Höfats

| Höfats | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Höfats from the northeast from Himmelecksattel ( 2007 m ) |

||

| height | 2259 m above sea level NHN | |

| location | Bavaria , Germany | |

| Mountains | Höfats and Rauheck Group , Allgäu Alps | |

| Dominance | 2.7 km → Little Wilder | |

| Notch height | 478 m ↓ Älplesattel | |

| Coordinates | 47 ° 22 '3 " N , 10 ° 20' 56" E | |

|

|

||

| Type | Allgäu Grasberg | |

| rock | Aptych and chert limestone on a base of Lias marl | |

| First ascent | 1848 by O. Sendtner | |

|

The four peaks of the Höfats from the north |

||

|

Höfats from the south of the Kreuzeck |

||

The Höfats is a 2259 m high mountain in the Allgäu Alps . Located near Oberstdorf , together with the Rauheck and other smaller peaks, it separates the Oytal from the Dietersbachtal . As the most distinctive Allgäu grass mountain with very steep slopes, it is unique in the Eastern Alps .

Location and surroundings

The Höfats has a total of four almost equally high peaks, which is why in the past it was compared to a Gothic cathedral because of its slender and rising lines.

The four peaks of the Höfats are divided into two pairs of peaks , which are separated from each other by the Höfatsscharte (2207 m). Between the peaks of the two pairs of peaks there are smaller cuts (approx. 2233 m and 2227 m). All the peaks sit on the ridge that runs from the Rauheck to the northwest.

From the east summit (2259 m) a ridge runs to the southeast to the Älpelesattel as well as an edge to the east-southeast, which contains an overhanging spike in the middle area ( Höfatszahn ). Between the ridge and the ridge is the southeast face of the east summit. Furthermore, the east summit sends an insignificant ridge to the southwest, which separates the Bergangertobel in the east from the Höfatswanne in the west.

The middle summit (2257 m) following the east summit is actually only an approx. 20 m long, horizontal edge which, apart from the two main ridges, has only one ridge sloping towards the southwest, which ends in the Höfatswanne like a pillar. At the foot of this ridge is a cave ( Höfatsgufel or Gufel ). On the east side, the central summit lacks a corresponding ridge. Instead, the wall here drops several hundred meters, partially overhanging, into the Red Hole .

At the Second Summit (2258.8 m) following the Höfatsscharte, the longest ridge in the Höfats area loosens to the northeast. This initially drops steeply into the Scharte ( Schärtele ) between Höfats and Kleiner Höfats and continues in the northeast ridge of the Kleine Höfats. The north walls of the second summit partly fall vertically into the Rauhen Hals . Below the foot of the wall there is a striking rock needle, the Höfatsnadel .

The west summit (2257.7 m) is connected to the second summit by a ridge that is not very indented. To the north, the west summit sends the north ridge, which rests steeply on the Rauhenhalsgrat . The ridge, which extends to the southwest and is covered with rock towers, limits the Höfatswanne to the west.

Naming

The meaning of the name Höfats

The name Höfats (in the Oberstdorf dialect [ 'heəfats ]) have already been tried many times . It has often been interpreted as a name with Romance origins. The field name researcher Ludwig Mayr believed that the name could be traced back to a name Herfart (Harifrid), who created an alp on the Höfats, which ultimately gave the mountain its name. Likewise, an interpretation of the name as Die Hoffärtige (because of the majestic shape of the mountain) used to be widespread, although this was already described in the 1951 Alpine Club Guide as “daring”.

August Kübler made the first professional attempt at interpreting the name as early as 1909. In his opinion, the name is the “part. preaes. neuter of the verb heben… ”meaning“ where everything rises, where everything rises ”. Thaddäus Steiner was able to refute this interpretation in his dissertation from 1972 due to his detailed knowledge of the grammar of the Oberstdorf dialect. At that time Steiner was unable to provide a perfect interpretation of the name.

It wasn't until the 21st century that Thaddäus Steiner proposed a plausible interpretation that almost certainly explains the name correctly. His interpretation is based on the fact that the lower areas of the Höfats served the village of Gerstruben as goat pasture (i.e. pasture for goats) for many centuries and that the word Atz means pasture in the Walser dialect (Gerstruben is an old Walser settlement). Together with the fact, already described in his dissertation in 1972, that a Middle High German -ch is often spoken as -f in Oberstdorf dialect, this results in consideration of the fact that in Oberstdorf dialect a long -ö- is pronounced as e als the meaning of Höchatz (= high pasture). The name was transferred from this high pasture to the mountain.

Names of the individual peaks

The names of the individual peaks and the altitude information vary in the literature and in the individual maps. The altitude information is most detailed in the “Allgäuer Alpen West” Alpine Club map . According to her, the summit structure of the Höfats consists of the following individual peaks from north-west to south-east: west summit, second summit, middle summit, and east summit.

Until the 19th century it was decisive for the name to be given that the steep grass flanks in the lower area of the mountain were cultivated from the village of Gerstruben . Since Gerstruben is located west of the Höfats, the west summit was called the front summit , the second summit was called the secondary summit and the east summit was called the rear summit . Only the central summit used to have the same name. Only after the appearance of the first Alpine Club map "Allgäuer Alpen West" in 1906 were the terms West Summit , Second Summit and East Summit used.

The new edition of the Alpine Club Guide from 2004 rejects the previously used terms “West Summit” and “East Summit”. "Northwest summit" and "Southeast summit" are suggested as a more appropriate designation. Since the literature and most maps predominantly use the terms Westgipfel and Ostgipfel , this article also uses these names.

geology

The Höfats is made up of gray aptych limestone , which comes from the younger Jurassic period . These aptych limestones are surrounded by a layer of pebbly, red chert limestone, which reach the summit ridge on both sides of the Höfatsscharte and which are responsible for the red color of the red hole falling to the east . Below the chert layers of the base made occurs Lias - spot marl indicate what can clearly be seen in the rise from the trough to the west summit. The aptych layers build up the daring spikes (for example on the Höfats needle ) and sharp ridges on the Höfats .

Botany and nature conservation

The Höfats is known far beyond the Allgäu for its diversity of plants . Many plants have their only location in the Allgäu Alps and the Bavarian Alps due to the pebble content of the chert and the aptych limestone on the Höfats. In addition to the gentian , auricle and anemone , you will also find the rare rue , the strange feather grass , the ostrich bellflower and, last but not least, the edelweiss , which used to be very numerous here and made the Höfats famous.

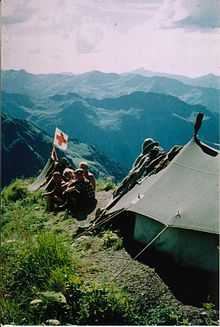

At the beginning of the 20th century, the edelweiss on the Höfats was almost exterminated, although the mountain had been a plant protection area since 1911. Especially at the time of the inflation in 1923 , the edelweiss was picked in clusters in order to be able to sell it to tourists in Oberstdorf at the train station. In the mid-1920s, therefore, the edelweiss population at the Höfats was only 10% of the population in 1900. This development prompted the Allgäu mountain rescue team, led by Georg Frey, to set up a tent post on a horizontal rib below the Höfatsgufel to around 2,000 from 1935 m height, which was constantly manned from June to September by two mountain guards (with weekly replacement). These monitored the steep flanks of the Höfats for mountaineers who collected edelweiss. If necessary, they had to track down the presumed edelweiss predators and, if necessary, prevent them from picking them. This enabled the last remaining edelweiss stocks to be saved from final extinction. In addition, the constant presence of the mountain rescue service reduced the number of fatal crashes rapidly. In 1959 the Höfats area was declared a nature reserve. Thanks to the constant guarding of the edelweiss stocks, they had grown again to 80% of the level in 1900 by the beginning of the 1970s. There are now edelweiss canes with 30 or more flowers at the Höfats.

Since the stay for the mountain guards in bad weather, thunderstorms or the onset of summer winter in the tent was anything but pleasant, at the end of the 1960s, the Kemptner mountain guard Wolfgang Bedau, the then on-call manager Kurt Bogner and the mountain rescue section manager Georg Frey, the idea of replacing the Put up a bivouac box in the tent . In 1969 the aluminum bivouac box was built together with members of the Neu-Ulm mountain rescue service and set up on the square below the Höfatsgufel with the help of a helicopter.

In memory of the merits of Georg Frey, the mountain rescue base at the Höfats is now called Georg Frey base .

Since the edelweiss stocks have now recovered and the mountaineers' environmental awareness no longer requires permanent monitoring, the mountain rescue base has not been manned since 2007.

Alpinism

Mountaineering development

The mountaineering development of the Höfats can be divided into four epochs. The first epoch comprised the part of the ascension story that Anton Spiehler (* 1848 in Bayreuth ; † June 18, 1891 in Memmingen ) describes in his treatise on the development of the Eastern Alps. The second period is the one that Fritz Schmitt than Allgäu school referred to and which is inseparably linked with the Brothers Enzensperger. In the third epoch in the first half of the 20th century, activities shifted to the north walls, where more and more locals were again carrying out the first ascent . After all, the fourth epoch in the second half of the 20th century was first characterized by a spectacular winter ascent and towards the end of the 20th century by the rediscovery of the extreme climbs in the north faces by Allgäu sport climbers .

The history of the ascent until 1890

Long before the first known tourist ascent in 1848 by the botanist Otto Sendtner , the western summit of the Höfats was climbed by locals from Gerstruben. The general public only became aware of this ascent in 1853 in a report by Sendtner in a supplement to the Allgäuer Zeitung. During this time, the two local hunters Thaddäus Blattner (* Dec. 1824 in Oberstdorf; † March 17, 1895 in Oberstdorf) and Leo Dorn (later the Eagle King ) carried out climbs that were only repeated by tourists four decades later. The first detailed ascent report comes from the year 1858 by Dr. Large , in which the enormous inclination of the flanks was described for the first time with information between 70 ° and 80 °, which in 1869 the developer of the Allgäu Alps, Hermann von Barth, underestimated. Despite (or perhaps because of) the terrifying description, the Höfats found their lovers, so that it became known in wider circles outside the Allgäu and was also climbed more frequently by tourists. Spurred on by Dr. In the years that followed, the inclination of the ascents was largely determined by the hikers, for example by Hermann von Barth, who reported inclination angles of 80 to 82 ° on his ascent of the western summit, while a Dr. Maschke from Berlin mentions the inclination in much more detail ("never below 60 ° ... often greater than 70 ° ... steepest point 79 °").

The Allgäu School

Until the beginning of the 1890s, the climbs that had been climbed so far were occasionally repeated by tourists accompanied by guides. The central summit was still unclimbed at that time. At that time, even such profound Höfats connoisseurs like Th. Blattner believed that the central summit was inaccessible, although Blattner (next to Leo Dorn) was one of the best grass walkers at the time, which he made through his numerous ascents (e.g. 20-30 up or downhill) . Descents over the north ridge of the west summit) had demonstrated. The middle summit was finally climbed for the first time in 1891 by H. Kranzfelder and Ludwig Stritzel from the Höfatsscharte. In that year Josef Enzensperger ascended the Höfats together with Karl Neumann. In 1892, Enzensperger founded the Academic Alpine Association (AAVM) together with 11 mountain-loving students in Munich . This AAVM donated the first Höfats summit book in 1893 , which gave a boost to driverless tourism in the Allgäu, especially on the Höfats. In 1892, H. Kranzfelder made the usual ascent to the east summit from Älpelesattel and in the same year, together with Ludwig Stritzl and Ernst Platz, he made the first crossing from the west to the east summit, which is still popular today. At that time the use of ice ax and crampons gradually gained acceptance , which in the following period left real trenches with the relatively frequent inspections of the normal routes to the east and west peaks. The significantly more difficult crossing from the east to the west summit was achieved by the brothers Josef and Ernst Enzensperger in 1893. Finally, in 1895, the Enzensperger brothers, together with their three friends, "grass specialists" Emanuel Christa , Julius Bachschmid and Weissler from Kaufbeuren, were able to do the most daring grass tour at the time des Allgäu ”: the descent from the east summit over its south-east face. On this 400 m high descent into the Red Hole , it was made more difficult that Josef Enzensperger noticed after overcoming the most difficult part that his brother's backpack had been left lying further up. Since you didn't want to leave your rucksack behind, this passage had to be climbed up and down again. Ernst Platz recorded this first ascent in a contemporary drawing that appeared in the Alpine Club yearbook of 1896. Finally, Th. Spindler and companions managed the first tourist ascent of the southwest ridge of the west summit, which, according to Spiehler, had been climbed by Th. Blattner many years earlier.

The development of the north walls

In the next 25 years, the development of further climbs on the Höfats was quiet. On the one hand, all the easier climbs had already been climbed, on the other hand, the climbing and safety technology was not yet advanced enough to enable the as yet unclimbed walls to be climbed. It was not until 1930 that the roped team Franz Faschingleitner and Ludwig Zint from Oberstdorf managed to climb the west face of the west summit, which caused a sensation at the time. Their description of the ascent could still be found decades later in many editions of the older Alpine Club guides. Two years later the same team managed the first north face route on the Höfats, the western lead through the north face to the second summit. In the next few years, the Anton Stolze (* 1901; †?) And Sepp Prinz (* 1901; † 1998) team from Immenstadt were very successful. Their eastern route through the north face to the second summit had the flaw that the guide ended about 2 pitches (60 m) below the summit on the northeast ridge of the second summit. What is remarkable about this ascent, however, is the fact that the ascent was carried out at Easter 1934 when it was partially iced over. In the following year, this team managed to climb the direct north face of the Second Summit, which is still occasionally repeated today and which is considered the classic north face lead on the Höfats. On this ascent, the first climbers had to overcome two pitches of extreme difficulty. Finally, in 1933 Anton Stolze and Kaspar Schwarz (* 1909 in Oberstdorf, † 1991 in Oberstdorf) succeeded in the first ascent of the straight north face of the east summit.

Winter ascent and rediscovery of the extreme climbs

After the Second World War, the extreme routes on the Höfats were rarely used. The first winter ascent of the direct north face of the Second Summit by Georg Maier (1911–1977) and Hannes Niederberger caused a stir in 1955 . Maier, who comes from Ulm, was by far the most successful winter mountaineer in Germany at the time and made the first winter ascent of the Höfats north face (the second winter ascent was only carried out over 50 years later in winter 2008/2009 by Michael Schafroth and Florian Jehle) and the subsequent descent the southwest ridge clearly demonstrates its skills. In the 1980s and 1990s, the north face routes were occasionally used by local extreme climbers, which was partly documented by reports in the press. The north face of the Second Summit was first climbed since 1962 in June 1998 by Matthias Robl and Bernhard Hauber (6th ascent) and shortly afterwards again by Toni Steurer (* 1978) and Michael Schafroth on June 21, 1998 (7th ascent) . The rope team Matthias Robl and Toni Steurer succeeded in repeating the north face of the east summit in the summer of 1999. Finally, the ascent style of an enchaînement, known from the Great Alpine Walls, was established in 1999 by Toni Steurer at the Höfats, when the Oberstdorfer climbed all the Höfatsgrate one after the other on one day: ascent over the southwest ridge to the west summit, descent over the north ridge, again ascent over the north ridge , Crossing to the east summit, descent over the southeast ridge into the Rote Loch , ascent via the northeast ridge to the second summit, crossing again to the east summit, descent to the Gufel. More than 100 years ago, the hunter Blattner had already carried out such a stringing together of several (albeit easier) climbs several times in the course of his work.

Chronological overview of important ascents

- 1848, O. Sendtner : West summit of Gufel (normal route)

- around 1855, Th. Blattner : West summit, north ridge

- around 1855, Th. Blattner : Second summit, northeast ridge

- 1856, L. Dorn : Höfatsscharte from the Red Hole

- 1891, H. Kranzfelder, L. Stritzel : Central summit of Höfatsscharte

- July 28, 1891, H. Kranzfelder, L. Stritzel : East summit from Älpelesattel

- 1892, H. Kranzfelder und Gef .: Crossing from the west to the east summit

- 1893, J. Enzensperger, E. Enzensperger : Crossing from the east to the west summit

- 1895, J. Enzensperger, E. Enzensperger, Christa, Bachschmid, Weissler : Ostgipfel-Südostwand (on the descent!)

- 1895, E. Heimhuber, Zink : Ostgipfel von Gufel

- 1897, J. Enzensperger and Gef .: Crossing from the west to the east summit (1st winter ascent)

- 1904, Th. Spindler and Gef .: Westgipfel, Südwestgrat

- 1930, F. Faschingleitner, L. Zint : Westgipfel, Westwand

- 1932, F. Faschingleitner, L. Zint : Second summit, north face, western lead

- 1933, A. Stolze, K. Schwarz : Ostgipfel, Nordwand

- March 31/1. April 1934, A. Stolze, S. Prinz : Second summit, north face, eastern guide

- June 30, 1935, A. Stolze, S. Prinz : Second summit, direct north face

- 9/10 April 1955, G. Maier, H. Niederberger : Second summit, direct north face (1st winter ascent)

- April 10, 1955, G. Maier, H. Niederberger : West summit, south-west ridge in descent (1st winter ascent)

- Winter 2008/2009: M. Schafroth, F. Jehle : Second summit, direct north face (2nd winter ascent)

Erection of the summit crosses

The erection of the summit cross is closely connected with the ascent of the summit . Since the western summit was climbed first, there was also a summit cross here, which the hunter Th. Blattner erected there between the years 1854 and 1857. However, this was no longer available in the 1890s, because Enzensperger only mentions a signal pole on the signal head (2004 m) on the south-east ridge of the east summit in his reports on the ascent of the Höfats and only cairns are shown on the peaks on the drawings. On July 15, 1923, the second cruiser was erected on the western summit by Oberstdorf mountain guides and almost 30 years later on May 29, 1951, the third cruiser was erected by the Oberstdorf section of the German Alpine Club. This summit cross stood for almost 30 years before it fell over and was replaced by a new cross in October 1983 by mountain guides from Oberstdorf. A helicopter was used here for the first time. In the 1990s the summit cross was still there, but without a summit book. The curiosity arose that a group of mountain climbers from Oberstdorf and members of the Kempten mountain rescue team made the decision to deposit a summit book at the western summit and both groups climbed the summit on the same day. The group of Oberstdorf mountaineers arrived at the summit about half an hour earlier, so that their summit book was at the western summit for the next few years.

Almost half a century after the first summit cross was erected on the western summit, mountain guides from Oberstdorf erected the first summit cross on the eastern summit on May 29, 1911 and deposited a summit book. Again, it took almost half a century until the second cross on the east summit was erected on September 20, 1958 by mountaineers from Kempten. Unfortunately, the crossbar of this cross was destroyed by a lightning strike in the summer of 1962, so that the crossbar had to be replaced on September 16, 1962. This summit cross withstood the weather for almost 15 years and had to be replaced by a new cross on July 2, 1977, which was knocked down by a storm just 5 years later in 1982. After the cross was erected on the east summit on July 10, 1983, the last summit cross on the east summit was erected at the beginning of August 2008 by the Kolping family Börwang .

There have never been summit crosses on the second summit or the middle summit. A cassette with a summit book is available at the central summit.

Climbs

The individual peaks are sometimes difficult to reach. As a result, hikers who overestimate themselves in the steep grass and craggy terrain keep falling. The more difficult climbs on the Höfats differ from other climbing tours in the Eastern Alps in that they combine grass and rocky areas with poor or no security options.

Equipment and best climbing conditions

In the past, climbing irons and ice ax were suggested in alpine literature for climbing the Höfats. The use of crampons resulted in real trenches being created on the normal routes. The use of crampons can now be dispensed with on the easier climbs, while experienced grass climbers use an ice ax or an ice ax, at least on the more difficult climbs. Instead of the crampons with front spikes, sturdy mountain boots with Tricouni fittings are recommended, although these shoes have the disadvantage that they are more difficult to walk on the rocky passages . In the pure grass area, however, the shoes with Tricouni fittings have the advantage of significantly improved step security. For the normal routes to the east and west peaks, sturdy mountain boots with a good profile are sufficient. In the past, ice hooks were sometimes recommended in the difficult climbs in the north walls because of the friable rock.

For the ascent on the Höfats, dry weather is absolutely recommended, because wetness and icing create conditions that can be compared with the serious conditions of an ice tour in the central Alps. However, a dry period that is too long is not ideal either, as in this case the earth becomes too dry and crumbly, which in turn makes climbing difficult.

Due to the nature of the rocks or the climbs, the demands on the mountaineer are much higher than on a pure rock climbing tour such as. B. in the Kaiser Mountains or in the Wetterstein . A good rock climber who is unsafe in the Schrofen terrain will almost certainly have problems on the Höfats due to the unreliable rock and the poor security options.

East summit

South-southeast ridge

- Difficulty: II

- Time required: 1¼ hours

- Starting point: Älplesattel

- First climbers: H. Kranzfelder, L. Stritzel, 1891

- Comment: One of the usual normal climbs

This climb is by far the most popular climb on the Höfats. This is because a clearly visible path in the direction of Höfats begins at the Älpelesattel. The way is still relatively easy in the lower area. After a short descent, however, it becomes steeper and steeper and more and more interspersed with rocks. Shortly before the summit, a slab of rock lying diagonally on the ridge represents the key point. Many mountaineers have to turn around here, because the slab is much more difficult to descend than to climb. To the west (on the left in the ascent) the ridge breaks off into the Höfatswanne with a 200 m high, partially vertical grass wall, while to the right the ridge drops into the south-east wall.

Towards the end of the 1990s, the mountain rescue service installed a bolt in the upper area of the rock slab so that this area can be better secured. Since in the following years a bolt was also attached in the lower area of the rock passage, the first one no longer has to cope with this point unsecured.

From the Gufel

- Difficulty: II

- Time required: ½ hour

- Starting point: Höfatsgufel

- First rider: E. Heimhuber, Zink, 1895

- Comment: One of the usual normal climbs

Southeast wall

- Difficulty: IV

- Time required: 2½ hours

- Starting point: Käseralpe

- First climbers: J. Enzensperger, E. Enzensperger, Christa, Bachschmid, Weissler, 1895 (in descent!)

- Note: hardly used any more, only of historical interest

North face

- Difficulty: VI

- Time required: 6½ hours

- Starting point: Red Hole

- First climbers: A. Stolze, K. Schwarz, 1933

- Note: very rarely used by locals

Second summit

Northeast ridge

- Difficulty: III

- Time required: 4 hours

- Starting point: Käseralpe

- First climber: Th. Blattner, around 1855

North face - western lead

- Difficulty: V

- Time required: 2 hours

- Starting point: Rauhenhalsalpe

- First climbers: F. Faschingleitner, L. Zint, 1932

- Note: hardly used any more, only of historical interest

North face - east lead

- Difficulty: VI

- Time required: (unknown)

- Starting point: Rauhenhalsalpe

- First climbers: A. Stolze, S. Prinz, 1934

- Comment: practically no longer committed, only of historical interest

Straight north face

- Difficulty: VI

- Time required: 10 hours

- Starting point: Rauhenhalsalpe

- First climbers: A. Stolze, S. Prinz, 1934

- Note: very rarely used by locals.

Of all the north face climbs on the Höfats, the straight north face of the second summit is likely to have been repeated the most, firstly because of the ideal alignment and secondly because of the popularity of this ascent through the report on the winter ascent by Georg Maier and Hannes Niederberger in the yearbook of the German Alpine Club 1966 obtained. The guide gained further notoriety through reports in the local press about ascents at the end of the 1990s. Finally, in the film Die Höfats - a unique mountain by Gerhard Baur from 2007, an inspection of this route was documented.

West summit

Through the tub

- Difficulty: II

- Time required: 3¼ hours

- Starting point: Gerstruben

- First climber: O. Sendtner, 1848

- Comment: One of the usual normal climbs

The normal route to the west summit is a frequently climbed ascent, which, however, is not climbed as often as the normal route to the east summit. It does not have a pronounced key point, but there are easy climbing points already in the lower part and just above the mountain rescue post. It is not as exposed as the path to the east summit. The steepness of the terrain increases continuously until you finally reach the summit ridge. Finding the way is a bit difficult above the mountain rescue post.

Southwest ridge

- Difficulty: IV

- Time required: 5 hours

- Starting point: Gerstruben

- First climbers: Th. Spindler and Gef., 1904

- Note: route used more frequently

The southwest ridge is a relatively frequent climb, as the ridge clears snow very quickly and is also interesting for rock climbers because of the rocky passages. He became known to a broader television audience through the film Die Höfats - a unique mountain by Gerhard Baur.

North ridge

- Difficulty: IV

- Time required: 3¼ hours

- Starting point: Gerstruben

- First climber: Th. Blattner, around 1855

West wall

- Difficulty: VI

- Time required: 4½ hours

- Starting point: Gerstruben

- First climbers: F. Faschingleitner, L. Zint, 1930

- Comment: practically no longer committed, only of historical interest

Others

Crossing from the west to the east summit

- Difficulty: III

- Time required: 1 hour

- Starting point: west summit

- First climbers: H. Kranzfelder and Gef., 1893

- Note: The crossing (also called traverses ) is a relatively frequent route.

It is still relatively easy and has impressive views down into the Red Hole , especially in the gap between the central summit and the eastern summit. It became known to a broad television audience in the early 1990s through the program Bergauf-Bergab , when the Oberallgäu mountain guide Udo Zehetleitner and Hermann Magerer , the program presenter, set out on the route.

From the west summit, the route leads on climbing tracks through the steep southern flank of the second summit into the Höfatsscharte. The Höfatsscharte can also be reached much more difficult directly via the ridge and the second summit. In front of the saddle, the central summit is climbed over unreliable rock. You descend over flat, grass-strewn rocks into the following notch in front of the east summit. Only then do you have reasonably good security options. A large boulder in the gap offers a good base. From the saddle it goes up to the east summit over easy-grip, relatively solid rocks very exposed. This guide is also sometimes used by locals on their own without ropes. In the opposite direction, the route is much more demanding, as the difficult passages have to be climbed on the descent.

Accidents

Because of the richness of edelweiss in the Höfats, many mountaineers were tempted to climb the steep flanks in the past. This resulted in many fatal crashes for which the Höfats were notorious. It was only through the constant manning of the mountain rescue post that the number of fatal crashes decreased significantly. Nevertheless, there are still fatal crashes these days. On the one hand the cause lies in the self-overestimation of the hikers and on the other hand in bad weather conditions or the geological conditions. The normal routes to the east and west peaks, which are relatively easy to walk under normal conditions for experienced mountaineers, become very dangerous when wet, iced or covered in snow. Due to the nature of the terrain, every misstep or slip on the Höfats can be fatal. In the last few decades there has been at least one fatal crash at the Höfats almost every year.

In the Höfats area, mountaineers are repeatedly reminded of fatal falls by memorial crosses, for example at the Öfenstein (about halfway between Gerstruber Alpe and Dietersbachalpe) of the fatal fall of the mountain guard Eduard Kiefer on July 26, 1936 or at the Stairs (at the beginning of the northeast ridge of the Kleine Höfat ) to the fatal fall of a mountaineer in 1957.

Paragliding

The first documented paragliding flight from Nebelhorn to Höfats was made in 1988 by Dominik Müller from Oberstdorf, which was a sensation with the performance of the paragliders at the time. He used a Firebird Extase , which with a glide ratio of 4.5 was not designed for the flight to the Höfats. In the next few years the Höfats became the preferred destination for paragliders due to the improved flight characteristics of paragliders.

Nevertheless, a flight to Höfats is only reserved for experienced paraglider pilots. On the one hand because of the strong thermals over the steep grass flanks (especially during spring) and on the other hand because the rescue parachute can be used in the event of problems , but a (possibly fatal) fall in the very steep grass flanks cannot be excluded after the impact.

More pictures

Höfats from the north, from the Himmelhorn

Hüttenkopf (left) from Älpelekopf , right (a little higher) the Höfats

Schneck (summit to the right of the center of the picture) with its east wall from the northeast. The mountain on the left is the Wiedemer head , with the Höfats in the background. On the right edge of the picture the three peaks of the Rotkopf .

literature

- The beautiful Allgäu . 1937, p. 117

- The beautiful Allgäu . 1969, p. 159

- Joseph Enzensperger: The Höfats in the Allgäu . In: DÖAV magazine , 1896

- Georg Frey: Allgäu grass mountains . In: DAV 1963 yearbook

- Georg Frey: On the Allgäu mountains . Kempten 1963

- Volker Jacobshagen : From the geological structure of the Allgäu Limestone Alps . In: DAV Yearbook , 1966

- Georg Meier: Winter mountaineering in the Allgäu Alps . In: DAV Yearbook , 1966

- EA Pfeiffer: The Höfats . In: Oberstdorf im Allgäu - Eternal mountains, sun and snow . Verlag Buchdruckerei A. Hofmann, Oberstdorf o. J.

- Spiehler: Development of the Eastern Alps . Berlin 1893

- Thaddäus Steiner: The field names of the municipality of Oberstdorf im Allgäu , Volume II. Self-published by the Association for Field Name Research, Munich 1972

- Thaddäus Steiner : Allgäu mountain names . Kunstverlag Josef Fink, Lindenberg 2007, ISBN 978-3-89870-389-5 , p. 96 .

- Thaddäus Steiner: Höfats - attempt at a name interpretation . In: Our Oberstdorf , sheets on Oberstdorfer Heimatgeschichte, issue 50/2007, p. 1847.

- Ernst Zettler, Heinz Groth: AVF Allgäu Alps . Bergverlag Rudolf Rother, Munich 1984, ISBN 3-7633-1111-4 .

Movies

- The Höfats - the unique mountain . Film by Gerhard Baur , 2007

- Contribution in Bergauf-Bergab , around 1992

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Ernst Zettler, Heinz Groth: Alpine Club Guide Allgäu Alps . Bergverlag Rudolf Rother , Munich 1951, p. 214

- ^ Ernst Zettler, Heinz Groth: Alpine Club Guide Allgäu Alps . Bergverlag Rudolf Rother, Munich 1951, p. 214f

- ↑ a b Georg Frey: Allgäu grass mountains . Yearbook of the DAV 1963, p. 29

- ↑ a b Thaddäus Steiner: Höfats - attempt at a name interpretation . In: Our Oberstdorf , sheets on Oberstdorf local history. Issue 50/2007, p. 1847

- ↑ August Kübler: The place, water and mountain names of the alpine Iller, Lech and Sannen area . Amberg 1909, p. 387

- ^ Thaddäus Steiner: The field names of the municipality of Oberstdorf im Allgäu , Volume II. Self-published by the Association for Field Name Research, Munich 1972, p. 152

- ↑ a b Thaddäus Steiner : Allgäu mountain names . Kunstverlag Josef Fink, Lindenberg 2007, ISBN 978-3-89870-389-5 , p. 96 .

- ^ Anton Spiehler: Development of the Eastern Alps . Berlin 1893, p. 82

- ^ Ernst Zettler, Heinz Groth: Alpine Club Guide Allgäu Alps . Bergverlag Rudolf Rother, Munich 1984, p. 398

- ↑ Volker Jacobshagen: From the geological structure of the Allgäu Limestone Alps . Yearbook of the DAV 1966, p. 42

- ↑ Whistle warned against temptation , article in the Süddeutsche Zeitung about the mountain rescue post, September 9, 1996

- ^ Website of Bergwacht Bayern

- ^ Georg Frey: Allgäu grass mountains . Yearbook of the DAV 1963, p. 31

- ^ Website of Bergwacht Bayern

- ↑ Michael Munkler: Bergwacht 65 years in the service of nature conservation . In: Allgäuer Anzeigeeblatt , October 4, 1994

- ^ Anton Spiehler: Development of the Eastern Alps . Berlin 1893, p. 78ff

- ^ A b Fritz Schmitt: Allgäuer Bergsteiger-Chronik . Yearbook of the DAV 1963, p. 18f

- ^ Anton Spiehler: Development of the Eastern Alps . Berlin 1893, p. 84

- ^ Anton Spiehler: Development of the Eastern Alps . Berlin 1893, p. 78.

- ↑ Oberstdorf death register

- ^ Georg Frey: Allgäu grass mountains . Yearbook of the DAV 1963, p. 30

- ^ Anton Spiehler: Development of the Eastern Alps . Berlin 1893, p. 80f.

- ↑ Helmut v. Bischoffshausen: Summit crosses on Oberstdorf mountains . In: Our Oberstdorf , sheets on Oberstdorf local history. Issue 13/1988, p. 267ff

- ^ Anton Spiehler: Development of the Eastern Alps . Berlin 1893, p. 81.

- ↑ a b c Anton Spiehler: Development of the Eastern Alps . Berlin 1893, p. 83.

- ↑ Robert Jaspers: Allgäu climbing guide . Akademische Verlagsanstalt, Leipzig 1998, p. 273.

- ^ Fritz Schmitt: Allgäuer Bergsteiger-Chronik . Yearbook of the DAV 1963, p. 23f

- ↑ Allgäuer Rundschau: Mountain films of a special kind ( Memento of the original from December 11, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , November 17, 2009

- ↑ Allgäuer Anzeigeeblatt , November 13, 2009

- ↑ a b Georg Meier: Winter mountaineering in the Allgäu Alps . DAV 1966 yearbook , p. 30

- ↑ a b Josef Gutsmiedl: In the footsteps of the first climbers of the Höfats . In: Kreisbote , July 3, 1998

- ↑ Peter Schwarz: "Höfats-Express": Extreme tour on the four-summit mountain . In: Allgäuer Anzeigeeblatt , September 25, 1999

- ↑ Ignaz Vogler: Oberstdorf and its mountains . Verlag Studio Tanner, Nesselwang 1981, ISBN 3-9800066-3-8 .

- ↑ Helmut v. Bischoffshausen: Summit crosses on Oberstdorf mountains . In: Our Oberstdorf , sheets on Oberstdorfer Heimatgeschichte, issue 13/1988, p. 269

- ^ Fritz Schmitt: Allgäuer Bergsteiger-Chronik . Yearbook of the DAV 1963, p. 21

- ↑ a b Helmut v. Bischoffshausen: Summit crosses on Oberstdorf mountains . In: Our Oberstdorf , sheets on Oberstdorfer Heimatgeschichte, issue 13/1988, p. 267f

- ↑ a b Helmut v. Bischoffshausen: Summit crosses on Oberstdorf mountains . In: Our Oberstdorf , sheets on Oberstdorf local history. Issue 17/1989, p. 359ff

- ^ Allgäuer Zeitung , August 22, 2008

- ^ Ernst Zettler, Heinz Groth: Alpine Club Guide Allgäu Alps . Bergverlag Rudolf Rother, Munich 1979, p. 295

- ↑ Michael Munkler: Mountaineer falls 300 meters into the depth . In: Allgäuer Anzeigeeblatt , October 7, 1996

- ↑ Michael Munkler: Bergwachtler falls to his death at Höfats . In: Allgäuer Anzeigeeblatt , July 23, 1999

- ↑ Mountaineer falls to his death at Höfats . In: Allgäuer Anzeigeeblatt , September 15, 2005

- ^ Identity of dead wanderer still unclear . In: Allgäuer Anzeigeeblatt , September 20, 2005, information from the police

- ↑ Georg Frey: SOS from the mountains . Verlag für Heimatpflege, Kempten 1960, p. 120

- ↑ Meinhard Kling: Information boards, memorial plaques, field crosses, wayside shrines and chapels in the Oberstdorf area . In: Our Oberstdorf , sheets on Oberstdorfer Heimatgeschichte, issue 4/1983, p. 175