sites in South America where Notiomastodon is found associated with human remains. These are distributed across northern and southwestern South America; in the entire pamphlet region, not a single site is currently known with a common occurrence of proboscis and humans. There is therefore very little actual evidence of active hunting. Among the most important are the finds from Taima taima in the coastal zone of north-central Venezuela. A projectile point of the El Jobo type was found in a skeleton of Notiomastodon , and the site also contained the remains of the large ground sloth Glossotherium . The age of the finds dates to around 13,000 years ago. The finds from Monte Verde in central Chile, some 11,900 years ago, are sometimes associated with human hunting. The pieces here are partly highly fragmented and are often limited to teeth and tusk parts as well as individual skeletal elements, so that some authors assume that the remains of the proboscis originated from carcasses located elsewhere and were entered. The most recent data for Notiomastodon have age values of 11,740 to 11,100 years ago and were obtained from Quereo in central Chile, from Itaituba on the Rio Tapajós in central Brazil and from Tibitó in Colombia; the remains of the proboscidos are associated with around three dozen stone implements. A skull from Taguatagua could be even younger in Chile, the age of which is put at 10,300 years earlier than today. On the other hand, various scientists are calling for a review for individual sites with find data in the Lower Holocene such as Quebrada Ñuagapua in Bolivia.

Research history

Early proboscid research in South America

Traditionally, several representatives of the late Pleistocene gomphotheria were distinguished in South America. These include on the one hand the highland form Cuvieronius from the Andes , whose position is undoubted, on the other hand they also include various flatland representatives such as Haplomastodon and Notiomastodon . In addition, there is stegomastodon , which actually had a North American distribution. The relationships between the three last-named genres and their respective independence or synonymy are still controversial today. Research into the South American proboscis began with Alexander von Humboldt's expeditions in the transition from the 18th to the 19th century. From his collection of finds, Georges Cuvier published two teeth in 1806, one of which came from the area around the Imbabura volcano near Quito in Ecuador , the other from Concepción in Chile . Cuvier did not specify any species names that are valid today, but referred the former tooth to "Mastodonte des cordilléres" and the latter to "Mastodonte humboldien". Gotthelf Fischer von Waldheim then coined the first scientific species names of South American proboscis in 1814 by renaming Cuviers "Mastodonte des cordilléres" to Mastotherium hyodon and "Mastodonte humboldien" to Mastotherium humboldtii . Cuvier himself referred both species to the now no longer recognized genus " Mastodon " in 1824 , but created a new species name for the Ecuadorian finds with " Mastodon " andium (he placed the Chilean finds under " Mastodon " humboldtii ). From today's perspective, both teeth do not have any specific diagnostic features that can be assigned to a certain type. In the following period, the fossil record increased gradually, which prompted Florentino Ameghino in 1889 to give an initial overview of the proboscis in an extensive work on the extinct mammals of Argentina. Here he listed several species, all of which he classified as " Mastodon " analogous to Cuvier . In addition to the species already created by Cuvier and Fischer, Ameghino also mentioned some new ones, including " Mastodon " platensis , which he had established a year earlier and whose description was based on a tusk fragment from San Nicolás de los Arroyos in the Argentine province of Buenos Aires (copy number MLP 8-63). Henry Fairfield Osborn used " Mastodon " humboldtii in 1923 to scientifically introduce the genus Cuvieronius (his genus name Cordillerion , coined in 1926 with reference to " Mastodon " andium, is now considered identical to Cuvieronius ). Forty years after Ameghino, Ángel Cabrera revised the South American proboscis finds. He named the genus Notiomastodon and assigned it to the new species Notiomastodon ornatus , which he founded on a lower jaw and again on a tusk fragment from Playa del Barco near Monte Hermosa, also in the province of Buenos Aires (copy number MACN 2157). Ameghinos " Mastodon " platensis, however, he assigned stegomastodon and equated the species with some of Ameghinos older names. The genus Stegomastodon goes back to Hans Pohlig from 1912, who referred it to lower jaw finds from North America.

In the further north of South America, Juan Felix Proaño discovered an almost complete skeleton near Quebrada Chalán near Punin in the Ecuadorian province of Chimborazo in 1894 . The skeleton prompted him in 1922 to set up the form “ Masthodon ” chimborazi . In 1929, however, it was almost lost in a fire at the University of Quito together with a skeleton that had been recovered the year before at Quebrada Callihuaico near Quito. Some of the skeleton from Quebrada Chalán after the fire still preserved bones like the left and right humerus then took Robert Hoffstetter in 1950 to haplomastodon introduce, which he as a subgenus of stegomastodon auswies. He adopted Haplomastodon chimborazi as the type species (specimen numbers MICN - UCE -1981 and 1982; in 1995 Giovanni Ficcarelli and fellow researchers identified a neotype with specimen numbers MECN 82 to 84 from Quebrada Pistud in the Ecuadorian province of Carchi , which also had a complete skeleton includes). Only two years later, Hoffstetter raised Haplomastodon to the genus level, and as the main criterion for differentiating the two genera he cited the lack of transverse openings on the atlas (first cervical vertebra) in Haplomastodon . Within the genus he distinguished two sub-genera at the same time, Haplomastodon and Aleamastodon , which also differed from each other on the axis in the absence and occurrence of such bone openings .

Stegomastodon , Notiomastodon and Haplomastodon

Since the establishment of Stegomastodon by Pohlig in 1912, Notiomastodon by Cabrera in 1929 and Haplomastodon as an independent genus by Hoffstetter in 1952, there has been a lot of discussion about the validity of the three forms. As recently as 1952, Hoffstetter had restricted Haplomastodon to northwestern South America; for the remaining finds, for example from Brazil , he preferred a position within Stegomastodon . This was rearranged by George Gaylord Simpson and Carlos de Paula Couto in their extensive Mastodonts of Brazil in 1957 . Here the two authors referred all Brazilian fossil finds to Haplomastodon . The other two genera Notiomastodon and Stegomastodon, however, saw them spread further south in the Pampa region. The features of the transverse foramina on the first cervical vertebra, which Hoffstetter used to distinguish haplomastodon from stegomastodon, proved to be very variable, even within a single individual, according to the investigations of Simpson and Paula Couto. Both therefore emphasized the more upwardly curved upper tusks, which are not covered with enamel , as a diagnostic feature of haplomastodon compared to notiomastodon and stegomastodon . Simpson and Paula Couto designated the type species as Haplomastodon waringi . The species name goes back to " Mastodon " waringi , a taxon that William Jacob Holland introduced in 1920. The basis for this was a strongly fragmented lower jaw from Pedra Vermelha in the Brazilian state of Bahia , due to the earlier naming, in the opinion of Simpson and Paula Couto and in accordance with the nomenclature rule of the ICZN, it had priority over Haplomastodon chimborazi . The plausibility of the species name was often criticized, including by Hoffstetter himself, since the type material from Brazil is not very meaningful due to its state of preservation. Other authors followed this view and considered Haplomastodon chimborazi to be the valid nominate form (however, in 2009 the taxon “ Mastodon ” waringi was conserved by the ICZN due to its frequent mention in the scientific literature).

In 1995, María Teresa Alberdi and José Luis Prado synonymized Notiomastodon with Stegomastodon and put the species Stegomastodon platensis out. At the same time, they also equated Haplomastodon with Stegomastodon and named the species with Stegomastodon waringi . According to this view, there was only one genus of Gomphotheria in the South American lowland regions at that time, with Stegomastodon . In 2008, however, Marco P. Ferretti spoke out in favor of an independent position for Haplomastodon , but at the same time doubted the independence of Notiomastodon compared to Stegomastodon . Only two years later he presented an extensive work on the skeletal anatomy of Haplomastodon , in which he clearly differentiated the shape from Stegomastodon and gave it an intermediate position between this and Cuvieronius in the South American Andes. Around the same time, Spencer George Lucas and fellow researchers came to a similar conclusion, especially after examining a nearly complete skeleton of stegomastodon from the Mexican state of Jalisco and discovering that the genus should be separated from the South American gomphotheries due to a different musculoskeletal system. From Notiomastodon they discontinued Haplomastodon through a more complex chewing surface of the molars in the former. According to this, at least two generic representatives of the gomphotheria lived in the lowlands of South America. The analyzes of a research team led by Dimila E. Mothé in the early 2010s then produced a different result . After examining numerous proboscis material from South America, it found that, besides Cuvieronius from the Andean region, only one other genus occurred in South America during the late Pleistocene. In their opinion, however, this showed a high degree of variability with regard to the morphology of the skull and teeth, for example in the design of the tusks and molars. Following the priority rule of the ICZN, the valid generic name assigned to this gomphotheria representative is Notiomastodon , the only species included is to be named Notiomastodon platensis . The view was repeated several times in the following years, also presented Mothé and fellow researchers through extensive dental and skelettmorphologische analysis found that stegomastodon significantly from notiomastodon departed and was restricted to North America. Spencer George Lucas later adopted the concept.

Amahuacatherium

The genus Amahuacatherium , which was described by Lidia Romero-Pittman in 1996 using a mandibular fragment and two isolated molars from the Madre de Dios region in southeastern Peru , is problematic . The finds came to light in the Ipururo Formation , which is exposed along the Río Madre de Dios . A partial skeleton discovered together with the finds was lost in a violent flood. The author highlighted the short lower jaw with alveoli for rudimentary tusks and molars with a moderately complex occlusal surface pattern as a special feature of Amahuacatherium . The age of the sedimentary layers with the fossil remains is estimated at around 9.5 million years, which corresponds to the Upper Miocene . This would make Amahuacatherium one of the first mammals to make their way from North to South America before the Great American Fauna Exchange , which only started around six million years later. In addition, the finds would be much older than the next oldest evidence of gomphotheria in both Central and South America, which are 7 and 2.5 million years old, respectively. Only a few years later, various authors expressed doubts about the genre and age. The molars were seen as hardly distinguishable from other South American gomphotheries and the presence of alveoli for the mandibular tusks as a misinterpretation of mandibular cavities. The geological age was also difficult to determine due to the complex stratigraphic conditions. Other scientists agreed, and further dental examinations did not reveal any significant differences to notiomastodon compared to other South American findings .

literature

- Marco P. Ferretti: Anatomy of Haplomastodon chimborazi (Mammalia, Proboscidea) from the late Pleistocene of Ecuador and its bearing on the phylogeny and systematics of South American gomphotheres. Geodiversitas 32 (4), Florenz 2010, pp. 663-721, doi: 10.5252 / g2010n4a3

- Dimila Mothé, Leonardo dos Santos Avilla, Lidiane Asevedo, Leon Borges-Silva, Mariane Rosas, Rafael Labarca-Encina, Ricardo Souberlich, Esteban Soibelzon, José Luis Roman-Carrion, Sergio D. Ríos, Ascanio D. Rincon, Gina Cardoso de Oliveira and Renato Pereira Lopes: Sixty years after 'The mastodonts of Brazil': The state of the art of South American proboscideans (Proboscidea, Gomphotheriidae). Quaternary International 443, 2017, pp. 52-64

- Dimila Mothé, Marco P. Ferretti and Leonardo S. Avilla: Running Over the Same Old Ground: Stegomastodon Never Roamed South America. Journal of Mammalian Evolution 26 (2), 2019, pp. 165-177

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Marco P. Ferretti: Anatomy of Haplomastodon chimborazi (Mammalia, Proboscidea) from the late Pleistocene of Ecuador and its bearing on the phylogeny and systematics of South American gomphotheres. Geodiversitas 32 (4), Florenz 2010, pp. 663-721, doi: 10.5252 / g2010n4a3

- ↑ Asier Larramendi: Shoulder height, body mass, and shape of proboscideans. Acta Palaeontologia Polonica 61 (3), 2016, pp. 537-574

- ^ Richard A. Fariña, Sergio F. Vizcaíno and María S. Bargo: Body mass estimations in Lujanian (Late Pleisticene-Early Holocene of South America) mammal megafauna. Mastozoología Neotropical 5 (2), 1998, pp. 87-108

- ^ Per Christiansen: Body size in proboscideans, with notes on elephant metabolism. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 140, 2004, pp. 523-549

- ↑ a b c María Teresa Alberdi, Esperanza Cerdeño and José Luis Prado: Stegomastodon platensis (Proboscidea, Gomphotheriidae) en el Pleistoceno de Santiago del Estero, Argentina. Ameghiniana 45 (2), 2008, pp. 257-271

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Dimila Mothé, Marco P. Ferretti and Leonardo S. Avilla: Running Over the Same Old Ground: Stegomastodon Never Roamed South America. Journal of Mammalian Evolution 26 (2), 2019, pp. 165-177

- ↑ a b c d Spencer George Lucas and Guillermo E. Alvarado: Fossil Proboscidea from the Upper Cenozoic of Central America: Taxonomy, evolutionary and paleobiogeographic significance. Revista Geológica de América Central 42, 2010, pp. 9-42

- ↑ a b c d e Spencer G. Lucas: The palaeobiogeography of South American gomphotheres. Journal of Palaeogeography 2 (1), 2013, pp. 19-40, doi: 10.3724 / SP.J.1261.2013.00015

- ↑ a b c Dimila Mothé, Marco P. Ferretti and Leonardo S. Avilla: The Dance of Tusks: Rediscovery of Lower Incisors in the Pan-American Proboscidean Cuvieronius hyodon Revises Incisor Evolution in Elephantimorpha. PLoS ONE 11 (1), 2016, p. E0147009, doi: 10.1371 / journal.pone.0147009

- ↑ a b c d George Gaylord Simpson and Carlos de Paula Couto: The mastodons of Brazil. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 112, 1957, pp. 131-189

- ↑ a b c d e f g Dimila Mothé and Leonardo Avilla: Mythbusting evolutionary issues on South American Gomphotheriidae (Mammalia: Proboscidea). Quaternary Science Reviews 110, 2015, pp. 23-35

- ↑ a b c Spencer George Lucas, Ricardo H. Aguilar and Justina Spillmann: Stegomastodon (Mammalia, Proboscidea) from the Pliocene of Jalisco, Mexico and the species-level taxonomy of Stegomastodon. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 53, 2011, pp. 517-553

- ↑ José Luis Prado, María Teresa Alberdi, Begoña Sánchez and Beatriz Azanza: Diversity of the Pleistocene Gomphotheres (Gomphotheriidae, Proboscidea) from South America. Deinsea 9, 2003, pp. 347-363

- ↑ a b c d José Luis Prado, Maria Teresa Alberdi, Beatriz Azanza, Begonia Sánchez and Daniel Frassinetti: The Pleistocene Gomphotheriidae (Proboscidea) from South America. Quaternary International 126-128, 2005, pp. 21-30

- ↑ María Teresa Alberdi and José Luis Prado: Presencia de Stegomastodon (Gomphotheriidae, Proboscidea) en el Pleistoceno Superior de la zona costera de Santa Clara del Mar (Argentina). Estudios Geológicos 64 (2), 2008, pp. 175-185

- ↑ Dimila Mothé, Willer Flores Aguanta, Sabrina Larissa Belatto and Leonardo Avilla: First record of Notiomastodon platensis (Mammalia, Proboscidea) from Bolivia. Revista brasileira de Paleontologia 20 (1), 2017, pp. 149–152

- ^ A b c D. Frassinetti and María Teresa Alberdi: Presencia del género Stegomastodon entre los restos fósiles de mastodontes de Chile (Gomphotheriidae), Pleistoceno Superior. Estudios Geológicos 61 (1-2), 2005, pp. 101-107

- ↑ a b c d Rafael Labarca Encina and María Teresa Alberdi: An updated taxonomic view on the family Gomphotheriidae (Proboscidea) in the final Pleistocene of south-central Chile. New Yearbook for Geology and Paleontology Essays 262 (1), 2011, pp. 43–57

- ↑ a b Renato Pereira Lopes, Luiz Carlos Oliveira, Ana Maria Graciano Figueiredo, Angela Kinoshita, Oswaldo Baffa and Francisco Sekiguchi Buchmann: ESR dating of pleistocene mammal teeth and its implications for the biostratigraphy and geological evolution of the coastal plain, Rio Grande do Sul , southern Brazil. Quaternary International 212, 2010, pp. 213-222

- ↑ Alexsandro Schiller Aires and Renato Pereira Lopes: Represantivity of Quaternary mammals from the Southern Brazilian continental shelf. Revista brasileira de Paleontologia 15 (1), 2012, pp. 57-66

- ↑ a b Dimila Mothé, Leonardo S. Avilla and Gisele R. Wick: Population structure of the gomphothere Stegomastodon waringi (Mammalia: Proboscidea: Gomphotheriidae) from the Pleistocene of Brazil. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências 82 (4), 2010, pp. 983-996

- ↑ a b c Lidiane Asevedo, Gisele R. Winck, Dimila Mothé and Leonardo S. Avilla: Ancient diet of the Pleistocene gomphothere Notiomastodon platensis (Mammalia, Proboscidea, Gomphotheriidae) from lowland mid-latitudes of South America: Stereomicrowear and tooth calculus analyzes combined . Quaternary International 255, 2012, pp. 42-52

- ↑ a b c Giovanni Ficcarelli, Vittorio Borselli, Miguel Moreno Espinosa and Danilo Torre: New haplomastodon finds from the Late Pleistocene of Northern Ecuador. Geobios 26 (2), 1993, pp. 231-240

- ^ A b María Teresa Alberdi, Madrid, José Luis Prado and Rodolfo Salas: The Pleistocene Gomphotheriidae (Proboscidea) from Peru. New yearbook for geology and palaeontology treatises 231 (3), 2004, pp. 423–452

- ↑ Jorge B. Carrillo, Edwin A. Chavez and Imerú H. Alfonzo: Notas preliminares sobre los Mastodontes Gonfoterios (Mammalia: Proboscidea) del cuaternario venezolano. Boletín Antropológico 26 (7), 2008, pp. 233-263

- ↑ a b Francisco Javier Aceituno and Sneider Rojas-Mora: Lithic technology studies in Colombia during the Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene. Chungara, Revista de Antropología Chilena 47 (1), 2015, pp. 13-23

- ↑ a b Brunella Muttillo, Giuseppe Lembo, Ettore Rufo, Carlo Peretto and Roberto Lleras Pérez: Revisiting the oldest known lithic assemblages of Colombia: A review of data from El Abra and Tibitó (Cundiboyacense Plateau, Eastern Cordillera, Colombia). Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 13, 2017, pp. 455-465

- ^ Emily L. Lindsay and Eric X. Lopez R .: Tanque Loma, an new Late Pleistocene megafaunal tar seep locality from southwest Ecuador. Journal of South American Earth Sciences 57, 2015, pp. 61-82

- ↑ Emily L. Lindsay and Kevin L. Seymour, "Tar pits" of the Western Neotropics: Paleoecology, Taphonomy, and Mammalian Biogeography. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Science Series 42, 2015, pp. 111-123

- ↑ José Luis Prado, María Teresa Alberdi, B. Azanza, Begoña Sánchez and D. Frassinetti: The Pleistocene Gomphotheres (Proboscidea) from South America: diversity, habitats and feeding ecology. In: G. Cavarretta, P. Gioia, M. Mussi and MR Palombo (eds.): The World of Elephants - International Congress. Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche Rome, 2001, pp. 337-340

- ↑ Begoña Sánchez, José Luis Prado and María Teresa Alberdi: Feeding ecology, dispersal, and extinction of South American Pleistocene gomphotheres (Gomphotheriidae, Proboscidea). Paleobiology 30 (1), 2004, pp. 146-161

- ↑ Fernando Henrique de Souza Barbosa, Kleberson de Oliveira Porpino, Ana Bernadete Lima Fragoso and Maria de Fátima Cavalcante Ferreira dos Santos: Osteomyelitis in Quaternary mammal from the Rio Grande do Norte State, Brazil. Quaternary International 299, 2013, pp. 90-93

- ↑ Fernando Henrique de Souza Barbosa, Hermínio Ismael de Araújo-Júnior, Dimila Mothé and Leonardo dos Santos Avilla: Osteological diseases in an extinct Notiomastodon (Mammalia, Proboscidea) population from the Late Pleistocene of Brazil. Quaternary International 443, 2017, pp. 228-232, doi: 10.1016 / j.quaint.2016.08.019

- ↑ Victor Hugo Dominato, Dimila Mothé, Leonardo dos Santos Avilla and Cristina Bertoni-Machado: Ação de insetos em vértebras cervicais Stegomastodon waringi (Gomphotheriidae: Mammalia) do Pleistoceno de Águas de Araxá, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia 12 (1), 2009, pp. 77-82

- ↑ Victor Hugo Dominato, Dimila Mothé, Rafael Costa da Silva and Leonardo dos Santos Avilla: Evidence of scavenging on remains of the gomphothere Haplomastodon waringi (Proboscidea: Mammalia) from the Pleistocene of Brazil: Taphonomic and paleoecological remarks. Journal of South American Earth Sciences 31, 2011, pp. 171-177

- ↑ Rafael Labarca, Omar Patricio Recabarren, Patricia Canales-Brellenthin and Mario Pino: The gomphotheres (proboscidea: Gomphotheriidae) from Pilauco site: Scavenging evidence in the Late Pleistocene of the Chilean Patagonia. Quaternary International 352, 2014, pp. 75-84

- ^ Joseph J. El Adli, Daniel C. Fisher, Michael D. Cherney, Rafael Labarca and Frédéric Lacombat: First analysis of life history and season of death of a South American gomphothere. Quaternary International 443, 2017, pp. 180-188

- ↑ Silvia A. Aramayo, Teresa Manera de Bianco, Nerea V. Bastianelli and Ricardo N. Melchor: Pehuen Co: Updated taxonomic review of a late Pleistocene ichnological site in Argentina. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 439, 2015, pp. 144-165

- ↑ Mario A. Cozzuol, Dimila Mothé and Leonardo S. Avilla: A critical appraisal of the phylogenetic proposals for the South American Gomphotheriidae (Proboscidea: Mammalia). Quaternary International 255, 2012, pp. 36-41

- ↑ Jehezekel Shoshani, Robert C. Walter, Michael Abraha, soap Berhe, Pascal Tassy, William J. Sander, Gary H. Marchant, Yosief Libsekal, Tesfalidet Ghirmai and Dietmar Zinner: A proboscidean from the late Oligocene of Eritrea, a '' missing link '' between early Elephantiformes and Elephantimorpha, and biogeographic implications. PNAS 103 (46), 2006, pp. 17296-17301

- ↑ a b Jeheskel Shoshani and Pascal Tassy. Advances in proboscidean taxonomy & classification, anatomy & physiology, and ecology & behavior. Quaternary International 126-128, 2005, pp. 5-20

- ↑ Malcolm C. McKenna and Susan K. Bell: Classification of mammals above the species level. Columbia University Press, New York, 1997, pp. 1-631 (pp. 497-504)

- ^ William J. Sanders, Emmanuel Gheerbrant, John M. Harris, Haruo Saegusa and Cyrille Delmer: Proboscidea. In: Lars Werdelin and William Joseph Sanders (eds.): Cenozoic Mammals of Africa. University of California Press, Berkeley, London, New York, 2010, pp. 161-251

- ^ Jan van der Made: The evolution of the elephants and their relatives in the context of a changing climate and geography. In: Harald Meller (Hrsg.): Elefantenreich - Eine Fossilwelt in Europa. Halle / Saale 2010, pp. 340-360

- ↑ José Luis Prado and María Teresa Alberdi: A cladistic analysis among trilophodont gomphotheres (Mammalia, Proboscidea) with special attention to the South American genera. Palaeontology 51 (4), 2008, pp. 903-915

- ^ A b María Teresa Alberdi and José Luis Prado: Fossil Gomphotheriidae from Argentina. In: FL Agnolin, GL Lio, F. Brisson Egli, NR Chimento and FE Novas (eds.): Historia Evolutiva y Paleobiogeogr afica de los Vertebrados de Am erica del Sur. Contribuciones del MACN 6, Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales “Bernardino Rivadavia”, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2016, pp. 275–283

- ↑ Wang Yuan, Jin Chang-Zhu, Deng Cheng-Long, Wei Guang-Biao and Yan Ya-Ling: The first Sinomastodon (Gomphotheriidae, Proboscidea) skull from the Quaternary in China. Chinese Science Bulletin 57 (36), 2012, pp. 4726-4734

- ↑ a b Michael Buckley, Omar P. Recabarren, Craig Lawless, Nuria García and Mario Pino: A molecular phylogeny of the extinct South American gomphothere through collagen sequence analysis. Quaternary Science Reviews 224, 2019, p. 105882, doi: 10.1016 / j.quascirev.2019.105882

- ↑ Nadin Rohland, Anna-Sapfo Malaspinas, Joshua L. Pollack, Montgomery Slatkin, Paul Matheus and Michael Hofreiter: Proboscidean Mitogenomics: Chronology and Mode of Elephant Evolution Using Mastodon as Outgroup. PLoS Biology 5 (8), 2007, pp. 1663-1671, doi: 10.1371 / journal.pbio.0050207

- ↑ M. Buckley, N. Larkin and M. Collins: Mammoth and Mastodon collagen sequences; survival and utility. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 75, 2011, pp. 2007-2016

- ↑ Matthias Meyer, Eleftheria Palkopoulou, Sina Baleka, Mathias Stiller, Kirsty EH Penkman, Kurt W. Alt, Yasuko Ishida, Dietrich Mania, Swapan Mallick, Tom Meijer, Harald Meller, Sarah Nagel, Birgit Nickel, Sven Ostritz, Nadin Rohland, Karol Schauer, Tim Schüler, Alfred L Roca, David Reich, Beth Shapiro, Michael Hofreiter: Palaeogenomes of Eurasian straight-tusked elephants challenge the current view of elephant evolution. eLife Sciences 6, 2017, p. e25413, doi: 10.7554 / eLife.25413

- ↑ a b c d Dimila Mothé, Leonardo dos Santos Avilla, Lidiane Asevedo, Leon Borges-Silva, Mariane Rosas, Rafael Labarca-Encina, Ricardo Souberlich, Esteban Soibelzon, José Luis Roman-Carrion, Sergio D. Ríos, Ascanio D. Rincon , Gina Cardoso de Oliveira and Renato Pereira Lopes: Sixty years after 'The mastodonts of Brazil': The state of the art of South American proboscideans (Proboscidea, Gomphotheriidae). Quaternary International 443, 2017, pp. 52-64

- ↑ MA Reguero, AM Candela and RN Alonso: Biochronology and biostratigraphy of the Uquı'a Formation (Pliocene-early Pleistocene, NW Argentina) and its significance in the Great American Biotic Interchange. Journal of South American Earth Sciences 23, 2007, pp. 1-16

- ^ A b María Teresa Alberdi and José Luis Prado: Los mastodontes de América del Sur. In: M. T Alberdi, G. Leone and EP Tonni (eds.): Evolución biológica y climática de la Región Pampeana durante los últimos 5 millones de años. An ensayo de correlación with the Mediterráneo occidental. Monografías Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, CSIC, Spain, 1995, pp. 277-292

- ^ Alan J. Bryan, Rodolfo M. Casamiquela, José M. Cruxent, Ruth Gruhn and Claudio Ochsenius: An El Jobo Mastodon Kill at Taima-Taima, Venezuela. Science 200, 1978, pp. 1275-1277

- ↑ Ruth Gruhn and Alan J. Bryan: The record of Pleistocene megafaunal extinction at Taima-taima, Northern Venezuela. In: Paul S. Martin and Richard G. Klein (Eds.): Quaternary Extinctions. A Prehistoric Revolution. The University of Arizona Press, Tucson AZ, 1984, pp. 128-137

- ^ Luis Alberto Borrero: Extinction of Pleistocene megamammals in South America: The lost evidence. Quaternary International 185, 2008, pp. 69-74

- ↑ Mauro Coltorti, Jacopo Della Fazia, Freddy Paredes Rios and Giuseppe Tito: Ñuagapua (Chaco, Bolivia): Evidence for the latest occurrence of megafauna in association with human remains in South America. Journal of South American Earth Sciences 33, 2012, pp. 56-67

- ^ José Luis Prado, Joaquín Arroyo-Cabrales, Eileen Johnson, María Teresa Alberdi and Oscar J. Polaco: New World proboscidean extinctions: comparisons between North and South America. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 7, 2015, pp. 277-288, doi: 10.1007 / s12520-012-0094-3

- ↑ Georges Cuvier: Sur différentes dents du genre des mastodontes, mais d'espèces moindres que celle de l'Ohio, trouvées en plusieurs lieux des deux continents. Annales du Museum d'Histoire naturelle 8, 1806, pp. 401–420 ( [1] )

- ↑ Gotthelf Fischer: Zoognosia · - tabulis synopticis illustrata. Moscow, 1814, pp. 1–694 (pp. 337–341) ( [2] )

- ↑ Georges Cuvier: Recherches sur les ossemens fossiles. Nouvelle édition. Tome 5 (2). Paris, 1824, pp. 1–547 (p. 527) ( [3] )

- ↑ Florentino Ameghino: Contribución al conocimiento de los mamíferos fósiles de la República Argentina. Academia Nacional Ciencias (Córdoba) 6, 1889, pp. 1–1027 (pp. 633–650) ( [4] )

- ^ Henry Fairfield Osborn: New subfamily, generic, and specific stages in the evolution of the Proboscidea. American Museum Novitates 99, 1923, pp. 1-4

- ^ Henry Fairfield Osborn: Additional new genera and species of the mastodontoid Proboscidea. American Museum Novitates 238, 1926, pp. 1-16

- ↑ Angel Cabrera: Una revisión de los Mastodontes Argentinos. Revista del Museo de La Plata 32, 1929, pp. 61–144 ( [5] )

- ↑ Hans Pohlig: Sur une vieille mandibule de Tetracaulodon ohioticum Blum, avec defense in situ. Bulletin de la Société belge de géologie, de paleontologie et d'hydrologie 26, 1912, pp. 187–193 ( [6] )

- ↑ Giovanni Ficcarelli, Vittorio Borselli, Gonzalo Herrera, Miguel Moreno Espinosa and Danilo Torre: Taxonomic remarks on the South American mastodonts referred by toHaplomastodon and cuvieronius. Geobios 28 (6), 1995, pp. 745-756

- ^ WJ Holland: Fossil mammal collected at Pedra Vernelha, Bahia, Brazil, by GA Waring. Annals of the Carnegie Museum 13, 1920, pp. 224-232

- ↑ Spencer George Lucas: Mastodon waringi Holland, 1920 (currently Haplomastodon waringi; Mammalia, Proboscidea): proposed conservation of usage by designation of a neotype. Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature 66 (2), 2009, pp. 164–167 ( [7] )

- ↑ Marco P. Ferretti: A review of South American gomphotheres. New Mexico Natural History and Science Museum Bulletin 44, 2008, pp. 381-391

- ↑ Spencer George Lucas: Taxonomic nomenclature of Cuvieronius and Haplomastodon, proboscideans from the Plio-Pleistocene of the New World. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 44, 2008, pp. 409-415

- ↑ Dimila Mothé, Leonardo S. Avilla, Mário Cozzuol and Gisele R. Winck: Taxonomic revision of the Quaternary gomphotheres (Mammalia: Proboscidea: Gomphotheriidae) from the South American lowlands. Quaternary International 276, 2012, pp. 2-7

- ↑ Dimila Mothé, Leonardo S. Avilla and Mario A. Cozzuol: The South American Gomphotheres (Mammalia, Proboscidea, Gomphotheriidae): Taxonomy, Phylogeny, and Biogeography. Journal of Mammalian Evolution 20, 2013, pp. 23-32

- ↑ Kenneth E. Campbell, Jr., Carl D. Frailey and Lidia Romero-Pittman: In defense of Amahuacatherium (Proboscidea: Gomphotheriidae). New Yearbook for Geology and Paleontology Essays 252 (1), 2009, pp. 113–128