Therese Neumann

Therese Neumann , called Resl von Konnersreuth (born April 8, 1898 in Konnersreuth ; † September 18, 1962 ), was a farmer's maid who became very well known as a Catholic mystic because of her alleged stigmata and the alleged lack of food for years and who triggered real pilgrimages. It was not until long after her death that Bishop Gerhard Ludwig Müller opened a beatification process in 2005 that a certain ecclesiastical recognition took place.

Life

Therese Neumann was born as the first of eleven children of the master tailor Ferdinand Neumann and his wife Anna Neumann née Grillmeier and was baptized in their place of birth Konnersreuth. The details of the birthday in the parish registers are inconsistent, the birth entry in the Konnersreuth registry office is not known. The family is possibly related to the famous Eger master builder Balthasar Neumann (1687–1753). One sister was the housekeeper of Eichstätter Bishop Joseph Schröffer ; another, Ottilie, housekeeper of the Konnersreuth local chaplain Joseph Naber. Resl's thirteen years younger brother Ferdinand Neumann (called Ferdl) was a local politician , district administrator in Kemnath from 1949 to 1957 and sat for the CSU in the Bavarian state parliament from 1946 to 1950 . Little is known about the other siblings and their descendants. One of the siblings died before 1955.

From 1912 the girl worked as a maid on the neighboring farm belonging to a relative and from 1915 onwards, during the war-related absence of the farm owner, she ran the farm in a responsible position as a grandmaid. After extinguishing a barn fire in March 1918, Therese began to be ailing. Vegetative complaints set in, which led to physical breakdowns and various falls. In September 1918 visual disturbances began to occur, which increased to complete blindness by March 1919 and were temporarily accompanied by deafness and epilepsy-like seizures. Since October 1918 she suffered from paralysis, which led to bed rest and incapacity for work. Therese Neumann had to be looked after for years. As of December 1922, swallowing problems also occurred. Only in 1923, on the day Therese von Lisieux was beatified , could she suddenly see again; In 1925, on the day of the canonization of her namesake, the paralysis also disappeared, according to information from her surroundings, which flowed into her later life.

From February 1926, Therese Neumann showed stigmata and bleeding from her eyes, which led to a large number of visitors. Sometimes up to 5,000 visitors were counted on Good Fridays , on which the stigmatization was particularly evident.

Since 1926 she is said to have neither eaten nor drunk apart from communion . Since then she is also said to have regularly experienced visions of predominantly biblical scenes in the New Testament .

Paramahansa Yogananda visited the “great Catholic mystic, Therese Neumann von Konnersreuth” on July 16, 1935. He describes the visit in his book Autobiography of a Yogi .

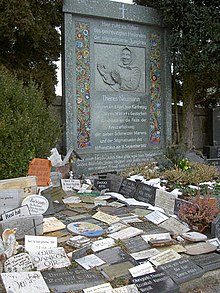

Therese Neumann died of a heart attack in 1962 and was buried in a crypt in the Konnersreuth cemetery. Today her grave is the destination of pilgrims and tourists from all over the world. Before her death, through her initiative and a financial contribution from her donated money, the Fockenfeld Castle and Gut was bought and the Fockenfeld Monastery was founded in the property near Konnersreuth and Mitterteich . After her death, the Theresianum Monastery was built near Therese Neumann's crypt, financed by donations . Since 2010, the information and meeting center e. V. in Konnersreuth.

Stigmata

The appearance of the stigmata began in Lent before Easter 1926 with a vision in which, according to her statements, she saw Jesus sweating blood on the Mount of Olives, when a 3 cm long and 1 cm wide wound appeared in the area of the heart. Later there were wounds on the hands, feet and head, as well as smaller wounds spread over the body, which were interpreted as traces of the flagellation . On Good Friday there was also a shoulder wound, which was explained by the carrying of the cross. The wounds on the back of the hand and foot were initially round with a diameter of 12–13 mm and later became square. They were smaller on the palms of the hands and on the soles of the feet. On the head she was bleeding in nine places in a wreath. The wounds on her heart, hands, and feet usually bled every Friday during her visions of the Passion of Christ. On Good Fridays, the scourge wounds and head wounds were also bleeding, and tears of blood flowed from her eyes. Therese Neumann wore the stigma until the end of her life.

controversy

Therese Neumann polarizes. There were and are passionate advocates, especially the eyewitnesses from the Konnersreuth district such as Pastor Joseph Naber, the Eichstätter priest and paleontologist Franz Xaver Mayr , the historian Fritz Gerlich , and opponents such as the Catholic priest Josef Hanauer , the doctor Josef Deutsch or the Historian and publicist Hilda Graef , who had a short conversation with her in Konnersreuth in the presence of the local pastor Joseph Naber. At Therese Neumann's request, visitors were repeatedly unloaded; in particular, critics and even merely potential doubters - with few exceptions - were never received by her. Both sides wrote books and writings on Konnersreuth, for example the eyewitness Johannes Steiner , who described everything that happened around Therese Neumann and her mystical experiences, and Hanauer, who discovered numerous contradictions, inconsistencies and unusual facts in the life of Therese Neumann and vehemently against which, in his words, "pseudomysticism" and "miracle addiction" fought.

As early as July 1927, the Regensburg Episcopal Ordinariate carried out an official 14-day investigation on site, which was continued in March 1928. The management was incumbent on the physician Otto Seidl from nearby Waldsassen , who had been taking care of Neumann for a long time and who carried out the examinations of the physical phenomena together with the psychiatrist and eugenicist Gottfried Ewald , then senior physician at the clinic of the University of Erlangen and later professor in Göttingen. The Regensburg priest and anthropologist Sebastian Killermann was also present for two days and in March 1928 wrote a report on his observations at Neumann. Killermann closes his report "with great doubt", since he was never able to personally observe the start of the bleeding. After he was referred to the room to ventilate, the previously dried blood under Therese Neumann's eyes was fluid again after his return. “The blood on the cheeks”, Killermann continues, “was not actually fresh (arterial)”, but seemed “to have been made liquid by being softened (perhaps with saliva)”. Ewald, on the other hand, expressly speaks in his investigation report of the spontaneous onset of the bleeding. This had been "observed perfectly by several doctors, some with a magnifying glass". An artificial induction is excluded. He explains the origin of the stigmata psychologically as a " psychogenic , i. H. conditioned by experiences ”. Gerlich also describes the stigmata and the processes around the beginning of the bleeding in the ecstasies in detail and with sketches. Since there were still doubts about the authenticity of the stigmas or about Neumann's lack of food, the Bavarian bishops demanded Neumann's stay in a Catholic hospital in 1932 in order to make a detailed examination of all processes possible. However, the Neumann family declined this and further investigations.

On the part of the Catholic Church, which advised against pilgrimages to Konnersreuth as early as 1927 - the year the official investigation was carried out - neither the stigmatization nor the lack of food were officially recognized. Later, too, the church authorities were generally more likely to respond to the demands that their followers made after the death of the seer for church recognition of the supernatural phenomena surrounding Therese Neumann (and despite different assessments by the competent Regensburg bishops Michael Buchberger , Rudolf Graber and Manfred Müller ) hesitant.

The retired evangelical pastor and Aramaist Günther Schwarz dealt in his book Daszeichen von Konnersreuth , published in 1994 by the diocese of Regensburg , from a biblical perspective with the visionary's visions of the passion and resurrection of Jesus Christ and especially with the phenomenon that she allegedly heard quotations was able to reproduce in an Aramaic dialect understandable for experts. In a lecture on his investigations in the same year, the researcher spoke of "details that are indescribable, that they could never have read or thought up." His assessments were based primarily on transcripts made by family members of tape recordings on which Therese Neumann reported of their visions. As Josef Hanauer reported, the sharpest critic of Neumann's private revelations , who considers the language phenomenon to be the result of suggestive interviews by Eichstätter classical philologists and the local priest, was emphasized in 1994 at the annual meeting of the "Konnersreuther Ring" (where Schwarz had spoken), a beatification of Neumann is only conceivable “if Hanauer is refuted word for word” - and this could “only be done according to the method of Dr. Günther Schwarz happened. ”In 1997, Hanauer interpreted this as an admission that beatification was never possible, and described the supporters' campaign for beatification as“ dumbing down the people ”because it was known that the church authorities in Rome had been involved in such a procedure at the latest 1982 would be clearly negative.

Despite the skeptical attitude of the episcopal ordinariate, “Resl” continued to be venerated in popular piety . A request for her beatification was supported by 40,000 signatures. The Regensburg Bishop Gerhard Ludwig Müller then opened a process of beatification for Therese Neumann in 2005, after he had obtained the necessary nihil obstat (the declaration of no objection) from the Roman Congregation for the beatification and canonization processes . The costs for the elaborate procedure (a first invoice from the Vatican from 2006 amounted to 26,000 euros) are covered by a specially created donation fund. The costs are mainly incurred for translation work into Italian and for travel expenses for the more than 60 witnesses who are to be heard in the course of the proceedings.

The forensic biologist Mark Benecke had previously published an article in the Süddeutsche Zeitung in early 2004 in which he reported that the DNS working group of the Munich Institute for Forensic Medicine had meanwhile examined blood from Therese Neumann's associations and their results at a conference of the German Society for Forensic medicine presented in Cologne. The blood most certainly came from herself and not from animals. Of course, it cannot be ruled out that Therese Neumann may have inflicted the wounds on herself. The DNA examination cannot be regarded as proof of the “authenticity” of the stigmatization.

A further evaluation of the studies on Neumann's symptoms at the Psychiatric Clinic of the Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich comes to the conclusion that the physical disorders (temporary paralysis and blindness), the stigmas and the ecstasies in the context of psychosomatic symptom formation as reaction options under the The influence of religious fantasies can be explained. On the other hand, there are considerable doubts about the lack of food in view of the urine results (initially typical "hunger urine", later no more) and the corresponding weight profile with initial decrease and later increase, so that at the end of the observation period the initial weight was reached again. Hanauer also describes observations and incidents in his books that suggest that Therese Neumann constantly consumed food, including observations by her niece.

literature

- Erwein von Aretin : Theresia Neumann. Munich 1952.

- Bernhard M. Baron : When Emmy Ball-Hennings visited the 'Konnersreuther Resl' in 1927 in: Heimat-Landkreis Tirschenreuth , Vol. 28, 2016, ISBN 978-3-939247-70-8 , pp. 167-175.

- Erika Becker: loved - wanted - found. Therese Neumann accompanies seekers of truth. Naumann, Würzburg 1996, ISBN 3-88567-068-2 .

- Wolfgang Johannes Bekh : Therese von Konnersreuth or the challenge of Satan. Ludwig, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-7787-3473-3 .

- Josef Deutsch: To Konnersreuth. Medical criticism of Dr. Fritz Gerlich's book: Die Stigmatierte von Konnersreuth , Lippstadt 1932.

- Helmut Fahsel: Konnersreuth. Facts and thoughts. Second edition. Basel 1949.

- Christian Feldmann : madness or miracle? The Resl von Konnersreuth as she really was. Regensburg 2010.

- Fritz Gerlich : The stigmatized Therese von Konnersreuth. Volume 1: The life story of Therese von Konnersreuth. Volume 2: The credibility of Therese von Konnersreuth. Munich 1929.

- Fritz Gerlich: The struggle for the credibility of Therese Neumann. Munich 1931.

- Hilda Graef : Konnersreuth. The Therese Neumann case. Einsiedeln 1953.

- Hans Grüter: Le mystère de Theresia de Konnersreuth. Locarno 1947.

- Josef Hanauer : Konnersreuth as a test case. Critical report on the life of Therese Neumann. Manz, Munich 1972, ISBN 3-7863-0139-5 .

- Josef Hanauer: The Konnersreuth hoax - a scandal without end. Self-published, 1989.

- Josef Hanauer: Konnersreuth. Or: a case of dumbing down the people. Karin Fischer publishing house, Aachen 1997, ISBN 3-89514-107-0 .

- Michael Hesemann : Stigmata. They bear the wounds of Christ. Güllesheim 2006.

- Alfred Hoche : The miracles of Therese Neumann von Konnersreuth. JF Lehmann, Freiburg i. B., Munich 1933.

- Franz X. Huber: The Mystery of Konnersreuth. Karlsruhe 1949.

- Sebastian Killermann : Report on my observation to Therese Neumann in Konnersreuth 22/23. III. 1928 , Regensburg 1928.

- Christiane Köppl: Neumann, Therese von Konnersreuth. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 19, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-428-00200-8 , p. 162 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Joseph Naber : Diaries and notes about Theres Neumann on the 25th anniversary of the death of the stigmatized , ed. by Johannes Steiner. Schnell and Steiner, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-7954-0155-0 .

- Albert Panzer : Light from over there. A journalist accompanies Therese Neumann's mystical life. Verlag "Der neue Tag", Amberg 1992.

- Paul Rieder : The stigmatized from Konnersreuth: Therese Neumann before the beatification. Mediatrix-Verlag, Vienna 1979, ISBN 3-85406-015-7 .

- Luise Rinser : The truth about Konnersreuth. A report. Frankfurt am Main and Hamburg 1954.

- Max Rößler : Therese Neumann von Konnersreuth. Naumann, Würzburg 1989, ISBN 3-88567-056-9 .

- Sabine Scholz, Josef Wolfgang Degen: "Bad boy, I pray that you will go to hell." Memories of school days in the monastery. Turin 2008.

- Günther Schwarz : The sign of Konnersreuth. Edited by the department for beatification and canonization processes at the Episcopal Consistory for the Diocese of Regensburg, Regensburg 1994.

- Günther Schwarz: Visions of Therese Neumann from Konnersreuth. Hochschulverlag (Günter Mainz Publishing Group), Aachen 2012, ISBN 978-3-8107-0107-7 .

- Joachim Seeger: Resl von Konnersreuth (1898-1962). A scientific study of the career, effect and veneration of a popular saint. Frankfurt am Main et al. 2004, ISBN 3-631-52495-1 .

- Otmar Seidl On the stigmatization and lack of food of Therese Neumann (1898–1962) , in Der Nervenarzt , specialist journal for the fields of psychiatry and neurology , Volume 79 (7), Springer Wissenschafts-Verlag , 2008, pp. 836–844.

- Johannes Steiner : Theres Neumann von Konnersreuth, a picture of life. Schnell and Steiner, Munich 1963, 10th edition 1988, ISBN 3-7954-0155-0 .

- Johannes Steiner: Visions of Therese Neumann. Special edition Schnell and Steiner, Regensburg 2007, ISBN 978-3-7954-1986-8 .

- Ulrich Veh : The Resl: Therese Neumann von Konnersreuth. Eichstatt 1988.

- Konrad Fuchs : Neumann von Konnersreuth, Therese (1898-1962). In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 14, Bautz, Herzberg 1998, ISBN 3-88309-073-5 , Sp. 1307-11313.

Web links

- Literature by and about Therese Neumann in the catalog of the German National Library

- Newspaper article about Therese Neumann in the press kit of the 20th century of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Therese Neumann von Konnersreuth , website of the Konnersreuther Ring eV

- Multilingual site about Therese von Konnersreuth

- Literature on Therese Neumann

- Konnersreuth's swindle and other books by Josef Hanauer online

- Various files and correspondence on Therese Neumann von Konnersreuth can be found in the estate of the theologian Johann Baptist Westermayr in the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Death picture: Death picture. In: https://www.wgff-tz.de/kontakt.php . Death note collection, accessed June 25, 2019 .

- ^ Opening of Therese Neumann's beatification process . Report on the website of the Diocese of Regensburg from February 14, 2005 (accessed on June 8, 2016).

- ^ Notes on this from Karl Siegl : Balthasar Neumann. In: Our Egerland - magazine for homeland exploration and homeland care , year 1932, pages 74 to 89.

- ↑ Who is guilty? In: Der Spiegel , No. 16/1955, p. 20.

- ^ A b Otmar Seidl : On the stigmatization and lack of food of Therese Neumann (1898–1962). In: Der Nervenarzt , specialist journal for the fields of psychiatry and neurology. Volume 79, Issue 7, 2008, Springer Wissenschaftsverlag, pp. 836-844.

- ↑ Short biography on the website of the "Konnersreuther Ring".

- ^ A b Paramahansa Yogananda: Therese Neumann, the Catholic Stigmatist of Bavaria . In: Autobiography of a Yogi. Cape. 39, Oxford (Mississippi) 1946.

- ↑ Paramahansa Yogananda: Jesus' Temptation in the Desert In: The Second Coming of Christ Discourse: 8, page: 200–201, Self-Realization Fellowship, 2013.

- ^ Anni Spiegl: Life and death of Therese Neumann von Konnersreuth . Self-published, Konnersreuth 1976

- ^ A b Fritz Gerlich: The Stigmatized von Konnersreuth - Volume 1: The life story of Therese Neumann . Verlag J. Kösel & F. Pustet, Munich 1929 (PDF; 830 kB)

- ^ Josef Hanauer: Konnersreuth as a test case. Critical report on the life of Therese Neumann . Manz, Munich 1972.

- ^ Archives of the Bishop. Ordinariates Regensburg, inventory Therese Neumann, Fasz. No. 102

- ^ Fritz Gerlich: The stigmatized Therese von Konnersreuth. First part. Munich 1929, p. 27 and Note 1.

- ^ Astrid Ley: Forced sterilization and the medical profession: Background and goals of medical action 1934-1945. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt / New York 2004, p. 263 u. Note 58.

- ↑ Sebastian Killermann: Report on my observation to Therese Neumann in Konnersreuth 22/23. III. 1928 , Regensburg 1928, p. 8.

- ^ Gottfried Ewald : The stigmatized von Konnersreuth - investigation report and expert opinion. JF Lehmanns Verlag, Munich 1927, p. 35.

- ↑ Christian Feldmann: Delusion or Miracle? The Resl von Konnersreuth as she really was. Regensburg 2010, p. 37.

- ↑ a b c Cf. Irmgard Oepen: Book review: Konnersreuth. A case of dumbing down the people? In: Skeptiker (Journal of the Society for the Scientific Investigation of Para sciences ) 3/1999, pp. 130-131.

- ↑ Quotation after the foreword of the 2012 (posthumously) edited work by Günther Schwarz : Schauungen der Therese Neumann from Konnersreuth .

- ^ Josef Hanauer: Konnersreuth as a test case. Critical report on the life of Therese Neumann . Manz, Munich 1972, chap. VIII., Para. 5.

- ↑ Christian Feldmann: Delusion or Miracle? , P. 140.

- ↑ Mark Benecke: Blessed DNA analysis. Forensic doctors review a Christian miracle. Süddeutsche Zeitung No. 33/2004 (February 10, 2004), p. 9.

- ^ Josef Hanauer: Konnersreuth as a test case. Critical report on the life of Therese Neumann . Manz, Munich 1972.

- ^ Josef Hanauer: The Konnersreuth swindle - a scandal without end? Self-published in 1989.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Neumann, Therese |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Resl from Konnersreuth |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Bavarian peasant girl |

| DATE OF BIRTH | April 8, 1898 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Konnersreuth |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 18, 1962 |

| Place of death | Konnersreuth |