Cluster headache

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| G44.0 | Cluster headache |

| IHS / ICHD-III code | 3.1 |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

The cluster headache ( English cluster 'group', 'accumulation') is a primary headache disease . It manifests itself among other things by a strictly one-sided and occurring in attacks, extremely violent pain in the temple and eye area. The term cluster refers to the common characteristic of this form of headache, which occurs periodically with a high frequency. Symptom-free intervals can then follow for months to years.

The disease is also known under the names Bing-Horton neuralgia , histamine headache, cluster headache (CH; English headache 'headache'), suicide headache and erythroprosopalgia ( ancient Greek ἐρυθρός 'red'; πρόσωπον 'face'; ἄλγος 'pain').

Symptoms

The attacks usually last between 15 and 180 minutes and occur suddenly, primarily during sleep. The pain is always on the same side in 78% of patients. The cluster headache shows a pronounced daily rhythm . Seizures are most common one to two hours after falling asleep, in the early hours of the morning, and after noon. The frequency is between one attack every other day and eight attacks a day.

The pain is described as unbearable, tearing, piercing and sometimes burning. It usually occurs around the eye, less often in the temples and back of the head. An urge to move around, physical restlessness or agitation that exist during the headache attacks are particularly typical. Patients often wander or rock their upper bodies during a cluster attack, while patients with migraines are more likely to retire to bed. A subset of patients reported mild background pain between attacks.

In addition to pain, at least one of the following accompanying symptoms occurs on the painful side of the head:

- reddened conjunctiva of the eye ( conjunctival injection ) and / or a watery eye ( lacrimation )

- runny and / or blocked nose (nasal rhinorrhea and / or congestion )

- an eyelid edema

- Sweating of the forehead or face

- constricted pupil ( miosis ) and / or a drooping eyelid ( ptosis )

Also nausea , light and sound sensitivity occur regularly. A quarter of patients experience an aura before the attack , which makes it difficult to distinguish it from migraine. Unilateral autonomic accompanying symptoms are also not specific to cluster headache and can also occur with migraine attacks. Around 3% to 5% of those affected by cluster headache do not have any accompanying autonomic symptoms.

A distinction is made between episodic cluster headache (ECH) with remission phases of a few months to several years from chronic cluster headache (CCH) with remission phases of a maximum of three months. The definition of the duration of the remission periods for the differentiation was increased from one month to three months with the 3rd edition of the International Classification of Headache Diseases (IHS ICHD-III) in January 2018. The episodic cluster headache is the more common variant at around 80%.

A symptomatic cluster headache, also called a secondary cluster headache, shows the same symptoms as the primary cluster headache, but is the result of a different disease. In this way, masses lying close to the center line such as z. B. tumors , infarct areas or inflammatory plaques and lesions in the area of the brain stem , such. B. angiomas , pituitary adenomas or aneurysms , but also infectious diseases trigger symptomatic attacks similar to cluster headache. This symptomatic cluster headache is often difficult to distinguish from the primary form. The drugs verapamil , oxygen or sumatriptan used to treat the primary cluster headache are also effective in symptomatic cluster headaches, but these drugs have no effect on the actual causes of the secondary cluster headache.

Strength of pain

The pain during a cluster headache attack, along with trigeminal neuralgia, is one of the most severe pain imaginable for humans. It is often given on a pain scale from 0 to 10 with the highest level. Female patients describe individual attacks as worse than the pain in childbirth.

Epidemiology

The frequency of cluster headaches ranges from 0.1% to 0.15% of the population. Men are affected more often than women in a ratio of 4.3 to 1. Hereditary factors are not yet known, but a familial burden of around two to seven percent is assumed. The disease often begins in the 28th – 30th Year of life, but can also start in any other year of life. Usually up to 80% of patients still suffer from cluster headache episodes after 15 years. However, the pain disappears ( remedies ) in some older patients. In up to 12%, a primary-episodic form changes into a chronic form; the reverse is less common.

root cause

The causes of the cluster headache are not clear. An enlargement or inflammation of the blood vessels does not seem to be the cause of the headache, as previously assumed, but rather its consequence. Further investigations did not reveal any signs of inflammation in the cavernous sinus . Certain pain-conducting pathways in the area of the trigeminal nerve are stimulated by as yet unknown influences . This leads to a cascade of changes in the brain metabolism. It is believed that the "motor" of the disease lies in the hypothalamus . This "control center" of the diencephalon controls important control circuits, for example the sleep-wake rhythm and blood pressure. The diurnal distribution patterns of the pain attacks, the noticeable frequency of episodes in spring and autumn as well as frequent disturbances of hormones that control the daily rhythm, for example melatonin, speak for a disruption in these control loops . The results of imaging procedures bring a subunit of the hypothalamus, the hypothalamic gray, into the focus of current scientific studies.

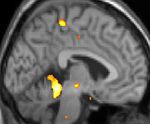

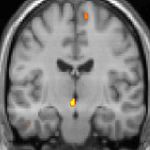

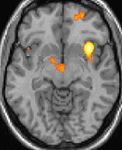

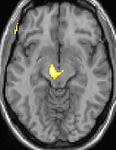

| This PET of the brain superimposed on a magnetic resonance tomography shows increased activity in the pain matrix and in the hypothalamus on the right | ||

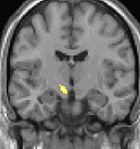

| This magnetic resonance tomography with drawn morphometry shows a higher proportion of gray matter in the hypothalamus on the right (left in the picture) | ||

The positron emission tomography (PET) representations above show the functional data, i.e. the areas that show activity when there is pain, compared to the appearance with a pain-free interval. You can see the so-called pain matrix, which is always activated when there is pain, and the area in the middle (in all 3 levels), which is specifically activated in the cluster headache. The VBM images below show the structural data. This examines whether the brains of cluster headache patients are different from the brains of people without a headache. Only one area is different, it contains more gray matter : This corresponds to the functional area shown above. It is the hypothalamus. Among other things, the sleep-wake rhythm is generated there. It is therefore believed that the motor of cluster headache is located in the hypothalamus. With the 1 H magnetic resonance spectroscopy , biochemical differences between the hypothalamus of healthy people and the hypothalamus of cluster headache patients could also be detected.

According to research from October 2014, however, it is assumed that the disease is caused by a network disorder and not just by the hypothalamus. Gray matter changes in the areas of pain processing and beyond were identified in patients with cluster headache compared to healthy individuals. These gray matter changes were significantly different for chronic and episodic cluster headache, as well as within and outside of the episode. A decrease in gray matter was primarily observed in chronic cluster headache, while episodic cluster headache showed a more complex and sometimes opposite pattern. These dynamics likely reflect the brain's adaptability to changing stimuli related to cortical plasticity and could explain the different results of previous VBM studies on pain.

diagnosis

The diagnosis is made by the Medical history and because of the specific symptoms . These are defined in the IHS / ICHD-III classification (International Classification of Headache Disorders) Version 3.1. Special laboratory test methods are not available. So cluster headache is a condition that is diagnosed according to the patient's instructions. Imaging and other examination methods do not contribute to the diagnosis, but can only rule out other diseases. With the help of cranial computed tomography (CCT), magnetic resonance tomography , Doppler sonography and electroencephalography (EEG), other causes for the complaints, such as tumors , cerebral hemorrhage and inflammation, can then be determined. In the differential diagnosis, a distinction must also be made between cluster headache and other forms of headache such as migraine , tension headache , trigeminal neuralgia , paroxysmal hemicrania (CPH) and hemicrania continua . Electrophysiological , chemical laboratory and CSF examinations usually do not help in confirming the diagnosis of cluster headache diagnostically.

Trigger for cluster attacks

The attacks can be triggered by certain factors. But they are not the actual cause of the disease. Well-known triggers are, for example, alcohol , histamine and glycerol trinitrate . Patients also report flickering light and glaring light. Noise , food additives such as glutamate , potassium nitrite and sodium nitrite , but also odors such as solvents, gasoline, adhesives, perfume or the consumption of cheese , tomatoes , chocolate and citrus fruits are named as triggers. Other possible triggers: heat, daytime sleep, prolonged exposure to chemicals, extreme outbursts of anger or emotions, prolonged physical exertion, large changes in altitude, and the drug sildenafil . The drug lithium used for preventive treatment can also trigger attacks in individual cases.

The effect of the various trigger factors is very different for each patient. Some patients do not respond to any of the above triggers.

Therapy and prophylaxis

Cluster headache is a condition that cannot be cured by medical treatment. The intensity of the pain attacks and the frequency of the attacks can often be reduced by appropriate treatment. As with all recurring headaches, it is useful to keep a headache diary . This makes diagnostics easier for the doctor, is used to monitor therapy and can help to identify the triggers of pain attacks.

Acute treatment

- Inhalation of 100% medical oxygen via a high-concentration mask (non-rebreather mask) with a reservoir bag and non-return valves. Other breathing masks are less effective. The required flow rate is between 7 and 15 l / min. over a period of 15 to 20 minutes. Oxygen cannula are not suitable, as those affected usually cannot breathe through their nose during the attacks. In addition, the required flow rate cannot be achieved with oxygen cannula. Oxygen concentrators are also unsuitable as they only have a maximum flow rate of 5.5 l / min. to reach. Medical oxygen suitable for the treatment is available in pressurized gas cylinders ( oxygen cylinders ).

- Triptans : Sumatriptan subcutaneous and zolmitriptan nasal are approved for the acute treatment of cluster headaches.

- Sumatriptan nasal spray is recommended by the German Society for Neurology as the “second choice”, as is the intranasal supply of four to ten percent lidocaine nasal drops.

Inhaling pure oxygen at a flow rate of 12 liters per minute and using a high-concentration mask (non-rebreather mask) ends a cluster headache attack within 15 minutes in 78% of cases and has no side effects. The use of lidocaine only helps a part of the patients and also not them in every pain attack. Octreotide can be used to treat cluster headache attacks when other drugs are ineffective or contraindicated.

For since 2011 practiced SPG stimulation is through an incision in the gum a neurostimulator on pterygopalatine ganglion used (sphenopalatine ganglion). During the operation, the device is attached to the upper jaw with two bone screws and the electrode tip is placed on the pterygopalatine ganglion behind the cheekbone. As soon as a cluster headache attack occurs, the patient stimulates the implant inductively via a control device that he holds on the outside of the cheek. The abbreviation SPG stands for sphenopalatine ganglion . In a multicenter, randomized study, the primary endpoint of the study, pain relief from attacks in less than 15 minutes, could only be achieved in a small proportion of the 28 study participants . Only seven of the 28 participants achieved pain relief in less than 15 minutes in more than 50% of the attacks treated. Severe side effects occurred in five cases, and most patients (81%) experienced mild or moderate temporary loss of sensation in various maxillary nerve regions. 65% of the adverse events were resolved within three months.

Preventive treatment

For chronic and episodic cluster headache, the preventive drug of first choice is the prescription drug verapamil . Before the first use, when increasing the dose and when using high doses, heart rate controls ( ECG ) are required. The drug is well tolerated in the long term. However, if the dose is increased gradually, the effect will only appear after two to three weeks. Because of the more even delivery of the active ingredient, the retarded form of the drug should be preferred. Both the retarded and the normal form of the drug are effective; there are no direct comparative studies on this.

Corticosteroids , ergotamine, or long-acting triptans such as naratriptan and frovatriptan can be used for short-term prophylaxis until another preventive therapy takes effect, or for short episodes. Because of their side effects, corticosteroids should not be taken permanently (<4 weeks), but rather as a bridging therapy until verapamil takes effect. Because of possible interactions , no other triptans may be used for acute treatment during preventive treatment with ergotamine or with long-acting triptans.

| First choice means |

| Verapamil up to 960 mg, ECG control |

| Corticosteroids 100 mg possibly higher dose |

| Second choice means |

| Lithium according to mirror |

| Topiramate 100-200 mg |

The lithium salts lithium acetate and lithium carbonate are the only drugs approved in Germany for the preventive treatment of cluster headaches according to pharmaceutical law. The lithium is the preventive treatment of second choice for cluster headache because of possible side effects. If verapamil and lithium salts fail, the prescription substances topiramate , pizotifen , melatonin or valproic acid can be tried . If a substance alone does not work, a combination can be tried under medical supervision.

Most patients can be helped with the above medication according to the guidelines of the German Society for Neurology . The US guidelines for the treatment of cluster headache contain other possible drugs. Current research and clinical practice occasionally discover additional agents that are effective against cluster headache. The use of gabapentin as an additional drug showed some success in a small study. The preventive treatment of five cluster headache patients with only three oral ingestion of the non- hallucinogenic 2-bromo-LSD within ten days was also successful .

In some cases, unspecific blockade of the major occipital nerve (large occipital nerve) with a local anesthetic and corticosteroids is successful and should therefore be attempted before surgical therapy. Also non-invasively is endoscopic blockade of the pterygopalatine ganglion using local anesthetic and corticosteroids .

Only after all drug measures have failed, surgical procedures should be considered in absolutely exceptional cases. However, their risks often outweigh the benefits. In the case of cluster headache, we advise against the radiation of the entry zone of the trigeminal nerve ( gamma knife ), which is known from the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia . A new, experimental preventive method is occipital nerve stimulation using electrodes implanted in the neck area . Another, still experimental, preventive procedure is deep brain stimulation . The disturbed structures are influenced by means of permanently implanted electrical probes in the hypothalamus . Established in the therapy of Parkinson's disease (paralysis) for a number of years, this procedure is an option for patients with chronic disease who cannot be helped in any other way.

Treatment in children and adolescents

In analogy to adults, acute therapy with oxygen inhalation or with subcutaneous or nasal triptans is recommended for children and adolescents with cluster headache. Oral verapamil or cortisone shock treatment are recommended for prophylaxis. Sumatriptan (10 mg) and zolmitriptan nasal spray are approved for acute treatment in adolescents aged 12 years and over.

Complementary and alternative medicine

Self-treatment does not make sense for cluster headaches because the medication is only available on prescription and has to be tailored to individual needs. There are no clinical studies on their effectiveness against cluster headache for the following drugs .

Among other things, patients report positive effects from:

- Change of diet to a purine and / or histamine reduced diet

- Drink plenty of water

- Taking vitamin B and / or vitamin D3 supplements

- Ingestion of minerals such as B. Magnesium

- Drinking energy drinks for attack docking

- Taking taurine supplements

- Taking minocycline

- Taking extracts or tea from the kudzu plant

- the psychedelics psilocybin , LSA or LSD .

Ineffective treatment

Usual analgesics, be it opioid analgesics such. B. morphine, tramadol, fentanyl or non - opioid analgesics such. B. acetylsalicylic acid , diclofenac , ibuprofen , metamizole or paracetamol are ineffective in the therapy of acute pain attacks. Since cluster headache attacks can resolve spontaneously after thirty to sixty minutes, it is mistakenly believed that this resolution is achieved through the use of an analgesic. Without efficacy also are carbamazepine , phenytoin , beta-blockers , antidepressants , MAO inhibitors , antihistamines , biofeedback , acupuncture , neural therapy , local anesthetics , physical therapy , surgical procedures and all forms of psychotherapy .

New developments

In a phase II study for the preventive treatment of episodic cluster headache, galcanezumab was used as a humanized monoclonal antibody that is a selective inhibitor of CGRP (`` calcitonin gene-related peptide ''). In this double-blind, randomized study , 300 mg galcanezumab or placebo were injected subcutaneously twice four weeks apart in patients with at least one headache episode every two days for at least six weeks. This reduced the weekly number of headache attacks in the first three weeks by a mean 8.7 attacks (versus 5.2 in the placebo group) and 71% (versus 53%) had at least a half the frequency of headache attacks after three weeks. There were no serious adverse effects , but 8% of patients on galcanezumab reported pain at the injection site. Since galcanezumab only has a concentration of 0.1% of the plasma concentration in the CSF due to the blood-brain barrier , this indicates a peripheral effect outside the central nervous system , such as B. on the trigeminal ganglion .

history

The ancient Greek and Roman literature mentions various headache disorders but does not contain any specific references to patients with a cluster headache. The Dutch doctor Nicolaes Tulp described two different types of recurring headache in the "Observationes Medicae" published for the first time in 1641: The migraine and probably the cluster headache:

“In the beginning of the summer season, [he] was afflicted with a very severe headache, occurring and disappearing daily on fixed hours, with such intensity that he often assured me that he could not bear the pain anymore or he would succumb shortly. For rarely it lasted longer than two hours. And the rest of the day there was no fever, not indisposition of the urine, no any infirmity of the pulse. But this recurring pain lasted until the fourteenth day […] He asked nature for help, […] and lost a great amount of fluid from the nose [… and] was relieved in a short period of time […]. ”

Probably Thomas Willis also described the disease cluster headache in 1672 in addition to the migraine.

Gerard van Swieten , the personal physician of Maria Theresa of Austria and founder of the Vienna Medical School, documented a case of episodic headache in 1745. This description meets the diagnostic criteria of the International Headache Society (IHS-ICHD-III Classification 3.1) for the presence of a cluster headache:

“A healthy robust man of middle age [was suffering from] troublesome pain which came on every day at the same hour at the same spot above the orbit of the left eye, where the nerve emerges from the opening of the frontal bone; after a short time the left eye began to redden, and to overflow with tears; then he felt as if his eye was slowly forced out of its orbit with so much pain, that he nearly went mad. After a few hours all these evils ceased, and nothing in the eye appeared at all changed. "

In 1840 Moritz Heinrich Romberg described ciliary neuralgia as a recurrent pain in the eye with reddened conjunctiva and constriction of the pupil. The Sluder neuralgia , named after the American otolaryngologist Greenfield Sluder (1865-1928), is a 1908 proposed, meanwhile controversial explanation for certain facial neuralgia . Sluder believed that the pterygopalatine ganglion (formerly known as the sphenopalatine ganglion ) mediates reflex irritation of the immediately adjacent branches of the trigeminal nerve . This ganglion is a parasympathetic nerve node under the base of the skull behind the roof of the mouth. He treated trigeminal neuralgia by injecting alcohol into this ganglion. In the current literature, sluder neuralgia is seen as a manifestation of cluster headache.

In 1926, the London neurologist Wilfred Harris (1869-1960) created the first complete description of cluster headache and called this periodic migraine neuralgia. In 1936 he referred to the same disease as ciliary (migranous) neuralgia. Harris was probably the first to correctly identify the "cluster" phenomenon. He treated patients with partial success by injecting alcohol into the gasserian ganglion . This is part of the trigeminal nerve. In 1937 he also reported that the subcutaneous injection of ergotamine tartrate ended the pain attacks as quickly as possible.

The Vidianusneuralgie (see nerve pterygoid canal ) was defined by Vail in 1932 as a recurring, one-sided severe pain to nose, eye, face, neck and shoulder in recurrent episodes.

The multiple new descriptions and new discoveries of cluster headache resulted in a large number of synonyms and confusion with other diseases that have no connection with cluster headache. Formerly used terms according to the IHS-ICHD-III classification: ciliary neuralgia, erythromelalgia of the head, Bing erythroprosopalgia, hemicrania angioparalytica, hemicrania periodica neuralgiformis, histamine headache, Horton's syndrome, Harris-Horton's neuralgia according to Gardner's peturalgia, migrainous neuralgia , Sluder neuralgia, sphenopalatine ganglion neuralgia, and vidian neuralgia. The term "Bing-Horton syndrome" can be found in the International Classification of Diseases ( ICD-10 ) G44.0 Cluster headache. The terms “suicide headache” or “suicide headache” are occasionally used and cannot be substantiated by an above-average number of suicides committed.

Only after the detailed description of the disease by Bayard Taylor Horton (1895-1980) and by the Basel neurologist Robert Bing (1878-1956), the disease acquired in the mid-20th century under the name of cluster headache , and later Bing-Horton syndrome a wider brand awareness.

“Our patients were disabled by the disorder and suffered from bouts of pain from two to twenty times a week. They had found no relief from the usual methods of treatment. Their pain was so severe that several of them had to be constantly watched for fear of suicide. Most of them were willing to submit to any operation which might bring relief. "

In 1947 Ekbom described the periodic occurrence of the attacks. The term “cluster headache” was first used in 1952 by Kunkle. In 1962 the cluster headache was included in the classification of headache disorders of the Ad Hoc Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS).

See also

literature

- Guideline cluster headache and trigeminal autonomic headache . Published by the guidelines commission of the German Society for Neurology , the German Migraine and Headache Society , the Austrian Society for Neurology , the Swiss Neurological Society and the Professional Association of German Neurologists . Status: May 14, 2015, valid until May 13, 2020.

- Charly Gaul, Hans-Christoph Diener, Oliver M. Müller: Cluster headache: clinical picture and therapeutic options . In: Dtsch Arztebl Int . No. 108 (33) , 2011, pp. 543-549 , doi : 10.3238 / arztebl.2011.0543 .

- Volker Limmroth: headache and facial pain . Schattauer, 2007, ISBN 978-3-7945-2319-1 .

- E. Leroux, A. Ducros: Cluster headache. In: Orphanet J Rare Dis. 23, No. 3, 2008, p. 20. PMID 18651939 , PMC 2517059 (free full text).

- A. May, M. Leone, J. Áfra, M. Linde, PS Sándor, S. Evers, PJ Goadsby: EFNS guidelines on the treatment of cluster headache and other trigeminalautonomic cephalalgias. In: European Journal of Neurology. 13, 2006, pp. 1066-1077. PMID 16987158 , efns.org (PDF) doi: 10.1111 / j.1468-1331.2006.01566.x .

- Ottar Sjaastad: Cluster Headache Syndrome . WB Saunders, London 1992, ISBN 0-7020-1554-7 .

Web links

- Cluster headache, information for patients. (PDF; 27 kB) German Migraine and Headache Society, July 2005

- How are cluster headaches and trigeminal autonomic headaches treated? German Migraine and Headache Society

- Guideline for the diagnosis, therapy and prophylaxis of cluster headaches, other trigeminal autonomic headaches, sleep-related headaches and idiopathic stabbing headaches . (PDF; 186 kB) German Migraine and Headache Society

- Neurology Clinic at the Cologne-Merheim Clinic: Cluster headaches

- Patient information cluster headache. CK knowledge wiki

multimedia

- DocCheck® TV: Arne May - Pathophysiology: "Where does the cluster come from and why is it there?"

- DocCheck® TV: Stefan Evers - Cluster headache differential diagnoses

- DocCheck® TV: Tim Jürgens - Cluster headache treatment - “Guideline-based therapy of the cluster. Often propagated, not so often done. "

- DocCheck® TV: Charly Gaul - "Acute therapy and prophylaxis of cluster headaches."

- DocCheck® TV: Zaza Katsarava - "Background, method and results of occipitalis stimulation for cluster headache: A new option in therapy?"

- DocCheck® TV: Arne May - "What to do if the guideline therapy does not work?"

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS): The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition . In: Cephalalgia . tape 38 , no. 1 , January 2018, p. 1-211 , doi : 10.1177 / 0333102417738202 , PMID 29368949 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k guideline for cluster headache and trigeminal autonomic headache . Published by the guidelines commission of the German Society for Neurology , the German Migraine and Headache Society , the Austrian Society for Neurology , the Swiss Neurological Society and the Professional Association of German Neurologists . Status: May 14, 2015, valid until May 13, 2020; Retrieved June 2, 2015.

- ^ A b c d e f A. May, S. Evers, A. Straube, V. Pfaffenrath, HC Diener: Therapy and prophylaxis of cluster headaches and other trigemino-autonomic headaches. Revised recommendations of the German Migraine and Headache Society . In: pain . tape 19 , no. 3 , June 2005, p. 225-241 , doi : 10.1007 / s00482-005-0397-8 , PMID 15887001 . DMKG ( Memento from November 6, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF)

- ↑ M. Schurks et al. a .: Cluster headache: clinical presentation, lifestyle features, and medical treatment. In: Headache. 46 (8), 2006, pp. 1246-1254. PMID 16942468 .

- ↑ PJ Goadsby: , injection lacrimation conjunctival, nasal symptoms ... cluster headache, migraine and cranial autonomic symptoms in primary headache disorders - what's new? In: J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry . tape 80 , no. 10 , 2009, p. 1057-1058 , doi : 10.1136 / jnnp.2008.162867 , PMID 19762895 .

- ↑ H. Guven, AE Cilliler, SS Comoğlu: Unilateral cranial autonomic symptoms in patients with migraine . In: Acta Neurol Belg . November 2012, doi : 10.1007 / s13760-012-0164-4 , PMID 23160810 .

- ↑ K. Ekbom: Evaluation of clinical criteria for cluster headache with special reference to the classification of the International Headache Society. In: Cephalalgia . tape 10 , no. 4 , August 1990, p. 195-197 , doi : 10.1046 / j.1468-2982.1990.1004195.x , PMID 2245469 .

- ↑ TH Lai, JL Fuh, SJ Wang: Cranial autonomic symptoms in migraine: characteristics and comparison with cluster headache. In: J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry . tape 80 , no. 10 , October 2009, p. 1116–1119 , doi : 10.1136 / jnnp.2008.157743 , PMID 18931007 .

- ↑ J. Tobin, S. Flitman: Cluster-like headaches associated with internal carotid artery dissection responsive to verapamil . In: Headache . tape 48 , no. 3 , March 2008, p. 461-466 , doi : 10.1111 / j.1526-4610.2007.01047.x , PMID 18302704 .

- ↑ F. Then Bergh, T. Dose, S. Förderreuther, A. Straube: Symptomatic cluster headache - expression of an MS flare-up with magnetic resonance imaging evidence of a pontomedullary lesion of the ipsilateral trigeminal nucleus . In: Neurologist . tape 71 , no. December 12 , 2000, pp. 1000-1002 , doi : 10.1007 / s001150050698 , PMID 11212852 .

- ↑ EC Leira, S. Cruz-Flores, RO Leacock, SI Abdulrauf: Sumatriptan can alleviate headaches due to carotid artery dissection . In: Headache . tape 41 , no. 6 , June 2001, p. 590-591 , doi : 10.1046 / j.1526-4610.2001.041006590.x , PMID 11437896 .

- ↑ Roland Schenke: Cluster: The worst headache in the world. In: odysso. SWR-Fernsehen, December 10, 2014, accessed on May 26, 2016 .

- ↑ Pain scale - CK knowledge. In: ck-wissen.de. Retrieved May 26, 2016 .

- ↑ Manjit S Matharu, Peter J Goadsby: Cluster headache: focus on emerging therapies . In: Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics . 4, No. 5, 2014, pp. 895-907. doi : 10.1586 / 14737175.4.5.895 . PMID 15853515 .

- ↑ M. Fischera, M. Marziniak, I. Gralow, S. Evers: The incidence and prevalence of cluster headache: a meta-analysis of population-based studies. . In: Cephalalgia . 28, No. 6, June 2008, pp. 614-8. doi : 10.1111 / j.1468-2982.2008.01592.x . PMID 18422717 .

- ^ MB Russell: Epidemiology and genetics of cluster headache. In: Lancet Neurol. 3 (5), 2004, pp. 279-283. PMID 15099542 .

- ↑ L. Piselli et al. a .: Genetics of cluster headache: an update. In: J Headache Pain. 6 (4), 2005, pp. 234-236. PMID 16362673 .

- ↑ a b A. May: A review of diagnostic and functional imaging in headache. In: J Headache Pain . tape 7 , no. 4 , September 2006, p. 174-184 , doi : 10.1007 / s10194-006-0307-1 , PMID 16897620 .

- ^ MJ Gawel, A. Krajewski, YM Luo, M. Ichise: The cluster diathesis . In: Headache . tape 30 , no. 10 , October 1990, p. 652-655 , doi : 10.1111 / j.1526-4610.1990.hed3010652.x , PMID 2272816 .

- ↑ H. Göbel, N. Czech, K. Heinze-Kuhn, A. Heinze, W. Brenner, C. Muhle, WU Kampen, A. Henze: Evidence of regional plasma protein extravagation in cluster headache using Tc-99m albumin SPECT. In: Cephalalgia. 20 (4), May 2000, p. 287. Congress report (abstract). doi: 10.1046 / j.1468-2982.2000.00204.x

- ^ S. Schuh-Hofer, M. Richter, H. Israel, L. Geworski, A. Villringer, DL Munz, G. Arnold: The use of radiolabelled human serum albumin and SPECT / MRI co-registration to study inflammation in the cavernous sinus of cluster headache patients. In: Cephalalgia . tape 26 , no. 9 , September 2006, p. 1115-1122 , doi : 10.1111 / j.1468-2982.2006.01170.x , PMID 16919062 .

- ↑ J. Sianard-Gainko, J. Milet, V. Ghuysen, J. Schoenen: Increased parasellar activity on gallium SPECT is not specific for active cluster headache. In: Cephalalgia. 14 (2), Apr 1994, pp. 132-133. PMID 8062351 .

- ↑ A. Steinberg, R. Axelsson, L. Ideström, S. Müller, AI Nilsson Remahl: White blood cell SPECT during active period of cluster headache and in remission. In: Eur J Neurol . July 2011, doi : 10.1111 / j.1468-1331.2011.03456.x , PMID 21771198 .

- ↑ a b P. J. Goadsby: Pathophysiology of cluster headache: a trigeminal autonomic cephalgia. In: Lancet Neurol. 1 (4), 2002, pp. 251-257. PMID 12849458 .

- ↑ a b c d Cluster headache, information for patients (PDF; 27 kB) German Migraine and Headache Society, July 2005.

- ↑ May u. a .: PET and MRA findings in cluster headache and MRA in experimental pain. In: Neurology. 55, 2000, pp. 1328-1335. PMID 11087776 .

- ^ AF Dasilva, PJ Goadsby, D. Borsook: Cluster headache: a review of neuroimaging findings. In: Curr Pain Headache Rep. 11 (2), 2007, pp. 131-136. PMID 17367592 .

- ↑ Lodi et al. a .: Study of hypothalamic metabolism in cluster headache by proton MR spectroscopy. In: Neurology. 66 (8), 2006, pp. 1264-1266. PMID 16636250 .

- ↑ Wang et al. a .: Reduction in hypothalamic 1H-MRS metabolite ratios in patients with cluster headache. In: J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 77 (5), 2006, pp. 622-625. PMID 16614022 .

- ^ S. Naegel, D. Holle, N. Desmarattes, N. Theysohn, HC Diener, Z. Katsarava, M. Obermann: Cortical plasticity in episodic and chronic cluster headache . In: Neuroimage Clin . tape 6 , 2014, p. 415-423 , doi : 10.1016 / j.nicl.2014.10.003 , PMID 25379455 . - Open Access.

- ↑ blue u. a .: A new cluster headache precipitant: increased body heat. In: Lancet. 354 (9183), Sep 18, 1999, pp. 1001-1002. PMID 10501368 .

- ^ A b D. Biondi, P. Mendes: Treatment of primary headache: cluster headache. ( Memento June 7, 2011 on WebCite ) In: Standards of care for headache diagnosis and treatment. US National Headache Foundation, Chicago (IL) 2004, pp. 59-72. US National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC). 2004

- ↑ de L. Figuerola et al. a .: Cluster headache attack due to sildenafil intake. In: Cephalalgia. 26 (5), May 2006, pp. 617-619. PMID 16674772

- ↑ RW Evans: Sildenafil can trigger cluster headaches. In: Headache. 2006 Jan; 46 (1), pp. 173-174, doi: 10.1111 / j.1526-4610.2006.00316_4.x , PMID 16412168 .

- ↑ Brainin et al. a .: Lithium-triggered chronic cluster headache. In: Headache. 1985 Oct; 25 (7), pp. 394-395, doi: 10.1111 / j.1526-4610.1985.hed2507394.x , PMID 3935601

- ↑ Press release of the German Migraine and Headache Society of May 21, 2001.

- ↑ L. Fogan: Treatment of cluster headache. A double-blind comparison of oxygen v air inhalation. In: Arch Neurol . 42 (4), 1985, pp. 362-363. PMID 3885921 .

- ^ AS Cohen, B. Burns, PJ Goadsby: High-flow oxygen for treatment of cluster headache: a randomized trial . In: JAMA . tape 302 , no. December 22 , 2009, p. 2451-2457 , doi : 10.1001 / jama.2009.1855 , PMID 19996400 .

- ↑ a b c A. May, M. Leone, J. Áfra, M. Linde, PS Sándor, S. Evers, PJ Goadsby: EFNS guidelines on the treatment of cluster headache and other trigeminal-autonomic cephalalgias. In: Eur J Neurol. 13, 10, Oct. 2006, pp. 1066-1077. doi: 10.1111 / j.1468-1331.2006.01566.x . PMID 16987158 . efns.org (PDF)

- ↑ J. Schoenen, RH Jensen, M. Lantéri-Minet, MJ Láinez, C. Gaul, AM Goodman, A. Caparso, A. May: Stimulation of the sphenopalatine ganglion (SPG) for cluster headache treatment. Pathway CH-1: a randomized, sham-controlled study . In: Cephalalgia . tape 33 , no. 10 , July 2013, p. 816-830 , doi : 10.1177 / 0333102412473667 , PMID 23314784 , PMC 3724276 (free full text).

- ↑ a b Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices: Evaluation of the off-label expert group in the field of neurology / psychiatry according to Section 35b (3) SGB V on the use of “Verapamil for the prophylaxis of cluster headaches.” July 16, 2012

- ↑ AS Cohen, MS Matharu, PJ Goadsby: Electrocardiogram Graphic abnormalities in patients with cluster headache on verapamil therapy. In: Neurology. 69 (7), 2007, pp. 668-675. PMID 17698788

- ↑ H. Goebel, H. Holzgreve, A. Heinze, G. Deuschl, C. Engel, K. Kuhn: Retarded verapamil for cluster headache prophylaxis. In: Cephalalgia. 19 (4), 1999, pp. 458-459.

- ^ DW Dodick, TD Rozen, PJ Goadsby, SD Silberstein: Cluster headache. In: Cephalalgia. 20 (6), 2000, pp. 787-803. PMID 11167909 .

- ^ The portal for drug information of the federal and state governments: pharmnet-bund.de February 6, 2011.

- ^ S. Schuh-Hofer, H. Israel, L. Neeb, U. Reuter, G. ArnoldS. Schuh-Hofer, H. Israel, L. Neeb, U. Reuter, G. Arnold: The use of gabapentin in chronic cluster headache patients refractory to first-line therapy. In: Eur J Neurol . tape 14 , no. 6 , June 2007, p. 694-696 , doi : 10.1111 / j.1468-1331.2007.01738.x , PMID 17539953 .

- ↑ M. Karst, JH Halpern, M. Bernateck, T. Passie: The non-hallucinogen 2-bromo-lysergic acid diethylamide as preventative treatment for cluster headache: an open, non-randomized case series . In: Cephalalgia . tape 30 , no. 9 , September 2010, p. 1140-1144 , doi : 10.1177 / 0333102410363490 , PMID 20713566 . - Comment in the DMKG headache news. 3/2009, pp. 59–60 (PDF; 498 kB) (PDF)

- ^ A. Ambrosini, M. Vandenheede, P. Rossi, F. Aloj, E. Sauli, F. Pierelli, J. Schoenen: Suboccipital injection with a mixture of rapid- and long-acting steroids in cluster headache: a double-blind placebo-controlled study. In: Pain. 118 (1-2), Nov 2005, pp. 92-96. Epub 2005 Oct 3. PMID 16202532 , doi: 10.1016 / j.pain.2005.07.015 , PAIN abstract + free full text . Comment in: Pain. 121 (3), Apr 2006, pp. 281-282. PMID 16513278 , doi: 10.1016 / j.pain.2006.01.005

- ↑ Felisati et al. a .: Sphenopalatine endoscopic ganglion block: a revision of a traditional technique for cluster headache. In: Laryngoscope. (2006) (abstract) PMID 16885751

- ↑ Donnet et al. a .: Trigeminal nerve radiosurgical treatment in intractable chronic cluster headache: unexpected high toxicity. In: Neurosurgery. 59 (6), 2006, pp. 1252-1257. PMID 17277687 .

- ↑ McClelland et al. a .: Long-term results of radiosurgery for refractory cluster headache. In: Neurosurgery. 59 (6), 2006, pp. 1258-1262. PMID 17277688

- ↑ McClelland et al. a .: Repeat trigeminal nerve radiosurgery for refractory cluster headache fails to provide long-term pain relief. In: Headache. 47 (2), 2007, pp. 298-300. PMID 17300376 .

- ↑ Burns et al. a .: Treatment of medically intractable cluster headache by occipital nerve stimulation: long-term follow-up of eight patients. In: The Lancet. 369 (9567), 2007, pp. 1099-1106. PMID 17398309

- ↑ Magis et al. a .: Occipital nerve stimulation for drug-resistant chronic cluster headache: a prospective pilot study. In: Lancet Neurology. 6 (4), 2007, pp. 314-321. PMID 17362835 .

- ↑ Leone et al. a .: Stimulation of occipital nerve for drug-resistant chronic cluster headache. In: Lancet Neurology. 6 (4), 2007, pp. 289-291. PMID 17362827 .

- ↑ M. Leone et al. a .: Hypothalamic stimulation for intractable cluster headache: long-term experience. In: Neurology. 67 (1), 2006, pp. 150-152. PMID 16832097 .

- ↑ S. Evers, P. Kropp, R. Pothmann, F. Heinen, F. Ebinger: Therapy of idiopathic headaches in children and adolescents - Revised recommendations of the German Migraine and Headache Society (DMKG) and the Society for Pediatric Neurology (GNP) . In: Neurology . tape December 27 , 2008, p. 1127-1137 . DMKG (PDF) schattauer.de ( Memento of the original from March 20, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Instructions for use Imigran® Nasal mite 10 mg, as of January 9, 2018, accessed on March 29, 2019 (PDF)

- ↑ Instructions for use AscoTop® nasal spray, December 2010

- ↑ Peter Batcheller: A Survey of Cluster Headache (CH) Sufferers Using Vitamin D3 as a CH Preventative. In: Neurology. 82 (Sup 10), 2014, p. P1.256.

- ^ RA Sewell: Response of Cluster Headache to Kudzu. In: Headache. 2009 Jan; 49 (1), pp. 98-105. PMID 19125878 doi: 10.1111 / j.1526-4610.2008.01268.x

- ^ RA Sewell, JH Halpern, HG Pope Jr: Response of cluster headache to psilocybin and LSD. (PDF; 245 kB) In: Neurology. 66 (12), 2006, pp. 1920-1922. PMID 16801660 .

- ↑ H. Göbel, HC Diener, KH Grotemeyer, V. Pfaffenrath: Therapy of cluster headaches . In: pain . tape 12 , no. 1 , February 1998, p. 39-52 , doi : 10.1007 / s004829800015 , PMID 12799991 .

- ↑ Peter J. Goadsby, David W. Dodick, Massimo Leone, Jennifer N. Bardos, Tina M. Oakes, Brian A. Millen, Chunmei Zhou, Sherie A. Dowsett, Sheena K. Aurora, Andrew H. Ahn, Jyun-Yan Yang, Robert R. Conley, James M. Martinez et al .: Trial of Galcanezumab in Prevention of Episodic Cluster Headache . In: New England Journal of Medicine . tape 381 , no. 2 , July 11, 2019, p. 132-141 , doi : 10.1056 / NEJMoa1813440 .

- ↑ H. Isler: A hidden dimension in headache work: applied history of medicine. In: Headache. 26 (1), 1986, pp. 27-29. PMID 3536800 .

- ^ PJ Koehler: Prevalence of headache in Tulp's Observationes Medicae (1641) with a description of cluster headache. In: Cephalalgia. 13 (5), 1993, pp. 318-320. PMID 8242723 .

- ^ HR Isler: Thomas Willis' two chapters on Headache of 1672: A First Attempt to Apply the "New Science" to this Topic. In: Headache. 26 (2), 1986, pp. 95-98. PMID 3514551 , doi : 10.1111 / j.1526-4610.1986.hed2602095.x .

- ^ HR Isler: Episodic cluster headache from a textbook of 1745: van Swieten's classic description. In: Cephalalgia. 13 (3), 1993, pp. 172-174. PMID 8358775

- ↑ MH Romberg: Textbook of human nervous diseases. Duncker. Berlin 1840-1846.

- ^ SH Ahamed, NS Jones: What is Sluder's neuralgia? In: Laryngology and Otology. 117 (6), 2003, pp. 437-443. PMID 12818050 .

- ↑ a b K. A. Ekbom: Ergotamine tartrate orally in Horton's 'Histaminic cephalgia' (also called Harris's 'ciliary neuralgia'). In: Acta Psychiatr Scand. 46, 1947, pp. 106-113.

- ^ HR Isler: Independent historical development of the concepts of cluster headache and trigeminal neuralgia. In: Functional neurology. 2 (2), 1987, pp. 141-148. PMID 3311902 .

- ↑ W. Harris: Neuritis and Neuralgia. Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford 1926.

- ↑ W. Harris: Ciliary (migrainous) neuralgia and its treatment. In: Br Med J. 1, 1936, pp. 457-460.

- ^ A b C. J. Boes, DJ Capobianco, MS Matharu, PJ Goadsby: Wilfred Harris' early description of cluster headache. In: Cephalalgia. 22, 2002, pp. 320-326. PMID 12100097

- ↑ Ottar Sjaastad: Cluster Headache Syndrome. WB Saunders, London 1992, ISBN 0-7020-1554-7 , pp. 6-18.

- ^ W. Harris: The facial neuralgias. Humphrey Milford, Oxford University Press, London 1937 - quoted from Boes (2002).

- ↑ HH Vail: Vidian neuralgia, with special reference to eye and orbital pain in suppuration of petrous apex. In: Ann Otolaryngol. 41, 1932, p. 837.

- ↑ DIMDI: International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10)

- ↑ A. May: The future of headaches . In: pain . tape 18 , no. 5 , October 2004, p. 349-350 , doi : 10.1007 / s00482-004-0365-8 , PMID 15449165 .

- ^ HG Markley, DC Buse: Cluster headache: myths and the evidence . In: Curr Pain Headache Rep . tape 10 , no. 2 , April 2006, p. 137-141 , doi : 10.1007 / s11916-006-0025-z , PMID 16539867 .

- ↑ BT Horton: Histaminic cephalgia. In: J Lancet. 72 (2), 1952, pp. 92-98. PMID 14908316 .

- ↑ BT Horton: Histaminic cephalgia: differential diagnosis and treatment. In: Bull Tufts N Engl Med Cent. 1 (3), 1955, pp. 143-156. PMID 13284539 .

- ↑ DJ Capobianco, JW Swanson, BT Horton: Neurologic contributions of Bayard T. Horton. In: Mayo Clin Proc . tape 73 , no. 9 , September 1998, pp. 912-915 , doi : 10.4065 / 73.9.912 , PMID 9737233 ( mayoclinicproceedings.org ).

- ↑ BT Horton, AR MacLean, W. Craig: A New Syndrome of Vascular Headache: Results of Treatment with Histamine. In: Proc Staff Meet, Mayo Clinic. 14, 1939, p. 257.

- ↑ EC Kunkle u. a .: Recurrent letter headache in cluster pattern. In: Trans Am Neurol Assoc. 56 (77), 1952, pp. 240-243. PMID 13038844 .

- ^ Ad Hoc Committee on Classification of Headache: Classification of Headache. In: JAMA. 179, 1962, pp. 717-718.

|

Note: This article is based in part on GFDL- licensed texts that were taken from the CK-Wissen-Wiki . A list of the original authors can be found on the version pages of the CK-Wissen articles History of Cluster Headache , Symptoms , Symptomatic Cluster Headache , Diagnosis , Causes , Treatment , Triggers , Occipital Nerve Stimulation, and Deep Brain Stimulation . |