Dutch East India Company

The Dutch East India Company ( Dutch Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie ; Vereenigde Geoctroyeerde Oostindische Compagnie , abbreviated VOC or Compagnie for short ) was an East India Company , to which Dutch merchant companies merged on March 20, 1602 in order to eliminate competition with one another. The VOC received trade monopolies from the Dutch state as well as sovereign rights in land acquisition, warfare and fortress construction. It was one of the largest trading companies of the 17th and 18th centuries.

The VOC had its headquarters in Amsterdam and Middelburg . The headquarters of the merchant shipping was in Batavia , today's Indonesian capital Jakarta on Java . Further branches were established on other islands of what is now Indonesia. A trading post was also on Deshima , an artificial island off the coast of the Japanese city of Nagasaki, and others in Persia , Bengal , now part of Bangladesh and India , Ceylon , Formosa , Cape Town and southern India.

The economic strength of the VOC was based primarily on the control of the spice route from rear India to Europe, with which it dominated part of the lucrative Indian trade . The six chambers ( Kamers structured) company was the first one that shares spent. After the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War from 1780 to 1784 , the company ran into financial difficulties and was liquidated in 1798 .

During two centuries of monopolized trade in many areas, the VOC had around 4,700 ships under sail, on which around a million people were carried. The first century accounts for about a third and the second for two thirds of both figures. The commercial value of the goods transported to Europe was 577 million guilders in the first century until 1700 and 1.6 billion guilders in the second until 1795. The VOC's competitor, the English East India Company (EIC / BEIC) founded in London in 1600 and later the British East India Company , could not prevail against the VOC. Only towards the end of the 17th century was there a brief phase during which the EIC / BEIC became a serious competitor.

The advance companies

Portuguese ships reached Indonesia at the beginning of the 16th century . They were the first to come across the route around the Cape of Good Hope . The knowledge of this sea route to Asia was reserved for Portuguese seafarers for several decades. In the last decades of the 16th century, however, Dutch cartography became the leading one in Europe. The main contribution to this was made by Dutch people like Jan Huygen van Linschoten , who had served as seamen or merchants in Portuguese service. Van Linschoten's Itinerario was not printed until 1596, but his observations and tips influenced commercial decisions shortly after his return from Southeast Asia in 1592. Based on his suggestions, the first official Dutch fleet set out for Asia in 1595 under the leadership of Cornelis de Houtman . For this trade trip to Amsterdam which was specially Compagnie van Verre been established by Governor Maurice of Orange a carte blanche had received. The four ships in the fleet represented an investment of 290,000 guilders, of which 100,000 guilders alone were to be used to buy spices in East India. The fleet, which returned to its home port in 1597, had not reached its original destination, the Moluccas , but was so economically successful that in 1598 five expeditions by various East Indian companies set out from different Dutch port cities and nine more followed over the next three years. The destination of most expeditions was Banten on Java, in 1599 one expedition also reached the Moluccas further east and parts of a fleet even reached the Banda Islands and Sulawesi . The companies that financed these expeditions were set up exclusively for the individual trips, and when the trip was over, the entire profit was realized. These so-called pre-companies (Dutch voorcompagnieën ) did not establish trading stations or continuously develop trade relations .

Very early on, there were voices against the fragmentation of Dutch merchants into competing enterprises. In particular, the " Landadvocaat " of Holland, Johan van Oldenbarnevelt , advocated a merger . Merchants from the province of Zeeland , who feared the overwhelming power of the Amsterdam merchants , resisted the merger . Associations of individual companies existed as early as 1598 and as early as 1600 the Eerste Vereinigde Compagnie op Oost-Indie was founded in Amsterdam , which was already equipped with a trade monopoly, but which was still at the urban level. This monopoly largely anticipated the later VOC privileges. In 1601 the states of Holland discussed the situation before the States General , which also spoke out in favor of a merger. After the intervention of Moritz von Oranien, the Seeländische Compagnien joined this company, so that on March 20, 1602 the federally structured VOC could be established. With Generale Vereenichde Geoctroyeerde Compagnie the VOC secured a trading monopoly ( octrooi ) limited to 21 years for the movement of goods between the Netherlands on the one hand and the area east of the Cape of Good Hope and west of the Magellan Strait on the other, the so-called octrooigebied , the trading zone, too. The VOC thus had the privilege of being the only private or legal entity in the country to be allowed to trade with East India. For this privilege, the VOC paid 25,000 guilders in 1602. In 1647 the company had to pay 1.5 million guilders for this right, and 3 million guilders each in 1696 and 1700. Unlike its British competitor, the East India Company , the VOC had dedicated sovereignty rights. This included the right to appoint governors, raise armies and fleets, erect fortresses and conclude agreements that are binding under international law. In Asia, the VOC could therefore act like a sovereign state, even if it was acting formally on behalf of the United Netherlands. Historians point out that in the age of early modern expansion, when England, France, the Netherlands, Portugal and Spain were in strong competition with one another, endowing a financially strong company with such extensive privileges ultimately represented a partial privatization of a country's military spending.

Organizational characteristics

For each of the original six companies that were merged into the VOC, a regional administration called a chamber was established. The directors of the companies merged in the VOC became the board members of the VOC. However, since eight of these seats went to Amsterdamer voorcompagnieën and the other eight to all other companies, the Zealanders continued to fear the dominance of Amsterdam. The Zeeland demand to grant every regional chamber the same voting rights, however, failed because of the resistance from Amsterdam, so that a compromise was finally found in establishing a seventeenth seat, which was to be occupied alternately by a non-Amsterdam citizen. Of the 17 delegates, Heeren XVII in Dutch , English: the Lords Seventeen , who were also bewindhebbers - active business partners, came

- eight from Amsterdam

- four from Zealand / Middelburg

- one from Delft

- one from Enkhuizen

- one from Hoorn

- one from Rotterdam and

- one alternately from Zeeland, Delft, Rotterdam, Hoorn or Enkhuizen.

The directorate composed in this way, the Heeren XVII , was to meet in Amsterdam, but a compromise had to be found with the Zeeland countries for this too. An eight-year cycle was agreed. Six years of this was the seat of the board in Amsterdam under the presidency of an Amsterdam resident and then two years in Middelburg under the direction of a Zealander. The headquarters of the VOC was located in what was later known as the Oost-Indisch-Huis on Kloveniersburgwal in Amsterdam, and another in Middelburg. The six founding companies continued to operate as regional chambers. The board of directors of the VOC thus corresponded to a federal structure that was similar to the one that had also developed politically between Holland, Zealand and the cities. An agenda sent out by the presiding chamber before the meetings allowed all chambers to give their MPs precise instructions. The meeting was interrupted for consultations between the MPs and the home chambers for unforeseen negotiation points.

The early days of the VOC

With a charter, the Dutch parliament formally guaranteed the VOC the trade monopoly for all areas east of the Cape of Good Hope and west of the Strait of Magellan. The charter established some of the company's sovereign rights and also allowed it to wage war. Admiral Steven van der Haghen, under whose leadership the VOC's first fleet set sail on December 18, 1603, had express instructions to take military action against the Portuguese in India and on the East African coasts on his voyage. Faced with an overwhelming force of twelve armed ships, the Portuguese gave up their Fort Victoria on Ambon , the most important island in the Moluccas, in 1605 without a fight . However, the most important Asian port in the early phase of the VOC initially remained the Javanese port city of Banten, which was located near the Sunda Strait. It was a planned city that developed around the commercial center, consisting of a market and port, and where traders of different ethnicities lived. Chinese traders were particularly well represented in Banten, and Turkish, Persian, Arab traders and members of various Indian ethnic groups also worked there. The main trade was in Chinese luxury goods, pepper and various spices that were grown on the Moluccas. The advance companies had initially only appeared there as a group among a number of different traders. The permanent presence of the VOC and the EIC in Banten led to a change in the balance of power between the individual groups of traders, and both the British and Dutch East India Companies tried to obtain various privileges from the Sultan of Banten. The privileges were denied, however, as it was more in the interest of the sultan to maintain the competitive situation in the port and thus to secure the importance of Banten as a trading center in the long term. Negotiations between the VOC and the EIC about a merger of the two companies failed in 1615.

The success of the VOC on Banten was aided by a major nautical discovery. The VOC captain Hendrik Brouwer steered his ships in 1611 after the stop at the Cape of Good Hope not with the summer monsoon winds in a northeasterly direction, but sailed 4,000 nautical miles at about 40 ° south latitude to the east and then turned about 110 east Longitude for another 2000 nautical miles to the north. While the usual monsoon route to Java took almost a year of sailing time, Henrik Brouwer arrived in Batavia after five months and twenty-four days. Dirk Hartog came off course in a storm in 1616 with the ship Eendracht and, driven by the westerly winds, arrived at Ambon on a similar course in December 1616. However, the following ships on this route occasionally stranded on the offshore reefs of the as yet unknown continent of Australia, for example in 1629 when the Batavia was lost .

The first shares

The privileges that the Dutch state had granted the VOC were limited in time, but far less limited than a single trade expedition would have been. In practice, the use of the privileges required a considerable financial outlay, which the individual chambers were not able or willing to bear. The end of the pre-company, which was geared towards single journeys to a continuously operating East India Company, required the creation of a solid capital stock.

The directors of the VOC decided to finance the company for the first time ever by issuing shares. While previous financings corresponded to medium-term bonds , i.e. related to shiploads, the shareholders ( participants ) of the VOC remained tied to their system for ten years. After the interest-bearing repayment in 1612, the shareholders were then given the opportunity to subscribe for a further ten years. There was also a dividend payment . Beyond that, however, the shareholders had no say in the VOC. This hardly changed in 1622/23 when the company's rights were extended for another twenty years. In 1602, investors put 6.5 million guilders in the VOC, today's equivalent of around 100 million US dollars . The VOC thus had a larger and more stable capital base than the EIC. The Dutch also had better nautical and geographic knowledge. Even if the VOC was founded after the EIC, the previous companies also had extensive trading contacts in the Asian region. This made it possible to finance extensive military operations in Asia, which secured the monopoly in the Moluccan spice trade. In 1622, after the conquest of the Banda Islands, the monopoly for nutmeg and mace was added, and later that for cloves . After the Portuguese were expelled from Ceylon, cinnamon was also traded. According to historian Jürgen Nagel , the British East India Company would probably have perished as early as the 1680s if the East India Companies had focused exclusively on the spice trade with the Malay Archipelago. As it was, the EIC concentrated primarily on trade in India .

The founding of Batavia

The Amsterdam directors decided early on to set up a central trading center in Southeast Asia. The company's strategic goal was to control the export of spices from the Moluccas. Banten was unsuitable for this because of the presence of the Sultan von Banten. The company found a more suitable location in the city of Jayakarta at the mouth of the Ciliwung River. The city was under the influence of the Sultan von Banten, but the local ruler was weak and only a few thousand Sundanese colonized the city. In 1613 the VOC set up the first trading center in front of the city, which was expanded into a fort in the following years. There were some skirmishes with the EIC, the Sultan of Banten and the local ruler of Jayakarta in the following years. Dutch troops led by Jan Pieterszoon Coen ended the siege of the Dutch trading post in 1619 and destroyed Jayakarta in the process. On its ruins, Coen founded the Dutch city of Batavia , which became the seat of the Governor General, the supreme commander of the VOC in Asia and the so-called High Government ( Raad van Indië ). The latter included the highest-ranking representatives of the commercial staff, the military and the judiciary in Asia.

In 1621 the Dutch governor of Batavia, Coen, committed genocide to the people of the Banda Islands . About 15,000 people, almost all of the residents and all of the leaders, were killed. The aim was to create a monopoly for nutmeg on the island. Previously, the local population had refused and refused to agree to the monopoly. After the pogrom, the island was divided into parcels and these parcels were given to the Dutch as property. The new owners populated the island with slaves in order to build up a plantation economy for spices with them. The spices were sold to the VOC at a fixed price in return for the land that was given free of charge.

In the decades that followed, governorates emerged in Ambon, Banda, Makassar, Malacca, in Ternate for the Moluccas, Semarang for the north coast of Java, Negapatam for the Indian Coromandel coast, Colombo for Ceylon and, in the last phase of the VOC in the Cape Colony in the south Africa . The governors' administrative centers were similar to those in Batavia in that they also had a government, councils and their own garrison. Directors were hierarchically below the governors, concentrated on the commercial core business and had significantly reduced equipment and infrastructure compared to the governor's seats. For example, directors managed business in the Arabian Peninsula , the Persian Gulf , some central Indian offices and in Japan. The residences assigned to the governors and directors varied greatly in size. Some had a commercial staff and a military crew. Others consisted of just a single VOC envoy at the court of a local ruler.

The rise and heyday of the VOC

In 1641 the VOC conquered the Portuguese Malacca . In 1652 a VOC ship station was built at the Cape of Good Hope, and in 1659 Palembang on South Sumatra was conquered . In 1661 the VOC compelled Makassar on South Sulawesi to expel Portuguese from Malacca who had sought refuge in this city.

As the only trading company in India, the VOC made profits from overseas trade between 1635 and 1690. Thereafter, trade within Asia increasingly became the company's source of income until the 18th century. In addition, from 1639 there was trade with Japan, organized solely by the VOC. During the 17th century, the company also began secondary money transactions. The high profits made it possible to obtain gold , which was cheap in Asia (silver was very expensive, among other things due to the Chinese Ming government's change from a paper to a silver currency. Gold, on the other hand, was cheap for Europeans, compared to the relatively more expensive in China Silver can be exchanged) and resell at a profit - either directly in Europe or to European traders operating in Asia, who had to pay for textiles and spices, especially pepper .

In the late 1660s, the Banten government established a local rival association to the VOC, the Bantenese Company . The Bantenese Company soon took up direct trade with Mecca , Gujarat , the Coromandel Coast , Bengal, Siam , Cambodia , Vietnam , Taiwan and Japan and drew commercial agencies from England , the Netherlands, France, Denmark , Portugal ( Macau ) and the Empire of China ( Taiwan and Amoy ) to Banten. In the armed conflict between the former Bantamese regent Sultan Ageng and his son and successor Sultan Haji Abu Nasr Abdul Kahhar, the latter had to ask for the help of the VOC - and in return, after Ageng's surrender, expel all foreigners from Banten, and the VOC had a monopoly on the pepper trade and agree to the establishment of a VOC garrison, Fort Speelwijk. The economic and political importance of the Sultanate of Banten then waned until its dissolution at the beginning of the 19th century.

After the conquest of Makassar in 1667, the last port fell, from which trade between Asia and Europe could still be conducted outside the VOC, which from the VOC's point of view was considered smuggling. In 1699 the VOC in Java began to plant coffee from the Indian Malabar coast in plantations, which could now be traded alongside coffee from Arabia. There was also tea from China (see China trade ), textiles from India and others, as long as the goods promised to generate a profit.

Batavia as an Asian trading center

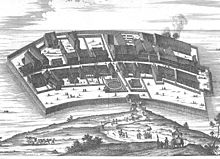

Batavia on Java developed into the center of the VOC in Asia. Large parts of the city were laid out according to plan. To the south of the market square, several canals provided drainage for the port city and a city wall surrounded the settlement. During the almost two centuries of the VOC's presence in Asia, central facilities such as a town hall, a central market square, several churches, hospitals, an orphanage and a large number of warehouses developed here. The fort developed into a walled, heavily armed fortress, which was surrounded by a moat. A ring of other small fortifications secured the area around the city. This made Batavia the location of the most powerful Dutch garrison in Asia, which temporarily housed a garrison of several thousand men. Shortly before the dissolution of the VOC towards the end of the 18th century, scientific facilities such as a botanical garden and a hydrographic institute were built here.

Batavia developed into the central trading center of the Malay Archipelago. Even if, for example, own fleets went from Ceylon to the Netherlands, Batavia was the central collection point for goods that were transported back to Europe once a year. Products brought back to Europe included spices and textiles from India, silk products from Persia, coffee from Arabia, metal goods from Japan and spices from the Malay Archipelago. Dutch merchants were not the only ones involved in delivering the goods. Since the expulsion of the Sundanese Jayakartas there has been a settlement ban for the Javanese majority, but numerous Asian ethnic groups have settled in the city. The majority of the population are Chinese, so that the historian Leonard Blussé describes Batavia as a Chinese colonial city despite the Dutch rule . The far-reaching ban on long-distance trade in the Chinese Empire had resulted in numerous Chinese merchants settling in Southeast Asian port cities. Some Chinese merchant dynasties from the coastal province of Fujian , who had one of the few Chinese licenses for overseas trade, were of particular importance to Batavia . From the port city of Amoy, today's Xiamen , they exported silk , porcelain , ceramics and, increasingly, tea to Batavia and were therefore essential supraregional inner-Asian suppliers for the VOC. In the environs of Batavia, sugar cane cultivation was dominated by Chinese entrepreneurs, mostly processed into arrack . In addition, there was regional trade along the north coast of Java in goods that were outside the commercial interests of the VOC. European privateers, on the other hand, supplied factories with basic foodstuffs and European luxury goods. Butter, olive oil, Bordeaux wines and genever can be found on the freight lists of private Dutch ships.

Goods exported to Europe

See also: India trade

Around 1620, pepper made up around 56 percent and other Moluccan spices around 17 percent of the goods transported to Europe by the Dutch VOC merchants. Around 1700 the proportion of pepper and other spices was 11 percent each. The consumption of spices in Europe had not decreased, but a demand for new products ensured a broadening of the range of imports and an increasingly different focus of the VOC. Textiles made up an increasingly large proportion of goods imported into Europe. In the middle of the 17th century their share was around 15 percent, at the turn of the 18th century it was 55 percent. Plantation products such as tea and coffee also became increasingly important. Coffee was cultivated by the VOC itself, especially in Java, while tea was initially bought in from China via supra-regional intra-Asian trade. However, when the demand for teenagers in Europe rose sharply in the course of the 18th century, the British East India Company dominated the tea trade from Asia for a while, as this East India Company bought its tea directly in Canton. From 1728 the directorate in Amsterdam established direct shipping between the canton and Amsterdam. From 1756 this business in Amsterdam was supervised by a special China commission. The trading station in Hugli in Bengal also transported his textiles directly to Amsterdam from 1734. Bengali fabrics sold best of all Indian fabrics in Europe. However, demand was also subject to fluctuations in fashion and the chamber was able to react more quickly with direct trade.

The intra-Asian trade of the VOC

The "High Government" in Batavia controlled part of the supra-regional intra-Asian trade, even if this took place in part without a turnover in Batavia. The major role that the VOC played in this trade was based on the one hand on controlling the spice trade in the Moluccas and on the exclusive position that the VOC held in the Japanese trade.

Since the middle of the 16th century there were mission projects of the Portuguese and Spaniards in Japan, which were supported by an increasingly intensive trade, but trade atrocities as well as the sometimes clumsy approach of the missionaries led to growing tensions with the Japanese rulers. An uprising of the predominantly Christian rural population in the Shimabara area, which was suppressed only with great difficulty, gave rise to the final expulsion of the Iberians and the ban on Christianity in Japan. Only the Dutch, who had had a branch in Hirado since 1609 , were allowed to stay in the country, but were relocated to Nagasaki in 1641. Their trading post was now on Deshima , an artificial island of around 13,000 square meters. The company had to pay an annual rent for this. Deshima had warehouses, houses and farm buildings, a garden and a modest cattle breeding facility to supply the European staff. Around 270 Japanese people worked on the island, 150 of whom were translators. Half a dozen VOC ships came in once a year with the summer monsoon. The sale took place according to established procedures through accredited intermediaries. Few Europeans had the opportunity to directly observe the country when the head ( opperhoofd ) of the branch set out on his annual trip to Edo to the Shogun's court , where he held a ceremony to thank the company for the approval of trade in Japan would have. Despite all the inconveniences and efforts, the VOC appreciated the exclusive market access. In Japan, raw silk and silk fabrics as well as cotton woven goods were mainly sold. In the absence of suitable export products, large quantities of precious metal initially flowed out of Japan, but the exports of copper, camphor, lacquerware and porcelain gradually increased.

The working conditions of the employees

In the almost 200 years in which the VOC existed, it is estimated that almost a million people traveled to Asia in their service. According to historians' calculations, of all these servants only about one in three returned. The others died of scurvy during the eight-month crossing to Batavia or afterwards of tropical diseases during their stay in Southeast Asia. The hygienic conditions on the ships were catastrophic by today's standards. 250 men were crammed together on the ships, which were only about 50 meters long, of whom the soldiers were only allowed to go to the upper deck for half an hour twice a day to get some fresh air. A saying in 18th century Germany was therefore: "Whoever beaten father and mother is still too good to go to East India." Many surviving Germans published travel reports in which they described the privations of their "tropical years", but also the charm of the exotic world. As a result, the VOC fell into such disrepute in the long run that the directors of the company ordered all employees to hand over any travel diaries to them upon arrival.

Downfall of the VOC

Corruption and a self-service mentality have prevailed within the company since it was founded, especially in the upper echelons of the individual trading branches, which is likely to have cost the Amsterdam and Middelburg parent company a large proportion of its profits. That is why the company signet VOC was translated as vergaan onder corruptie , downfall through corruption . The long distances, which from the Dutch point of view are unlawful areas of the East Indian areas, and the demands on the character profile of the management staff - in which, in addition to origin, primarily instinct for power or assertiveness, but hardly any honesty - favored this development.

The company's profit situation became critical due to changes in European customer requirements. Instead of spices, in which the VOC had a monopoly, other goods were now in demand. There was tough competition from the British East India Company, especially in tea, silk and china. Profits fell and were compounded by the foreign policy events. In the course of the 18th century, the assessable risks of overseas trade and thus also the administrative costs of the VOC rose to such an extent that ultimately losses were even incurred, which had to be covered by the company's financial reserves.

The company that undertook and not only survived the risky undertaking to navigate the English Channel during three wars with the British Empire, the first from 1652 to 1654 , the second from 1665 to 1667 and the third Anglo-Dutch naval war from 1672 to 1674 , but had meanwhile even developed into the largest trading company in the world, now began to suffer significantly from the fourth from 1780 to 1784 . The return fleets from Asia could no longer call at their European home ports, so there were no more goods auctions. In addition, the company, which was financially poorly equipped due to years of losses, now also lost its creditworthiness . The fate of the VOC was not sealed until the French invaded the Netherlands in 1795.

As early as 1791 they were forced to set up a committee of inquiry under the leadership of the inheritance holder, but without any significant successes being achieved. On September 12, 1795, the provisional people's representation formed after the revolution placed the company under state administration. In 1796 there was still a brief attempt to escape the link with the fate of the Netherlands and the intended nationalization by the Batavian Republic - the committee for affairs became the Comité tot de zaken van de Oost-Indische handel en bezittingen , the committee for affairs in connection with East Indian trade and possessions . The step with dubious prospects of success, which came too late, could no longer prevent the downfall of the VOC. On March 17, 1798, the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie , four years before its bicentenary, was dissolved. The bankrupt company was formally declared dissolved on December 31, 1799. Their remaining possessions became the property of the Batavian Republic and the debts were declared national debts.

In the final phase of the VOC, an infantry regiment from Württemberg , known as the Kapregiment , was used for military tasks by the VOC. Of the total of around 3,200 soldiers who marched off from Württemberg, only around 100 returned home.

The VOC archives

The archives of libraries in Jakarta, Colombo, Chennai, Cape Town and The Hague contain more than 25 million pages of documents on the activities of the VOC, which are collectively referred to as the VOC archives. In 2003, the archives were added to the UNESCO World Heritage List .

The VOC in Art and Literature

The majestic VOC ships were depicted by many contemporary Dutch painters, including Andries Beeckman, Abraham Storck and Adam Willaerts. Significant in literature is, among other things, a note in The Broken Jug by Heinrich von Kleist : “Go to East India; and from there, you know, only one of three men returns! ”In the form of a novel, the VOC was last taken up in“ Die Muskatprinzessin ”; here the life of the wife of Governor General Jan Pieterszoon Coen , Eva Ment , is described.

See also

- Dutch West India Company

- Dutch East Indies

- Dutch possessions in South Asia

- Eustachius de Lannoy , officer of the Dutch East India Company, who became an Indian general after his capture

literature

- G. Louisa Balk, Frans van Dijk, Diederick J. Kortlang: The Archives of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and the Local Institutions in Batavia (Jakarta). = De archieven van de Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC) en de locale instellingen te Batavia (Jakarta). Brill, Leiden u. a. 2007, ISBN 978-90-04-16365-2 .

- Hans Beelen: Trading with New Worlds. The United East India Company of the Netherlands 1602–1798 (= writings of the State Library Oldenburg. 37). Holzberg, Oldenburg 2002, ISBN 3-87358-399-2 (exhibition catalog of the Oldenburg State Library, October 17 - November 30, 2002).

- William Bernstein : A Splendid Exchange. How trade shaped the world. Atlantic Books, London 2009, ISBN 978-1-84354-803-4 .

- Roelof Bijlsma: De archieven van de compagnieën op Oost-Indie, 1594–1603. In: Verslagen omtrent 's Rijks Oude Archieven. Vol. 49, No. 1, 1926, ZDB -ID 449684-x , pp. 173-224.

- Ingrid G. Dillo: De nadagen van de Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie. 1783-1795. Schepen en zeevarenden. De Bataafsche Leeuw, Amsterdam 1992, ISBN 90-6707-296-6 (also: Leiden, University, dissertation, 1992).

- Christoph Driessen : The critical observers of the East India Company. The company of the “pepper sacks” as reflected in the Dutch press and travel literature of the 17th century (= Dortmund historical studies. Vol. 14). Brockmeyer University Press, Bochum 1996, ISBN 3-8196-0415-4 .

- Femme S. Gaastra: The United East India Company of the Netherlands - an outline of its history. In: Eberhard Schmitt, Thomas Schleich, Thomas Beck (eds.): Merchants as colonial masters. The trading world of the Dutch from the Cape of Good Hope to Nagasaki 1600–1800 (= publications of the Bamberg University Library. Vol. 6). Buchner, Bamberg 1988, ISBN 3-7661-4565-7 , pp. 1-89.

- Femme S. Gaastra: The Dutch East India Company. Expansion and Decline. Walburg Pers, Zutphen 2003, ISBN 90-5730-241-1 .

- Femme S. Gaastra: De geschiedenis van de VOC. Fibula-Van Dishoeck et al. a., Haarlem et al. a. 1982, ISBN 90-228-3838-2 (also: numerous editions and editions).

- Roelof van Gelder: Het Oost-Indisch avontuur. Duitsers in dienst van de VOC (1600–1800). SUN, Nijmegen 1997, ISBN 90-6168-492-7 (also: Amsterdam, University, dissertation, 1997).

- In German: The East Indian Adventure. Germans in the service of the United East India Company of the Netherlands (VOC), 1600–1800 (= writings of the German Maritime Museum. Vol. 61). From the Dutch by Stefan Häring. Edited by Albrecht Sauer and Erik Hoops. Convent, Hamburg 2004, ISBN 3-934613-57-8 .

- Hans de Haan: Moedernegotie en grote vaart. A study on the expansie of the Hollandse commercial capital in de 16e en 17e eeuw. SUA, Amsterdam 1977, ISBN 90-6222-027-4 .

- John Landwehr: VOC. A bibliography of publications relating to the dutch East India Company 1602-1800. HES, Utrecht 1991, ISBN 90-6194-497-X .

- Jürgen G. Nagel : The adventure of long-distance trading. The East India Companies. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2007, ISBN 978-3-534-18527-6 .

- Robert Parthesius: Dutch Ships in Tropical Waters. The Development of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) Shipping Network in Asia 1595-1660. Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam 2010, ISBN 978-90-5356-517-9 (also: Amsterdam, University, dissertation, 2007; online ).

- Eberhard Schmitt, Thomas Schleich, Thomas Beck (eds.): Merchants as colonial masters. The trading world of the Dutch from the Cape of Good Hope to Nagasaki 1600–1800 (= publications of the Bamberg University Library. Vol. 6). Buchner, Bamberg 1988, ISBN 3-7661-4565-7 (exhibition catalog, Bamberg, October 9 - November 30, 1988).

- Daron Acemoglu , James A. Robinson: Why Nations Fail. The origins of power, wealth and poverty. S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2013, ISBN 978-3-10-000546-5 .

Web links

- De vocsite : Extensive web content on the VOC (Dutch)

- Femme S. Gaastra: VOC Organization. TANA

- Douglas A. Irwin: Mercantilism as Strategic Trade Policy: The Anglo Dutch Rivalry for the East India Trade. The Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 99, No. 6, December 1991, pp. 1296–1314 (PDF file; 1.91 MB, English)

- Oldest share - the oldest known share (Andeel) in the world: VOC 1606

- VOC knowledge center of the Netherlands Institute for Linguistics, Agriculture and Folklore, Department of the Royal Academy of Sciences (Dutch)

- kriegsreisen.de: The magic of East India. The colonial service in the VOC.

- Entry of the VOC archive into the UNESCO World Document Heritage .

Single receipts

- ↑ Nagel, p. 100

- ^ A b William Bernstein: A Splendid Exchange - How Trade Shaped the World , Atlantic Books, London 2009. ISBN 978-1-84354-803-4 . Pp. 218-221. (engl.)

- ↑ a b Nagel, p. 101.

- ↑ a b Nagel, p. 102.

- ↑ Nagel, pp. 101f.

- ↑ Nagel, p. 40f.

- ↑ Horst Lademacher : History of the Netherlands. Politics - Constitution - Economy. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1983, ISBN 3-534-07082-8 , p. 142.

- ↑ a b Nagel, p. 41.

- ↑ Nagel, p. 103.

- ↑ Nagel, pp. 103f.

- ↑ Nagel, p. 104.

- ↑ Giles Milton: Nutmeg and Muskets. Europe's race to the East Indies . Zsolnay, Vienna 2001, ISBN 3-552-05151-1 , p. 313.

- ↑ Nagel, p. 44f.

- ↑ Nagel, p. 74.

- ↑ Nagel, pp. 74f.

- ↑ a b Nagel, p. 50.

- ^ Jochen Pioch: Merchants and Warriors. In: GEO EPOCHE No. 62. G + J Medien GmbH, accessed on June 24, 2020 .

- ↑ Daron Acemoğlu, James A. Robinson: Why Nations Fail. P. 303.

- ↑ Nagel, p. 51.

- ↑ Nagel, p. 113.

- ↑ Nagel, p. 116.

- ^ Leonard Blussé: Batavia, 1619-1740. The Rise and Fall of a Chinese Colonial Town , in Hlurnal of Southeast Asian Studies. 12/1981, pp. 159-178.

- ↑ Nagel, p. 115.

- ↑ a b Nagel, p. 117.

- ↑ Nagel, pp. 118f.

- ↑ Nagel, p. 63.

- ↑ Nagel, p. 66.

- ↑ Nagel, p. 111.

- ^ Rise and Fall of the Dutch East India Company. Nagasaki City, accessed August 6, 2010 .

- ↑ Christoph Driessen: A short history of Amsterdam. Regensburg 2009. p. 38.

- ↑ Christoph Driessen: A short history of Amsterdam. Regensburg 2010. p. 72

- ↑ Driessen: Netherlands, p. 73.

- ↑ Driessen: Netherlands, p. 72

- ↑ Roelof van Gelder: The East Indian Adventure. Germans in the service of the United East India Company of the Netherlands (VOC) 1600-1800. Writings of the German Maritime Museum.

- ↑ Christoph Driessen: The critical observers of the East India Company. The company of “pepper sacks” as reflected in the Dutch press and travel literature of the 17th century. Bochum 1996. p. 149.

- ↑ Carl Jung: Kaross and Kimono. P. 36. ISBN 978-3-515-08120-7 , from Google Books , accessed December 30, 2011.

- ↑ Hic et Nunc - www.hicetnunc.nl - [email protected]: TANAP - About / An ambitious world of heritage. Retrieved on August 26, 2017 .

- ^ Archives of the Dutch East India Company | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Retrieved on August 26, 2017 .

- ↑ George S. Keys: Mirror of Empire, Dutch Maritine Art of the Seventeenth Century, The Hague 1990

- ↑ Christoph Driessen : The Muscat Princess, Langwedel 2020