Coalition governments in Germany

A coalition government is an alliance of parties that is formed in order to form a government and to provide parliamentary support on the basis of agreements in terms of content and personnel . These agreements, which are recorded in a coalition agreement after coalition negotiations , usually apply for one legislative period . The counterpart to the coalition government is a single government or a concentration government .

A coalition is likely to be formed if neither party wins an absolute majority in the parliamentary elections . However, a coalition does not necessarily have to achieve a parliamentary majority; it can also lead to a minority government of two or more partners.

History of the German coalitions at the national level

Coalitions in the German Empire 1871 to 1918

Since the Reichsleitung or the Reich Chancellor was always selected by the German Kaiser , government coalitions were not necessary. But there were alliances in parliament, such as the Bülow bloc of conservatives and national liberals. In view of the relatively large number of parties in the Reichstag - there were over sixteen in 1907 - and the different ideas, it was not possible to forge a lasting coalition that could have insisted on parliamentarization.

Coalitions in the Weimar Republic 1919 to 1933

The republic was initially supported by the so-called Weimar coalition , which lost its parliamentary majority as early as 1920. It consisted of the SPD , DDP and the center . The typical government coalition at that time, on the other hand, was an alliance between the center and the DDP, which was expanded sometimes to the left and sometimes to the right. Often it was a bourgeois minority government with parliamentary tolerance by the SPD.

A “grand coalition” in Weimar times was called an alliance from the SPD to the middle class and right through to the liberal DVP . This coalition existed twice: 1923 under Gustav Stresemann , 1928–1930 under Hermann Müller .

The two cabinets under Heinrich Brüning, 1930–1932 , were still bourgeois minority governments of the center and liberals, tolerated by the SPD and additionally supported by the Reich President with emergency ordinances. The cabinets of Franz von Papen and Kurt von Schleicher , on the other hand, consisted primarily of conservatives and “experts” and had no parliamentary basis (apart from the DNVP ). A coalition government was again the government of Adolf Hitler on January 30, 1933, consisting of the NSDAP and DNVP, although this only lasted until the DNVP dissolved itself a little later.

Coalitions in the Federal Republic of Germany

Coalitions 1949 to 1961

The first federal election (1949) was also called the last Weimar. But the CDU / CSU was soon able to integrate several small bourgeois parties (most recently the German Party , 1960) and clearly dominated the 1950s. Only the liberals of the FDP and the workers' party SPD remained .

Konrad Adenauer only formed a coalition with bourgeois parties. His first coalition from 1949, consisting of CDU / CSU, FDP and DP, only had a slim majority of three votes (he was missing two in the election for chancellor). Although the Union only lacked a mandate for an absolute majority in 1953 , Adenauer formed a coalition with the FDP, DP and GB / BHE to achieve a two-thirds majority. But the GB / BHE left the coalition in 1955, as did the larger part of the FDP in 1956 (the FDP split). After the federal elections in 1957, Adenauer retained the two DP ministers despite an absolute majority. It was only with the transfer of the DP ministers in 1960 that Adenauer's government formally became a sole government of the Union.

Coalitions from 1961 to 1969

The sixties with their four chancellors were very uneasy in terms of coalition politics, and all three possible coalitions were tried out.

With the 1961 election, Adenauer had to accept a coalition with the FDP, which ultimately insisted on his resignation. In the course of the SPIEGEL affair , Adenauer very seriously sounded out a coalition with the SPD, but then decided to continue the Christian-liberal coalition. In 1963 it was taken over by Adenauer's successor Ludwig Erhard .

In 1966, the Liberal ministers resigned from the cabinet because of differences of opinion over the 1967 federal budget. If necessary, the Union wanted to balance the budget through tax increases. Under Kurt Georg Kiesinger , the Christian Democrats have now entered into a coalition with the Social Democrats . A minority of the SPD thought of the FDP as a partner, but this coalition would only have had a very narrow majority.

Incidentally, the Union had tied the condition of the grand coalition with the SPD to introduce majority voting rights in order to make future coalitions unnecessary. But the SPD party congress of 1968 voted against changing the electoral system.

In 1969 the NPD did not come to the Bundestag despite different prognoses, and there was a slim majority of six members for a coalition of SPD and FDP. While Herbert Wehner would have preferred to continue the coalition with Kiesinger, the SPD chairman and Federal Foreign Minister Willy Brandt opted for the FDP.

Coalitions from 1969

Between 1969 and 1998 the FDP was continuously involved in the federal government, until 1982 with the SPD and then with the Union. In the 1960s, informal rules had emerged that served coalition peace. For example, the Liberals received more and more important ministerial posts than they would have been entitled to under the election results (and when they were given in 1949–1956 and 1961–1966). They were each involved with a key department in the major political areas: with the Foreign Office in the field of foreign affairs and security, with the Ministry of the Interior (since 1982: Justice) in internal and legal policy, with the Ministry of Finance or Economics in the economic or Budgetary policy.

With the Foreign Minister, the FDP had the most effective position next to the Federal Chancellor. The title of Deputy Chancellor was also more of symbolic weight. In 1966 the Christian Democrats could hardly refuse SPD chairman Brandt either. In 1969 FDP chairman Walter Scheel was moved to join the social-liberal coalition.

In 1998 the Greens were given the role of the smaller coalition partner. But besides the Foreign Minister / Deputy, there were ministries that were rather unimportant for them. Because they absolutely wanted the environmental department, they were in a bad negotiating position, and the social democrats at that time also had the mathematical possibility of a coalition with the FDP.

With the second grand coalition in the history of the Federal Republic of Germany, starting in 2005, a new chapter in coalition policy began. In general, the situation has become more confusing since reunification because Die Linke was able to establish itself as a parliamentary force. Furthermore, the Greens have opened up more to government participation and are also discussing the possibility of a coalition with the Union in principle. The 2005 Bundestag elections are special in terms of coalition politics because, for the first time after the legislative period from 1949 to 1953, no coalition based on the “one big party / one small party” scheme has a mathematical majority.

After the federal election in 2009 there was again the possibility of a coalition of CDU / CSU and FDP. Both parties had agreed in advance that they would prefer this option and formed a government at the end of October.

Coalitions in the GDR

A kind of coalition was staged in the GDR . The SED and other parties (e.g. the Eastern CDU ) and mass organizations (e.g. the trade union federation ) were united in the National Front . Since the National Front (actually the SED) determined who was allowed to put how many candidates on the unified list (for the elections), it was always clear before the election how big the individual parliamentary groups would be.

Although the GDR constitution required that the parties should participate in the government in proportion to their parliamentary mandates, in reality the SED received almost all ministerial posts. The " bloc parties " each had to be content with a deputy prime minister. Since these parties (like all other organizations) had to recognize the leading role of the SED and because there was no election competition, one cannot speak of a coalition in the democratic sense.

After the democratization of the GDR on the western model with the elections of March 1990 , there was a grand coalition of Christian Democrats, Social Democrats , Liberals and some other bourgeois parties ( de Maizière government ). The Liberals and later the SPD left this coalition in the summer of 1990, shortly before the end of the GDR.

Parties and coalitions in the Federal Republic of Germany

| Current coalitions in the countries | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

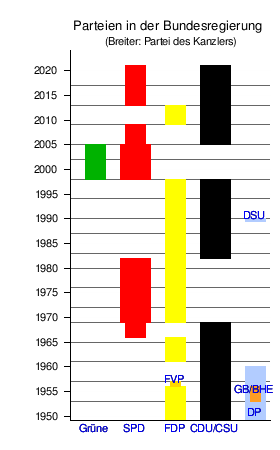

In the Federal Republic there have been black-yellow , black-red , social-liberal and red-green coalitions at the federal level since 1949 . In the early phase of the Federal Republic, the German party , the GB / BHE and the FDP split-off FVP were also involved in CDU-led coalitions. At the state level, the coalition landscape is more diverse. Traffic lights , red-red , red-red-green , black-green , black-red-green and Jamaica coalitions ruled or reigned here . Parties that are predominantly or exclusively regionally important also participate in state governments. Examples of this are the SSW in Schleswig-Holstein ( Albig cabinet ), the Free Voters in Bavaria ( Söder cabinet ) and the Schill party in Hamburg ( Senate von Beust I ).

The larger parties CDU, CSU and SPD are often more likely to seek a smaller coalition partner if they get a parliamentary majority with this partner than to form a large coalition . Therefore, large coalitions are rather rare and are often only entered into when a small coalition is mathematically or politically impossible. Well-known counterexamples are the Kiesinger / Brandt government at the federal level and the Bremen Senate between 1995 and 2007.

Of the original eight parliamentary groups in the first Bundestag from 1949, three remained in 1961: those of the Christian-Democratic Union and the Bavarian Christian-Social Union, that of the Social Democratic Party of Germany and that of the liberal Free Democratic Party. This constellation lasted until 1983, when the Greens moved into the Bundestag. In 1990 the PDS was added from the former GDR . From 2013 to 2017, the FDP was not represented in the Bundestag for the first time.

The traditional division into workers' parties ( SPD , KPD ) on the one hand and bourgeois parties ( CDU / CSU , FDP , DP ) on the other suggests a tendency towards a black-yellow coalition. This dichotomy is broken in individual policy areas and leaves room for other points of contact. Helmut Norpoth lined up the parties in an ideological continuum in which the Union was in the middle of economic policy, the SPD in cultural questions and the FDP in the question of ties to the West.

Gordon Smith, based on the three-party system between 1961 and 1983, depicted the relationships between these parties in a triangle. The Union and the FDP are therefore linked by bourgeois themes, corresponding to Norpoth's “economic order”, because property rights and the free market are meant. Between the SPD and the Union parties, corporatist issues mediate, i.e. the closeness to the trade unions or the social clerical roots of these parties. When it comes to corporatist issues , in which the liberals are weak, there is a permanent, hidden coalition, although a black-red coalition has only been formed once at the federal level. The social-liberal issues of the SPD and FDP concern the rights of the individual and are not explained further. Smith might think of family law issues or church policy.

Norpoth's Spectra deal with policy content from the 1950s that was hardly controversial in the following decade (Western ties, social market economy), and in social-liberal issues such as divorce or abortion regulations, the FDP cannot be clearly located to the left of the SPD. Some of these issues only became topical after 1969. In the crucial bread and butter topics, the political middle between the FDP and SPD clearly belongs to the CDU / CSU, as it corresponds to the distribution of seats in the Bundestag. Such a centralized situation does not necessarily have to pay off as a key position in coalition politics. In any case, the parties can be assumed to have links in terms of policy content for most of the theoretically possible coalitions.

CDU

After the Second World War, a Christian party was founded, which was able to redeem the non-denominational claim of the center and thus overcame a traditional German cleavage (cleavage refers to the religious division). Due to the large collection of Christian Democratic, Catholic-Social, conservative and nationally minded forces, the CDU offered a broad political spectrum - and thus points of contact with various coalition partners. For the Union it is most likely that the statement that a party can already represent a (permanent) coalition of different groups.

At the federal level, North Rhine-Westphalia's Prime Minister Karl Arnold (1947-56), Jakob Kaiser , Federal Minister and Chairman of the CDU Social Committee, and Bundestag President Eugen Gerstenmaier (1954-69), who had contacts from times of resistance, sympathized with the black-red option to the SPD. However, the predominant line of Konrad Adenauer led after 1949 at the federal level to an “anti-socialist” coalition policy excluding the SPD. In 1960, Adenauer saw the SPD as a Marxist class party that would steer Germany in the wrong direction of neutralism in terms of foreign policy.

As a party, however, the CDU lagged behind the SPD for a long time in terms of organizational structure and member support. Only in the opposition since 1969 and under the chairmanship of Helmut Kohl should that change fundamentally. Compared to the SPD, the CDU was less dependent on a “base” that made unpopular decisions such as B. the formation of a grand coalition sanctioned faster than the electorate.

CSU

The Christian-Social Union is on the one hand the Bavarian arm of the CDU, on the other hand it is an emphatically independent party with its own structures and party offices. According to Günter Müchler , the special alliance between the two Union parties is not a coalition , because it has no time limit and - despite internal competition - excludes electoral competition between the parties involved.

The joint parliamentary group forms the most important link between the two sister parties, but during the coalition negotiations the CSU acted like its own party again. In March 1961, Defense Minister Franz Josef Strauss became chairman of the CSU, who clearly opposed the SPD and, in the absence of an absolute majority, supported the FDP as a coalition partner. Only when the earlier problems with the FDP were repeated in the course of the 1960s and Strauss himself was disadvantaged by them did the CSU's interest in alternatives grow.

In Bavaria , the CSU had rarely formed a coalition with other parties. Until 1954, from 1962 to 2008 and 2013 to 2018 it achieved absolute majorities in the state parliament. It was only dependent on coalition partners from 1957 to 1962 and from 2008 to 2013 and since 2018. In the first case it formed a government with the FDP and GB / BHE, in the second with the FDP, and since 2018 with the Free Voters .

SPD

Due to the uncompromising opposition course of SPD chairmen Kurt Schumacher (until 1952) and Erich Ollenhauer (until 1964), for example, a coalition with the Christian Democrats at the federal level seemed unlikely. Although the Social Democrats shared with the Liberals their aversion to the nature and extent of integration with the West, it was above all economic and political differences of opinion that made a social-liberal federal government practically impossible. This did not change until 1959 when the Bad Godesberg program abandoned old Marxist positions and brought the SPD closer to the political center.

In terms of foreign policy, this realistic course was supported by a speech in the Bundestag in 1960, in which the deputy parliamentary group chairman Herbert Wehner finally gave up his neutralist plans for reunification, recognized the orientation towards the West and on top of that emphasized the commonality of the democratic parties. This meant that the three parties had come closer in general, even if the Union and FDP were still very reluctant to form a coalition with the Labor Party. The Social Democrats themselves could only wait to do better in the elections and at some point to be needed by one of the other parties as a majority funder. That happened in 1966 with the first grand coalition.

The Social Democrats see political reasons for a coalition with the Christian Democrats, since both parties are committed as people's parties similar to the political center. Usually, however, they prefer a small coalition with either the FDP or the Greens . With both there are similarities in the area of civil rights, but also conflict in the area of security (especially with the Greens). In addition, the Social Democrats, both as a workers' party and as a people's party, disagree with these two small parties (especially the FDP) on economic issues.

At the state level, the SPD is also forming a coalition with the democratic-socialist Left Party , which the left wing in particular tends to do.

FDP

In December 1948 the liberal forces united in Heppenheim to form the Free Democratic Party . But the different directions of liberalism continued to work. In 1952, at the Bad Ems party congress, there was almost a break between the southern German liberal democrats and the northern German national liberals, and only the latter's refusal to implement their “German program” prevented a possible split in the party.

The FDP alienated itself from Federal Chancellor Konrad Adenauer in the course of the 1950s , mainly because of different views on foreign policy. The conflict finally came to a head when Adenauer threatened the Free Democrats with the introduction of a majority vote . A coalition change in North Rhine-Westphalia in February 1956 ensured that Adenauer lost a two-thirds majority in the Federal Council . This new SPD-FDP coalition under Prime Minister Fritz Steinhoff was not a signal for “social liberalism” and was punished by voters just two years later; behind her stood the pure question of power of a threatened small party. Outraged by the decision in North Rhine-Westphalia, a third of the FDP members of the Bundestag and the FDP federal ministers left the party and finally found their way to the German party through the founding of a party and a merger . The FDP was split and no longer represented in the federal government, but Adenauer lacked a two-thirds majority in the Bundestag and Bundesrat, including for electoral reform.

The new leadership of the NRW Liberals , with the " Young Turks " Willi Weyer , Walter Scheel and Wolfgang Döring , came from the national camp, but wanted to place the FDP between the two major parties in terms of coalition politics. The Free Democrats, as an independent “third force”, should tip the scales . The Bundestag election campaign in 1957 was therefore conducted without a coalition statement from within the opposition. The party leader Reinhold Maier showed a certain inclination towards the Union.

The federal election in 1957 brought the FDP another loss of votes, the concept of the Third Force a severe blow and the Union an absolute majority. Together with the Social Democrats, the FDP was again in the opposition, but this did not lead to any rapprochement between the two. There remained the persistent differences in economic policy between the two parties; besides, one only knows government coalitions in Germany, but not opposition coalitions like in France (because of the different electoral system). The NRW liberals Scheel and Genscher, who would later determine the party's coalition policy, saw the time as not yet ripe for an SPD-FDP coalition.

In the absence of loyal, paying members, the Free Democrats were heavily dependent on donations, especially at the federal level, according to Kurt Körper. The particularly delicate financial situation for the FDP was also a reason for the great influence of the already strong NRW regional association and the treasurer Hans Wolfgang Rubin , who was also a board member of Gelsenkirchener Eisen und Metall. On the coalition question in 1968, taking these circumstances into account, Körper came to the conclusion that the FDP could neither afford the opposition nor a social-liberal coalition to carry out its lobbying activities. However, due to the need to strive for profiling, it remains a difficult partner for the Union.

The social-liberal coalition under SPD Chancellor Willy Brandt , which actually started in 1969, subsequently lost a number of FDP (and SPD) MPs who, among other things, disagreed with the New Ostpolitik. In 1970 Siegfried Zoglmann founded a " National Liberal Action ". The new elections of 1972 stabilized the FDP and the social-liberal coalition; However, the commonalities between the two partners were used up around 1976, after a reform of the criminal law. Franz Josef Strauss's candidacy for chancellor , whom the Liberals also rejected, extended the coalition to the "Bonn Wende" in 1982.

In terms of coalition politics, there were three to four groups in the FDP. The traditional wings were formed by the National Liberals with party and parliamentary group leader Erich Mende , who were also joined by one or the other right wing, and the mainly free-thinking old liberals from southern Germany. Both refused to work with the Social Democrats at the federal level, the former more strictly than the latter. As a rule, they formed a coalition with the CDU, albeit reluctantly, as Adenauer was too pragmatic for them on the national question. A small wing of left-wing liberals that only got stronger in and after the 1960s, on the other hand, was oriented towards the SPD. It included Secretary General Karl-Hermann Flach , who left politics in 1961 because of the "accident", Hildegard Hamm-Brücher from Munich and William Borm from Berlin .

The actual center of the party was provided by the former NRW Young Turks around Walter Scheel . She preferred to keep the coalition question open in order to give the FDP a key position between the big parties. Above all, the FDP should be free democratic and only then be a coalition partner of another party.

The first votes for the federal elections (and some state elections) show that the vast majority of FDP voters (over two thirds) tend towards the Christian Democrats. A coalition with the Social Democrats is usually only a second choice. The Liberals are particularly reluctant to take part in coalitions of the SPD and the Greens, as the competition between the two small participants in three-party coalitions is very fierce.

Alliance 90 / The Greens

Initially, the Greens did not want to enter into coalitions. However, the Realo wing soon sought coalitions with the SPD. The first coalition government with Green participation was the short-lived Hessian state government from 1985/86. Since 1990/91, red-green state governments have become more and more frequent, until the last one up until then was voted out in 2005 (in North Rhine-Westphalia). Since 2007 there has been a red-green coalition at state level in Bremen, others followed, for example in North Rhine-Westphalia. Up until 2008, the Greens only entered into coalitions above the municipal level under the SPD leadership, sometimes as a traffic light coalition including the FDP. From 2008 to 2010 there was the first black-green government coalition at the state level in Hamburg , under Ole von Beust (until August 2010) and Christoph Ahlhaus (until November 2010). In Saarland, the Greens participated for the first time in a Jamaica coalition at state level (under Peter Müller (2009–2011) and Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer (2011–2012)). Alliance 90 / The Greens now govern in nine coalitions in eight different constellations in the federal states.

As a result of the Baden-Württemberg state elections in 2011 , Winfried Kretschmann became the first member of Alliance 90 / The Greens to become Prime Minister of a German state.

The left

The roots of the party Die Linke go back to the Communist Party of Germany ; After 1945, this formed a coalition with the other parties, often at the state level, but not within the federal government. In 1946 she united in the Soviet occupation zone with the SPD to the Socialist Unity Party of Germany . In the only real coalition of the GDR - in 1990 after the free elections and before reunification - the party, renamed SED-PDS for a short time, was not represented. The PDS formed a coalition with the SPD in the state parliament of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania and in the Berlin House of Representatives.

On June 16, 2007, the PDS, renamed the Left Party, merged with the WASG in the newly formed Die Linke party . The Left is also forming a coalition with the SPD at state level, currently in Brandenburg.

As a result of the Thuringian state election in 2014 , a state government led by the Left Party, the Ramelow I cabinet , was formed for the first time .

German party

The conservative German party , which is mainly based in northern Germany, tied itself unilaterally to the CDU, with whose help it entered the Bundestag in 1957 and was accepted into the government by Adenauer despite his absolute majority. After most of their MPs had converted to the Union faction in several waves, the DP Bundestag group disbanded before the 1961 election.

GB / BHE

The All-German Bloc / Federation of Expellees and Disenfranchised (GB / BHE), founded in 1950, formed a coalition at state level with both the Union and the SPD. From 1953 to 1955 he was represented in the second government of Konrad Adenauer . Because of the increasing integration of the displaced, he did not get into the Bundestag in 1957 and failed in the long term in the federal states.

Extreme parties

As a rule, neither right-wing extremists (NPD, DVU, Republicans), right-wing populist (AfD) nor left-wing extremist parties (DKP, MLPD) are seen as capable or worthy of a coalition.

Further

At the state level, other parties succeed from time to time to move into the corresponding state parliaments. Occasionally there are coalitions with the participation of these parties. Examples of this are the Hamburg Senate of Beust I , in which the CDU formed a coalition with the FDP and the Schill Party (PRO) , and Voscherau III , in which the SPD entered into a coalition-like cooperation with the STATT party . At the municipal level, the SSW participates in some governments in Schleswig-Holstein . Free voter associations are also relevant at this level .

Distribution of ministerial posts

The distribution of the individual departments in the cabinet plays a prominent role in the coalition negotiations. Günter Norpoth has a formula for the quantitative distribution for the years 1949-82:

- y = 7.3 + 0.786 x.

Here y is the percentage of the number of ministers and x the percentage of those MPs who support the coalition (not the total number of MPs). So if a party contributed ten percent of the coalition seats, it received fifteen percent of the ministers .

With the additional consideration of more recent coalitions (1946-2005), Eric Linhart , Franz Urban Pappi and Ralf Schmitt also find a strong relationship between the relative seat share and ministerial share in a government, with a slightly stronger relationship for the federal level ( of 0.983) than for determine the country level ( from 0.910):

- y = 0.076 + 0.832 x (federal level)

- y = 0.083 + 0.808 x (country level).

In addition to the purely quantitative question of how many ministries a party has in a coalition, the qualitative question of which ministries a party holds is also important . This depends on the one hand on the strength of a party's interest in a ministry, but also on the strength of the interests of its coalition partners. The interest in certain ministries themselves can have different causes: parties can express certain programmatic priorities which they can implement better if they occupy the relevant ministry (e.g. the Greens at the Ministry of the Environment); In this way, however, they can also serve interest groups close to them (e.g. the CDU / CSU, the agricultural lobby , if it is the Minister of Agriculture).

The Foreign Ministry can be assumed to be of particular importance because, in addition to the Federal Chancellorship, it mostly guarantees a role at the international level and thus a certain amount of publicity. In fact, the Foreign Office has always been assigned to the smaller coalition partner since 1966. Furthermore, home affairs, justice, finance, defense and economics are classic or neoclassical and coveted departments. But this is not due to the budget of the ministries, because then defense, work and health should be the most desirable. Klaus von Beyme thinks of the size and complexity of the office, i.e. the large number of employees in the finance, home affairs, transport and defense departments.

A systematic analysis of which party occupies which ministry and how often is made more difficult by the fact that several business areas are often grouped under the umbrella of one ministry (e.g. currently the Federal Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Consumer Protection ). The composition of the ministries also varies over time as well as over the political level. Thus, for example in the Fifth Kohl cabinet , the division working with social order combined in Second Schröder cabinet , however, with the business economy . At the federal level, a foreign minister is common that does not exist at the level of the federal states; however, the federal states appoint a minister of education who is responsible for the school system and does not appear at the federal level due to the educational sovereignty of the federal states. The business areas that occur also vary between countries. In Rhineland-Palatinate , for example, you can often find the viticulture business field , fishing in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania or the current innovation business field in North Rhine-Westphalia . Even business every now and then sometimes performed explicitly on behalf of the Ministry, elsewhere, even though the relevant Minister has no jurisdiction (see., The division sport in the Cabinet cooking I and in the Cabinet Merkel I ).

If business areas that are often linked to one another are combined into overarching policy areas, the following findings can be gained for the parties at the state level: CDU and CSU particularly frequently occupy ministries in the fields of agriculture and culture , and relatively rarely environment and state planning , labor and social affairs, and economy and transport . The SPD has its focus in the areas of labor and social affairs as well as home affairs , it is represented below average in the areas of agriculture , economy and transport . It is noticeable that the FDP occupies the areas of economy and transport as well as justice ; it is rarely responsible for the federal government and Europe or agriculture . As expected, the Greens stand out for the environment and state planning as the most occupied policy area. They have never been involved in the home affairs area , initially in business and transport . The state chancelleries, some of which are designed as independent ministries, are usually occupied by the party that also provides the head of government. It is also noticeable that a party's involvement in the various political fields depends to a large extent on which party it forms a coalition with. In coalitions with the Union, for example, the Free Democrats relatively often occupy the area of the environment and state planning , but never in coalitions led by the SPD. There, in turn, they are much more involved in the judiciary than in Christian-liberal coalitions.

The longtime FDP Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher emphasizes in his memoirs the importance of both coalition partners assuming responsibility in the “three central areas of politics”. The partner who does not provide the Chancellor must occupy the Foreign Office and thus the most important individual department. Genscher contrasts the economy with the finance ministry, the justice system with the interior ministry. Otherwise, a coalition partner would be tempted to “run opposition within the coalition” for reasons of profiling.

This scheme has been followed since the first grand coalition (1966–1969) and also in subsequent coalitions with the FDP. Before that, the Liberals had acquired more, but less important, ministries. Under Chancellor Brandt, they were allowed to occupy both the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of the Interior for the first time. In the second Brandt cabinet, the scheme was fully implemented with the appointment of Hans Friderichs as Minister of Economics. The scheme is very advantageous for a small party because it assigns at least three key departments. This principle was not upheld under the red-green government of Gerhard Schröder. The grand coalition under Angela Merkel returned to this principle.

History and legal evaluation in Germany

In the 1960s, the question arose of the extent to which coalition agreements are permissible at all from a federal constitutional point of view. This interest is mainly due to the written agreements of the Christian liberal government of October 20, 1961. Like the coalition paper from the following year, it was published in newspapers, contrary to the original intention.

It caused great unrest, there were concerns that the Federal Republic of Germany could be governed by an organ not provided for in the Basic Law (GG), namely the coalition committee mentioned in the agreement . The parties and parliamentary groups involved committed themselves “to ensure that the parliamentary groups in the German Bundestag do not vote with changing majorities”. A coalition committee had to meet on the first working day of each week and included the parliamentary group chairmen, their deputies and the parliamentary managing directors. Experts from the political groups could participate on a case-by-case basis; other external advisors would require the consent of both sides. The vast majority of the agreement dealt with individual political issues, with Germany and foreign policy at the top. The coalition agreement was demanded by the FDP.

In order to allay the concerns raised by the coalition committee, the respective coalition partners tried after 1962 until the 1980s to avoid the impression of coalition committees. But it was clear that z. B. During the grand coalition, the Kressbronner Kreis represented such a regular coalition committee, named after the vacation spot of Federal Chancellor Kurt Georg Kiesinger in the summer of 1967. Federal Justice Minister Gustav Heinemann nevertheless maintained at the time that there was no institutionalized coalition committee. Usually the Federal Chancellor, the Federal Foreign Minister and the two parliamentary group leaders meet for a "meeting" on Tuesday .

In retrospect, Siegfried Heimann claimed that the SPD parliamentary group had degenerated into a “yes-man committee” and that parliament was even switched off as a controlling body. Wichard Woyke considered the coalition committee to be a kind of subsidiary government that ran government business without parliamentary responsibility. Andrea Schneider describes the Kressbronner Kreis as an informal place for the exchange of ideas between the party leaders, which was by no means a guarantee for the implementation of any bill.

Coalition agreements were secret treaties so that third parties could not invoke the agreement. Public coalition agreements as they exist today lack a certain raison d'être, because originally the government declaration for which the coalition partners are jointly responsible was supposed to fulfill this purpose.

In addition to procedural rules, coalition agreements relate to specific policy areas, more or less specifically. In practice, however, it is impossible to lay down government policy in a detailed contract, as it is, after all, four-year forward planning. This often leads to revisions of the agreement. With the change of power in 1969 (and similarly in 1982), the new partners wanted to take stock of the situation before going beyond a general coalition paper with negotiation results.

Constitutional commentators have taken the allegations against agreements and committees remarkably seriously. Roman Herzog justifies coalitions with the commitment of the Basic Law to the role of the parties (Art. 21 GG), whereby the coalition agreements are to be denied that they are legally binding because they are not enforceable. Adolf Schüle further explains that the coalition agreement cannot represent an objective law, if only because ought statements, public demonstrations and recognition by legal doctrine and courts are missing. In addition, the agreement was not drawn up by public bodies. The agreement could not be a business contract either, even if many lawyers and political scientists thought so. The principle of pacta sunt servanda (contracts must be adhered to) would be subject to the political reservation of rebus sic stantibus (provided that the conditions remain the same). Nevertheless, according to Schüle, the coalition agreement cannot be said to be a legal vacuum because such agreements would have political consequences.

In 1969, Federal Interior Minister Ernst Benda called it constitutionally in order for a coalition committee to take the decision to introduce a government bill. It would be more worrying if the coalition resolution decided on a draft law that has already been submitted to the Bundestag. That could lead to the desolation of parliamentary deliberations and would be constitutionally permissible, but unreasonable. The authority to issue guidelines is not restricted significantly more by a coalition than by the chancellor's dependence on his party. However, it is more difficult for the Chancellor to extend his influence to another party. Benda is more cautious about the departmental competence of the federal ministers, because if the minister concerned is not involved in the coalition committee, his influence on a law could be at risk.

The real question about the constitutionality of coalitions is what the coalition partners want to bring in return. In the 1961 agreement, the signatories undertook to encourage their MPs to vote. They cannot dispose of this, since Art. 38 GG guarantees the free mandate. The party and parliamentary group leaders cannot guarantee the success of their efforts, which is why it is not actionable.

literature

- Philipp Gassert, Hans Jörg Hennecke (Hrsg.): Coalitions in the Federal Republic. Education, management and crises from Adenauer to Merkel . Paderborn 2017 (Rhöndorfer Talks, Vol. 27).

- Eckhard Jesse: Coalition changes 1949 to 1994: Lessons for 1998? in: Journal for Parliamentary Issues . 29 (1998), pp. 460-477.

- Uwe Jun: Formation of coalitions in the German federal states. Theoretical considerations, documentation and analysis of the coalition formation at the state level since 1945 . Opladen 1994.

- Sabine Kropp, Roland Sturm: Coalitions and coalition agreements: theory, analysis and documentation . Opladen 1998. (PDF; 11.7 MB).

- Oskar Niedermayer: Possibilities of changing coalitions. On internal party anchoring of the existing coalition structure in the party system of the Federal Republic of Germany, in: Zeitschrift für Parliamentfragen 13 (1982), pp. 85–110.

- Detlef Nolte: Is the coalition theory at an end? A balance sheet after 25 years of coalition research . in: Political quarterly . 1988, pp. 231-246.

- Herbert Oberreuter: Coalition . in: Dieter Nohlen (Hrsg.): Piper's dictionary of politics . Volume I, Munich / Zurich 1985.

- Josef Anton Völk: Government coalitions at the federal level: Documentation and analysis of the coalition system from 1949 to 1987 . Regensburg 1988.

- Wichard Woyke: Coalition . in: Uwe Andresen, Wichard Woyke (Hrsg.): Concise dictionary of the political system of the Federal Republic of Germany . 2nd edition, Bonn 1995, p. 253.

Individual evidence

- ^ Helmut Norpoth: The German Federal Republic: Coalition Government at the Brink of Majority Rule, in: Eric C. Browne / John Dreijmanis (eds.): Government Coalitions in Western Democracies , New York / London 1982, p. 15.

- ^ Gordon Smith: Democracy in Western Germany: parties and politics in the Federal Republic , 3rd edition, Aldershot 1986 [1979], pp. 175/176.

- ^ Hans-Peter Schwarz: The statesman: 1952-1967 , Stuttgart 1991, pp. 80, 276, 599.

- ^ Günter Müchler: CDU / CSU. The Difficult Alliance, Munich 1976, p. 198.

- ↑ Kurt J. Körper: FDP balance sheet for the years 1960–1966. Does Germany need a liberal party , Cologne 1968 (Kölner Schriften zur Sozialwissenschaftlichenforschung 1), p. 42.

- ↑ Ibid., Pp. 64–66 / 73–75.

- ↑ Ibid., Pp. 246/249.

- ↑ Rule green. Retrieved January 14, 2019 .

- ^ Helmut Norpoth: The German Federal Republic: Coalition Government at the Brink of Majority Rule, in: Eric C. Browne / John Dreijmanis (eds.): Government Coalitions in Western Democracies , New York / London 1982, p. 23.

- ↑ Eric Linhart, Franz U. Pappi, Ralf Schmitt (2008): The proportional division of ministries in German coalition governments: the accepted norm or the exploitation of strategic advantages ?, in: Politische Vierteljahresschrift 49 (1), pp. 46–67.

- ↑ Klaus von Beyme: The political system of the Federal Republic of Germany. An introduction. Opladen / Wiesbaden 1999, p. 324.

- ^ Franz U. Pappi, Ralf Schmitt, Eric Linhart (2008): The distribution of ministries in the German state governments since the Second World War, in: Journal for Parliamentary Questions 39 (2), pp. 323–342.

- ↑ Hans-Dietrich Genscher: Memories , 2nd edition, Berlin 1995., pp. 110–111.

- ^ Die Zeit on February 2, 1962. Quoted from: Ossip K. Flechtheim u. a. (Ed.): Documents on party political development in Germany since 1945, Volume 8, Berlin 1970, p. 410. See there also the text (p. 408–410) and Heinemann's opinion (p. 417).

- ^ Heimann, Siegfried: Social Democratic Party of Germany, in: Richard Stöss [Hrsg.]: Party handbook. The parties of the Federal Republic of Germany 1945–1980. Pp. 2037, 2094.

- ↑ Wichard Woyke: Coalition, in: Uwe Andresen / Wichard Woyke (ed.): Concise dictionary of the political system of the Federal Republic of Germany , 2nd edition, Bonn 1995, p. 253.

- ↑ Andrea Schneider: The Art of Compromise, p. 96.

- ↑ Duke in Maunz-Dürig, Komm. Z. GG, Art. 63, Rn 9–12 ( Theodor Maunz / Dürig, Günther et al. (Eds.): Basic Law Commentary, o. O. o. J.). Adolf Schüle : coalition agreements in the light of constitutional law. A study on German teaching and practice , Tübingen 1964, pp. 59–61, 63–66, 70.

- ↑ Ernst Benda: Constitutional Problems of the Grand Coalition , in: Alois Rummel (Red.): The Grand Coalition 1966–1969. A critical inventory , Freudenstadt 1969, pp. 162–175, here pp. 162–165.