Operation Entebbe

The Operation Entebbe , Operation Thunderbolt or Operation Yonatan was a military rescue operation on the night of July 4, 1976 on the Entebbe airport in Uganda , with the Israeli security forces, the week-long kidnapping of a passenger plane of Air France ended by Palestinian and German terrorists.

The Israeli elite soldiers were flown in undetected to Entebbe , where they only stayed for a total of 90 minutes. 102 mostly Israeli hostages, including the Air France crew, were finally flown to Israel after a stopover in Kenya. All seven hostage-takers present were killed during the rescue operation. Three of the last 105 hostages, around 20 Ugandan soldiers and Lieutenant Colonel Yonatan Netanyahu of the Israeli forces were killed in firefights. The hostage Dora Bloch , who was left behind in a hospital in the nearby capital Kampala , was later kidnapped and murdered by Ugandan officials.

In retaliation for Kenya's support for the Israeli liberation action, the dictator Idi Amin murdered several hundred Kenyans living in Uganda. The local Ugandan authorities had supported the terrorists, and Amin personally greeted them upon their arrival. Of the 253 passengers, all 77 Israeli and five other hostages were singled out by the terrorists, while the rest but ten young French were released.

A broader debate about the relationship of the left to anti-Zionism , anti-Semitism and the left-wing terrorist organizations RAF and Revolutionary Cells did not occur until much later in Germany. The action sparked debates in the UN Security Council and raised questions of international law.

Aircraft hijacking

On the morning of June 27, 1976, Air France flight 139 , which was supposed to run from Tel Aviv via Athens to Paris , was hijacked after taking off from Athens. The Airbus A300 , with a crew of 12 and 258 passengers, was diverted to Benghazi Airport in Libya , where it stayed for more than six hours. One passenger inflicted a bleeding abdominal injury and alleged acute pregnancy complications, whereupon the aerial pirates released her as the only hostage in Benghazi. The aircraft was refueled and took off without the pilot being informed of the destination. After a five-hour flight, it finally landed on the morning of June 28 at Entebbe Airport near Kampala, the capital of Uganda .

The hijackers were two terrorists from the group " Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine - External Operations " ( PFLP-EO ), which was led between 1968 and 1977 by Wadi Haddad, who was responsible for numerous aircraft hijackings and has been since In 1972, Wilfried Böse and Brigitte Kuhlmann , two founding members of the Revolutionary Cells , acted independently of the PFLP leadership . They named their unit in honor of the PFLP fighter Mohammad al-Aswad (1946–1973) killed in battle with Israeli soldiers "Guevara Command (of) Gaza". The quartet, who boarded in Athens together with other passengers, were armed with firearms, hand grenades and explosives carried in their hand luggage. The head of the command was Böse, who introduced himself to the passengers from the cockpit under the code name "Basil al-Kubaisy" (after a PFLP leader murdered in 1973) as the new captain of the aircraft, which has now been renamed Haifa . According to an Israeli hostage, the coastal city, which became part of Israel in 1948, was the birthplace of one of the two Palestinian kidnappers and the home of Haddad. At Entebbe airport, the four hijackers were joined by other armed fighters from the PFLP-EO. Fais Jaber - Haddad's close confidante since the founding of the PFLP - took over command from Böse.

The extent to which Idi Amin , who came to power in 1971 with Israeli help and who had turned into a harsh critic of Israel in 1972, acted not just as a spontaneous mediator, but as an initiated supporter of the hostage-takers, is controversial. Israel later accused Amin that before the Air France plane arrived, five terrorists had been flown to Entebbe in his personal plane as reinforcements. Amin himself stated that he had not been informed in advance about the hostage-taking and that he had given the landing permit for humanitarian reasons in view of an otherwise impending crash due to lack of fuel. An analysis of files from the French embassy in Uganda, made by journalists from the newspaper Le Monde , which were released in 2016 after a 40-year embargo, supports this position. On the other hand, several hostages interpreted the fact that the terrorists were able to increase their numbers, supply additional weapons and move freely in the presence of numerous Ugandan soldiers on the airport premises as an indication of prior arrangement.

The hijacking of the airplane was intended to blackmail a total of 53 prisoners from prisons in Israel , France , the Federal Republic of Germany and Switzerland . These included members of the Red Army Faction , the June 2nd Movement and Kōzō Okamoto of the Japanese Red Army . The hijackers also asked the French government to return the aircraft for five million US dollars.

Separation of the Jewish from the non-Jewish hostages

The passengers were held hostage in the old transit hall of the Entebbe terminal . The terrorists “selected” the Jewish passengers from the others. In addition to the Israeli citizens, there were 22 French , one stateless person and the American couple Karfunkel, of Hungarian-Jewish origin. The remaining hostages were released. The remaining hostages without an Israeli passport were identified as Jews - sometimes incorrectly - based on their supposedly Jewish names or other evidence. This selection was adopted by the German terrorists Böse and Kuhlmann. When a Holocaust survivor showed Böse his tattooed prisoner number and thus reminded him of the selection in the concentration camps , Böse replied to the implied allegation that he was not a Nazi, but an idealist .

Due to the announcement by the hijackers that the flight crew and initially 47 of the non-Israeli passengers would be released and would be allowed to transfer to another Air France aircraft, one flew to Entebbe. Michel Bacos , the hijacked flight captain of Flight 139, first discussed it with the 11 members of his crew and then announced to Böse that all passengers were under his responsibility, which is why he and the crew could not leave any passengers behind, but had to stay with them, which Böse accepted . Bacos was later awarded the Legion of Honor by the French President and received honors from the State of Israel and various Jewish organizations. The other members of the flight crew were also honored. A French nun also refused to leave and wanted to take the place of a Jewish hostage, but was forced into the waiting Air France plane by Ugandan soldiers.

Liberation operation by the Israeli military

Preparations

The Israeli military and the Mossad collected information for several days in Israel and on the ground, as well as in Paris from the released hostages . Entebbe Airport had been expanded a few years earlier by an Israeli company, which is why plans for the facility were available. The released hostages were questioned intensively. The most valuable source turned out to be a French-Jewish former army officer who remembered essential details of the buildings, the kidnappers, their armament and their cooperation with the Ugandan armed forces.

The Israelis drew up plans to intervene and rebuilt parts of the hall. Finally, four Israeli Hercules transport planes, accompanied by phantom jets of the Israeli air force, flew low to Entebbe and landed at the airport at night. They were followed by two Boeing 707s , one as an operations center, the other with medical facilities, which flew to Nairobi airport in Kenya .

The task force of around a hundred men consisted of a staff unit led by Brigadier General Dan Schomron and associated communication and support troops, an intervention force of 29 men led by Lieutenant Colonel Netanyahu , including soldiers from the Sajeret Matkal in various groups under Major Moshe Betser and Matan Vilnai and a reinforcement force that was responsible for securing the area, destroying the Ugandan air force's MiG fighters , securing the takeover of the hostages and refueling the aircraft.

Course of action

The first aircraft identified itself via radio as a scheduled aircraft that was actually expected a little later at the airport; so it could initially land undetected and roll into a remote part of the airfield. The Lufthansa had a scheduled flight canceled, the Ugandan government of the West German Embassy in Kampala which is why after the action complicity accused.

At 1 o'clock a black Mercedes and some Land Rover were unloaded under cover of darkness. The aim was to simulate the landing of a high-ranking Ugandan official or amine himself. The Israeli command, imitating a column of Amins cars, drove straight to the main building. During this trip, two Ugandan guards who tried to stop the vehicles were shot. Ugandan troops, in turn, opened fire on the Israelis who stormed the airport building, killing Lieutenant Colonel Yonatan Netanyahu , a brother of later Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu .

Armored vehicles were unloaded from other cargo aircraft, which landed only minutes later, with which the return route was secured and the Ugandan soldiers were fought on the spot. The commando, disguised in Ugandan uniforms, quickly entered the main building where the 105 hostages were being held. The Israeli fighters stormed the building and shot everyone standing as ordered. When the exchange of fire began, the hostage-takers were killed, but three hostages also died in the exchange of fire. The fighting lasted less than an hour. At least twenty Ugandan soldiers, all seven terrorists, three hostages and one Israeli officer were killed. In addition to a few Mossad employees, mainly over a hundred Sajeret Matkal elite soldiers were involved in the action.

Since the planes had to be refueled to reach Israel, pumps were on board to tap the Ugandan kerosene tanks. It was only in Entebbe that the pilots received the news that the Kenyan authorities had given them permission to make a stopover in Nairobi . There were 11 Ugandan MiG fighter jets on the airfield, around a quarter of the Ugandan Air Force, which were destroyed. The freed 102 hostages were then flown to Israel via Nairobi. In Kenya, the Israelis had a regular stopover, the medical treatment of some hostages by Israeli doctors and the refueling of the planes.

designation

The military action, usually named after the place where it happened, has no uniform name in German. In Israel, the action was originally codenamed thunderclap (כדור הרעם, Kadur hara'am, English literally "Thunderball", but more often "Thunderbolt"), was subsequently but in honor of doing who died commander Yonatan Netanyahu officially in operation Yonatan (מבצע יונתן, mivtsa yonatan) renamed.

consequences

The Israeli hostage Dora Bloch was in a hospital in Kampala at the time of the hostage release; therefore it could not be detected by Operation Entebbe. She was killed by Ugandan officials on Amin's orders the following day; Doctors and nurses who stood up for them were also murdered. Furthermore, Amin had several hundred Kenyans in Uganda killed because he assumed that Kenya had cooperated with the Israelis.

The hijacked aircraft was not immediately released by the Ugandan authorities, but was finally transferred to Paris on July 22, 1976 by an Air France crew who had flown in for this purpose, after President Amin had announced the return the day before. Eleven projectiles were struck in the fuselage of the Airbus during the firefight at Entebbe airport, but this did not affect its ability to fly.

International law issues

In the UN Security Council, the Afro-Arab and socialist states had called for a special session because of the violation of Uganda's sovereignty. The UN Secretary General Kurt Waldheim condemned the action as a "serious violation of the sovereignty of a member state."

With its support for the terrorists, the Ugandan government, which was never recognized by some states such as Tanzania, violated the ICAO Hague Convention on Combating the Unlawful Occupation of Aircraft and the minimum requirements for dealing with foreign nationals. Most of the western-oriented states, with the exception of Japan, tolerated the action. An explicit condemnation of Israel did not find a majority in the Security Council. Ambassador Chaim Herzog defended the commitment, of which one is justifiably proud, before the UN Security Council as an expression of the values for which Israel stands, for human dignity, human life and human freedom as such.

We come with a simple message to the Council: we are proud of what we have done because we have demonstrated to the world that in a small country, in Israel's circumstances, with which the members of this Council are by now all too familiar, the dignity of man, human life and human freedom constitute the highest values. We are proud not only because we have saved the lives of over a hundred innocent people — men, women and children — but because of the significance of our act for the cause of human freedom.

"We come with a simple message to the Security Council: We are proud of what we have done because we have shown the world that in a small country, in the situation of Israel, which is now all too familiar to the members of this Council, human dignity, human life and human freedom represent the highest values. We are proud not only because we saved the lives of over a hundred innocents - men, women and children - but because of the importance of our actions for the cause of human freedom. "

According to the lawyer Ulrich Beyerlin , the actions of the Israeli armed forces in the absence of an armed attack by Uganda against Israel were not covered by the right to self-defense in the event of war. Similar to the Caroline / McLeod affair or Operation Dragon Rouge and Dragon Noir , Operation Entebbe raises the question of the compatibility of a state's military protective measures for the benefit of its citizens attacked abroad with international law and other legal claims below the threshold of war.

Reception and impact history

For many Germans, the action in Entebbe led to a prolonged enthusiasm for Israel. Formulations such as Blitzkrieg were used, the reference to which the German military would have been taboo in Germany itself and which therefore later caused offense. The unrestricted and sustained support at government level contributed to a significant improvement and consolidation of official government relations between the Federal Republic of Germany and Israel, while Israeli relations with the GDR continued to deteriorate.

In 1976, German commentators stressed the considerable pressure that the West German authorities were under in view of their responsibility for the Jewish hostages threatened by German terrorists. It was speculated to what extent the Federal Republic could have avoided the German prisoners being pressed free without the Israeli intervention without significant loss of face.

Die Zeit spoke of a "hardly repeatable stroke of luck" for the Federal Republic:

“The federal government got off the hook just as happily. Her subsequently published declaration of intent that she would not release any terrorist imprisoned in this country in exchange for Israeli hostages could only be kept under the premise of the success of the liberation operation. What would we have done, what should we have done if Israel had been compelled to release forty Palestinians imprisoned in order to rescue its hostages? Would we have refused an exchange à la Peter Lorenz at the expense of the lives of the Jews, whom a German terrorist had previously selected from others at gunpoint, just so as not to have to give up five Baader Meinhof people in German prisons? We would hardly have endured "

Der Spiegel , on the other hand, offered a purely "strategic" explanation :

“The kidnappers skilfully took into account the special relationship that unites Germans and Jews. Once they saw the world's attention drawn to their action, they demonstrated generosity and released the majority of the hostages. By de-escalation, they hoped to be able to persuade the other side to compromise as well. At the same time, however, they held back all Jewish passengers. And they apparently calculated exactly that Bonn would have to respond to their request for the release of six West German prisoners. Because neither in domestic politics nor in front of the global public could the Germans, with their past, afford to bear responsibility for the murder of Jews again.

In contrast, in 1972 the Federal Republic of Germany flew the terrorists, who had survived the hostage-taking in Munich , from Germany to Tripoli against considerable Israeli protests after an airplane was hijacked. In 1977 the federal government was willing and able to bring about a violent solution to the hostage drama in Mogadishu and was no longer willing to release prisoners who had been sentenced by taking them hostage. For this, the experience had helped from the Operation Entebbe, which by his own admission, the former BGS -Beamte Ulrich Wegener , the first commander of the GSG 9 had supported administratively.

Playback in the media

The events in Entebbe were immediately taken up in literature and film. Just eight days after release of the hostages, the Israeli publishing house published Keter-Press with surgery Uganda by Uri Dan , the first book with a circulation of 5,000 copies. Also in July 1976 the American publisher Bantam Books published the book 90 minutes in Entebbe by William Stevenson in the USA with an initial circulation of 330,000 copies, in which Uri Dan is sometimes named as a co-author. A total of seven books had been published by the end of the year, some of which were also translated into various other languages. Stevenson's work was published in a German translation by Ullstein-Verlag in the summer of 1976 . With Victory at Entebbe also still in 1976 the first feature film was released in theaters worldwide. The next year, another Hollywood production followed with ... who know no mercy (original title: Raid on Entebbe ) . Also in 1977 was the Israeli production Operation Thunderbolt (original title: Mivtsa Jonatan ) by Menahem Golan . The actors Shimon Peres , Jigal Allon and Jitzchak Rabin played themselves as actors, which underlined the claim to the documentary character.

At the same time, after the Six Day War in 1967 and the Yom Kippur War in 1973, the threat to Israel resulted in the Holocaust being more closely integrated into the founding myth of the State of Israel and in the international media. This led to a stronger thematization of the extermination of the Jews in the international media and film productions and was also thematized in the cinematic reproductions of Operation Entebbe. In all of the film adaptations, Böse was portrayed by a German actor with an appropriate accent, the selection of the Jewish (not the Israeli) hostages, including a Holocaust survivor, interpreted by German terrorists as the key scene.

In the 1970s, air travel became increasingly accessible to a broader population, while the number of hijackings rose. While they were initially mostly ended by hostage exchanges, a tendency towards intervention emerged with Entebbe, the occurrence of which, like success, was increasingly welcomed in the western world. In West Germany, Entebbe took a back seat to the Landshut hostage drama and the German autumn . A German cinematic or literary processing only took place later. In 2010 Thomas Ammann shot an ARTE documentary on the topic as well as the WDR documentary Operation Thunderbolt - Israel against German Terrorists , which was shown on ARTE on January 10, 2012.

Commemoration

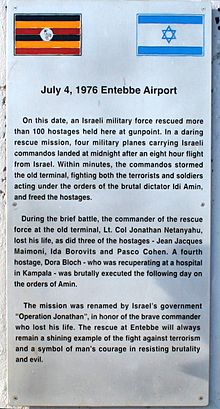

At Entebbe airport, an Israeli-Ugandan plaque on the outer wall of the former terminal building has been commemorating the events and the killed Israeli leader of the operation since 2005.

The Boeing 707 (4X-JYD) used during the operation as a flying command center is on display in the Israeli Air Force Museum.

There was also criticism of the media and official handling of the three hostages who died in the action.

Controversy over the role of Yonatan Netanyahu

From 1986 onwards, protracted public disputes between Moshe Betser and the brothers Iddo and Benjamin Netanyahu broke out in Israel . In retrospect, Betser accused Yonatan Netanyahu, who is now revered as a hero, of needlessly shooting the two guards who, according to his experience in Africa, had not seriously stopped the column, but simply waved through in anticipation of an official, in the entrance area. In doing so, he caused his own death and unnecessarily risked the surprise effect of the action. Netanyahu was only partially present during the preparations, so Betser saw Netanyahu glorified in an exaggerated way. Iddo Netanyahu defended his brother's image with book publications that contradicted the account of Betser, the Historical Commission of the Israel Defense Forces and other historians.

Effects in the left scene

Hans-Joachim Klein , who participated in the OPEC hostage-taking in 1975 as a terrorist of the Revolutionary Cells (RZ) , during which he was involved in the murder of three people, went into hiding shortly afterwards. In 1977 he distanced himself from the data center and warned of planned data center attacks against the prominent Jewish representatives Heinz Galinski and Ignaz Lipinski , heads of the Jewish community in Frankfurt am Main.

Other members of the organization began to publicly self-criticize only in 1991 and in the context of the violent death of a member to question their relationship to the Palestinians:

“Instead of noticing what was held up against us, namely that we as an organization participated in an operation in the course of which Israeli citizens and Jewish passengers of other nationalities had been singled out and taken hostage, we were mainly concerned with the military aspect of the operation and its violent termination. "

The former RAF terrorist Peter-Jürgen Boock stated that, without the help of the Palestinians, both the RZ and the RAF would "have been unable to take action from the mid-1970s to the early 1980s, or only to a limited extent".

No other terrorist act perpetrated by Germans has caused such irritation as the “Selection of Entebbe”. The publicist Henryk M. Broder later described Operation Entebbe as his “private awakening experience” that led to his break with the radical left. Even Joschka Fischer called the "selection" of Entebbe as a decisive factor in its rejection of violence and militancy. This first selection of Jews and non-Jews since the Second World War was reminiscent of Auschwitz around the world , but there was no outcry within the radical left.

German leftists have remained partly anti-Zionist and anti-Israeli until the present day. In 2004, this, including the different reactions to Entebbe, was the subject of a conference on “Anti-Semitism of the Left” in the Hans-Böckler-Foundation.

Audiovisual adaptations

Feature films

- 1976: Entebbe (Victory At Entebbe) , with Richard Dreyfuss , Anthony Hopkins , Burt Lancaster , Elizabeth Taylor . Director: Marvin J. Chomsky . In January 1977 the revolutionary cells carried out an arson attack on an Aachen cinema showing this film.

- 1977:… who know no mercy (Raid On Entebbe) , with Peter Finch , Horst Buchholz , Charles Bronson , Yaphet Kotto . Director: Irvin Kershner

- 1977: Operation Thunderbolt (Mivtsa Yonatan) , with Yehoram Gaon , Sybil Danning , Klaus Kinski . Director: MENAHEM GOLAN

- 2018: 7 Days in Entebbe (7 Days in Entebbe) , with Rosamund Pike , Daniel Brühl , Eddie Marsan . Director: José Padilha

- The film The Last King of Scotland (2006) with Forest Whitaker also deals in some sections with the Entebbe company, in the framework of which the (fictitious) story of the main character was woven into.

Documentation

- Eyal Sher: Operation Thunderbolt: Entebbe (2000), TV documentary (52 min.)

- Michael Greenspan: Against All Odds: Israel Survives - Rescue at Entebbe (2005), (26 min.)

- Nissim Mossek: In the crosshairs of the Mossad. Golda's Vengeance, Entebbe Operation, Operation Sphinx (2006), (142 min.) ( On YouTube )

- Jim Nally: Situation Critical: Assault on Entebbe (2007), TV documentary (48 min.), National Geographic Channel

- Paul Taylor and Steve Condie: Age of Terror. Part 1: Terror International (German title: Age of Terror. Part 1: Operation Entebbe ) (2008), TV documentary (59 min.), BBC

- Thomas Ammann : From Auschwitz to Entebbe: Israel's Fight Against Terror. (2009), TV documentary (50 min.), ZDF / Arte. Slightly shortened version: Operation Thunderbolt: Israel's Fight against Terror (43 min.).

- Eyal Boers: Live or Die in Entebbe (2012), cinema documentary (52 min.), With a thematic focus on the three Israeli hostages shot during the liberation campaign ( trailer , interview with the director )

- Andrew Wainrib: Cohen on the Bridge: Rescue at Entebbe (2012), animated film (20 min.)

- James Hyslop: Assault and Rescue: Operation Thunderball - The Entebbe Raid (2012), TV documentary (43 min.), Discovery Channel Canada

- Talya Tibbon: Black Ops: Operation Entebbe (2012), TV documentary (45 min.), The Military Channel ( on YouTube )

- Michaela Kolster and Martin Priess: Entebbe: The unholy bond of terror. (2018), TV documentary (29 min.), Phoenix ( available online )

Video game

The Japanese computer game company Taito launched Operation Thunderbolt in 1988 , a shoot 'em up inspired by Operation Entebbe . It was originally played on arcade machines and in later years it was sold for various computer game formats.

literature

- Bernhard Blumenau: The United Nations and Terrorism. Germany, Multilateralism, and Antiterrorism Efforts in the 1970s. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke / New York 2014, ISBN 978-1-137-39196-4 , chapter 2.

- Saul David : Operation Thunderbolt. Flight 139 and the Raid on Entebbe Airport. Hodder & Stoughton, London 2015, ISBN 978-1-44476-251-8 .

- Annette Vowinckel : The short way to Entebbe or the extension of German history to the Middle East. In: Zeithistorische Forschungen / Studies in Contemporary History. 1 (2004), issue 2, (online) .

- Shelley Harten: Reenactment of a Trauma. The Entebbe aircraft hijacking in 1976. German terrorists in the Israeli press. Tectum, Marburg 2012, ISBN 978-3-8288-2853-7 .

- Freia Anders, Alexander Sedlmaier: “Entebbe Enterprise” 1976. Perspectives on an airplane hijacking that are critical of sources. (PDF) In: Yearbook for Research on Antisemitism . 22 (2013), pp. 267-290.

- Markus Mohr (Ed.): Legends about Entebbe. An act of air piracy and its dimensions in the political discussion. Unrast, Münster 2016, ISBN 978-3-89771-587-5 .

Web links

- Ben Porat, Eitan Haber, Zeev Ship: Top Secret - Thunderball Company: The Liberation of Hostages in Entebbe. Series. In: Der Spiegel , 44,45,46 / 1976 and spiegel-online.de archive: Part I ; Part II ; Part III . Retrieved April 5, 2011.

- Thomas Scheuer: The last secret of the hero of Mogadishu . In: Focus , 27/2016 of July 11, 2016.

- Hans Riebsamen: Look at Operation Entebbe: In a bad German tradition. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung of September 30, 2016.

- Susanne Bressan: Entebbe's selection? Who invented it? For the exhibition at the Anne Frank educational center (Frankfurt am Main). In: haGalil , November 30, 2016.

- Roland Kaufhold : 40 years after Entebbe: German Left, memories of the Holocaust and anti-Zionism. In: haGalil , February 2, 2017.

- Susanne Benöhr-Laqueur, Yael Pulë: New interpretation - reinterpretation - misinterpretation. In: haGalil, February 7, 2017.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d Ulrich Beyerlin: Treatises: The Israeli liberation action of Entebbe in terms of international law. (PDF file; 2.3 MB) at: zaoerv.de Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law, 1977.

- ↑ Entrevista: La aventura del secuestro de Entebbe, contada por una protagonista, in: El País of July 11, 1976, accessed on August 12, 2014 (Spanish)

- ^ Claude Moufflet: Otages a Kampala. P. 151.

- ↑ Roland Kaufhold (2017): 40 years after Entebbe. German Left, Memories of the Holocaust and Anti-Zionism. In: haGalil: http://www.hagalil.com/2017/02/40-jahre-nach-entebbe/ .

- ↑ Entebbe thirty years on: Mancunian on board. In: Jewish Telegraph Online from 2006, accessed on August 11, 2014.

- ↑ Markus Eikel: No "breathing space" . In: Quarterly Books for Contemporary History . tape 2/2013 . Oldenburg Wissenschaftsverlag GmbH, 2013, ISSN 0042-5702 , p. 239 ff .

- ↑ Hijacking of Air France Airbus… (PDF, 10 pages), p. 1, in: Keesing's Record of World Events. 1976 (English)

- ↑ comprehensive report in the archive of the IDF, p. 9, paragraph 1 ( Memento of December 14, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF file; 5.5 MB)

- ^ Robin Bidwell: Dictionary Of Modern Arab History. Routledge, London / New York 2010, p. 167 (English).

- ^ John W. Amos: Palestinian Resistance: Organization of a Nationalist Movement. Elsevier, Amsterdam 1980, p. 232 (English).

- ^ Jean-Pierre Filiu: Gaza: A History. Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 2014, p. 396 (English).

- ↑ PFLP communiqué of July 6, 1976, distributed by Radio Uganda, documented in: Collection of materials on Markus Mohr (Ed.): Legenden um Entebbe. (PDF) On the Unrast-Verlag website, May 2016, accessed on January 19, 2017.

- ↑ Yehuda Ofer: Operation Thunder: The Entebbe Raid. P. 6.

- ↑ Passengers Comment on Air France Hijacking (PDF), a note from the US Embassy in Tel Aviv dated July 8, 1976, accessed from The National Archives on August 12, 2014.

- ↑ a b c Raffi Berg: Recollections of Entebbe, 30 years on. In: BBC News of July 3, 2006, accessed July 17, 2014.

- ↑ Saul David: Operation Thunderbolt. P. 72.

- ^ Helen Epstein: Idi Amin's Israeli Connection. In: New Yorker, June 27, 2016, accessed January 20, 2017.

- ↑ Idi Amin and Israel: First Love, Then Hate. In: Jewish Telegraphic Agency, August 20, 2003, accessed January 20, 2017.

- ↑ Gerald Utting: The Israeli raid: 'I forgive everybody'. In: The Montreal Gazette, July 16, 1977, accessed July 19, 2014.

- ↑ a b Quarante ans après la prize d'otages d'Entebbe, les revelations des archives diplomatiques. In: Le Monde of December 28, 2016 (French).

- ↑ Saul David: Operation Thunderbolt. P. 61.

-

^ Gerhard Hanloser : Federal Republican Left Radicalism and Israel - Antifascism and Revolutionism as Tragedy and Farce. In: Moshe Zuckermann (Ed.): Antisemitism, Antizionism, Israel criticism. Wallstein, Göttingen 2005, ISBN 3-89244-872-8 , p. 194.

Matthias Brosch (Hrsg.): Exclusive solidarity. Left anti-Semitism in Germany. From idealism to the anti-globalization movement. Metropol, Berlin 2007, ISBN 3-938690-28-3 , p. 343ff.

Timo Stein: Between anti-Semitism and criticism of Israel. Anti-Zionism in the German left. VS-Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2011, ISBN 978-3-531-18313-8 , p. 52. - ↑ Annette Vowinckel: Skyjacking: The airplane as a weapon and icon of terrorism. In: Klaus Biesenbach: To the concept of terror. The RAF exhibition. Steidl, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-86521-102-X , Volume 2, p. 151.

-

↑ Susanne Benöhr-Laqueur, Yael Pulë: New interpretation - reinterpretation - misinterpretation. In: haGalil of February 7, 2017.

Edgar H. Brenner, Alexander Yonah: Legal Aspects of Terrorism in the United States. Volume 3. Oceana Pub., New York 2000, ISBN 0-379-21430-X , p. 371. -

↑ Andreas Musolff: The terrorism discussion in Germany from the end of the sixties to the beginning of the nineties. In: Georg Stötzel , Martin Wengeler (ed.): Controversial terms. History of public language use in the Federal Republic of Germany. (= Language, Politics, Public , Volume 4.) de Gruyter, Berlin 1995, ISBN 3-11-014652-5 , p. 423f.

Annette Vowinckel : Airplane hijackings. A cultural story. Wallstein, Göttingen 2011, ISBN 978-3-8353-0873-2 , p. 107. - ↑ David Tinnin: Like Father. In: Time . August 8, 1977; Julian Becker: A review of Hitler's children. Page 2

- ↑ Laly Derai: Je dois ma vie à Tsahal. ( Memento of December 30, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) In: Hamodia of June 11, 2011, accessed on July 21, 2014 (French).

- ↑ Jeremy Josephs: Michel Bacos: the Air France hero of Entebbe. In: Jewish Chronicle, June 15, 2012, accessed July 21, 2014.

- ↑ Entebbe postscript. In: Flight International, July 17, 1976, accessed July 19, 2014.

- ↑ Israel marks 30th anniversary of Entebbe, in: USA Today of July 4, 2006, accessed on July 21, 2014 (English)

- ↑ The Rescue: 'We Do the Impossible'. , Time Magazine. Monday July 12, 1976. Retrieved July 26, 2009.

- ^ Institute for Contemporary History (Ed.): Files on the Foreign Policy of the Federal Republic of Germany. Oldenbourg, Munich 2007, p. 1020.

- ↑ a b 1976: Israelis rescue Entebbe hostages , BBC - On this day. July 4, 2008. Retrieved July 26, 2009.

- ↑ Tamara Zieve: This Week in History: Operation Thunderbolt, in: Jerusalem Post, June 24, 2012, accessed July 19, 2014

- ↑ France: Air France airbus hijacked by Palestinian guerrillas returns from Uganda. Report from the ITN news agency dated July 23, 1976, accessed on August 22, 2016

- ↑ Jonathan Kandell: Kurt Waldheim, Former UN Chief, Is Dead at 88. In: New York Times, June 15, 2007, accessed July 21, 2014.

- ↑ Chaim Herzog: Heroes of Israel: Profiles of Jewish Courage. Little Brown, September 1989.

- ↑ Chaim Herzog: Heroes of Israel. P. 284.

- ↑ Hillel Fendel: Israel Commemorates 30th Anniversary of Entebbe Rescue. In: Israel National News . July 5, 2006.

- ↑ Annette Vowinckel: The short way to Entebbe or the extension of German history in the Middle East. In: Zeithistorische Forschungen / Studies in Contemporary History. Online edition, 1 (2004), no.2, (online)

- ↑ Ilse Dorothee Pautsch, Matthias Peter, Michael Ploetz, Tim Geiger: Files on the Foreign Policy of the Federal Republic of Germany 1976. Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 2007, ISBN 978-3-486-58040-2 .

- ↑ Hans Schueler: Terror without end. The Entebbe campaign was a godsend . In: The time. July 9, 1976, p. 1. Quoted from: Annette Vowinckel The short way to Entebbe ... 2004, p. 11.

- ↑ hardship means massacre . In: Der Spiegel . No. 28 , 1976, p. 21-25 ( online ).

- ↑ Airplane hijacking : Terrorists freed. In: The time. 3rd November 1972.

- ^ Markus Mohr: Instantbooks . In: Derselbe (Ed.): Legends about Entebbe. An act of air piracy and its dimensions in the political discussion . Unrast Verlag , 2006, pp. 105–129, here: pp. 106–111.

- ↑ Markus Mohr: Campaign against a "propaganda film" and the Entebbe criminal trial . In: Derselbe (Hg): Legends about Entebbe. An act of air piracy and its dimensions in the political discussion . Unrast Verlag , 2016, pp. 151–173, here: pp. 152–154.

- ↑ a b Judith E. Doneson: The Holocaust in American movie, Judaic traditions in literature, music, and art. 2nd edition. Syracuse University Press, 2002, ISBN 0-8156-2926-5 .

- ↑ Manuel Borutta, Frank Bösch (ed.): Moving the masses: Media and emotions in the modern age. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt a. M. 2006, ISBN 3-593-38200-8 .

- ↑ Thomas Ammann: From Auschwitz to Entebbe. In: arte. June 30, 2010.

- ↑ Thomas Gehringer: “From Auschwitz to Entebbe”: And again a German selects. (Review) In: tagesspiegel.de , June 28, 2010. Accessed April 4, 2011.

- ^ Operation Donnerschlag - Israel against German terrorists. ARD , accessed on June 1, 2016 .

- ↑ Entebbe Memorial for Yoni Netanyahu, in: Arutz Sheva of July 7, 2005, accessed on July 19, 2014 (English)

- ↑ Eetta Prince-Gibson: Entebbe's Forgotten Dead. In: Tablet of March 7, 2013, accessed on July 18, 2014 (English).

- ↑ Caroline Glick: Our World: From Yoni to Gilad, in: Jerusalem Post of July 4, 2006, accessed on July 22, 2014 (English)

- ↑ Sharon Roffe-Ofir: Entebbe's open wound. on: Ynet. 7 February 2006.

- ↑ Josh Hamerman: Battling against 'the falsification of history'. on: Ynet News. February 4, 2007.

- ↑ Uri Dromi: Still fighting over Entebbe, in: Haaretz of November 2, 2006, accessed on July 21, 2014 (English)

- ↑ Hans-Joachim Klein: Return to Humanity. Appeal from a terrorist who has dropped out. Reinbek 1979, p. 210

- ↑ Revolutionary cell: Gerd Albartus is dead. In: ID archive in the IISG / Amsterdam (ed.): Frucht des Zorns. Texts and materials on the history of the Revolutionary Cells and the Red Zora. Edition ID-Archiv, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-89408-023-X , pp. 20–34. There dated December 1991, Gerd Albartus is dead.

- ↑ Gunther Latsch: History of Terror: Eldorado of the left-wing guerrilla. In: Spiegel Special , June 29, 2004. p. 89.

- ^ Matthias Brosch (ed.): Exclusive solidarity. Left anti-Semitism in Germany. From idealism to the anti-globalization movement. Metropol, 2007, ISBN 3-938690-28-3 , p. 343.

- ^ Henryk M. Broder: The final solution of the Israel question . Welt Online , March 6, 2012, accessed July 22, 2014

- ↑ This path had to be ended . In: Der Spiegel from January 8, 2001, accessed on July 22, 2014

- ^ Gerhard Hanloser: Left radicalism and Israel. Antifascism and revolutionism as a tragedy and a farce. In: Moshe Zuckermann (Ed.): Antisemitism - Antizionism - Israel criticism. Tel Aviv yearbook for German history. Wallstein Verlag, 2005, ISBN 3-89244-872-8 , pp. 181-213, here: p. 194.

- ^ Rudolf van Hüllen : "Anti-imperialist" and "anti-German" currents in German left-wing extremism. Federal Agency for Civic Education , January 5, 2015, accessed on July 11, 2016.

- ^ About the conference: Matthias Brosch: Anti-Semitism in the German Left. Meeting of the Hans Böckler Foundation from November 26, 2004 to November 28, 2004 in the IG Metall educational facility in Berlin / Pichelssee, October 4, 2004, accessed on July 11, 2016.

- ↑ Age of Terror (1/4 to 4/4), message in the Phoenix press portal about the broadcast on April 12, 2012, accessed on August 12, 2014.

- ^ Operation Thunderbolt - Israel's Fight Against Terrorism, on the website of the production company Prounen Film, accessed on July 23, 2014.

- ↑ Tony Shaw: Cinematic Terror: A Global History of Terrorism on Film, Bloomsbury, London / New York 2015, p. 137.