Bradu (Sibiu)

|

Bradu Girelsau Fenyőfalva |

||||

|

||||

| Basic data | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| State : |

|

|||

| Historical region : | Transylvania | |||

| Circle : | Sibiu | |||

| Municipality : | Avrig | |||

| Coordinates : | 45 ° 43 ' N , 24 ° 19' E | |||

| Time zone : | EET ( UTC +2) | |||

| Height : | 420 m | |||

| Residents : | 1,045 (2002) | |||

| Postal code : | 555201 | |||

| Telephone code : | (+40) 02 69 | |||

| License plate : | SB | |||

| Structure and administration | ||||

| Community type : | Village | |||

Bradu (outdated Brad ; German Girelsau or Gierelsau , Hungarian Fenyőfalva ) is a village in the Sibiu district in the Transylvania region in Romania . It is part of the small town of Avrig (Freck) .

location

The village is located on the Olt (Alt) river about twenty kilometers from the district capital Sibiu (Hermannstadt) , on the national road 1 (part of the European route 68 ) in the direction of Făgăraș (Fogarasch) or Brașov (Kronstadt) .

history

Traces of a Roman settlement have been discovered in the north-west of the village .

So far, there are no archaeological finds that would prove a major settlement before the 13th century in the area of today's village. However, there are individual references to Roman settlements in the neighborhood, such as those on the route between Bradu and Săcădate (Sakadat) . The accumulation of graves in the north in the direction of Cașolț (box wood ) , which was often associated with Bradu in the past, brings modern researchers into connection with Noro-Pannonian settlers and Illyrians .

The grave goods and artefacts found do not allow any direct reference to a Dacian-Roman culture, which could then provide evidence of settlement continuity ( Dako-Roman continuity theory ) in the area until the arrival of the German settlers ( Hospites Theutonici ) .

The village and its names

In the existing documents from the 14th century, the place is named in Hungarian as "feneufolva", "fenyefalva" and in Latin as "insula Gerhardi" in accordance with the linguistic and historical circumstances in Transylvania.

The Romanian village name "Brád" (later "Bradu") has only been documented in the sources since the middle of the 18th century. "Brád" (fir) is the translation from the Hungarian "Fenöfalva" (fir village), as the village is already called in Latin sources in the 14th century.

The place is documented in the church sources and those of the Sibiu district assembly from the 14th century as "insula gerhardi" and is even in documents together with "Fenöfalva". Both names stand next to each other and should also mean a place, but this does not rule out that the German settlers (Hospites Theutonici) founded a new place next to an older place called "feuneufalva". It is also possible that the old place was a former Szekler settlement and that the name "Fenöfalva" as a "pine village" comes from them. However, these are only assumptions that have not been proven by sources.

The Latin name "insula gerhardi" is similar to "insula christiani" ( Cristian / Großau ) a Latin place name. To whom the name “gerhard” goes back in the Latin sources, it cannot be clarified what has led to various speculations. Whether it is the former founder of the place ( Lokator , Wikipedia) with the name "Gerhard" or whether this name comes from the presumed patron of the local church "St. Gerhard ”is open. The latter assumption is based on a note from the report by Michael Lebrecht, pastor in Șura Mică (Kleinschubbing) .

"Girelsau or Gerharsds-Au, lat. Fanum Sti. Gerhardi, vulgo Giresä, a beautifully built village in a pleasant area near the old river ... "

This could mean St. Gerhard von Csanád , who participated in the Christianization of the Hungarians in Transylvania and is one of Hungary's patrons. It is also possible that it is St. Gerhard of Clairvaux , who was venerated by the Cistercian order . This order was very active in Transylvania, founded the Kerzer Abbey ( Cârța ) and probably had a small abbey in the neighboring municipality of Săcădate.

On the other hand, the name " Gerhard " was a popular count name from the 11th to the 13th century and is widely documented among the Luxembourgers , on the Rhine and Moselle and in Flanders . It is therefore possible that the name "insula gerhardi" goes back to a secular count who was probably venerated by the German settlers as a leader and founder and who gave the place his name. This is supported by the variant "insula gerhardi", because a designation "insula Sancti Gerhardi" would refer to a saint named Gerhard, a designation that would have been common at that time.

What is certain is that the German name “Girelsau” comes from the Latin name “insula gerhardi” and the sound “Gerhardsau” is already used from 1468, when the place belongs to the communities (“Pertinenzen”) that are dependent on Sibiu. Names such as “Gerardsau”, “Gerysau”, “Geresaw” also appear during this period.

The original mention of the place can be found in connection with people. A pastor Mathias (plebanus Mathias de Feneufolua) is mentioned in an undated source. The content shows that it was written between 1311 and 1319. The document comes from the royal chancellery and is addressed to the ecclesiastical office of the Archdiocese of Alba Iulia with the request of the Hungarian King Charles I Robert (1288–1342) to give this pastor a canonical and a benefice. Since Mathias is referred to by the king as "fidei et familiari capellano nostro (our loyal and belonging to the royal court)", he must have already been in the service of the royal family. It can therefore be assumed that the name "de Feneufolua" denotes the place of origin Mathias. Perhaps he belonged to the count's family, which is then mentioned in the following documents in the 14th century.

The dynasty of the Counts of Girelsau carries the designation "de insula Gerhardi" as well as "de Fenyefalwa", "de Foniefolwa". "De Fenyefalwa".

Hennyngh de Fenyefalwa is married to a daughter of Count Nicholas of Tolmach ( Tălmaciu ). Since he is only mentioned later (1337) in connection with his son and his son is already called "comes" (Count), his work as a count around 1300 should be certain. The son Christian is mentioned in 1335 as "comes Christian de insula Gerhardi".

Two sons of this are named in documents: Nikolaus and Petrus (mention: 1373 as "Nikolaus ... Petrus, filii Cristiani de Foniefolwa", Petrus 1387 as "Petrus de insula Gerhardi"). Count Petrus settles the border dispute between Avrig (Freck; villa Affrica ) and Săcădate (villa Czectat) for the Sibiu Chair , which shows him to be the confidante of the Sibiu Chair .

Peter has a daughter Katharina (mentioned in 1413 as "Katharina filia Petri de Ffenyfolwa") who is married to a James (mentioned: 1413 as Jakobus "filius Samsonis de dicta Fenyefalwa"), who is probably identical with James, who is in one later document from 1431 as "Comes Jakobus de insula Gerhardi" is mentioned. Jakobus is documented as the last Count of Girelsau. The Counts of Girelsau have a continuous count dynasty from around 1300 to Jakobus. Through the marriage of Katharina of this family to James, the son of "Sampson de Fenyefolwa", the dynasty changes and James becomes Count.

Thereafter, no more counts are mentioned in a document and at the end of the 15th century the municipality is administratively bound to Sibiu and is therefore no longer an independent municipality.

Whether the well-known field name "aff der Burch" refers to a former castle of this count family cannot be confirmed on the basis of sources, but it is probable.

In individual documents names like that of Ortshann ( Schultheis ) Jacobus Atzmann (mentioned 1468) and a Paulus Atzmann (1494) can be found. In the 16th century, the Ortshann Laurentius and residents such as Jakobus Tomas, Andreas Kapus, Nikolaus Frank, Clos Axmann, Gaspar and Andreas Sacharias and Johannes Kewn ( schoolmaster in Heltau ) appear in various accounts of the city of Sibiu . Family names such as Schneider, Teiller, Wenrich, Schieb, Gonnterth, Borner, Talmescher, Hein, Seydner, Schunn and Rapolt are also mentioned.

In these documents there are no Wallachians as a social group . However, it cannot be ruled out that individual Romanian families were already serving as servants in the village at this time , but there is no evidence for a larger settlement in the village.

From the 16th century the Sibiu magistrate exercised the usual jurisdiction. Its representative in the place was the Ortshann (Schultheiß), who was elected from the Saxon population.

Immigration of the Wallachians (Romanians) and Roma

Due to the chaos of war and epidemics, there was a shortage of workers in agriculture in the 17th century, which also affected Girelsau. Now Wallachians and Roma settle on the outskirts of the Saxon villages of the Königsboden , which was supported by the settlement policy of the Habsburgs from 1688.

However, this did not go without tangible conflicts, since the new settlers had to be granted not only residential areas, but also arable and pasture areas and access to deforestation.

Girelsau is one of the villages in which the Wallachian immigrants were fought in 1775, as the protocols of the Sibiu municipal authorities show. 35 Romanian families were evacuated by order of the Sibiu municipal authorities. In 1776 the Viennese government ordered the Romanians to be resettled. The minutes speak of a "Vonya Urss" whose house in Girelsau was destroyed. At the urging of the responsible authorities, he is compensated and the house is being rebuilt. Other incidents from Girelsau have not been reported. It is possible that "Vonya Urss" is the ancestor of the Ursu family , which has been documented for centuries and who built up and shaped the Romanian school system in Girelsau.

An insight into the immigration of the Wallachians to Girelsau is given by the statistics from 1733, which were compiled on behalf of the bishop of the Church united with Rome, Inocențiu Micu-Klein . In these statistics Girelsau is not mentioned at all as a place with Romanian residents. Only in the following statistics from 1750 does “Brád” appear with 117 “souls” (Animae Universim). It is the first documented mention of the place with "Brád" (with Hungarian pronunciation). So this year there were 117 Romanian residents in Girelsau. However, the place is ecclesiastically counted as a branch (hic Pagus est filial. Szekedate) to Săcădate, without an existing church and pastor. The neighboring places, which appear in the statistics from 1733, already have parishes with churches and pastors (e.g. Freck 1,048 souls with a church and pastor, Săcădate 893 souls and five pastors). Between 1733 and 1750 there was a clear movement of immigrants to Girelsau, who are still called "Wallachians" in the sources.

In official statistics from 1761/62, the population in Girelsau was made up as follows: 65 Saxon , 12 Wallachian and 10 Roma families. From the 18th century onwards, the Girelsau population included the Saxons and Romanians as well as Roma.

In 1818 the Evangelical Lutheran pastor, W. Woner in Girelsau, recorded 112 Saxon, 65 Wallachian and 21 Roma families in his statistics.

In the following decades the Romanians develop into a closed social ethnic group in the village. The Romanians had to fight for their status as a recognized and equal national community alongside the Hungarians and Saxons since the end of the 18th century.

The Roma remained excluded from these rights and lived in the village as day laborers and self-employed craftsmen. They settled on the outskirts of the village and were not involved in political decisions.

Both Romanian and Saxon men from the village were involved in the warlike revolutionary years of 1848/1849 . The flag (damaged) of a Saxon participant is preserved in the archive of the parish. It bears the inscription: "Michael Schunn 1848 in Waschahei (?)" And on the reverse the text from Psalm 46: 9-11 ( Psalms ): "Come here and see the works of the Lord [who causes such destruction on earth] who puts an end to wars [in the whole world], who breaks bows, smashes spears and burns chariots with fire, be still and realize that I am God. "

At the beginning of the 20th century, the proportion of the Romanian population in the village was greater than that of the Saxons: 594 Romanians and 487 Saxons were counted, whereby the Roma did not appear in these statistics, for whatever reason.

After 1918, Transylvania was gradually incorporated into the Kingdom of Romania . This changed the political situation, which also affected Girelsau. The Saxon population now had to act from the position of a minority and, in turn, fight for their rights and the preservation of their traditions. The administrative function of the Saxon Hannen und Richter was abolished. The last Saxon Hann ( Schultheis ) is Johann Krauss (May 26, 1870 to May 20, 1923).

The first Romanian mayors counted from 1920: GC Urs, S. Balteșiu, I. Bădilă, V. Mircea and I. Dan. The Saxon representatives are: S. Schieb (Deputy Mayor) and J. Schunn (Herold / local servant). The Saxons remained the dominant economic force in the place.

Between the otherwise strictly separated ethnic groups of the Romanians and Saxons, the situation in Girelsau also came to a head in the course of the ethnic politics in Romania in the 1930s and 1940s. The ethnic groups were now agitated against each other in the course of racial ideology. Ethnicity now became a “racial identity”, with the Roma being seen by both sides as “inferior people” according to political guidelines. Influenced by the racial ideology of the German National Socialists, the rejection of the Romanians by the Saxons also increased in Girelsau from 1935 onwards. The infiltration of the school system by the “ movement for the renewal of the Germans ” also took place in Girelsau. Here, too, the National Socialist-minded organizations emerged. The defamation of the Romanians as an "underdeveloped race" led to deep emotional rifts between the two ethnic groups. What happened to the Roma from Girelsau during this time has not yet been scientifically recorded.

The sad tragedy of the Saxon residents in Bradu after 1944

After 1944, the painful tragedy of the German villagers followed, known as the deportation of Romanian Germans to the Soviet Union .

An affected woman from Girelsau reports: “Then came January 13th 1945, a day that none of us Saxons will ever forget. A terrible, freezing winter day, the day on which all women, men, boys and girls, aged 17 to 50, were deported to Russia. ... Russians and Romanians went from house to house together, tore the young children from their mothers' breasts and drummed up everything that could be used as labor in Russia. We will never forget the smiling faces of the Romanians and Gypsies who accompanied us on the way to the collection point. The bells rang goodbye from our church tower. For many it should be a goodbye forever.

Only old people and children remained in the village. For 17 days we sat crammed together in a truck in the freezing cold of January, huddled tightly together on makeshift beds so that we could protect each other from the cold. On the 18th day we arrived in the Russian Donets Basin , where we were driven into the camp on foot through the freezing snowstorm. ... After 5 years the last ones came home and found poor old people in our village, from whom everything, everything had been taken: cattle, farmland, yes even partly driven from their houses. The gypsies all became communists and were given our land and livestock and agricultural implements. "

86 people were abducted from the village for forced labor, 53 of them women. 56 returned to the village, 13 died and were missing and 17 came to Germany from captivity. The agrarian reform of 1945 robbed the Saxons of their livelihood. The arbitrary expropriation of the Saxon farmers by the Romanian authorities until the old people and children left behind were thrown out of their houses and they had to live in the stables with the cattle. The members of the organization “Frontul Plugarilor” ( Front of the Plowers ) and their armed vigilante groups were particularly active . Some Romanian farmers who immigrated to the village and appropriated cattle and agricultural implements of the Saxons benefited from this Stalinist “punishment and re-education measure” of the Germans. A few poor Romanians now played an extremely negative role. They let themselves be carried away by the Stalinist propaganda against the Germans and presented themselves as "new masters". This situation also deterred the Saxons living abroad after the war from returning to their homeland.

Every Saxon family in the village was affected by the catastrophic consequences of the post-war period. Even those who did not allow themselves to be blinded by the ideology of the National Socialists. But there were “true friends” on the part of the Romanian population who protected the old and children of the Saxons who had not been deported to the Soviet Union from brutal punitive actions by some (usually immigrants) self-appointed “new masters”.

The Romanian village population also suffered from the new political conditions. There was tension between the peasants who had lived in the village for several generations and the Romanians who had moved here.

The policy of the new government in the People's Republic of Romania , determined by the Stalinist Soviet Union , also pushed through its goal in Girelsau to expropriate the peasants and appoint them as employees of the state agricultural production cooperatives ( Agricultural Production Cooperative LPG).

Churches and Christian denominations

Today there are four Christian denominations in the village, which are historically represented according to the available sources.

a) The oldest and source-based church on the site is that of the German settlers, who were Roman Catholic until the Reformation and belonged to the Sibiu chapter (deanery).

The church's patronage is not known, but some historians suggest that it was a “St. Gerhard “was. The pastors used the name "Plebanus de insula gerhardi", but never "de Fenyefalwa". They were only mentioned by their first names, which may indicate that they belonged to the Chapter Brotherhood in Sibiu. In a document in 1461, a “Symon plebanus de Insula Gerhardi iamdicti decanatus et capituli Cybiniensis confrater” (Symon, the pastor of Girelsau, named above as dean and brother of the Sibiu chapter) was mentioned. The pastor's office was entitled to 4 tenth quarters, later only three, which was a good endowment for the small village. The following pastors are recorded: since 1327 Nikolaus, Mathias, Johannes (2 ×), Nikolaus, Bartholomäus, Jacobus, Michael. After 1486 until the Reformation: Mathias, Johannes, Jakobus, Andreas, Johannes. 1525 Johannes Rain, Laurenzius Zipser.

After the Reformation (from Laurenzius Zipser) these continued to belong to the Sibiu Chapter and to the Reformation Church AB in Transylvania . As such, this denomination existed until the mass emigration of Saxony to Germany after 1989 and today has only a few members. You will be by Pastor i. R. Gerhard Kenst, who has his residence in the former rectory.

Numerous church flags and paraments from the 18th and 19th centuries have been preserved in the parish archive . These show a number of donors with the following surnames: Veber (mentioned in 1775, and Michael Veber is also recorded as the house owner on a stone house panel from 1736). The Latin spelling “Veber” instead of “Weber” is remarkable because the Latin Language doesn't know a "W". Other names are Brius, Drotleff, Krauss, Theil, Markus, Waadt, Modjesch, Nößner in addition to the well-known names such as Schieb, Atzmann etc.

The source of the church building can only be found in the 15th century. The previous church must have been a wooden church, where pastors are documented from 1337. In 1496 the construction of a new stone church building began, which lasted until 1538. A curtain wall was built around the church.

In 1600 the church building was destroyed by marauding soldiers from the troops of the Prince of Wallachia Mihai Viteazul (Michael the Brave) . The current church building is erected in 1633. The last exterior renovation took place in 2015.

The cemetery belonging to this parish is traditionally reserved for the Saxons.

b) The second oldest denomination is the Romanian church united with Rome and is mentioned as a subsidiary of Săcădate with 117 members from 1750 onwards . In the statistics of 1767 it does not appear as an independent parish.

According to oral tradition, there were disputes between supporters of the Orthodox Church and the Church united with Rome in Girelsau around 1759/60, but there are no sources about this. At the beginning of the 19th century there is said to have been a "church house" ("casă bisericescă"), then a wooden church was built. In 1805 there was an Orthodox branch with the pastor Iuoan Dumitru. As early as 1826, the parish under Pastor Nicolae Coman became a church united with Rome . In 1843, 50 families are listed as Orthodox Christians, but they are referred to as the “Filialgemeinde” of Săcădate / Sakadat, whereby the existing church was used alternately between the two denominations. After 1855 the parish is uniformly registered as a parish of the Church united with Rome. In 1884 a resolution of the community "Gierelsau" is documented, which the "elimination of a portio canonica for the gr.-cath. Parish ”, which was intended for the upkeep of the church building and the priest.

Thus the congregation united with Rome was a recognized congregation in Girelsau, which it will remain until the state dissolution of this church communion in 1948. Then the parish was incorporated into the Orthodox deanery (Protopopiat) Avrig / Freck. The last United Pastor was Ioan Oros.

After 1989 some parishioners want a return to the old tradition of the church united with Rome, which is now recognized again as the Romanian national church. The supporters of the Orthodox community resisted and there were serious disputes. At the request of both denominations, pastors were installed in the village who alternately held services in the church. There were considerations that after the emigration of the Saxons, the old Protestant church should be rented or bought by the Orthodox. This failed because of the resistance of the few remaining Saxons. Even the emigrated Saxons were not enthusiastic about such a solution and refused to hand over their former church to the Orthodox. Over the years the situation calmed down and the Christians Uniate Rome and the Orthodox celebrated their masses alternately in the church. But the Orthodox sought to build their own church.

The old church building was built between 1911 and 1913, when Pastor Demetriu M. Clain (1850–1927) served here. He was a member of the United Bishop Inocențiu Micu-Klein . The church, popularly known as "Biserica din Deal" (the church on the hill), is consecrated as "Biserica Adormirea Maicii Domnului" (Dormition of the Virgin).

The cemetery belonging to this parish serves all Romanian residents and the Roma.

The parish traditionally belongs to the Grand Archbishopric of Weißenburg and Fogarasch (Arhieparhia de Alba Iulia și Făgăraș ) and is currently looked after by Rev Ioan Crișan.

c) Today's Orthodox Parish “Sf. Împărați Constantin și Elena “(Holy Emperor Constantine and Empress Helena ) was founded after 1989. It is the largest Christian community in the village and sees itself as the successor to the orthodox parish founded by state power in 1947. It has a newly built church in the middle of the village, known as “Sf. Împărați Constantin și Elena “(Holy Emperor Constantine and Empress Helena) was consecrated.

Some of its members belong to the Orthodox Christians who were born after 1948 and who feel obliged to the Romanian Orthodox Church . Another part of this parish are the relatives of the Romanian immigrants after 1945 who came from Orthodox communities and traditionally see themselves as belonging to this church as the “Church of the Romanians”.

The parish belongs to the orthodox protopopiate Avrig / Freck and is under the jurisdiction of the Archdiocese of Sibiu of the Transylvanian Metropolis (Metropolia Ardealului) of the Romanian Orthodox Church.

She is looked after by Pastor Vasile Nichifor.

d) The third and youngest denomination is a smaller community of Baptists who also belong to the Romanian population. They were already active in the village before 1990, where they are incorrectly called "Pocăiți" in the village, which makes them appear as a Christian sect . You have a small church in "Winkel". Your small community is a branch of the Sibiu resident "Biserica Baptistă Speranța Sibiu (BCBSS)" (Baptist Church "Hope" Sibiu).

e) The church membership of the Roma living in Girelsau is open. They were denied access to the German Evangelical Lutheran Church AB in Girelsau in the past. The majority are baptized Christians and belong to the Romanian parishes. Others reject Christian baptism and live according to their own traditional beliefs.

School system

In the oldest surviving population census of the Seven Chairs from 1488, a " schoolmaster " is mentioned in the village. What such school education looked like in Girelsau has not been documented, but it probably took place in a modest framework, limited to the most necessary - depending on the profession and status - reading and writing. In the 17th century the Saxon school system in Transylvania was organized in such a way that, in addition to the 239 clergy, 224 headmasters were registered. Latin was learned in the village schools because it was the official language in the Principality of Transylvania. The situation changed when the Habsburgs introduced German as the official language in Transylvania in the 18th century . This made the language of a minority (12-15%) the official language, which led to great resentment among the Szeklers and Romanians, who in turn made up the majority in Transylvania. The school education situation remained tense because it was not clear who could and should act as the responsible school authority. The schools remained denominational. The Romanian students learned the Cyrillic alphabet by 1862 because Romanian used this spelling. With that they were barely able to find their way around the Latin script and it was a huge disadvantage for their education. It was not until 1862 that the Transylvanian-Romanian press switched to the Latin script. The emergence of the political national movements in Transylvania in the 19th century created a reorientation in school education, so that the different nationalities had their own schools, as in Girelsau. The churches of both nationalities played an important role in this: they were interested in maintaining traditional beliefs in their own language. On the Saxon side, the Evangelical Lutheran bishop and educator Georg Daniel Teutsch promoted elementary school instruction and a new school was built in Girelsau from 1852 to 1853.

Romanian classes took place in a house until the first Romanian school was built next to the church in 1890. The first and long-time teacher (1892-1932) was Nicolae If. Ursu.

The number of students was: in 1876 70 German and 63 Romanian students, in 1880 54 and 62 students, in 1900 73 and 55 and in 1922 91 and 93 students.

In 1878/79 Romanian pupils were also enrolled at the German school.

However, both nations were put to a severe test when the Budapest government in Austria-Hungary sought the Magyarization of the school system from 1867 . On the Romanian side, the establishment of the ASTRA People's Education Association was a great help, from which the Romanian villagers in Girelsau also benefited.

With the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy and the incorporation of Transylvania into the Kingdom of Romania , Romanian became the official language. The denominational elementary schools were retained.

A new, large school building was built in the village in 1936-37 and still serves as a school today.

The second school building was the German denominational school. In the years from 1939 to 1944, the German school was more and more appropriated by the national fascist “ renewal movement ” for its political purposes and stripped of its denominational significance. At the same time, a fascist-national way of thinking developed among the Romanians in the 1930s ( History of Romania ), which was now also noticeable in the schooling in the village after 1935. So the Romanian students had to join the organization "Straja Țării" and there the dictatorial ruling King Carl II . pay homage

The final abolition of the denominational schools in the village did not take place until 1948, when the school system was nationalized and education was ideologized with the aim of shaping the "new people" on the communist model. A German department was retained in both kindergarten and elementary school. In 1970 there were 50 Romanian and 25 German children in kindergarten, using the mother tongue of the respective ethnic group. There were 74 Romanian and 38 German children in primary school, with lessons in their respective mother tongue. In grades 5-8 there were a total of 215 students with Romanian as the language of instruction.

The old confessional traditions were pushed more and more to the sidelines and it is to the special merit of the educators, teachers and some tradition-conscious villagers that these lived on in a limited form with both the Saxons and the Romanians despite state difficulties in the village.

With the emigration of the Saxons (after 1990) there was no longer any need for a German school. The centuries-old German tradition of school is history. The former German school building was sold in favor of the last church renovation and is now privately owned.

Today's school in Girelsau is a grammar school according to European standards.

economy

In the Middle Ages, the village belonged to the Sibiu chapter and was determined accordingly by the economic order of the chapter. In the 14th century it had 12 hooves, in 1488 there were 43 farmsteads with a size of the district portion of 94 ha.

In addition to working the fields, the inhabitants of the village were engaged in fishing and fish trading as well as the timber industry. Larger craft businesses are not known.

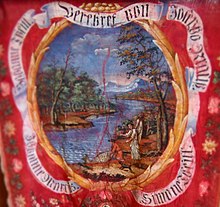

In 1494 Paulus Atzmann delivered fish for the state parliament in Sibiu. The fishing tradition in Girelsau is also documented on an old flag from 1775,

which possibly represents the village coat of arms. A cross and the crown of the Grand Duchy of Transylvania can be seen above a stylized representation of a hill with two crescent moon at the two outlets (similar branding) . The other parallel picture shows the river Alt, on one bank of which one can see vine tendrils on a hill and on the other wheat. In addition the text is to be read: "The dear youth in memory of 1775". On the back a man (fisherman) is shown pulling a large fish from the altar. A figure of an angel (guardian angel?) Can be seen behind him. On a tape around the depiction is written: "Adored by Josepho Krauss, Simone Theill, Johannes Marcus, Johanne Theill". This also attests to viticulture in Girelsau.

At the end of the 18th century we learned that Girelsau "is a beautifully built village in a pleasant area near the Old River, where the tastiest fish are caught from the stream".

In a communication from 1815 it says: “The nice, nicely built houses testify to the prosperity of the residents”, whereby a “chalk mountain” is also mentioned.

On an engraving from 1817 the imperial couple Franz the First and Karolina Augusta can be seen crossing the Old River on ferries near Girelsau, who paid a visit to Transylvania and thus also visited Girelsau.

It is perhaps thanks to this event that in the course of the improvement of the infrastructure in Transylvania in 1838 a wooden bridge was built over the Alt, which connected Girelsau to the road traffic from Sibiu to Kronstadt.

A large stagecoach station was built in Girelsau, the buildings of which are still preserved.

In 1885 the first Raiffeisen Association was founded in the village , which was now an important aid in supporting the Saxon economy in the village. In the 19th century, a M. Kraus founded a brick factory and built a small mill. Various craft trades can also be found in Girelsau in the 19th and 20th centuries, such as butchers, schumachers, bricklayers and blacksmiths, whereby these work for their own village needs. The carpenter's profession is practiced by Johann Müller, Johann Klein, Michael Bordon and Gheorghe Tatu, who are also involved in the construction of ferries across the Alt from the municipality. Agriculture and animal husbandry remain the main occupation of the villagers.

Girelsau has a total area of 5866 yoke in 1895, of which forest 2300 yoke, arable land 2508 yoke, meadow and hay areas 592 yoke, pasture areas 100 yoke, gardens 78 yoke and courtyard areas 130 yoke.

In 1908 a large iron bridge was built over the Alt, which went down in history as the "Girelsau Bridge" (Podul Bradului) as a special architectural work.

The village, however, remained characterized by agriculture and cattle breeding, even if its integration into the newly built so-called "Schwedenstrasse" between 1933 and 1938 promised economic success as part of the modernization of the infrastructure.

The agricultural products such as vegetables and meat products were sold on the market in Sibiu and the surrounding area.

At the end of the 1930s, “cooperatives” were also founded in Girelsau. The Romanian population founds the “Cooperativa de consum Brădeana”.

Even under the influence of the supporters of the German National Socialists, the Saxon farmers in Transylvania were to be organized into "cooperatives" and "local communities". A similarly named form of economy then prevailed under the new communist government when the farmers in Girelsau were registered in the "Gospodăria colectivă Olga Bancic" (collective cooperative Olga Bancic ) in 1958 . This was preceded by a great resistance from the Romanian peasantry, who only now understood that the expropriation and nationalization of the goods in the village would affect them too. Some Romanian farmers were arrested, others were tortured by the Securitate . The Legionari supporters living in the village hoped for the American occupation of Transylvania.

Nothing is known of resistance from the Saxon population. They must have given up and were hoping for a speedy emigration to Germany.

Both ethnic groups were forced to come to terms with the new communist economic order, but they never really accepted it. In the LPG ( agricultural production cooperative) they were now employees who had to work their own fields on the orders of the state organs. It was a kind of state serf situation because they got their wages in kind and little money. This finished the centuries-old farming business in Girelsau. The mismanagement, caused also by corruption and systematic theft of goods, took its course, whereby the theft was not understood as a crime, but as compensation for the goods “stolen” by the state.

The gardens around the house provided the opportunity to grow the household necessities, so that most of the families were self-sufficient from the disastrous state supply. The villagers supplied themselves with meat by taking pigs, cows, water buffalo, sheep, goats, rabbits, chickens and the like. a. held for personal use. The severely restricted private sector in the village was more efficient than that of the state production cooperative, which over the years degenerated into mismanagement.

In the course of the massive industrialization policy of the communist government, the young villagers were trained as factory workers, who were no longer willing to work in the fields as farmers in a planned agricultural economy , especially since wages in agriculture were much lower than in industry.

The Saxons in particular adapted quickly and were valued as sought-after construction and factory workers . So they no longer earned their livelihood as farmers, but as workers and state employees.

In 1990 the political situation changed and many villagers managed to get their fields back. But the peasant economic system and the traditions associated with it no longer existed. Based on the tragic experiences after 1945, only a few Saxons made use of the opportunity to get back land and most of them emigrated to Germany. A few have taken over the houses and gardens from their grandparents and let tenants or acquaintances manage them.

The Romanian population cultivates the arable and forest areas. Many young people work abroad or have set up their own companies locally to support their families. A new branch of the economy is tourism, which is slowly gaining momentum in the beautiful landscape. The newly created reservoir, which extends into the Girelsau area and is fed by the water of the old, is also ideal.

The village of Bradu is now part of the European Union and the villagers are already integrated into European economic policy.

Politically and administratively, the village today belongs to the city of Avrig, from which it is geographically separated by the Alt.

Attractions

- Evangelical church , built in 1633, probably in place of an older church from the 15th century.

- Old bridge on the national road towards Avrig.

- Cabana Fântânița Haiducului , hotel 1 km in the direction of Sibiu on the national road.

- Cabana Ghiocelul , accommodation

literature

- Vasile Balteșiu: Monografia satului Bradu , edited by Michael Weber with a foreword and an introduction (German-Romanian) by the editor, Breuberg 2017.

Web links and sources

- Girelsau at sevenbuerger.de

- Information on archaeological and historical sights (Romanian)

- Pictures from Gierelsau

- Website of the "HOG Girelsau"

Individual evidence

- ↑ Cf. Dumitru Popa: Villae, Vici, Pagi. Aşezările rurale din Dacia romană intercarpatică . Editura Econimică, Sibiu 2002.

- ↑ So Vasile Balteşiu: Monografia satului Bradu . Ed .: Michael Weber. Breuberg 2017.

- ^ Siebenbürgen Institut Online, abbr. UB (Hrsg.): Document book on the history of the Germans in Transylvania . ( Online ).

- ↑ Michael Weber: Introduction to the monograph on Girelsau . In: Michael Weber (ed.): Vasile Balteșiu, Monografia satului Bradu . Breuberg 2017, p. X-XIV .

- ↑ Michael Lebrecht: Attempt to describe the earth of the Grand Duchy of Transylvania . 2nd Edition. Sibiu 1804, p. 137 .

- ↑ Gernot Nussbächer: From "Tannendorf" to "Gerhardsau". From the local history of Girelsau . In: New Way Newspaper . Bucharest September 15, 1987, p. 4 .

- ^ Transylvania Institute online: Document book UB 467 .

- ^ Transylvania Institute online: Document book UB 537 .

- ^ Transylvania Institute online: Document book UB 514 .

- ^ Transylvania Institute online: Document book UB 1211 .

- ^ Transylvania Institute online: Document book UB 1725 and UB 1729 .

- ^ Transylvania Institute online: Document book UB 2157 .

- ↑ Gernot Nussbächer: From "Tannendorf" to "Gerhardsau" ...

- ↑ Gernot Nussbächer: On the local history of Girelsau . In: newspaper Karpatenrundschau . Volume 29, No. 37 . Kronstadt September 14, 1996, p. 3 .

- ↑ Cf. Konrad Gündisch: Transylvania and the Transylvanian Saxons . In: Study book series of the East German Cultural Council Foundation . tape 8 . Langen Müller, Munich 1998, p. 97 f .

- ↑ Nicolae Torgan: Material istoric privitor la alungarea Romanilor din Satele Sasesti . In: Transilvania . tape XXXI . Sibiu 1901, p. 98 .

- ↑ Vasile Balteşiu: Monografia satului Bradu . 2017, p. 176 f .

- ↑ Nicolae Torgan: Statistica Romanilor din Transilvania în 1733. Conscripţia episcopului Ioan Inocenţiu Micu Klein . In: Transilvania . tape XXX , no. 5 . Sibiu 1898, p. 169 ff .

- ↑ Augustin Bunea: Statistica Românilor din Transilvania în anul 1750, făcută de vicarul episcopesc Petru Aron . In: Transilvania . tape XXXII , no. IX . Sibiu 1901, p. 251 .

- ↑ Vasile Balteşiu: Monografia satului Bradu . 2017, p. 63 .

- ↑ Vasile Balteşiu: Monografia satului Bradu . 2017, p. 64 .

- ↑ Vasile Balteşiu: Monografia satului Bradu . 2017, p. 66 .

- ↑ Vasile Balteşiu: Monografia satului Bradu . 2017, p. 163 .

- ↑ Cf. Michael Wedekind: Science Mileus and Ethnopolitics in Romania in the 1930/40 Years . In: Josef Ehmer, Ursula Ferdinand, Jürgen Reulecke (Hrsg.): Promotion of the population. On the development of modern thinking about the population before, during and after the "Third Reich" . Wiesbaden 2007, p. 233-266 .

- ↑ Vasile Balteşiu: Monografia satului Bradu . 2017, p. 56 .

- ↑ Agneta Wenerich: "Girelsau" - We will not forget you . In: Manuscript unpublished . S. 3 .

- ↑ Vasile Balteşiu: Monografia satului Bradu . 2017, p. 57 (note 2) .

- ↑ See Annemarie Weber / Hannelore Baier: The Germans in Romania. A collection of sources. In: Writings on cultural studies in Transylvania . tape 35 . Böhlau, Cologne 2015, p. 125 ff .

- ↑ Ludwig Klaster: The Chapter Brotherhoods of the Evang. Church AB in Transylvania . In: Ulrich A. Wien (Ed.): Reformation, Pietism, Spirituality. Contributions to the Transylvanian-Saxon church history . tape 41 . Böhlau, Cologne 2011, p. 1-22 .

- ^ Transylvania Institute online: Document book UB 3252 .

- ^ Chronological index of the pastors of the Sibiu Chapter, from 1327 to the present day . In: Transylvania Provincial Papers . tape 3 . Martin Hochmeister, Hermannstadt 1808, p. 1 .

- ↑ H. Müller: brick fonts . In: Correspondence sheet of the Association for Transylvanian Cultural Studies . Sibiu 1885, p. 22 .

- ↑ Michael Weber: Evangelical Church in Girelsau with a new roof . In: Transylvanian newspaper . 65th year. Munich July 13, 2015.

- ↑ See Daniel Dumitru / Anja Dumitran / Florean-Adrian Laslo: "... virtuti de creati follenantiae benificia clero Graeci resttuenda ..." Biserica română din Transylvania în izvoarele statistice ale anului 1767 . Alba Iulia 2009.

- ↑ Vasile Balteşiu: Monografia satului Bradu . 2017, p. 202 .

- ↑ Sibiu Magistrate: Protocols . In: Siebenbürgisch-Deutsches Tageblatt . Volume 8, No. 123 . Sibiu 1884.

- ↑ Vasile Balteşiu: Monografia satului Bradu .

- ↑ Gernot Nussbächer: From "Tannendorf" to "Gerherdsau". From the local history of Girelsau .

- ↑ Katalin Peter: The heyday of the principality (1606-1660) . In: Béla Köpeczi (Ed.): Brief history of Transylvania . Budapest 1990, p. 344 .

- ↑ Zolt Trócsányi / Ambrus Miskolczy: Transylvania in the Habsburg Empire . In: Bela Köpeczi (Ed.): Brief history of Transylvania ... p. 438 ff .

- ^ Zoltan Szasz: Population, Economy and Culture in the Age of Capitalism . In: Bela Köpeczi (Ed.): Brief history of Transylvania ... p. 588 .

- ↑ Vasile Balteşiu: Monografia satului Bradu . 2017, p. 175 f .

- ↑ Vasile Balteşiu: Monografia satului Bradu . 2017, p. 182 .

- ↑ Vasile Balteşiu: Monografia satului Bradu . 2017, p. 181 .

- ↑ Vasile Balteşiu: Monografia satului Bradu . 2017, p. 180 .

- ↑ Vasile Balteşiu: Monografia satului Bradu . 2017, p. 187 .

- ^ Paul Niedermaier: Cities, Villages, Architectural Monuments. Studies on the settlement and building history of Transylvania . In: Studia Transylvanica . Böhlau, Cologne 2008, p. 102 .

- ↑ Gernot Nussbächer: From "Tannendorf" to "Gerhardsau". From the local history of Girelsau ...

- ↑ Parish AB Girelsau: Archives of the Evangelical Lutheran parish AB Girelsau . Girelsau 2015.

- ↑ Michael Lebrecht: Attempt to describe the earth ...

- ↑ Letters from Transylvania . In: Renewed patriotic sheets for the Austrian imperial state . Vienna 1815, p. 167 .

- ↑ Vasile Balteşiu: Monografia satului Bradu . 2017, p. 157 .

- ↑ Vasile Balteşiu: Monografia satului Bradu . 2017, p. 156 .

- ↑ Vasile Balteşiu: Monografia satului Bradu . 2017, p. 158 f .

- ↑ The Carpathians . No. 7 . Sibiu 1910, p. 404 .

- ↑ Vasile Balteşiu: Monografia satului Bradu . 2017, p. 117 .

- ↑ Vasile Balteşiu: Monografia satului Bradu . 2017, p. 117 ff .

- ↑ Vasile Balteşiu: Monografia satului Bradu . 2017, p. 124 .

- ↑ Vasile Balteşiu: Monografia satului Bradu . 2017, p. 157 f .

- ↑ Cf. Nils Hakan Măzgăreanu: The construction of the "Schwedenstraße" 1931 to 1938 . In: Journal for Transylvanian Cultural Studies . No. 26 (97) , 2003, pp. 184-190 .

- ↑ Vasile Balteşiu: Monografia satului Bradu .

- ^ Johann Böhm: National Socialist Indoctrination of Germans in Romania 1932-1944 . Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2008, p. 130 ff .

- ↑ Vasile Balteşiu: Monografia satului Bradu .