Urinary tract infection

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| N39 | Urinary tract infection |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

Under a urinary tract infection , urinary tract infection (UTI), or a urinary tract infection is meant a by pathogens causing infectious disease of the lower urinary tract . The infection can spread to the kidneys and bloodstream and as a result lead to threatening clinical pictures. Urinary tract infections can be treated very successfully with antibiotics . Different drugs are used depending on the patient's risk potential. In uncomplicated cases, the disease often heals without medication. Non-drug interventions can promote healing.

distribution

The number of new cases in one year ( incidence ) is around 5% in younger women. It increases to around 20% with age. While urinary tract infections are rather rare in younger men, their risk becomes more similar to that of women as they get older. There are three total frequency peaks for urinary tract infections in the population. The first frequent occurrence is found in infants and small children , as these often have untreated malformations of the urinary tract. Smear infections are also more common in this age group . The second peak frequency affects adult women. It is attributed to the increased rate of infections during sexual activity and the increased susceptibility during pregnancy . Older people of both sexes are the third collective with an increased frequency of the disease. Reasons for this are narrowing of the urinary tract due to age-related degenerations such as prostatic hyperplasia or a prolapse of the uterus .

Urinary tract infections are among the most common infections acquired in hospital ( nosocomial ). A German study from the 1990s estimated the proportion of urinary tract infections in nosocomial infections to be over 40%.

Disease emergence

A urinary tract infection occurs in 95–98% of cases when the pathogen ascends via the urethra . In the remaining cases, the urogenital tract is infected via the bloodstream. The pathogen (usually bacteria ) come in most cases, the body's intestinal flora , go to the external urethral opening and hike up the urethra into the bladder , where it to a bladder infection ( cystitis cause, an inflammation of the lower urinary tract). If the ascent continues, it can lead to inflammation of the kidneys, including involvement of the kidney tissue itself ( pyelonephritis ), and eventually blood poisoning ( urosepsis ).

To do this, the pathogens have to overcome the body's own defense mechanisms. These consist of the fluid flow in the urinary tract, the urothelium , which counteracts the adhesion of bacteria, and IgA antibodies, which occur on the surface of the urothelium. This keeps the bladder free of germs in healthy people. The urine itself is only antibacterial against a few species and can even encourage the growth of many forms of pathogen. Factors that help the germs to ascend are the formation of a bacterial capsule , the production of hemolysins to dissolve red blood cells and the formation of thread-like cell organelles that allow bacteria to adhere to the surface tissue of the urinary tract, so-called pili . The receptor density for these pili is particularly high in the entrances of the vagina , the urinary bladder, the ureter and the renal pelvis.

In addition to these pathogen properties, numerous other possible host factors promote the development of a urinary tract infection. Instrumental interventions such as a cystoscopy or a urinary catheter are possible entry points. Malformations of the urinary tract, functional disorders of the bladder or a reduction in the flow of urine impair the flushing out of pathogens and thus facilitate their ascent. Also, sexual activity is a risk factor, since it favors the spreading of germs. Diabetes mellitus also contributes to a urinary tract infection because it reduces the functionality of the immune system and because the glucose that may be excreted in the urine serves as a nutrient for the bacteria. Another risk factor in women is the use of spermicides or pessaries for contraception. A previous antibiotic therapy can also promote the settlement of pathogenic germs by killing the physiological vaginal flora . A history of urinary tract infection is a significant risk factor, regardless of gender, as recurrences are common. The comparatively short urethra in women is also named as a favorable factor for the rise of pathogens. In current publications, however, the individual susceptibility to infection due to abnormalities in the immune system is weighted more heavily than this anatomical fact. Today, a low excretion of the protein uromodulin in children and women as well as certain isotypes of the T-cell receptor are associated with an increased frequency of urinary tract infections.

Classification and expansion

The division is made according to the organs involved into a lower or upper urinary tract infection or, depending on the potential severity of the course, into a complicated or uncomplicated infection.

The lower urinary tract infection affects the urethra and urinary bladder, in men also the prostate and seminal vesicles , and is differentiated from the upper urinary tract infection, in which the kidneys or ureters are involved. The upper one usually arises from a lower urinary tract infection.

Furthermore, a distinction is made between complicated and uncomplicated infections. Urinary tract infections are considered complicated in patients in whom

- the development is favored, for example by restricted defenses in the case of immunosuppression or diabetes mellitus,

- normally no urinary tract infections occur (children),

- Consequential damage is likely or particularly dangerous (pregnant women, elderly patients),

- an instrumental procedure has been performed on the urinary tract ( urinary catheter , cystoscopy , operation regardless of how long ago the operation was performed),

- an anatomical or neurological disorder of the bladder function or

- a malformation ( e.g. cyst kidneys ) or renal insufficiency are present.

Further divisions according to therapeutic aspects are the subdivision into community-acquired and nosocomial infections of the urinary tract, into acute and chronically recurrent urinary tract diseases and into symptomatic and asymptomatic urinary tract infections.

One speaks of a recurrent urinary tract infection (relapse) if the disease occurs twice within six months or three times within a year.

A particularly severe, potentially life-threatening course in which the bacteria get into the bloodstream is called urosepsis.

Pathogen spectrum

A distinction is made between those acquired in the hospital or in care facilities (so-called nosocomial) urinary tract infections and those acquired in the normal population (so-called outpatient ).

Outside of healthcare facilities, Escherichia coli , a gram-negative rod bacterium from the intestinal flora, is the leader with 70% . Other enterobacteria such as Klebsiella or Proteus species also occur. Also staphylococci (especially Staphylococcus saprophyticus ) or enterococci are not uncommon. Bacteria that are difficult to detect, such as Ureaplasma urealyticum or Mycoplasma hominis, can rarely occur. Additionally, Chlamydia trachomatis , which is mainly sexually transmitted, trigger a urinary tract infection. Another sexually transmitted germ is Neisseria gonorrhoeae , the causative agent of gonorrhea (gonorrhea). Overall, gram-negative pathogens predominate in around 86% of uncomplicated infections compared to gram-positive pathogens.

Escherichia coli is also common in infections acquired in healthcare facilities . However, Klebsiella, Proteus species and Pseudomonads occur more frequently here . The germs in health facilities are often resistant to several antibiotics. A resistance testing is necessary in these infections necessarily.

Viruses and protozoa such as Trichomonas vaginalis are described in the literature as rare pathogens causing urinary tract infections .

Clinical manifestations

Depending on how far the infection has risen in the urinary tract, the symptoms are varied. An involvement of the urethra itself causes pain when urinating ( dysuria ) or itching. These symptoms also occur with a bladder infection (cystitis). In addition, the flow of urine is often reduced. There may be a purulent ( pyuria ) or bloody ( macrohematuria ) admixture in the urine. It is also characterized by a frequent urge to urinate, but when the patient only passes small amounts of urine ( pollakiuria ). Typically, cystitis is less likely to have a fever. In acute renal pelvic inflammation, flank pain and fever are in the foreground, nausea and nausea can also occur. The clinical examination often shows pain when tapping the kidney bed . However, kidney involvement can also be completely without symptoms. For example, around 30% of bladder infections show symptom-free renal pelvic inflammation.

If the prostate is also affected in men , the patients often show a severe clinical picture with pain in the lower abdomen, in the perineal region and fever. In children, the elderly, or patients who have received a kidney transplant , the symptoms can be quite uncharacteristic. Even a severe clinical picture with kidney involvement can only express itself in fever or abdominal pain. In the elderly, confusion can be the only symptom. The distinction between upper and lower urinary tract infections is not possible based on the clinical symptoms.

In children, the symptoms vary depending on the age group. This can sometimes make diagnosis and adequate treatment more difficult. In the newborn , weight loss, poor drinking , jaundice , gray-pale discoloration of the skin, disorders of the central nervous system and sensitivity to touch can indicate an infection that has already risen to the kidney. Older infants often have a high fever. Diarrhea, vomiting and signs of meningitis are not uncommon . A urinary tract infection is the reason for 4–7% of all infants with fever of unknown cause. Small children often show typical symptoms with lower urinary tract infections, with pyelonephritis these are sometimes absent. In this case, stomach pain is often given as the only tangible symptom. Children up to the age of four or five are often unable to express the typical flank pain that indicates kidney involvement. Inadequately treated urinary tract infections can lead to a variety of complications, some of which can be serious, including the need for dialysis.

Investigation methods

After collecting the medical history ( anamnesis ), further diagnostics can be dispensed with in the case of typical symptoms of an uncomplicated urinary tract infection in women. Complicated infections or infections acquired in hospital require further investigation. The focus is on the detection of the pathogen. An examination of the urine using a test strip can detect white blood cells ( leukocytes ), nitrite and any red blood cells that may be present. Nitrite is produced by many of the bacteria that cause the infection (e.g. Escherichia coli ). However, the lack of nitrite does not rule out an infection. The white blood cells represent the immune system's response to the infection in the context of the inflammatory reaction . The leukocytes are also detectable in the urine sediment , from a number of ten white blood cells per μl the detection is considered clinically significant. The bacteria may also be directly visible during this microscopic examination. The presence of white blood cell casts indicates that the infection has already risen into the kidney and caused pyelonephritis.

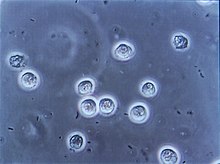

Another research method is urine culture, in which agar plates wetted with urine are used to grow bacteria. For this, the urine sample should be as midstream urine obtained by catheterization or to possible contamination by germs to avoid outside the urinary tract. The urine sample should be processed or cooled quickly to prevent false high values. Immersion agar plates are often used for the culture, in which the number of bacteria can be estimated semiquantitatively without further aids. Bacterial colonization can be assumed from a number of 10 5 colony-forming units per milliliter. This significant number of bacteria varies depending on the method of urine collection. It is only a relative quantity itself, and the likelihood of a urinary tract infection must be weighed in each individual case according to the symptoms and risk factors. In the case of typical symptoms, an infection can be assumed even if the number of colonies is lower. If two or more different types of germs appear in the culture, contamination of the sample is likely.

| Method of collecting urine | significant germ count |

|---|---|

| Midstream urine | 10 5 / ml |

| Bladder puncture | 10 2 / ml |

| Catheter urine | 10 2 -10 3 / ml |

A blood test can e.g. B. be useful if you have a fever . Elevated levels of CRP and an increase in white blood cells are signs of an inflammatory process. The removal of a blood culture serves to prove that the pathogen has passed into the bloodstream; the type of pathogen through the culture can also be determined. The culture must be taken before antibiotic treatment begins. An increased creatinine value indicates functional damage to the kidneys, which can be caused by a well-established infection. If this is the case, an ultrasound examination is also necessary in order to rule out obstructions in the urinary tract as the cause.

treatment

General therapy recommendations

- Elimination of anatomical or functional causes of urinary outflow or bladder emptying disorders

- Plenty of fluid intake to ensure adequate ("flushing out") diuresis

- Spasmoanalgesics for pain

- Possibly. Antipyretics

- Treatment of metabolic disorders such as diabetes mellitus

- Elimination of noxious substances of a chemical, physical or allergenic nature

Uncomplicated urinary tract infection

Urinary tract infections can be successfully treated with antibiotics. The goal is to eliminate the causative pathogen. Taking the antibiotic shortly before sleep is ideal in order to increase the concentration of the active substance in the bladder. In principle, it is also possible to limit therapy to non-drug measures (→ prevention ). Spontaneous healing can be expected in around half of the cases. The disadvantage of this method is that the patient has to endure the symptoms of the disease longer than with antibiotic therapy.

According to current urological guidelines, fosfomycin , nitrofurantoin and pivotmecillinam are the first choice if drug therapy is to be initiated . In particular, the slight damage to the intestinal flora and thus only a slight development of resistance were emphasized. After oral intake, nitrofurantoin is well absorbed and almost completely excreted in the urine. All three drugs are relatively inexpensive and well tolerated by the body's own bacterial flora. Serious side effects, including pneumonia, hepatitis or polyneuropathies , are extremely rare. The treatment takes place as part of a short therapy lasting between three and five days. Resistance is very rare. According to the German general medical association, trimethoprim is still recommended despite slightly increasing resistance rates.

The monopreparation trimethoprim as an inhibitor of bacterial folic acid metabolism and the combination preparation cotrimoxazole , which contains trimethoprim as well as the sulfonamide sulfamethoxazole , are no longer recommended as the drug of choice in the guidelines as a combination for the calculated therapy of uncomplicated urinary tract infection, especially since resistance is often evident. The sulfonamide content causes allergic skin reactions in around 4% of patients . In addition, hypoglycaemia and drug-induced skin damage ( Lyell's syndrome ) are possible. In the case of uncomplicated infection, there would be no increased effect of the combination preparation compared to trimethoprim alone. Fluoroquinolones can be used as a further reserve agent. There are also publications that see these as the first choice. They can also be used for three days of treatment, but they are more expensive than other first-line drugs. In addition, fluoroquinolones are not applicable to pregnant women.

As a general support measure, we recommend drinking at least one and a half liters per day. This flushes the germs out of the populated areas. According to the guidelines of the German Society for General Medicine, there are no reliable studies on the frequently used herbal preparations, teas and cranberry products that prove their effectiveness. With regard to cranberry preparations, however, a reduction in the adherence of bacteria to the urinary tract surfaces has been proven. A randomized clinical trial in Finland also showed a reduction in the incidence of symptoms of urinary tract infections by a fifth.

The usefulness of an examination to monitor the success of the therapy after symptomatic improvement is controversial between guidelines and textbooks. If there is no clinical improvement within 48 hours, it can be assumed that the drug has failed. In this case, you should switch to another agent.

Recurring uncomplicated urinary tract infection

In around 50% of patients, the infection recurs within a year. If the infection occurs within 14 days, it can be assumed that the pathogen will survive despite clinical improvement. In this case, treatment should be given with a different drug of first choice than the first treatment in order to counteract the development of resistance. In this case, therapy should be extended to ten days. If a urinary tract infection occurs more than 14 days after the first infection has clinically healed, a new infection can be assumed. A change of medication and an extension of the short-term therapy are not necessary.

If there is a connection between the recurring infections and sexual intercourse in a patient, prophylaxis with trimethoprim can help after sexual intercourse. Urination immediately after sexual intercourse counteracts the rise of pathogens. It is also mentioned in the literature to acidify the urine with L- methionine . The acidic environment of the urine offers poorer growth conditions for bacteria. So far, however, this method has only been confirmed as successful in a small study. Large studies are still pending, so the effect of methionine therapy has not been clearly established.

The S3 guideline for the treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infections, updated in 2017, recommends the use of medicinal products with nasturtiums and horseradish as herbal treatment options for frequently recurring cystitis . Numerous in-vitro studies show that even in small doses, the plant substances fight a large number of clinically relevant pathogens - including the most common pathogens causing urinary tract infections - and also have anti-inflammatory effects.

Complicated urinary tract infection

In the case of a complicated infection, a urine culture should be made before starting antibiotic therapy . Therapy should then be started with one of the drugs of first choice for at least seven days without evidence of a pathogen. As soon as the pathogen is detected by the culture, another antibiotic should be selected if necessary, which works optimally against the identified pathogen. If a treatable underlying disease is the cause of the complicated infection, it should be treated. Sometimes stenoses , strictures , prostate diseases or even previous interventions are the cause of this disease.

In the case of a urinary tract infection in pregnant women, the currently valid S3 guideline under the leadership of the German Society for Urology recommends that treatment with penicillin derivatives, cephalosporins or fosfomycin trometamol be considered.

Asymptomatic bacteriuria

If the urine test shows a significant number of bacteria, but no symptoms of a urinary tract infection, this is called asymptomatic bacteriuria . This is generally not considered to be in need of treatment, with the exception of certain risk groups. Pregnant women should, however, be treated, especially because of the risk of pyelonephritis, possibly also because of possible dangers for the child. After successful therapy, the urine should be checked for bacteria every month until delivery. Likewise, patients with immunosuppression , urinary flow obstructions or patients should be treated before TURP .

Pyelonephritis

If a urinary tract infection has progressed so far that it has led to kidney inflammation, cefpodoxime or quinolone antibiotics are the first choice , depending on the local resistance situation . They should be used for at least 5–14 days (depending on the drug and dosage). Cotrimoxazole should no longer be used for empirical therapy. Pregnant women, children and, depending on the clinical picture, other patients with complicated infections should be treated as inpatients in a hospital, in particular to enable initial intravenous therapy. If complications such as urinary outflow or abscess formation occur as a result of pyelonephritis , surgical therapy is indicated.

Urethritis

If an isolated inflammation of the urethra occurs, it is often caused by an infection with chlamydia , which can be detected with a smear. Therapy for a chlamydial infection is preferably a seven-day dose of doxycycline . Pregnant women should not be treated with this drug. You can be treated with a single dose of azithromycin or a cephalosporin. Since chlamydia is predominantly transmitted sexually, treatment of the sexual partner is absolutely necessary, even if the partner does not show any symptoms, as is the case with gonorrhea. One possible therapy is a single dose of ampicillin or amoxicillin . A seven-day treatment with tetracycline or doxycycline can also take place. Also gyrase inhibitors have been described as effective.

Viral urinary tract infections

Viral urinary tract infections are very rare. Adenoviruses , the cytomegalovirus and the BK virus from the polyomavirus family are described as triggering viruses . The latter in particular lead in many cases to a hemorrhagic form. The virus is detected via the polymerase chain reaction . Cidofovir is currently being discussed as a therapeutic approach .

prevention

Numerous measures are recommended in the medical literature for prevention and also to improve symptoms. It is advisable to drink a sufficient amount of around 2 liters per day if there are no previous illnesses that speak against it. In addition, the urge to urinate should not be suppressed. The bladder should be emptied as completely as possible when urinating. To reduce the infections after sexual intercourse, urination is recommended immediately afterwards. Constipation is suspected to promote urinary tract infections and should therefore be treated. In addition, hygiene in the intimate area should not be exaggerated, as this can destroy the normal bacterial flora. In the event of repeated infections in women, changing the method of contraception is recommended. In addition, people at risk should avoid wetness and hypothermia. However, the effectiveness of these strategies of non-drug prophylaxis has not yet been proven by valid studies.

To prevent recurrent urinary tract infections, vaccinations with inactivated germs (trade name "StroVac") are offered.

Medical history

In the second century AD, the Roman doctor Rufus of Ephesus described bladder infections as mostly quickly fatal. He also claimed that Hippocrates was able to cure inflammation of the kidneys by opening the kidney.

literature

Guidelines

- S3 guideline urinary tract infections in adult patients, uncomplicated bacterial community-acquired: epidemiology, diagnostics, therapy and management of the German Society for Urology (DGU). In: AWMF online (as of 2010)

- Guideline for burning sensation during urination of the German Society for General Medicine (DEGAM), available online ( pdf ), last accessed on February 28, 2013

- M. Grabe et al .: Guidelines on Urological Infections. ( Memento from June 17, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 1.0 MB) European Association of Urology, 2011

- S1 guideline urinary tract infection - diagnostic imaging of the Society for Pediatric Radiology (GPR). In: AWMF online (as of 2013)

Further publications

- M. Gimdt, E. Wandel, H. Köhler: Nephrology and high pressure . In Hendrik Lehnert , Karl Werdan (ed.): Internal medicine - essentials . 4th edition, Thieme, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-13-117294-0 .

- H. Huland, S. Conrad: Urinary tract infection . In: Richard Hautmann, Hartwig Huland: Urology . 3rd edition, Springer, Heidelberg 2006, ISBN 3-540-29923-8 , pp. 134-148.

- G. Weiss, H. Pall, M. Dierich: Infectious diseases through disease and fungi. In: Wolfgang Gerok et al. (Ed.): The internal medicine . Schattauer, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 3-7945-2222-2 , pp. 1338f.

- G. Stein, R. Fünfstück: Drug therapy of urinary tract infections . In: Der Internist , Springer, Berlin, Issue Volume 49, 6 / June 2008, pp. 747–755.

- Schmiemann, Guido et al .: Diagnosis of Urinary Tract Infection: A Systematic Review . In: Dtsch Arztebl Int . No. 107 (21) , 2010, pp. 361–367 ( Diagnosis of Urinary Tract Infection : A Systematic Review ).

- Marianne Abele-Horn: Antimicrobial Therapy. Decision support for the treatment and prophylaxis of infectious diseases. With the collaboration of Werner Heinz, Hartwig Klinker, Johann Schurz and August Stich, 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Peter Wiehl, Marburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-927219-14-4 , pp. 130-147.

Web links

- Urinary tract infections - kindergesundheit-info.de: independent information service of the Federal Center for Health Education (BZgA)

- Urinary tract infection - urologielehrbuch.de

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g Herbert Renz-Polster, Steffen Krautzig: Basic textbook internal medicine . Urban & Fischer, Munich 2008, ISBN 3-437-41053-9 , pp. 941-950.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i M. Gimdt, E. Wandel, H. Köhler: Nephrology and high pressure . In: Hendrik Lehnert, Karl Werdan (Ed.): Internal medicine - essentials . 4th edition, Thieme, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-13-117294-0 , pp. 530f.

- ↑ P. Gastmeier et al .: Prevalence of nosocomial infections in representative German hospitals. In: The Journal of hospital infection. Volume 38, Number 1, January 1998, pp. 37-49, ISSN 0195-6701 . PMID 9513067 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g G. Weiss, H. Pall, M. Dierich: Infectious diseases caused by fungi and bacteria. In: Wolfgang Gerok et al. (Ed.): The internal medicine . Schattauer, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 3-7945-2222-2 , pp. 1338f.

- ↑ a b c d e f H. Huland, S. Conrad: Urinary tract infection . In: Richard Hautmann, Hartwig Huland: Urology . Springer, 3rd edition, Heidelberg 2006, ISBN 3-540-29923-8 , pp. 134-148.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n guideline Burning when urinating of the German Society for General Medicine (DEGAM), available online ( as pdf ( memento of April 7, 2016 in the Internet Archive )), last accessed on 27 October 2015

- ↑ a b c d e f g G. Stein, R. Fünfstück: Drug therapy of urinary tract infections. In: The internist . Volume 49, Number 6, June 2008, pp. 747-755, ISSN 0020-9554 . doi: 10.1007 / s00108-008-2036-9 . PMID 18327562 .

- ↑ Acute cystitis - Clinical guidelines. Retrieved January 18, 2020 .

- ^ Marianne Abele-Horn: Antimicrobial Therapy. Decision support for the treatment and prophylaxis of infectious diseases. With the collaboration of Werner Heinz, Hartwig Klinker, Johann Schurz and August Stich, 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Peter Wiehl, Marburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-927219-14-4 , pp. 130-138 ( urinary tract infections ).

- ↑ Rolf Betz et al .: Urinary Tract Infections in Infancy and Childhood - Consensus Recommendations on Diagnostics, Therapy and Prophylaxis , Chemother J, 2006; 15: 163–171, accessed online as a pdf on May 31, 2008 ( memo of November 12, 2007 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ J. Scherberich: The consequences of insufficiently treated urinary tract infections . MMW Progress in Medicine Vol 157 (16), pp. 52–59 (2015)

- ^ Marianne Abele-Horn: Antimicrobial Therapy. Decision support for the treatment and prophylaxis of infectious diseases. With the collaboration of Werner Heinz, Hartwig Klinker, Johann Schurz and August Stich, 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Peter Wiehl, Marburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-927219-14-4 , p. 130.

- ↑ a b c d S3 guideline urinary tract infections in adult patients, uncomplicated bacterial community-acquired: epidemiology, diagnostics, therapy and management of the German Society for Urology (DGU). In: AWMF online (as of 2010)

- ^ D. Steinhilber, M. Schubert-Zsilavecz, HJ Roth: Medicinal Chemistry. 2nd edition, Deutscher Apotheker Verlag, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-7692-5002-2 , p. 549.

- ↑ P. Di Martino et al .: Reduction of Escherichia coli adherence to uroepithelial bladder cells after consumption of cranberry juice: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled cross-over trial. In: World Journal of Urology . Volume 24, Number 1, February 2006, pp. 21-27, ISSN 0724-4983 . doi: 10.1007 / s00345-005-0045-z . PMID 16397814 .

- ↑ T. Kontiokari et al .: Randomized trial of cranberry-lingonberry juice and Lactobacillus GG drink for the prevention of urinary tract infections in women. In: BMJ (Clinical research ed.). Volume 322, Number 7302, June 2001, p. 1571, ISSN 0959-8138 . PMID 11431298 . PMC 33514 (free full text).

- ↑ S3 guideline uncomplicated urinary tract infections - update 2017 (interdisciplinary S3 guideline "Epidemiology, diagnosis, therapy, prevention and management of uncomplicated, bacterial, community-acquired urinary tract infections in adult patients", AWMF register no. 043/044)

- ↑ A. Conrad et al .: Broad spectrum antibacterial activity of a mixture of isothiocyanates from nasturtium (Tropaeoli majoris herba) and horseradish (Armoraciae rusticanae radix). In: Drug Res 63: 65-68 (2013).

- ↑ V. Dufour et al .: The antibacterial properties of isothiocyanates. In: Microbiology 161: 229-243 (2015).

- ↑ A. Borges et al .: Antibacterial activity and mode of action of selected glucosinolates hydrolysis products against bacterial pathogens. In: J Food Sci Technol 52 (8): 4737-48 (2015).

- ^ A. Marzocco et al .: Anti-inflammatory activity of horseradisch (Armoracia rusticana) root extracts in LPS-stimulated macrophages. In: Food Func. 6 (12): 3778-88 (2015)

- ↑ H. Tran et al .: Nasturtium (Indian cress, Tropaeolum majus nanum) dually blocks the COX an LOX pathway in primary human immune cells. In: Phytomedicine 23: 611–620 (2016)

- ↑ ML Lee et al .: Benzyl isothiocyanate exhibits anti-inflammatory effects in murine macrophages and in mouse skin. In: J Mol Med 87: 1251-1261 (2009).

- ↑ Gerd Herold et al .: Internal Medicine , Cologne, 2011, pp. 599–605.

- ↑ DA Paduch: Viral lower urinary tract infections. In: Current urology reports. Volume 8, Number 4, July 2007, pp. 324-335, ISSN 1534-6285 . PMID 18519018 .

- ↑ German Society for Urology: Interdisciplinary S3 guideline on epidemiology, diagnostics, therapy, prevention and management of uncomplicated, bacterial urinary tract infections in adult patients. Retrieved February 20, 2019 .

- ↑ Jürgen Konert, Holger Dietrich: Illustrated history of urology . Springer, Berlin, 2004, ISBN 3-540-08771-0 , p. 21.