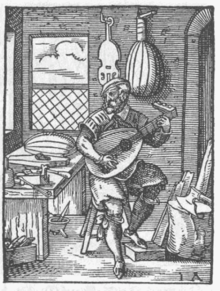

Renaissance lute

Renaissance lute refers to a hunchback lute in fourth / third tuning , as it was first used in Europe from around 1500 to 1620 (i.e. the time of the Renaissance ).

history

Preforms of the European lute may have come to Europe through crusaders . Perhaps it found its way to Central Europe earlier via Moorish Spain or on the way through the Byzantine Empire bordering Persia . In Europe, the sounds received generally frets of gut strings. What was decisive, however, was the transition from playing the pick to finger touch ( Arnold Schlick and Hans Judenkönig ) at the beginning of the 16th century. This begins the polyphonic solo playing typical of the Renaissance . Separate fingering ( tablatures , lute tablatures ) have also been developed for the lute .

The first written tradition of the music can be found shortly after 1500 with the Italian lutenist Francesco Spinacino . In addition to tablatures of vocal music and instrumental dance music, there are already independent, instrumentally composed solo pieces ( ricercar ). The emancipation of instrumental music leads to the creation of free forms such as toccata , fantasy and prelude for the lute . Giulio Cesare Barbetta (1540–1603) is considered the first composer to write and publish sheet music for the seven-course lute. The centers of lute playing at this time were Venice , Rome , France and southern Germany. The court chapel of Elector Maximilian I in Munich with the lutenist Michelangelo Galilei should be mentioned here as well as the French royal court.

The Elizabethan lute song then flourished in England around 1600 . John Johnson (1540–1594), Anthony Holborne (1545–1602) and Daniel Bacheler (1572–1619), finally John Dowland (1563–1626) and his son Robert (1591–1641) are among the most important lutenists of their time. About 100 solo compositions for 6- to 9-course lute by John Dowland alone have been preserved. They are among the most demanding and mature works for this instrument and are now part of the repertoire of almost all lutenists and classical guitarists.

The flower of the French Air de court in which the sounds initially the independent instrumental accompaniment of song takes ( Gabriel Bataille , Nicholas Lanier ) describes the transition to the baroque lute and other sound instruments like Mandora , theorbo and Angélique , to the sounds eventually from other stringed and keyboard instruments .

Only with the rediscovery of early music during the 20th century did the lute experience a revival in its various forms.

Lute technology

Mood

The renaissance lute is usually in a third-fourth tuning, similar to the guitar, but (with six choirs) with the third interval between the third and fourth choir. The absolute pitch was not initially fixed. In contemporary textbooks it is often recommended to simply tune the highest choir as high as possible. With a length of about 59 cm, the following typical moods result (for the alto lute) with the usual intestinal sides :

- 6-course tuning: Gg cc 'ff' aa d'd 'g' (in German-speaking countries also Aa dd 'gg hh e'e' a ')

- 7-course tuning: Ff Gg Cc ff aa d'd 'g'

- 8-course tuning: Dd Ff Gg Cc ff aa d'd 'g'

In addition to the “right chorus or alto lute”, Michael Praetorius also used the “small octave loud”, the “small discant loud”, the “discant loud”, the “tenor loud”, the “bass” and the “large octave bass ” by Michael Praetorius in 1618 According to “described. The pitch of the highest string accordingly encompassed a spectrum from g to d ''.

construction

The renaissance lute has a teardrop-shaped sound body ("shell") composed of many wood chips. Yew wood was often used . The top is mostly made of spruce wood and is divided by several beams inside the lute. The neck is glued to the shell and the wooden block under the ceiling in such a way that the fingerboard and the ceiling are on the same level. A rosette ( sound hole ) is carved into the ceiling . The tailpiece is glued on between the rosette and the lower edge of the ceiling ("bridge", "latch"). The pegbox is glued to the upper end of the neck and is bent backwards. The renaissance lute usually had 6 or (from around the end of the 16th century) 7 choirs. Instruments with 8 or more choirs were soon created . In otherwise double-stringed choirs, the highest string is often simply designed as a chanterelle .

Thus the classical (Renaissance) lute is described in the Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung 1831: "The lower strings, mostly starting from the third, are doubled, partly in unison, partly in octave. Such a reference is called a choir; Name, which is also used without distinction when counting the chords for the simple chords. One therefore says, for example: the lute has eleven choirs, whereby the uppermost (chanterelle) and the likewise simple two following are included. " .

Centers of lute making during the Renaissance

Füssen is considered to be the cradle of commercially operated lute making in Europe. In 1562 the Füssen lute makers joined together to form the first lute maker guild in Europe. At times, up to 20 master lute makers worked in Füssen, which at that time had around 2000 inhabitants. Hundreds of Füssen lute and violin makers emigrated to establish workshops in the European cultural metropolises, at royal courts and in large trading cities and to practice their craft successfully. In the 16th and 17th centuries around two thirds of all lute makers in Venice and Padua were of Füssen origin. Lute and violin making was also dominated by the Allgäu in Rome and Naples . But the emigrated masters often kept in touch with their homeland. Some of them continued to get their wood from the Füssen region, and journeymen or apprentices followed them from home.

Among the earliest known lute makers are Laux Maler (1518–1552, Bologna) and Hans Frei (1450–1523, Bologna and Nuremberg). An indication of the successful integration of the lute makers from Germany in their new homeland is the adaptation of the German proper names: Matthäus and Georg Seelos became Matteo and Giorgio Sellas, Magnus Lang called himself Magno Longo, Michielle Harton is easy to recognize as Michael Hartung . In particular, the name of the famous Füssen lute maker family Tieffenbrucker (examples are Caspar , Magnus and Wendelin Tieffenbrucker ), which is difficult to pronounce , has been corrupted accordingly: "Duiffoprugcar", "Dubrocard", "Dieffobruchar". Important lute makers working in Germany were also Heinrich Helt and Conrad Gerle from Nuremberg and Hans Meisinger from Augsburg .

Only a few original renaissance lutes have survived. Many renaissance lutes, in particular the Bolognese master Laux Maler and Hans Frei , were bought up in the 17th century, brought to France and converted into baroque lutes here .

Important composers and instrumentalists of the Renaissance lute (selection)

- Joan Ambrosia Dalza (active around 1508), Italy

- Vincenzo Capirola (1474– after 1548), Italy

- Pierre Attaingnant (1494–1552), editor, France

- Francesco da Milano (1497–1543), Italy

- Valentin Bakfark (1507–1576), Hungary

- Hans Neusidler (around 1508–1563), Germany

- Adrian Le Roy (around 1520-1598), France

- Melchior Neusidler (around 1531–1591), Germany

- John Johnson (around 1540-1594), England

- Francis Cutting (about 1550-1595), England

- Wojciech Długoraj (around 1550–1620), Poland

- Thomas Robinson (about 1560-1610), England

- Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck (1562–1621), Netherlands

- John Dowland (1563-1626), England

- Jean-Baptiste Besard (around 1567–1625), France

- Nicolas Vallet (1583–1642), Netherlands

- Jane Pickering , editor ( Lute Book , 1616–1645) and composer

literature

- Konrad Ragossnig : Manual of the guitar and lute Schott ISBN 978-3-7957-8725-7 .

- Konrad Ragossnig: Renaissance music based on lute tablatures. Edition Schott, Mainz (= guitar archive. Volume 442).

- Andreas Schlegel: The lute in Europe - history and stories to enjoy. (German, English) Lute Corner ISBN 978-3-9523232-0-5 .

- Andreas Schlegel, Joachim Lüdtke: Die Lute in Europa 2 / The Lute in Europe 2- Lutes, Guitars, Mandolins and Cisters / Lutes, Guitars, Mandolins, and Citterns (German, English) Lute Corner ISBN 978-3-9523232-1- 2 .

- Douglas Alton Smith: A History of the Lute from Antiquity to the Renaissance . Lute Society of America , 2002. ISBN 0-9714071-0-X , ISBN 978-0-9714071-0-7 .

- Matthew Spring: The Lute in Britain. A History of the Instrument and its Music. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2006. ISBN 0-19-518838-1 - Chapter 6. The Lute in Consort. (PDF file; 1.79 MB).

- Stefan Lundgren: School for the Renaissance Lute. Reyermann and Lundgren, Munich 1981.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Francesco Spinacino: Intabulatura de Lauto , Venice 1507

- ^ Cornelia Oelwein: Galileo Galileis Munich relatives. The instrumentist Michelangelo Galilei. Bayerischer Rundfunk, Munich 2006

- ^ Adalbert Quadt : Lute music from the Renaissance. According to tablature ed. by Adalbert Quadt. Volume 1 ff. Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1967 ff .; 4th edition, ibid. 1968, Volume 2, Introduction.

- ^ Konrad Ragossnig : Handbook of the guitar and lute. Schott, Mainz 1978, ISBN 3-7957-2329-9 , p. 12 f. and 15.

- ^ Adalbert Quadt: Lute music from the Renaissance. According to tablature ed. by Adalbert Quadt. Volume 1 ff. Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1967 ff .; 4th edition, ibid. 1968, Volume 2, Introduction.

- ↑ The lute tablature . Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung, No. 9, March 2, 1831, p. 134

- ↑ Richard Bletschacher : The lute and violin makers of the Füssen country. Hofheim am Taunus, 1978, 1991². ISBN 3-873-50-0043 .

- ↑ Jane Pickering's Lute Book .