Dietkirchen (Bonn)

The name Dietkirchen Bonn stands for several terms that have played an important role in the history of today's federal city of Bonn and its region. Dietkirche (= Volkskirche) was not only the name of a first Christian church , but also the origin of the name of an early settlement that had developed around the church. Dietkirchen also became the name of the later parish (Sprengel) and also the name of a monastery founded by the church, from which the free aristocratic St. Petrus monastery in Dietkirchen later emerged. Dietkirchen Monastery was one of the first religious-female convents in the Bonn area , along with the founding monasteries in Vilich (978) and Schwarzrheindorf (1151). Dietkirchen Abbey was abolished under French administration in 1802 and its property was confiscated.

history

Roman-Frankish period

In the post-Roman period, the oppidum castrum Bonna - at the south-west corner of the former Roman camp - was transformed into a mixed ubic-Roman settlement. In this - since the turning away from the pagan faith - a Christian community had formed in Frankish times , which saw itself as a people's church (= Diet Church). In contrast to other churches that emerged early, the Dietkirche was initially the only parish church with the right to baptize and is regarded as the original parish of the Bonn area.

Exposure of the original church in Bonn's northern part

However, there are no documents relating to the early history. A replacement owed to today's science are the archaeological findings that were discovered in the 1970s in the area around the former Dietkirche through the excavation campaign "Loëkaserne" (Rheindorfer Str., Later BMF ) with the remains of the foundation wall uncovered there.

The tangible traces of a church from the 6th century found in the ground of the green area of a new housing estate (Graurheindorfer Straße / Am Römerkastell / Drususstraße) are ascribed to a very early Christian community in the region. The exact year in which the exposed foundations of the church buildings are to be classified remains unanswered. The small, rectangular stone church, which was built in the late Roman period, at the latest in the early Franconian period, whose first successor left the remains of a semicircular apse , was the core of a growing settlement until it was ruined.

This was built between 1002/21 as the Church of St. Petrus in Thiedenkireca, whose nuns of the local monastery Emperor Heinrich II gave his chamber property to Bibern (Engers, today Neuwied) and which later, on August 10, 1021, as “de monasterio sancti Petri Thietkircha dicto in suborbio Bvnae sito, ad altare predicti Sancti Petri apostuli ”. At that time Abbess Bertswindis was in charge of the convent, and in the donation she was named “abatissa [e] de monasterio s. Petri Thietkiricha dicto in suburbio Bvnnae sito ”.

chronology

Early middle ages

In 795 (but probably earlier) a Christian church is said to have stood near the ruined Roman castrum , which was documented as a "church equipped with its own property".

With Gunthar , who served as the first archbishop of the Archdiocese of Cologne from 850 to 863, massive upheavals began in the history of the church so far. In 866 Archbishop Gunthar recognized the development of individual churches to become independent, so that monasteries and monasteries could also award or accept endowments from churches. After that, most of Bonn's churches were and became fiefs , which were given by the provost of Bonn's Cassius Foundation. Only St. Remigius in Bonn, which was initially a separate church of the archbishop in Cologne, and the Dietkirche in the foreland had a different status. Dietkirchen later went to the Benedictine monastery founded before 1015 and later the free aristocratic women's monastery of St. Petrus in Dietkirchen.

Turn of the millennium

A wealthy Benedictine monastery is said to have been founded in Dietkirchen near the church of the same name between 1000 and 1015. The builder and first abbess was Mathilde, daughter of Ezzo, Count Palatine of Lorraine . She was also abbess in Dietkirchen and Vilich. There she was the successor to Abbess Adelheid , whose parents Megingoz von Geldern and Gerberga had founded a Benedictine monastery. The number of conventuals or canons is said to have been twelve until modern times, although the full number of documents was rarely reached. It is said of the "maidens" (Stiftsfräulein) that they belonged to the lower nobility, whose families were resident in the Bonn area.

The head of a sandstone relief dated around 1015 is said to have been part of the facade of the early Gothic Dietkirche. It was also mentioned in a document from 1015 - it is the oldest in the church history of the city of Bonn today - which for the first time documents a women's convent near the Dietkirche, which was founded only a few years earlier as a monastery of the Benedictine nuns. Among other things, the certificate states:

"Cuidam monasterio Bunne constructo, in honore Sancti Petri apostolorum principis dicato"

These and other documents attest to the beginnings of the later women's monastery .

High and late Middle Ages

The decline in discipline of the order in Dietkirchen led to a monastery reform ordered by Archbishop Rainald von Dassel in 1166 , in which he once again placed the association, which was first designated as a women's convent in a document from 1015, under the rule of St. Benedict - a status that was officially retained until it was converted into a monastery, even if the strict regulations were liberalized over the decades. Reinald also forbade the alienation of the previously pledged goods that had been reacquired by Abbess Ermentrude. In 1246 Archbishop Konrad allowed in his diocese to carry out collections for the renovation or reconstruction (reedificare) of the Dietkirche, which was threatened with collapse.

A baptismal font made of basaltic lava dated to around 1290 was found and reconstructed in its bricked-up fragments in the demolition material of the later Baroque church. This, and the so-called Dietkirchenmadonna from the 14th century are traditional treasures. They adorn today's Gothic-style church, designed by Heinrich Wiethase . It is currently not known when the baptismal font, which at times also served as a “people's altar ”, and the sculpture of the Madonna and Child came into the possession of the parish church; however, they will have come to the Dietkirche later, as it was dependent on donations for a new building (which was under construction around 1316/17) at the end of the 13th century (appeal for donations by Archbishop Sifrid ) and also in the beginning of the 14th century was. A later passage from an entry from 1647 also shows that the interior of the church was poorly furnished. Even the buildings of the convent were not spared from damage in the city, which is often hit by warlike gangs. A document from 1320 reports that the abbess Ponzetta zu Dietkirchen - sister of Archbishop Heinrich II. Von Virneburg - had to rebuild a dormitory in Dietkirchen that had been destroyed by fire / arson before 1320 for around 1000 marks . According to the Cologne archbishop's registers, a crypt of the church is said to have existed in 1317, which was described as the oldest part of the building.

A transfix of 1327 said that in December 1326 Dominicus Patriarch of Grado (1318-1332) and eleven bishops in Avignon for devotional visits to the parish church of St. Peter in Dietkirchen on certain days as well as for contributions to the building budget, lighting, ornamentation or other Granted a 40 day indulgence based on Church requirements. The granting of the 40-day indulgence right seems to have been successful, because only three years later, in 1330, an entry said: Manufacture of the monastery buildings. A house on the market adjacent to the monastery was also mentioned for this year.

Possessions of the pen

The possessions were of various kinds and were initially based on foundations or bequests. With the increasing prosperity of the convention, acquisitions also took place. In addition to the privileges received, such as fiefs, tithe, market rights and interest income, capital was built up through construction in villages and towns in the surrounding area. Another example was real estate. The "big cities" Bonn and Cologne owned a city courtyard, residential buildings and commercial facilities such as breweries and mills (e.g. the Steinbrück monastery mill, which belonged to the Mülheim area). The spots Mülheim was demolished as part of the expansion of existing fortifications before the "Mülheim dürlein", where not only the pin mill, also called "junffern Moelen zo Dietkirchen" called, but also 146 acre fields and vineyards were lost. After the mill was destroyed, Dietkirchen was part of the Dransdorfer Mühlenzwang . Furthermore, there was intensive wine-growing and processing (wine press houses), the income of which contributed significantly to prosperity. In the then still sparsely populated areas, forestry (oak wood) was one of the first branches of business to generate profits in the form of the coveted wood material, but also after the clearing of forest areas by the Rottzehnten (see Urfeld). Another line of business was sheep and fish farming, which Dietkirchen operated in Walberberg (yard Krawinkel) and Sechtem (Stiftshof). In addition to these variants, there were mostly ten-duty manors with their lands, which were often (but not only) located in the foothills region and were managed by Halfen . These included the already mentioned Königswinter, Dottendorf, Friesdorf and Gielsdorf .

Since a donation in Winetre in 1050, however, these have mainly been in the north of Bonn. This included property in Urfeld , Sechtem , Walberberg (in 1163 the Stiftshof Krawinkel was named among the estates of the Dietkirchen Abbey), Waldorf , Widdig , Roisdorf and Buschhoven .

Further lands and farms were in Liblar and Spurk , in Köttingen the Wedemhof and four other farms, one farm in Blessem , two farms in Roggendorf, today Kierdorf (Erftstadt) (1113 named as "Rouchesdorp" in a document from the Dietkirchen monastery), farms in Brüggen and the Stiftsmühle in Brüggen belonged to the property, as well as larger forest parcels in Türnich and Köttingen, which were referred to as "fiefs". The owners of the farms and forest parcels were obliged to take part in the Kurmede. They appeared as court jury members at the court court on the Fronhof, where, under the chairmanship of the collegiate waiter, due taxes, re-allocation of farms, health cures and divisions of inheritance were negotiated. The monastery had tithe rights in the parish of Liblar (Liblar, Spurk and Köttingen) and forest rights. In addition to the extensive possessions taken over by the Benedictine nuns, the canons of the Dietkirchen canonical monastery increased their possessions. Gradually they owned properties on both sides of the Rhine.

Separation of property and community of monasteries

In order to better secure the livelihood of the conventual women, Archbishop Walram carried out a separation of property between the abbess and the convent in 1341. The reason for the measure, which Walram ordered for the material sharing of property and income between the convent and the monastery management, is said to have been the enormous increase in debts of the monastery under the abbess Sofia at that time.

He awarded the abbess the monastery courtyards in Urfeld, Eichholz and Widdig, except for the larger one of the barns in Eichholz. This fell to the convent, which relocated it to Sechtem in order to use it there as a tithe barn . The monastery courtyards in Antweiler, Satzfey, Buschhoven, Liblar and Krawinkel were allowed to be leased by the abbess, but her income was now split. The abbess received a share of 2/5, the convent 3/5. Furthermore, the abbess retained the rule over the vassals, feudal men, wax interest and fiefdoms with jurisdiction , Kurmeden and income, with the exception of the Kurmeden of the Waldorf and Roisdorf farms.

As with other monasteries, abbeys , the possessions of the nobility or external properties of the cities and rural communities, Dietkirchen marked its lands and forests in the Feldmark with ban / boundary stones. Such a stone was found on the so-called “Donnerstein” in the corridor of the Dietkirchener Hof in the Bornheim district of today's Roisdorf district. It bore the letters "SSP IN D K" = St. Petrus Monastery in Dietkirchen.

The abbess received the monastery fishery in the Rhine near Urfeld, two wood forces in Morenhofen and three acres of meadows. The stipend , which they had in Dietkirchen they had received from their farms. She received her share of the daily attendance fees when she was in Dietkirchen. Also the Äbtissinnenhaus in Dietkirchen remained the respective Head, except two wine house, a wine cellar and the upper chamber of the Convention, however, was reserved for the abbess of the part. She was also allowed to build a horse stable at the monastery gate in Dietkirchen, to which the convent had to contribute. The abbess kept the monastery regiment to the same extent as her predecessors, but she was excluded from the administration of the property. From then on, this was a matter for the convent and possibly employed canons.

Various monasteries behind the monastery wall

Reports on a gate building (portzen huys), a kitchen and a piste (bakery) etc. come from the years 1425/39. Several invoices from this period also mention a tower that had four bells ringing and, since 1438, a horologion . A Pütz (fountain) mentioned in 1427, which is said to have stood in the Pesch (garden of the cloister) and may have been the post-Roman St. John's fountain, which was rediscovered in 1880 under the southern part of the former barracks, also falls during this period.

Johannismarkt Dietkirchen

A "forum" (market) in front of Dietkirchen was mentioned as early as 1150, and a "Heidericus de Foro" was mentioned by name. On July 2, 1349, Emperor Charles IV confirmed the market village of Dietkirchen a previously received privilege, according to which a market in Dietkirchen could be held every year. The church and the monastery building were close by and the market area was directly on the Kölner Landstrasse , not far from the Kölner Tor in a corridor backed by vineyards. According to Merian's drawing from 1642, the market area had two cattle troughs and the center of the square was adorned with a high stone market cross, named Johanniskreuz after the patronage of the church and convent. The time of the fair to be held was also fixed. It began every year for the vigil of the patron saint John the Baptist on June 23rd and lasted until the feast day of Saints Peter and Paul on June 29th. From time immemorial, the chapter or the convent (not the abbess) exercised its right to the tax-free tapping of wine during the market by letting the servants sell their own wines. The fair - and also its St. John's Cross - were only moved to Münsterplatz during the French period . The cross has been in Bonn's old cemetery since around 1850 . The street "Am Johanneskreuz", which runs between Rosental and Kölnstrasse , is also reminiscent of the Dietkirchener Kreuz . The market was on a country road that had traditionally served as a trade route. They were called in 1393 “up der Collerstrayssen”, 1516 “up der Collerstrayss” and in the Buschhoven area “up der bunnerstraiss”, 1603 “on the high, long, the Colnish straiss” or “the ordinary of Colln go Mentz (Mainz) going free kayserliche Country roads ". In 1658 it was the "Cölnische Landstraßen", which in 1738 was called the Heerstraße between Bonn and Cologne.

Tyeten Kirchhove burial place

On the land mentioned in 1369 “on Tyeten Kirchhove up dem Crüytzvelde”, the first of the two cemeteries of the convent may have been laid out. It was a divided area, with one half intended for the final resting place of the conventual women - Abbess Ponzetta was buried in the Barbarakapelle of the cathedral church - and the remaining part was the burial place of the parishioners.

Transitional period to the monastery constitution

The early onset of neglect of the monastic rules, which began and continued in the 12th century, found both imitators and critics. In 1230 and 1240 the monk and chronicler Caesarius von Heisterbach lamented the abuses in the monasteries in the region. However, over the years, these rules were handled more and more liberally and were de facto abandoned in the 14th century with the deed of partition of 1341. Dietkirchen was formally a monastery, but it functioned as a monastery whose canons (canonice religionis) had their own income. Before the end of the 15th century, permission to use the more liberal monastery constitution had been given, but it was not until 1483 that Pope Sixtus IV converted the Dietkirchen monastery into a free secular women's monastery, in which the canonies were permitted without vows , habit or enclosure to live under an abbess. The years 1485 to 1492 are the years of office of the plebanus Petrus Becker, who became a pastor in Dietkirchen after studying theology at the University of Cologne . Since there is evidence of a Petrus Michaelis from Bonn between 1485 and 1489, it is assumed that he may be identical to the deceased whose grave slab was found at the site of the medieval church. He had enrolled at Cologne University in 1478 and was ordained a priest in 1485.

Monastery and Church in Modern Times

Various documents (mostly feudal contracts), the contents of which were indirectly related to the monastery, showed that Mettel von Hanxleben was the abbess of the monastery in 1506/1509 . Margarethe Wolff is documented for the year 1552.

In 1583 (100 years after the conversion to the monastery) the documents mention a dormitory, which according to the Benedictine rule was called Dormiters , as well as a price chamber (?) Of the church were mentioned. In the same year, an entry in the file reports “Church and monastery in Dietkirchen plundered and partially destroyed”. In 1615 the damage seems to have been repaired, because it says “according to the statutes, the service was held again in full”.

Altars and Canonicals

According to the statutes, according to the order of worship from 1330, but varying in number until 1615, there were between nine and 12 altars , which were assigned to various canons . They were the St. Peter altar (1021 main altar, 1615 high altar), 1241 and 1290 altar St. Johann Baptist (in the crypt) and in 1615 it is called Vic. S. Johannis , 1330 and 1576 St. Andreas in the crypt . 1615 it is called Vicarius of Andrew and the cross altar. In 1427 the altars are named S. Antonii and St. Benedictus . The latter is said to have been incorporated into the BMV altar in 1615. A St. Cassius altar was mentioned for 1330 , at which the provisional prebende animarum ( priest of soul mass ) celebrated. Also in 1330, Daniel von Elkerode (possibly in connection with Elkenroth ) donated an altar of the Dietkirchen crypt, which was consecrated to S. Catharina, and went to a vicarie in 1615. In 1370 there was the altar of Our Lady in the maiden choir . He earned his living by renting a house on the Johannismarkt and in 1371 by renting a house on the Wenster (l) pforte between the Kölner Pforte and the new tower. A document from the parish archives of the collegiate church mentions the "Altar St. Michaelis monasterii in Dytkirck" for the year 1290 - the time from which the preserved baptismal font originates . The list is followed by the altar of St. Nikolaus (1615), St. Stephan (1330, 1615 united with two others), St. Trinity (1330, 1615 united with two others) and the altar of St. Welricus in the Balderich Chapel.

Due to the imminent danger of imminent attacks on Bonn, the military of the garrison there took various precautions to counter this threat and converted the Dietkirchen apron into a fortress glacis. Since the destruction of the monastery in the foothills and its church in 1673 probably proceeded according to plan, valuable items of equipment were probably brought to safety or sold in good time.

Merian's city view

A short note on the Dietkirchen monastery church reported on the years 1646/47. It was called "The church, which is small and poorly equipped ..." and in 1653 a renovation seems to have come to an end, because it says: "nunc anno 1653 renovatum". Clemen says about the Dietkirche: "According to Merian's illustration, the church was an early Gothic building, the exterior of which corresponded to the style of the Minorite Church described by R. Pick". About two decades after the Swiss engraver Matthäus Merian also made his sketches in the Rhineland, the plague epidemic had also reached the Cologne-Bonn area and destroyed many human lives. As the epidemic mainly found its victims in the cities, the wealthy fled to rural refuges . The abbess from Bonn fled to their properties on the edge of the foothills with her canonesses, with the young ladies staying at the Sechtemer Ophof and the abbess at Gut Eichholz (her summer residence). From 1605 to 1620 Beatrix von Honeppel (called von Impel) was in charge of the affairs of the monastery. In 1654 and 1655 as well as in 1663 Anna Maria von Velbrück is abbess of Dietkirchen Abbey. In a contract of 1662/63 - since the separation of property between the abbess and the convent in 1341, the nuns were legally competent in their own affairs even without an abbess - a number of the canonesses are named by name. Fraulein Maria von Velbrück zu Horst, Sophia Agnes von Kolff zu Haußen, Maria Francisca Elisabetha von Steinen, Anthonetta von Hersel zu Bodenheim and other nuns signed a modified 12-year lease agreement with the half of the Sechtemer Ophofe on behalf of the convent. Paragraph four of the contract stated: "The tenants deliver 134 Malter grains (1 Malter = 143.54 liters) in various sorts to the Dietkirchener Speicher in Bonn or Cologne every year at Martini and two weeks later." Preparatory measures began as early as 1669 at the level of the Cologne Gate to set up a fortress pale in front of the city wall . Among other things, ½ acre of the Teutonic Order's vineyard in Cologne was drafted there.

In 1672 work began on the Kölntor itself, and the "fortification" there lasted until October 1673. In this context, due to the impending Dutch War and the siege of Bonn , the monastery buildings in front of the city walls and the Dietkirche are said to have been laid down for defense reasons. In the records of the parish archives it says: "Destruction of the monastery, the house of the abbess, the fräulein house, the granary, the brewery and bakery".

Church and monastery within the city walls

After about 13 years, the canons, who had fled to the countryside from the plague, returned to Bonn and temporarily lived in the house of a Bonn cleric, which was located on Kleinhöfchen (today's Martinsplatz). In 1680, they were given permanent abode in the house of Canon Piesers near the Kölner Tor in Paulsgasse or Baggertsgasse. In 1290 it was first called “de domo et area in vicho sancti Pauli” and around 1393 “up der Pauwelsgassen oerde”. There lived one of the few houses in Gasse Begarden that had lived in Bonn since the 14th century. They devoted themselves to nursing (Hospital Overstolz) and used the St. Paul chapel there for prayer. After the elector Max Heinrich had transferred the Overstolz court there, "which was otherwise ordained to a hospital or plague hospital" and the St. Paul chapel, the canonesses tried to redesign their future and the future of the monastery. A wine press and storage house was soon built there again. Here in Paulsgasse Maria von Velbrück is recorded as abbess for 1681, who was replaced by Odilia von Wylich in 1715 at the latest .

Succession to the St. Paul Chapel

Foundations for the construction of the baroque church

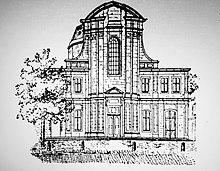

The temporal deterioration of St. Paul's Chapel (Merian's drawing) and the growing number of parishioners at the beginning of the 18th century required a new church to be built in the former Paulsgasse. It was renamed Baggertsgasse after 1531 and was later given the current name Stiftsgasse (in 1736 in the street directory).

In 1725 the elector Clemens August donated 160 Reichstaler for the building of the church, which were to be paid annually for the time being. In May 1729, a contract was signed with the architect and builder Maevis Bongarts to carry out the construction (contract text in the Düsseldorf State Archives). The designed building was a cross-shaped church in the contemporary Baroque style, the central dome of which reached a height of about 22 meters. Clemens August laid the foundation stone in person in July 1729.

This subsequently also donated 4,000 Reichstaler for a special “facciata” facade design. In 1730 Dietkirchen was forced to take out a loan of 5000 Reichstaler to continue building the church. In 1737, Countess von Polheim donated 1000 guilders (Oberland) to make a high altar, and H. von Gymnich contributed 250 Reichstaler for the same purpose. A collection for the construction work on the church yielded a further 7,109 Reichstaler 66 Albus .

The years before the abolition

In 1742 Theresia Philippa von Gymnich assumed the office of abbess. In 1773, the city map mentions a fountain on Kölnstrasse / Stiftsgasse (a Pütz at this point was mentioned as early as 1591 and 1699; it may be the forerunner of today's fountain on Stiftsplatz opposite the collegiate church). In the same year it was said about the monastery: “The St. Petri monastery in Dietkirchen, on the left, the iron grating where you go to the church, next to the grating pomp (pump), 3 altars (in the chapel), in front of the street the house where the abbess lives ”.

Last abbess

In the information on the history of the monuments in the Bonn district, the historian Paul Clemen mentions that there was a bell cast by Petrus Legros (son of Martin Legros ) in the parish church of Sechtems with the following inscription:

"S. ANNA BEY YOUR DAUGHTER'S CHILD ASK FOR THOSE YOUR SERVANTS ARE.

M. ANNA LB DF BOURSCHEID, ABBATISSA IN DIETKIRCHEN.

PETRUS LEGROS FECIT ANNO 1785 "

The "Abatissa" LB de Bourscheid named in the bell inscription seems to have been the last abbess of the monastery known by name. For the year 1790 the files record the status of the members of the monastery: abbess, 9 young ladies and a clergyman as secretary.

Dietkirche's last churchyard

The first so-called St. Pauli Kirchhof in 1721 is reported to have been used by the monastery since 1774 to bury its deceased. According to today's knowledge, it was not too far away from the location of today's collegiate church, whose address is Kölnstrasse 31. Dietz reports that skeletons were found in the floor of the rear part of the house at Kölnstrasse 45 after the Second World War , which would have come from the St. Paulus churchyard.

Lifting of the pen

The medieval history associated with the name Dietkirchen also ended under French administration. The church system now had to be based on the regulations of the mother country of the French, which had to apply the Concordat concluded in 1801 between Napoleon and Pope Pius VII, including the attached Napoleonic articles , in the area on the left bank of the Rhine .

In 1802, monasteries and monasteries were abolished, spiritual property confiscated and nationalized, and many a church was profaned. The previous parish of Dietkirchen was expanded to include parts of the Gangolf parish . The name collegiate church, which has been used since ancient times, has only been used for the church of St. Johann Baptist and Petrus in northern Bonn, but not for the Bonn Minster. The name Dietkirchen lost its meaning and disappeared except for the street name Dietkirchenstraße between Kölnstraße and Nordstraße, which had existed since 1910 .

literature

- Irmingard Achter, Die Stiftskirche St. Peter in Vilich , in: Die Kunstdenkmäler des Rheinlandes , Rudolf Wesenberg (Ed.), Rheinland Verlag Düsseldorf 1968

- Irmingard Achter, Bonn churches and chapels. History and art of Catholic churches and parishes , Wilhelm Passavanti (ed.). F. Dümmler Verlag Bonn, 1989 ISBN 3-427-85031-5

- Karl Friedrich Brosche, The history of the women's monastery and later canonical monastery Dietkirchen near Bonn from the beginnings of the church to 1550, diss. Phil. mach. Bonn 1951.

- Hermann Cardauns , Regesta of the Archbishop of Cologne Konrad von Hochstaden (1210) 1238–61 in Historical Association for the Lower Rhine: - Annals of the Historical Association for the Lower Rhine, in particular the old Archdiocese of Cologne, issue 35–37. - Cologne / Printing M. DuMont-Schauberg'sche Buchhandlung, 1880–82

- Paul Clemen , on behalf of the Provincial Association of the Rhine Province Die Kunstdenkmäler der Rheinprovinz, in: Die Kunstdenkmäler der Stadt und der Landkreis Bonn , Volume V, III. Druck und Verlag L. Schwann, Düsseldorf 1905, reprint 1981. ISBN 3-590-32113-X

- Josef Dietz, topography of the city of Bonn from the Middle Ages to the end of the electoral era , in Bonn history sheets. Yearbook of the Bonner Heimat- und Geschichtsverein, Volume XVI, 1962

- Karl Gutzmer , Chronicle of the City of Bonn . Publisher: Chronik Verlag (1988) ISBN 3-611-00032-9 Yearbook of the Cologne History Association, Volume 20, Verlag Creutzer & Co. Cologne 1938

- Richard Knipping (arr.), The Regests of the Archbishops of Cologne in the Middle Ages. Third volume first half 1205-1261 Bonn 1909 No. 1254 p. 181

- Gisbert Knopp , in Bonn churches and chapels . Wilhelm Passavanti (Ed.) History and art of the Catholic parishes and places of worship. F. Dümmler Verlag Bonn, 1989 ISBN 3-427-85031-5

- German Hubert Christian Maaßen , History of the Parishes of the Dean's Office Bonn, Part 1: City of Bonn (1894)

- Wolfgang Peters, The Founding of the Benedictine Monastery of St. Mauritius . Yearbook of the Cologne History Association 54, 1983

- R. Pick, History of the Collegiate Church in Bonn, Bonn 1884

- Renaissance am Rhein, catalog for the exhibition in the LVR-Landesmuseum Bonn, 2010/2011. Published by Hatje Cantz. ISBN 978-3-7757-2707-5

- Georg Schwedt, Bonn am Rhein in the mirror of the engraver Merian, journeys into the history of the city . Verlag BoD, Norderstedt, ISBN 978-3-7412-3813-0

- Heinz Vorzepf, Sechtem village chronicle ,

- Volume 2: Church and School through the Ages. 2001.

- Volume 3: History of our homeland, castles and farms. 2008.

- Norbert Zerlett, Landmarks in Field and Forest. In: Brühler Heimatblätter. No. 2/1978, p. 35.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Paul Clemen : The art monuments of the Rhine province . Volume 5: The art monuments of the city and the district of Bonn. 1905, introduction to the volume.

- ↑ Norbert Schloßmacher, "Bonner Kirchen und Kapellen", section Parish St. Martin, p. 30

- ↑ Hugo Borger , Comments on the emergence of the city of Bonn in the Middle Ages, In: "From history and folklore of the city and area of Bonn", Festschrift J. Dietz, Publication of the Bonner Stadtarchiv 10 (Bonn 1973) 10-42

- ↑ Ulrike Müssemeier in: The Merovingian finds from the city of Bonn and its surrounding area, Bonn 2004, " Sölter excavation between 1971 and 1976"

- ↑ Documents on Heinrich II. Retrieved on April 16, 2018 .

- ↑ Josef Dietz in: Topography of the City of Bonn from the Middle Ages to the End of the Electoral Period , p. 125 (Diet, Stiftskirche Bonn, Pfarrarchiv U 1; MGDH II, no. 446)

- ^ Paul Clemen: The art monuments of the Rhine province . Volume 5: The art monuments of the city and the district of Bonn. 1905, p. 110.

- ↑ a b c d e Norbert Schloßmacher> in: Parish of St. Johann Baptist and Petrus, in Bonn churches and chapels . P. 17f

- ↑ Eduard Hegel, Dependence of Parish Churches on Church Lords, in “Bonn Churches and Chapels”. P. 3 f

- ↑ Irmingard Achter, Bonn churches and chapels. History and art of Catholic churches and parishes , p. 215ff

- ^ Heinz Vorzepf: History of the Sechtem parish church . Section Church Conditions (= Sechtemer Dorfchronik . Volume 2 ). Bornheim 2016, p. 23 .

- ^ Object information from the Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn

- ↑ Josef Dietz in: Topography of the City of Bonn from the Middle Ages to the End of the Electoral Period , p. 125 (Diet, Stiftskirche Bonn, Pfarrarchiv U1; MGDH II, No. 333)

- ^ Richard Knipping (arr.): The Regests of the Archbishops of Cologne in the Middle Ages. II. Volume. Bonn 1901. No. 863, pp. 151-152.

- ^ Josef Dietz in: Topography of the City of Bonn from the Middle Ages to the End of the Electoral Period , p. 125, Diet U 15

- ^ A b c Paul Clemen: The art monuments of the Rhine province . Volume 5: The art monuments of the city and the district of Bonn. 1905, introduction to the volume.

- ^ Gisbert Knopp, in Bonner Kirchen und Kapellen , p. 19 f

- ^ Regesta of the Cologne EB. IV, 1162

- ^ Josef Dietz in: Topography of the City of Bonn from the Middle Ages to the End of the Electoral Period , p. 125, Reg. Eb. Cologne, IV, 984

- ↑ Return note of the IV parish archives of St. Petrus, Bonn: Domino Hermanno plebano ... and registration note: No. 14 literae apostolicae super quadrangarum dierum indulgenciis cum transfixo sub sigilla Henrici archiepiscopi Coloniensis, qui addit in consimili forma quadraginta diesbris de indulgenciarum 22nd - 266th With transfix from 1327

- ^ Josef Dietz in: Topography of the City of Bonn from the Middle Ages to the end of the electoral era . P. 124 (Diet. U 30)

- ↑ Josef Dietz in: Topography of the City of Bonn from the Middle Ages to the End of the Electoral Period , p. 96 (Diet. U 37),

- ^ Karl Gutzmer, Chronicle of the City of Bonn, p. 49

- ^ Josef Dietz in: Topography of the City of Bonn from the Middle Ages to the End of the Electoral Period , several documents p. 215, Kurköln, Amt Bonn. Cologne R. 1681

- ^ Karl and Hanna Stommel (arr.): Sources on the history of the city of Erftstadt. Volume V. Erftstadt 1998, No. 2924 p. 280

- ↑ Josef Dietz in: Topography of the City of Bonn from the Middle Ages to the End of the Electoral Period , p. 124, (Diet. U 41)

- ↑ Norbert Zerlett: Boundary stones in the field and forest. Boundary stone 5.

- ^ Wilhelm Janssen (arr.): The Regests of the Archbishops of Cologne in the Middle Ages. VIII. Volume. Bonn 1973, pp. 218-219 No. 797

- ↑ Josef Dietz in: Topography of the City of Bonn from the Middle Ages to the End of the Electoral Period , p. 124, with reference to Maaßen (Diet A 14)

- ↑ Josef Dietz in: Topography of the City of Bonn from the Middle Ages to the End of the Electoral Period , p. 125, with reference to J. Dietz, Kulturbild des Kloster Dietkirchen from the 15th century , Bonner Geschichtsverein 37

- ↑ Josef Dietz in: Topography of the City of Bonn from the Middle Ages to the End of the Electoral Period , p. 125, with reference to R. Pick, Geschichte der Stiftskirche, 23, 34

- ↑ Josef Dietz in: Topography of the City of Bonn from the Middle Ages to the End of the Electoral Period , p. 96 (Diet A 17a, 5)

- ^ Josef Dietz in: Topography of the City of Bonn from the Middle Ages to the End of the Electoral Period , p. 96, B. Gesch. V 74.

- ↑ Georg Schwedt, Bonn am Rhein in the mirror of the engraver Merian, section Dietkirche and the Johanniskreuz, p. 48

- ^ Josef Dietz in: Topography of the City of Bonn from the Middle Ages to the End of the Electoral Period , p. 92, Düss. Kurköln, Bonn Office, Postal Services 2

- ^ Josef Dietz in: Topography of the City of Bonn from the Middle Ages to the End of the Electoral Period , p. 160, B. Gesch. V 38, Diet A, 6, 5f, Hei 403

- ↑ Irmingard Achter, The Collegiate Church of St. Peter in Vilich , p. 23

- ^ Heinz Vorzepf: History of the Sechtem parish church . Section Church Conditions (= Sechtemer Dorfchronik . Volume 2 ). Bornheim 2016, p. 9 .

- ↑ reference to; Hermann Keussen, Mat. 1, No. 358, 133

- ↑ Reference to: L. Schmitz, Die Priesterweihen Kölner Kleriker an der Kurie in the 15th and 16th centuries, AHVN 69, 1900, pp. 91–114 (105 no. 181).

- ^ Karl and Hanna Stommel (arr.): Sources on the history of the city of Erftstadt. III. Tape. Erftstadt 1993, No. 1458, No. 1459, No. 1460, No. 1787, pp. 49-50 and p. 195

- ^ Josef Dietz in: Topography of the City of Bonn from the Middle Ages to the End of the Electoral Period , p. 124, Diet A 4, 144

- ↑ Josef Dietz in: Topography of the City of Bonn from the Middle Ages to the End of the Electoral Period , p. 127, Diet A 4, 143 ff

- ↑ Josef Dietz in: Topography of the City of Bonn from the Middle Ages to the End of the Electoral Period , p. 127, with reference to Maaßen 229

- ↑ Augustinian choir women of the Congregatio Beatae Mariae Virginis

- ↑ Josef Dietz in: Topography of the City of Bonn from the Middle Ages to the End of the Electoral Period , p. 127, Stiftskirche Pf. AU 2a

- ↑ Josef Dietz in: Topography of the City of Bonn from the Middle Ages to the End of the Electoral Period , p. 127

- ^ Josef Dietz in: Topography of the City of Bonn from the Middle Ages to the End of the Electoral Period , p. 127, Yearbook of the Kölner Geschichtsverein 20 (1938) 152

- ^ Heinz Vorzepf: Burgen und Höfe, section Ophof (= Sechtemer village chronicle . Volume 3 ). Bornheim 2016, p. 350 .

- ^ Karl and Hanna Stommel (arr.): Sources on the history of the city of Erftstadt. IV. Volume. Erftstadt 1996. No. 2202, No. 2203, No. 204, No. 2275, p. 146 and p. 174

- ^ Karl Stommel: Johann Adolf Freiherr Wolff called Metternich zur Gracht. From country knight to country steward. A career in the 17th century. Cologne 1986, p. 303 and p. 342

- ^ Heinz Vorzepf: Burgen und Höfe, section Ophof (= Sechtemer village chronicle . Volume 3 ). Bornheim 2016, p. 347 .

- ↑ Josef Dietz in: Topography of the city of Bonn from the Middle Ages to the end of the electoral era , p. 27 f, reference to Cologne St- A Do A

- ↑ Josef Dietz in: Topography of the City of Bonn from the Middle Ages to the End of the Electoral Period , p. 27 f, Diet A 4.152 bf

- ^ Eduard Hegel, Dependence of the parish churches on church lords , in Bonn churches and chapels . P. 3 f

- ↑ Josef Dietz in: Topography of the City of Bonn from the Middle Ages to the End of the Electoral Period , p. 124, (Diet A IV, 153 b)

- ^ Josef Dietz in: Topography of the City of Bonn from the Middle Ages to the End of the Electoral Period , p. 61

- ^ Josef Dietz in: Topography of the City of Bonn from the Middle Ages to the End of the Electoral Period , p. 65, (Pf. A. Stift U 2 D 21

- ↑ Josef Dietz in: Topography of the City of Bonn from the Middle Ages to the End of the Electoral Period , p. 124, (Diet A 4, 164 b) and 665/1680, old signature: Kurköln II No. 1759

- ^ Josef Dietz in: Topography of the city of Bonn from the Middle Ages to the end of the electoral era , p. 128, Diet A 4, 189 a

- ^ Josef Dietz in: Topography of the City of Bonn from the Middle Ages to the End of the Electoral Period , p. 128, (Diet U 68)

- ↑ Josef Dietz in: Topography of the City of Bonn from the Middle Ages to the End of the Electoral Period , p. 128, (Diet A 4, 192 b and 193 a, 193 b)

- ↑ Josef Dietz in: Topography of the City of Bonn from the Middle Ages to the End of the Electoral Period , p. 124, (Diet A 4, 164 b) and 665/1680, old signature: Kurköln II No. 1759

- ↑ Hanna Stommel (arrangement): Sources on the history of the city of Erftstadt. V. Volume, Erftstadt 1998. No. 2700, pp. 58-59

- ^ Josef Dietz in: Topography of the City of Bonn from the Middle Ages to the End of the Electoral Period , p. 235 f

- ↑ Josef Dietz in: Topography of the City of Bonn from the Middle Ages to the End of the Electoral Period , p. 124 (old signature: Kurköln 34/1, 382)

- ^ Paul Clemen: The art monuments of the Rhine province . Volume 5: The art monuments of the city and the district of Bonn. 1905, section Sechtem p. 366.

- ↑ Josef Dietz in: Topography of the City of Bonn from the Middle Ages to the End of the Electoral Period , p. 124, (Ku 34 2)

- ↑ Josef Dietz in: Topography of the City of Bonn from the Middle Ages to the End of the Electoral Period , p. 160

- ^ Eduard Hegel, The Napoleonic Church Organization , in Bonn churches and chapels . P. 9 ff

- ^ Entry in the Bonn street cadastre