Liblar

|

Liblar

City of Erftstadt

Coordinates: 50 ° 48 ′ 49 ″ N , 6 ° 48 ′ 51 ″ E

|

|

|---|---|

| Height : | 94 m above sea level NHN |

| Area : | 12.82 km² |

| Residents : | 13,315 (March 31, 2018) |

| Population density : | 1,039 inhabitants / km² |

| Incorporation : | 1st July 1969 |

| Postal code : | 50374 |

| Area code : | 02235 |

|

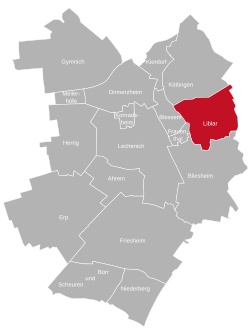

Location of Liblar in Erftstadt

|

|

Liblar is a district of Erftstadt in the Rhein-Erft district .

location

The place is on both sides of the federal highway 265 on the southern slope of the Ville on the edge of the Rhineland Nature Park and the Jülich-Zülpicher Börde . The neighboring districts are Köttingen in the northwest, Blessem and the small Frauenthal in the southwest and Bliesheim in the south. Beyond the Ville are the cities of Hürth and Brühl .

Neighboring places

| Dirmerzheim and Gymnich | Köttingen and Kierdorf | Huerth |

| Blessem and Lechenich |

|

Bruehl |

| Friesheim | Bliesheim and Weilerswist | Walberberg and Bornheim |

history

Roman time

The verifiable but unwritten history of the place Liblar begins in Roman times . This is evidenced by ceramics from the Roman era that were recovered in several places in today's location , the type and abundance of which suggest a settlement near the Römerstrasse Trier-Cologne , now called Agrippa-Strasse Cologne-Trier .

middle Ages

First mention and interpretation of the name

The parish Liblar was first mentioned as such with the name "lubdelare" in the High Middle Ages around 1155 in a handwriting of the Deutz Abbey and the place itself as "lublar" in 1197 on the occasion of an exchange of goods between the knight Wilhelm Schilling (Solidus) and the Cologne resident Archbishop Adolf I for the Schillingscapellen monastery .

Liblar is one of the –lar places. According to Heinrich Dittmaier , the final syllable -lar (old Franconian hlar ) of the place name denotes a pasture area enclosed by a hurdle or scaffolding , which was usually in the corner of a river mouth. The first syllable of the name lub- refers to a brook Luba flowing into the Swistbach (today Liblarer Mühlengraben).

Accordingly, Liblar means: settlement with a cattle pen on the Luba.

Village and Motte Spurk

To the southeast of Liblar, on the outskirts of the Ville, was the submerged place Spurk. In the 12th and 13th centuries there lived several pottery families who made ceramics in the way they were made in the pottery workshops in Pingsdorf . During excavation work in the 1930s, large amounts of pottery waste as well as false fires and furnace residues were discovered south of the station .

At today's Kapellenbusch, about 700 m east of Schloss Gracht , there was a moth in the Middle Ages , whose elliptical hill with the surrounding moat can be seen on a map of the Liblar district . It was near two important roads, the Cologne – Zülpich road , the former Roman road Trier – Cologne , and the Bonn-Aachener Heerstraße , which ran from Bonn via Brühl through the Ville to Lechenich and on to Aachen .

Clergy and noble property

Several monasteries and monasteries owned in Liblar and Spurk, including around 1230 the St. Andreas monastery in Cologne , most of which was lost over time. Also the monastery and later Dietkirchen monastery in Bonn , whose court was first mentioned in Liblar in 1293, as well as the Frauenthal monastery and, from 1450, the Marienforst monastery as its successor .

Even noble families like the family of Gymnich had possessions in Liblar and Spurk that have been mentioned 1276th In addition to the “Stadelhofstatt” of the monastery and later Dietkirchen Abbey with court jury and court court, there was another manor with court jury and court court in Liblar , Mr. Emunds Gryns Gut.

After the middle of the 15th century there was only the Fronhof of Dietkirchen Abbey, whose fiefdom , the Grachter Hof, awarded in the 15th century , went to the Knights of Buschfeld on Haus Buschfeld and their heirs, who called themselves Wolff Metternich zur Gracht . The Buschfelds built Gracht Castle there around 1500.

Since the 15th century, the farm belonging to the former Spurker Castle was given as a fief of Dietkirchen Abbey. It came to the von Gymnich family through the noble Wolff von Rheindorf and von Buschfeld families.

Modern times

Destruction by war

Over the centuries, Liblar and Spurk were repeatedly affected by armed conflicts. During the feuds between Count Engelbert von der Mark and Archbishop Friedrich and between Duke Adolf von Berg and Archbishop Dietrich von Moers , Liblar was devastated in 1391 and 1416.

The villages were also affected by the Truchsessian War in 1586. Although the damage to the outer bailey of the Gracht house was repaired in the following years, the burnt-down courtyard of Dietkirchen Abbey was rebuilt through the Halfen, but the burned houses in the hamlet were rebuilt Spurk and the destroyed buildings of the Spurker Hof were not rebuilt. The feudal lord, the abbess of Dietkirchen, gave her permission to sell the Spurker Hof in 1591 with all rights from Johann von Gymnich zu Vischel to Hermann Wolff Metternich.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, Messrs. Wolff Metternich acquired their courtyards and farmland from the owners in Spurk and combined these properties and acquisitions in Liblar with the ownership of the Grachter Hof in the same place.

The streets Am Spürkerkreuz, Im Spürkergarten and Spürkerau in Liblar are reminiscent of the place Spurk, which was also called Spürk in modern times.

Living conditions of the inhabitants

For centuries Liblar formed together with Spurk and Köttingen an honor in the Electoral Cologne Office of Lechenich . In this the electoral sovereignty applied, including the noble house of Buschfeld and the Bremerhof. The rights and duties of the villagers were laid down in a wisdom called a farmer's book and were announced to the residents of the Herren geding in Lechenich, and later by Messrs Wolff Metternich on the Herrengeding in Liblar. In the Liblar Honschaft between 1628 and 1629 at least 12 women were accused of being witches and handed over to the electoral court in Lechenich for judgment.

The majority of the inhabitants, like the inhabitants of the area, lived from agriculture , which in most cases only consisted of a few acres of farmed land and the keeping of a few animals.

After the survey carried out on behalf of Elector Maximilian Heinrich and the subsequent tax registration of the houses and lands in 1662, the Liblar community had 53 farmhouses and some building sites. In Liblar there were 39 houses, in Spurk 2 and in Köttingen 12. Only the Fronhalfe von Dietkirchen and the Fronhalfe von Mariengraden in Bliesheim, who were wealthy in Liblar, had larger property. Haus Gracht was tax-free as a noble seat ("noble lake"), which also included the Spurker Hof with 180 acres and the mill bought by the Marienforst monastery in 1627.

Like the other places in today's city of Erftstadt, Liblar suffered from frequent marches of troops in the 17th and 18th centuries, during which forage deliveries and services were demanded that had to be provided by the residents and lasted until the end of the Seven Years' War in 1763.

Fronhof of Dietkirchen Abbey

According to a description from 1668, the Fronhof was between the church and the public road. To this court belonged 20 smaller court estates given as a fief, the owners of which, as court jury members, had to obey a court court of the Fronhof, or to represent such a jury. The court in session included the mayor, the court jury, a clerk and the court messenger, all of whom were sworn in. Real estate matters were negotiated before the court court of the Fronhof , in which a Kurmut had to be paid when a new fiefdom was awarded, which consisted of a horse-drawn horse. The rights of the monastery and the duties of the court shorn were recorded in a court demonstration that was generally presented four times a year at court court days. The half of the Fronhof was obliged to keep the breeding cattle and feed the electoral hunters.

Subordinate rule of the barons and counts Wolff Metternich

In 1630 the Honschaft Liblar came with the high jurisdiction, with the customs law, income, services and other accessories in pledge possession of Johann Adolf Wolff called Metternich to the canal . He received this from 1633 for himself and his descendants as subordinate rule with the condition not to tolerate any Protestants in Liblar. Johann Adolf I confirmed his status as Herr zu Liblar by expanding the Gracht headquarters into a representative castle in 1658.

The court of the subordinate Liblar existed until the time of the French administration. It was run by a trained lawyer and an imperial notary acted as a clerk. In the subordinate rule of Liblar, orders from Messrs. Wolff Metternich and the electoral decrees were strictly observed and violations were severely punished.

New construction of the Church of St. Alban

For centuries, Liblar formed a parish together with Spurk and Köttingen . Today's Church of St. Alban was built for members of the parish between 1669 and 1670 with significant support from the Wolff Metternich family , with its tall, pointed church tower being visible from afar.

French time

The occupation of the areas on the left bank of the Rhine by French revolutionary troops in 1794 ended in 1797 with the Peace of Campo Formio . The occupied area was then annexed and, on behalf of the French government, in 1798 the administration and justice system were redesigned based on the French model. The old territories and dominions, including the subordinate Liblar, were abolished. After the constitutional amendment carried out by Napoleon in 1800 and the introduction of the prefecture , the administration was changed. The administrative districts consisted of departments , arrondissements , cantons and Mairien . The cantons were judicial districts and the seat of the peace court. The municipality Liblar together with the municipalities Bliesheim and Kierdorf formed the Mairie Liblar in the canton Lechenich , Arrondissement de Cologne , Département de la Roer . In the Peace Treaty of Lunéville in 1801, the four Rhenish departments, which had existed since 1798, were recognized as French national territory. When the population was recorded in 1801, 563 people, 334 adults and 129 children lived in Liblar. Without the residents of Haus Gracht, more than 90 families lived in the village, usually in households of four to nine people. Of the heads of households, 40, almost half, were designated as workers (ouvrier), 12 as owners of small quarries , and two were small Jewish traders. In 1802, secularization was carried out in the four departments on the left bank of the Rhine that had existed since 1798 . The basis was the Concordat concluded between Napoléon Bonaparte and Pope Pius VII . As a result of secularization, the Fronhof and other possessions of the Dietkirchen Abbey, the lands of the Marienforst Monastery and the “Turffgruben” of the Elector “above Spurk” were nationalized and then sold between 1807 and 1812.

Prussian time

Administration and Infrastructure

The administrative unit "Mairie" remained in Prussian times as a mayor's office and since 1927 as an office.

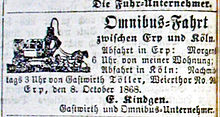

The infrastructure was improved in the 19th century by building or expanding roads. The Brühler Chaussee , built in 1831 and running from today's Carl-Schurz-Straße through the Ville to Brühl, created an easily navigable connection to Brühl. From 1854 to 1856, the Luxemburger Straße leading through Liblar was expanded as a district road. In 1840 a postal expedition was opened in Liblar , which was one of several stations on the overland route to Cologne or in other directions. It was operated by private entrepreneurs using horse - drawn carriages , and later also by horse-drawn buses . Kraftpost buses have been running the Cologne - Liblar - Lechenich - Gymnich and Brühl - Liblar - Lechenich routes since 1926 .

Through the connection to the Cologne - Euskirchen - Trier railway , which was put into operation in 1875, the place received a railway station equipped with a representative station building (similar to the "Kaiserbahnhof" Kierberg), which significantly improved the previous transport connections.

Liblar received further modern technology from this time by setting up a telegraph station . A water pipeline from Brühl - Liblar that was laid in 1901/02 represented an elementary step forward, which significantly improved the hygienic standard. Around 1910/11 Liblar was connected to the electrical power grid, so that in addition to the "electrical light", modern devices and machines were introduced.

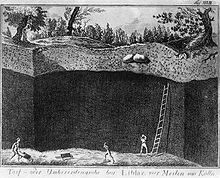

Brown coal

Lignite occurred on the slopes of Florida, especially in the short stream valleys to day and could easily pick and spade as Turff and Cologne Umbererde be reduced still manually Klütten were molded and dried used as fuel. The first pits and cliffs as heating material are attested to in 1730. In 1824, under Prussian rule, the first concession was granted under Prussian mining law (regardless of land ownership) for the "Concordia" mine, which houses the former electoral pits of Anton Wings, the pit of Count Wolff Metternich, the community of Liblar and other small pits above Liblars on Luxemburger Strasse were united. During the period of industrialization and after the construction of the first briquette press by Carl Exter (1855), open-cast lignite mining developed as the most important branch of industry in the southern Rhenish lignite mining area for around 100 years . Many workers from Liblar and the places around worked in the last under the company Rheinbraun summarized pits pit and briquette Concordia South , the Concordia North (1897 Zieselsmaar had been separated), pit and briquette Liblar (since 1899) and pit Donatus ( briquette 1892). The Donatus mine was named after the Zülpich magistrate Friedrich Doinet , who applied on September 20, 1857 to use a 2,600 hectare brown coal field in Liblar.

Effects of the rail connection

After the construction of the Cologne-Trier railway line, it was possible to transport raw coal and briquettes by rail. In Liblar these goods were loaded onto 16 tracks. Sidings connected the mines and works with the main tracks and the two small railways, the Euskirchener Kreisbahn (1894/95), which was set up for both passenger and freight traffic and transported agricultural products such as sugar beet, but above all coal from the Donatus mine , and the Mödrath-Liblar-Brühler Eisenbahn (1899/1901) built and operated by the Westdeutsche Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft , which mainly transported coal. After the laying of a third rail as a standard gauge in 1904, which enabled the connection to the Reichsbahn in Liblar, the Mödrath-Liblar-Brühler Eisenbahn took up passenger traffic. The Euskirchener Kreisbahn had a shunting yard and an office building. Like the platform of the Mödrath-Liblar-Brühler Railway, the terminus was in front of the Reichsbahn station building erected in 1874.

West German machine factory

After the Mödrath-Liblar-Brühl line went into operation , the West German Railway Company built a railway repair shop in Liblar, in which the locomotives and wagons of several small railways could be repaired. This large facility, the "West German Machine Factory", created many new jobs where a large number of workers from Liblar and the surrounding area earned their living.

Donatusdorf

The extended lignite mining was no longer feasible due to the potential of local miners, so that additional workers were required through foreign recruitment. In order to offer workers and their families adequate living space in addition to secure jobs, the Donatus mine had uniformly designed two-story houses built, the first of which were built between 1890 and 1898 in what is now Donatusstrasse and its branch roads and were called "Donatusdorf". This was followed by houses in Bahnhofsstraße and in 1904 a row of houses "on the Heidebroich". In 1921, residential buildings, mostly civil servants' apartments, were built on Schlunkweg and the vacant lots in Heidebroichstrasse were closed. The government master builder Mertznich, who also took over the construction management, provided the design for the development.

In 1922, the Prussian Ministry of the Interior approved the resolution of the Liblar municipal council and the following application to the regional president that the districts of Donatusdorf, Heidebroich, Schlunkweg and Bahnhofstrasse belonging to the Liblar municipality were given the designation "Oberliblar".

schools

As under French administration, school lessons were continued by the sexton teacher, who had already been active in the electoral era, and whose teaching activities were not changed by the general compulsory schooling of 1825, which was introduced in Prussian times. It was not until 1828 that the lessons were held by the "candidate" (candidate for a teaching post) Christian Schurz, the father of the German-American Carl Schurz , who had attended the teachers' seminar in Brühl and held the lessons until he was replaced in 1833.

At that time, 117 children to be taught in a school hall in the parish hall would have had to attend school, but only a few of them were younger. Most of them did not attend school and were already working in the coal mines as adolescents.

After compulsory schooling was fulfilled by most of the students from the middle of the 19th century, the community tried to improve school conditions. In 1847 she acquired the Schurz property as a schoolhouse, but after a few years the premises were no longer sufficient for the increased number of students. The dance hall adjoining the school building was prepared and provided space for two more school halls. Previously, a demolition and a new building at a different location proposed by the municipality in 1852 had been considered, but was not implemented because, according to a report by the building councilor Ernst Friedrich Zwirner, repairing the dance hall with the division into two classrooms was sufficient. It was not until 1876 that the former dance hall was demolished and a new brick school building was erected on the site.

The lignite industry caused a strong increase in the population and thus also caused the number of students to rise sharply, so that Köttingen and Oberliblar also had their own schools. In Liblar itself, a new school building was built in 1903 at the junction between Brühlerstrasse and Hauptstrasse (today Carl-Schurz-Strasse), which was expanded in the following decades.

As the number of pupils in Oberliblar continued to rise sharply, in 1910 the community built a new school building with four halls in Heidebroichstrasse for the children of “Donatusdorf” and “Heidebroich”, which also housed a class from the one-class Protestant school established in Liblar, which was previously had been taught in the old school building.

graveyards

In 1840 the churchyard around St. Alban's church was abandoned and the community cemetery on Köttinger Strasse was created on the property acquired by the community.

The Jewish community received a cemetery on Schlunkweg in 1877, for which Count Wolff Metternich donated land that could no longer be used for agriculture on the condition that it was used as a cemetery.

Weimar period

After the First World War and the end of the Wilhelmine era, Liblar was subject to the British occupation in 1919 and French occupation from 1920 to 1926 in accordance with the provisions of the Versailles Peace Treaty , which among other things stipulated the occupation of the area on the left bank of the Rhine . The orders of the occupation authorities brought restrictions for the citizens but also security from revolutionary unrest. As a result of the reparations claims , which the German government rejected as being impossible to meet , Moroccan soldiers were quartered in Liblar in 1923 and occupied the lignite mines. They left Liblar in 1924 after the reparations payments were resumed.

The advancing currency devaluation has a negative effect. The inflation and the introduction of the pension Marks the end of 1923 (1924 by the Reichsmark replaced) brought many families to their savings. After the introduction of the new currency , the economic situation improved for a few years.

The brown coal factories, which had risen to become the largest regional employers, laid off parts of their workforce by the early 1930s due to the global economic crisis in 1929 and due to a lack of demand for their product, briquette , which caused many of the men to become unemployed and “stamped”. In Liblar, a branch of the Brühl employment office had been set up on Brühler Strasse, to which unemployed people had to report regularly in order to receive their support. Others took on odd jobs, including farming and forestry, to support their families. Since many of the families planted a small kitchen garden and kept pets, the greatest need could be averted. Westdeutsche Maschinenfabrik was one of the few large companies in the region that did not suffer any loss of orders during the economic crisis. Under the new management (since 1919) she had specialized in the repair of steam locomotives.

time of the nationalsocialism

According to old tradition, the Liblar population was close to the Center Party, which received over 50% of the vote in the 1930 elections and almost 40% in March 1933. In the workers' village of Oberliblar too, over 30% chose the center. The SPD was just as strong in Oberliblar, but its share of the vote fell from 32% in 1930 to 24% in March 1933. In the village of Liblar, the SPD received 15.9% of the votes cast. In 1933 the NSDAP gained only 12.9% in Liblar and 10.3% in Oberliblar.

After the “seizure of power” in the Reichstag, the local branch of the NSDAP became very active and, like in other places, influenced the lives and thoughts of the residents through skillful agitation . The NSDAP headquarters of the Liblar local group and a rural vocational school for girls were housed in a house on Brühler Strasse, the “Brown House” (officially “Adolf Hitler House”), which was acquired by the community.

The influence of this party had also increased in Liblar in a few years, so that the Jewish families living in the village could be harassed with impunity. After apartments and shops had been demolished in November 1938 , four of the five remaining families moved to Cologne to go into hiding in the city. In 1942 they were also transported from there to concentration camps and murdered, only two people survived.

The population was directly affected by the effects of the Second World War . At the beginning of January 1945, 15 people died in Oberliblar in an attack on the Reichsbahn facilities there, in which the nearby buildings were hit, and by the low-flying gunners firing on-board weapons. Shortly before the American troops marched into Liblar, parts of St. Alban's Church were destroyed by mines by German soldiers.

Changes after World War II

Churches and denominations

The church that defines the townscape of Alt-Liblar was and is the Catholic Church of St. Alban , whose damage suffered in the Second World War was repaired in 1950.

At the turn of the century, more and more people moved to the new Oberliblar district thanks to the jobs and benefits created by the lignite industry. Most of them were new citizens of the Catholic denomination, so that as early as 1901 it was considered to build a church in the growing part of the town. The outbreak of the First World War , however, prevented the start of construction, which was planned for 1914. Therefore, since 1918, services and mass have been held in a school room on Sundays. In 1925, a wooden barrack was built as an emergency church, which became a makeshift facility in which services were held until after the Second World War. In 1952/53 the community was able to build a new building and realized a simple brick church, which was consecrated to the patron saint of miners St. Barbara . The windows designed by the Trier glass painter Jakob Schwarzkopf (* 1926 in Koblenz) in 1967 are worth seeing . as well as tabernacle and baptismal font, both works by Jakob Riffeler .

The new citizens of the Protestant denomination were looked after by the parish of Brühl at that time. They had founded a church building association as early as 1911, to which the Liblar mine under mine director Watzke made land available after the First World War. In this work the architect Deichmann was one in Oberliblar 1925/26 then under the supervision church built predominantly financed through shares of the club members and donations from the pits. In 1949 the parish, which is now called the Friedenskirchengemeinde, became independent from Brühl and became an independent parish.

The Jewish community never had a place of worship in Liblar. The cemetery of the Jewish community on Schlunkweg, which was destroyed in 1940, was restored in 1961 by the Liblar civil parish and new gravestones and a memorial stone were erected.

End of brown coal stocks

Since the end of the 1930s, the end of lignite mining and processing in the Liblar area was foreseeable when the Concordia Liblar mine (Concordia Süd) had to cease briquette production in 1938. When the coal reserves of the Donatus mine were exhausted in 1944, the Roddergrube took over the facility and transported its coal to Donatus for processing. The attempts by the Donatus mine to extract coal using civil engineering from 1947 to 1952 proved to be unprofitable and were discontinued. On July 1, 1959, the Donatus mine was closed. In 1961 the Liblar mine followed, which had also been supplied with coal for briquette processing from the Rodder mine since 1957.

After the end of the briquette processing, the small railways had lost their main task and ceased operations in 1959 (Euskirchen - Liblar district) and 1961 (Mödrath-Liblar-Brühler Kreisbahn).

Connected with this was the end of the "West German Machine Factory", which had enjoyed a boom with repairs to steam and diesel locomotives until after the Second World War. As a fundamental modernization was too expensive for the operator, the Klöckner Group , which had taken over the machine factory in 1958, it was closed in 1967.

Increase in population and built-up area

Liblar was affected by two radical changes in the post-war period. On the one hand, there was the end of lignite mining and the closure of the associated factories; on the other hand, there was a sharp increase in the population, which was not the case in any of the other districts of Erftstadt.

The first increase came from the displaced persons , who were given building land to build their own homes and developed.

The available building land resulted from 1957 onwards from the extensive lands of the Counts von Wolff Metternich's family acquired by the Liblar community at that time, who also sold Gracht Castle to the community. Since the end of the 1950s, the community began to develop the site, triggering a real “building boom”.

Initially, the development expanded strongly in the direction of Oberliblar, so that both districts grew together. As a result, only the place name Liblar has been used since 1964 and the town council decided to remove the place name signs “Oberliblar”, but the name Oberliblar remained in the language of the local population. The new development continued in the south in the following time.

The influx of numerous new residents, who mainly work in Cologne or the industrial plants in the Cologne area, made Liblar the most populous municipality in the former northern district of Euskirchen.

Since there were many families with children among the newcomers, the premises of the elementary school in Alt-Liblar were not sufficient for the school-age children despite the extensions. Although a secondary school was set up in 1963 as required, the community felt compelled to have new school buildings built near Bahnhofstrasse in 1963/64, which were later expanded into a school center. The previous Protestant school, which had been a community school since 1966, was also housed there. Of the primary schools and a secondary school that remained after the school reform in 1968, a primary school in Alt-Liblar and a primary school in Oberliblar as well as a secondary school remained.

administration

After the state of North Rhine-Westphalia was founded in 1946, the Liblar Office continued to exist until the municipal administrative reform in 1969.

In the following years, the war damage was repaired in Liblar. In the years 1959–1969 new residential areas were developed, the sewer system improved, new schools built and the municipal roads expanded.

After a decision by the state government of North Rhine-Westphalia, a regional reform was carried out on July 1, 1969, which was concluded on January 1, 1975. During this reform, several smaller municipalities were merged into a few large administrative units. In the northern district of Euskirchen, this affected the city and the Lechenich office, the Liblar office, the Friesheim office and the Gymnich office, which now formed a new administrative unit. During the preliminary considerations, some Liblar politicians pleaded for a new neutral name under the collective term "Erftstadt", which the legislature corresponded to on the grounds that "the area between Lechenich and Liblar would be shaped by the Erft landscape". The development opportunities of the new community would be in the Lechenich / Liblar area. As a result, a representative urban center was to be created, which would connect Lechenich with Liblar. The plan to merge Liblar and Lechenich with a new center on both sides of the Erft was abandoned in 1976.

Population development

| year | Residents |

|---|---|

| 1871 | 1070 |

| 1925 | 3337 |

| 1959 | 4300 |

| 1961 | 6946 |

| 1969 | 9269 |

Of the 4,300 inhabitants counted in 1959, the village Liblar accounted for 2,100 and Oberliblar 2,200.

Today's district Liblar

Old town center

The old town center Liblar stretches along Carl-Schurz-Straße and is dominated by the Church of St. Alban, the Fronhof and the grounds of the Gracht Palace with its historic park, which is accessible to all citizens.

At the level of the church, roads branch off to Köttingen, Kierdorf and past Buschfeld to Bliesheim. The expansion of the B 265n as a bypass road and the redesign of the Carl-Schurz-Straße as a traffic-calmed zone relieved through traffic. Changes to St. Alban and Fronhof, Viry-Chatillon-Platz and the redesign of Marienplatz improved the quality of living and will also stimulate the business situation in the old district.

In Carl-Schurz-Straße and in the side streets there are shops for daily needs in retail and specialty shops. There are also cafes and restaurants, a post office, a bank and a petrol station, lawyers and the office of Bauverein Liblar. There is a regular weekly market on Viry-Chatillon-Platz.

A commercial area is located on the outskirts in close proximity to Köttingen.

New Liblar

Residential park

The wishes of the urban planners of the time were realized on the area in the south of Liblar, which was designated as a future residential area and was built on in the style of a modern “residential park”. Since 1967, a new mixed-building settlement with plenty of greenery has been built in several construction phases near Bliesheimer Straße on both sides of the newly laid out Theodor-Heuss-Straße. This contained high-rise buildings, row houses and multi-storey detached single and multi-family houses or bungalows . Three twelve-storey high-rise buildings, each with around 80 residential units, were built on the streets that were also new, Konrad-Adenauer-Strasse and Bertolt-Brecht-Strasse, and two more near the “Bürgerplatz”. All of them, including the row houses, were built according to a modular principle with prefabricated structural elements made of exposed aggregate concrete. These prefabricated buildings, recognizable from afar, shaped the new residential area, which stood out from the rest of Liblar through its architecture and gave the new center an urban character.

The Bürgerplatz on Theodor-Heuss-Straße forms a small center with a few shops and a weekly market there.

RAF hiding place during the Schleyer kidnapping

As part of the preparations for the Schleyer kidnapping , RAF terrorist Monika Helbing rented an apartment in the Zum Renngraben 8 skyscraper in June 1977 . The RAF deliberately chose the anonymity of a high-rise building that was equipped with an underground car park and was located near a motorway junction. After his kidnapping on September 5, 1977, the employer's president Hanns Martin Schleyer was held there for 10 days.

Hill house

The striking pyramid-shaped "hill house" on Theodor-Heuss-Strasse / Im Spürkergarten is remarkable. It was completed in 1975 and shows another variant of the architecture of the urban development implemented in the new Liblar, the terrace house construction. The construction of the eight-storey residential building, which was designed by the Liblar architect Hans Oberemm, was funded with public funds and comprises 76 residential units in its tapering floors of different sizes. Oberemm himself describes the apartments built in this design as single-family houses stacked on top of one another. The house, which was built using a combination of brick and concrete, reaches a height of around 30 meters, and its base is based on a uniform grid. Its floor plan is reduced by a few grid squares from bottom to top, so that a pyramid shape is created. There are 14 apartments on the ground floor and 16 apartments on the first floor, and two penthouse-like units remain in the last. The individual floors are traversed in the middle by an elongated corridor, which serves as access to the individual apartments. Due to the way they were built, all apartments were given terraces, the balustrades of which were laid out as wide troughs, which are suitable for planting with decorative wood, flowers and bushes. There are several shops in the basement of the house. A “social room” was set up for the residents, which can be used as a children's playground, for neighborhood meetings and as a party room.

shopping mall

The focus of the business world has shifted to the new service center with the “Holzdamm shopping center” (EKZ), which was created in 1978, at “Am Holzdamm”, with specialty shops including a large supermarket, a hardware store, bank branches and law firms . The residential area created there grew together with the existing settlement on the other side of Bliesheimer Straße.

town hall

The newly created quarter on Holzdamm is also the location of the Erftstadt town hall, which was completed in 1989 . Almost all administrative departments are located in it.

The elected representatives of the parties take care of the interests of the Liblar district in the city council. Local mayor is Martin Kolbe (as of April 2018), who represents the interests of the largest district with 13,315 (as of March 31, 2018) inhabitants.

Fire and rescue station

The full-time fire and rescue station of the city of Erftstadt and the fire fighting group Liblar of the volunteer fire brigade have also been located on the Holzdamm since 1992.

Medical care

There are specialist practices and pharmacies in Alt-Liblar, but the majority of general medicine practices, specialists in most specialist disciplines and pharmacies are in the new district.

For special illnesses and operations , the nearby “Marienhospital” Frauenthal clinic , which was developed from the Münch Foundation , with a dialysis center and the specialists in the local medical center can be visited.

Educational institutions

The Donatus Elementary School has existed on Theodor-Heuss-Strasse since 1973 and has been attended by all Liblar students of this age group since 1978. The school was built according to plans by the architect Hans Oberemm.

The school center is located in the old part of the village, and a grammar school was added in 1974. Mainly pupils from Liblar, Bliesheim, Blessem, Köttingen and Kierdorf attend the public secondary schools.

The "Freie Waldorfschule Voreifel", a private school near the train station, which has existed since 1990, is also attended as an offer school by many non-Erftstadt students.

Municipal and denominational day-care centers , as well as “day-care centers” run by parents' initiatives, relieve working parents.

Cultural Opportunities

The adult education center (VHS) Erftstadt on Marienplatz in the former elementary school building offers a wide range of events and courses from various subject areas.

The municipal Bernd-Alois-Zimmermann-Musikschule, which has existed since 1970 and had been housed in the building of the former elementary school in Oberliblar since 1974, was able to move into the premises in the “Kultur- und”, which was built next to the fire and rescue station and completed in December 2013, in January 2014 Musikhaus Anneliese Geske ”. Citizens interested in culture have the opportunity to take part in events organized by the art association, the cultural group or the adult education center or to use the wide range of the city library . Events and activities of cultural associations such as the Carl-Schurz-Kreis or Förderverein Schlosspark are initiated by citizens who have moved here over the past decades.

Events organized by cultural associations such as the Schau-Fenster Künstlerforum, which was awarded the Rhein-Erftkreis Culture Prize in 2004 and the Carl-Schurz Medal in 2011, and the Erftstadt Cultural Area take place in both Liblar and Lechenich.

Support groups or groups of friends in the twin cities maintain contact with the cities of Wokingham (GB, since 1977), Viry-Châtillon (France; since 1980) and Jelenia Gora (Poland; since 1995).

societies

The St. Sebastianus Schützenbruderschaft Liblar 1736 eV is the oldest local club. The carnival presents itself in two carnival societies, the Fidelen Narrenzunft Liblar 1936 and the Klüttefunke Oberliblar 1956.

In addition, there is a scout group of the German Scouting Association Saint Georg who meet in the rooms of Saint Barbara.

freetime and sports

The football club SC Fortuna Liblar 1910 is a club with an old tradition. Other successful sports clubs with many members almost all came into being after the Second World War, such as the canoeing club Wassersportfreunde Liblar , sailing club Ville and the fishing club Liblar, which own club houses on Lake Liblar .

The Aktivclub Erftstadt (ACE) offers a wide range of cultural and leisure events aimed primarily at senior citizens.

Biking and hiking trails lead along the Erft and through the Ville with its lakes created by the mining of brown coal.

The Liblarer See offers bathing opportunities as a bathing lake . Liblar has an indoor pool in the Holzdamm shopping center.

The Hockey is operated in Erftstadt since 1974th Almost 200 players are active in the hockey department of the Sportgemeinschaft Erftstadt 1970 eV.

Transport links

The Erftstadt station of Deutsche Bahn AG is located in Liblar on the Eifel line Cologne – Euskirchen – Trier .

The former Liblar station building, which was still built by the Rheinische Eisenbahngesellschaft , had to be restored in the 1960s. Although efforts were being made to preserve it as a memorial, the building was demolished in 1981 on behalf of the German Federal Railroad shortly before the official confirmation was received. In 1990 the station was renamed from "Liblar" to "Erftstadt".

In autumn 2015, all platforms were demolished and rebuilt a little higher to match the height of the wagon floors. Instead of the platform crossing, an underpass was built to access the track in the direction of Cologne. The following pictures show the old condition (until 2015).

City and regional bus connections

The Erftstadt stop is a hub for the buses of the Rhein-Erft-Verkehrsgesellschaft . The bus station on Schlunkweg, at the corner of Bahnhofstraße, is served by the buses on the 979 Hürth – Erftstadt Bahnhof – Lechenich – Zülpich, the 920 Erftstadt Bahnhof – Lechenich – Kerpen, the 990 Lechenich – Erftstadt Bahnhof – Brühl, the 955 Erftstadt Bahnhof– Türnich – Horrem and the 977 Erftstadt Bahnhof – Türnich – Frechen line, where you can change trains in other directions.

Road network

The highway interchange Erftstadt of A 1 / 61 is located directly on the western edge. The B 265 serves as a feeder there. There is no longer a direct connection to Brühl, as Brühler Chaussee was destroyed during lignite mining.

Attractions

- Catholic Parish Church of St. Alban

- Castle canal

- Buschfeld House

- Buschfelder Mill

- Landscape protection area Liblarer See

- former Jewish cemetery

Personalities

The most famous Liblarer is Carl Schurz , born on March 2, 1829 in the outer bailey of Schloss Gracht , who took part in the revolution of 1848/49 , later emigrated to America, and there became a more or less successful troop leader of the German volunteers in the American Civil War . He later became American Secretary of the Interior under Rutherford B. Hayes (1877–81).

- Franz Arnold von Wolff-Metternich zur Gracht (1658-1718), Roman Catholic Bishop of Münster and Paderborn

literature

- Heidi and Cornelius Bormann : home on the Erft. The rural Jews in the synagogue communities Gymnich, Friesheim and Lechenich Kerpen 1991. ISBN 978-3-9802650-3-4

- Heinrich Dittmaier : The (h) lar names . Low German Studies 10. Cologne 1963, ISBN 978-3412241636

- Manfred Faust (Ed.): Liblar in old views , European Library, Zaltbommel (NL), 2000, ISBN 90-288-6630-2

- Interest group 850 years of Liblar e. V. (Ed.): Liblar 1150-2000 . The book on history. Liblar 1999

- Gerhard Mürkens: The place names of the Euskirchen district . Euskirchen 1958

- Gabriele Rünger: Who voted for the NSDAP? In: History in the Euskirchen district. 1987

- Bernhard Schreiber: Archaeological finds and monuments of the Erftstadt area . Erftstadt 1999 ISBN 3-9805019-4-9

- Volker Schüler , Manfred Coenen: The Donatus Briquette Factory 1890-1959 . Historical representation of a briquette factory in the Liblar area. Documenta Berchemensis historica; Vol. 5. Frechen 2004

- Peter Simons : Liblar, history and local history of the old imperial county in the Electorate of Cologne . Liblar 1956

- City of Erftstadt (Ed.): Yearbooks of the city of Erftstadt

- Hanna Stommel: Liblar , in: Frank Bartsch, Dieter Hoffsümmer, Hanna Stommel: Monuments in Erftstadt (loose-leaf collection) AHAG (ed.) Lechenich 1998–2000

- Karl and Hanna Stommel: Sources on the history of the city of Erftstadt 5 volumes. Erftstadt 1990–1998

- Karl Stommel : The French population lists from Erftstadt . Erftstadt 1989

- Fritz Wündisch : About Klütten and Briquettes . 2nd Edition. Brühl 1980. ISBN 3-922634-00-1

Individual evidence

- ↑ http://www.erftstadt.de/web/infos-zu-erftstadt/die-stadt-in-zahlen

- ↑ a b c Bernhard Schreiber: Archaeological finds and monuments of the Erftstadt area. Erftstadt 1999. Pages 91–102 and Page 157

- ↑ HAStK inventory of Deutz Abbey Repertories and Manuscripts 2, copy of the lost Codex thiodorici

- ↑ Parish archive Buschhoven document 1197 and Th. J. Lacomblet, document book for the history of the Lower Rhine Volume I No. 558

- ^ Heinrich Dittmaier, Die (h) lar names. Low German Studies 10. Cologne 1963. Pages 41–60 and Pages 84–107

- ^ Gerhard Mürkens: The place names of the district of Euskirchen. Euskirchen 1958. Page 20

- ↑ Erftstadt City Archives E02 / 102

- ^ HAEK parish archive St. Andreas, files II 40

- ↑ HAStK Foreign Affairs 170b, published in Stommel, Sources for the History of the City of Erftstadt Volume I No. 178

- ↑ Landesarchiv NRW Düsseldorf holdings Kurköln II 1257

- ^ Richard Knipping, The Regest of the Archbishops of Cologne. Volume III No. 2686

- ^ Archive Castle Gymnich Certificate No. 83

- ↑ Landesarchiv NRW holdings Kurköln document No. 1266 and Landeshauptarchiv Koblenz holdings 54.32. Document No. 87 published in Stommel, Sources Volume I No. 720 and Volume II No. 1103

- ↑ Archive Zwolle (Netherlands) Archief Kasteel Rechteren Regest No. 2 and HAStK inventory St. Pantaleon deed No. 3/398, published in Stommel Quellen II No. 1110 and No. 1174

- ^ Landesarchiv NRW Düsseldorf inventory Dietkirchen Akten 17, sheets 7-36, published in Stommel, Quellen Volume II No. 935 and 1095

- ↑ Norbert Andernach, Regesta of the Archbishops of Cologne in the Middle Ages, Volume X. Düsseldorf 1987. No. 82 and Stommel, Sources, Volume IV, Addendum No. 881a

- ↑ Archive Schloss Gracht files 557 (house minutes)

- ^ Landesarchiv NRW Düsseldorf inventory Dietkirchen files 35c pages 154-159

- ↑ Archive Schloss Gracht Certificate No. 124

- ↑ Archive Schloss Gracht files 552-556

- ^ Archives Schloss Gracht files 552

- ^ Archive Schloss Gracht files 552 and Landesarchiv NRW Düsseldorf holdings Kurköln XIII 167

- ↑ Archive Schloss Gracht files 19

- ↑ Landesarchiv NRW Düsseldorf holdings Kurköln II 1152 p. 424-437

- ↑ Archive Schloss Gracht, files 21-24 (troop marches)

- ^ Landesarchiv NRW Düsseldorf inventory Dietkirchen files 35c

- ^ Archive Schloss Gracht documents No. 45, No. 46, No. 47 and No. 48

- ↑ Archive Schloss Gracht files No. 563

- ↑ Landesarchiv NRW Düsseldorf inventory Kurköln XIII 166

- ^ Landesarchiv NRW Düsseldorf inventory Reichskammergericht Q 60/72

- ^ Archives Schloss Gracht files 83, 84, 87

- ↑ Archive Schloss Gracht files 87

- ^ Wilhelm Janssen: Small Rhenish History. Düsseldorf 1997. page 262

- ↑ Max Bär: The administrative constitution of the Rhine Province since 1815. Bonn 1919. Page 42 ff

- ^ Karl Stommel: The French population lists from Erftstadt. Erftstadt 1989 pages 350–372

- ^ Wilhelm Janssen: Small Rhenish History. Düsseldorf 1997, p. 264

- ↑ W. Schieder (ed.): Secularization and mediatization in the four Rhenish departments, Canton Lechenich, pages 483-485

- ^ Wolfgang Drösser: Brühl. 2nd edition 2006. page 132

- ↑ Peter Simons: The development of the traffic system in the Euskirchen area. Supplement to the Euskirchener Volksblatt 6th and 7th year 1929 and 1930

- ^ Walter Kessler, Post in Liblar. In: Erftstadt City Yearbook 2002. Pages 111–113

- ^ Advertisements in the intelligence paper for Euskirchen and Rheinbach

- ↑ Archive Schloss Gracht files 53

- ↑ a b Fritz Wündisch: From Klütten and Briquettes. 2nd edition 1980. Pages 53-54, 64 and 156

- ^ Contract on the leasing of the concession to Carl Brendgen , the owner of a briquette factory in Zieselsmaar, by Ferdinand Reichsgraf Wolf Metternich dated November 6, 1897 and a supplementary contract dated April 11, 1902 in: Bert Rombach, Kierdorf, the cradle of the Rhenish lignite mining industry. Kierdorf 2008. Pages 98–100

- ↑ Michael Folkers, Three Companies and Three Railway Stations. In: Yearbook of the City of Erftstadt 1998. Pages 40–42

- ↑ Liblar station building. Retrieved September 25, 2017 .

- ^ A b c Michael Folkers: The West German machine factory in Liblar. In: Erftstadt City Yearbook 2002. Pages 106–109

- ↑ Rheinische Blätter for housing construction and building advice. Düsseldorf May 1921. pp. 126–129

- ↑ Dieter Gödderz, Glück auf! In: Liblar 1150-2000. The book on history. Liblar 1999. Pages 65-74

- ^ Website of the cultural administration of the city of Erftstadt , accessed on October 5, 2016

- ↑ Radio Erft News Archive: Music school, renovation / expansion in progress , accessed on October 5, 2016

- ↑ a b Peter Simons: Liblar, history and local history of the old imperial county in the Electorate of Cologne. 1956 pages 59–66

- ^ Frank Bartsch: Lechenich in the 19th century. Dissertation Bonn 2010. page 376

- ↑ Udo Müller, The new school on Heidebroich 1908-1930. In: Yearbook of the City of Erftstadt 2006, pages 135-139

- ↑ City Archives Erftstadt inventory A04-008

- ↑ Stadtarchiv Erftstadt inventory D 03/1 Collection Schloss Gracht_Erftstadt

- ↑ a b c Heidi and Cornelius Bormann: Home on the Erft. The rural Jews in the synagogue communities Gymnich, Friesheim and Lechenich. Erftstadt. 1993. Pages 374-376

- ↑ Ralf Othengrafen, First World War and occupation in the area of today's city of Erftstadt. In: Yearbook of the City of Erftstadt 2011, pages 6–23

- ↑ Volker Schüler and Manfred Coenen: The Donatus Briquette Factory 1890-1959. Documenta Berchemensis Historica. Volume 5. Self-published by Frechen 2004. Pages 99–102

- ↑ Gabriele Rünger, Who Voted the NSDAP? In: History in the Euskirchen district. 1987 pages 128 and 143

- ↑ Josef Grommes, Was Liblar brown? In: Liblar. 1150-2000. Liblar 1999. page 99

- ^ Dieter Heinzig: Information from the database of the NS Documentation Center of the City of Cologne and the memorial book of the Federal Archives

- ↑ Josef Bühl, the unfortunate January 13, 1945. In: Yearbook of the city of Erftstadt 1991. Pages 135-136

- ^ Parish archives St. Alban, parish chronicle

- ↑ Walter Kessler, The "daughter" has overtaken the "mother". In: Liblar. 1150-2000. Liblar 1999. Pages 43-47

- ↑ Sabine Böbe, The Church of St. Barbara in Erftstadt-Liblar. In: Yearbook of the City of Erftstadt 2009, pages 61–66

- ↑ Britta Havlicek: The book with seven seals, the windows in St. Barbara , Kölner Stadtanzeiger, Rhein-Erft, from December 18, 2009, p. 42 or online (accessed December 2009) ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Georg Grosser: Evangelical community life in the Cologne region , Cologne 1958, p. 58 f u. 105

- ↑ Dieter Heinzig, be reconciled with God. In: Liblar 1150-2000. The book on history. Liblar 1999. Pages 83-88

- ↑ Michael Folkers, briquette factories in Liblar. In the city of Erftstadt's yearbook 2002

- ^ Walter Buschmann , Norbert Gilson, Barbara Rinn: Brown coal mining in the Rhineland , ed. by the Landschaftsverband Rheinland and MBV-NRW , 2008, ISBN 978-3-88462-269-8 . (ubiquitous)

- ↑ City Archives Erftstadt A04-012

- ↑ Erftstadt City Archives A04-285

- ↑ City Archives Erftstadt A04-38

- ↑ Martin Bünermann: The communities of the first reorganization program in North Rhine-Westphalia . Deutscher Gemeindeverlag, Cologne 1970, p. 86 .

- ↑ Ralf Othengrafen, In the best years - 40 years of Erftstadt. Erftstadt yearbook 2010. Pages 5–18, information on page 8 with reference to: State Parliament NRW: VI. Election period, printed matter no.851, page 65

- ↑ a b c d e Walter Kessler, A start-up phase with surprises. In: Liblar 1150-2000. The book on history. Page 115

- ↑ Martin Bünermann, Heinz Köstering: The communities and districts after the municipal territorial reform in North Rhine-Westphalia . Deutscher Gemeindeverlag, Cologne 1975, ISBN 3-555-30092-X , p. 216 .

- ↑ Gisela Koschmider, Explosive Development. In: Liblar. 1150-2000. The book on history. Liblar 1999. Pages 127-132

- ↑ Alexander Kleinschrodt, Architecture of the 1950s and 1960s in Erftstadt. In: Erftstadt City Yearbook 2010. Pages 90–101

- ↑ Debus, Lutz: Schleyer kidnapping: How the saving note was lost. Die Tageszeitung , September 5, 2007, archived from the original on May 8, 2009 ; Retrieved May 8, 2009 .

- ↑ Alexander Kleinschrodt, Architecture and Urban Development of the Seventies and Eighties in Liblar and Lechenich. In: Yearbook of the City of Erftstadt 2011. Pages 104–115

- ↑ https://www.erftstadt.de/web/rathaus-in-erftstadt/rat-und-ausschuesse/ortsbuergermeister

- ↑ https://www.erftstadt.de/web/infos-zu-erftstadt/die-stadt-in-zahlen

- ↑ Kölner Stadt-Anzeiger - Rhein-Erft, December 23, 2013 p. 30

- ↑ Kölner Stadt-Anzeiger - Rhein-Erft, 25/26. January 2014 p. 44

- ↑ http://dpsg-liblar.de/

- ↑ Sabine Böbe, Lost Forever: The Liblarer station. In: Erftstadt City Yearbook 2002. Pages 115–118