Berlin blockade

The Berlin Blockade (First Berlin Crisis) is the name given to the blockade of West Berlin by the Soviet Union from June 24, 1948 to May 12, 1949. As a result of this blockade, the Western Allies could no longer supply West Berlin, which was an enclave in the Soviet occupation zone (SBZ), via land and water connections. The blockade was a means of exerting pressure on the Soviet side with the aim of finally integrating Germany into its own economic and political system via West Berlin, corresponded to a strategy developed by the Soviet side months earlier and can be understood as the “first battle of the Cold War ”. The justification for the blockade was initially based on the currency reform initiated by the Western Allies in the Trizone the days before . The Western Allies countered the blockade with the Berlin Airlift and with a counter-blockade.

prehistory

London Protocol on the Special Status of Berlin

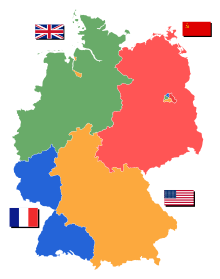

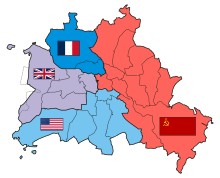

In the London Protocol on the zones of occupation in Germany and the administration of Greater Berlin , the four powers had stipulated in point 1: Germany will be divided into four zones for the purpose of occupation, one of which is assigned to one of the four powers, and a special Berlin area that is subject to the joint occupation sovereignty of the four powers. According to point 2 of the Protocol, this “special Berlin area” should “be occupied jointly by the armed forces of the USA , UK , USSR and the French Republic. For this purpose, the area of Greater Berlin is divided into four parts ”, later called“ Sectors ”. So after the unconditional surrender at the end of the Second World War, the city was geographically in the middle of the Soviet Zone as a four-sector city , but was supposed to be politically administered by the Allied Command , the four zones of occupation, on the other hand, by the Allied Control Council , which was also in the mutual Consensus made decisions on all material issues affecting Germany as a whole . In terms of international law , the Control Council exercised external power for “Germany within the borders as they existed on December 31, 1937”.

Guaranteed supply routes, excluded supply

When defining the sectors in the Yalta conference , no regulations had been made on the traffic routes between Berlin's western sectors and the western zones. On June 29, 1945, a few days before the entry of their troops into the western sectors, General Lucius D. Clay and General Weeks therefore asked their colleague Marshal Zhukov for four train lines, two roads and two air corridors to pass their soldiers and to be able to provide for their relatives. Zhukov initially only allowed one train line, one road (via Helmstedt-Marienborn) and one air corridor. In the Control Council, which had been set up in the meantime, the Soviets verbally assured the now three western city commanders on September 10, 1945 that up to ten trains per day would be allowed to travel through the Soviet Zone to West Berlin. This number was increased to sixteen trains per day on October 3, 1947 - but again not through a written contract. On November 30, 1945, the western city commanders were promised three air corridors between Hamburg , Hanover and Frankfurt am Main and Berlin in writing. On June 26, 1946, the Soviet side promised in writing that, under certain restrictions, the waterways through the Soviet Zone to and from West Berlin could also be used, through which the vast majority of the hard coal had previously come to Berlin from the Ruhr area.

In an informal meeting on July 7, 1945, before the establishment of the Berlin headquarters and the Allied Control Council for all-German issues, Marshal Zhukov stated that the western sectors of Berlin would not be supplied with food or coal from the Soviet Zone because the Soviet Zone was currently in the Soviet Union large quantities of food from the Soviet Union had to be supplied and the coal mining area in Silesia was now under Polish administration. Clay and Weeks accepted this. Although Zhukov's stipulations were initially circumvented in their own interest with the participation or approval of the Soviet side, but increasingly consistently implemented in the course of the blockade.

Increase in tension and disabilities

As early as April 1945, before the surrender and full occupation of Germany, Josef Stalin had explained to Milovan Djilas what he saw as a result of military occupations: “Anyone who occupies an area will also determine its social system. Everyone will introduce his system as far as his army can advance. ”Accordingly, socialist and communist regimes were established in the Eastern European states of Poland (1944), Albania (1944), Bulgaria (1944), Hungary (1945) from 1944 onwards. , Czechoslovakia (1948) and Romania (1948). The Western powers responded to this expansion with their containment policy from 1947 onwards , and the East-West conflict deepened. In Germany occupied by the Four Powers it was particularly evident. Deviating from the decision in the zone protocol, the Soviet Union increasingly took the view that the former Reich capital Berlin as a whole was part of its zone of occupation. It restricted the access routes from the western zones to the western sectors of Berlin again and again, mostly stating technical difficulties or formal requirements - according to the French President, a "war of pinpricks" developed (une petite guerre à coups d'épingles) : In mid-January 1948 , the Soviet Military Administration in Germany (SMAD) declared the transit permits for transports on the autobahn between Helmstedt and Berlin to be invalid. Ten days later the night train from Berlin to Bielefeld was stopped in the Soviet zone. 120 German passengers were sent back to Berlin, the rest, members of the British occupying forces, were only allowed to continue after waiting eleven hours. In February, an American-run train was obstructed, and further harassment by the Soviet occupation authorities also hit inland shipping.

On March 12, 1948, after a meeting with Stalin and military advisers , the Soviet Foreign Minister Molotov received a memorandum on how the Western Allies could be put under pressure by “regulating” access to Berlin. On March 26, 1948, the chairmen of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED), Wilhelm Pieck and Otto Grotewohl , visited Stalin. Pieck reported that the next election was in Berlin in October, he didn't think the SED would do better than it did in 1946, and he wished the Allies would be rid of. Stalin replied that perhaps the Allies could be "thrown out" of Berlin.

Since February 23, 1948, the London Six Power Conference took place with the exclusion of the Soviet Union . As early as an interim communiqué of March 6, 1948, close economic and political cooperation between the three western zones using the Marshall Plan (European reconstruction program) could be expected: “Since it has proved impossible to bring about economic unity in Germany and the eastern zone has been hindered is to play their role in the European reconstruction program, the three Western powers have agreed to bring about close cooperation between them and the occupation authorities in West Germany on all matters arising from the European reconstruction program in relation to West Germany. ”This contradicted the aim of the Soviet Union after the Eastern European satellite states were secured by a Soviet-dominated Germany as a whole . When the Supreme Head of the SMAD Marshal Sokolowski was refused information about previous conference results in the Control Council meeting on March 20, 1948, he read out a prepared text according to which the Soviet side would cease its participation in the Allied Control Council. From now on there were more disabilities. The restrictions on Western Allied troop transports on the access routes to Berlin from April 1, 1948 onwards were particularly serious. The British and Americans responded with the "small airlift " on April 3 , which had to supply their garrisons in Berlin for three days.

In February 1948, the United States and Great Britain proposed to the Soviet side in the Control Council a currency reform in Germany. The economic advantage for both sides resulted from the increasing devaluation of the Reichsmark. In the coming weeks, however, there remained a dispute in the committee appointed by the Control Council as to how and by whom the new currency should be controlled.

On June 16, 1948, after the Allied Control Council, the Soviet Union also left the Berlin Allied Command.

On Friday, June 18, 1948, the Western Allies announced that a currency reform would take place on June 20, 1948 in their zones of occupation, with the exception of the respective sectors in Berlin, and that the Deutsche Mark (DM, also Mark ”) to replace the Reichsmark (RM).

The extensive devaluation of the RM in the western zones suggested a massive outflow of RM from there into the Soviet Zone. For this reason, SMAD initially had all pedestrian, passenger train and car traffic between the western zones and Berlin blocked and freight traffic also strictly controlled on the waterways. In the first five days, around 90 million Reichsmarks are said to have seeped into the Soviet Zone. In addition, the German Economic Commission of the SBZ dated June 21, 1948, prepared a list of further protective measures, including a currency reform in the SBZ.

On June 22, 1948, a SMAD representative informed the representatives of the Western powers that they and the Berlin population were being “warned” that the Soviet side would apply sanctions in the economy and administration so that only the Soviet Zone currency would be used in Berlin.

The beginning of the blockade

The warning of June 22, 1948, the Soviet military administration followed up with the sanctions the very next day:

The large Zschornewitz power plant , which had supplied Berlin with electricity for decades, officially stopped supplying the western sectors on the night of June 24, 1948. Only a few areas were supplied with electricity from the Eastern sector via lines that did not follow the sector boundaries. The West Berlin power plants could not replace the missing electricity. Many lights in West Berlin went out. At around 6 a.m. on June 24th, freight and passenger traffic on the motorway from Helmstedt (British zone) to West Berlin was interrupted and the rails were blocked or interrupted . A few days later, contrary to the written agreement of 1946, the river and canal routes between West Berlin and the western occupation zones were blocked by patrol boats . In contrast, passenger and freight traffic to the eastern sector of the city and to the Soviet Zone were only more or less restricted and controlled, but not totally blocked. So the Berlin S-Bahn continued to the surrounding area.

When the imminent interruption was published, it was emphasized that supplying the western sectors from the Soviet occupation zone, including the eastern sector, would be "not possible". West Berlin, however, with its 2.2 million people at the time, was completely dependent on external supplies, like any city of this size. So far, 75% of them came from the west.

The Western powers had expected reactions to the currency reform, but they were largely unprepared for the Berlin blockade. To make matters worse, the relationship between Washington, London and Paris was strained, as it was not possible to agree on a common approach in Berlin. As a result, there was no coordinated Berlin policy of the Western Allies until the blockade. The US city commander Frank Howley went to the RIAS radio station as soon as the blockade became known and assured: “We will not leave Berlin. We will stay I don't know a solution for the current situation - not yet - but I know this much: The American people will not allow the German people to starve to death. "

Justification of the blockage

ADN , the official intelligence service of the Soviet occupation zone, asserted immediately after the blockade: "The transport department of the Soviet military administration was forced to stop all freight and passenger trains from and to Berlin tomorrow morning at six o'clock due to technical difficulties." A dozen bridges would have to be repaired along the motorway from Helmstedt to West Berlin. In contrast, however, was the "warning" of June 22, 1948 with reference to the currency reform. Sokolowsky named the even greater context when he told his Western colleague, British Military Governor Sir Brian Robertson on June 29, 1948 , that the blockade could be lifted if the results of the London Six Power Conference were "put up for discussion", and on July 3 1948 told Clay, Robertson and Kœnig that the "technical difficulties" would continue until the West abandoned its plans for a German government of the Trizone. On August 2, 1948, Stalin expressed this overarching connection to the ambassadors of the three Western powers in Moscow: The blockade could be lifted if it was assured that the implementation of the London resolutions would be postponed.

During the blockade

During the blockade, the Soviet Union intensified its efforts to increase the influence of communist forces in Berlin. Members of the city council assembly democratically elected in 1946 , the municipal council of Greater Berlin and the district council assemblies , district mayors and employees of the Berlin authorities who did not submit to the Soviet line were increasingly harassed, eventually threatened, defamed as incompetent or "saboteurs", summoned for interrogation , covered with house searches, arrested for a short time or removed from the SMAD and replaced by loyalty to the line. The daily work and meetings in the new town hall were increasingly hindered. As a result, more and more committees, along with their staff and files, moved their headquarters to the western sectors, especially the British sector. Police President Paul Markgraf , a member of the SED, who was appointed by the Soviet occupation forces , had the town hall searched several times, denied access to members of the municipal authorities and their staff, and had the town hall cordoned off. Although he was suspended at the end of July 1948, he remained in office and tolerated the paralysis of the city council by SED rioters. The Berlin city council met from September 6, 1948, with the exception of SED members in the British sector.

On September 9, 1948, 300,000 Berliners protested on the Platz der Republik against the incipient split in Berlin due to the blockade of the western sectors and the violent expulsion of the freely elected city councilors and magistrates from the eastern sector by the SED and the SMAD. The Berlin SPD leader Ernst Reuter gave his world-famous speech “You peoples of the world [...] look at this city!” When after the rally, people's police wanted to prevent participants in a protest march to the Allied Control Council from crossing the Soviet sector Pariser Platz a police officer took the 15-year-old student Wolfgang Scheunemann .

On November 30, 1948, an assembly of SED, FDGB, FDJ members and works councils convened by the SED in the Soviet sector declared the magistrate to be deposed and set up a provisional democratic magistrate with Friedrich Ebert junior as Lord Mayor. The Soviet occupying power immediately recognized this as the only legitimate Berlin magistrate. The political division of Berlin was thus completed.

The legislative period of the city council elected in October 1946 was to expire on October 20, 1948. The SMAD forbade preparations for a new election; the Western Allies approved them on October 7, 1948. Finally, the election in the western sectors took place on December 5, 1948, despite massive obstacles from SMAD and SED. The turnout was 86 percent, of which about 64 percent voted for the SPD and 19% for the CDU. The MPs elected Ernst Reuter Mayor on December 7, 1948 - as in June 1947, when his assumption of office was prevented by a Soviet veto and Louise Schroeder was in office until he was re-elected . The city council and the magistrate of the western sectors of Berlin had their seat from 1949 in the town hall Schöneberg .

During the blockade, around 110,000 people residing in West Berlin worked in the Soviet occupied area (in Berlin and the surrounding area) and around 106,000 East Berliners in the western part. In addition, the West Berlin population and companies could continue to shop in East Berlin and the Soviet Zone. There, too, there was only a limited supply and many goods were rationed. In order to restrict the flow of scarce goods to West Berlin, controls by East Berlin forces were increasingly carried out both in the U- and S-Bahn as well as in the streets in the border area between East and West Berlin. To improve controls, more than 50 of these roads were closed by April 1949. Goods brought in were often confiscated. After all, the transport of practically all goods from East Berlin to West Berlin had to be applied for and approved beforehand.

However, even before the blockade, the supply of food cards in East Berlin was more generous than in West Berlin. During the blockade, the districts of the Soviet occupation zone were forced through “solidarity campaigns” such as “The farmer shakes hands with Berlin” to send food to Berlin beyond the previous delivery target. The Soviet Union wanted to use the better supply in the east compared to the west of the city for propaganda purposes. For example, on July 21, 1948, with Order No. 80, SMAD offered to supply West Berliners with food and fuel from August onwards. For this purpose, every West Berliner would be assigned an East Berlin district in which he could register, expressly also for the purchase of fresh milk, which until then had hardly been delivered by the airlift. However, a maximum of 103,000 West Berliners made use of this offer. These and other actions, however, led to massive resentment among the population of the Soviet occupation zone, which was themselves much less well cared for than Berlin.

Looking for a solution

Even in the run-up to the blockade of Berlin, the governments of the Western powers were faced with the decision to give up the city. There are contradicting statements as to which of the leading Western military and politicians have spoken out for or against military measures in favor of West Berlin: One extreme of the views was embodied by the British Military Governor Robertson. Even before the blockade he had stated internally that Berlin could not be kept as an Allied-administered city in the middle of a Soviet-occupied zone. That corresponded to the opinion of the majority of West Germans at the time. On June 20, 1948, Robertson recommended in a secret letter to the political advisor to the British Foreign Office at the Control Commission, William Strang , to move away from Berlin as a four-sector city and instead aim for the capital of a "large part" of Germany. To solve the German question , free elections should be held throughout Germany, from which, in his estimation, the socialist forces should emerge as losers. This “Robertson Plan” was rejected by the British government as too risky and politically impracticable.

At the other end of the spectrum of opinion stood Winston Churchill , after all the opposition leader in the British House of Commons: On April 17, 1948, he proposed to the then Deputy Secretary of State Robert A. Lovett , referring to the US monopoly on nuclear weapons, to call on the Soviet Union to To evacuate Berlin and the Soviet Zone, otherwise “their cities would be wiped out”. This proposal was also rejected. General Clay, for example - according to many authors - expressed himself somewhat more moderately in favor of military intervention. He was of the opinion that a retreat of the Western Allies in Berlin would lead to a further advance of the Soviet Union, and was able to invoke the Truman Doctrine , which had the fight against communism as its goal. As early as April 13, 1948 in Frankfurt am Main he had declared: Nobody can drive us out of Berlin! On April 12, 1948, he is said to have suggested to US Army Chief Omar N. Bradley that if there was a renewed blockade, he should inform the Soviet Union that the Western Allied garrisons in Berlin needed reinforcements, and then demonstratively add an American, British and French division Set up Helmstedt and march into Berlin via the autobahn. Bradley, however, had refused, saying that he considered such a plan "currently not desirable" in view of longer-term goals in the western zones. According to another account, however, it was General LeMay who, in mid-April 1948, instead of the Small Airlift that was finally set up, pleaded for ground troops to be sent to Berlin and at the same time (nuclear-capable) B-29 bombers accompanied by fighter planes towards Soviet air bases in the Soviet Zone to let fly. Clay vetoed LeMay's proposal because of the risk of escalation. Two months later, after the Berlin blockade began, LeMay is said to have repeated his proposal. Clay is now said to have used him to campaign for a military solution: from Heidelberg, where he was for a meeting, he immediately flew back to Berlin and told his British and French colleagues there that he was sure that the Russians were only bluffing. Before his military superiors and the US President could forbid him to do so, he wanted, in agreement with LeMay, to move 6,000 men on the autobahn to West Berlin to break the blockade. Technicians could then repair the bridges - if something was really broken on them. Ambassador Murphy is said to have supported Clay in this. According to Clay's plan, if the Soviets attacked these ground forces, LeMay would destroy all Soviet airfields and aircraft in Germany by air strikes. On June 25, 1948, Clay told the press that only a war could drive the USA out of Berlin. On the same day, he reached a conference call to his superiors in the Department of the Army in Washington and said that the people of West Berlin would be in dire straits in two or three weeks. He was convinced that a supply convoy with troop support from the western zones could reach Berlin and that such a show of force would prevent rather than promote the development of war. In a manner typical for him, Clay had already called the commander of the US Air Forces in Europe on June 24, 1948, Curtis E. LeMay and asked for food to be flown into West Berlin. US President Harry S. Truman ultimately rejected military action because of the risk of a war provocation. Therefore, on June 26, 1948, Clay was forbidden from doing anything that posed the risk of war. However, on June 28, 1948, Truman ordered three groups of the US Air Force's long-range B-29 bombers capable of nuclear weapons to be transferred to Europe. One of them was briefly stationed at the Fürstenfeldbruck airfield in Bavaria before it was relocated to the other two in England. The machines were not equipped with atomic bombs, however.

Other authors, on the other hand, assert that it was Clay (as in April 1948) and LeMay who advised against military threats: LeMay, for example, advised President Truman to use an airlift because it was "unnecessary" to relieve Berlin Deploy ground troops.

It is unanimously reported that Clay's British colleague Robertson has always been strictly against the use of military force to break the blockade. That would mean war. The British side would not support this, and neither would the French. When Clay finally prohibited actions of a military nature, Robertson suggested that the airlift , which had been carried out at a low level since the Small Airlift in early April 1948, for the British and US garrisons (Operation Knicker) should be expanded to include an airlift that also served the civilian population could supply all three western sectors. Clay picked up the thought immediately.

Berlin Airlift

After the “Small Airlift” at the beginning of April 1948, the head of the British Air Force Associations in Berlin, Reginald “Rex” Waite , had worked out how the western sectors of Berlin could be supplied for a few weeks in Operation Knicker via an airlift. With reference to this, General Clay ordered an airlift to be established on June 25, 1948 . On June 26th, the first US Air Force aircraft flew to Tempelhof Airport in Berlin and started Operation Vittles (Operation Provisions). The British Air Force participated in the operation with Operation Carter Patterson, soon renamed Operation Plainfare.

The politicians in Berlin were also aware of the unfavorable military situation and the difficulty of air supply. The elected mayor of Berlin, Reuter, said on June 25, 1948, after recalling Willy Brandt , that although he admired Clay's determination, he did not believe that the supply would be possible in this way. Even Otto Suhr , at that time, after all, head of the Berlin City Council , said that the Western Allies would eventually give up and leave Berlin. Accordingly, when asked by the Western Allies in July 1948, 86% of Berliners said that despite the airlift, Berlin would not get through the winter, but would have to capitulate to the Russians in a few months. The East Berlin media predicted that anyway. In the western zones, too, the support of enclosed West Berlin through taxes such as the Berlin emergency sacrifice met with skepticism and criticism. With the continuation of the airlift, however, confidence increased among the West Berliners. A poll in October 1948 by the US military government showed that nine out of ten Berliners now stated strictly that they would prefer the conditions of the blockade to communist rule. 85% of respondents were now confident that the airlift would get them through the winter.

"General Winter" fails

The prospect of supplying the western sectors with an airlift was initially assessed as poor by the western allies. Rather, the airlift should primarily help to gain time for negotiations. It was clear from the start that the winter months would be particularly difficult: the hunger winter of 1946/47 two years earlier was extremely hard and long in Berlin too. Together with the malnutrition of large parts of the population and the destruction of many homes, it had led to several thousand deaths from the cold. The western allies estimated that even with average weather conditions, due to poor visibility, impaired runways and icing of the waiting aircraft, about 30% less tonnage could be flown in in winter than in summer. At the same time, however, the need for coal for heating would increase significantly. Under these circumstances, all stocks would be exhausted by the third or fourth week of January. The British commander, Robertson, told his foreign policy advisor, Strang, at the turn of 1948/49 that “everything would depend on the weather”. As recently as February 1949, he insisted that the Airlift would not be able to supply West Berlin “permanently”. The Soviet side expected that “General Winter” would come to their aid this time, as it did during the Second World War. In favor of West Berlin, however, “General Winter” failed during the blockade: the winter of 1947/48 had already been less severe. The winter during the blockade was downright mild: the average temperatures were more reminiscent of late autumn or the beginning of spring. Whereas in the winter of 1946/47 there were 65 days on which the thermometer in the Dahlem weather station remained below 0 degrees Celsius, in 1947/48 it was only 14 days and during the winter blockade it was only 11 days. The result was that the airlift could just fly in the western sectors' need for coal and food even in winter. With a daily ration of 400 grams of bread, 50 grams of food, 40 grams of meat, 30 grams of fat, 40 grams of sugar, 400 grams of dried potatoes and 5 grams of cheese for the "normal consumer", West Berliners did not starve to death, even if they were constantly hungry . With an allocation of 12.5 kilograms of wood, coal or coal substitute per capita for the entire winter, well-heated apartments were out of the question, but the public warming rooms were an addition. Electricity and gas were mostly switched off during the day, so they cooked at night. The cooking boxes , which had already been propagated in World War I , were once again widely used here to cook the food and let it finish cooking by noon.

Supply just secured

Through better organization, more and better trained personnel, and more and larger aircraft, the Western Allies were able to achieve steadily increasing cargo performance. Electricity, coal for heating and food still had to be rationed, but the supply gradually improved and was ultimately better for some goods than before the blockade. To a modest extent, goods produced in the western sectors could even be exported back to the western zones as air freight.

Deadly aggravation

When the airlift was not abandoned, but steadily increased its performance, the Soviet side increasingly obstructed the air corridors. This happened, for example, through maneuvers on the ground with shooting grenades into the corridors, but above all through the penetration of Soviet aircraft into the corridors, which then deliberately approached the clumsy cargo planes and maneuvers around them.

On October 14, 1948, Clay went to see his Soviet colleague Sokolowski. He denied any wrongdoing on the part of the Soviets; rather, a C-54 flew provocatively outside the corridor. Such recently repeated violations on the part of American aviators would now have invalidated the 1945 agreement on the Western Allied air corridors. Clay then asked LeMay for fighter planes to protect the air corridor. On October 18, 1948, in the air corridor over Berlin, after the fire was opened by a Soviet aircraft, a Soviet yak was reportedly shot down and several yaks were damaged by US warplanes.

Counter-blockade

Since September 1948, the Western powers prohibited the delivery of certain goods to the Soviet Zone and made the export of other goods dependent on licenses: to an increasing extent, goods that were absolutely prohibited from export were included in an A list, and goods requiring authorization in a B list. In April 1949, Heinrich Rau , chairman of the East German Economic Commission , complained of a state of economic stagnation in the Soviet Zone, which was due to the performance of West Germany. On May 6, 1949, Tjulpanow ordered the SMAD to take advantage of the anticipated lifting of the counter-blockade to replenish supplies. At the same time, however, officials from the Economic Commission were informed that the Berlin blockade would be resumed and that the shortage of the East German economy would have been eliminated if the western sectors had not "fallen" by autumn. The effect of this Western embargo was reinforced by the fact that the economy of the Soviet Zone initially remained in a poor state even after the currency reform of 1948: By the end of 1947, probably 65% of industrial capacity had been transported to the Soviet Union as reparations . In addition, high taxes still had to be paid to the Soviet Union from ongoing production. In addition, there were conversion problems due to the land reform and the politically desired weakening of the private economy in favor of Soviet joint-stock companies and state- owned companies . Economic impulses like the Marshall Plan in the western zone were lacking in the Soviet Zone. Since the beginning of 1949 tens of thousands fled from there to the West every month , many of them of working age and well educated. In mid-1949 398,000 East Germans were registered as unemployed.

End of the blockade

The airlift was obviously able to guarantee supplies to West Berlin for a long time, at least in summer and during mild winter weather. Politically, it also demonstrated the will of the Western powers to protect West Berlin from Soviet annexation . The West Berlin population felt that the blockade was part of the Soviet threat. On the other hand, the relationship between the three western allies and with the West Berlin population had improved significantly as a result of the events. There were also the negative consequences of the counter-blockade on the economy of the Soviet Zone and East Berlin. The Soviet Union had therefore been secretly negotiating with the Western powers to end the blockade since February 1949. On the basis of the Jessup-Malik Agreement , General Chuikov finally had the blockade lifted by Order No. 56: Shortly before midnight from May 11 to 12, 1949, the western sectors were supplied with electricity again and at 12:01 a.m. the blockade was terminated the land and water transport routes are abolished. With several renewed restrictions and corresponding protests by the western city commanders, by autumn 1949 the traffic routes were again as they had been granted by the Soviet side before the start of the blockade. Airlift flights were gradually reduced until stocks lasted for about 2 months, then officially ceased on September 30, 1949.

During the Airlift, US Commander Clay had already asked for his transfer several times in disputes with his superior departments, and on May 15, 1949, he actually submitted his resignation as military governor. At the farewell ceremony, Mayor Reuter paid tribute to Clay's work for the city; The President of the Parliamentary Council Konrad Adenauer , soon afterwards the first West German Federal Chancellor , had also come.

Consequences of the blockage

Overarching political context

Egon Bahr , himself affected by the blockade and later co-developer and advisor to Willy Brandt in the policy of détente , judged:

“Lenin is said to have said that whoever has Berlin has Germany, and Germany is the key to Europe. The blockade of Berlin by the Soviet Union, which began in June 1948, is the first battle of the Cold War - and ended with Stalin's defeat: The use of his starvation weapon failed, and around two million inhabitants of the city's western sectors were airlifted by the Americans for 15 months supplies essential goods. "

By the Soviet blockade of the already solidified in the Weimar Republic -scale anti-Communist consensus in the West. Special campaigns such as at Christmas 1948 and Easter 1949 and gestures such as Operation Little Vittles , initiated by the pilot Gail Halvorsen , as well as intensive public relations work and knowledge of the fatal accidents on the Western Allied side as part of the airlift gradually brought confidence and increasing recognition of Western Allied aid. In the western zones and for the West Berliners "'islanders' and world citizens at the same time", the Berlin blockade and the airlift led to a transition in perception: the occupiers became popular protective powers against the Soviet Union, which was now finally perceived as a threat, even " The contact between the political class and the British, French and Americans was warm ”. The blockade and the airlift became the turning point in relations between the defeated Germans and the Western Allies and, together with the Marshall Plan, contributed to improving German-American relations in particular.

As a sign of the looming Cold War, a transatlantic defense alliance, NATO , was concluded in Washington on April 4, 1949 . The establishment of a western state, the Federal Republic of Germany , which at first could only act on behalf of western Germany, although it was responsible for the whole of Germany in its own understanding, was influenced by the Berlin blockade. The Basic Law was promulgated on May 23, 1949, but according to the Allies it should not (initially) apply to Berlin.

Berlin was the scene of a serious conflict two more times: in 1958, Khrushchev issued his Berlin ultimatum , in which he called for the city to be converted into a so-called Free City , and in 1961 the Berlin Wall was erected.

Follow on site

As a result of the blockade, the stockpiling of food, raw materials and other essential goods for the population , later referred to as the Senate Reserve , was ordered in West Berlin .

1951 commemorating the airlift and their victims the Airlift Memorial (also called "hunger rake" or "hunger claw") is hereby established in Berlin. Since 1985 and 1988, respectively, there have been copies at Frankfurt Airport and at the Celle Army Airfield . The three struts at the end of the figure refer to the air corridors used at the time.

In 1959, Willy Brandt set up the non-profit foundation "Airlift Thanks". After his appeal for donations, around 1.6 million DM came together. Relatives of the victims of the Airlift could be financially supported from the interest of the foundation capital. Today the foundation supports projects and ideas that deal with the topic of “Airlift and Berlin Blockade”.

See also

- History of Berlin

- History of Germany

- Berlin question

- Berlin crisis

- History of the Berlin S-Bahn

- Allied Museum

literature

- Matthias Bath: The Berlin blockade 1948/49. Stalin's reach for the German capital and Berlin's struggle for freedom. Neuhaus Verlag, Berlin 2018, ISBN 978-3-937294-11-7 .

- Lowell Bennett: Bastion Berlin. The epic of a freedom struggle. Friedrich Rudl. Publishers Union, Frankfurt am Main 1951.

- Corine Defrance , Bettina Greiner , Ulrich Pfeil (eds.): The Berlin Airlift. Cold War memorial site. Christoph Links, Berlin 2018, ISBN 978-3-86153-991-9 .

- Udo Wetzlaugk: Berlin blockade and airlift 1948/49. Landeszentrale f. Polit. Education, Berlin 1998.

- Daniel A. Harrington: Berlin on the Brink. The Blockade, the Airlift and the Early Cold War. University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky, USA 2012, ISBN 978-0-8131-3613-4 .

Web links

- The Berlin blockade. ( Memento of February 8, 2008 in the Internet Archive ).

- Berlin blockade and airlift at Lemo

- Airlift project (400 documents on the Berlin blockade and airlift; original newspaper articles, banknotes, political documents, photos, everyday life) - offer by verkehrswerkstatt.de for schools

- Literature list (PDF) stiftung-luftbrueckendank.de

- The Berlin Crisis 1948/1949. In: United States Department of State (Ed.): Foreign Relations of the United States (FRUS) series, Chap. IV, pp. 867-1284.

Individual evidence

- ↑ United States Department of State (Ed.): The Berlin Crisis 1948/1949 in: Foreign Relations of the United States (FRUS) series, chap. IV, pp. 867-1284.

- ↑ Dirk Rotenberg, Otto Büsch: Berlin Democracy Between Securing Existence and Change of Power: The Transformation of the Berlin Problem 1971 to 1981 . In: Writings of the Historical Commission in Berlin, Volume 5. Haude & Spener, 1995, ISBN 978-3-7759-0371-4 , p. 547 ff.

- ^ Rudolf Luster: A Berliner for Europe. Libertas, 1989, ISBN 978-3-921929-84-1 .

- ↑ Reiner Kunze: Robert Havemann 70. P. 54 in: Edition 48 of Europäische Ideen, Verlag Europäische Ideen, 1980, ISSN 0344-2888 .

- ↑ a b Egon Bahr: Eastward and don't forget anything! Politics between war and understanding. Herder, 1st edition 2015, ISBN 978-3-451-06766-2 .

- ^ The Berlin Airlift, 1948–1949. In: US Department of State (Ed.): Milestones: 1945–1952. Retrieved October 23, 2016.

- ^ Protocol on the zones of occupation in Germany and the administration of Greater Berlin, London, September 12, 1944 in the German translation of the version when it came into force on 7/8. May 1945.

- ↑ See Michael Schweitzer : Staatsrecht III. Constitutional law, international law, European law. 10th edition 2010, para. 615 ; Daniel-Erasmus Khan : The German state borders. Legal history basics and open legal questions. Mohr Siebeck, 2004, p. 89 fn. 174 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Ann Tusa, John Tusa: The Berlin Blockade. Coronet Books, Coronet Ed. 1989, ISBN 0-340-50068-9 .

- ↑ a b c The other side of the blockage. Der Tagesspiegel from June 22, 2008.

- ^ Geoffrey Roberts: Stalin's Wars: From World War to Cold War, 1939-1953. Yale University Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0-300-11204-7 , p. 405.

- ↑ John Lamberton Harper: American Visions of Europe: Franklin D. Roosevelt, George F. Kennan, and Dean G. Acheson. Cambridge University Press, 1996, ISBN 978-0-521-56628-5 , p. 122.

- ↑ a b Wolfgang Benz: Berlin - on the way to a divided city. In: Federal Center for Political Education (Ed.): Information on political education. Issue 259, 2005.

- ↑ Laufer, Kynin (ed.): The USSR and the German question, 1941–1948. Volume 3, p. 589, cit. n. Manfred Wilke: The Path to the Berlin Wall: Critical Stages in the History of Divided Germany. Berghahn Books, 2014, ISBN 978-1-78238-289-8 .

- ↑ a b c d Roger Gene Miller: To Save a City: The Berlin Airlift 1948-1949. Air Force History and Museum Program, United States Government Printing Office , 1998, 1998-433-155 / 92107; afhso.af.mil (PDF; 9.8 MB) p. 11.

- ^ The communiqué of the London discussions on Germany of March 6, 1948.

- ↑ a b Wolfgang Malanowski: 1945–1948: Schlamassel Berlin - Currency Reform and Soviet Blockade 1948/49. In: Der Spiegel special , issue 4/1995, pp. 132-138

- ^ "We are warning both you and the population of Berlin that we shall apply economic and administrative sanctions that will lead to the circulation in Berlin exclusively of the currency of the Soviet occupation zone."

- ^ A b c Daniel F. Harrington: Berlin on the Brink: The Blockade, the Airlift, and the Early Cold War. University Press of Kentucky, 2012, ISBN 978-0-8131-3613-4 .

- ↑ a b c d Richard Reeves: Daring Young Men: The Heroism and Triumph of The Berlin Airlift, June 1948 - May 1949. Simon and Schuster, New York 2010, ISBN 978-1-4391-9984-8 .

- ^ Excerpts from the RIAS report by Jürgen Graf and Peter Schultze from the New Town House on September 6, 1948 (disruption of the StVV meeting). ( Memento from February 20, 2013 in the Internet Archive ).

- ^ German stories. Berlin blockade. (No longer available online.) In: deutschegeschichten.de. Cine Plus Leipzig / Federal Agency for Civic Education (bpb), archived from the original on November 17, 2015 ; Retrieved April 24, 2015 .

- ↑ Jeremy Noakes, Peter Wende, Jonathan Wright (Eds.): Britain and Germany in Europe, 1949–1990. Studies of the German Historical Institute London. Oxford University Press, 2002, ISBN 978-0-19-924841-4 .

- ^ "To tell the Soviets that if they do not retire from Berlin and abandon Eastern Germany [...] we will raze their cities"

- ↑ a b c d Avi Shlaim: The United States and the Berlin Blockade, 1948–1949: A Study in Crisis Decision-making . In: International crisis behavior series , Vol. 2, University of California Press, 1983, 463 pp., ISBN 978-0-520-04385-5 .

- ^ Benjamin Schwartz: Right of Boom: The Aftermath of Nuclear Terrorism. The Overlook Press, New York 2015, ISBN 978-1-4683-1154-9 .

- ↑ Ken Young: US 'Atomic Capability' and the British Forward Bases in the Early Cold War. In: Journal of Contemporary History. 42-1, 2007, ISSN 0022-0094 , pp. 117-136.

- ^ A b Peter G. Tsouras (Ed.): Cold War Hot: Alternate Decisions of the Cold War. Tantor eBooks, 2011, ISBN 978-1-61803-023-8 .

- ^ Ralph H. Nutter: With the Possum and the Eagle: The Memoir of a Navigator's War Over Germany and Japan. In: North Texas Military Biography and Memoir Series. No. 2, 2005, University of North Texas Press, ISBN 978-1-57441-198-0 .

- ^ Judith Michel: Willy Brandts America picture and policy 1933–1992. Volume 6, page 91 in: Dittmar Dahlmann, Christian Hacke, Klaus Hildebrand, Christian Hillgruber, Joachim Scholtyseck (eds.): International Relations. Theory and history . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2010, ISBN 978-3-86234-126-9 .

- ^ Helena P. Schrader: The Blockade Breakers: The Berlin Airlift. The History Press, UK 2011, ISBN 978-0-7524-6803-7 .

- ^ A b Paul Schlaak: Wetter und Witterung in Berlin from 1945-1948 . In: Berlin monthly magazine ( Luisenstädtischer Bildungsverein ) . Issue 12, 2000, ISSN 0944-5560 ( luise-berlin.de ).

- ↑ Stefan Paul Werum: Union decline in socialist construction: the Free German Trade Union Confederation (FDGB) 1945 to 1953. In: Writings of the Hannah Arendt Institute for Totalitarian Research, Hannah Arendt Institute for Totalitarian Research , Volume 26. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2005 , ISBN 978-3-525-36902-9 .

- ↑ Allied Occupation of Germany, 1945-52 . In: Archive for the US Department of State.

- ↑ In the interest of the starving population - the foundation of the district assembly in the First World War . ( Memento of October 21, 2007 in the Internet Archive ; PDF; 4.2 MB) p. 6

- ↑ Esslingen local history ( Memento from July 2, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) (p. 94; PDF; 545 kB)

- ↑ Kochkiste during the Berlin blockade

- ↑ According to information not otherwise confirmed, on October 13, 1948, an American C-54 was rammed by a Soviet fighter aircraft from the manufacturer Jakowlew (Jak) in the air corridor near Tempelhof and crashed (with the loss of the crews).

- ↑ Dierk Hoffmann: Structure and Crisis of the Planned Economy : The Labor Management in the Soviet Zone / GDR 1945 to 1963 (= publications on Soviet Zone / GDR research in the Institute for Contemporary History, Vol. 60), Oldenbourg, Munich 2002, ISBN 978-3- 486-59619-9 , p. 108.

- ↑ a b quotation from Jürgen Dittberner : Grand coalition, small steps. Political culture in Germany. Logos, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-8325-1166-0 , p. 92.

- ↑ Foundation Airlift Thanks. (PDF; 2.7 MB) stiftung-luftbrueckendank.de