History of Montreal

The human history of Montreal, located in Quebec, Canada, spans some 8,000 years and started with the Algonquin, Huron, and Iroquois tribes of North America. Jacques Cartier became the first European to reach the area now known as Montreal in 1535 when he entered the village of Hochelega on the Island of Montreal while in search of a passage to Asia during the Great Explorations. Seventy years later, Samuel de Champlain unsuccessfully tried to create a fur trading post but the local Iroquois defended their land. A mission named Ville Marie was built in 1642 as part of a project to create a French colonial empire. Ville Marie became a centre for the fur trade and French expansion into New France until 1760, when it was surrendered to the British army, following the defeat of the Battle of the Plains of Abraham. British immigration expanded the city and the city's golden era of fur trading began with the advent of the locally-owned North West Company.

Montreal was incorporated as a city in 1832. The city's growth was spurred by the opening of the Lachine Canal and Montreal was the capital of the United Province of Canada from 1844 to 1849. Growth continued and by 1860 Montreal was the largest city in British North America and the undisputed economic and cultural centre of Canada. Annexation of neighbouring towns between 1883 and 1918 changed Montreal back to a mostly Francophone city. During the 1920s and 1930s the Prohibition movement in the United States turned Montreal into a haven for Americans looking for alcohol. As with the rest of the world, the Great Depression brought unemployment to the city but this waned in the mid 1930s and skyscrapers began to be built.

World War II brought protests against conscription and caused the Conscription Crisis of 1944. Montreal's population surpassed one million in the early 1950s. A new metro system was added, Montreal's harbour was expanded and the St. Lawrence Seaway was opened during this time. More skyscrapers were built along with museums. International status was cemented by Expo 67 and the 1976 Summer Olympics. A major league baseball team, called the Montreal Expos started playing in Montreal in 1969 but the team moved to Washington, DC to become the Washington Nationals in 2005. Montreal now constitutes one of the regions of Quebec.

The Village of Ville-Marie

The area known today as Montreal had been inhabited by the Algonquin, Huron, and Iroquois for some 8,000 years, while the oldest known artifact found in Montreal proper is about 4,000 years old. The first European to reach the area was Jacques Cartier on October 2, 1535. Seventy years after Cartier, Samuel de Champlain went to Hochelaga but the village no longer existed. He decided to establish a fur trading post at Place Royal on the Island of Montreal, but the local Iroquois successfully defended their land. It was not until 1639 that a permanent settlement was created on the Island of Montreal by a French tax collector named Jérôme Le Royer. Under the authority of the Roman Catholic Société Notre-Dame, missionaries Paul Chomedey de Maisonneuve, Jeanne Mance and a few French colonists set up a mission named Ville Marie on May 17, 1642 as part of a project to create a colony dedicated to the Virgin Mary. Jeanne Mance founded the Hôtel-Dieu, the first hospital in North America, in 1644. On January 4th, 1648, Governor Paul Chomedey de Maisonneuve granted Pierre Gadois (who was in his fifties) the first concession of land - some 40 acres. In November of 1653, another 140 individuals arrived to enlarge the settlement that eventually became known as Montréal.

Ville Marie would become a centre for the fur trade,The town was fortified in 1725 and remained French until 1760, when, during the French and Indian War, Pierre François de Rigaud, Marquis de Vaudreuil-Cavagnal surrendered it to the British army under Jeffrey Amherst. Fire destroyed one quarter of the town on May 18, 1765. A few buildings from this era remain in the area known today as Old Montreal and in a few places around the island.

Now a British colony, and with immigration no longer limited to members of the Roman Catholic religion, the city began to grow from British immigration. In 1775, American Revolutionists briefly held the city but soon left when it became apparent that they could not take and hold Canada. More and more English-speaking merchants continued to arrive in what had by then become known as Montreal and soon the main language of commerce in the city was English. The golden era of fur trading began in the city with the advent of the locally-owned North West Company, the main rival to the primarily British Hudson's Bay Company.

The town remained populated by a majority of Francophones until around the 1830s. From the 1830s, to about 1865, it was inhabited by a majority of Anglophones, most of recent immigration from the British Isles or other parts of British North America.

It was also Scots who constructed Montreal's first bridge across the Saint Lawrence River and who founded many of the city's great industries, including Morgan's, the first department store in Canada, incorporated within the Hudson's Bay Company in the 1970's; the Bank of Montreal; Redpath Sugar; and both of Canada's national railroads. The city boomed as railways were built to New England, Toronto, and the west, and factories were established along the Lachine Canal. Many buildings from this time period are concentrated in the area known today as Old Montreal. Noted for their philanthropic work, Scots established and funded numerous Montreal institutions such as McGill University, the Literary and Historical Society of Quebec and the Royal Victoria Hospital.

The City of Montreal

Montreal was incorporated as a city in 1832. The city's growth was spurred by the opening of the Lachine Canal, which permitted ships to pass by the unnavigable Lachine Rapids south of the island. Montreal was the capital of the United Province of Canada from 1844 to 1849, bringing even more English-speaking immigrants: Late Loyalists, Irish, Scottish, and English. Riots led by the Anglophone community led to the burning of the Canadian Parliament, forcing the Empire to choose another city to represent the capital of its colony. On a more positive note, the Anglophone community built one of Canada's first universities, McGill, and the wealthy built large mansions at the foot of Mont Royal. The economic boom also attracted thousands of immigrants from Italy, Russia, Eastern Europe, and other parts of French Canada.

In 1852, Montreal had 58,000 inhabitants and by 1860, Montreal was the largest city in British North America and the undisputed economic and cultural centre of Canada. From 1861 to the Great Depression of 1930, Montreal went through what some historians call its Golden Age. St. James Street became the most important economic centre of the Dominion of Canada. The Canadian Pacific Railway made its headquarters there in 1880, and the Canadian National Railway in 1919. At the time of its construction in 1928, the new head office of the Royal Bank of Canada at 360 St. James Street was the tallest building in the British Empire. With the annexation of neighbouring towns between 1883 and 1918, Montreal became a mostly Francophone city again. The tradition of alternating between a francophone and an anglophone mayor thus began, and lasted until 1914.

War and the Great Depression

Montrealers volunteered to serve in the army to defend Canada during World War I, but most French Montrealers opposed mandatory conscription. After the war, the Prohibition movement in the United States turned Montreal into a haven for Americans looking for alcohol. Americans would go to Montreal for drinking, gambling, and prostitution, which earned the city the nickname "Sin City." Despite the increase in tourism, unemployment remained high in the city, and was exacerbated by the Stock Market Crash of 1929 and the Great Depression. However, Canada began to recover from the Great Depression in the mid 1930s, and real estate developers began to build skyscrapers, changing Montreal's skyline. The Sun Life Building, built in 1931, was for a time the tallest building in the Commonwealth. During World War II its vaults were the secret hiding place of the gold bullion of the Bank of England and the British Crown Jewels.

Canada could not escape World War II. Mayor Camillien Houde protested against conscription. He urged Montrealers to ignore the federal government's registry of all men and women because he believed it would lead to conscription. Ottawa, considering Houde's actions treasonable, put him in a prison camp for over four years, from 1940, until 1944, when the government was forced to institute conscription (see Conscription Crisis of 1944).

Merger and demerger

The idea of uniting the island of Montreal under one municipal government was first proposed by Jean Drapeau in the 1960s. The idea was strongly opposed in many suburbs, although three towns (Rivière des Prairies, Saraguay and Saint-Michel) were annexed to Montreal between 1963 and 1968. Pointe-aux-Trembles was annexed in 1982.

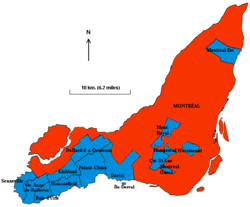

In 2001, the provincial government announced a plan to merge major cities with their suburbs. As of January 1, 2002, the entire Island of Montreal, home to 1.8 million people, as well as the several outlying islands that were also part of the Montreal Urban Community, were merged into a new "megacity". Some 27 suburbs as well as the former city were folded into several boroughs, named after their former cities or (in the case of parts of the former Montreal) districts.

During the 2003 provincial elections, the winning Liberal Party had promised to submit the mergers to referendums. On June 20, 2004, a number of the former cities voted to demerge from Montreal and regain their municipal status, although not with all the powers they once had. Baie-d'Urfé, Beaconsfield, Côte-Saint-Luc, Dollard-des-Ormeaux, Dorval, Hampstead, Kirkland, L'Île-Dorval, Montreal East, Montreal West, Mount Royal, Pointe-Claire, Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue, Senneville, and Westmount voted to demerge. The demergers came into effect on January 1, 2006.

Anjou, LaSalle, L'Île-Bizard, Pierrefonds, Roxboro, Sainte-Geneviève, and Saint-Laurent had a majority in favour of demerger, but the turnout was insufficient to permit demerger, so those former municipalities will remain part of Montreal. No referendum was held in Lachine, Montreal north, Outremont, Saint Leonard, or Verdun - nor in any of the boroughs that were part of the former city of Montreal.

Until 2001, the Island of Montreal was divided into 28 municipalities: the city of Montreal proper and 27 independent municipalities. On January 1, 2002, the 27 independent municipalities of the island of Montreal were merged with the city of Montreal, under the slogan: "Une île, une ville" ("One island, one city"). This merger was part of a larger provincial scheme launched by the Parti Québécois across Quebec, resulting in the mergers of many municipalities. Government claimed that larger municipalities were more efficient, and more able to withstand competition with other cities in Canada which had already expanded their territory in the late 1990s, such as Toronto and Ottawa.

As elsewhere in Canada, city mergers across Quebec were bitterly contested by a significant part of the population, especially on the Island of Montreal. One point of contention was that there was no public consultation. The situation on the island was complicated by the differences between predominantly English-speaking municipalities and the predominantly French-speaking city of Montreal. Many in these suburbs believed a merger would deprive them of their rights and reduce the quality of services, despite claims by the mayor of Montreal that linguistic rights would remain protected in the new city of Montreal. Many street protests were organized and lawsuits were filed. 15 municipalities appealed to the Court of Appeal of Quebec but failed to halt the merger. At the 2001 census, the city of Montreal (185.94 km²/71.8 square miles) had 1,039,534 inhabitants. After the merger, the population of the new city of Montreal (500.05 km²/193.1 square miles) was 1,812,723 (based on 2001 census figures). For comparison, in 2001 the city of Toronto (629.91 km²/243.2 square miles) had 2,481,494 inhabitants.

The merged city of Montreal was divided into 27 boroughs (known in French as "arrondissements") in charge of local administration, while the city above them was responsible for larger matters such as economic development and transportation issues. It is only a coincidence that there were 27 independent municipalities before 2002, and 27 boroughs after the merger. Although some boroughs corresponded to the former municipalities, in many cases smaller municipalities were combined into a single borough.

In the provincial election of April 2003, the Liberal Party defeated the Parti Québécois. One central promise during their campaign was that they would allow merged municipalities across the province to organize referendums in order to demerge if they wished to do so. On June 20, 2004, referendums were held throughout Quebec. On the Island of Montreal, referendums were held in 22 of the 27 previously independent municipalities. Following the referendum results, 15 of the previously independent municipalities recovered their independence on January 1, 2006. These are predominantly English-speaking municipalities, in addition to a few French-speaking municipalities. One of the 15 municipalities to be recreated, L'Île-Dorval, had no permanent inhabitants at the 2001 census.

The demerger took place on January 1, 2006, and there are now 16 municipalities on the Island of Montreal (the city of Montreal proper plus 15 independent municipalities). The post-demerger city of Montreal (divided into 19 boroughs) has a territory of 366.02 km² (141.3 square miles) and a population of 1,583,590 inhabitants (based on 2001 census figures). Compared with the pre-merger city of Montreal, this is a net increase of 96.8% in land area, and 52.3% in population.

The city of Montreal still has almost as many inhabitants as the old unified city of Montreal (the suburban municipalities now recreated are less densely populated than the core city), even though population growth will be slower for some time. They also say that the overwhelming majority of industrial sites are now located on the territory of the post-demerger city of Montreal. Nonetheless, the post-demerger city of Montreal is only about half the size of the post-1998 merger city of Toronto (both in terms of land area and population).

However, it should be noted that the 15 recreated municipalities do not have as many powers as they did before the merger. Many powers remain with a joint board covering the entire Island of Montreal, in which the city of Montreal has the upper hand.

Despite the demerger referendums held in 2004, the controversy continues, with politicians focusing on the cost of demerging. Several studies show that the recreated municipalities will incur substantial financial costs, thus forcing them to increase taxes (which is a startling prospect in the generally wealthier demerging English-speaking municipalities). Proponents of the demergers contest these surveys, and point to reports from other merged municipalities across the country that show that contrary to their primary raison d'être, the fiscal and societal costs of mega-municipalities far exceed any imagined benefit.

Origin of the name

Montreal was named for the Island of Montreal, which in turn was named for Mount Royal.

It is not certain how the name changed from Mont Royal to Mont Réal. Although pronounced differently in modern European French, however, "royal" and "réal" were and still are near rhymes in Québec French--which may explain the spelling in part. In 1556, Italian geographer G.B. Ramusio translated Mont Royal to Monte Reale in a map. In 1575, François de Belleforest became the first to write Montreal, writing:

- … au milieu de la compaigne est le village, ou Cité royale iointe à vne montaigne cultivée, laquelle ville les Chrestiens appellerent Montreal…

- "In the middle of the field is the village or royal colony near a cultivated mountain. Christians call this town Montreal."

During the early 18th century, the name of the island came to be used as the name of the town. Two 1744 maps by Nicolas Bellin name the island Isle de Montreal and the town, Ville-Marie; but a 1726 map refers to the town as "la ville de Montréal." The name Ville-Marie soon fell into disuse to refer to the town, though today it is used to refer to the Montreal borough that includes downtown.

In the modern Iroquois language, Montreal is called Tiohtià:ke. Other native languages, such as Algonquin, refer to it as Moniang. [1]

See also

- Boroughs of Montreal

- Districts of Montreal

- Montreal

- Montreal Merger

- Municipal reorganization in Quebec

- Toronto-Montreal rivalry