Helenenschacht

| Helenenschacht ( settlement / colony ) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Basic data | ||

| Pole. District , state | Oberpullendorf (OP), Burgenland | |

| Pole. local community | Ritzing | |

| Locality | Ritzing | |

| Coordinates | 47 ° 36 '41 " N , 16 ° 29' 47" E | |

| height | 460 m above sea level A. | |

| Post Code | 7323 | |

| prefix | + 43/02619 | |

| Statistical identification | ||

| Counting district / district | Ritzing (10820 000) | |

| Source: STAT : index of places ; BEV : GEONAM ; GIS-Bgld | ||

Helenenschacht ( Hungarian : Ilona akna ) is a settlement (colony) in the municipality of Ritzing in the Oberpullendorf district in Burgenland ( Austria ).

geography

Helenenschacht is located in the Ödenburg Mountains in Central Burgenland. The place is on the northern outskirts of Ritzing directly on the Austro-Hungarian border. The northern neighboring community of Ritzing in the area of Helenenschacht is the Ödenburg cadastral community of Brennberg .

Place name

The place owes its name to the mine shaft "Helenenschacht", which was located in Brennberg until around 1920/21, which was named after Helene Flandorfer from the mine operating family.

history

Before the birth of Christ, the area was part of the Celtic Kingdom of Noricum and belonged to the surroundings of the Celtic hill settlement Burg on the Schwarzenbacher Burgberg . Later under the Romans, today's Helenenschacht was located in the province of Pannonia .

From a geological point of view, mining in Ritzing belongs to the formerly important Brennberg coalfield ( Brennbergbánya ) near Ödenburg, today Sopron, which was also of particular relevance for the construction of the Wiener Neustädter Canal . In the 19th century, Brennberg and Ritzing were treated as two mines, the first of which belonged to the royal Hungarian free town of Ödenburg, the second to the Esterházy rule of Lackenbach . The coal obtained was called "hard coal" (as opposed to charcoal), but the area contains brown coal of various qualities ( lignite , lignite , semolina, cannel coal , shale coal , earth coal , differently designated depending on the source). The early as the middle of the 18th century Esterházyschem discovered owned coal seams were, until the sinking of the first combustion Berger hoistway ( Goblenzschacht ) in 1858, the open pit opened up; the first Ritzinger shaft ( Ignaz shaft ) was sacked in 1862 by the then tenants of the mine, the Ödenburg entrepreneurs Schwarz and Paul Flandorfer. Around 1870 a small workers' settlement was built, and in 1882 the Helenenschacht , which was named after Mrs. Helene Flandorfer (née Bauer), was sunk. Since 1888 the Brennberger Kohlenbergbau-Actien-Gesellschaft operated the Ritzinger and Brennberger mines together; around 1900 with 820 workers. In 1902 a tunnel was even cut from the Ritzinger Revier to the Sopronschacht , the main and central shaft of the Brennberger Revier; as a result, the Ignaz and Helenenschachts were shut down and only the conveyor line of the Helenenschacht was kept upright with a few miners. It was not until 1909, under the management of a stock corporation formed from the sugar factories in Siegendorf (Cinfalva), Draßburg (Darufalva) and Großzinkendorf (Nagycenk), that the Ritzingen mine received a new boom. At that time, 60 miner families were likely to have lived in the Helenenschacht colony. The winding tower of the Helenenschacht was encased in a brick building by Italian prisoners around 1914/15 for safety reasons and was given a special meaning again after the total collapse of the Sopron shaft in 1918. Around this time there was a cable car with which the coal mined in the Helenenschacht was transported to the main Brennberg plant. The two mines of Brennberg and Ritzing were separated when the border was drawn in 1921.

On May 8, 1923, the members of the Austrian National Council were informed that Hungarian mining law prevailed in the area of the Helenenschacht awarded to Austria , that Austrian miners were subject to Hungarian labor laws, that coal could be freely exported to Hungary and that Austria did not have the right to use its Granting mining rights to the territory. A parliamentary question was tabled and answered on the same day: Federal Chancellor Ignaz Seipel (1876–1932) told the deputies who were opposed to this regulation that the mine area had already been awarded to Hungary, but because of the protest on the part of Austria, the Ambassadors' Conference had considered the To determine the Helenenschacht settlement as belonging to Austria, subject to the assurance to be given by Austria in favor of Hungary that uniform management will be guaranteed in the Brennberg mining area. In order not to lose the area, the Austrian government complied with the demands of Hungary.

As a result of bilateral agreements, Austria recognized in 1928 that the operation of the "Barbara-Helenenschacht" (run by the Hungarian side) would remain an economic unit and that the Hungarian mining authorities (until 1963) would be responsible for the supervision and administration of the current and future expansion of the Austrian territory is subject to.

Austrians who became unemployed in the company did not receive any unemployment benefits, and especially after the Second World War, this regulation was an almost insurmountable obstacle for the health care of retired Austrian miners. At the state border, the iron curtain had become a massive obstacle from 1956 ( Hungarian popular uprising ). In order to ensure health insurance protection in Austria , a separate provision in Austrian social security law was created for you and your surviving dependents (widows, widowers), which still existed in 2017.

In accordance with the law, a gendarmerie post with four officers was set up on the Helenenschacht for the purpose of tightened security police; from October 1, 1932, it was responsible for monitoring the Helenenschacht and the municipality of Ritzing.

The Urikany-Zsilthaler Hungarian Coal Mining Company. from Fünfkirchen (Pécs) received mining and exploitation rights from the Austrian state until 1963, but closed the Helenenschacht as a mining shaft in 1930 and only used it as a weather shaft until 1936 . In 1946 an attempt was made in Ritzing to revive coal production with the help of a new open-cast mine. In 1955 the company had to be closed for good after the production in Brennberg had been stopped three years earlier.

In a report on a 1967 held Sonnwendfeier was mining village , which had never been visited since its inception by so many people at one time described as abandoned to decay. It was hoped that the colony would be revitalized by adapting the school building, which has been unused for years, as a training center for moped drivers .

In 1971 around 50 retirees were still spending their retirement years in Helenenschacht, which was still getting electricity from Hungary . In spring 1972, the Ritzing municipality decided to buy the 32 hectare area of the former coal mine from the Hungarian owners and to build a holiday colony on 200 plots . In 1974 the Helenenschacht area was developed with electricity and a 6.1 km long freight route network was created. In July 1977 Governor Theodor Kery visited the two old women who remain in their ancestral homes close to the Hungarian border, although structural change has swept this former mining settlement away . In order to alleviate loneliness, Kery handed over a sum of money to purchase televisions. In the summer of 1978, regular garbage disposal was announced for the new "Helenenschacht" settlement .

Of the factory settlement around the Helenenschacht , only the forest school (Helenenschacht 21 a), which opened on the site of a brick kiln on May 13, 1923 and closed in 1959, remained on Austrian soil . In the heyday of the settlement, more than 80 children attended school. Since then, it and the surrounding area have been used as a storage space for groups of children and young people, which is managed by the support association for the maintenance of the Helenenschacht forest school. - The Helenenschacht was filled in 1986 by order of the district administration , the dilapidated headframe was acquired by private parties in 1991, restored and kept accessible.

Attractions

- Helenenschacht (mine shaft. Built over with brick-sheathed headframe)

- Sonnensee Ritzing

- Wayside shrines

- Former iron curtain

- Inn

Economy and Infrastructure

The residents of Helenenschacht have to commute to work.

literature

- Social Democratic Party of Burgenland: Burgenland freedom . (From 1967.6: BF. The newspaper for Burgenland ). Digitized edition, 1922–2007. Association of Friends of the BF, Eisenstadt, ZDB -ID 2588385-9 .

- Eugen Schusteritsch : Oedenburg and the surrounding area. A home book . Published by the Oedenburg Committee of the sponsored town of Bad Wimpfen, Bad Wimpfen 1964, OBV .

- Manfred Wehdorn , Ute Georgeacopol-Winischhofer: Architectural monuments of technology and industry in Austria. Volume 1: Vienna, Lower Austria, Burgenland . Böhlau, Vienna / Graz (among others) 1984, ISBN 3-205-07202-2 .

- Nándor Becher: Brennbergbánya. 1753-1793-1953 . (German Hungarian). First edition. Brennbergi Kultúrális Egyesület, Sopron-Brennbergbánya 1993, OBV .

- Franz Zeltner: Brennberg from the point of view of - . In: oedenburgerland.de , accessed on September 21, 2013.

- Ferdinand Becher: The history of the Helenen settlement . From: -: Stories from the Brennberg past . Self-published, Brennberg 2001. In: oedenburgerland.de , 2011, accessed on September 21, 2013.

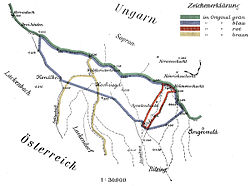

Helenenschacht and Brennberg around 1880 (map sheet of the Franzisco-Josephinische Landesaufnahme )

Helenenschacht, boundary stone ("M" for Magyarország ) from 1922 next to the transition to Hungary (2010)

Web links

- Homepage of the municipality of Ritzing

- Sonnensee Ritzing

- Helenenschacht forest school

- ( Page no longer available , search in web archives: History of the Helenenschacht winding tower at www.rajistan.com ) ([kunstland] -rajistan)

- Memorial stone at Helenenschacht - for the victims of the Iron Curtain

- Engineering office for building physics - Ing.Federica Hannel

- Ritzinger ink barrel

- Pyramids in Ritzing

Individual evidence

- ↑ 122. Ritzing. In: Austrian official calendar online . Verlag Österreich, Vienna 2002–, OBV .

- ↑ a b c August Ernst (historian): Burgenland in its Pannonian environment. Commemoration for August Ernst . Burgenland Research, Special Volume 7. Office of the Burgenland Provincial Government, Provincial Archives - Provincial Library, Eisenstadt 1984, ZDB -ID 1448585-0 , OBV , p. 179.

- ^ Judith Schöbel, Petra Schröck, Ulrike Steiner: The art monuments of the political district of Oberpullendorf . Berger, Horn 2005, ISBN 3-85028-402-6 , p. 598.

- ↑ Literature from: Albert Schedl, Josef Mauracher, Julia Rabeder: Complete bibliography 'Bergbau- / Haldenkataster' - published and unpublished archive and literature documents on the subject of mining, mining geology, deposit mineralogy and mining history. In: Reports of the Federal Geological Institute . No. 73. Vienna 2007.

- ↑ (Georg Carl Borromäus) Rumy (1780–1847): Hungary's hard coal wealth. In: G (ustav) F (ranz) Schreiner (Red.): Steiermärkische Zeitschrift. New series, fourth year, II. Issue. Verlag der Direction des Lesevereins am Joanneum, Graz 1837, ZDB -ID 802655-5 , pp. 118–121. - text online .

- ↑ Alexander von Matlekovits (also: Sándor Matlekovits, Sándor Matlekovics): The Kingdom of Hungary . Volume 2. Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1900, ÖNB .

- ^ A b Franz Zeltner: Brennberg from the point of view of - .

- ↑ a b Wehdorn: Baudenkmäler , p. 300. - Text online .

- ↑ parl. Inquiry dated May 8, 1923 (accessed June 12, 2017). P. 5540.

- ↑ Answer to the inquiry by Federal Chancellor Seipel (accessed June 12, 2017). Pp. 5551–5556 (Introduction by Member of Parliament Sailer on p. 5550).

- ↑ From the National Council. A sequel to the Burgenland border regulation . In: Burgenland freedom . III. Volume, No. 20/1923, p. 2, center left.

-

↑ Federal Law Gazette 1928/93 , therein in particular: Juridisches Protocol, regarding the operation of the Brennberg mine ,

B. H .: Where the Hungarian gendarmes came over. Country on the border. In: Arbeiter-Zeitung , No. 39/1928 (XLI. Year), February 8, 1928, p. 2 f. (Online at ANNO ). and

Hungary as a troublemaker . In: Burgenland freedom . VIII. Year, No. 6/1928, p. 1, top left. -

↑ Local news. (...) Ritzing. Need urges unity! In: Burgenland freedom . XII. Volume, no. 2/1932, p. 8, center left as well as

Die Bergarbeiter vom Helenenschacht. How the Hungarian People's Democracy Treats Austrian Workers . In: Burgenland freedom . XXII. Volume, No. 3/1952, p. 1, bottom center. - ↑ § 1 Z 10 of the inclusion ordinance according to § 9 of the General Social Insurance Act ASVG, ordinance of the Federal Minister for Social Administration of November 28, 1969 on the implementation of health insurance for those according to § 9 ASVG. Persons included in health insurance, Federal Law Gazette No. 420/1969 in the version of Federal Law Gazette II No. 439/2016, originally a regulation of the Federal Ministry for Social Administration of December 16, 1959 on the inclusion of further groups of people in health insurance; BGBl. No. 287/1959, p. 1783. (accessed June 10, 2017).

- ↑ Personnel changes in the gendarmerie . In: Burgenland freedom . XII. Volume, No. 38/1932, p. 4, bottom right.

- ↑ Training center for moped drivers . In: BF. The newspaper for Burgenland . XXXVII. Volume, No. 36/1967, p. 28, bottom right.

- ↑ A border community is building . In: BF. The newspaper for Burgenland . XLI. Volume, No. 13/1971, p. 16, center right.

- ↑ Ritzing builds a recreation center . In: BF. The newspaper for Burgenland . XLII. Volume, No. 44/1972, p. 8, top right.

- ↑ Ritzing buys "Helenenschacht" . In: BF. The newspaper for Burgenland . XLII. Volume, No. 9/1972, p. 10, top right.

- ↑ Ritzinger reservoir invites you to swim . In: BF. The newspaper for Burgenland . XLV. Volume, No. 27/1975, p. 17.

- ↑ Ritzing builds a reservoir . In: BF. The newspaper for Burgenland . XLII. Volume, No. 40/1972, p. 15, bottom right.

- ↑ The Ritzinger bathing lake is now officially open! In: BF. The newspaper for Burgenland . XLIX. Volume, No. 29/1979, p. 5.

- ↑ We noticed. (...) From Ritzing in the district (...) . In: BF. The newspaper for Burgenland . XLVII. Volume, No. 31/1977, p. 4, center right.

- ↑ Oberpullendorf. (...) Ritzing (...) . In: BF. The newspaper for Burgenland . XLVIII. Volume, No. 31/1978, p. 18, column 3.

- ^ Ritzing. (The forest school in the miners' colony) . In: Burgenland freedom . III. Volume, No. 20/1923, p. 3, bottom center.

- ↑ The history of the Helenen settlement

- ↑ (...) Ritzing. (…) A 40-member (…) . In: BF. The newspaper for Burgenland . XLVIII. Volume, No. 27/1978, p. 33, column 3.

- ^ Gerhard Bogner: The winding tower Helenenschacht . (Public attack). Helenenschacht 2010.

Remarks

- ↑ On the right the memorial stone at Helenenschacht and, in a cut, the associated building.

- ↑ The Republic of Austria refrained from exploring and extracting coal in the blue bordered area until 1963 . The Austrian mining authority only reserved the right to visit the mine for information and to inspect the mine maps . In the red-bordered part of the area - still available today in the digital cadastral map as Ried Kolonie Helenenschacht (33.09 ha) - the mining operations had to be granted increased security against any malicious or sabotage acts . Austria also undertook to reimburse the mining company for all damage which resulted from acts of sabotage and which occurred in the area under the supervision of its gendarmerie.

-

↑ Around 1800 an inheritance tunnel was cut at great expense . - See: Samuel Bredeczky (Ed.): Contributions to the topography of the Kingdom of Hungary . Volume 2. Camesinaische Buchhandlung, Vienna 1803, p. 104, text online .

The Ritzingen coal mine , a good half an hour from Brennberg , did not make any pleasant impressions around 1800 : The poor hut, the wet, dirty tunnel, which one only uses when necessary, the meager yield and the poor quality of the coal to be responsible for the fact that they are little known and sought after. The flotz consists for the most part, as far as I could see, of brown and charcoal, which, according to the unanimous testimonies of the fire workers, give little heat and a great deal of slag and ash. In the meantime, a better genus could be found, since they strike more into the depths and the structure as a whole has not yet been carried very far. - See: Samuel Bredeczky (Ed.): Contributions to the topography of the Kingdom of Hungary . Volume 2. Camesinaische Buchhandlung, Vienna 1803, p. 105 f., Text online .

- ↑ Around 1896 there were over 600, of which around 80%, around 500 men , suffered from ankylostomiasis ( hookworm infestation ) transmitted by horse droppings . - Central sheet for general health care. Organ of the Lower Rhine Association for Public Health Care . Volume 15 / 16.1896. Hager, Bonn 1896, ZDB -ID 217496-0 , p. 114.

- ↑ The Ignaz shaft was later filled in. - In: Wehdorn: Baudenkmäler , p. 300. - Text online .

- ↑ This law had already led to massive public criticism during its preparation in 1923. - See: H. S .: Helenenschacht . In: Burgenland freedom . III. Volume, No. 23/1923, p. 3, top left.

- ↑ Earnest B: the late 60s was the unusual power of the colony Helen shaft subject of a magazine program of ORF . In it, an elderly resident of the settlement informed the interviewer Heinz Fischer-Karwin (1915–1987) that the electricity bill would be paid by paying the required ( schilling ) amount to a lawyer in Vienna, who would then forward the sum to Hungary via the National Bank .

- ↑ Approx. 90 parcels with an average size of 420 m² each are, according to the digital cadastral map, still undeveloped, undeveloped plots (total size with traffic areas: about 4.7 ha ).

- ↑ The shaft has a circular cross-section with a diameter of 3.60 m and a depth of 328 m. - In: Wehdorn: Baudenkmäler , p. 300. - Text online .

- ↑ In 1920 the Neu-Hermes-Schacht was sunk on Hungarian soil and connected to the Helenenschacht about 600 meters to the northwest by a tunnel. After the Neu-Hermes shaft was rehabilitated after a partial collapse in 1949, the shaft was shut down in 1952 and its access sealed with a concrete ceiling. - See: Brennberg from the point of view of Franz Zeltner .

- ↑ Colony built in 1939 in order to shorten the daily journey for miners to the largest shaft in Brennberg (and at 700 m deepest shaft in Hungary), Szent István , which was sunk in the same year . Miners from this settlement were also employed in the Helenenschacht .