Zinc wall

| Zinc wall | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Zinc wall from the west ( Lungau side) |

||

| height | 2442 m above sea level A. | |

| location | Styria and Salzburg , Austria | |

| Mountains | Schladminger Tauern , Lower Tauern | |

| Dominance | 0.63 km → cousin peaks | |

| Notch height | 82 m ↓ Holzscharte | |

| Coordinates | 47 ° 16 '8 " N , 13 ° 40' 58" E | |

|

|

||

| rock | Migmatic paragneiss | |

| particularities | Ore deposits (mining), "first Tauern tunnel" (since 1984 tunnel educational trail) | |

The zinc wall is a 2442 m above sea level. A. high mountain in the Schladminger Tauern on the border between the Austrian federal states of Styria and Salzburg . The mountain has previously rich ore deposits and has been shaped by more or less intensive mining activities from antiquity over several centuries . Today the zinc wall can be crossed on an educational tunnel path repaired by the PES . Based on the motorway tunnel , the zinc wall tunnel is often referred to as the "first Tauern tunnel".

Location and surroundings

The zinc wall is located on the Tauern main ridge in the western part of the Schladminger Tauern and separates the Styrian Obertal (municipality of Schladming ) from the Lungau and Salzburg Znachtal (municipality of Weißpriach ). The summit forms the center of a north-west-south-east running ridge that runs from the Vetterspitzen ( 2524 m ) to the Graunock ( 2477 m ). The zinc wall between Holzscharte (approx. 2360 m ) and Brettscharte ( 2236 m ) is bordered by the Knappenkar in the west, the Schnabelkar in the northeast and the Zinkenkarl in the southeast. There are several abandoned mining tunnels around the mountain , of which those through the zinc wall ( zinc wall tunnels ) have been prepared as show tunnels. The Keinsprechthütte ( 1,872 m ) to the northeast can serve as a base .

geology

The zinc wall and its surroundings belong to the Schladming crystalline complex of the lower eastern alpine blanket . The dominant rocks are migmatic paragneiss or mica schist with deposits of volcanic origin. The pyrite-rich shales are many places maroon up suspects and in mining as Branden called. On the zinc wall there are four clusters of burns and carbonate dikes . The occurrence of the nickel and cobalt ores relevant to mining is linked to them. The formation of the deposit goes back to hydrothermal influences ; By tearing open the metamorphic slate in the course of renewed mountain formation processes in the Tertiary , crevices formed perpendicular to the stratification through which carbonic acid , arsenic and metal-containing water could rise. The ore deposits along the clusters are spherical and not contiguous, which would have made mining much easier.

Due to the historical mining activity (see mining ), the mountain has long been the focus of geological and mineralogical interest. In 1874, for example, Johann Rumpf described the area's meddles . Many important finds are now abroad. In total, more than 70 different minerals were found on the zinc wall . In 1956 Fritz Pribitzer distinguished the following primary groups:

|

|

Mining

The zinc wall is part of a former mining area, which is referred to in the literature as zinc wall cousins (older than zinc wall vöttern ). In addition to the ore veins of the zinc wall, this included above all the Vetterkar. Numerous mouth holes and dilapidated miners' houses testify to centuries of mining activity. With regard to the mined raw materials, three periods can be distinguished for the zinc wall:

- Silver , copper and lead mining : until the 17th century

- Cobalt mining : early 17th century to 18th century

- Nickel mining : 1832–1875

The many tunnels that literally perforate the mountain cannot be precisely dated due to a lack of documents. The mining activity on the zinc wall has been historically established since the 13th century, but the oldest traces point to Celtic and Roman activities. The characteristic colors of the minerals obtained suggest that the mountain blessing of the area was already recognized in antiquity. In addition to the three main resources, gold and mercury were also briefly mined on the zinc wall . The zinc wall owes its name not to the metal of the same name , which was never mined on it, but to its characteristic shape, which is reminiscent of a prong or prong. The name Zinkenkogel can therefore also be read in old depictions .

Silver mining

Silver mining reached its heyday in the 16th century. In the process, silver-containing pale ores were primarily extracted in the silver crevice of the zinc wall. The nickel, arsenic and cobalt ores were not used at that time and they were disposed of in the dumps . At the height of the “silver fever”, around 1,500 miners were employed in 250 pits. Legends tell of the arrogance of the hardworking miners, which resulted in the drying up of the raw material sources as a punishment from God. Indeed, the discovery of America as well as inferior mining technology and falling gold and silver prices led to the decline of mining. The Schladming peasant and miners' uprising contributed the rest in 1525. The figure of the miner still adorns the coat of arms of the municipality of Schladming .

Cobalt mining

After 1700 the silver deposits became increasingly sparse and the focus was on the mining of cobalt ores, which were used in the form of smalts . As a fresh quarry, the minerals were difficult to distinguish from one another, which is why the debris was first stored in pits, where it was discolored by the influence of the atmosphere. In this way they sorted out the crimson cobalt ores and threw the rest on the heaps. From 1763 this happened under the care of Johann Eyselsberg. The cobalt ores were transported by axis to Gloggnitz and processed in the blue paint factory there, before sales difficulties for cobalt arose in 1816 and operations had to be stopped.

Nickel mining

The extraction of nickel began during the cobalt mining. After accumulating in an arsenic or sulfur compound (food), the nickel was obtained metallically through roasting processes . In 1832 the chemist Freiherr Johann Rudolf Ritter von Gersdorff (1782–1849) acquired the pits on and around the zinc wall and revitalized the previously closed mining. The sulphurous nickel ore gersdorffit he discovered was first described as a new mineral in 1847. The discovery of large nickel deposits in New Caledonia once again made mining in the Schladminger Tauern uncompetitive. The Vienna stock market crash in 1873 finally dealt the building with the fatal blow.

In the interwar period , mining was revitalized again for a short time, but it did not prove to be profitable. A large-scale geological survey by Gustav Hießleitner in 1929 showed that the deposits were largely exploited and that there was no potential for further prospecting .

Tourist development

Gallery trail

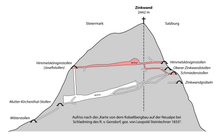

In 1984, the Schladming Cave Group of the PES established an educational trail with the Schladminger Rotary Club , which made it possible for hikers to cross the zinc wall for the first time. For a while, guided tours were offered through the mountain, the interior of which has already been compared to an Emmentaler . The tunnel educational path begins on the Lungau side with two information boards at the ruins of a miner's house. In the immediate vicinity is a several meter long snow collar made of dry stone , covered with wooden boards, providing avalanche-safe access to the wall. The entrance to the tunnel is through the former miner's forge . Then two steep steps, which are made accessible with ladders, have to be overcome and you reach the Himmelsköniginstollen , which crosses the mountain in its entirety. On the right-hand side you get to the reconstructed miner's room, which can serve as a bivouac in an emergency . A door leads to a lookout. The further way to the Styrian tunnel entrance is more or less straight past a wooden toilet block. Shortly before the exit, the passage reaches a narrow point that is easy to pass when crouched.

Crossing a tunnel from the Lungau side has the advantage that the ladders can be overcome on the ascent. A headlamp and, if necessary, a helmet are essential for the quarter-hour crossing . Orientation in the tunnel is made easier by signs.

Approach

The access to the zinc wall tunnel can be made either from the Keinsprechthütte (1 hour), from the Ignaz-Mattis-Hütte (2 hours) or from the Weißpriach Valley (3½ hours). All three climbs are unmarked and relatively arduous. From the Keinsprechthütte the ascent is steep through the so-called Knappenrinndl . The path from the Ignaz-Mattis-Hütte leads through the Vetterkar, from the Knappenseen without a path to the Vetterscharte (approx. 2420 m ) and gently descending into the Lungau through the Knappenkar (Knappenkarsee). The last ascent to the tunnel entrance is from the snow collar up steeply over an exposed ledge that is secured with a rope. In addition, a ladder has to be overcome.

Ascent to the summit

The summit cross on the zinc wall is rarely visited. The most common ascents are unmarked from the Holzscharte (access from the Styrian tunnel entrance) via the northwest ridge ( places I ) or from the Brettscharte via the east ridge ( I ). Expect 1½ hours from the Keinsprechthütte. A head for heights is essential to climb the summit.

photos

Literature and maps

- J. Avias & A. Bernard: Sur l'origine des gites de nickel et de la région de Zinkwand-Vöttern area (Austriche). Sciences de la Terre 11 (1996), pp. 375-383 (French).

- HW Fuchs: Ore microscopic and mineral chemical investigations of the ore deposits of Zinkwand-Vöttern in the Lower Tauern near Schladming. Archive for deposit research of the Federal Geological Institute 9 (1988), pp. 33–45.

- Gustav Hießleitner: The zinc wall-Vöttern nickel cobalt ore deposit in the Lower Tauern near Schladming. A geological and mining survey. In: Berg- und Hüttenmännisches Jahrbuch Volume 77, Issue 3 (1929), pp. 104–123.

- Sigmund Koritnig: Three arsenic pebbles with their parageneses from the zinc wall near Schladming. In: Joanneum, Mineralogisches Mitteilungsblatt 2 (1955), pp. 45-48.

- Fritz Pribitzer: The zinc wall mineral deposit near Schladming in Styria (Austria). In: Der Aufschluss, Vol. 7, Heft 3 (1956), pp. 60–62.

- Johann Rumpf: About Mispickel vom Leyerschlag in the zinc wall near Schladming. In: Mineralogische Mitteilungen, Heft III (1874), ges. von Tschermak , pp. 231-239.

- Freytag & Berndt Vienna , hiking map 1: 50,000, WK 201, Schladminger Tauern - Radstadt - Dachstein , ISBN 978-3850847162 .

- Freytag & Berndt Vienna, hiking map 1: 35,000, WK 5201, Schladming - Ramsau am Dachstein - Haus im Ennstal - Filzmoos - Stoderzinken , ISBN 978-3707910872 .

Web links

- The secrets of the zinc wall - hike from the Lungau side

- The first Tauern tunnel - hike from the Styrian side

- Round tour at Styria Alpin

- Zinc wall in the mineral atlas

Individual evidence

- ↑ Bernd Orfer: The first Tauern tunnel. In: The Standard . August 7, 2004, accessed September 19, 2016 .

- ↑ Digital Atlas of Styria: Geology & Geotechnics. State of Styria , accessed on December 26, 2016 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Fritz Pribitzer: The zinc wall mineral deposit near Schladming in Styria (Austria) . In: Der Aufschluss, Vol. 7 (1956), H. 3, pp. 59-62.

- ↑ Zinkwand-Vöttern. In: Mineralienatlas . Stefan Schorn, accessed on December 27, 2016 .

- ↑ a b c Adolf Longin: The zinc wall and its surroundings . In: Der Ennstaler, Wochenzeitung, issue of September 24, 1937 (vol. 32, no. 39), pp. 3–4.

- ↑ Gustav Hießleitner: The zinc wall-Vöttern nickel cobalt ore deposit in the Lower Tauern near Schladming. A geological and mining survey. In: Berg- und Hüttenmännisches Jahrbuch Volume 77, Issue 3 (1929), pp. 104–123.

- ↑ ÖAV-Zinc Wall-Vöttern tunnel educational trail. In: Mitteilungen 1984. Graz Academic Section of the Austrian Alpine Association , Graz 1985, p. 45. [1] (PDF; 33 MB), accessed on December 31, 2016

- ↑ Günter and Luise Auferbauer: hike paradise Styria. All 2000s from Dachstein to Koralpe. Styria , Graz 2000, p. 212. ISBN 3-222-12783-2 .