Vogt

The historical term Vogt - even Voigt or Fauth - comes from MHG. Vog (e) t , voit , woith , Vougt from ahd. Fogā̌t and ultimately lat. Advocate , lawyer, advocate, attorney ', literally, Hinzu- / Summoned' , from. It generally designates a manorial , often aristocratic official of the Middle Ages and early modern times . In French it corresponds to bailli , in English to bailiff or reeve .

function

The Vogt ruled and judged as a representative of a feudal ruler in a certain area in the name of the sovereign . He presided over the regional court and had to organize national defense. During the war he led the country's fiefdom .

The former area of control of a bailiff and his official seat (usually a sovereign castle ) are known as the bailiwick . A distinction was made among other reeves and Amtsvögte .

The legal principle represented by a bailiff is derived from the late Roman civil servant, the aforementioned advocatus , and from the Germanic Munt and is a protective relationship that also includes the right to violence and representation.

Reigned at the time of the Carolingians

Especially since the Carolingians of Vogt, a government official who as a deputy ecclesiastical dignitaries (z. B. was bishops or abbots ) or institutions in these worldly affairs, especially in secular courts represented (advocatus Ecclesiae) . Such representatives were prescribed for the church since late antiquity , as it was not supposed to carry out secular business. The Vogt therefore presented in the immunity area z. B. of a monastery or diocese was a kind of patron and usually also led its army (patronage). He also exercised the high level of jurisdiction in the bailiwick area ( Vogteigericht ). In the case of private monasteries , the owner of the monastery himself often held the Vogtamt. The patronage was soon transferred to the whole church and led several times to helping interventions (as under Henry III ), but on the other hand to the dispute over the supremacy between state and church that ran through the entire Middle Ages.

From 802, Charlemagne had bailiffs installed in monastic and episcopal immunities in the counties . In the 11th / 12th In the 19th century this office developed into a hereditary fief of the high nobility and was used by them as a form of power and territorial expansion. With the end of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation, the bailiwicks also lost their importance.

In the modern state, the idea of the umbrella bailiff has been incorporated into the constitutional principle of the supervision of churches and religious societies.

Church bailiffs

Foundations of the ecclesiastical bailiwick

The function of the bailiff was of particular importance in the ecclesiastical area. In the Middle Ages those items had to rely on an optionally armed protection, even not at all or only limited defenseless and feud capable were. In addition to the farmers, they were the clergy . Protection played an important role in the medieval world, as there was no state monopoly on the use of force and otherwise people would have been dependent on self-help. For ecclesiastical and theological reasons, the clergy were prohibited from exercising violence - and thus waging war and participating in physical and death sentences . The task of providing violent protection if necessary fell to the nobility , the class of "warriors".

During the early and high Middle Ages, therefore, many clergymen, churches, monasteries or foundations appointed aristocratic lay people as bailiffs, who represented them in secular matters (for example in court), administered the church property and granted them protection and protection. As early as the 9th century, the clergy had often no longer been able to hire bailiffs on short notice, as they were increasingly used to serve secular rulers and were subjected to stricter spiritual requirements. It was therefore necessary to have a permanent bond with a bailiff, who had to carry out the numerous tasks that were now arising. Since the middle of the 9th century, the bailiwicks have also been hereditary in many cases, whereby the aristocratic bailiffs often gained a strong position of power. Later, however, many clergymen tried to break away from the often oppressive position of power of the bailiffs and to reacquire bailiff rights, which was achieved above all by the great clergymen like the bishops since the 13th century.

Types of church bailiffs

With the bailiwick in the spiritual area, two different forms can be distinguished. The sphere of activity of a bailiff could extend to an entire spiritual institution, for example a monastery. This type of church bailiff was often referred to as "cast vogt". In the literature, the terms "Hauptvogt" or "Großvogt" are also used for the castvogt. The term “umbrella governor” usually also refers to such a governor of a spiritual institution. In addition to the governance of a spiritual institution itself, another characteristic of the church bailiwick was that only individual properties, for example a monastery, were governed. In this case, the rulership of the bailiff extended to the monastic property (including the associated landholders ) at a specific location or in a specific area. This type of governor is therefore often referred to in the literature as "local governor" or "district governor". Local or district bailiffs were particularly common in individual property complexes of a monastery that were further away from it.

Importance of the ecclesiastical bailiwick for the formation of territories

During the late Middle Ages, the bailiffs was often a comprehensive, not related to individual skills from the originally limited and consisting of individual rights competencies authority . In the course of this process, the spiritual landlords lost the power of rule to the bailiffs, and the bailiffs in particular were able to take control of the lower jurisdiction . Often the bailiffs were able to take over the military sovereignty , the right to taxes and compulsory service of the possessions or farmers they governed. In the course of this process, since the late Middle Ages, the bailiwick was often converted into more modern rulership rights as a rule of law and was absorbed into local jurisdiction, lower authority or sovereignty . Thus aristocratic bailiffs often succeeded in bringing monastic property under their control; the monasteries could only maintain the manorial rule over their estates owned by others. In the late Middle Ages, the bailiwick therefore formed an essential basis in many cases for the formation of the territories of noble rulers. In the wake of the Reformation , (cast) bailiffs who had become Evangelical succeeded in secularizing monasteries under their bailiwick and integrating them into their territory.

Governors

Since the 13th century, the term “Vogtei” was increasingly associated with an organization of offices in Germany. Vögte took on administrative tasks on behalf of secular rulers. They set taxes and collected them, they held courts and punished offenses.

Rudolf von Habsburg , Roman-German King 1273–1291, set up imperial bailiffs in order to administer the imperial territory directly under royal rule, above all the former Hohenstaufen property. On August 9, 1281, at the court assembly in Nuremberg, he formally stated that all gifts or disposals of imperial property made after the deposition of Frederick II (1245) were void, unless the majority of the electors approved the dispositions. He set up bailiffs who were supposed to find imperial estates appropriated without authorization and who acted as representatives of the king. These provincial bailiffs were an important instrument to revindicate the imperial property. Rudolf had the entire imperial estate divided into such administrative units and gave the governors extensive powers. This also ensured effective administration of the imperial property - something that had long existed in European monarchies such as France or England.

The best known of these Reichslandvogtei are the Landvogtei Schwaben (Upper and Lower Swabia ) and the Landvogtei Alsace ( Upper Alsace and Lower Alsace ), but also Breisgau , Ortenau , Speyergau , Sundgau and Wetterau . While most of the bailiffs were taken over by the sovereigns in the 15th century, the small bailiffs of Upper and Lower Swabia existed until the empire was dissolved in 1806.

see. List of governors in Alsace

Governors in the Lausitz

The medieval institution of the bailiwick lasted a particularly long time in the two margravates of Upper and Lower Lusatia . Introduced in the 14th century by the Brandenburg Ascanians , the bailiffs were also the highest officials of the sovereigns under the Bohemian kings (until 1620/35) and under the Saxon electors. At the end of the 17th century, the office lost its importance and became a mere title of the Saxon electoral prince (heir to the throne).

See also

- List of bailiffs in Upper Lusatia

- List of bailiffs in Lower Lusatia

- Bailiffs from Weida, Gera, Plauen and Greiz

Governor in Switzerland

In Switzerland, the title Landvogt appeared after 1415. There were numerous names for the function of the Landvogt: Kastlan, Obervogt, Gubernator and in the Italian-speaking areas Podestà , balivo, landfogto, capitano reggente or commissario. The bailiff was regent in the bailiffs instead of the lordly city or country canton of the old Confederation . He was in charge of the entire administration and appointed the local officials as long as local freedoms did not restrict his authority. This also included financial management, i. H. the collection of the gradient and fines as well as the accounting. Depending on the privileges of the Landvogtei, the Landvogt was a judge in lower and higher jurisdiction cases and presided over the regional court. He was also in command of the military contingent of the Landvogtei, executor of official orders and court orders.

The organization of the bailiffs was taken over by the Habsburg ruling organization. Rural bailiffs, which were ruled from several federal places, were referred to as common rule , where the ruling cantons set the bailiff in a fixed rotation. There were also numerous bailiffs in the territory of individual cantons.

The bailiff usually resided in a lordly castle within the bailiff, unless special privileges prevented him from staying in the bailiff, such as in the county of Uznach . Some of these castles still bear the name Landvogteischloss, such as the Landvogteischloss Baden and the Landvogteischloss Willisau .

In the old Confederation there were various forms of bailiwicks, in which the rights and duties of the office holder were more or less fixed by old freedoms and privileges of the bailiff. In particularly privileged areas, the subjects were even allowed to choose the bailiff himself, whereby the bailiff also appeared as a representative of the politically underage subjects. This particularly affected the so-called municipal cities or a few landscapes such as the Bernese Haslital .

The bailiff's income consisted mainly of the fines that he was allowed to collect as an executive, and to a lesser extent of fixed taxes from land or trade. A fixed salary was unknown. In some cantons, the bailiffs were actually auctioned - the bailiff then had to ensure that he was able to cover the expenses again within his term of office. In this context, the bailiffs of the common lords were considered particularly nefarious. However, there have been repeated efforts to prevent abuses through strict supervision. In any case, the office of bailiff was considered a lucrative post that was reserved only for families in the city or the countryside who were capable of regimentation.

The territorial boundaries of the bailiffs could not always be clearly drawn, since the boundaries of the official authority of the high and the lower jurisdiction as well as the exile did not always coincide. In addition, there were a number of minor rights that can no longer be represented geographically. Within the bailiffs, private individuals could also restrict the authority of the sovereign and thus also the bailiff, as they had acquired certain rights through purchase or had possessed them from ancient times. First and foremost, it was about monasteries and so-called barons , who only recognized the sovereign over themselves. They could have high or low jurisdiction and, more rarely, even the exile. In addition, there were the holders of the twing rights , who mainly held the lower and middle jurisdiction , but also private individuals who had fishing rights, hunting rights or the right to obtain lower gradients and fines. In reality, the authority of the sovereign, and thus also of the governor, was severely limited in most places and formed a confusing patchwork quilt that was difficult to survey even for contemporaries, but which corresponded to the zeitgeist of the ancien régime .

In the Helvetic Republic , the office of governor was abolished in 1798, as the term had many negative associations with the ancien régime. For this reason it was not reintroduced later. In its place in the canton of Bern the designation "Oberamtmann" was used, in other cantons other structures or other designations were created.

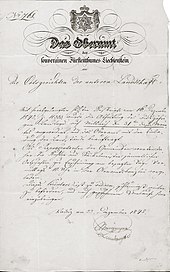

Land bailiffs in Liechtenstein

In the area of later Liechtenstein, from the 13th century the administrative and government tasks of the respective, mostly absent sovereigns were carried out by a deputy. Initially, titles such as “vogt” or “amman” or “amtmann” were used. From 1509 the term "Landvogt zu Vaduz" was used continuously. Between 1509 and 1848 there were about 45 governors in Liechtenstein. From 1848, during Johann Michael Menzinger's tenure , the office was renamed " Provincial Administrator ". This leaned on the official title of a deputy head, who was provisionally installed in the Frankfurt National Assembly in 1848 . In Liechtenstein, the office of provincial administrator was not abolished until 1921 when the new constitution of the Principality of Liechtenstein came into force. Since then, its tasks have been carried out by the government of the Principality of Liechtenstein, as the highest executive body of the state.

Vogtei as a name for jurisdiction

Since the end of the late Middle Ages, the term " Vogtei " ("Vogteilichkeit") has often been used synonymously with lower jurisdiction (lower authority). This use of the term “Vogtei” was common in the Franconian and Swabian regions. This also applied in cases where the lower authorities were not based on the older, ecclesiastical bailiwick, such as the estates of aristocratic or urban landlords. Similar or similar official positions were bailiff , village judge, Erbrichter , Fronbote , Gerichtskretscham, Greve , Meier , arbitrator, Scholze, guilt hot , Schulze, Vicar , Villicus , Woith (in alphabetical, not chronological order).

Burgvogt

A castle bailiff managed a castle, he was commissioned by the lord of the castle to exercise the duties and the lower jurisdiction in his absence. For example, a bailiff was installed at the Reichsburg Nuremberg.

Guardian, dike guard, alpine guard, forest guard

The medieval marrow cooperatives appointed guardians as their representatives.

In the coastal regions of the North and Baltic Seas, dyke bailiffs were responsible for the condition of the dikes and beach bailiffs were responsible for salvaging stranded shipments.

In many places in Switzerland, the person responsible for alpine operations is still called "Alpvogt", he hires the alpine staff, organizes the staffing of cattle, all work, accounts etc.

In the Hotzenwald there was the office of forest bailiff . In 1507, King Maximilian I issued an order comprising 17 articles, which was valid until the 18th century. The seat of the forest bailiff was initially Hauenstein Castle , later the bailiff's seat was moved to Waldshut-Tiengen in the forest bailiff's office.

In Dutch , the term Vlootvoogd ( German literally "Flottenvogt" ), originally from the 16th century, has survived into modern times . It is the popular name for the commander of an association of ships, i.e. a fleet commander .

Channel Islands

In Great Britain there are two areas that officially have the status of a Bailiwick ( English Bailiwick, French Bailliage ), the Channel Islands of Guernsey and Jersey . However, they are not headed by a Vogt, but as crown property they are directly subordinate to the British Crown.

Poland

In Poland , the title of Wójt ( Vogt ) continues to be used by the mayors of the rural communities .

Historically, the bailiffs were appointed by the sovereign or hereditary city heads or community leaders, mainly exercised by members of the nobility (szlachta). Until the 17th century, the village chief in German and Bohemian Silesia was called Woit . The Vogt of Warmia was the highest secular office holder in the prince-bishopric.

Literature (selection)

Essays

- Victor Attinger (Ed.): Historical-Biographical Lexicon of Switzerland . Volume 4: Güttingen - Milan. Administration of the historical-biographical lexicon of Switzerland, Neuchâtel 1927, p. 598f.

- Hanns H. Hofmann: Free farmers, free villages, protection and umbrella in the Principality of Ansbach. Studies on the genesis of statehood in Franconia from the 15th to 18th centuries . In: Journal for Bavarian State History. Vol. 23, 1960, ISSN 0044-2364 , pp. 195-327.

- Rudolf Hoke : Governor. In: Adalbert Erler , Ekkehard Kaufmann (Hrsg.): Concise dictionary for German legal history . Volume 2: Front door - Lippe. Schmidt, Berlin 1978, ISBN 3-503-00015-1 , pp. 1597-1599.

- H.-J. Schmidt: Vogt, Vogtei. In: Lexicon of the Middle Ages . Volume 8: City (Byzantine Empire) to Werl. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2009, ISBN 978-3-534-22804-1 , Sp. 1811-1814.

- Fred Schwind : Landvogt, -vogtei. In: Robert-Henri Bautier et al. (Ed.): Lexicon of the Middle Ages. Volume 5: Hiera means to Lucania. Artemis & Winkler, Munich et al. 1991, ISBN 3-7608-8905-0 , pp. 1681f.

- Fred Schwind: Reichslandvogt, Reichslandvogtei. In: Adalbert Erler, Ekkehard Kaufmann (Hrsg.): Concise dictionary for German legal history. Volume 4: Protonotarius Apostolicus - Code of Criminal Procedure. Schmidt, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-503-00015-1 .

Books

- Martin Clauss : The Untervogtei. Studies on representation in the church bailiwick in the context of the German constitutional history of the 11th and 12th centuries (= Bonn historical research, volume 61). Schmitt, Siegburg 2002, ISBN 3-87710-208-5 .

- Katharina Colberg: Imperial reform and imperial property in the late Middle Ages. University of Göttingen 1967 (Göttingen, dissertation of March 22, 1967).

- Hans-Georg Hofacker: The Swabian Reichslandvogteien in the late Middle Ages. Stuttgart 1980, ISBN 3-12-911570-6 .

- Hans Niese: Prokurationen and Landvogteien. A contribution to the history of imperial property management in the 13th century. Wagner, Innsbruck 1904 (also: dissertation, University of Strasbourg, 1904).

- Johannes Schneider : The German bailiwick and its influence on medieval Latin (= session reports of the German Academy of Sciences in Berlin. Class for languages, literature and art. Born 1964, Bd. 1, ZDB -ID 211653-4 ). Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1964.

- Ernst Schubert : King and Empire. Studies on the late medieval German constitutional history (= publications of the Max Planck Institute for History. Vol. 63). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1979, ISBN 3-525-35375-8 (also: Habilitation thesis, University of Erlangen-Nürnberg, 1974).

- Fred Schwind: The Landvogtei in the Wetterau. Studies on the rule and politics of the Hohenstaufen and late medieval kings (= writings of the Hessian State Office for Historical Regional Studies. Vol. 35). Elwert, Marburg 1972, ISBN 3-7708-0424-4 (also: Dissertation, University of Frankfurt am Main 1966).

- Thomas Simon: manorial rule and bailiwick. A structural analysis of late medieval and early modern rule formation (= studies on European legal history. Vol. 77). Klostermann Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1995, ISBN 3-465-02698-5 (Also: Dissertation, University of Freiburg (Breisgau), 1992).

Web links

- Waltraud Hörsch: Landvogt [Obervogt, Vogt]. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

Individual evidence

- ^ Max Döllner : History of the development of the city of Neustadt an der Aisch until 1933. Ph. CW Schmidt, Neustadt ad Aisch 1950. (New edition 1978 on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of the publishing house Ph. CW Schmidt Neustadt an der Aisch 1828-1978. ) P. 298– 301

- ↑ Landvogt - Historical Lexicon. Retrieved June 16, 2019 .

- ↑ Historical woordenboeken (Dutch) in the Woordenboek der Nederlandsche Taal of the Instituut voor de Nederlandse Taal , accessed on January 18, 2019.