Maximilian I (Mexico)

Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian Joseph Maria of Austria (born July 6, 1832 in Schönbrunn Palace , then near Vienna , today 13th district ; † June 19, 1867 near Querétaro , Mexico) was the second eldest son of Archduke Franz Karl , a son of Emperor Franz I. , and Princess Sophie of Bavaria born. He was the next younger brother of Emperor Franz Joseph I from the House of Habsburg-Lothringen . During the Mexican wars of intervention he was in 1864 at the instigation of Emperor Napoleon III. enthroned by France as Emperor of Mexico . The political risk failed; Maximilian was captured by the legitimate government of President Benito Juárez in 1867 , sentenced to death by a court martial , and executed.

Childhood and youth

Ferdinand Maximilian was the second of four brothers. He received the usual education for an archduke . In addition to military training, his lessons consisted of foreign languages (French, Italian, English, Hungarian, Polish and Czech), philosophy, history and canon law. The prescribed drill program was anathema to him from a young age. He was considered to be imaginative and liked to paint and write. From an early age he was very interested in literature and history, especially those of his own family. Because of his charm he was very popular at the Viennese imperial court and also his mother Sophie's favorite. Nor did his parents worry about which area of responsibility the younger son would later take on. His relationship with his older brother Franz Joseph was friendly, although his brother observed him suspiciously as he got older, as his uncomplicated and friendly demeanor made him very popular with the Viennese population.

Even in childhood it became apparent that Ferdinand Maximilian could not handle money. While Brother Franz Joseph kept detailed records of his expenses, Maximilian kept buying books and pictures, which by far exceeded his finances. However, his mother helped him out every time, as she had a great understanding of the son's passion.

With his first apanage, which he received at the age of 17, he had a “summer house” built next to Schönbrunn Palace , which he named “ Maxing ” (a census district in official statistics and Vienna's Maxingstrasse are named after it).

During a stay in Portugal he fell in love with the beautiful Maria Amalia of Portugal . She was a perfect princess, wrote the young man in love at home. The two were as good as engaged when Maria Amalia suddenly died of pulmonary tuberculosis.

Italy

Maximilian was particularly interested in seafaring and made many long-distance trips (e.g. to Brazil ) on the kk frigate Elisabeth . In 1854, at the age of only 22 - as the emperor's younger brother and thus a member of the ruling house - he was appointed commander of the Imperial and Royal Navy (1854–1861), which he reorganized in the following years. In 1857 he married the Belgian Princess Charlotte and was appointed Governor General of Lombardy-Veneto . When Lombardy was lost in 1859 as a result of the Austrian defeat in the Battle of Solferino , Maximilian and Charlotte withdrew to the Miramare Castle near Trieste , which was built especially for them .

Mexico

The French Emperor Napoléon III. wanted to found a military and economic empire based on France in Mexico. He had already intervened with troops there since 1861 because Mexico (under its President Benito Juárez ) had expelled both the Spanish ambassador and the papal legate from the country. Benito Juárez had suspended payments of the $ 82 million debt demanded by Europeans for two years.

Assumption of power

In this situation Ferdinand Maximilian was proclaimed Emperor of Mexico on April 10, 1864 against the resistance of the Mexican people at the instigation of the French Emperor. Ferdinand Maximilian had previously made it a condition that the Mexican people wanted this. A Mexican delegation then brought him a rigged referendum that had been arranged by a junta of clericals and opponents of Juarez. Maximilian had to renounce his succession to the throne and inheritance claims in Austria under pressure from his brother. Ferdinand Maximilian believed that he could realize his dreams of a modern, liberal state in Mexico and therefore accepted the imperial crown on April 10, 1864 at Miramare Castle, despite the concerns of his family. The Habsburg took the French emperor's statements that the Mexican people wanted nothing more than a Habsburg emperor at face value.

Even the arrival of Maximilian and his wife did not lead to anything good. They were not received by dignitaries, but saw ragged beggars in the port of Veracruz who shouted more than sang while playing on their instruments. The triumphal arch had been overturned by a gust of wind, and the new imperial couple had to laboriously make their way through the mud. In Mexico City, he chose Chapultepec Castle as his imperial residence. The government palace, however, was desolate, gloomy and completely neglected, and the new emperor spent the first night on a pool table, as the mattresses were full of insects. Later he had the Paseo de la Reforma , then called Paseo de la Emperatriz ( Kaiserinallee ), set up as a connecting road between Chapultepec Castle and the city center. This avenue is an imitation of the Paris Champs-Élysées .

In Mexico, the Habsburgs found that all American states supported the Mexican President Juárez, who had been deposed by the French, because they saw Maximilian as undesirable European interference. Maximilian tried to broaden his power base by adopting the grandsons of the former Emperor Agustín de Iturbide and making them heir to the throne, as well as the appointment of ex-dictator Antonio López de Santa Anna as Imperial Marshal . After two years in Mexico, Maximilian passed a decree by which the followers of Juárez were considered robbers and could be killed without a court judgment. About 9000 people were murdered on the basis of this decree.

Disempowerment and death

After the end of the American Civil War , under pressure from the USA , the French had to withdraw their troops from Mexico under Marshal François-Achille Bazaine in 1866. After that, Emperor Maximilian could not hold his ground against the popular Juárez for long, as his calls for help in Europe also went unanswered. Maximilian's wife Charlotte even traveled personally to Europe to meet Napoleon III. and Pope Pius IX. asking for help - the latter only promised to pray for her and her husband. Thereupon Maximilian wanted to leave the country, but changed his mind after receiving a letter from his mother who asked him to stay.

With his last troops he finally holed up in the city of Querétaro, which fell after a siege on May 14, 1867. The decision was not made by attacking the besiegers, but by betrayal. Colonel Miguel López had opened the access to the city for the troops of the opposing general Mariano Escobedos (1826-1902) on the night of 14th to 15th May 1867 . Before that, however, he had given the emperor the opportunity to flee, which he refused.

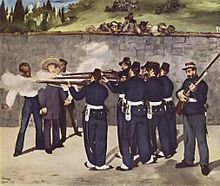

Maximilian was overthrown by a military court sentenced to death and for confirmation of the death sentence by the back came to power President Juarez on June 19, 1867 together with his generals Miguel Miramón and Tomás Mejía martial law in Tres Campanas, Querétaro shot . His wing adjutant , the German Colonel Felix Prinz zu Salm-Salm , was only able to narrowly avoid the same fate of death thanks to the personal commitment of his wife Agnes . Before the shooting, Maximilian assured the soldiers that they were only doing their duty, slipped them gold coins and asked them to aim carefully and spare his face so that his mother could identify his body.

After his shooting, Maximilian was brought to the Capuchin convent in Querétaro, where a military doctor and a gynecologist preserved the body . It failed so badly that another month was necessary. After long negotiations, Vice Admiral Wilhelm von Tegetthoff, who was sent to Mexico, was able to receive the corpse, which had been badly damaged by the transport, and finally bring it to Trieste on the Novara . From there Maximilian was transferred to Vienna in the court's gala funeral car, where - seven months after his execution - he was laid out in the Hofburg chamber chapel . He was buried in the Capuchin Crypt on January 18, 1868.

Charlotte survived Maximilian by 60 years, but went mad after his death. She lived first at Miramare, then at Bouchout Castle in Meise (Belgium) , where she died in 1927.

progeny

Maximilian and Charlotte had no children. Maximilian had already made a trip to South America in 1859/60, during which he contracted a sexually transmitted disease during one of his love affairs. It was thought that this made him sterile. However, in August 1866 one of his lovers, Concepción Sedano, the gardener's wife, gave birth to a boy who, after Maximilian's execution, was given to a wealthy landowner. This later brought him to France, where he called himself Sedano y Leguizano. He became a spy for Germany because of his immense debts, and when he was exposed, he posed as Maximilian's son - although the resemblance was considered great. Like his alleged father, he was shot in 1917 for spying.

Maximilian's valet Grill reports that Maximilian often received visits from ladies of the court. In Mexico, the emperor had the connecting door to his wife's apartments walled up, and now no more attempts were made to preserve the marital appearance.

reception

Conspiracy theory

According to ideas of conspiracy theory , Maximilian is said to have not been executed at all through a secret agreement with Juárez, but to have lived on in El Salvador until 1936 under the name of Justo Armas. For example, the writer Johann G. Lughofer claims to have found evidence of this.

art

Maximilian's favorite song is said to have been La Paloma by Sebastián de Yradier . According to legend, it was even said to have been played for his execution. However, recent studies seem to refute this assumption.

In any case, Maximilian's favorite song was played when his coffin was disembarked on the jetty at Miramare Castle. In memory of this sad event, the naval officers present decided that from now on La Paloma should never be played on Austrian warships again. This tradition is still kept by tradition-conscious Austrian sailors. It is also presented in the courses for obtaining a sailing license under "seamanship".

In 1867 Franz Liszt composed the piano piece “Marche Funèbre - En mémoire de Maximilien I, Empereur du Mexique. † June 19, 1867 ”. Motto: In magnis et voluisse sat est (propertius). The work has an interesting, open key plan, from F minor to F sharp major.

Édouard Manet painted " The shooting of Emperor Maximilian of Mexico " as a kind of reporter several times (1867 to 1869). In the first version (Museum Boston) the firing squad is still wearing Mexican uniforms, in the Mannheim version, which closes the series, guards in French uniform are shooting.

The struggle between Maximilian and Benito Juárez forms the historical background for Karl May's colportage novel " Waldröschen "; Maximilian's shooting is designed as a dramatic climax. In the five-volume revision of this work by Karl-May-Verlag, the title of vol. 55: Der dying Kaiser refers to these events.

Monuments

A statue of Maximilian stands today in the 13th district of Vienna in front of the entrance to the Schönbrunn Palace Park. The square in front of the Vienna Votive Church was formerly called "Maximilianplatz". In Bad Ischl , the Maximilianbrunnen on the Traun, built in 1868, commemorates him. Another statue of Maximilian is in Trieste . It was brought back to its original place, Piazza Venezia, in 2009 from the park of the Miramare Castle. Maximilian now “overlooks” part of the port of Trieste again. The Rostrata Columna, dedicated to him in 1876 in Maximilian Park in Pula , a work by Heinrich von Ferstel , was brought to Venice in 1919 as Italian spoils of war and is now, rededicated, on the edge of the Giardini pubblici.

Museums

In the Military History Museum in Vienna the fate of Maximilian is a special room. On display are including his death mask , the standard of the Imperial Mexican Hussar - Regiment (1865-1867) and a cartridge for officers of the cavalry of the Austro-Mexican Volunteer Brigade (1864-1867). In the museum's marine hall, Maximilian is honored as Commander in Chief of the Austro- Hungarian Navy . In addition to several portraits , including one by Georg Decker , there is also a model of the SMS Novara , which embarked the Archduke as emperor to Mexico and brought him back to Trieste as a corpse. In addition, a ship's cap and a naval officer's saber M.1850 from the personal belongings of Maximilian can be seen. His hat and fans, which his friend Nicola Bottacin kept, are exhibited in the Museo Bottacin in Padua .

Movie and TV

- Juarez , with Brian Aherne as Maximilian

- Vera Cruz , directed by Robert Aldrich , with George Macready as Maximilian

- Maximilian von Mexico , TV-FRG 1970, 3 parts, directed by Günter Gräwert , with Dieter Borsche as Maximilian

- Maximilian von Mexico - The Dream of Ruling , TV documentary ZDF 2014, directed by Franz Leopold Schmelzer

literature

- Francisco de Paula de Arrangoiz: México desde 1808 hasta 1867 (= Colección Sepan cuantos . Volume 82). 2nd Edition. Editorial Porrúa, SA, México 1968.

- Max Eggert: Maximilian and his artistic creations. In: Werner Kitlitschka u. a .: Maximilian of Mexico. 1832-1867. Enzenhofer, Vienna 1974, pp. 66–78, here p. 72.

- Werner Kitlitschka u. a .: Maximilian of Mexico. 1832-1867. Exhibition at Hardegg Castle from May 13 to November 17, 1974, Enzenhofer, Vienna 1974 (in it: Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian and the fine arts. Pp. 58–65; Franz Müllner: Johann Carl Fürst Khevenhüller-Metsch, an emperor's comrade in arms Maximilians von Mexico. Pp. 136–161, here p. 155; Elisabeth Springer: Maximilians Personality. Pp. 12–23, here p. 13).

- Ferdinand Anders : From Schönbrunn and Miramar to Mexico. Life and work of the Archduke Emperor Ferdinand Maximilian . Academic Printing and Publishing Company, Graz 2009, ISBN 978-3-201-01899-9 .

- Ferdinand Anders: The gardens of Maximilian (= series of publications of the district museum Hietzing. Volume 4). District Museum Hietzing, Vienna 1987.

- Johann Lubienski: The Maximilianeische state. Mexico 1861–1867. Constitution, administration and history of ideas (= research on European and comparative legal history. Volume 4). Böhlau, Vienna a. a. 1988, ISBN 3-205-05110-6 .

- Peter Burian : Maximilian, Emperor of Mexico. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 16, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-428-00197-4 , pp. 507-511 ( digitized version ).

- Friedrich Weissensteiner : reformers, republicans and rebels. The other house of Habsburg-Lorraine. Piper, Munich a. a. 1995, ISBN 3-492-11954-9 .

- Saúl Alcántara Onofre, Félix Alfonso Martínez Sánchez: Emperor Maximilian of Habsburg and his Gardens in Mexico (1864–1867). In: Supplement to Die Gartenkunst 20 (2/2008) = Habsburg. The House of Habsburg and garden art. ISBN 978-3-88462-271-1 , pp. 111-116.

- Thomas Edelmann: "Better things go wrong than not at all". Maximilian's Empire in Mexico 1864–1867 , in: Annual Report 2017 of the Heeresgeschichtliches Museum (Vienna 2018), ISBN 978-3-902551-81-8 , pp. 35–48.

- André Bénit: Legends , intrigues et médisances autour des "archidupes". Charlotte de Saxe-Cobourg-Gotha, princesse de Belgique / Maximilien de Habsbourg, archiduc d'Autriche. Récits historique et fictionnel , Bruxelles, Peter Lang, Éditions scientifiques internationales, 2020, 438 pages, ISBN 978-2-8076-1470-3 .

Graphic novel

- Marijan Pušavec, Zoran Smiljanić: Die Mexikaner, Vol. 1–5, Bahoe Books , Vienna 2018ff. (From the Slovenian by Erwin Köstler.)

Web links

- Literature by and about Maximilian I in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Maximilian I in the German Digital Library

- Empire of Mexico

- The painting Execution of Emperor Maximilian of Mexico ( Memento from February 26, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) by Édouard Manet

Individual evidence

- ^ Sigrid-Maria Großering : AEIOU: luck and misfortune in the Austrian imperial family. Amalthea-Verlag, Vienna 2007, ISBN 978-3-85002-633-8 .

- ↑ a b Konrad Kramar, Petra Stuiber: The quirky Habsburgs. Quirks and airs of an imperial house. Ueberreuter, Vienna 1999, ISBN 3-8000-3742-4 .

- ^ Ferdinand Maximilian of Austria Maximilian I, Archduke of Austria: From my life. Travel sketches, aphorisms, poems. Volume 6: Travel Sketches. Part 11. 2nd edition. Duncker and Humblot, Leipzig 1867.

- ^ Antonio Schmidt-Brentano: The KK or KuK Generality 1816-1918 ( Memento from October 4, 2013 in the Internet Archive ). Austrian State Archives, Vienna 2007, p. 130 (PDF).

- ↑ Renate Löschner: The death of Maximilian. In: Latin America - Memories in Tin. Ibero-American Institute, Berlin 1997, pp. 80-83, ISBN 3-9803291-3-5 .

- ↑ Maximilian of Mexico - The dream of ruling. Universum History on ORF on December 12, 2014

- ^ Konrad Ratz: Maximilian and Juárez. Backgrounds, documents and eyewitness reports. Volume 2: The moments of danger. “Querétaro Chronicle”. Akademische Druck- und Verlags-Anstalt, Graz 1998, ISBN 3-201-01679-9 , p. 389.

- ↑ Der Spiegel: The Adventurous Prince. Accessed August 10, 2015.

- ↑ Die Zeit: The Maximilian Files. Accessed August 10, 2015.

- ↑ Robert Seydel: The affair of the Habsburgs. Love rush and bed whispers of a dynasty. Ueberreuter, Vienna 2005, ISBN 3-8000-7038-3 , pp. 97-99.

- ↑ Sandra Weiss: Doubts about the shooting of the Emperor of Mexico. In: The Standard of March 24, 2001.

- ↑ Johann G. Lughofer: The emperor's new life. The case of Maximilian of Mexico . Ueberreuter, Vienna 2002, ISBN 3-8000-3874-9 .

- ^ Rüdiger Bloemeke: La Paloma. The song of the century . Voodoo-Verlag, Hamburg 2002, ISBN 3-00-015586-4 ( excerpt [accessed on September 25, 2011]).

- ^ Liselotte Popelka: Army History Museum Vienna. Publishing house Styria, Graz u. a. 1988, ISBN 3-222-11760-8 , p. 59.

- ^ Manfried Rauchsteiner , Manfred Litscher (Ed.): The Army History Museum in Vienna. Publishing house Styria, Graz u. a. 2000, ISBN 3-222-12834-0 , p. 55.

- ^ Army History Museum / Military History Institute (ed.): The Army History Museum in the Vienna Arsenal. Verlag Militaria , Vienna 2016, ISBN 978-3-902551-69-6 , p. 154.

- ↑ https://le-carnet-et-les-instants.net/2020/06/25/benit/

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Franz von Wimpffen |

Navy commander 1854–1860 |

Ludwig von Fautz |

| - |

Chief of the Marine Section 1860–1864 |

Ludwig von Fautz |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Maximilian I. |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Ferdinand Maximilian Joseph Maria of Austria |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Austrian Archduke, Emperor of Mexico |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 6, 1832 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Vienna |

| DATE OF DEATH | June 19, 1867 |

| Place of death | near Querétaro , Mexico |