All-Ukrainian Association "Svoboda"

| All-Ukrainian Association "Svoboda" | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Party leader | Oleh Tjahnybok |

| founding | 1991 / 1995 |

| Headquarters | 17 Velyka Zhytomyrska Street, Kiev , Ukraine |

| Alignment | Right-wing extremism |

| Colours) | yellow and blue |

| Parliament seats |

1/450 |

| Number of members | 15,000 |

| European party | Alliance of European National Movements (2009-2014) |

| Website | svoboda.org.ua/ |

The all -Ukrainian association "Swoboda" ( Ukrainian Всеукраїнське об'єднання "Свобода" , German for short freedom ) is a Ukrainian right-wing radical and radical nationalist party, aiming at an ethnic Ukrainian identity . The party sees its origin in the Organization of Independent Nationalists (OUN) and its partisan army UPA . Svoboda also worships Stepan Bandera and sees itself in opposition to "Russian imperialism" with which the sovereignty of Ukraine is confronted "in the past and present". Their party leader is Oleh Tjahnybok .

In 2014, the party was involved in the interim government of Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk .

history

The party was founded in 1991 but was not officially registered until 1995. It emerged from an association of student brotherhoods, local national Ukrainian associations and Afghanistan veterans. The chairman was Yaroslaw Andruschkiw from 1991 to 2004 . Until February 2004 it had the name Social-National Party of Ukraine , which should allude to the National Socialist German Workers' Party . In order to become more politically acceptable, it was reformed by the new chairman Oleh Tjahnybok and took the name Swoboda ( freedom ); various neo-Nazi groups were also excluded from the party.

Since 2009 Swoboda has had observer status in the Alliance of European National Movements , which also includes the Hungarian Jobbik and the British National Party . In March 2014, the party withdrew from this alliance after some member parties, including the French National Front , expressed their approval of the incorporation of Crimea into the Russian Federation.

After nationalist youths insulted war veterans in Lviv on May 9, 2011 and denied access to the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier for visitors wearing Russian or Soviet Georgian ribbons , the government blamed the Swoboda Party for the riots . As a result, a debate arose over a possible ban on the party.

In February 2012, Svoboda spokesman Yuriy Syrotiuk complained that Ukraine was represented at the Eurovision Song Contest by the singer Gaitana . According to Syrotiuk, she is “not an organic representative of Ukrainian culture” because her father is Congolese .

In December 2012, Svoboda's party leader Tjahnybok and his deputy Ihor Miroshnychenko from the Simon Wiesenthal Center were ranked 5th in their “ Top Ten Anti-Semitic / Anti-Israel Slurs ”. Tjahnybok had claimed that Ukraine was ruled by a Russian-Jewish mafia ( москальско-жидівська мафія ), and Miroshnychenko used the anti-Semitic swear word Schydowka ( Жидовка ) to refer to actress Mila Kunis .

In the same month, Swoboda representatives visited the NPD parliamentary group in the Saxon state parliament .

In August 2013, the Swoboda party founded an offshoot in Munich. The party also has its own cells in Frankfurt am Main and Cologne , which consist mainly of Ukrainian students.

In July 2013, 30 Israeli Knesset members signed an open letter addressed to the President of the European Parliament, Martin Schulz ( SPD ). In it, they warned of the party's anti-Semitism and Russophobia and criticized the fact that the two largest opposition parties in Ukraine were working with it.

In October 2013, the party organized a demonstration in Kiev to campaign for the UPA's actions to be recognized as a struggle for national liberation and for Stepan Bandera and Roman Shukhevich's judicial revocation of the title “Hero of Ukraine” to be withdrawn.

Swoboda's role during the Euromaidan

With the beginning of the protests in Ukraine in 2013 , Svoboda formed an oppositional three-way alliance with the UDAR of Vitali Klitschko and the All-Ukrainian Association "Fatherland" of Yulia Tymoshenko with the aim of removing the Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych . Swoboda party leader Tjahnybok said in this regard that the opposition would build a tent city on the Majdan (Independence Square) and start a nationwide strike with which the alliance would force new elections.

The EU ambassador to Ukraine, Jan Tombinski, described Swoboda in an interview on December 21, 2013 as an “equal partner for talks with the EU”. The party supports Ukraine's rapprochement with the EU. Swoboda must, however, note that “nationalistic and xenophobic content has no place in modern Europe”.

Role of the party since the resignation of Yanukovych

When the government was formed on February 27, 2014 after the overthrow of Yanukovych, the deputy chairman of the Svoboda party, Oleksandr Sych , was appointed deputy prime minister. The party placed three more members of the transitional government that year. Oleh Machnitskyj got the post of General Prosecutor .

On the evening of March 18, 2014, a group of members of parliament and supporters of “Svoboda” led by Ihor Miroshnychenko (he is deputy chairman of the “Ukrainian Committee for Freedom of Expression”) penetrated the Kiev office of the head of the state television broadcaster Natsionalna Telekompanija Ukraïny , Olexandr Pantelejmonov, and forced him to sign a resignation letter with threats and bumps. They accused him of being unsuitable for supporting Russian "hostile" propaganda. The broadcaster had shown excerpts from Vladimir Putin's speech on the accession of Crimea on March 18, 2014 , in which he welcomed the result of the controversial referendum for the annexation of the Republic of Crimea to Russia. Interim Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk condemned the action.

With the more radical Prawyj sector ("Right Sector"), which emerged in the course of the Euromaidan, under the leadership of Dmytro Jarosch , the party received competition from the far-right fringe, but it works partly with it. At the same time, Jarosch describes the Svoboda party as "too liberal".

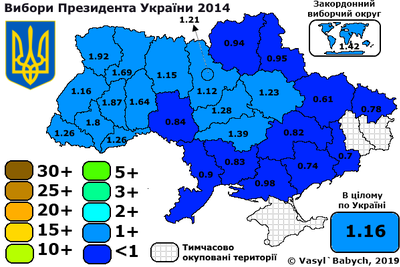

In the 2014 presidential election in Ukraine , 1.16 percent of voters across the country voted for Oleh Tjahnybok , the party leader and candidate of Svoboda.

In the course of the war in eastern Ukraine , the party set up its own combat unit, the "Sitsch" battalion, which fights against pro-Russian separatists. The term Sitsch goes back to the Zaporozhian Cossacks .

In the 2019 parliamentary elections, Swoboda joined an electoral alliance of various nationalist organizations and, with 2.4 percent, clearly failed the five percent hurdle, but was able to win a mandate.

Classification from outside

The party is also classified variously as right-wing extremist , neo-fascist or neo-Nazi and anti-Semitic .

In a resolution dated December 13, 2012, the EU Parliament expressed its concern about an “increasing nationalist mood in Ukraine”, which was expressed in Svoboda's electoral success. “Racist, anti-Semitic and xenophobic views” would contradict the basic values of the EU. Parliament appealed to the “democratically-minded parties in the Verkhovna Rada” not to associate with Svoboda, not to support the party and not to form coalitions with it.

In December 2012, Tjahnybok denied that Swoboda was an anti-Semitic party or that there was anti-Semitism in his party. In January 2013, a Svoboda spokesman stated that it was not an anti-Semitic party and that Jews in Ukraine had nothing to fear. Likewise, every ethnic minority has the right to participate in government.

In August 2013, in response to a small question from the Die Linke parliamentary group, the German government stated that Swoboda was assessed as a right-wing populist and nationalist party, some of which represented right-wing extremist positions. In the Ukrainian parliament she is currently not showing any obvious right-wing extremist tendencies in parliamentary work. In the run-up to the parliamentary elections in 2012, the party revised its election program and removed right-wing extremist statements. The German ambassador to the Ukraine met the chairman of the party on April 29, 2013 for an interview, during which the ambassador stated that "anti-Semitic statements are unacceptable from a German perspective".

The Polish political scientist Tadeusz A. Olszański gave in July 2011 the assessment that radical neo-Nazi and racist groups (English: "radical neo-Nazi and racist groups") had been excluded from the party. In May 2013, the World Jewish Congress classified Svoboda as neo-Nazi and called for the party to be banned. The Briton Robin Shepherd of the Henry Jackson Society saw a 2013 report by the World Jewish Congress on neo-Nazi parties in Europe as having a neo-Nazi component in the ideology of the Svoboda party. This is most clearly represented by the parliamentarian Yuri Michaltschischin . The spectrum of the party's electorate classified an article published by the World Jewish Congress that year as reaching from neo-Nazis to a weary mainstream.

According to an analysis by the Konrad Adenauer Foundation, party leader Tjahnybok is mobilizing " anti-Semitic resentment, xenophobia and Ukrainian isolationism ". He expresses himself "decidedly anti-Russian and at the same time anti-western and thus meets moods that are prevalent in some regions of western Ukraine ."

In March 2014, the Svoboda party was banned in Crimea .

In June 2014, a German lawyer filed on behalf of Tjahnybok in Berlin public prosecutor complaint for libel and slander against the leader of the party The Left , Gregor Gysi . Gysi made various statements both in the Bundestag ("I'm quoting now. You have to listen to what he said literally: 'Grab your guns. Fight the Russian pigs, the Germans, the Jewish pigs and other bad habits'") as well as in a talk show of the ZDF the honor of Tjahnybok "personally seriously injured". Gysi explained, among other things, that there are enough indications, statements and behavior of this party to justify a characterization as "fascist".

Program

The all-Ukrainian association “Svoboda” describes its party ideology in its programs as “social nationalism” and ties in with the concept of “natiocracy” formulated by the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) in the 1930s. The nationalist politician Stepan Bandera and the leader of the Wehrmacht Legion "Nightingale" Roman Schuchewytsch are venerated by "Swoboda" as national heroes: In Lvov, for example, on an initiative of Swoboda members of parliament, the former "Road of Peace" is now after the "Nightingale Battalion" named. A campaign of the party is aiming for the name of Lviv airport to be named "Stepan Bandera". Bandera is regularly honored in torchlight procession with several thousands of party supporters. In addition, the Swoboda party is committed to honoring the 14th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (Galician No. 1) .

Swoboda demands the introduction of the feature "ethnic affiliation" in the identity card as well as ethnic quotas when filling positions in politics, administration and business. The party blames an "anti-Ukrainian political elite" for the cultural, political and economic decline of Ukraine. Swoboda repeatedly uses the term "anti-Ukrainian activity", which should be included as a criminal offense in Ukrainian legislation and punished with prison terms.

In her election manifestos and the programmatic statements of her candidate for the 2010 presidential election in Ukraine , Svoboda called, among other things, for the abolition of the autonomy of Crimea , the abolition of the special status of Sevastopol, a program for the integration of Crimea into the Ukrainian state, and the creation of checkpoints at all military bases leased to Russia, the hoisting of the Ukrainian flag over all leased bases and the termination of the Kharkiv Agreement of April 21, 2010, which extended the lease for Russia's Black Sea fleet from 2017 to 2042. In the event that Russia had not withdrawn its fleet in 2017, unilateral actions should be prepared in the National Security Council.

In terms of immigration policy, she demands, among other things, the inadmissibility of dual citizenship and preferential conditions for the return of ethnic Ukrainians from emigration . On the other hand, the immigration stop of non-Ukrainians is called for, although there is de facto no immigration to Ukraine today.

In terms of foreign policy, the party supports the withdrawal from all “Eurasian alliances with a center in Moscow”, especially the CIS , the creation of a Baltic - Black Sea axis, the status of a nuclear power for Ukraine and the country's accession to NATO .

In terms of economic policy, all strategic companies are to be transferred to state ownership and imported products are to be replaced by goods from Ukrainian production. It also calls for a ban on the advertising of tobacco products and alcohol, as well as criminal responsibility for the propagation of drug use and “sexual perversions”.

Election results

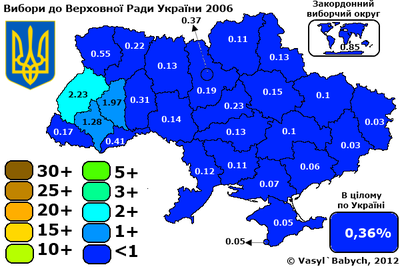

The party ran for the parliamentary elections in 2006 and 2007 , but with 0.36 and 0.76% nationwide, it clearly missed the number of votes required for a parliamentary seat. In the 2012 parliamentary election , the party achieved a surprisingly high result with 10.4% of the vote. With this she moved into the Verkhovna Rada for the first time with 37 mandates ; Tjahnybok became chairman of the parliamentary group. In the 2014 parliamentary election , she only achieved 4.71% and thus missed the 5% hurdle, but was able to win 6 direct mandates. Chairman Tjahnybok himself missed the re-entry.

The party always got the highest percentage of votes in western Ukraine , especially in eastern Galicia. She was able to send representatives to the regional and city parliaments of Lviv , Ternopil and Ivano-Frankivsk in the local elections . It also provides some mayors in municipalities. In the early regional elections in the Ternopil area on March 15, 2009, “Svoboda” received 35 percent of the votes and won 50 of the 120 seats in the regional parliament. Critics accused the Yanukovych government of specifically supporting "Svoboda" in order to draw votes from other opposition parties in this way. In the 2010 presidential election , party leader Tjahnybok achieved 1.43% of the vote.

Web links

literature

- Tadeusz A. Olszański: Svoboda Party - The New Phenomenon on the Ukrainian Right-Wing Scene. OSW Commentary No. 56, Center for Eastern Studies (OSW), Warsaw 2011.

- Per Anders Rudling: The Return of the Ukrainian Far Right. The Case of VO Svoboda. In Ruth Wodak , John E. Richardson (Eds.): Analyzing Fascist Discourse. European Fascism in Talk and Text. Routledge, New York / Abingdon 2013, pp. 228–255.

- Anton Shekhovtsov: The Creeping Resurgence of the Ukrainian Radical Right? The Case of the Freedom Party. In: Europe-Asia Studies , Volume 63, No. 2, 2011, doi : 10.1080 / 09668136.2011.547696

- Anton Schechowzow, Andreas Umland : The belated rise of Ukrainophonic right-wing radicalism in post-Soviet Ukraine. In: Ukraine News , October 28, 2012. Part I: On the emergence of Ukrainian partisan ultra-nationalism in the 1990s. Part II: On the transformation of partisan Ukrainian ultra-nationalism in the years 2002-2012.

- Andreas Umland: A typical variety of European right-wing radicalism? Three peculiarities of the Ukrainian Freedom Party from a comparative perspective. In: Ukraine Analysis , No. 117, Federal Agency for Civic Education, May 28, 2013.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Всеукраїнське об'єднання "Свобода" - Історія ( Memento from January 8, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Analysis: The emergence of ukrainophone party-like right-wing extremism in Ukraine in the 1990s In: Federal Agency for Political Education, accessed on May 23, 2019

- ↑ Federal Agency for Civic Education: Analysis: The emergence of ukrainophonic party-like right-wing extremism in Ukraine in the 1990s | bpb. Retrieved June 4, 2018 .

- ^ The opposition in Ukraine is sorting itself out ( Memento from December 2, 2013 in the Internet Archive ), website of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung from June 19, 2013

- ^ A b Paul Sonne, James Marson: Nationalists Prove Tricky for New Ukraine Government. Party Derided as Fascist by Moscow Comes Under Fire After Members Assault TV Chief. Wall Street Journal , March 19, 2014, accessed March 20, 2014 (Above all, the party promotes an ethnic Ukrainian identity and battles what its members call Russian imperialism - and on the television incident: "At the moment there is war. I didn't beat him, I grabbed him by the hand and sat him down, "he told reporters in Kiev, describing" enemy propaganda "as treason.).

- ↑ Three peculiarities of the Ukrainian Freedom Party from a comparative perspective Federal Agency for Political Education June 3, 2013: The real external threat to Ukraine

- ↑ a b c Ingmar Bredies: Alarming dress rehearsal for the presidential elections. The regional election in Ternopil. (PDF; 876 kB)

- ↑ Oleh Tiahnybok withdraws Svoboda's membership within the Alliance of European National Movements ( Memento of 21 March 2014 Internet Archive ), the party's website from March 20, 2014

- ↑ Panel discussion: "Nationalism and Xenophobia in Yanukovych's Ukraine", February 19, 2013, Berlin - Ukraine-Nachrichten . ( ukraine-nachrichten.de [accessed June 4, 2018]).

- ↑ Ukrainian Prime Minister Azarov does not rule out a ban on the Svoboda party

- ↑ a b c d e Palash Gosh: Svoboda: The Rising Specter Of Neo-Nazism In The Ukraine in: International Business Times , December 27, 2012.

- ↑ 2012 Top Ten Anti-Israel / Anti-Semitic Slurs: Mainstream Anti-Semitism Threatens World Peace ( Memento from December 21, 2013 in the Internet Archive ), Simon Wiesenthal Center (December 27, 2012).

- ^ Website of the Konrad Adenauer Foundation from June 19, 2013 ( Memento from December 2, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ August 25, 2013: The Ukrainian ultra-nationalist party "Swoboda" ("Freedom") founds a party cell in Munich ( Memento from September 21, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Roman Danyluk: KIEV INDEPENDENCE SQUARE - history and background of the movement on the Maidan. Edition AV, Lich 2014, ISBN 978-3-86841-106-5 . Page 73

- ↑ a b Israeli Knesset sign protest letter against anti-Semitism and Russophobia in Ukraine in: Voice of Russia , July 9, 2013.

- ↑ Svoboda will take 20 thousand people to the streets and will demand return of the title to Bandera. Communists demand that the whole truth about the “heroes of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army” is told ( Memento from March 26, 2014 in the Internet Archive ), Kharkov News Agency on October 17, 2013

- ^ A b First success for the opposition in: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , December 2, 2013.

- ↑ a b Protests against the government in Ukraine. Vitali Klitschko calls on protesters to hold out in: RP Online , December 2, 2013.

- ↑ ( Page no longer available , search in web archives: Interview with the EU ambassador to Ukraine ), Focus from December 21, 2013

- ^ Upheaval in Ukraine - The new men and women of Kiev , FAZ of February 27, 2014

- ↑ Svoboda MPs: Attack on TV boss in Ukraine . Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, March 19, 2014

- ^ "Svoboda" deputies made "First national" channal director resign ( memento from March 19, 2014 in the Internet Archive ), Kharkov News Agency on March 18, 2014

- ↑ Crimean Crisis The Fatal Mistakes of the Kiev Government.

- ↑ Ukraine crisis: Key players In: BBC NEWS, accessed on May 23, 2019

- ↑ Партія Свобода створює власний батальйон In: ua.korrespondent.net, accessed on May 23, 2019

- ^ Anton Maegerle : Nationalist tones in: Blick nach Rechts , December 20, 2013.

- ^ Shekhovtsov, Anton (2011). The Creeping Resurgence of the Ukrainian Radical Right? The Case of the Freedom Party . Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 63, pp. 203-228.

- ↑ Taras Kuzio : Populism in Ukraine in a Comparative European Context Problems of Post-Communism, Vol. 57, p. 15.

- ↑ Rudling, Per Anders (2012), Anti-Semitism and the Extreme Right in Contemporary Ukraine , Mapping the Extreme Right in Contemporary Europe: From Local to Transnational (Routledge), p. 200.

- ↑ Bojcun, Marko (2012), The Socioeconomic and Political Outcomes of Global Financial Crisis in Ukraine , Socioeconomic Outcomes of the Global Financial Crisis: Theoretical Discussion and Empirical Case Studies (Routledge), p. 151.

- ↑ Alexei I. Miller: Тень «Свободы». expert.ru, November 9, 2012, accessed March 4, 2014 .

- ^ John Batchelor: Ultranationalist neo-Nazi parties on the march in Ukraine. Al Jazeera America , February 25, 2014, accessed March 4, 2014 .

- ↑ Rachel Hirshfeld: Clinton Indirectly Legitimizing Ukrainian Neo-Nazi Party? Arutz Scheva , November 6, 2012, accessed March 4, 2014 .

- ↑ Pawel Dulman: Память обезглавили. Rossiyskaya Gazeta , January 14, 2014, accessed March 4, 2014 .

- ↑ Sam Sokol: Jewish groups 'deeply concerned' over Ukraine. The Jerusalem Post , February 19, 2014, accessed March 4, 2014 .

- ↑ Anshel Pfeffer: Revolution unleashes new fears in Kiev. The Jewish Chronicle, February 27, 2014, accessed March 4, 2014 .

- ^ Seumas Milne: In Ukraine, fascists, oligarchs and western expansion are at the heart of the crisis. The Guardian , January 29, 2014, accessed March 4, 2014 .

- ↑ Resolution of the European Parliament of December 13, 2012 on the situation in Ukraine

- ↑ Tiahnybok denies anti-Semitism in Svoboda , Kyiv Post of December 27, 2012

- ↑ Ukraine party attempts to lose anti-Semitic image In: jpost.com, Retrieved May 23, 2019

- ↑ Answer of the Federal Government to the minor question from the DIE LINKE parliamentary group of August 22, 2013

- ^ Tadeusz A. Olszański: Svoboda Party - The New Phenomenon on the Ukrainian Right-Wing Scene . In: Center for Eastern Studies (Ed.): OSW Commentary . No. 56 , 2011 ( online ).

- ↑ The World Jewish Congress attributed "Swoboda" to the neo-Nazi parties ( Memento of December 22, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) in: Ukrinform (May 14, 2013).

- ↑ Sam Sokol: Ukrainian Jews split on dangers of protest movement in: The Jerusalem Post (December 4, 2013).

- ^ Robin Shepherd: Update on neo-Nazi political parties in Europe. World Jewish Congress , archived from the original on March 20, 2014 ; accessed on March 20, 2014 .

- ↑ Ukrainian far-right party upstages FIFA with visit to Zurich headquarters. World Jewish Congress , October 28, 2013, accessed March 20, 2014 .

- ↑ Election Handbook Ukraine 2010 (PDF; 701 kB) of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung p. 53

- ^ Crimea prohibits »Right Sector« In: neue-deutschland.de, accessed on May 23, 2019

- ^ Swoboda nationalists report Gysi , Der Tagesspiegel of June 16, 2014

- ↑ Fascists as role models. fr-online.de from March 12, 2014.

- ↑ a b Is the US backing neo-Nazis in Ukraine? Salon, accessed March 24, 2014

- ↑ 15,000 Ukraine nationalists march for divisive Bandera. USA Today

- ↑ What is behind the Swoboda party In: Das Erste, Retrieved on May 23, 2019

- ↑ Archived copy ( Memento from March 20, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Tadeusz A. Olszański: "Svoboda Party - The New Phenomenon on the Ukrainian Right-Wing Scene" , in: Center for Eastern Studies, July 4, 2011.

- ↑ Election Handbook Ukraine 2010 (PDF; 701 kB) of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung p. 72/73

- ^ Website of the Central Election Commission for the 2012 parliamentary election ( Memento from October 30, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ The Belated Rise of Ukrainophonic Right-Wing Radicalism in Post-Soviet Ukraine , from Ukraine News, October 28, 2012

- ↑ Article in Die Welt from December 9, 2013