Islamic expansion

In the following, the Islamic expansion refers to the conquests of the Arabs from the mid-630s and the accompanying expansion of Islam into the 8th century. With the beginning of Islamic expansion, the end of antiquity is often set.

In the 630s began the attack of the Arabs on the Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire and the New Persian Sassanid Empire , whereby both late ancient great powers were severely weakened by a long war against each other. The Eastern Romans lost 636 Palestine and Syria, 640/42 Egypt and up to 698 all of North Africa to the Arabs. While the Eastern Romans were able to hold a residual empire with a focus on Asia Minor and the Balkans, the Sassanid Empire went under in 651. In the decades that followed, the Arabs also attacked at sea. At the beginning of the 8th century they conquered the Visigoth Empire on the Iberian Peninsula and penetrated into Central Asia in the east in front.

Several cities often surrendered without a fight or after negotiations to the new masters. Christians , Zoroastrians and Jews were allowed to keep their faith as “ people of the book ”, but had to pay special taxes and accept restrictions on the practice of faith. The Islamization of the conquered areas took place at different speeds and proceeded rather slowly at first; 300 years after the military conquest, Muslims did not constitute the majority in many parts of the empire.

The Arab advance was finally stopped in the east by the Byzantines, while the Arabs in the west only made small advances into the Frankish Empire . This marked the beginning of the continued division of Europe and the Mediterranean into an Islamic and a Christian part in the early Middle Ages , which in turn split into a Latin West and a Byzantium-dominated Greek East .

initial situation

With the death of the Prophet Mohammed in 632 AD, the Islamic sphere of power extended to the Arabian Peninsula , the peripheral areas of which were largely under the control of the Byzantine Empire (Ostrom) and the Sassanid Empire .

For a long time, these two great powers of late antiquity had largely relied on Arab tribes to defend their borders. But the Sassanid great king Chosrau II had already destroyed the empire of the Lachmids , whose capital Hira was in what is now southern Iraq, around 602. Since the 5th century, Ostrom relied in many cases on the partly Christian Arab Ghassanids who ruled south of Damascus .

When Muhammad died, there was a movement of apostasy ( ridda ) among the Muslim Arabs , as many tribes believed that they were owed only to the Prophet himself. The first caliph Abū Bakr decided to continue to hold on to a not only religious but also political claim to leadership, and militarily subjugated the renegades; at the same time they were on the lookout for new, common enemies. The Arabs had carried out raids and raids long before. Religious, economic and domestic political motives that drove the Arabs came together for the following campaigns of conquest against the East and Persia (see also reasons for the fall of Persia and the eastern Roman territorial losses ).

The Arab conquest was favored not least by the unusual weakness of their opponents at the time: Both East and Persia were completely exhausted by a long war that lasted from 602/603 to 628/629 and consumed all resources, especially since both powers had previously entered the 6th century had repeatedly waged war against each other (see Roman-Persian Wars ). Both empires were completely fixated on each other and militarily not prepared for an attack by the Arabs. Shortly before the death of the emperor Herakleios (610 to 641), who had defeated the Sassanids with difficulty and thus saved the empire once more, the main phase of the Arab-Islamic expansion entered the main phase.

Islamic expansion

The Arab conquest of the Roman Orient

Beginning of the Arab attacks

An Islamic-Arab army had invaded Palestine as early as 629 , but was defeated by Eastern Roman troops near Muta in September. Since it seemed to be a rather minor advance, it did not attract any particular attention among the Eastern Romans. In fact, the emperor Herakleios and his advisors do not initially seem to have adequately assessed the danger. At the end of 633 / beginning of 634, however, an Arab army advanced to Palestine and Syria (see also Islamic Conquest of the Levant ). Herakleios delegated the defense (as before) to some of his generals and initially seems to have played for time to get more information about the attackers and the new faith; possibly his possibly worsened state of health also played a role.

The following events can be reconstructed from the sometimes quite extensive, but often problematic Islamic historiography (the relevant surviving works were not written until the 9th century) and individual Christian sources, although the early phase of expansion is poorly documented as well as the exact chronology, numbers and other detailed questions are often rather uncertain and in recent research it is also controversial whether one can speak of Islam as a separate religion at this early time. In February 634, the Arab units defeated the East Romans near Gaza, but they held out until late summer 637. In 634 the East Romans suffered two more defeats at Dathin and Ajnadayn, so that the Arab associations were able to penetrate relatively deep into Palestine and further into Syria. In 635 the Arabs conquered Damascus ; an often assumed siege is questionable, but in this connection there was a contractual handover regulation. The surrender treaty of the city of Damascus was to be given a model character; At least later regulations provided: The non-Muslim population should pay a poll tax ( jizya ), but was exempt from Islamic taxes, zakat and sadaqa . In addition, Christians and Jews were granted the restricted exercise of their religion.

Yarmuk and the conquest of Syria

The East Romans did not remain idle and organized a counter-offensive. In August 636, the Arabs were therefore forced to briefly evacuate Damascus and Homs (ancient Emesa). In August 636 the Battle of Yarmuk took place in what is now Jordan . The Muslim army was led by two eminent commanders: Chālid ibn al-Walīd and Abū ʿUbaida ibn al-Jarrāh . The details of the following events are difficult to reconstruct. The Eastern Roman troops - perhaps 40,000 men, but possibly significantly fewer - under the command of the Armenian General Vahan were initially in the majority, but exhausted from the march. Before the actual battle broke out, 636 smaller skirmishes had probably taken place since July. Apparently there was now a rift between Patricius Theodorus and Vahan, who was then proclaimed emperor by the Armenian soldiers in the army. At this moment of confusion, the Muslims attacked, and although the surprised Eastern Romans were still trying to defend themselves, they were decisively defeated after a fierce battle after the Arabs cut their route of retreat.

The fate of Syria and Palestine, which had previously been determined by Christian-Roman principles, was in fact sealed, although the Eastern Romans did not simply stop the fighting. Attempts were made to secure at least northern Syria and Roman Mesopotamia , but this failed. The imperial governor of northern Mesopotamia realized that he did not have enough troops for defense and was able to negotiate a tribute peace with the Arabs first; but he was deposed due to an intrigue by Herakleios, so that the Muslims attacked again in 639 and were able to take the area against little resistance.

Emperor Herakleios, who only a few years earlier had struggled to ward off the Persians, saw his life's work collapse and left Antioch before this city also fell to the Arabs. The imperial armies withdrew to Asia Minor. Some of the cities of Syria resisted independently, but in the end they all fell to the conquerors. In 638 at the latest, the isolated Jerusalem capitulated on favorable terms, while the important port city of Caesarea Maritima was able to hold out until 640/41 thanks to the imperial fleet; After the conquest, the remaining imperial troops stationed there (allegedly 7,000 men) were apparently massacred by the Arabs.

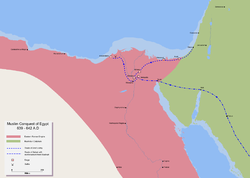

The conquest of Egypt

The Arabs no longer stood in the way of a Roman field army, so they advanced into Egypt , the breadbasket of Eastern Europe (see also the Arab conquest of Egypt ). The Arabs seem to have bypassed some fortified places, but the sources for the Arab conquest of Egypt are comparatively poor. The Arab advance, the first victim of which was Pelusium , probably began at the end of 639 , before the Arabs advanced into the actual Nile valley. The main target was the strategically important fortress of Babylon (now part of Cairo). In July 640 the Arabs destroyed an imperial army in the battle of Heliopolis , which had been commanded by the governor Theodoros. Babylon itself did not fall until April 641.

In the summer of 641, Cyrus, the former patriarch of Alexandria , was sent to the Arabs to negotiate a treaty. He was able to reach an agreement with the Arab commander in front of Babylon, according to which the Eastern Romans paid tributes and the Arabs in return promised to cease fighting in Egypt for eleven months and to allow the Eastern Romans to withdraw from Alexandria. Alexandria, the cosmopolitan city of Hellenism , finally fell into Arab hands in September 642; an imperial counter-offensive failed. After the organized military resistance of the imperial troops was broken, most of the civilian population in Syria and Egypt came to terms with the Arabs - perhaps all the more so since the Christians there were mostly " Miaphysites " and were in constant dispute with the " Orthodox " emperors had found. The extent to which disputes within the Christian church contributed to the success of the Arabs is now again very controversial in research. Of greater importance is the fact that Syria and Egypt had previously been Sassanid for years and had only recently become Eastern Roman again; the imperial administration had hardly been able to gain a foothold there when the Muslims attacked. Loyalty to Constantinople seems to have felt at best from the Hellenized elite. This made it easy for the Arabs as soon as the emperor's regular army was defeated. However, in the 8th century there were several uprisings of the Christian Copts against the Muslim rulers.

In the south, the Arabs advanced into ancient Nubia , into the Christian kingdoms of Nobatia and Makuria , where however the native defenders offered them bitter resistance and the Arab advance had to be broken off. The relationship between the Christian Nubian kingdoms and Egypt was then regulated in a contract ( Baqt ) in 652 , which also allowed the mutual exchange of goods.

Further Arab forays into Eastern Roman territory

In the Caucasus , the Arabs were also keen to gain ground. Christian Armenia was repeatedly attacked by Arab troops and submitted to Arab rule in 652/53 for favorable conditions, for which Theodoros Rštuni was sharply criticized in Armenian sources. In 655, however, the Arab advance in the Caucasus was stopped by the Khazars , who attacked an Arab force near Derbent , with the Arabs having to withdraw quickly.

In Asia Minor , the Taurus mountain range prevented a rapid advance; this saved the hull of the empire from doom. The East Romans used quite successfully a scorched earth tactics , decentralized defense and evaded a renewed big battle so that Asia Minor of them despite frequent Arab raids ( raids could be kept) ultimately. The Eastern Romans thus proved that they could react flexibly to military challenges if necessary. The multi-year internal Arab civil war from 656 onwards also gave them a decisive respite, with Muʿāwiya I concluding a limited armistice in 659. The Eastern Romans, whose resistance had almost been broken after the Battle of Phoinix in 655, were able to use this phase to reorganize their defense (see topic order ). Konstans II , the grandson of Herakleios, was able to stabilize the Eastern Roman position in the Caucasus and then, after a campaign against the Lombards in Italy, moved the imperial residence to Sicily for a few years in order to prepare a counter-attack, which however did not take place. Two large-scale Arab attacks on the capital Constantinople were then repulsed (see below); but the Eastern Roman forces, which were exhausted after the long Persian War, were no longer sufficient for a major counter-offensive.

In North Africa, the Arabs fought their way into what is now Morocco . Shortly after the conquest of Egypt, they made forays into the region of what is now Libya , where Tripoli fell to them in 643 . An Eastern Roman counter- attack in 647 by the former exarch of Carthage , Gregory , who had risen against Emperor Konstans II , failed and cost him his life. In 670 the Arabs finally advanced to Africa (from which the Arabic name Ifrīqiya is derived). Eastern Roman Carthage was able to hold out until 697/698, especially since the Berbers first fought the Arabs, just as they had fought the Romans before. The effective resistance against the Arabs in North Africa was broken, but later Berber uprisings continued, for example in 740.

Consequences of the Arab expansion

East or Byzantium lost two thirds of its territory and its tax revenues as well as more than half of the population with the Near Eastern possessions. The loss of Egypt in particular was painful due to its enormous economic power and the very high tax revenue. In addition, the Egyptian grain was of great importance for Constantinople. However, the development during the Persian War, which ended in 628, during which Egypt and Syria had been occupied by the Persians for years, shows that Byzantium was basically able to survive even without the strength of the oriental provinces.

The Arab raids in Asia Minor led to the demise of most of the poleis , which have now been abandoned or replaced by small, fortified settlements - such a fortified village was called Kastron . Numerous refugees poured into the remaining Eastern Roman areas and thus strengthened the empire in the long term, which in the 7th century lost its Latin character in considerable parts and was now also largely graced in the state sector (culturally Eastern Rome was already predominantly Greek). Byzantium took a long time to recover and return to a (limited) offensive, although some Byzantine counterattacks were still taking place in the 670s. Inside, as a reaction to the foreign policy threat, military districts, the so-called themes, were set up in the 7th century . This led to a stabilization of the situation, but the loss of North African territories as well as large parts of Syria and Palestine remained permanent; it sealed the end of the late antique phase of the empire, which subsequently went through massive administrative, military and structural changes. The old senatorial aristocracy almost completely disappeared and with it the ancient way of life and most of the classical education. It was replaced by a new elite of military climbers. It is no coincidence that the empire stabilized under the emperors of the Syrian dynasty , who were again successful militarily.

The situation for the Christian population in the conquered areas must be assessed in different ways. Despite the generally tolerant attitude of the Arab conquerors, several sources report that these conquests did not take place without acts of violence against the population. The Egyptian Christian Johannes von Nikiu reports in his chronicle, probably written around 660, of attacks by the Arabs during the conquest of the Nile land, although other sources convey a more positive picture. The Arab conquests in general evidently did not proceed without destruction and plundering as well as (as the example of Caesarea mentioned above) at least individual atrocities. The Christians, who were still in the majority for a long time, were basically able to exercise their faith to a limited extent, but already in the late 7th / early 8th century there were increased repressive measures and (state-sponsored) attacks on non-Muslims ( see below ).

The Arab conquest of the Sassanid Persian Empire

At about the same time as the invasion of the Roman possessions, the conquest of the Sassanid Empire began , which, alongside the Roman Empire, had been the most important power in the region for over 400 years. The situation for Persia, where Zoroastrianism dominated, but Christianity also played a not insignificant role, was strategically unfavorable at this point in time. The buffer that the Arab Lachmids had formed as Persian vassals had already been removed by the time of King Chosrau II .

In particular, the power struggles that began after 628 and the civil wars after the war against Herakleios weakened the Persian resistance to the Muslim Arabs. In the four years between 628 and 632, eight rulers and two women ruled (sometimes at the same time in different parts of the empire). Only at the end of 632 did a relative inner calm return; When the Arab attacks began, the new, still very young, Great King Yazdegerd III organized. the defence. In fact, a first Arab attack in 634 was successfully repulsed in the Battle of the Bridge ; but renewed internal turmoil prevented the Sassanids from taking advantage of this victory. The Sassanid spahbedh ("imperial general ") Rostam Farrochzād , who commanded the western border troops, had to move with his troops to Ctesiphon after the victory in order to suppress a revolt there. The Arabs used this to regroup.

Nevertheless, the Persians opposed the further advance of the Arabs, especially since the Sassanid army was still strong enough to fight despite the long war against Eastern Stream. It is quite unclear whether the heavily armored Sassanid cavalry was fundamentally inferior to the light, fast-operating Arab cavalry, as is often assumed. In January 638 (not 636 or 637) the second major battle took place near Kadesia in southern Iraq, but little is known about it. Rostam Farrochzād was killed this time after a bitter struggle, and the Arabs fell into the hands of rich Mesopotamia, including the main Sassanid residence, Ctesiphon . The rapid collapse of the Sassanid border defense in Mesopotamia was perhaps also due to the reforms that Chosrau I had carried out in the 6th century: Since then, only one border army has ever faced possible attackers, while no further troops were staggered in the depths. In addition, a number of aristocrats do not appear to have participated in the fight against the invaders. The Arabs then advanced into Khuzestan .

The further defensive measures of the Persians were initially uncoordinated, but later the resistance increased again. Yazdegerd III. withdrew to the Iranian highlands, where the king could mobilize new resources. Especially in the Persian heartland, the Iranian plateau east of the Tigris , the Arabs made slow progress at first. Indeed, the Arabs seem to have considered whether it would make sense to move further, as the risks were recognized. But in 642 Yazdegerd III. launched a major counter-offensive, and so the Arabs also assembled a strong army and attacked swiftly to forestall the Sassanid attack. A decisive battle broke out near Nehawend (south of today's Hamadan ) . The Persians were probably in the majority, but numbers of 150,000 or more can be attributed to the efforts of Arab chroniclers to make the victory appear even more glorious. Concrete information is difficult to make: It seems plausible that the Arabs led over 30,000 men into battle; the Sassanid army is likely to have been slightly superior in numbers. The closest source in time, the Armenian chronicler Sebeos , speaks of 40,000 Arabs and 60,000 Sassanids. At first the Persians seemed to be victorious, but then they were evidently lured out of their position by a ruse by the Arabs, who themselves suffered heavy losses (it was probably pretended to have received reinforcements) and after a hard fight they were cut down. The king's soldiers were defeated, and the Iranian high plateau was open to the invaders.

Organized resistance did not collapse immediately, although several Persian nobles apparently came to terms with the invaders. The time of turmoil between 628 and 632 had damaged the Sassanid rulership, because Yazdegerd was not recognized unchallenged throughout the empire, as can be proven by coinage, and was only ever able to gain regional authority; Ultimately, it was no longer a question of centralized royal power, but more of a travel royalty. This made the coordinated defense against the Arabs much more difficult, while regional nobles (see also Dehqan ) gained power and used them to damage the kingship. In the final phase, some units of the Sassanid cavalry even defected to the Arabs: They were settled in the south of what is now Iraq and, as Asāwira, played a not unimportant role militarily in the early caliphate for some time ; they were also not obliged to convert to Islam.

In the following years, however, there were repeated uprisings among the population, with the Arabs being sometimes referred to as "devils" . Furthermore, it took the Arabs some time to conquer various fortified cities, the garrisons of which often did not simply give up ( Istachr and Jur still held out in 650). While the Arabs were advancing into the Persian heartland, they were simultaneously making systematic advances on the Iranian coast. In some regions, however, the Persians were to resist bitterly for decades. In fact, it took the Arabs longer to conquer the Sassanid Empire than it did to conquer Syria and Egypt from the Eastern Romans. The conquest of Iran was associated with considerable losses. This seems to have strengthened the Arabs in their determination to achieve complete submission to the Sassanids. When they took Istachr, they even massacred the people who had been loyal to Yazdegerd; allegedly 40,000 people are said to have been killed.

Yazdegerd III, who tried in vain for a coordinated resistance after 642, finally withdrew to the extreme northeast of the empire to Merw . There he was killed by a subordinate in 651 - centuries later his descendants were nicknamed "regicide" because of this act. Attempts by his eldest son Peroz to regain power with Chinese help failed; he died in the Far East at the court of the Tang Emperors .

The Sassanid Empire and the last empire-building of the ancient Near East disappeared as from the stage of world history, even if the Sassanid culture a strong echo in the Caliphate of the Abbasids took place and thus survived the sinking state. Only around 900 did the Muslims in Iran form the majority; Significant Zoroastrian minorities are attested in the 11th century, and Zoroastrian fires were still burning in southeastern Iran in the 13th century. Significantly, in contrast to most of the other peoples conquered by the Arabs, the Persians also retained their language, and several powerful noble families who had come to an understanding with the Arabs in time retained their position for centuries.

Central Asia and Sindh

In the east, the Arabs invaded Central Asia around 700 and later on to the borders of China and India . The late ancient Central Asia was a politically fragmented area with local rulers and (semi) nomadic steppe peoples . In Transoxania they gradually conquered the Turkish possessions, combined with their slow and momentous Islamization. The Arab subjugation of the city-states of Sogdia also began. Paykand fell in 706, Bukhara in 709 and Samarkand in 712 (where the Turkish city lord Ghurak was confirmed in office, but who later rose against the Arabs). Here, however, the Arabs were stubbornly resisted. A Sogdian revolt in 722 failed, with Dēwāštič , lord of panjakent was executed by the Arabs.

In the course of the fighting with the Turkish tribal group of the Türgesch (who assumed the political legacy of the Western Turks and even allied themselves with the powerful Tibetan Empire) under Suluk , other tribal groups and the Sogdian city-states, the Arabs also suffered several severe setbacks, which led to the further Arab advance was severely hampered. The Arabs suffered a heavy defeat in 724, which Tabari called "the day of thirst" and which triggered an uprising against the Arabs in Transoxania, so that the Arabs temporarily gave up several cities and could only hold Samarkand; In 731 a Muslim army barely escaped annihilation. Only the death of Suluk in 738 seems to have ended the organized resistance. Nevertheless, regional rulers (such as in the area of today's Kabul , see Turk-Shahi and Hindu-Shahi ) fought the Arab invaders for several decades.

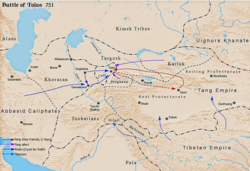

Not only the Arabs, but also the Chinese Tang dynasty pursued their own interests in Central Asia. Suluk was even defeated by a Chinese army in 736 before succumbing to the Arabs in 737 and murdered a year later. After the organized resistance against the Arabs had virtually died down, an open confrontation broke out between the caliphate and the Chinese. In the summer of 751, the Arabs defeated a Chinese army in the Battle of the Talas . The importance of the battle has been exaggerated. However, the Chinese influence in Central Asia was ultimately pushed back in favor of the Arab-Islamic one.

Around 710 the Arabs also made their first forays into Sindh , for which the sources are very poor. However, the Arab defeat against the local rulers of the Rashtrakutadynasty , whose armies were quite a match for the Arab troops in the Battle of Rajasthan, prevented further expansion into West and Central India .

The Arab conquests in Europe

The Arabs armed themselves under the caliph Umar Ibn al-Chattab as a sea power and hit the lifeblood of Byzantium. In 649 they made an advance into Cyprus (the proceeds of which were contractually divided between Byzantium and the Caliphate in 688). In 654 the Arabs sacked Rhodes , in 655 they were able to defeat a Byzantine fleet for the first time in the Battle of Phoinix , although the Byzantines still had a considerable fleet at their disposal.

In 717/18 they besieged Constantinople without being able to capture; Whether there was also a real siege from 674 to 678 is, however, controversial in recent research. The stopping of the Arab expansion by the extremely capable Byzantine Emperor Leon III. probably the more important rank than the later, often overestimated victory of the Franks (see below). Leon was also able to defeat the Arabs in Asia Minor in 740. With the Byzantine successes, the Arab-Islamic advance in Asia Minor came to an end, as the resources were also by far overused. Fighting between the Arabs and the Khazars in the Caucasus was rather unfavorable for the Arabs (in 722 an Arab association was formed and destroyed, in 726 the Arab governor of Armenia was killed), so that both sides finally came to an understanding.

After conquering the North African coastal areas, Muslim troops (mainly Berbers) landed under Tāriq ibn Ziyād near Gibraltar (Mount des Tariq) in 711 . The Visigoths were defeated in July 711 in the Battle of the Río Guadalete . The Iberian Peninsula was conquered from 711 to 719. In 720 Narbonne fell to the Muslim troops (the area around Narbonne was held by them until 759), who repeatedly advanced into Franconian territory. An advance into the Franconian Empire in 732 was stopped by Charles Martell in the battle of Tours and Poitiers , but the importance of the battle has been overestimated for a long time, especially since it was probably a limited raid. Subsequently, after the end of the Umayyad caliphate, an independent Umayyad empire emerged in Al-Andalus , the Emirate of Córdoba , which later became the Caliphate of Córdoba .

The first major and decisive phase of the Arab-Islamic expansion thus lost momentum, especially since the resources of the caliphate were limited. In the 9th century, however, the Arabs repeatedly took action against Byzantium. In 827 the Arabs landed in Sicily and took control of the island around 900 (fall of Syracuse in 878, fall of Taorminas in 902). In the eastern Mediterranean the Arabs were able to operate successfully for some time, partly in the form of open piracy (e.g. Leon of Tripoli ), although the Byzantine fleet was by no means eliminated. In 823/28 the Arabs conquered Crete , which was a heavy blow for the Byzantines. In the 10th century, however, the successful Byzantine counter-offensives followed: In 961, Crete was recaptured, and in 965, Cyprus fell to the Byzantines, who also briefly advanced into Syria. From the 12th century onwards, the Islamic powers were weakened by the Crusades . In the west, the Islamic Emirates were pushed back bit by bit from the High Middle Ages : on the Iberian Peninsula by the Reconquista of the Christian kings, which came to an end in 1492, and in the 11th century by the Norman conquest of Sicily.

Administrative measures by the Arabs in the conquered areas

In Syria, the Arabs divided the country into four administrative regions based on the Byzantine model. Former administrative officials were also taken over, with the result that Greek (in the former Eastern Roman areas) and Persian (in the former Sassanid Empire) continued to be used as the administrative language. The Greek administration was regulated from Damascus, the Persian-speaking one from Kufa ; It was not until the reign of Abd al-Malik that both languages were replaced and pushed back in the administration by Arabic. However, this process evidently proceeded quite slowly, because in the early 8th century the official correspondence of the Egyptian governor Korrah ben Sharik was also written in Greek, as preserved papyri show.

Furthermore, the Arabs initially used the Byzantine and Sassanid coins in circulation, which were often only minted slightly differently until they themselves minted new coins that no longer had any pictures. The Arabs also founded new cities (Kufa, Basra , Fustat , Kairouan , Fès ), which initially served as military camps but eventually took on the function of administrative and cultural centers. So the Arab administration for Egypt was initially organized from Fustat, about which preserved papyri provide interesting insights.

Apparently the Arabs made relatively little changes to the existing administrative systems, which had already worked effectively. At first, the new state was built relatively loosely, with the governors largely free. It was only Muawiya I , the actual organizer of the caliphate, who created a tighter central administration. In the former Eastern Roman / Byzantine areas, there were initially still predominantly Christians, such as Sarjun ibn Mansur , who was responsible for finances under Muawiya. The numerous Christian officials were only ousted from their posts over time, as they were indispensable for a long time. The Islamization or Arabization of the conquered areas dragged on over a longer period of time and made slow progress at first. This was due to the fact that it was not until the Abbasid period that the opportunities for advancement for non-Arab Muslims increased.

Position of other religions under Muslim rule

According to the interpretation of Islamic law at the time , the Muslim rulers were obliged to tolerate the presence of other book religions - that is, Christians, Jews and in Persia also the Zoroastrians identified with the Sabaeans mentioned in the Koran in sura 22:17 - unlike polytheists . They were allowed to keep their faith, live it out in small communities and not be forced to give it up.

The Christian churches in Egypt, Syria and Mesopotamia retained their importance for a long time and the majority of the population under Arab rule remained Christian for a long time. Some Christians initially continued to work in the administration of the caliphate, others worked as scholars at the court of the caliph, such as B. Theophilos of Edessa in the middle of the 8th century . After the conquest, the Arab rule did not initially encounter any significant resistance, especially since the Arabs used the old administrative system and initially changed relatively little.

In the Koran a strict distinction is made between Muslims and those of other faiths, so that while Christians and Jews are granted partial faith, they are also subject to partial unbelief and the claim to absoluteness of both religions is disputed, since Islam is the only true faith. The Zoroastrians represented a special case and, strictly speaking, did not belong to any revealed religion. After some hesitation, however, Muslim religious scholars included them, put them on an equal footing with the Sabaeans and thus no longer regarded them as idolaters who were to be forcibly converted. Tradition also shows that Muslim authors (later mainly those of Persian descent) had a great deal of interest in Zoroastrianism and that Iranian elements influenced some of the early Arabic-Islamic literature. However, Zoroastrians were later persecuted by Muslim rulers.

Furthermore, the Mandaeans were identified with the Sabeans . Later, in order to obtain protection and rights under Muslim rule, the Sabians also counted themselves among the Sabeans named in the Koran . As a result, various mix-ups and amalgamations of the various religions identified with the Sabaeans in law and exegesis occurred among Islamic authorities and exegetes .

Those of other faiths had to pay a special poll tax ( jizya ), were allowed to keep their faith and practice it in their own communities, whose internal affairs they had to regulate themselves. Nevertheless, they were forbidden to build new synagogues and churches in cities and larger towns and they were not allowed to carry weapons, even though under the first caliphs Christian Arabs were conscripted as soldiers and those of different faiths were also obliged to perform military auxiliary services. Restrictions were also made in inheritance law and in some cases special clothing regulations were issued. These measures clearly emphasized that the non-Muslim majority population was by no means legally equal to the Muslims. This status is known as Dhimma , which was granted to the Zoroastrians (as well as the Sabians, who, however, played a more local role) in addition to Jews and Christians. According to this, it was a matter of “protected persons” whose religion enjoys a certain freedom, but is fundamentally subject to Islam, whose followers are not recognized as full believers and against whom the Koran is sometimes also polemicized. Here, not least, the recognition of the prophetic mission of Muhammad and the Koranic revelation were at the center of Muslim considerations, since these aspects did not occur in Judaism and Christianity. Many provisions go back to the phase of Islamic history when the Muslim community was constituted and was in a struggle for self-assertion.

Basically, the behavior of the new Muslim masters towards the numerically far superior Christian majority population was often shaped by expediency: Christians were used in the administration because they were familiar with it, and the protection treaties were used to bring the Christian majority population under a certain control, since one was dependent on their cooperation; The initially exercised tolerance towards non-Muslims was primarily based on practical considerations. In the early days after the conquest, coexistence was initially without major difficulties. However, this changed in the following period, when there were attacks and restrictive measures against Christians, as early as the end of the 7th century. This was related to the respective religious policy of the ruling caliph. When Arabic became the official language in the administration in 699, thus replacing Greek or Middle Persian, this was apparently also connected with the ban on employing non-Muslims in the administration; however, this was probably not put into practice consistently because they were indispensable for many posts for a long time. Christians (and Zoroastrians in the former Persian Empire) were therefore no longer allowed to hold high government posts and were excluded from a significant part of society. John of Damascus , the son of Sarjun ibn Mansur , retired to a monastery around 700, but Christian officials are still well documented in the period that followed, before this practice was completely broken.

Social life was increasingly geared towards the new Islamic faith and the spheres of life of Muslims and non-Muslims should apparently be deliberately separated from one another. This can be seen, among other things, from the mentioned new coinage of this time (since approx. 697), which were provided without pictures but with Koran suras (Sura 112). Religious acts of worship by non-Muslims, which were initially hardly hindered, were still more restricted in the late Umayyad period; in addition, there were actions that demonstrated a certain feeling of superiority on the part of the Muslim rulers over non-Muslims. In the Caliphate, for example, the public presentation of crosses and Christian prayers in public were forbidden and individual churches were possibly destroyed (the sources for the last point are not clear). What is certain is that restrictive measures and regulations, especially with regard to Christians, increased. The Muslim rulers now increasingly intervened in internal Christian affairs and also confiscated churches; Since the 9th century, there have also been works by Muslim authors who polemicized against other book religions.

The overall increasing pressure was not without its effects: In Egypt the Christian Copts revolted six times against Muslim rule between 725 and 773 alone, but the uprisings were suppressed. The attacks then increased noticeably in the 9th century when individual churches were looted and destroyed. The tax burden also increased. All in all, it can be said that (following restrictive measures as early as the late Umayyad period), since the early Abbasid period, when the Islamic community in the conquered areas slowly began to consolidate, there has been government-led control of Christians in everyday life. They were allowed to keep their faith, but there were social humiliations and phases of oppression with targeted persecution, with political and religious motives mixed with one another; however, there were also phases in which some measures were at least temporarily relaxed. Around 900, administrative posts were again briefly filled with Christians and Jews, but an edict issued in 908 again prohibited the employment of non-Muslims in public functions: Christians and Jews were therefore only allowed as doctors (Christian doctors, for example, had a good reputation at the Caliph's court enjoyed) or bankers are employed, and special dress codes have been issued for both groups. The chronicle of Pseudo-Dionysius of Tell Mahre is an important source of repression . The earliest Christian report on the relationship between Christians and Muslims comes from the Catholicos Ischo-Jab III.

The number of converts in the conquered areas initially remained low, as the associated advantages were limited in the first few decades: Until the Abbasids came to power, only men who could prove an Arab origin could pursue a career regardless of religion. Christianity and Zoroastrianism were only gradually pushed back; Probably only around the year 1000 did the majority of the population of Egypt and Iraq speak Arabic, while in Persia their own cultural identity could be preserved more strongly. Apparently, some Muslim theologians and legal scholars also believed that discriminatory measures against non-Muslims would encourage conversion to Islam; social pressure was therefore arguably an important factor in the “Islamization” of the conquered societies, where the Christian majority population became a minority over time.

Reasons for the fall of Persia and for the eastern Roman loss of territory

The reasons for the success of the Arab-Islamic conquests in the 7th and early 8th centuries - that is, over a longer period of time and not without losing battles for the Arabs - are still being discussed in research. There can be no general explanation for this, rather the success (there are parallels with the Alexanderzug and the Mongolian conquests ) was favored by a multitude of factors.

Ostrom (Byzantium) and Persia were completely exhausted by the centuries-long Roman-Persian wars . Since 540 there had only been a good 20 years of peace between the two powers, in the last war the Sassanids brought the Romans to the brink of extinction. The Eastern Roman army had been demobilized for financial reasons after the long wars against the Persians and needed a long lead time to be reactivated. In the meantime, the Sassanid Empire was weakened less by the battles with the Romans than by the civil wars that had raged since 628; the great Persian victory in the battle of the bridge in 634 illustrates that one would have been a match for the Muslims militarily if Yazdegerd III. would have succeeded in pacifying his empire inside. Instead, however, many Persian magnates defected to the attackers.

The consequences of the long war with Persia played a greater role for Ostrom than for the Sassanids. Thus the oriental provinces of Estrom were only reintegrated into the empire a few years before the Arab attack; the distant headquarters in Constantinople actually only appeared through merciless tax collectors. For religious reasons, too, the orthodox imperial government was not particularly popular in Syria and Egypt, as miaphysitism was predominant here . Even so, the Egyptians and Syrians often enough participated in the resistance against the invaders. In this context, the dissatisfaction in Egypt and Syria with the religious policy of the emperors was probably often taken over in an undifferentiated manner by older researchers; In any case, in recent research this thesis is again very controversial.

Overall, however, no such religious energy was expected in Constantinople or in Ctesiphon, let alone such an invasion, even if there had been some signs beforehand. Religion had already played an important role in the last Roman-Persian war, when Emperor Herakleios equated the defense of the Persians with a defensive struggle against Christianity and, from 622, also accepted Arab foederati into his army. Arab associations had previously served both East and Persia as auxiliary troops and had adequate military knowledge.

In addition, the Arabs allowed the subject population to practice their religion (albeit limited) in return for a poll tax, although according to some sources there were restrictive measures and attacks against non-Muslims as early as the 7th century ( see above ), which had been against Muslims from the beginning in the caliphate were legally disadvantaged. The population was Islamized only gradually, certainly also because otherwise there were in fact hardly any opportunities for advancement, their legal position ( dhimma ) was generally precarious and restrictive measures against non-Muslims favored conversion. Initially, the conquerors were not allowed to take over any land as private property, but this later changed.

However, there was rich booty, which was certainly a great incentive for many tribes on these campaigns. In any case, economic considerations (such as the trade interests of the Quraish ) seem to have played a more important role than often assumed religious considerations. Furthermore, it is documented in the sources that associations of militarily well-trained Christian Arabs defected in part to the Muslim conquerors; not for religious reasons, but because the previous payments from Eastern Europe and Persia had largely collapsed. Religious motives should therefore not be overemphasized. Only later sources report attempts to convert the population of the subject areas to Islam; a later development is likely to be projected onto the early days. When many Christians, Jews and Zoroastrians finally converted, they brought their ideas and practices into the new religion.

Many elements of the previous administration and culture were taken over by the Arabs. The Arab conquerors also profited considerably from the already existing higher cultural development in the former Eastern Roman areas and in Persia. In the latest research, some take the position that the early Islamic expansion was less an invasion than an insurrection, since most Arabs had previously been under direct or indirect Roman and Persian rule and have now undertaken to to forcibly appropriate the power and wealth of their previous masters. For this reason, they initially had no reason to change anything in the existing structures. For example, Greek remained the official language in the conquered Eastern Roman territories until the end of the 7th century, and the Sassanid tax system was retained in Persia. In the first few decades, Sassanid coins continued to be minted. This, in turn, should have made it easier for the inhabitants of the conquered areas to accept the new masters, who were initially only a tiny minority.

Sources

The sources of the Arab campaigns of conquest against East Stream / Byzantium and Persia are very problematic, as is the reconstruction based on them. For a long time, the basic features were largely followed as far as possible from the detailed Islamic-Arabic sources. In more recent research, however, most researchers are now taking a more critical stance towards the Islamic texts that were written several decades or centuries later, some of which are incorrect or falsified, and the attempts at reconstruction based on them. Even those historians who continue to refer to the extensive Arabic tradition of the campaigns ( futūh ) and who are forced to use the difficult source situation meanwhile mostly see the problem of the source tradition and evaluate many statements more skeptically than was usual in older research. A very controversial extreme position is taken by researchers who question the entire course of events in early Islamic history, consider Islam to be an originally Christian heresy and the figure of the prophet Mohammed in some cases even a later invention (which has not been accepted in research) .

The sources on the Islamic side of the Arab campaigns that have been preserved (albeit with a clear time lag to the events described) include Baladhuri and Tabari, among others, in great detail, although their descriptions - such as chronology, figures and some content-related statements - are not always reliable are. From a Christian point of view, there are only scattered statements, some of which were written very close to the events and convey important information. These include, for example, the Armenian historical work of Pseudo- Sebeos (which is considered to be quite reliable in research), the problematic chronicle of John of Nikiu and various Syrian-Christian chronicles. Central Byzantine authors such as Theophanes were also able to fall back on some of the works that have now been lost. Of particular importance in this context is the lost Syrian chronicle of Theophilos of Edessa , which contained important and probably largely correct information. It was used (partly indirectly) by several Syrian authors and the Christian Arab Agapios of Hierapolis ; mediated by an intermediate source, it was then also used by Theophanes in the early 9th century. In pseudo-historical sources, Christian authors also processed the surprising assumption of power by the Arabs (e.g. Apocalypse of Pseudo-Methodius ).

In addition to the narrative sources, coins, inscriptions, papyri and buildings also play a role, although these only provide information about (but in some cases significant) individual aspects; however, the interpretation of these testimonies (such as the Arabic inscription in the Dome of the Rock ) is in part controversial.

literature

- Lutz Berger : The Origin of Islam. The first hundred years. CH Beck, Munich 2016, ISBN 978-3-406-69693-0 .

- Glen W. Bowersock : The Crucible of Islam. Harvard University Press, Cambridge (Mass) / London 2017, ISBN 978-0-674-05776-0 .

- Averil Cameron et al. (Ed.): The Byzantine and Early Islamic Near East. Volume 1ff. Darwin Press, Princeton NJ 1992ff., ISBN 0-87850-107-X .

- Fred M. Donner : Muhammad and the Believers. At the Origins of Islam. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA et al. 2010, ISBN 978-0-674-05097-6 .

- Fred M. Donner: The Early Islamic Conquests. Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ 1981, ISBN 0-691-05327-8 .

- John F. Haldon: The Empire That Would Not Die. The Paradox of Eastern Roman Survival, 640-740. Harvard University Press, Cambridge (Massachusetts) 2016.

- Douglas Haug: The Eastern Frontier. Limits of Empire in Late Antique and Early Medieval Central Asia. IB Tauris, London / New York 2019.

- James Howard-Johnston : Witnesses to a World Crisis. Historians and Histories of the Middle East in the Seventh Century. Oxford University Press, Oxford et al. 2010, ISBN 978-0-19-920859-3 .

- Robert G. Hoyland : In God's Path. The Arab Conquests and the Creation of an Islamic Empire. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2015.

- Robert G. Hoyland: The Identity of the Arabian Conquerors of the Seventh-Century Middle East. In: Al-ʿUṣūr al-Wusṭā 25, 2017, pp. 113–140.

- Robert G. Hoyland: Seeing Islam as Others Saw It. A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam . Darwin Press, Princeton NJ 1997.

- Andreas Kaplony: Constantinople and Damascus. Embassies and treaties between emperors and caliphs 639-750. Schwarz, Berlin 1996 ( Menadoc Library, University and State Library Saxony-Anhalt, Halle ).

- Walter E. Kaegi: Byzantium and the Early Islamic Conquests. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1992, ISBN 0-521-48455-3 .

- Walter E. Kaegi: Muslim Expansion and Byzantine Collapse in North Africa . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2010, ISBN 978-0-521-19677-2 .

- Walter E. Kaegi: Confronting Islam: emperors versus caliphs (641 – c. 850). In: Jonathan Shepard (Ed.): The Cambridge History of the Byzantine Empire. c. 500-1492. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge et al. 2008, ISBN 978-0-521-83231-1 , p. 365ff.

- Hugh Kennedy : The Great Arab Conquests. How the Spread of Islam changed the World we live in. Da Capo, Philadelphia PA 2007, ISBN 978-0-306-81585-0 .

- Hugh Kennedy: The Byzantine and Early Islamic Near East. Ashgate Variorum, Aldershot et al. 2006, ISBN 0-7546-5909-7 ( Variorum Collected Studies Series 860).

- Daniel G. König: assumption of power through multilingualism. The languages of the Arabic-Islamic expansion to the west. In: Historische Zeitschrift 308, 2019, p. 637 ff.

- Ralph-Johannes Lilie : The Byzantine reaction to the expansion of the Arabs. Studies on the structural change of the Byzantine state in the 7th and 8th centuries . Institute for Byzantine Studies and Modern Greek Philology at the University of Munich in 1976 (also dissertation at the University of Munich in 1975).

- Maged SA Mikhail: From Byzantine to Islamic Egypt. Religion, Identity and Politics after the Arab Conquest. IB Tauris, London / New York 2014.

- Michael G. Morony: Iraq after the Muslim Conquest. Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ 1984, ISBN 0-691-05395-2 ( Princeton studies on the Near East ).

- Albrecht Noth : Early Islam. In: Ulrich Haarmann (ed.): History of the Arab world. 3rd expanded edition. Beck, Munich 1994, pp. 11-100, ISBN 3-406-38113-8 .

- Petra M. Sijpesteijn: Shaping a Muslim State. The World of a Mid-Eighth-Century Egyptian Official. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2013.

- Thomas Sizgorich: “Do Prophets Come with a Sword?” Conquest, Empire and Historical Narrative in the Early Islamic World . In: American Historical Review 112, 2007, pp. 993-1015.

Web links

- Spahbed Rustam Farrukh-Hormazd and The Faith Making Battle of Qadisyyeh , Iran Chamber Society (English)

- Medieval Sourcebook: Accounts of The Arab Conquest of Egypt, 642 , excerpt from the source for the conquest of Alexandria

Remarks

- ↑ See Lutz Berger: The emergence of Islam. The first hundred years. Munich 2016, p. 112ff .; W. Montgomery Watt: Muhammad at Medina . Oxford 1962, pp. 78-151; Elias Shoufani: Al-Ridda and the Muslim Conquest of Arabia. Toronto 1973. pp. 10-48.

- ↑ Lutz Berger: The emergence of Islam. The first hundred years. Munich 2016, p. 136ff.

- ↑ James Howard-Johnston: The Last Great War of Antiquity. Oxford 2021.

- ↑ See for example Lutz Berger: The emergence of Islam. The first hundred years. Munich 2016, p. 71ff.

- ↑ On the Persian War and its consequences see Walter E. Kaegi: Heraclius. Cambridge 2003, p. 100ff.

- ↑ Haldon has presented a general and important overall account of the position of the Eastern Roman Empire in the 7th century: John Haldon: Byzantium in the Seventh Century. 2nd edition Cambridge 1997; on the situation of the empire see also Theresia Raum: Scenes of a struggle for survival. Actors and room for maneuver in the Roman Empire 610–630. Stuttgart 2021. For a summary of the initial situation at the start of expansion, see Robert G. Hoyland: In God's Path. The Arab Conquests and the Creation of an Islamic Empire. Oxford 2015, p. 8ff.

- ↑ It should be noted that this is a simplification: the attackers were not exclusively Arabs, nor were they exclusively followers of Muhammad; see Robert G. Hoyland: In God's Path. Oxford 2015, p. 5.

- ^ Walter E. Kaegi: Heraclius. Cambridge 2003, p. 231; Walter E. Kaegi: Byzantium and the Early Islamic Conquests. Cambridge 1992, pp. 71-74.

- ^ Walter E. Kaegi: Heraclius. Cambridge 2003, p. 233ff.

- ↑ See Walter E. Kaegi: Heraclius. Cambridge 2003, pp. 237f.

- ↑ For the following explanations see general: Lutz Berger: The emergence of Islam. The first hundred years. Munich 2016, pp. 141ff .; Fred Donner: Muhammad and the Believers. Cambridge MA et al. 2010, p. 106ff .; Fred Donner: The Early Islamic Conquests. Princeton 1981, pp. 91ff .; Robert G. Hoyland: In God's Path. Oxford 2015, p. 31ff .; Walter E. Kaegi: Byzantium and the Early Islamic Conquests. Cambridge 1992, pp. 66ff .; Hugh Kennedy: The Great Arab Conquests. Philadelphia 2007, pp. 66ff .; Ralph-Johannes Lilie: The Byzantine reaction to the expansion of the Arabs. Munich 1976, p. 40ff.

- ^ Robert G. Hoyland: In God's Path. Oxford 2015, p. 42; Walter E. Kaegi: Byzantium and the Early Islamic Conquests. Cambridge 1992, p. 67 and p. 88ff.

- ^ Walter E. Kaegi: Byzantium and the Early Islamic Conquests. Cambridge 1992, p. 67 and p. 88ff.

- ↑ In detail Jens Scheiner: The conquest of Damascus. Source-critical examination of the historiography in classical Islamic times . Leiden / Boston 2010.

- ^ Walter E. Kaegi: Byzantium and the Early Islamic Conquests. Cambridge 1992, p. 67.

- ^ Robert G. Hoyland: In God's Path. Oxford 2015, pp. 45f .; Walter E. Kaegi: Byzantium and the Early Islamic Conquests. Cambridge 1992, p. 112ff .; Hugh Kennedy: The Great Arab Conquests. Philadelphia 2007, pp. 83-85.

- ^ Robert G. Hoyland: In God's Path. Oxford 2015, p. 46.

- ↑ See Walter E. Kaegi: Byzantium and the Early Islamic Conquests. Cambridge 1992, p. 147ff.

- ^ Robert G. Hoyland: In God's Path. Oxford 2015, p. 48f.

- ↑ Lutz Berger: The emergence of Islam. The first hundred years. Munich 2016, p. 196ff .; Robert G. Hoyland: In God's Path. Oxford 2015, p. 68ff .; Hugh Kennedy: The Great Arab Conquests. Philadelphia 2007, pp. 139ff.

- ^ Hugh Kennedy: The Great Arab Conquests. Philadelphia 2007, p. 151.

- ^ Hugh Kennedy: The Great Arab Conquests. Philadelphia 2007, pp. 152f.

- ^ Robert G. Hoyland: In God's Path. Oxford 2015, pp. 74f.

- ^ Robert G. Hoyland: In God's Path. Oxford 2015, p. 76.

- ^ Robert G. Hoyland: In God's Path. Oxford 2015, pp. 76-78. For the history of this room, see Derek A. Welsby : The Medieval Kingdoms of Nubia. Pagans, Christians and Muslims on the Middle Nile. London 2002.

- ↑ See Robert G. Hoyland: In God's Path. Oxford 2015, pp. 89f.

- ^ Robert W. Thomson, James Howard-Johnston: The Armenian History Attributed to Sebeos. Liverpool 1999, Chapter 50, pp. 147-149.

- ↑ Cf. Ralph-Johannes Lilie: The Byzantine reaction to the expansion of the Arabs. Munich 1976, p. 97ff.

- ↑ Ralph-Johannes Lilie: The Byzantine reaction to the expansion of the Arabs. Munich 1976, p. 68f.

- ^ Walter E. Kaegi: Muslim Expansion and Byzantine Collapse in North Africa. Cambridge 2010; Hugh Kennedy: The Great Arab Conquests. Philadelphia 2007, pp. 200ff.

- ↑ On this transformation process see introductory John Haldon: Byzantium in the Seventh Century. 2nd edition Cambridge 1997.

- ↑ On these different reports see Hugh Kennedy: The Great Arab Conquests. Philadelphia 2007, p. 350ff.

- ↑ Current summary of the political history in Touraj Daryaee: Sasanian Iran 224-651 CE. Portrait of a Late Antique Empire. Costa Mesa (Calif.) 2008. Josef Wiesehöfer offers a good overview of the ending Sassanid Empire: The Late Sasanian Near East. In: Chase Robinson (Ed.): The New Cambridge History of Islam. Vol. 1. Cambridge 2010, pp. 98-152.

- ↑ On the conquest of the Sassanid Empire (with further literature) Lutz Berger: The emergence of Islam. The first hundred years. Munich 2016, p. 154ff .; Robert G. Hoyland: In God's Path. Oxford 2015, p. 49ff .; Michael Morony: Iran in the Early Islamic Period. In: Touraj Daryaee (ed.): The Oxford Handbook of Iranian History. Oxford 2012, pp. 208ff .; Hugh Kennedy: The Great Arab Conquests. Philadelphia 2007, pp. 98ff. and 169ff.

- ↑ At the time, see James Howard-Johnston: Witnesses to a World Crisis. Oxford 2010, pp. 116f.

- ↑ See Hugh Kennedy: The Great Arab Conquests. Philadelphia 2007, p. 108ff.

- ^ Hugh Kennedy: The Great Arab Conquests. Philadelphia 2007, p. 126ff.

- ↑ See Hugh Kennedy: The Great Arab Conquests. Philadelphia 2007, pp. 170f.

- ^ Hugh Kennedy: The Great Arab Conquests. Philadelphia 2007, pp. 171ff.

- ^ Hugh Kennedy: The Great Arab Conquests. Philadelphia 2007, p. 171.

- ↑ Sebeos 141.

- ↑ See Lutz Berger: The emergence of Islam. The first hundred years. Munich 2016, p. 178ff.

- ↑ Touraj Daryaee: When the End is Near: Barbarized Armies and Barracks Kings of Late Antique Iran. In: Maria Macuch et al. (Ed.): Ancient and Middle Iranian Studies. Wiesbaden 2010, pp. 43–52.

- ↑ See article Asawera in: Encyclopædia Iranica ; however, they soon lost their privileged status.

- ↑ See Abd al-Husain Zarrinkub: The Arab Conquest of Iran and Its Aftermath. In: The Cambridge History of Iran. Volume 4 ( The period from the Arab invasion to the Saljuqs ). Cambridge 1975, p. 28.

- ^ Hugh Kennedy: The Great Arab Conquests. Philadelphia 2007, pp. 173ff.

- ↑ See basically Patricia Crone : The Nativist Prophets of Early Islamic Iran. Rural Revolt and Local Zoroastrianism. Cambridge 2012.

- ^ Robert G. Hoyland: In God's Path. Oxford 2015, pp. 85f.

- ^ Hugh Kennedy: The Great Arab Conquests. Philadelphia 2007, pp. 187ff.

- ↑ Cf. Matteo Compareti: The last Sasanians in China. In: Eurasian Studies 2 (2003), pp. 197-213.

- ↑ Monika Gronke : History of Iran . Munich 2003, p. 17f. On the Islamization of Iran and identity formation, see Sarah Bowen Savant: The New Muslims of Post-Conquest Iran. Cambridge 2013.

- ↑ On the Arab conquest of Central Asia, see still Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen Gibb : The Arab Conquests in Central Asia. London 1923 ( digitized ).

- ↑ For the historical context for this area in late antiquity up to the fall of the Sassanid Empire, see Khodadad Rezakhani: ReOrienting the Sasanians. East Iran in Late Antiquity. Edinburgh 2017; especially for the following period see Douglas Haug: The Eastern Frontier. Limits of Empire in Late Antique and Early Medieval Central Asia. London / New York 2019. In general, see Christoph Baumer : The History of Central Asia. Vol. 2. London 2014.

- ^ Robert G. Hoyland: In God's Path. Oxford 2015, p. 150.

- ↑ See Robert G. Hoyland: In God's Path. Oxford 2015, pp. 181ff .; Hugh Kennedy: The Great Arab Conquests. Philadelphia 2007, pp. 225ff.

- ^ Christopher Beckwith: The Tibetan Empire in Central Asia. Princeton 1987, p. 108 ff.

- ^ Robert G. Hoyland: In God's Path. Oxford 2015, p. 184.

- ↑ Cf. currently Minoru Inaba: Across the Hindūkush of the ʿAbbasid Period. In: DG Tor (Ed.): In The ʿAbbasid and Carolingian Empires. Comparative Studies in Civilizational Formation. Leiden / Boston 2018, p. 123 ff.

- ^ Robert G. Hoyland: In God's Path. Oxford 2015, p. 185.

- ^ Robert G. Hoyland: In God's Path. Oxford 2015, pp. 186f.

- ^ Robert G. Hoyland: In God's Path. Oxford 2015, pp. 190-195; Hugh Kennedy: The Great Arab Conquests. Philadelphia 2007, pp. 296-308.

- ↑ For a summary of the war at sea, see Hugh Kennedy: The Great Arab Conquests. Philadelphia 2007, p. 324ff. Ekkehard Eickhoff is more detailed: Naval Warfare and Maritime Politics between Islam and the West. The Mediterranean under Byzantine and Arab hegemony. Berlin 1966.

- ↑ Cf. Ralph-Johannes Lilie: The Byzantine reaction to the expansion of the Arabs. Munich 1976, p. 122ff.

- ^ Marek Jankowiak: The first Arab siege of Constantinople. In: Travaux et Mémoires du Center de Recherche d'Histoire et Civilization de Byzance. Vol. 17. Paris 2013, pp. 237-320.

- ^ Leslie Brubaker, John F. Haldon: Byzantium in the Iconoclast era, ca 680-850. A history. Cambridge 2011, pp. 70ff.

- ^ Robert G. Hoyland: In God's Path. Oxford 2015, pp. 188-190.

- ↑ Cf. Ulrich Nonn: Die Schlacht bei Poitiers 732. Problems of historical judgment formation . In: Rudolf Schieffer (Ed.): Contributions to the history of the Regnum Francorum. Lectures at the Scientific Colloquium on the occasion of Eugen Ewig's 75th birthday on May 28, 1988. Sigmaringen 1990, pp. 37–56 ( digital-sammlungen.de ).

- ↑ See for example Warren Treadgold : The Byzantine Revival, 780-842 . Stanford 1988, p. 248ff.

- ↑ Cf. Ekkehard Eickhoff: Sea war and sea politics between Islam and the West. The Mediterranean under Byzantine and Arab hegemony. Berlin 1966, p. 65ff. and p. 173ff.

- ↑ See Hugh Kennedy: The Great Arab Conquests. Philadelphia 2007, pp. 13f.

- ↑ Julius Wellhausen: The Arab Empire and its fall. Berlin 1902, p. 136f.

- ↑ See for example Berliner Papyrusdatenbank P 13352 , P 13997 and P 25040 .

- ^ Hugh Kennedy: The Great Arab Conquests. Philadelphia 2007, p. 11.

- ↑ Petra M. Sijpesteijn: Shaping a Muslim State. The World of a Mid-Eighth-Century Egyptian Official. Oxford 2013.

- ↑ Cf. generally on the state structures in the early caliphate, for example Lutz Berger: The emergence of Islam. The first hundred years. Munich 2016, p. 249ff.

- ↑ With reference to the Egyptian case study, cf. the following two (complementary) studies: Maged SA Mikhail: From Byzantine to Islamic Egypt. Religion, Identity and Politics after the Arab Conquest. London / New York 2014; Petra M. Sijpesteijn: Shaping a Muslim State. The World of a Mid-Eighth-Century Egyptian Official. Oxford 2013.

- ↑ Cf. in principle Adel Theodor Khoury : Tolerance in Islam. Munich / Mainz 1980.

- ↑ Overview in Gilbert Dragon, Pierre Riché and André Vauchez (eds.): The history of Christianity. Volume 4: Bishops, Monks and Emperors (642-1054) . Freiburg et al. 1994, p. 391ff.

- ^ Adel Theodor Khoury: Tolerance in Islam. Munich / Mainz 1980, pp. 31-33.

- ↑ On the relationship between Zoroastrianism and Islam, see introductory Shaul Shaked: Islam. In: Michael Stausberg, Yuhan Sohrab-Dinshaw Vevaina (Ed.): The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Zoroastrianism. Chichester 2015, pp. 491-498.

- ↑ See Shaul Shaked: Islam. In: Michael Stausberg, Yuhan Sohrab-Dinshaw Vevaina (Ed.): The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Zoroastrianism. Chichester 2015, here pp. 492–495.

- ^ Willis Barnstone, Marvin Meyer The Gnostic Bible: Revised and Expanded Edition. Boston 2009, p. 803.

- ^ Adel Theodor Khoury: Tolerance in Islam. Munich / Mainz 1980, p. 171ff.

- ^ Adel Theodor Khoury: Tolerance in Islam. Munich / Mainz 1980, p. 146f.

- ↑ See Adel Theodor Khoury: Tolerance in Islam. Munich / Mainz 1980, p. 147f.

- ↑ On compulsory obligations see Adel Theodor Khoury: Tolerance im Islam. Munich / Mainz 1980, pp. 90f.

- ↑ On the legal status see also Adel Theodor Khoury: Tolerance im Islam. Munich / Mainz 1980, p. 138ff.

- ^ Adel Theodor Khoury: Tolerance in Islam. Munich / Mainz 1980, pp. 47-52.

- ^ Adel Theodor Khoury: Tolerance in Islam. Munich / Mainz 1980, p. 52f.

- ↑ See Wolfgang Kallfelz: Non-Muslim subjects in Islam. Wiesbaden 1995, p. 149.

- ↑ See Adel Theodor Khoury: Tolerance in Islam. Munich / Mainz 1980, p. 89f.

- ↑ Wolfgang Kallfelz: Non-Muslim subjects in Islam. Wiesbaden 1995, p. 46ff .; Milka Levy-Rubin: Non-Muslims in the Early Islamic Empire: From Surrender to Coexistence. Cambridge 2011, p. 100ff.

- ↑ Wolfgang Kallfelz: Non-Muslim subjects in Islam. Wiesbaden 1995, p. 49f. and p. 151f.

- ↑ Wolfgang Kallfelz: Non-Muslim subjects in Islam. Wiesbaden 1995, p. 50.

- ↑ Wolfgang Kallfelz: Non-Muslim subjects in Islam. Wiesbaden 1995, p. 51.

- ↑ Milka Levy-Rubin: Non-Muslims in the Early Islamic Empire: From Surrender to Coexistence. Cambridge 2011, p. 101.

- ↑ See the detailed overview in Milka Levy-Rubin: Non-Muslims in the Early Islamic Empire: From Surrender to Coexistence. Cambridge 2011, p. 102ff.

- ↑ On these measures directed against non-Muslims, see the summary in Wolfgang Kallfelz: Non-Muslim Subjects in Islam. Wiesbaden 1995, pp. 51-54 and pp. 150-152.

- ↑ Bertold Spuler : The oriental churches. Leiden 1964, p. 170.

- ↑ See, for example, the history of Christianity. Vol. 4: Bishops, monks and emperors (642-1054) . Edited by G. Dagron / P. Riché / A. Vauchez. German edition ed. by Egon Boshof. Freiburg et al. 1994, p. 395f. and p. 430.

- ↑ Cf. in summary Wolfgang Kallfelz: Non-Muslim subjects in Islam. Wiesbaden 1995, pp. 150-152.

- ↑ Wolfgang Kallfelz: Non-Muslim subjects in Islam. Wiesbaden 1995, p. 130.

- ↑ On the “view of the vanquished” see Hugh Kennedy: The Great Arab Conquests. Philadelphia 2007, pp. 344ff .; on non-Muslim sources, see Robert G. Hoyland: Seeing Islam as Others Saw It. A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam. Princeton 1997.

- ↑ For a summary and with further literature see Chris Wickham : The Inheritance of Rome. A History of Europe from 400 to 1000 . London 2009, pp. 285-288.

- ↑ See Wolfgang Kallfelz: Non-Muslim subjects in Islam. Wiesbaden 1995, p. 153.

- ^ Walter E. Kaegi: Heraclius. Cambridge 2003, pp. 221f.

- ↑ See Michael Morony: Iran in the Early Islamic Period . In: Touraj Daryaee (ed.): The Oxford Handbook of Iranian History . Oxford 2012, pp. 208-226.

- ^ For a summary of the Eastern Roman tax policy in the 7th century, see John Haldon: Byzantium in the Seventh Century. 2nd edition Cambridge 1997, pp. 141ff.

- ↑ Briefly summarizing Wolfram Brandes: Herakleios and the end of antiquity in the east. Triumphs and defeats . In: Mischa Meier (Ed.), You created Europe . Munich 2007, pp. 248-258, here p. 257. For criticism of the view that miaphysite disloyalty had favored the Arab conquest, see, for example, John Moorhead: The monophysite response to the Arab invasions. In: Byzantion 51 (1981), pp. 579-591; Harald Suermann: Copts and the Islam of the Seventh Century. In: Emmanouela Grypeou, Mark Swanson, David Thomas (eds.): The Encounter of eastern Christianity with early Islam (The History of Christian-Muslim Relations 5). Leiden / Boston 2006, pp. 95-109.

- ↑ See, for example, Walter E. Kaegi: Heraclius. Cambridge 2003, pp. 113f. and p. 126.

- ↑ See Robert G. Hoyland: In God's Path. Oxford 2015, pp. 94f.

- ↑ Cf. Heinz Halm : The Arabs. 2nd edition Munich 2006, p. 27f.

- ↑ See Robert G. Hoyland: In God's Path. Oxford 2015, pp. 158-164.

- ↑ See Robert G. Hoyland: In God's Path. Oxford 2015, p. 95.

- ↑ The detailed study by James Howard-Johnston : Witnesses to a World Crisis deals specifically with the problem of tradition . Oxford 2010.

- ↑ See, for example, Mark Whittow: The Making of Byzantium, 600-1025 . Berkeley 1996, p. 82ff.

- ↑ This applies e.g. B. for Hugh Kennedy ( The Great Arab Conquests , pp. 12ff.) And Fred Donner ( Muhammad and the Believers , pp. 91f.).

- ↑ See Karl-Heinz Ohlig (Ed.): The early Islam. A historical-critical reconstruction based on contemporary sources . Berlin 2007. Christoph Luxenberg argues that the Koran is essentially a faulty translation of a Syrian Christian treatise into Arabic : The Syro-Aramaic reading of the Koran: A contribution to deciphering the Koran language . Berlin 2011. For justified criticism, see for example Lutz Berger: The emergence of Islam. The first hundred years. Munich 2016, p. 264ff .; Tilman Nagel : Mohammed: Life and Legend . Munich 2008, p. 838f. A mediating position is taken by Fred Donner, who assumes that Mohammed envisaged a monotheistic movement of all believers that included Christians (and Jews) and that Islam did not develop in a different direction and into an independent religion until the early 8th century (Fred Donner: Muhammad and the Believers. Cambridge MA et al. 2010, p. 56ff. And p. 194ff.).

- ↑ Robert G. Hoyland: Seeing Islam as Others Saw It. A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam. Princeton 1997.

- ↑ See on this now Robert Hoyland (Ed.): Theophilus of Edessa's Chronicle and the Circulation of Historical Knowledge in Late Antiquity and Early Islam ( Translated Texts for Historians 57). Liverpool 2011.