Cape Regiment

Kapregiment is the common name of the Württemberg Infantry Regiment . From 1787 to 1808 it was in the service of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). Other names were Kaper Regiment and Indian Regiment . Of the 3,200 soldiers who marched off from Württemberg, only 100 returned.

background

Political events in Europe

The political development in Europe also had an impact on the overseas possessions of the states involved in the individual conflicts and thus directly on the fate of the regiment in Africa and India.

- 1787 march of the regiment into the territories of the VOC

- 1789 French Revolution

- 1792 First coalition war until 1797, as a result, on February 1, 1793, France declared war on the United Netherlands

- 1795 proclamation of the Batavian Republic , Great Britain occupies the Dutch colonies (June 11 British warships in False Bay, August 3rd British warships off Trincomalee)

- 1798 Dissolution of the VOC and transfer of its territories to Holland

- 1799 Second coalition war until 1802

- March 27, 1802 Peace of Amiens , as a result the UK returns the Cape of Good Hope to Holland in 1803

- 1805 Third coalition war

- January 1, 1806 Württemberg becomes a kingdom

- January 8, 1806 The Cape becomes a British colony for good

- March 1, 1808 Dissolution of the regiment

Currencies

In order to understand the amounts of money mentioned again and again and their value, the currencies common at the time are briefly presented here. A precise comparison of the monetary value at that time with today or a conversion into euros is not possible; a comparison of the prices for goods and services only allows an approximate comparison due to their different importance at different times.

Regardless of the various currencies in circulation, the Reichstaler was the currency and unit of account in the German Empire and the Rixdaler (Rijkdaalder) in Holland. However, this was only important for a few wealthy people and merchants, normal people only knew and reckoned with the smaller coins , at best gulden, in Württemberg mostly with Batzen = 2 half Batzen = 4 Kreuzer = 16 pfennigs = 32 Heller .

At the end of the 18th century the values in Europe were:

-

1 Reichstaler = 1 ½ fl. (Gulden) = 90 xr (kr., Kreuzer) = 240 dl. (Pennies)

- 1 guilder = 60 kreuzers (= 20 stuivers)

- 1 chunk = 4 cruisers

- 1 kreuzer = 4 pfennigs

- 1 pfennig = 2 hellers

In the Netherlands was

- 1 Rixdaler = 1 Ducaton = 3 Dutch guilders = 2 ½ guilders = 60 stuiver ( Stüber )

- (corresponds to 150 cruisers in Württemberg)

At the Cape of Good Hope and on the Indian Islands, however, the VOC (“valeur de'l Inde”) applied around 1790

- 1 Kaprixdaler = 3 Cape guilders = 2 Dutch guilders = 48 (VOC) stuivers

- 1 Ducaton = 72 (VOC) students

- 1 cape guilder = 16 (VOC) stuivers

- 1 (VOC) Stuiver = 8 (VOC) Duit

For the regiment, however, the stipulation in Article 9 of the subsidy contract applied: "les Rixdalers à Soisante quatre Stüvers". This course was valid for accounts of the regiment itself ( regimental treasury ) with the VOC as well as for its relatives. Because of the dangers of the sea route, money was transferred from the colonies to Europe not by transporting coins, but cashless by paying into the VOC cash register (= credit to an account) overseas and withdrawing the credit from the VOC cash register in Europe.

The course brought two disadvantages for the recruits, which they were not aware of at the conclusion of their surrender (or, as far as individual officers perhaps knew parts of the contract, were not clear). On the one hand, this meant that the members of the regiment only got 1 Rixdaler (or 2 ½ guilders) for 64 Stüver instead of 60, i.e. a loss of 6.6%. With the “valeur de l'Inde” payment, they also received valid money only in the colonies (Kaprixdaler, Kapgulden, VOC-Stuiver). For 1 gulden pay paid out in cash at the Cape , they could pay in 16 VOC students there. In order to get 1 gulden paid out in Europe, they had to pay in 20 VOC students ("... 270 gulden. If these were in the company coffers [= VOC treasury] left, the bill would be assigned to Europe at the end of the year and paid there with 270 guilders in Dutch or 5400 stuers. But now the regiment must take these on the cap, the Rixdaler at 64 stuers, does 4050 stuers. This money is in on the cap is paid at 48 stüber coursing Rixdalers, or according to this same ratio in ducatons at 72 stüber. And the company does not take these same ducatons into its coffers for payment in Europe more than 67 stuers; and therefore pays 4050 stuers instead of 4050, in Holland only 3766 stüber, or instead of 270 guilders only 188 guilders 6 stüber. ")

In Java, payment was made in inferior copper money. According to a report by Magister Spöhnlein, the value of the paid fee of 100 florins was actually still 38 Dutch or 36 Württemberg guilders.

Subsidy contract

On October 1, 1786 joined Duke Karl Eugen (Württemberg) with the Dutch East India Company a surrender agreement (commitment period) on the position of infantry - regiment and an artillery - company for deployment on the Cape of Good Hope . The contract negotiations had started in 1784 through an initiative of the Wuerttemberg captain and war commissioner Ludwig Friedrich von Knecht, who was in the service of the VOC. In doing so, the Württemberg negotiators overlooked the political and financial situation of the VOC, which was already in decline at that time.

The most important contractual points were on the one hand the target level of the regiment with structure, precise determination of number, ranks and pay of the personnel as well as the armament and uniforms and on the other hand the payment obligations of the VOC.After that, the regiment should consist of two battalions with five companies each (four fusilier companies and one grenadier each - or a Jäger company) and an artillery company with a strength of 58 officers , 170 NCOs and 1,751 men . The VOC committed itself to a one-off payment of 300,000 florins (“Florins argent d'Hollandaise”, for the currencies see paragraph above) to the duke for the installation and initial equipment of the regiment and 72,000 florins for the transport to Vlissingen as well as 65,000 florins annually thereafter for the replacement of the expected losses (according to a contract signed on November 13, 1797, this sum was only 35,000 florins a year from 1797). The owners of the companies were to receive 45 fl. (Fusilier companies) or 55 fl. (Grenadier, hunter, artillery company) a month for the maintenance of weapons and equipment. In relation to the soldiers , she only undertook to pay the fees to the officers and the wages to the NCOs and men (and to provide the services specified in the Dutch certificate of surrender).

Although negotiations took two years, the contract had many disadvantages for the duke or the recruited, also because the Württemberg negotiators were not familiar with the customs in the colonies and the negotiators of the VOC in their own interest did not point this out or fail to provide necessary regulations entered into the contract. So it contained u. a.

- no time limit (Prince p. 14: "The company had been careful not to conclude the contract for a certain number of years only. The reason for this was that it was very frankly informed by its negotiators that it did not wish to deal with the costs to be charged for any necessary repatriation of the regiment. ");

- the right of termination only for the VOC;

- the right of the VOC to use the regiment wherever they see fit. This part of the contract was kept secret from the regiment by both contracting parties until 1791. Thus the Duke - only nominally owner of the regiment - had no influence on its further use after the regiment was handed over. Several protests / petitions from officers to the Duke from 1791 onwards were unsuccessful.

- the reservation that only the VOC may supply material to replace the fittings. However, since no quality or price information was stipulated in the contract, she took advantage of this in the following years by lowering the quality of the goods and / or excessive prices (which also had to be paid in Holland with Rixdalers at 64 stuivers, while the regiment only paid Rixdalers 48 stuivers took). The respective regiment and company owners therefore never achieved the expected income.

- the stipulation that the fees and wages would be paid in "Indian currency", which the recruited was not aware of. The effects are described in more detail in the Currency section above .

After the conclusion of the contract, in November 1787, Captain von Penasse became the duke's permanent representative to the Chamber of VOC in Middelburg as the military charge d'affaires . His tasks included further negotiations with the VOC on all further questions.

After Duke Friedrich Eugen learned of the occupation of the Cape of Good Hope by Great Britain in early 1796 , he planned to give the regiment in British subsidies and at the same time to achieve an increase in the annual payment to 100,000 Fl. The chief steward of the Hereditary Prince Friedrich , Karl von Zeppelin , who was already in London , started negotiations. But they failed because of the rejection of the offer by the British court.

Advertising the regiment

There was only six months available for the formation of the regiment. After the advertising contract concluded with the former Grenadier - Captain von Langsdorff on October 21, 1786, Langsdorff undertook to recruit the required number of soldiers and deliver them to Ludwigsburg . He was able to hire more recruiting officers, and he was also given a command of twenty NCOs and teams from the Württemberg military to transport the recruited. He received 36 florins for each recruited man. In addition, he was given the character of a sergeant- major.

Advertising was not only carried out in the Duchy of Württemberg, but also in the neighboring smaller lordships and imperial cities as far as Frankfurt a. M. The bonus money was - depending on the size and suitability of the person recruited - 16 to 36 florins. The promised pay of 9 or 9½ florins per month was compared to other incomes at the time (e.g. received a württembergischer day laborers 12 kr ( Kreuzer ) = 1 / 5 fl. per day, a servant of 30-40 fl. in) high, so that the recovery of the teams initially made no difficulty, nachhalf especially since the authorities with a slight coercion to unwanted To get rid of people (However, the recruited did not know that the wages would be paid in Dutch guilders, the value of which was around 25% lower than the guilders in the empire ). Before the 1st Battalion marched off, the Duke personally released those who had stood up; anyone who did not want to go to Africa could leave the regiment immediately. However, only a few did so.

The officers and non-commissioned officers came from existing Württemberg regiments, with the officers having to pay the duke between 700 and 1,000 florins to get a job. The latter also used the opportunity to send unpleasant officers out of the country. He also “looked after” six of his illegitimate sons (Lieutenant Colonel Count Wilhelm von Franquemont, Lieutenant Karl David von Franquemont (v. Franquemont I), Friedrich von Franquemont (v. Franquemont II), Karl von Franquemont (v. Franquemont III), Grenadier Captain (1791 Major) Karl von Ostheim, first lieutenant (later captain lieutenant) Karl Alexander von Ostheim).

The commitment period ( surrender time ) was at least five years from the first day of arrival on the Cape of Good Hope. A further obligation with an increase in pay was possible.

- For by

keeping the measurement [measure size]

which, against an acknowledgment hand money under

the Herzoglich-Württemberg - Dutch East Indian-for services of

certain Compagnie Infantry Regiment, at the time of six years,

going from

up such has Let it be advertised that

during his period of service he paid him nine guilders a month in Dutch for

his pay - and that he would not only benefit from this company, which was intended for the troops, in

terms of food,

lodging, and other benefits like to enjoy, but

also when he

wants to return to his home after his capitultion, is transported and fed back to Holland free of charge and free of charge, and on

his arrival there a gratuity of

one hundred gulden Dutch from the Ostindisch-Hlooländischen Compagnie

should receive cash paid.

If, however

, he should have the urge to capitulate with the regiment , he is promised a proportionate

increase in wages with every renewal of capitulation, subject to all the advantages that will be granted to him upon

his departure, as stated above.

Documented this capitulation note, made out to the highest order of His ducal

highness ihme - under my handwritten signature

.

Sr. Ducal Highness

of Würtemberg "

In Vlissingen everyone had to sign again, although the VOC only recognized this surrender. Very few could understand the Dutch text.

- Is heeden zoom in to Krygsdienst of the Nederlandsche Goectroieerde

Oost-Indische Compagnie. as a fuselier, om dezelve

Compagnie den tyd vam vyf Jaaren te serve in India,

nietende duurende dien dienst neegen Gulden's Maands, be

halven nog het gewoon randcoen en kostgeld, voort een vry

tarnsport naar, en uit India, en onerhoud aan bord,

benevens een geheel vrye uytrustung, en na uytgedient association

in India by te rugkomst here te country, boven all een

gratificatie van Honderd Guldens.

Deeze Acte van Capitilatie geeft van het een different vol-

ume verzeekering. "

Officers could quit their duties at any time with the approval of the regimental commander and the respective garrison commander, which many made use of over the years. They were replaced by promotions from the regiment. The officers could also go on “home leave”, but the journeys at their own expense and without a fee during the entire absence.

Up until 1794, replacement crews were repeatedly forwarded. This was initially done from Württemberg, but as the transport to Holland was too expensive for the Duke and many deserted on the march, an advertising center was set up in Middelburg from 1790 under Major von Penasse as the Duke's permanent representative in Holland . A total of around 1,200 men were forwarded by 1795.

In 1792 the first capitulation (commitment period) expired. Most of them signed up for a bonus of twelve Dutch Rixdalers and higher wages for another five years and again later, since they saw no possibility of returning home. (The VOC had promised free return transport, but preferred to carry paying passengers on its ships, so that those who passed had to wait for months without income for a lift.)

The regiment

There is no such thing as an “official installation date” for the regiment. At the beginning of November 1786 the commander, the officers of the staff of the 1st Battalion and the first regimental quartermaster (responsible for the treasury) began their duties, the recruits gradually arrived. After its formation in Ludwigsburg, the 1st Battalion was sworn in on May 2nd and the 2nd Battalion on October 26th, 1787 in Vlissingen. The regiment owner remained nominally the ruling Duke of Württemberg all the time, but neither Carl Eugen nor his successor, to whom the respective regimental commander regularly sent reports (as far as the political situation allowed shipping to the mainland in Europe), continued to look after the regiment.

The regiment was officially disbanded on March 1, 1808 by order of the Dutch Governor General in the Dutch East Indies, General Herman Willem Daendels , the remaining 229 men, including the officers, who were still alive, were integrated into the Dutch troops there despite their protests.

Strength and structure

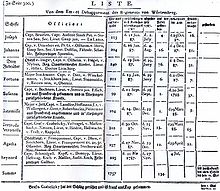

The regiment was divided into two battalions and one artillery - company . The following list shows the structure in 1787 when the regiment was handed over to the Dutch East India Company, with the names in brackets behind.

The regimental staff consisted of the staff officers

- 1 Colonel and regimental commander (Theobald von Hügel, † June 30, 1800), also commander of the 1st battalion

- Successor:

- There was no official successor appointed by the Duke. After the death of Hügels, Franz Karl Philipp von Winckelmann, who was temporarily promoted to major in 1798, assumed nominal command of the parts of the regiment on Ceylon as the highest ranked officer in India while still in captivity (Major Vellnagel had died in captivity in Madras on April 21, 1796) In the autumn of 1806 he took command of the rest of the regiment on Java.

- 1 lieutenant colonel (Friedrich Wilhelm von Franquemont, † December 13, 1790 in Cape Town), at the same time commander of the 2nd battalion

- Successor:

- * 1791–1791 Lieutenant Colonel Maximilian von Jett († October 19, 1791 in Batavia)

- * 1791–1792 Lieutenant Colonel Karl von Ostheim (entered Dutch service in Batavia in November 1792, † February 20, 1793 in Batavia)

- * 1792–1807 Lieutenant Colonel Johann David Gottlieb von Schmidgall († January 5, 1807 in Samarang)

- * 1807–1808 Lieutenant Colonel Franz Karl Philipp von Winckelmann (entered regular Dutch service in 1808)

- 2 majors (Premier Major Maximilian von Jett, 1st Battalion, and Seconde Major Isaak von Stackmann, 2nd Battalion)

- 1 Secretair du Colonel ( Second Lieutenant Heinrich Dollfuss)

and the staffs of the two battalions.

The 1st Battalion with an initial strength of 32 officers, 78 NCOs and 962 men consisted of

Great staff

- Adjutant ( Premier-Lieutenant Johann Christoph Friedrich von Hügel)

- first regimental quartermaster (Captain Gottlieb Binder, returned)

- first auditor (Captain Ernst Friedrich Steeb)

- Regimental priest (Magister Johann Friedrich Spoenlin, returned to Württemberg in 1792 "because of illness")

- Surgery major (Dr. Friedrich Ludwig Liesching, resigned in 1795 and stayed in South Africa)

Small staff

- 2 Porte Enseigne ( Ensigns of Obernitz, Schaiblin)

- 2 field preachers

- 1 drum major

- 1 Profoss

- 6 Hautboists (musicians)

- 1 rifle handle (weapon master)

a company of grenadiers (Captain Karl von Ostheim) and

four companies of fusiliers

- Colonel Company ( Staff Captain Johann Michael Beurlin)

- Majors Company (Staff Captain Gottlieb August Döbener)

- Uttenhouven Company ( Captain Christoph Wilhelm von Uttenhouven)

- Diez Company (Captain Franz Anton von Diez)

The II. Battalion with an initial strength of 28 officers, 92 NCOs and 972 men consisted of

Great staff

- Adjutant (Premier-Lieutenant Gottfried Eberhard Hoffmann)

- second regimental quartermaster (Lieutenant Christoph Wilhelm Stecherwald, † August 18, 1792 in Batavia)

- second auditor (Lieutenant Friedrich Gottlob Koch)

- Field preacher (Johann Gottlieb Gartbach)

- second regiment archer (Johann Gottlieb Poeselt)

Small staff

- 2 Porte Enseigne (Ensigns Charles, David)

- 1 drum major

- 1 Profoss

- 3 Hautboists (musicians)

- 1 rifle handle (weapon master)

a company of hunters (from Dhen) and

four companies of fusiliers

- Lieutenant Colonel Company (Staff Captain Franz Carl von Stockhorn)

- Majors Company (Staff Captain Carl Joseph von Landsee)

- Company Czabelizki (Captain Johann Carl Wenzeslaus Graf von Czabelizki)

- Vellnagel Company (Captain Vellnagel)

The artillery company (Captain Johann Daniel von Schmidgall) carried four seven-pounder howitzers , four three- pounder cannons and four six-pounder cannons and had an initial strength of 6 officers, 19 NCOs and 161 men. According to the original plans of the VOC, the company should form the basis for a “genius and artillery school” on the Cape. However, that did not happen.

The strengths (NCOs and men) of the companies when marching out of Ludwigsburg are shown in the table opposite. The division of officers (apart from those mentioned above) among the companies can no longer be assigned from the documents.

Until the regiment was dissolved, many changes were made to the officers and non-commissioned officers. Relocations were made by the regimental commander, as were the promotions of NCOs and men. The regimental commander had the promotions of the officers confirmed by the respective governor of the VOC and then announced them provisionally . The final officer's license then had to be confirmed by the Württemberg War Council or the Duke of Württemberg, which often took months with the insecure postal (ship) connections.

Armament and equipment

The armament was precisely regulated in Article 8 of the Subsidy Treaty. The fusiliers were armed with muskets with bayonets , the hunters with rifles and sabers , and all of them carried cartridge pouches on straps over their shoulders. The officers and sergeants carried swords . The firearms were procured from Suhl , the remaining first armament and equipment were manufactured in the duchy.

The other equipment of the regiment (Article 18 of the Subsidienvertrages : Ustensiles de Campagne ) was provided by the VOC.

Some of the uniforms and equipment were already unusable on the transport to the Cape of Good Hope.

If it was still possible to maintain or supplement the armament and equipment to a reasonable extent during the stay on the Cape of Good Hope (only 45 fl. (Fusilier companies) or 55 fl. (Grenadier, hunter , Artillery company) available), this was no longer possible on the rear Indian islands.

Valve list….

March 22, 1794, along with the company, was taken over by Lieutenant Beurlin, who was in command of the company ad interim at the time, 123 rifles, 129 sabers, 129 cups, 123 cartridge pouches, 125 caquets, 2 drums

During the two expeditions to Banda and Ternate, casquets and leather goods were completely lost and broken, 20 rifles, 32 sabers, 109 cupels, 59 cartridge pouches, 125 casquets, 1 drum fell apart

83 rifles, 93 sabers, 44 cartridge pouches, 1 drum have been handed over to the local arsenal

In use by the company and currently 10 rifles, 2 sabers, 20 cartridge pouches and 20 Cuppels "

The armament and equipment got more and more into a hardly usable condition, especially since the VOC only tried to reduce the expenses for the regiment.

Regimental economy

Colonel von Hügel was no different from other regimental commanders of his time. The distance to Württemberg and the resulting lack of control by the administration made it easier - and sometimes even forced - the amalgamation of personal business with those of the regiment. Hügel claimed the regiment's right to run wine taverns, baker's, butcher's, tailor's and shoemaker's shops for himself and supplied the regiment from these shops, of course at a profit. He was then later accused of having “initially taken care of the regimental administration assigned to him as commandant for himself, but only for the regiment insofar as he had confronted him as a seller and thereby transformed his official position into a more commercial one. “He also engaged the First Regimental Quartermaster Binder, after Johann Martin Canzleiter's departure from the regiment in 1792 (see individual fates), in his private business. The amalgamation was also the reason for the process of withheld pay shown below.

uniform

The uniform corresponded to the European uniforms of that time. So it was perhaps still suitable for South Africa, but by no means for service in the tropics. In accordance with the customs of the time (company economy), it was to be paid by the obligated persons themselves; the non-commissioned officers and men were deducted this in installments from their wages. The soldiers therefore arrived at the Cape with debts.

The soldiers wore a blue cloth skirt with red lap envelopes, a yellow collar, yellow discounts , lapels and armpit flaps , a white waistcoat, a black collar, white trousers, black cloth gaiters and buckled shoes, and a casket as headgear . This was made of leather with a shield made of tinned brass (officers silver), a black (for officers white), hanging down horsehair comb and a yellow-blue plume on the left side. On the upper part of the shield was the Dutch coat of arms, on the lower the Württemberg coat of arms, on the humps on the sides of the casket the name of the duke (grenadiers grenades). The price of a kit was around 50 fl (see also the list below in the section March to Holland : Costs of the March ). The soldiers also had the braid that was customary at the time.

In Vlissingen, every man and sergeant received a ship's clothing (“Camisol with white cloth, 1 white cloth trousers, 1 fine linen underpants, 1 Roquelaur, 1 Pr Matelotte pants made of gray canvas, 2 blue shirts, 1 Trilchener Lapp, 1 twin Camisol with sleeves and collars, 1 pr of the same English trousers, 1 pr of filthy stockings "for the price of 22 fl. 1 1 ⁄ 2 kr), which were deducted from the pay (see also below the list in the paragraph March to Holland : ship's outfit ). The other pieces of uniform had to be packed and were not allowed to be worn during the crossing to Cape Town without special permission. Most of the packaged clothing and equipment arrived in Africa after the long sea voyage, rotten and unusable, and had to be replaced (at the expense of the soldiers).

Flags

Each battalion received two different flags: one from Württemberg with a yellow base color and one made of white taffeta with the Dutch coat of arms on one side and the intertwined initials of the VOC on the other.

Pay and fee

The payment of the officers (salary) and the NCOs and men ( salary ) was precisely regulated in the subsidy contract for each position (in the following, salary always also means salary).

The adjacent table shows the amount of the wages in Dutch guilders for the individual ranks. Two thirds of the wages on the Cape were paid out in paper money or Cape guilders that only circulated on the Cape and had no value as cash in Europe.

The actual payout was never made in full. A third was always kept with the regiment to pay for the uniform and food. What did not need the individual from the rest, he could at the box office of the regiment or the company leave . Over the years, this resulted in a savings balance that was paid out to him at the end of the commitment period. The Dutch troops and the other subsidiary troops in Dutch service were able to leave these amounts at the cash register of the VOC in Holland . The VOC refused to do the same with the members of the regiment, as this was not provided for in the contract. So they had to have all the money in the colonies paid out by the regiment, they had to pay any savings in the colonies into the VOC's coffers and received less in value in Holland in return, as shown above. The VOC only permitted once a four-month salary to be withdrawn in Holland for four years. This was ultimately the reason for the process described below.

Other supplies

The officers had to provide for board and lodging at their own expense.

The soldiers had to pay everything from their wages except for accommodation. At that time they were usually given new clothes every two years, but in this regiment every year because of the heavier use in the tropics.

For the sick and wounded, the regiment set up a private hospital (on the cape hospital one). During their stay there, the soldiers received free food, but no pay.

The heirs were entitled to the wages that had accrued up to the day of death and had not yet been paid out (see also the section The process of withheld wages below ), and the duke received the wages to be paid by the VOC for three months according to the contract after deduction of the funeral costs.

Use of the regiment

March to Holland

The 1st Battalion, led by the regimental commander, marched out of Ludwigsburg on February 27, 1787 with around 950 men and reached Dunkirk on April 4. The march through France was by King Louis XVI. allowed by France (against payment of 5,000 florins). The main problems during the march were the provision of food, the wear and tear of the bad shoes and their replacement (see below note a) Fee from the march through France ) and the desertions . The battalion marched over Vaihingen an der Enz - February 28th Dürrmenz - March 1st rest day - March 2nd after 6 hours Söllingen - March 3rd after hours Ettlingen - March 4th after 6 hours Iffezheim - March 5th Fort Louis ( “Weather quite rainy ... In order to prevent desertion, the field guards were strengthened, lower and upper officers, especially the Colonel, rode around the whole night, and this great vigilance overtook many who wanted to desert without this extreme care the desertion was terribly large, which could not be prevented entirely ” - March 6th after 5 hours in Hagenau (rain) - March 7th after 4 hours in Hochfelden (rain) - March 8th after 5 hours in Pfalzburg (rain,“ Through the 7-day march without a day of rest, because of bad shoes , in which people ran out of water, and because of the bad weather so many sick people that 50 of them had to be left in the hospital in Pfalzburg ”- March 9 rest day - March 10 after 4 hours Saarburg - March 11th after 5 hours Maizières - March 12th after 5 hours Vic - March 13th rest day - March 14th 5 hours Juville - March 15th 5 hours Metz ( "shoes for soldiers provided" - March 16th after 6th Hours Conflans - March 17th after 4 hours Etain - March 18th rest day - March 19th after 5 hours Damvillers - March 20th after 7 hours Stenay - March 21st 7 hours Sedan - March 22nd 5 hours Mezières - March 23rd rest day - March 24th Maubert - March 26th La Capelle - March 27th after 8 hours Le Cateau-Cambrésis - March 28th rest day - March 29th after 5 hours Cambrai - March 30th Douai - March 31st after 8 hours Lille to Dunkirk . On April 12th, the teams were transported from there by ship to Vlissingen , and Colonel von Hügel with his staff followed them by land on April 17th. The food in Holland was so good compared to the march that it was specially mentioned: “In the morning everyone gets a glass of brandy and bread, at noon barley, rice or beans, and a good portion of meat, in the evening butter, cheese, bread and beer. "

liable debts and their payment

I) Fee from the march through France

- In Pfalzburg for shoe soles

- Leather and stain 441 pounds

- Shoe soles including maker's wages 240 fl

- 2 bags 2 fl 14 s (Stuiver)

- 241 fl 14 p

- In Metz for

- 250 pr new shoes, of which each company

- 50 pr receive 3 fl 5 s 812 fl 10 s

- 5 bags of 2 10 fl

- 822 fl 10 s

- To Lille

- Shoe soles and leather

- 183 fl 12 p

II) Ship assembly

- From the embarrassed team, on which only 3rd month advance payments were made,

- specified according to the annex

- 19,452 fl

III) Of small pieces of equipment sold

- The verified system proves the wear

- 567. Shirt according to the price on the Cap à 50 Stuvers 1417 fl 10

- 1156. pr white linen stocking of 36 pieces 2080 fl 16 s

- 702 pr shoes of 48 pcs

- 1684 fl 16 p

- A total of 29,984 florins

After sick stragglers had arrived and all of them had been examined (for three days) by a VOC doctor, the battalion was sworn in to the Dutch East India Company on May 2, with a strength of 891 men (without officers). Because of the sick, the duke was paid for only 871 men.

The 2nd battalion and the artillery company marched on September 2, 1787 under the leadership of Lieutenant Colonel von Franquemont in Ludwigsburg, reached Dunkirk on October 6 and Vlissingen on October 8. After the guns and the heavy baggage had arrived (they were transported on the Rhine), the battalion was sworn in and handed over to the Dutch East India Company on October 26th.

Since losses on the march were normal for all troops at this time , they are shown in more detail here. A total of 215 men (including 1 premier sergeant and 9 corporals) deserted on the march, 21 died and 27 sick people were left behind on the way. In addition, there were 118 sick people on arrival in Vlissingen. In addition, 7 were sent back to Ludwigsburg. However, 12 men forwarded from Ludwigsburg and 13 newly recruited on the march were added. In total, the VOC took on 196 fewer people than agreed (and paid correspondingly fewer).

In Holland everyone received an advance payment for three months, but the NCOs and crews were immediately deducted most of it for their gear. Most of them arrived with debts at the regiment in Africa, which was offset against the pay due there.

Crossing

In Vlissingen and Rammekens, the troops were embarked (embarqued) in nine ships which, depending on the weather, only sailed later on different dates. The officers had to organize and pay for their own food for the crossing.

Days, sometimes weeks, passed between embarrassment and the actual departure, during which the soldiers had to live in the cramped quarters of the ship. The crossing itself usually lasted over four months, with “Gatemisse” sailing the fastest with 98 days, and “Reynord” taking the longest with 220 days. With the cramped accommodation and insufficient food, illnesses were not absent. A report from the first half of the century describes the situation: “The so-called space between the decks, where these people eat and sleep, lacks fresh air. The vapors of so many sleeping people lying next to and next to each other, the crudidates in those stomachs that are unaccustomed to the ship's food, which go into putrefaction, the frequently stinking - or, what is worse, acidic water, cause diseases only too quickly ... when they come to the promontory of Good Hope, look, according to the color of their face, more like a dead person than a living person. ”137 men died on the crossing to Africa, 262 arrived sick, 120 of whom died in the first two months . Exceptionally, the sick were treated and cared for by the VOC in their hospital.

On “Susanna” and “Gatemisse”, those who had descended from France or who had previously remained ill in Vlissingen also traveled with them. A total of 18 women and 11 children, for whom extra payments had to be made, also made the trip, including the family of Colonel von Hügel, who was not yet married (whose eight-year-old son Theobald (see section Individual fates below ) was hired as a flag junior to cover the private costs to save the crossing).

Cape of Good Hope

The 1st Battalion arrived in Cape Town from October 25, 1787 to January 20, 1788, the 2nd Battalion from March 29 to July 4, 1788 .

After its arrival in Cape Town, the regiment remained stationed there as a protection force until 1791 and was housed in its own barracks. It was subordinate to the local governor (from 1785 Cornelis Jacob van de Graaff, from July 1791 Johann Isaac Rhenius, from 1793 Abraham Josias Sluysken) and the garrison commander (Colonel Gordon, commander of the Dutch battalion stationed there).

In 1795 Abraham Josias Sluysken formed the first military unit with Coloreds , which were used against British forces and against indigenous groups. These military personnel fought as riflemen in the infantry and cavalry of the Cape Corps .

In addition to the normal garrison service (daily drill), parts of the regiment were assigned several times to Muizenberg on False Bay to guard the coast. So also in October 1788 a major, two captains, four lieutenants and 300 men, also from the artillery a captain lieutenant and 8 cannons, also an escadron from the local cavalry , when five French ships entered False Bay. In the summer of 1789, a command of 50 men under one officer and six NCOs guarded a stranded VOC ship for three months until the cargo was salvaged.

For misconduct in and out of service, there were the usual punishments for soldiers in Europe as well as forced labor in the quarries on Robben Island with loss of wages. In the case of recurrence, this lasted until the end of the service period, after which the punished person was transported back to Europe by the next ship - with the loss of his gratification . On 2/3 In July 1789, some soldiers rebelled because of poor food. Two ringleaders were sentenced by the military court of the regiment to death, but Colonel von Hill decided that the beede delinquent Weis Hard and Martin not streamlined alive but for the first Hung of death anxiety, and the delinquent Müller to six times alleys run (running the gauntlet) Being condemniert should .

Otherwise life in Africa was like living in a garrison in Württemberg. Treffz (see individual fates below ) wrote home in a letter dated January 22nd, 1789: “Our barracks are very beautiful and undoubtedly a barracks where you may seldom find it only in Germany. But for a soldier Cap is not long the earthly paradise, as it is described in Germany, but you have enough when you are healthy, and you have enough to do if you want to get by with honor. " The soldiers could do business outside of the service float. Several officers and NCOs married the wives they had brought with them (Colonel von Hügel on February 15, 1788, his partner Anna Maria Kayserin) or local residents.

The regiment's losses - mainly due to illness - totaled 532 men by May 21, 1791. On December 13, 1790, Lieutenant Colonel Wilhelm von Franquemont died, his successor as commander of the 2nd Battalion was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel Maximilian von Jett.

Celebes Island (today's Indonesian island of Sulawesi)

Because of a disturbance that broke out on the island of Celebes (island between Borneo and New Guinea ) at the beginning of 1789 , the governor-general of Batavia requested a corps of 300 men from the Cape for an expedition. The governor on the Cape then set up the Orange Battalion with 200 men from Dutch national troops and 100 men from the regiment under officers from Württemberg exclusively. The Württemberg people were all volunteers.

The battalion, under the command of Hauptmann von Boehnen, was divided into three divisions under first lieutenant Karl Joseph Gaupp, Philipp Jacob Gaupp and Carl von Wollzüge, who were also promoted to captainleutnants. There were also six other officers, two field clerks, a Fourier, two sergeants, four non-commissioned officers, two private and five minstrels.

The battalion sailed on August 14 with the ship Eensgezindheid from False Bay and reached Batavia on October 31, where it was initially stationed at Fort Meester Cornelis. On December 8th the journey with "Horn" took place, but instead of at Makassar it landed on December 27th in the bay of Bontheim in the south of the island. The battalion moved to Bulekomba, five miles away, drove out the local population and stayed there for several weeks without any further action. In June 1790 the battalion was split up. The Württemberger came to the island of Solor under Lieutenant Karl Joseph Gaupp , 100 Dutchmen came to Makkasar under Lieutenant von Wollhaben. From June 18, this department moved on to Surabaya Bay (arrival July 1), from there three weeks later to Samarang (arrival July 24). In November 1790, the governor general ordered the Württemberg division with the oldest captain and two lieutenants to remain in India, and the remaining officers to return to the Cape. These sailed from November 2nd with Schonerloo to Batavia , from there on November 23rd with St. Laurenz and arrived again on the Cape on April 2nd, 1791, where parts of the regiment had already sailed to Java (see next section).

The detachment "Kapitänleutnant Gaupp" remained on the island of Solor and joined the regiment in Batavia on April 28, 1792 with a strength of 1 captainleutnant, 2 lieutenants and 69 men.

depot

After the regiment had been relocated as described below, a depot (replacement troop unit) and the hospital remained on the Cape . Here the sick were to recover and the replacement sent on from Europe was supposed to recover from the previous trip before it was sent on to the regiment. The guide was initially the sick Major von Dhen, after his recovery and onward journey to Ceylon, Captain Johann Christian Friedrich von Hügel, as a medical officer, Surgical Major Dr. Friedrich Ludwig Liesching in Cape Town. The governor did not approve of Hügels' intention to wait until the next transport from Europe arrived before further transport. He described the situation in a report to the Duke: “So far, they have mostly arrived here after a long, often six-month journey and, if they were not bedridden, had to continue their journey to Batavia with the same ship after 8 or 10 days, Which means that if 5 men are to come to Batavia in good health, 25 recruits have to be sent. ”In 1792 100 recruits arrived in four transports, in 1793 282 recruits in six transports from Europe , and around 460 men were sent to India in at least 16 "Transport" forwarded. The last "transport", 1 captain, 1 cadet sergeant, 1 private and 19 commons, reached Batavia on February 5, 1795.

When the colony was occupied by the British in 1795, the strength of the depot was 2 officers, 2 medical officers, 8 non-commissioned officers and 16 soldiers. During the defense, Hauptmann von Hügel received command of 80 infantrymen, 2 companies of cavalry, 200 " Hottentots " and 50 artillerymen with 3 cannons. The soldiers of the depot were declared prisoners of war after the occupation. They were given six days to retire from service and remain in Cape Town as private individuals or be transported back to Europe as prisoners of war on the first ship. The two officers, Captain von Hügel (married, with four children) and Lieutenant Martin, opted for captivity, the two medical officers, Surgery Major Dr. Liesching ("because he earns more there than in poor Württemberg") and surgery major JG Pösselt resigned. Of the soldiers, 1 sergeant switched to British service, 8 returned to Europe, 2 remained sick in the hospital, 13 dropped out and remained at the Cape as a craftsman or farmer. When the British returned the colony to the Dutch in 1803, the depot was no longer established.

India

In the regiment's files, the entire Southeast Asian region - in contrast to today - is referred to as India. In addition to large parts of the East Indian Islands, the Dutch East India Company had owned Ceylon since 1658 and also had bases in the east of what is now India .

The VOC decided on October 1, 1790 to move the regiment to East India. The Württemberg representative in Holland, Major von Penasse, did not find out about it until a month later. Duke Carl Eugen couldn't do anything about it because of Article 23 of the Subsidy Treaty. His attempt to increase the annual payment by 10,000 florins as compensation also failed.

The order of the VOC to “send the Würtemberg regiment to Batavia in order to be sent on from there to Java's north-east coast, in order to be employed there as we will determine in the letters to be sent to the High Government of India " And to ship " a whole or half a company with accessories " to Batavia with any suitable ship as quickly as possible , arrived at the Cape on January 17, 1791.

The transfer of the regiment began at the beginning of March (see adjacent table). Sick people who could not be transported were sent to Java in December on the ship “Sybilla Anthonetta”.

While the regimental staff, the Colonel Company, the Jäger Company (von Wolzüge) and the Fusilier Company v. Nezzen were still waiting for their departure, a ship from Ceylon arrived on September 14, 1791 with a request from the Dutch governor there to quickly send some companies to protect against the local population. For this purpose, the remainder of the regiment was determined, which left after a short time (see adjacent table).

Ceylon

Ceylon is an earlier name for today's Sri Lanka , which dominated the VOC in large parts since 1658.

On December 28, 1791, "Zeyland" arrived in Colombo . The fusilier companies von Winkelmann and von Vellnagel were already there (under Premier-Leutnant Koch, Hauptmann von Vellnagel was on vacation, the company commander Captain Hellwag had died during the crossing), which had been assigned here from Batavia. The Jäger-Company (under Lieutenant Captain von Woliehen) was sent on to Batavia, since there were now enough troops on Ceylon. Thus were in Ceylon

- the regimental staff

- the Colonel Company under Lieutenant Hoffmann

- the Lieutenant Colonel Company under Lieutenant Friedrich von Franquemont

- the major company

- the Grenadier Company under Captain Beurlin

- the Winkelmann fusilier company

- the Fusilier Company von Vellnagel under Premier-Lieutenant Koch, later the Fusilier Company Koch

- half the artillery company

The companies of the regiment were distributed on the orders of Governor Willem Jacob van de Graaff: The regimental staff with the Colonel Company (under Captain Hellwag) was transferred by ship to Ponto Gale on December 30th , the staff remained there, the Colonel Company ( now under Captain Hoffmann) but was transferred to Matara on January 24, 1792 (there were already 2 companies of the "Regiment Meuron"), where Hoffmann was in command of "the garrison and the troops detached in the ensuing dissavony in Sengalen and in the Magampotte ” received. The Fusilier Company von Vellnagel first came to Fort Negombo (7 hours from Colombo) and marched from December 26, 1791 to Fort Oostenberg on the east coast, the Lieutenant Colonel Company (under Lieutenant Captain F. von Franquemont) to Triconomale , also on the East coast, the fusilier company von Netzen on March 14, 1792 to Batticaloa, also on the east coast, only the fusilier company von Winkelmann remained in Colombo. The staff returned there on 1792.

Other changes followed. At the end of March, Captain Hoffmann gave command in Matara and the Colonel Company to Oberleutnant von Reitzenstein, took over the previous company from Vellnagel as well as command of the companies in the northeast of the island and exchanged them: his fusilier company Hoffman after Triconomale, the Lieutenant Colonel Company to Oostenberg. The Fusilier company of Winkelmann was from December 1792 to May 1793 in Jaffnapatnam stationed, then again in Colombo.

The living conditions on Ceylon were not as bad as in Batavia, nevertheless many members of the regiment died here too, so that the strengths of the companies steadily declined.

In 1794, at the request of the British Governor of Madras, the VOC government in Batavia sent a corps of eight companies under Colonel Pierre Fréderic de Meuron to India. The corps also included two companies from the Cape Regiment, the Lieutenant Colonel Company (under Lieutenant F. von Franquemont) and the Vellnagel Fusilier Company (under Lieutenant Captain Koch). They were embarked for Negapatnam (Nagapatam), a VOC base on the Indian mainland. It is not known whether the troops actually made it to Madras. In any case, the two Württemberg companies soon returned to Ceylon.

In March 1795 the Colonel Company and the Fusilier Company Winkelmann with a total strength of 223 men were relocated from Ponto Gale to Colombo and in December 1795 were divided into three companies, the new of which was that of Christoph Friedrich von Vellnagel, who was promoted to major at the same time became: Major Company von Vellnagel (under Lieutenant Captain Friedrich Karl Hallwachs).

On August 3, 1795, British warships appeared off Triconomale. After a short siege, the crew surrendered to the Dutch commandant, Major Fornbauer, and were taken prisoner, including the Württemberg fusilier company Koch , who was last stationed there .

On August 26th the British ships appeared in front of Fort Oostenburg, commanded by Captain Hoffmann. At first he refused to hand it over, but soon also had to surrender due to a lack of food and water. As a result, the two companies of the regiment stationed there were also taken prisoner. On February 16, 1796, Governor van Angelbeck surrendered Colombo to the British, the rest of the regiment including the staff were taken prisoner, most of the officers and 27 men to Madras. The four flags that were taken from Ludwigsburg also fell into the hands of the British.

Two officers died in Madras, including Major von Vellnagel on July 21, 1796. Since the officers were not released by the VOC, they were transferred to Europe as prisoners. They sailed from Madras on October 17, 1798, reached the Cape on January 3, 1799, sailed from there on January 16 and reached Dover via St. Helena (stay February 8 to May 8) on July 11 and were allowed ashore on July 20th. From August 9th to November 9th they had to stay in Lichfield (at their own expense with 1 1 ⁄ 2 shillings daily from the British government and 1 shilling from the Dutch government.) With 10 pounds travel money they traveled via London , Yarmouth (departure 24 November) and Cuxhaven (November 27) to Amsterdam , where they received their arrears pay and six months vacation to Germany. They traveled home from there at the end of January 1800 and arrived in Stuttgart on February 5th . Except for First Lieutenant von Plomann and Fahnenjunker Bloesch, who later returned to India, they retired from the service of the VOC. Most of them were accepted into the Württemberg troops just a month later.

Under pressure from the British, 230 of the captured NCOs and men entered their service. The rest remained in captivity on Ceylon. After the Peace of Amiens in 1802, Ceylon remained British property and the prisoners were released. Since the British did not immediately transport them to the regiment in Java, they were taken prisoner again in November 1803 (after the fighting started again) and were only shipped to Java in 1806 without a formal release.

Colonel von Hügel was able to stay on Ceylon and tried to continue to lead the parts of the regiment stationed on Java from Ponto Gale and continued to send reports to Württemberg. He died on June 30, 1800. After his death, Captain Karl Philipp von Winkelmann - although he was also in captivity on Madras - took over responsibility for the Württemberg soldiers on Ceylon and was promoted "provisionally" to major. The British governor of Ceylon, Sir Thomas Maitland, sent him to Batavia in 1805 to arrange the transfer of the regiment's prisoners of war on Ceylon.

According to a report from Hügels, 779 men had arrived on Ceylon, 31 residents were hired, 3 new arrivals from the Cape, 5 from other companies and 3 from Batavia. Of these, 216 died, 12 deserted, 55 were transferred to the regiment in Batavia, 7 to the noble company (VOC) and 3 were exchanged for the National Troupes . Also went from 3 dimittierte Officiers , 17 in Ceylon Beabschiedete and 3 as unfit convicts. 476 were taken prisoner.

East Indies

Arrived in Batavia in 1791

- the lieutenant colonel company

- the fusilier company of Winkelmann

- the Vellnagel fusilier company

- These 3 companies were sent on to Ceylon in autumn 1791.

- the major company of Stakmann

- the Major Company from Ostheim

- the Donop Fusilier Company

In 1792 the Jäger-Company was added from Ceylon .

The governor general of Batavia was not prepared for the arrival of the troops. There were no accommodations available, so bamboo barracks were built on the ramparts.

At the end of 1792, the Donop Fusilier Company was separated from the regiment by the Batavian government and relocated to the Moluccan island of Amboina . She remained there without any connection to the regiment. After Hauptmann von Donop's death, Captain Philipp Jacob Gaupp took over the company. After the surrender of the governor of Amboina in 1796, Captain Gaupp and the whole company with a strength of only 79 men entered British service, but with the proviso that the company should continue to be considered a Württemberg troop and may return to the regiment if the opportunity arises add to this. The company was used by Great Britain in the capture of the islands of Banda and Ternate . Nothing is known about the whereabouts of the company after Gaupp's retirement from British service in 1804.

The rest of the battalion was also relocated: the battalion staff and 3 companies were stationed in Semarang, 1 company in Surabaya , 1 company in Fort Meester Cornelis. The Jäger company , which arrived from Ceylon in January 1792 , also came to Java and was stationed in Semarang . In the following years, parts of the companies were repeatedly commanded to Batavia for a time, and they were also used against French ships on ships of the VOC and the British, who were initially allied with Holland.

A small detachment of the regiment even reached Beijing . In 1794, the government of the VOC in Batavia demanded that Major Schmidgall provide a bodyguard for an embassy to the court of the Emperor of China . A sergeant, a drum, a piper and nine soldiers were assigned to do this. One of the soldiers died in Beijing, nine deserted on the return journey.

After the death of Lieutenant Colonel von Jett on October 19, 1791, Major Karl von Ostheim became commander and soon afterwards was promoted to lieutenant colonel. At the offer of the VOC to become commander of Batavia and commander of all troops in India, he resigned from the regiment in late 1792 (he died shortly afterwards on February 20 of the following year). After him, Captain Johann David Gottlieb von Schmidgall took over the leadership and was promoted to major, in April 1798 to lieutenant colonel.

Due to the climatic conditions, the mortality was very high.

“Because of the swamps, the air is pestilent. ... European newcomers in particular are at risk. Almost everyone gets the fever. ... Half of the resident Europeans die every year. ... The garrison recruits rarely come from Holland; they are mostly Germans, advertised with violence or ruse. Despite the right to return home, they almost always have to be recruited: their wages are too low to pay for the trip to Europe. The government should pursue the barbaric policy of intercepting all correspondence between these unfortunate soldiers and their homeland; so they are cut off from their homeland and its help. ... Shortly before our visit, the Duke of Württemberg had sent one of his regiments to Batavia on the basis of a trade deal with the Dutch company; but a large part of his soldiers and officers had died within a year. ... Sometimes there are as many soldiers in the hospital as would be necessary for duty. "

Since there were no more personnel replacements from Europe from 1794, the strength of the troops steadily decreased, so that locals were also hired. Other officers and non-commissioned officers, like von Ostheim, entered the service of the VOC. Non-commissioned officers were promoted to replace the deceased and resigned officers, as were (often unsuitable) crews to non-commissioned officers. The condition of the armament and equipment also deteriorated constantly, so that the fighting strength of the battalion steadily decreased and normal service was no longer carried out. In the autumn of 1805 a detachment of one and a half companies was moved to the Cheribon province in western Java to put down an uprising by the local population. The condition of the battalion clearly shows the composition of the detachment with a total strength of 85 men: It consisted of 20 Europeans (4 officers, 2 sergeants, 1 non-commissioned officer, 13 commons) of 65 local non-commissioned officers and men. Of these, only half returned.

“Already in Batavia the ugliest picture was drawn up of the broken morality of most of the NCOs and people. ... I therefore found most of the NCOs and commoners extremely devoted to drunkenness, highly malporpre in their daily suit, besides the duty many wandering around the streets without shirts, shoes and stockings, often very drunk. ... I found the health of the people largely in shambles; many obsolete over their years; several profound, confused. ... The daily decrease in the number of our people, ... the lack of capable subjects to be non-commissioned officers, the worn-out faculties of the mind and body of the greater part of the people, the number of the unusable, this had many offenses here and the repeated threats of abdication, incorporation, with the complete dissolution. "

When the members of the regiment released from British captivity in 1806 came to Semarang, the sick Lieutenant Colonel von Schmidgall (the First Major von Nezzen had also been ill for years and had applied for his release) in the autumn of 1806 transferred command of the Württemberg troops to the first in This year in Semarang really promoted Karl Philipp von Winkelmann to major. By taking decisive action to restore discipline on the one hand and improving equipment - as far as the limited resources allowed - on the other hand, he succeeded in making the battalion operational again.

After Louis Bonaparte's accession to the throne in the Kingdom of Holland in 1806, all officials and officers of the VOC were released from their previous oath of loyalty and committed to the new king.

At the end of 1807 the battalion had a total strength of 229 men. On March 1, 1808, Lieutenant Colonel von Winkelmann received an order from the Marshal of Holland and Governor General of the Dutch East Indies, Herman Willem Daendels , that the regiment had been disbanded and taken over into Dutch service. Several of Winkelmann's protests were unsuccessful. On April 5, he was ordered that “at the next report, the regiment's name, uniform and flags must disappear” . With that the regiment ceased to exist. The reports from the Winkelmanns to King Friedrich did not reach Stuttgart until 1809, but did not result in any reaction.

Losses of the regiment

The regiment was hardly involved in any action. Most of the losses were due to illness. In contrast to the troops in Europe, the desertions did not play a major role, since one could not disappear to other countries in the colonies.

A few figures should make this clear. 137 died during the voyage, and 532 (30% of those marched off) in the five years on the Cape up to May 21, 1791. 216 men died on Ceylon in four years, only 12 deserted. According to a report from Lieutenant Colonel von Ostheim received from Samarang on January 30, 1792, Colonel von Hügel reported that 516 men of that part of the regiment had died since leaving the Cape in May 1791.

Exact numbers of the total losses can no longer be determined. Around 2,300 of the displaced died in the regiment. Only approx. 450 were taken into British captivity and partially entered service there, 229 were accepted into Dutch service, approx. 50 were dismissed; Almost nothing is known about their further fate. Only about 100 are likely to have returned.

Win of the duke

While the regiment ruled in Württemberg

- until October 24, 1793 Duke Carl Eugen

- until May 20, 1795 Duke Ludwig Eugen

- until December 23, 1797 Duke Friedrich Eugen

- from December 23, 1797 duke, from May 1803 elector, from January 1, 1806 King Friedrich I.

who each received the income from the rental of the regiment. Carl Eugen regarded this as his private income, at the latest from Friedrich I the income was added to the war chest.

The total actual profit can only be determined approximately today. After a created by the Württemberg President of the Military Council of the accounting profit to April 1793 448.390 was fl. The total profit can be roughly at least 780,000 fl. Empire Gulden estimate.

- From that

- "Office costs" 8 fl. 10 items per man = 18,513 fl. 30 items

- 36 florins advertising money for 1,821 NCOs and crews = 65,556 florins

- Armament and equipment (firearms, sabers, cartridges, leatherwork) estimated at 25,000 fl.

- remain at least 180,000 fl.

- 72,000 florins for the march to Holland

- From that

- for marching through France 5,000 fl.

- Cost of the transport (see above paragraph march to Holland ) estimated 3,000 fl.

- Costs for French hospitals 5,688 livres 7 sols 3 deniers, equivalent to around 2,844 fl.

- remain at least 60,000 fl.

- for personnel replacement

- From 1788 to 1796 65,000 florins annually, from 1797 to 1808 36,000 florins.

- From that

- for advertising to Major von Penasse in Middelburg annually until at least 1794 20,000 florins, a total of 120,000 florins

- for " table money " to Colonel von Hügel 3,000 florins, a total of 36,000 florins.

- for "pensions" to the agents of the VOC (Lieutenant Colonel von Knecht up to 1798 1,000 fl., Lieutenant Colonel Gradmann 1,000 fl.) a total of 23,000 fl.

- The cost of the merits of the Duke's representatives in Holland, bankers' expenses and commissions, or exchange rate losses can no longer be determined.

- remain at least 700,000 fl.

These 940,000 florins argent d'Hollandaise amount to around 780,000 florins imperial gulden .

In addition, there were transfers from the regiment (withheld fees from officers on leave, retained wages from punished or sick soldiers, wages paid by the VOC for three months to the deceased, etc.). A settlement of the regiment from 1786 to 1792 shows 57,650 florins alone.

Others

Individual fates

The data of many people in the regiment are supported by various sources. The regimental priest Magister Johann Friedrich Spoenlin and his successor Haas z. For example, like the pastors in the duchy, they kept a parish register in which 1,521 dead, 15 weddings (the last on March 1, 1795) and 31 baptisms (the last on June 27, 1796) are recorded.

Some of its specially mentioned here.

- Colonel Theobald von Hügel (born April 20, 1739 in Strasbourg , † July 16, 1800 in Porto Gale on Ceylon), in the Württemberg military service since 1760 , was the first commander of the regiment. It was not until February 15, 1788 that he married Anna Maria Kayserin († August 21, 1822 in Samarang) on the Cape.

- Theobald von Hügel, son of Colonel Theobald von Hügel (* 1779, †?)

- At the age of eight, before leaving Vlissingen, he joined the regiment as a squire, 11 March 1790 second lieutenant, 1796 premier lieutenant, 1805 as premier lieutenant from captivity from Madras to Samarang.

- Johann Christian Friedrich von Hügel (*?, † January 1805 by suicide in Middelburg; son of the Württemberg general field witness Johann Andreas von Hügel, nephew of Colonel Theobald von Hügel)

- He joined the regiment in 1787 as the premier lieutenant and adjutant to his uncle. March 4, 1788 Hauptmann, from 1791 to 1795 he was in command of the depot on the Cape and came to Great Britain as a prisoner.

- After his return to Württemberg in 1799, he became the Duke's extraordinary envoy in The Hague as major .

- Lieutenant Colonel Franz Karl Philipp von Winkelmann

- He joined the regiment in 1787 as a premier lieutenant. First shipped to Batavia with the 2nd Battalion in 1791 as a captain lieutenant of a fusilier company, he was transferred as a captain with his company to Ceylon in the same year. There he was captured by the British in 1796. After the death of Major Vellnagels on April 21, 1796, he took over responsibility for the parts of the regiment on Ceylon and in Madras and was temporarily appointed major. At the end of 1805, the British Governor Sir Thomas Maitland sent him to Batavia on a parliamentary ship to organize the collection of the prisoners of war (he was officially released from captivity with permission to fight against Holland's enemies again, and took his Family with). After completing this job, he was able to obtain confirmation of his promotion to major in 1806 and joined the 2nd Battalion in Samarang. In the autumn of 1806 the sick major von Schmidgall gave him command of the Württemberg troops in rear India. After his death on January 5, 1807 and the resignation of Major von Nezzens, he was the longest serving officer in the regiment and was promoted to lieutenant colonel by the Dutch governor in September 1807 at the suggestion of the officer corps. With the dissolution of the regiment, which he could not prevent, he entered Dutch service in 1808.

- Philipp Jakob Gaupp (born April 30, 1764 in " Lerach in Switzerland", † August 16, 1852 in Baden-Baden ) as the last surviving officer of the regiment and the last student of the High Charles School. His father Georg Friedrich had been an officer in British service in India. From 1778 to 1783 he was a student at the Hohen Karlsschule in Stuttgart (like seven of his brothers, incidentally, including Karl Joseph, who was also an officer in the Cape Regiment) and in 1783 he joined the “Schéler Regiment” on Hohenasperg. He enlisted in the Cape Regiment and was Premier Lieutenant in the 2nd Battalion. In 1789 he was a volunteer while being promoted to lieutenant captain with the Orange Battalion on Celebes and returned to the Cape in April 1791. He sailed with the battalion to Java, was stationed in Samarang and after the death of Captain von Donops in 1793 took over his company on Amboia. In 1794 he married Jesuina Treno, the daughter of a Dutch resident, with whom he had a son and two daughters. After the colony was taken over by Great Britain, he joined British services on February 16, 1796 and was there during the conquest of the islands of Banda and Ternate . After the Peace of Amiens in 1802 he stayed in Madras until 1804 , " took his leave, subject to a lifelong full salary as captain " and traveled 1804/1805 via Great Britain, Hamburg and Frankfurt to Durlach. To his letter of June 14, 1805 to Elector Friedrich, the latter had an answer on June 18, 1805, “if he is within the Elector. States that he will be arrested and, in accordance with military law, will be interrogated and treated according to the allegations made against him ” .

- Franz Joseph Kapf (born January 15, 1759 in Mindelheim , † August 9, 1791 in Batavia on Java); According to family tradition, he is said to have drowned while disembarking with his slave girl Abigail, who was bought in Cape Town.

- From 1774 to 1780 he was a student at the High Charles School (he received a total of eight prizes), and then a supervisory officer and teacher of mathematical geography and algebra there. He was friends with Friedrich Schiller and lived with him in a room after his studies. In a drawing by the painter Viktor Wilhelm Peter Heideloff , on which Friedrich Schiller reads “ The Robbers ” to his comrade , he is sitting in the front right. Kapf marched out of Ludwigsburg on September 2 as staff captain in the 2nd Battalion.

- August Franz Treffz (born June 7, 1770 in Habitzheim , † 1819 lost during an expedition to the Moluccas)

- He joined the regiment in 1786 as a sub-gunner and signed the surrender of the VOC in Vlissingen as a corporal. As a sergeant he arrived in Batavia with the Vellnagel company in 1791 and was transferred to Ceylon with them at the end of the year. From January 1792 he was with the detachment in Triconomale, where he continued to sign up as premier sergeant on April 1 with 20 florins pay. On June 21, 1794 he became a second lieutenant ("200 pounds added to the equipage as a change from Hügel") and wrote home: "Now I've finally made my fortune in the military class." In 1795 he was taken prisoner by the British and with the others Officers to Madras. There he married the daughter of the former Dutch commandant of Palikat . Through these connections he managed to escape to Samarang, where, according to a list dated April 8, 1800, he was Premier Lieutenant in the Artillery Company. Lieutenant Colonel Schmidgall sent him as a courier to Württemberg at the end of 1803. After an adventurous journey (initially at his own expense, the money was only reimbursed after repeated insistence by the Duke) he arrived there at the end of March 1804. Before his departure, he received his patent as captain-lieutenant dated January 23, 1804. He returned to Samarang and entered the Dutch service when the regiment was dissolved. In 1811 Java was occupied by the United Kingdom and Treffz became the second pack house manager in Batavia with a monthly salary of 500 florins. When Java became Dutch again in 1811, he founded his own trading company, but returned to the Dutch service a short time later as commander of a sniper corps. Promoted to lieutenant colonel, he became commandant of Batavia. His planned appointment as a resident of Borneo failed because not enough troops were available to occupy them. After the death of his wife in 1818, he wanted to return to Württemberg. In 1819, however, he led a military expedition to one of the Moluccas Islands on behalf of the Dutch government, where he remained missing.

- Johann Martin Canzleiter (born December 11, 1762 Stuttgart, † June 8, 1825 in custody in Stuttgart).

- Parents: Johann Martin Canzleiter, Princely Vorreiter, and Anna Maria geb. Pfäffle. Canzleiter joined the regiment in 1786 as a sergeant, became premier sergeant in 1787, moved with the regiment to Ceylon in 1791, became 2nd regimental quartermaster in Ponto Gale in 1792 (purchase and settlement of large and small outfits). In 1795 Colonel von Hügel assigned him to Java, where he also handled his private business, in 1796 he became 1st regimental quartermaster and in 1799 captain. In 1801 he entered the Dutch service, returned to Europe in 1803 via the Cape of Good Hope (also here private business for the late Colonel von Hügel and his heirs), where he arrived in 1804. He was married.

- 1805 Castle steward and clergyman in Winnental, councilor

- In 1805 he was commissioned by Elector Friedrich to collect the unpaid wages in Middelburg.

- 1807 court camera administrator in Winnenden

- In 1822 he was arrested during the trial (see below) and died in prison.

- 1823 suspension from the office of court camera administrator

- Kaspar Bohn (* 1768 in Lauffen am Neckar ), in

1789 he moved to the "Regiment Meuron" and with this in 1795 in British service, where he resigned in 1806 and returned to Europe.

We George the Third, by the grace of God King of Great Britain, & c. & c. After Gaspard Bohn, born by Laufenkocher in Württemberg, 38 years old, without profession, religion, served faithfully and honestly in our Meuron regiment for 18 years as a sergeant and behaved well and bravely at every opportunity we gave. So we have said goodbye with nine and twenty pounds, ten shillings and 32/4 pence sterling as a reward for his loyal service rendered to us so that he is now free to return to his home.

So we order all and every military and civil authorities in our states, and request all and every foreign authorities not only to allow said Gaspard Bohn to pass freely and unhindered, but also to give the same help and assistance.

As a document and confirmation, the present farewell in the Canzley of the General Inspection of the foreign troops in our service has been made out and given the customary seal.

Given Lymington, April 5, 1806

By Order of Lieut. Gen Whitelodge

W. Stewart, Colonel

(Seal)

The back of the note says:

I hereby confess that I have correctly received my wages or wages, along with all arrears of wages and military clothing of all kinds, as well as all other just claims from the time of my engagement in the regiment mentioned here up to the day of my departure; Which I hereby confirm by my signature.

Husum on April 26th 1806

Bean

Paid off by me Cha. Kentzinger, captain & commissary

Husum 26 th April 1806

- Gottfried Adam Kohler (* 1768?, †?)

- Gunsmith in the Cape Regiment. From 1809 geometer at the Royal Bavarian Tax Register Commission in Munich. Kohler, who was probably the last living member of the Cape Regiment, reported in 1847 after learning about the process of the withheld pay from the Augsburger Allgemeine Zeitung.

They also made a career in the Dutch service

- Wilhelm Beurlin, 1787 State Captain of the Colonel Company, 1832 Colonel and Commander of Madura.

- Karl Joseph Gaupp, first lieutenant in 1787, lieutenant colonel in Java in 1805.

- Karl Friedrich Hallwachs, second lieutenant in 1787, retired lieutenant colonel in 1832.

- Karl Eugen von Jett, 1787 Second Lieutenant, 1832 Colonel and Commander of the 2nd Military Division in Java.

- Carl von Ostheim (born April 3, 1761 in Stuttgart, † 1783 in Batavia): 1783 captain of the bodyguard, 1790 major, 1792 colonel, 1792 colonel in the service of the VOC and commander of Batavia.

- Carl Alexander von Ostheim (born December 13, 1765 in Ludwigsburg, † 1785): lieutenant in the guard on foot, 1787 first lieutenant in the Cape Regiment, 1803 captain, 1807 major in Dutch service, retired around 1820.

- Johann Friedrich Roessler, promoted from Seconde Sergeant to Seconde Lieutenant according to the report of April 2, 1791, retired Lieutenant Colonel in 1832.

- Carl von Wolzog, 1787 Premier-Lieutenant, 1796 as captain-lieutenant, farewell to the regiment and as captain in the Dutch service, 1798 major and chief of the artillery in Samarang, 1807 colonel, 1808 farewell to the military, † July 8, 1808 as inspector general of the forests on Java.

Of the returned officers, in addition to those already mentioned, later served in the Württemberg Army

- Friedrich von Franquemont (March 5, 1770, † January 2, 1842): He joined the regiment as a lieutenant and was captured by British troops in Trikonomale on Ceylon in 1795 and transported to Great Britain. From there he returned to Württemberg in 1800 and became a captain in the Seeger battalion, major in 1805, lieutenant colonel and commander of the Kronprinz battalion in 1805, colonel and commander of the Kronprinz infantry regiment in 1806, in 1809 commander of the 1st infantry brigade, in 1813 general and commander of the Württ. Army Corps, general of the infantry in 1814 and 1815 and commander of the Württemberg expeditionary corps in France, 1816 to 1829 Württemberg Minister of War .

- Karl von Franquemont: 1814 Colonel and Commander of the Guards Regiment on Foot, 1817 Commander of the 6th Infantry Regiment, 1823 Farewell, † July 20, 1830.

- Christian Johann Gottgetreu Koch (* July 14, 1769, † March 29, 1826): 1800 captain in the Beulwitz battalion, 1805 major, 1806 battalion commander, 1809 colonel and commander of the Kronprinz infantry regiment, 1812 major general and commander of the 2nd Infantry Brigade , 1813 Lieutenant General, 1815 Commander of the 1st Infantry Division, 1820 Farewell.

- Carl August von Neuffer (* March 6, 1770, † January 6, 1822): 1800 Premier Lieutenant in the Seeger battalion, 1801 captain, 1805 company commander in the Seckendorf battalion, 1809 colonel and commander of the 2nd foothunter battalion, 1813 colonel and commander of the 1st infantry -Brigade, 1815 envoy in Berlin, 1816 envoy in London.

- Mrs. A. von Reitzenstein: 1800 captain in the Beulwitz battalion and company commander in the Obernitz battalion, farewell in 1805, reactivated in 1815 and as major commander of the Altensteig Landwehr regiment, farewell in 1816, † December 2, 1823 in Ludwigsburg.

11 officers of the regiment were students of the High Charles School :

- Friedrich von Franquemont (born March 5, 1770 in Ludwigsburg , † January 2, 1842 in Stuttgart ): July 1775 to August 1787

- Carl Joseph Gaupp (born March 21, 1763 in Lörrach , † January 9, 1828 in Batavia ): July 1773 to April 1783

- Philipp Jakob Gaupp (born April 30, 1764 in Lörrach, † August 16, 1852 in Baden-Baden ) December 1778 to April 1783

- Johann Christian Friedrich von Hügel (born September 14, 1764 in Strasbourg , † January 12, 1805 in The Hague ): February 1772 to April 1784

- Christian Johann Gottgetreu Koch (born July 14, 1769 in Stuttgart, † March 29, 1826 in Ludwigsburg): August 1786 to 1787

- Carl von Ostheim (born April 3, 1761 in Stuttgart, † 1783 in Batavia): April 1773 to March 1783

- Carl Alexander von Ostheim (born December 13, 1765 in Ludwigsburg, †?): April 1773 to October 1785

- Johann Daniel Gottfried Schmidgall (* July 18, 1756 in Oßweil, † 1807 in Java): July 1771 to March 1779

- Franz Karl Philipp von Winkelmann (born June 17, 1757 in Meiningen , † 1820 in Samarang, Batavia): February 1773 to March 1780

- Carl August von Wolhaben (born October 26, 1764 in Meiningen, † July 8, 1808 in Samarang, Batavia on Java): July 1774 to May 1775

The regiment in literature

- The poet Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart , captured on the Hohenasperg near Ludwigsburg, wrote on February 22nd, 1787: “Next Monday the Württemberg regiment destined for the foothills of good hope will leave. The deduction will be like a corpse conduction, because parents, husbands, lovers, siblings, brothers, friends lose their sons, wives, sweethearts, brothers, friends - probably forever. I made a few lamentations on this occasion to pour comfort and courage into many a hesitant heart. The purpose of poetry is not to brag about genius, but to use its heavenly power for the good of mankind. ” The Cape Song and the poem For the Troop were printed in a brochure and were extremely popular. Schubart also set these verses to music.

The cape song

|

Up! you brothers and be strong |

At Germany's border we fill |

For the squad

Come on, comrades! The warlike tone of

the drums and pipes already encourages us.

Fresh, buckle

your knapsack around your back and send yourselves off to the march, just don't look around.

For it is difficult to say goodbye to friends and girls,

And good soldiers do not cry very much;

They obediently obey the guide's commandment

and joyfully prepare for parting and death.

Doesn't the sun and moon also

shine on the Cape And don't the stars shine down there?

And don't the winds blow in the blooming grove?

Is there no game there, no fish, no wine?

It is also said that there is a rosy mood

there, girls pretty blackish, pretty whitish and brown:

And if soldiers have gold, girls and wine,

the princes cannot be happier

- Johannes Scherr describes in his novella Schiller - Dem Freunde Dr. Lorenz Brentano, Consul of the United States in Dresden, appropriated. Zurich, May 1873 in Section IV the march of the 1st Battalion from Ludwigsburg.

- Friedrich Schiller also takes up the issue of sold subsidy regiments in his drama " Cabal and Love ".

The lawsuits for withheld pay