Reich Labor Service

The Reich Labor Service ( RAD ) was an organization in the National Socialist German Reich . The law for the Reich Labor Service was enacted on June 26, 1935. § 1 (2) was: "All young Germans of both sexes are required to serve their people in the Reich Labor Service." § 3 (1) read: "The Fuehrer and Reich Chancellor determines the number of annually convened conscripts and sets the length of service . “First, young men (before their military service ) were called up for six months for labor service. From the beginning of the Second World War , the Reich Labor Service was extended to include young women.

The Reich Labor Service was part of the economy in National Socialist Germany and part of education under National Socialism. After the assassination attempt on July 20, 1944 and the command over the reserve army , which was then transferred to the Waffen-SS , the RAD was given the 6-week basic military training on rifles in order to shorten the training time with the troops. The seat of the Reich leadership of the Reich Labor Service was Berlin - Grunewald .

Idea and foundation

The idea of a “compulsory women's service” is not a new phenomenon of the time of National Socialism ; this was discussed in Germany by the bourgeois women's movement even before the First World War .

The idea of a national compulsory labor service, the Nazi leaders had made Bulgaria adopted, which had introduced in 1920 a compulsory service, 30% of the age group of the population were taken to a year to nonprofit to carry out work. The Bulgarian example was observed in Germany in conservative and also in left-wing circles; the effects of 'civic upbringing' and 'physical training' were particularly well received.

In Germany, the Brüning I government introduced a “ Voluntary Labor Service ” (FAD) in the summer of 1931 , which was intended to help reduce the high level of unemployment caused by the global economic crisis . The measure had little effect; some of the resulting camps were misused as paramilitary training camps for forces hostile to the republic.

The right-wing parties, including the NSDAP , had repeatedly called for compulsory labor since the beginning of the economic crisis; the FAD was thus not least a concession to rights.

By the emergency ordinance of June 5, 1931, the promotion of the FAD became the task of the Reichsanstalt für Arbeit (founded in 1927) . Since the same ordinance involved significant reductions in benefits and the exclusion of young people under the age of 21 in particular, the “voluntariness” of the FAD only applied to those who could afford to reject it from the start. Non-profit and additional work that could not be provided through emergency work - another employment program - was eligible for funding under the FAD. The focus was on work that served to improve the soil , restore settlement and allotment areas, improve local traffic and improve public health . The work could only be carried out by corporations under public law and associations or foundations that pursued charitable goals. The duration of employment for most of the sponsored people was less than ten weeks. Before 1933 half were under 21 years old; In 1932 the FAD was opened to women. Not even a quarter of the service providers were in their legal position comparable to the free wage employment relationship; more than 75% were exempt from all norms of labor, social and collective bargaining law (a disenfranchisement of workers).

If you look closely , there was, for example , a nationalized camp of the "Voluntary Labor Service", the Voluntary Labor Service of the City of Coburg, in the Franconian city of Coburg, organized and nationalized by the municipality already governed by the NSDAP, even before Hitler came to power . Male youths were in January 1932 in a barracks in the desert Ahorner forest in order to "temporary employment and education" barracks . The main principle: “No welfare support without work”. The receipt of social benefits was thus directly linked to the plight of those affected.

In the case of Coburg, part of the amounts went to people in need determined by the city council ; the rest was deposited into a savings account. An average of 60 men were then usually in the camp after six months. There was military hierarchy, guard duty, marches, drill exercises and paramilitary drills . Refusal to serve resulted in dismissal. The Nazi propaganda made the Coburg labor service reaching far known as an idea of the party. Many local politicians from other communities came on a briefing. In September 1932, however, this work camp, which was run by the paramilitary authority of the municipality, was incorporated into the Reich's voluntary labor service , as it was subsidized to 90%. The bill worked out well for the party, as the Coburg labor camp even helped to finance the city's welfare system . Later it was considered the prototype for the Reich labor camps of the Third Reich .

Adolf Hitler , who had just been appointed Chancellor , announced on February 1, 1933 in his first radio address that the idea of compulsory labor was a “cornerstone” of his government program. His representative Konstantin Hierl presented a concept on March 1, 1933, which envisaged the transfer of the state-sponsored voluntary labor service into a “state labor service on a voluntary basis” “without delay”. The difference for him was revealed by the formulation to expand this FAD now as a “separate Reich organization with a structure similar to that of the Reichswehr ”. The structures of the authorities should also be similar to those of the Reichswehr: The duties and official powers of the State Secretary for Labor Service should be regulated in such a way "that they correspond to those of the Chief of Army Command in his official relationship with the Reichswehr Minister."

From the beginning, the aim was to introduce compulsory labor service. The fact that this did not happen as early as 1933 was due to foreign policy considerations, since the drafts that could be expected from compulsory labor service would have resulted in a magnitude that could have been used for military purposes. This led to the intervention of the disarmament conference in Geneva , which was initially taken into account by the German side. At first, the labor service was only generally redesigned according to our own ideas.

One of the clear goals was to circumvent the military restrictions of the Versailles Treaty . Obvious suspicions or even reports that military training was taking place in the RAD camps were censored by instructions. On August 3, 1933, the Thuringian Ministry of the Interior wrote to the city and community boards and district gendarmerie stations: “The police administrations are instructed to refrain from anything in the reports intended for the public, as well as in official announcements, which could be taken from as if in the labor camps military training would take place. "

In the course of the harmonization process since March 1933, attacks against labor camps of other providers increased. In this regard, the SA stood out in particular as the auxiliary police; she was also often the instigator of violent incorporations. Social democratic institutions as well as Protestant and Catholic organizations were affected by such riots.

The synchronization of all labor service providers took place in many ways up to August 1933. The initial acts of violence resulted in “self-alignment” and “voluntary” connections. This was followed by legal steps that subsequently legitimized and expanded the status quo . This synchronization of the FAD in 1933/34 with its conversion from a state-sponsored to a state, paramilitary institution was the actually significant turning point in the history of labor services worldwide. The later statutory compulsory national labor service, which came in 1935, was outwardly similar to the compulsory labor in other states.

After the Nazi regime came to power , Franz Seldte , former leader of the Stahlhelm Association , was appointed Reich Labor Minister and Konstantin Hierl was assigned to him as State Secretary . As part of the ministerial tasks, Hierl was also commissioned to form a voluntary labor service. Hierl, who was striving for his independence and the independence of the labor service, which he was denied in the Reich Labor Ministry, tried to attach the organization to another ministry where his ideas could be realized. He succeeded in 1934 with Wilhelm Frick , the Reich Minister of the Interior , who gave him a free hand. With this change, Hierl initially received the title of " Reich Commissioner for Voluntary Labor Service" before he was named " Reich Labor Leader" by the law for Reich Labor Service enacted on June 26, 1935, when voluntary service was converted into compulsory service . From now on, all male adolescents over the age of 18 had to fulfill their service obligations by their 25th at the latest. A separate regulation was provided for female youth; the statutory introduction of their compulsory service did not take place until 1939. The law always spoke of “all” young people, but it contained significant exceptions: According to § 7, it should be excluded “who is of non-Aryan descent or is married to a person of non-Aryan descent.” Should there be individual cases with "well-worthy non-Aryans", they should "in no way be used as superiors ..."

Arbeitsdienstführer Hierl commented on the FAD man in 1935: “This type of work man forged by us is the result of a fusion of the three basic elements: soldierhood, peasantry and working class.” The order mentioned and the complete diversity of occupational profiles seem remarkable or revealing today . The three terms can be seen as Nazi synonyms for discipline, income from “blood and soil” and a sense of duty.

As early as June 1933, a week after a billion Reichsmarks had been announced for the job creation program of State Secretary Fritz Reinhardt , Reichsbank President Hjalmar Schacht , Hitler's confidante Hermann Göring and Reichswehr Minister Werner von Blomberg agreed on the strictly secret budget framework for arming the Wehrmacht : 35 billion Reichsmarks, spread over eight years, with four years being used to build up defense capacity and another four years to create an offensive army . Labor market policy and armaments have been closely related to one another since the seizure of power. The scale of armament (as well as its long-term nature and strategic importance) dwarfed everything that had ever been discussed in terms of combating unemployment. Between 1933 and 1939 the Nazi state spent around 60 billion Reichsmarks for military purposes, but generally only 7–8 billion Reichsmarks for civilian purposes. From the very beginning, the RAD focused on the military purpose of preparing for war.

Until the end of the war, people doing labor received uniformly for their hard physical work z. B. in road construction and settlement construction as well as in the quarry 21 Reichsmarks per week. This corresponded to the unskilled labor wages for young professionals at the beginning of the 1930s. Of this, only RM 0.50 was paid out daily; that was half of the soldiers' military pay . The rest of the money was kept for food, camp accommodation, heating, clothing and insurance. The money came from the projects in which the RAD was used.

function

The Reich Labor Service fulfilled several tasks within the National Socialist system. The official purpose was stated in Section 1 of the Law on the Reich Labor Service:

“The Reich Labor Service is honorary service to the German people . All young Germans of both sexes are obliged to serve their people in the Reich Labor Service. The Reich Labor Service is supposed to educate the German youth in the spirit of National Socialism to the national community and to the true work ethic, above all to the due respect for manual labor. The Reich Labor Service is intended to carry out charitable work. "

The RAD had several goals. 1. A main goal was to discipline the young generation, their relatives during the Great Depression had been unemployed for years often. The paramilitary structure of the RAD corresponded to this. Konstantin Hierl coined the very telling term “soldier of work” as early as 1934 for those doing labor service. 2. The RAD was an attempt to put the National Socialist ideology of the national community into practice. Konstantin Hierl emphasized this aspect in his speeches: "There is no better way to overcome social divisions, class hatred and class arrogance than if the son of the factory director and the young factory worker, the young academic and the farmhand in the same coat To do the same service with the same food as an honorary service for the people and fatherland common to them all. " 3. The economic importance of the labor service, on the other hand, was low because of poor labor productivity. 4. Finally, from 1938 onwards, the RAD increasingly took on auxiliary services for the Wehrmacht.

After that, the RAD was part of the National Socialist education system in its beginnings . Compulsory labor service was a prerequisite for admission to university studies . Applicants who were not considered fit for work for health reasons had to do a “student compensation service”, which was organized by the Reichsstudentenführung .

A side effect was that previously unemployed RAD members were no longer recorded in the unemployment statistics.

Section 14 of the Reich Labor Service Act of June 26, 1935 stipulated that membership of the RAD “did not constitute an employment or service relationship within the meaning of labor law and Section 11 of the Ordinance on Duty of Care”. Labor laws and regulations on occupational health and safety, the Works Council and Labor Court Act and the right to support in the event of illness did not apply to the Reich Labor Service. Apparently, one goal was to allow young people to work as cheaply as possible, under the collective bargaining agreement, and under duress and intimidating military discipline.

The RAD exaggerated work for " honorary service " at the " national community ". This claim became particularly explosive and ideologically paradoxical when forced laborers, prisoners or prisoners from labor education camps, i.e. “ non-community members ”, were used on projects and construction sites on which the RAD was working .

commitment

The Reich Labor Service was used for various tasks. One of the first operations of the RAD in 1933 was its participation in the construction of the Dachau concentration camp . This also shows that the RAD was never an apolitical institution. Before the Second World War, he dealt with forestry and cultivation as well as dike building or drainage tasks and activities in agriculture . An important focus was the - albeit not very effective - use in the Emsland districts to reclaim the huge moorland and heather areas ( Emsland cultivation ), on which new farms were to be built as part of the self-sufficiency policy . There was only sporadic construction work on the Reichsautobahn , e.g. B. in the Frankfurt a. M .; In contrast, clearing work for later motorway work was carried out in some areas of Germany. However, the RAD did not even achieve 50% work performance compared to the private sector . According to Wolf Oschlies , this development is not a coincidence. Rather, all conceivable variants of a labor service would have to struggle with the same problem: "Anyone who [...] gathers large groups of people to work together in an economic predicament is confronted with an economic problem sui generis: The effort for organization, accommodation, transport, supply, etc. increases If at all, only 'calculate' it as a countable yield after some time. Labor services are not worth it! So you will emphasize their secondary effects and emphasize their community-building, socially integrating, working, patriotic, etc. role. "

Above all, the insufficient work performance of the RAD was a thorn in the side of Hermann Göring as well as the "General Inspector for German Roads", Fritz Todt . Objectively, the service did not make any substantial contributions to overcoming the economic and labor market crisis, although around three million men passed through the RAD between 1933 and 1940. At the same time, the myth is alive that the National Socialists defeated unemployment in Germany by “getting unemployed people off the streets” and giving them work in the labor service.

The lower the unemployment rate, mainly as a result of the boost in the armaments industry (it fell from 6 million in 1933 to a remainder of 350,000 within three years), the less important the RAD became in Germany as a job creation measure. The cohorts who were due to serve in the RAD at that time were born during the First World War and in any case comprised only 300,000 to 400,000 men. The reintroduction of conscription on March 16, 1935 also thinned the labor market. Conscription initially lasted a year and was extended to two years in August 1936. However, the City of Vienna points out on a page published by it that of the 183,271 unemployed registered in the capital of Austria in January 1938, after Austria's annexation to the German Reich in March 1938, many had also found work by joining the Reich Labor Service.

From 1938 onwards, education in the RAD took a back seat. Now the construction of air raid shelters, airfields and positions on the west wall and east wall dominated . Initially, the RAD did not specifically seek military projects. The drainage and embankment of the Sprottebruch between Sprottau / Sprottischwaldau and Primkenau (Lower Silesia) is an example of this, a new settlement "Hierlshagen" near Primkenau was named after the Reich Labor Leader Konstantin Hierl. In Hierlshagen (Ostaszow in Polish) four RAD departments were barracked at the same time. From 1938 onwards, the RAD gradually transformed into the "Wehrmacht construction team". The fact that the RAD now had to provide construction battalions for the Wehrmacht can be defined as a further turning point.

During the Second World War, the RAD was used more and more for important military construction tasks in the vicinity of the fighting troops. From the war year 1942 onwards, the RAD only eked a “shadowy existence” in the Reich on the fringes of the Wehrmacht. The RAD was already completely absorbed in the war machine.

From 1942 onwards, the conscripted class of 1924 was used for the Eastern campaign immediately behind the front to build military installations and to build roads and bridges. There was also contact with the enemy with human losses. In October 1942, after the six-month RAD service had expired, the RAD units deployed in the occupied territories of the Soviet Union were almost completely transferred to field training regiments of the Army (this was where the recruit training usually carried out at home took place in the occupied Soviet territory; thus avoided the recruits were transported back to Germany and could be used against partisan groups at the same time ). The RAD leaders, on the other hand, returned to the Reich. In 1942 the RAD was completely stripped of its original concept and deployed as a semi-military combat force. From 1943 onwards, no more RAD units were deployed on the Eastern Front, as was the case with the 1924 RAD conscription class.

From 1943 were independent from RAD departments Flak - batteries formed. The crews received full anti-aircraft training in the Air Force and manned the guns in RAD uniform. Other departments, together with the Todt Organization , built beach barns and smaller bunkers on the Atlantic ( Atlantic Wall ) and on the Mediterranean. Many departments were also used for development work for relocated armaments production in the Reich and for repairing damage after air raids on German cities.

After the appointment of Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler as chief of the replacement army as a security measure after the assassination attempt on Hitler on July 20, 1944 , the RAD was given basic military training (training for recruits). In view of the losses on the fronts, this measure served to strengthen personnel by saving the Wehrmacht's training units and their personnel, as well as those who had been militarily trained at the RAD, were available for use at the front. As a result of this measure, conscripts who had previously been released from the labor service were now drafted into the RAD after all.

Towards the end of the war, units of the male RAD should also be deployed as part of the Volkssturm . Hierl prevented this and tried to form independent RAD combat groups. Three RAD infantry divisions that were deployed in the 12th Army in the final battle for Berlin became known. Due to high losses in the installation room and very poor armament, they could not have any significant influence on the events around Berlin.

The female RAD was used as a substitute for the lack of male workers in agriculture and as a so-called war aid service (KHD) in offices and offices, in armaments production and in local public transport. Women could also become military assistants (synonymous with 'lightning girls'). To this end, the working hours were extended by half a year. From 1944 onwards, “Arbeitsmaiden” of the RAD for female youth were also used to operate anti-aircraft searchlights for the control of anti-aircraft guns and night fighter units of the Luftwaffe. A “military service” planned by the RADwJ shortly before the end of the war, to which 250,000 to 300,000 women were to be drafted, did not take place in the planned form.

- Application examples Reich Labor Service (RAD)

RAD department 2-105 "Thomas Trautenberger", Sprottischwaldau (Szprotawka) in Lower Silesia, Sprottebruch - drainage

Length of service

The period of service for men between the ages of 18 and 24 was initially six months; the period of service preceded the two-year military service. In the course of the Second World War it was continuously shortened and in the end was only six weeks, which from mid-1944 were used exclusively for basic military training.

For women, the service period has been six months since 1939, but this was often extended by an emergency service obligation . In July 1941 the period of service was extended by the military service by a further six to twelve months, in April 1944 it was extended to 18 months and finally in November 1944 it was completely extended. The additional forces gained through the extension of service in 1944 were mainly deployed as anti-aircraft helpers .

During the labor service, the "workmen" and "workmaiden" lived barracked in so-called camps.

Uniformity

A uniform paramilitary uniform was introduced in early 1934. Earth brown was chosen as the color for men and women. The uniform of the male members of the Reich Labor Service included a swastika armband , which was worn on the upper left sleeve under the spade with the department name. The legend goes that Hierl was strictly against the introduction of the swastika, but Hitler forced him to do so in exchange for the relative independence of the RAD in the Reich Ministry of the Interior . The dress uniform included a cap with an arched length and a peak , called "ass with a handle" by the labor service officers.

A distinctive feature for the worker was the spade. It documented the physical work, but was also a kind of "spare rifle" in relation to the Wehrmacht. Analogous to the “gun-handle-knocking” in the Wehrmacht, the RAD had the “spade handles”.

During the war, special cuffs were used by special units (e.g. those with the inscription " war reporter ", "patrol") that were worn in addition to the armband. There were also cuffs for the Emsland departments, the departments deployed on the Ostwall and Westwall , and special cuffs with the names of battles in the Russian campaign when RAD men were involved in direct combat operations on the front. RAD units stationed directly behind the Eastern Front in Poland in 1945 wore yellow armbands with the black imprint "Im Einsatz - Deutsche Wehrmacht".

The female members of the RAD did not officially wear cuffs. In some areas of Germany, sleeve bands were created for special uses, but they were not universally accepted. The label on the tape indicated the particular service position of the obligated person, for example "RAD-Kriegshilfsdienst", " KHD-Straßenbahn " or similar.

Leisure time and life situation

The daily routine with its detailed duty rosters left the RAD workers with little time at their own disposal and was similar to that of the soldiers: Without a midday rest, the pure duty time per week added up to around 76 hours. In addition, there was practically no retreat in the limited free time. Evenings were usually planned, and there was generally no provision for leaving the camp outside of office hours; this required - as with the military - special permission. The RAD completely replaced the previous social environment. In this way, a collective identity should be developed in the new “community”.

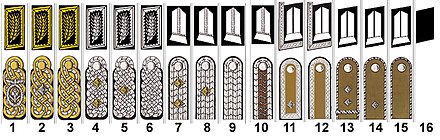

Ranks

Like all National Socialist organizations, the Reich Labor Service was structured strictly hierarchically and followed the Führer principle . The ranks of the members of the Reich Labor Service in descending order:

- Sleeve badge work drill, left upper arm

In terms of rank, the sub-squad leader differed from the chief foreman only through his ten-year commitment as a leader at the RAD. While the chief foreman was released after his six-month service, the sub-squad leader remained in the camp as a trainer. From this rank upwards, the labor service leaders received a salary corresponding to the comparable service ranks of the Wehrmacht (see NS rank structure ).

organization structure

Male youth

At the head of the 33 Arbeitsgaue was a Arbeitsgaufführer in the rank of General or Oberstarbeitsführer. His Gaustab (Arbeitsgauleitung) was subordinate to him.

| Number of the district | Name of the working district | Headquarters of the Arbeitsgauleitung | Traditional badge on the hat |

Description traditional badge |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. | East Prussia | Königsberg in Prussia | Black swastika with a narrow silver border and the black knight's cross on a white shield. This badge was supposed to symbolize the historical continuation of the achievements of the Teutonic Order by the RAD. | |

| II | Gdansk West Prussia | Danzig | ||

| III | Wartheland-West | Poses | ||

| IV | Pomerania East | Stolp in Pomerania | In the middle of the Pomeranian griffin on a vertically divided blue-silver base plate . | |

| V | Pomerania West | Szczecin | Based on a Viking jewelry found near Hiddensee ( Hiddensee gold jewelry ) which was worn in gold-metal design as an intertwined knot. | |

| VI | Mecklenburg | Schwerin | Based on the example of a Germanic swastika fibula of the 2nd / 3rd centuries. Jhs. AD from the district of Ludwigslust-Parchim. Rounded shape of the swastika after the shape of the sun wheel , in the center of which lies a buffalo head, the coat of arms of Mecklenburg, on a white mirror. Like the original, the swastika itself was made of gold-metal, while the mirror was replaced by a modern design in white with the Mecklenburg bull's head in black, silver and red. | |

| VII | Schleswig-Holstein | Kiel | ||

| VIII | Ostmark | Frankfurt Oder | ||

| IX | Brandenburg | Berlin-Friedenau | ||

| X | Lower Silesia | Goerlitz | ||

| XI | Central Silesia | Wroclaw | Stylized Silesian eagle, from the coat of arms of Silesia from the Piast era. He wears a rising silver moon on his chest. The eagle itself is armed in black and red. (Catches, beak) | |

| XII | Upper Silesia | Opole | ||

| XIII | Magdeburg-Anhalt | Dessau-Ziebigk | ||

| XIV | Halle-Merseburg | Hall | ||

| XV | Saxony | Dresden | White shield with two green crossed swords based on the Saxon coat of arms. | |

| XVI | Westphalia North | Muenster | ||

| XVII | Lower Saxony-Mitte | Bremen | ||

| XVIII | Lower Saxony East | Hanover | Two crossed horse head beams in the style of the Low German hall house . The swastika under the intersection of the bars. Made of bronze-colored metal. | |

| XIX | Lower Saxony-West | Oldenburg i. O. | ||

| XX | Westphalia-South | Dortmund | ||

| XXI | Lower Rhine | Dusseldorf | ||

| XXII | North Hessen | kassel | Badge refers to the wealth of forests in Hesse in the form of an oak break. | |

| XXIII | Thuringia | Weimar | ||

| XXIV | Middle Rhine | Koblenz-Karthauser | ||

| XXV | Hesse-South | Wiesbaden | ||

| XXVI | Württemberg | Stuttgart | ||

| XXVII | to bathe | Karlsruhe | Badge refers to the abundance of forests in the Black Forest in the form of a pine wood. | |

| XXVIII | Francs | Wurzburg | ||

| XXIX | Bavaria-Ostmark | regensburg | Longitudinal oval shield in the Bavarian colors white-blue with yellow contours; in the center a symbolic representation of the Liberation Hall near Kelheim on a green promontory between the blue confluence of the Danube and Altmühl . | |

| XXX | Bavaria highlands | Munich | Long oval shield with a gentian flower and an edelweiss , with the gentian symbolizing the wide hilly landscape and the edelweiss the rocky peaks of the Bavarian Alps. The badge itself was in the colors brown, blue, white, green and gold. | |

| XXXI | Emsland | Osnabrück | ||

| XXXII | Saar-Palatinate | Munster am Stein | ||

| XXXIII | Alpine country | innsbruck | ||

| XXXIV | Upper Danube | Linz | ||

| XXXV | Lower Danube | Vienna | Edelweiss in silver or gold was used as a symbol of the combat action of alpine troops, who already wore this symbol in the First World War. | |

| XXXVI | Südmark | Graz | ||

| XXXVII | Sudetenland West | |||

| XXXVIII | Sudetenland East | Prague | This badge with a red background combines the symbols of the countries of Bohemia , Moravia and the former Austrian Silesia . The Prague Roland on Charles Bridge in Prague, both symbols silver-plated, symbolized the struggle for space over the old German law. The waves below were gray and the heraldic shields in black and red. |

After the attack on Poland in October 1939 and the reintegration of the German territories until 1919, the Reichsgau Wartheland was created . The Arbeitsgau 3 was established there with the management headquarters in Schwaningen near Posen . Labor camps were set up in the then so-called places Hohensalza , Wongrowitz and Dietfurt . All of the 1924 conscripts from Hamburg were trained there for use in the occupied territories of the Soviet Union with both spades and carbines. The order designations of the departments were preceded by a K (for war or war effort). The unit stationed in Dietfurt and trained for use in the east (front) was given the designation K 4/36.

Female youth

There were no special offices in the Reichsleitung for the labor service for the female youth, but departments that were subordinate to the heads of office of the Reichsleitung. The realm was divided into 13 district leaderships.

(This is obviously an old structure, obsolete by a new one - see above; because the working districts were responsible for both male and female youth.)

| District number | Name of the district | Headquarters of the district management |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | East Prussia | Königsberg in Prussia |

| 2 | Pomerania | Szczecin |

| 3 | Nordmark | Schwerin in Mecklenburg |

| 4th | Kurmark | Berlin |

| 5 | Silesia | Wroclaw |

| 6th | Central Germany | Weimar |

| 7th | Saxony | Dresden |

| 8th | Lower Saxony | Hanover |

| 9 | Westphalia | Dortmund |

| 10 | Rhineland | Koblenz |

| 11 | Hesse | Wiesbaden |

| 12 | Southwest Germany | Stuttgart |

| 13 | Bavaria | Munich |

General

The approximately 30 working districts of the RAD each consisted of 4 to 12 RAD "groups", which in turn headed 5 to 15 departments. The most important unit in the male RAD was the department, which was housed in a closed barrack camp. Theoretically, a department consisted of 216 workers and leaders.

During the war, sections and areas that comprised several groups were created based on regional military needs. In accordance with the war situation, these organizational structures were dissolved again after the tasks had been completed. The “Higher RAD Leaders” (HRADF) represented a special form of leadership structure. These high leaders temporarily commanded several groups, areas or sections. So existed e.g. B. in the occupied territories of the Soviet Union the "HRADF H V", General Labor Leader Dr. Wagner, who supported Army Group Center with 3 sections and up to 16 groups. HRADF was present in all theaters of war.

The End

After the end of the war, the Reich Labor Service was banned and dissolved by the Control Council Act No. 2 , and its property was confiscated.

foreign countries

In France of the Vichy regime, based on the Reich Labor Service, v. a. To support the German war economy, the Service du travail obligatoire (STO) (= "compulsory labor service") was founded in February 1943 .

See also

- Labor army

- Bevin Boys

- Civilian Conservation Corps

- Service award for the Reich Labor Service

- Service for Germany

- NS ranks

- Nazi forced labor

literature

- Wolfgang Benz : From Voluntary Labor Service to Compulsory Labor Service. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 16 (1968) 4, pp. 317–346 ( PDF ).

- Rainer Drewes: Labor service in the Emsland moor. A vision, its abuse and its end : On books for young people by Peter Martin Lampel (1932) and Heinz Ludwig Renz (1938). In: Yearbook of the Emsländischen Heimatbund vol. 52/2006, Sögel 2005, pp. 177–193.

- Peter Dudek: Education through work. Labor camp movement and voluntary labor service 1920–1935. Opladen 1988.

- Hubert Gerlich: The new province of the Führer - The Reich Labor Service in Emsland (1935-1938). In: Yearbook of the Emsländischen Heimatbund, Vol. 53/2007, Sögel 2006, pp. 98–114.

- Josef Hamacher: Voluntary Labor Service and Reich Labor Service in the old district of Meppen. In: Yearbook of the Emsländischen Heimatbund, Vol. 48/2002, Sögel 2001, pp. 273-306.

- Michael Hansen: Idealists and failed existences. The leadership corps of the Reich Labor Service. Diss., University of Trier, 2004 ( PDF ).

- Detlev Humann: "Labor battle". Job creation and propaganda in the Nazi era 1933–1939 . Wallstein, Göttingen 2011, ISBN 978-3-8353-0838-1 .

- Michael Jonas: On the glorification of Prussian history as an element of intellectual war preparation 1933–1945 in Germany. Organizationally shown in the education system of the Reich Labor Service. Potsdam 1992. (Dissertation)

- Heinz Kleene: The Voluntary Labor Service (FAD) in Emsland. In: Yearbook of the Emsländischen Heimatbund, Vol. 48/2002, Sögel 2001, pp. 307-330.

- Henning Köhler : Labor Service in Germany. Plans and forms of implementation up to the introduction of compulsory labor in 1935 . (Writings on economic and social history; Vol. 10). Berlin 1967.

- Michael Mott : The activity of the Reich Labor Service. In: Monograph 175 years of the Fulda district , history and tasks of the Fulda district. Fulda 1996, ISBN 3-7900-0271-2 .

- Kiran Klaus Patel : soldiers at work. Labor services in Germany and the United States, 1933–1945. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Verlag, Göttingen 2003, ISBN 3-525-35138-0 . (Engl: Soldiers of Labor. Labor Service in Nazi Germany and New Deal America, 1933–1945, Cambridge University Press, New York 2005. Review by Nicole Kramer at H-Soz-u-Kult , 2005.)

- The Reich Labor Service. In: Wolfgang Stadler: Hope homecoming. Swing-Verlag, Colditz 2000, ISBN 3-9807514-0-6 , Chapter 2 (By bike to Stalingrad).

- Reinhold Schwenk: Spiritual and material foundations of the formation of the leader corps in the labor service and its conformity and reorganization after 1933. Düsseldorf 1967. (Dissertation)

- Manfred Seifert: Cultural work in the Reich Labor Service. Theory and practice of National Socialist cultural maintenance in the context of historical-political, organizational and ideological influences. (International university publications; Vol. 196). Münster / New York 1996.

Web links

- Youth in Germany 1918 to 1945: Reich Labor Service (NS Documentation Center of the City of Cologne)

- Literature on the Reich Labor Service in the catalog of the German National Library

- Reich Labor Service Act (RGBl. I, 1935, p. 769)

- Wolf Oschlies: The Reich Labor Service (RAD) at Shoa.de

- Michael Hansen: "idealists" and "failed existences". The leadership corps of the Reich Labor Service. Dissertation, University of Trier, 2004 (PDF; 2.4 MB)

- The Reich Labor Service and Reich Labor Service as part of the life stations at the German Historical Museum

Individual evidence

- ^ Decree of August 20, 1943

- ^ Johannes Steffen: Emergency work - care work - compulsory work - voluntary labor service. Publicly funded or forced employment in the Weimar Republic - 1918/19 to 1932/33. (Manuscript) Bremen, June 1994.

- ↑ Wolf Oschlies: The Reich Labor Service (RAD). RAD - youth with a spade . Working group “The future needs memories”. October 15, 2004, revised July 8, 2017

- ^ Johannes Steffen: Emergency work - care work - compulsory work - voluntary labor service. Publicly funded or forced employment in the Weimar Republic - 1918/19 to 1932/33. (Manuscript) Bremen, June 1994, p. 83 ff.

- ^ Johannes Steffen: Emergency work - care work - compulsory work - voluntary labor service. Publicly funded or forced employment in the Weimar Republic - 1918/19 to 1932/33. (Manuscript) Bremen, June 1994, p. 84 ff.

- ^ Joachim Albrecht: The avant-garde of the "Third Reich". The Coburg NSDAP during the Weimar Republic 1922–1933. Frankfurt am Main 2005, p. 157.

- ↑ a b c d Manfred Weißbecker: The Reich Labor Service Act of June 26, 1935 and its long history.

- ↑ Kiran Klaus Patel: "Soldiers of Work". Labor services in Germany and the USA 1933–1945. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2003, ISBN 978-3-525-35138-3 , pp. 73 ff.

- ↑ Kiran Klaus Patel: "Soldiers of Work". Labor services in Germany and the USA 1933–1945. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2003, ISBN 978-3-525-35138-3 , p. 159 ff.

- ^ Emergency work Voluntary Labor Service (FAD) Reich Labor Service (RAD). Retrieved September 4, 2012 .

- ↑ a b c Kiran Klaus Patel: "Soldiers of Work". Labor services in Germany and the USA 1933–1945. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2003, ISBN 978-3-525-35138-3 .

- ↑ Kiran Klaus Patel: "Soldiers of Work". Labor services in Germany and the USA 1933–1945. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2003, p. 117 f.

- ↑ Adam Tooze: The totalitarian state. Economy of horror. Spiegel Special History 1/2008.

- ↑ Christoph Wagner: Development, rule and fall of the National Socialist movement in Passau from 1920 to 1945. Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-86596-117-4 , p. 308.

- ↑ Manfred Weißbecker: Two laws - one goal. Junge Welt, June 26, 2010.

- ^ Reich Labor Service Act of June 26, 1935

- ↑ Kiran Klaus Patel: "Soldiers of Work". Labor services in Germany and the USA 1933–1945. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2003, p. 337.

- ↑ Quotation in: Michael Grüttner : Students in the Third Reich, Schöningh, Paderborn 1995, p. 227.

- ↑ Kiran Klaus Patel: "Soldiers of Work". Labor services in Germany and the USA 1933–1945. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2003, p. 368.

- ↑ Michael Grüttner : Students in the Third Reich, Schöningh, Paderborn 1995, p. 227.

- ↑ Kiran Klaus Patel: "Soldiers of Work". Labor services in Germany and the USA 1933–1945. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2003, ISBN 978-3-525-35138-3 , p. 404.

- ↑ Kiran Klaus Patel: "Soldiers of Work". Labor services in Germany and the USA 1933–1945. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2003, ISBN 978-3-525-35138-3 , p. 318.

- ↑ Kiran Klaus Patel: "Soldiers of Work". Labor services in Germany and the USA 1933–1945. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2003, ISBN 978-3-525-35138-3 , p. 402.

- ↑ Wolf Oschlies: The Reich Labor Service (RAD). RAD - youth with a spade . Working group “The future needs memories”. October 15, 2004, revised July 8, 2017

- ↑ Kiran Klaus Patel: "Soldiers of Work". Labor services in Germany and the USA 1933–1945. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2003, ISBN 978-3-525-35138-3 , p. 317.

- ↑ Kiran Klaus Patel: "Soldiers of Work". Labor services in Germany and the USA 1933–1945. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2003, ISBN 978-3-525-35138-3 , pp. 196, 399, 155, 185.

- ↑ Wolfgang Benz: Nazi myths that Germans still believe in. Myth 2: Hitler beat unemployment . The world . October 21, 2007

- ↑ dhm.de

- ^ Unemployment in the Vienna History Wiki of the City of Vienna

- ↑ Kiran Klaus Patel: "Soldiers of Work". Labor services in Germany and the USA 1933–1945. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2003, ISBN 978-3-525-35138-3 , p. 363.

- ↑ Kiran Klaus Patel: "Soldiers of Work". Labor services in Germany and the USA 1933–1945. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2003, ISBN 978-3-525-35138-3 , p. 400.

- ↑ Kiran Klaus Patel: "Soldiers of Work". Labor services in Germany and the USA 1933–1945. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2003, ISBN 978-3-525-35138-3 , p. 117 f.

- ↑ Kiran Klaus Patel: "Soldiers of Work". Labor services in Germany and the USA 1933–1945. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2003, ISBN 978-3-525-35138-3 , pp. 190 f.

- ^ Henrik Schulze: The RAD infantry division "Friedrich Ludwig Jahn" in the gap between 9th and 12th Army. The Mark Brandenburg in the spring of 1945. Meißler, Hoppegarten near Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-932566-45-5 .

- ↑ The Reich Labor Service. Retrieved September 4, 2012 . P. 27.

- ↑ Kiran Klaus Patel: "Soldiers of Work". Labor services in Germany and the USA 1933–1945. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2003, ISBN 3-525-35138-0 , p. 215 ff.

- ↑ Kiran Klaus Patel: "Soldiers of Work". Labor services in Germany and the USA 1933–1945. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2003, ISBN 978-3-525-35138-3 , p. 209 ff.