Neuroleptic

A neuroleptic (plural neuroleptics ; from ancient Greek νεῦρον neũron , German 'nerve' , λῆψις lepsis , German 'seize' ) or antipsychotic is a drug from the group of psychotropic drugs that have a depressing ( sedating ) and antipsychotic ( fighting the loss of reality ) effect .

Areas of application

Neuroleptics are mainly used to treat delusions and hallucinations , such as those that can occur in the context of schizophrenia or mania .

In addition, they are also used as sedatives , for example for restlessness , fears or states of excitement . In this context, they are often used in old people's homes. In recent times, neuroleptics have been used increasingly for the following mental illnesses :

- in Tourette's syndrome and obsessive-compulsive disorders

- Depression or personality disorders

- Childhood ADHD and Fetal Alcohol Syndrome

- in autism against irritability and self-harming behavior

history

Beginnings

The starting point for the development of neuroleptics was the German dye industry at the end of the 19th century. At that time, BASF was producing chemical dyes that were soon used in histology . In certain dyes to put a antibiotic resistant effectiveness, for example, had the substance methylene blue , a phenothiazine - derivative against malaria . When using phenothiazine derivatives such as promethazine , a sedating and antihistaminergic effect was found. This should be an advantage in the case of shock and stress reactions caused by war and in operations . The additional vegetative (sympathetic and vagolytic) properties were called "artificial hibernation " and should be helpful in major operations. At the time, neuroleptic anesthesia was used together with opiates .

The first neuroleptic chlorpromazine

The first active ingredient to be marketed as an antipsychotic drug is chlorpromazine . It was first synthesized in France in 1950 during research on antihistaminic substances by the chemist Paul Charpentier at the Rhône-Poulenc company. However, its antipsychotic effect was not yet recognized at this point in time. In 1952, the French surgeon Henri Marie Laborit tried several antihistamines in search of an effective anesthetic . He noticed that these substances seemed to have a sedating and anxiolytic effect, especially chlorpromazine.

Between April 1951 and March 1952, 4,000 samples were sent to over 100 researchers in 9 countries. On October 13, 1951, the first article appeared in which chlorpromazine was mentioned publicly. Laborit reported on its success with the new substance in anesthesia. The two French psychiatrists Jean Delay and Pierre Deniker announced on May 26, 1952 that they had seen a calming effect on patients with mania. While chlorpromazine was used against many different disorders at the beginning, the most important indication later showed a specific effect against psychomotor restlessness, especially in schizophrenia.

From 1953 the chlorpromazine was marketed as Megaphen (Germany July 1, 1953) or Largactil in Europe, in 1955 it was launched in the USA under the name Thorazine . The term commonly used today "neuroleptic" was introduced in 1955 by Delay and Deniker. They observed that reserpine and chlorpromazine have very similar extrapyramidal side effects. The new drug was advertised in the US as a "chemical lobotomy ". The lobotomy was a common brain surgery technique at the time for treating a variety of mental and behavioral disorders. The use of chlorpromazine promised a comparable effect with the advantage that a purely drug treatment is non-invasive and reversible.

The neurophysiological effect of chlorpromazine was researched, based on which numerous other antipsychotic substances were discovered. The research led in 1957 to the accidental discovery of modern antidepressants and other active ingredients such as anxiolytics .

Influence on the treatment of mental disorders

Neuroleptics revolutionized the treatment of psychotic disorders . Before the introduction of neuroleptics, people suffering from acute psychosis had no symptomatic treatment method available. They were doused with cold showers or chained against their will, in the Middle Ages they were whipped or even burned at the stake. But even until the second half of the 20th century, many did not have adequate treatment options. Often the sick had to be admitted to a psychiatric clinic due to a lack of independence or the threat of endangering themselves and others and kept them there until the symptoms subsided over time. The only treatment options available there were protective measures such as deprivation of liberty or medicinal sedation in order to prevent the patients from harming themselves or third parties in their delusional state. In the United States , lobotomy was used to sedate the sick until the mid-20th century ; a neurosurgical operation in which the nerve pathways between the thalamus and frontal lobes and parts of the gray matter are severed.

With the introduction of neuroleptics, it was possible for the first time to combat the patient's symptoms in a more targeted manner, which reduced the duration of the pathological condition and thus the length of stay in the clinics. The use of neuroleptics quickly caught on, especially in Europe. In the United States, other treatments such as lobotomy and psychoanalysis were in use for a long time. Today the administration of neuroleptics is the standard method in industrialized countries for psychoses in need of treatment.

Neuroleptic threshold and potency concepts

In addition to the desired antipsychotic effect, the classic neuroleptics caused a number of side effects, including the so-called extrapyramidal syndrome . These are disorders of the movement processes that manifest themselves, for example, in the form of unsteady sitting or muscle stiffness, similar to those with Parkinson's disease. In his search for the optimal dosage of neuroleptics, the psychiatrist Hans-Joachim Haase found that the greater these extrapyramidal motor side effects, the stronger the antipsychotic effect. In 1961 he introduced the terms “neuroleptic threshold” and “neuroleptic potency”.

Haase defined the neuroleptic threshold as the minimum dose of an active ingredient at which measurable extrapyramidal motor side effects occur. As a measurement method, he developed a test of fine motor skills based on observation of handwriting and later known as the Haase threshold test. According to Haase, the neuroleptic threshold dose was also the minimum antipsychotically effective dose.

He defined neuroleptic potency as a measure of the effectiveness of a substance. The higher the neuroleptic potency of an active ingredient, the lower the dose that is required to reach the neuroleptic threshold.

After their publication, Haase's observations led to a massive reduction in the doses of neuroleptics administered in Europe and the USA.

For the later introduced second generation neuroleptics, the so-called atypical neuroleptics, the concepts of Haase lost their validity, since there is no longer a direct connection between the antipsychotic effect and the occurrence of extrapyramidal motor side effects.

Introduction of atypical neuroleptics

The introduction of neuroleptics represented a breakthrough, but in 30–40% of patients they were ineffective. With clozapine , a new generation of neuroleptics was introduced in 1971, the so-called atypical neuroleptics . They promised a comparable antipsychotic effect with little or no extrapyramidal motor side effects, and they also had an effect on the so-called negative symptoms of schizophrenia. They replaced the older drugs as the first choice and were often effective even in patients who did not respond to the previous drugs. To distinguish them from previous neuroleptics, these new active ingredients are called atypical neuroleptics or second generation neuroleptics (since 1994), while the old active ingredients are called typical, conventional or classic neuroleptics. Since then, a number of other atypical neuroleptics have been researched and brought to market.

pharmacology

Mechanism of action

The exact mechanism of action of neuroleptics is not fully understood and is the subject of current research. According to the common dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia, so-called positive symptoms such as hallucinations and delusional thoughts are caused by an increased concentration of the neurotransmitter dopamine in the mesolimbic tract of the brain .

Neuroleptics inhibit the signal transmission of dopamine in the brain through their antagonistic effect on postsynaptic D 2 receptors . The resulting inhibition of the mesolimbic pathways could therefore explain the antipsychotic effect.

The classic neuroleptics, also known as dopamine-antagonistic, have little specific effect in this regard, since their dopamine-inhibiting effect extends not only to the mesolimbic pathways but to the entire dopaminergic system. In addition to the desired antipsychotic effect, this also results in a number of side effects. In the nigrostriatal system, neuroleptics have a disruptive effect on physical movement sequences in which dopamine plays an important role. Classic neuroleptics also do not act on the so-called negative symptoms of schizophrenia, but can even make them worse, since, according to the dopamine hypothesis, they are caused by a reduced dopamine concentration in the mesocortical system of the brain.

The newer atypical neuroleptics have an antipsychotic effect comparable to the classic neuroleptics, but cause fewer extrapyramidal motor side effects and also act on the so-called negative symptoms of schizophrenia. These properties are attributed to the characteristics of their receptor binding profile, which can differ significantly depending on the active ingredient. For example, a more specific binding to the mesolimbic D 2 receptors is suspected. The interaction with receptors of other neurotransmitters such as serotonin , acetylcholine , histamine and norepinephrine could explain the additional effect on the negative symptoms.

Neuroleptics have a symptomatic effect, so they can not actually cure mental illnesses . Symptoms such as hallucinations , delusions or states of excitement can be suppressed at least for the duration of the drug treatment. This allows the patient to distance himself from the disease so that he can recognize his own condition as pathological.

unwanted effects

The possible undesirable effects depend heavily on the active ingredient and the dosage.

The undesirable effects are of a vegetative nature (hormonal and sexual disorders, muscle and movement disorders, pregnancy defects, body temperature disorders, etc.) and those of a psychological nature (sedative effects with increased risk of falling, depression , listlessness, emotional impoverishment, confusion, delirium and others Effects on the central nervous system with increased mortality in dementia patients).

Disruption of movement processes

One consequence of the inhibitory effect on the transmitter substance dopamine is the disruption of physical movement sequences, since dopamine is an essential factor. Since these disorders affect the extrapyramidal motor system , they are also summarized as extrapyramidal syndrome . They can be further divided into the following symptoms:

- Akathisia : Restlessness of movement that causes the person affected to constantly walk around or to perform movements that seem senseless, such as stepping on the spot or rocking the knee.

- Early dyskinesia : Involuntary movements through to spasmodic tension in muscles and muscle groups. Tongue and throat cramps are also possible .

- Parkinsonoid : Movement disorders that are similar in appearance to Parkinson's disease . Often there is muscle rigidity ( rigidity ) that makes the affected person's movements seem awkward and robot-like. A small, shuffling gait is often noticeable. Also dystonic disorders such as a torticollis occur. The so-called Haase threshold test, which uses handwriting to test fine motor skills, can be used for early detection of such disorders .

- Tardive Dyskinesia : In long-term treatment in up to 20% of all cases occur tardive dyskinesia, tardive dyskinesia also called on. These are movement disorders in the facial area (twitching, smacking and chewing movements) or hyperkinesis (involuntary movements) of the extremities. The severity of these disorders will depend on the dose and duration of neuroleptic treatment. In some cases, tardive dyskinesia does not resolve after discontinuation of the neuroleptic and remains for a lifetime. Stopping the neuroleptic can temporarily worsen the symptoms, but prevent further progress in the long term.

An anticholinergic such as Biperiden can counteract these symptoms and can therefore be administered as a supplement. Tardive dyskinesias do not respond to this, however.

Damage to the brain

Treatment with neuroleptics leads to a dose- and time-dependent remodeling of the structure of the brain with a shift in the ratio of gray to white matter and a reduction in the volume of various of its structures (neurodegeneration). A study carried out on monkeys found that their brain volume and weight decreased by about 10% after long-term administration of olanzapine and haloperidol , which are widely used in the treatment of psychosis .

Although schizophrenia as such is associated with a lower brain volume compared to healthy comparators, there are clear indications in numerous studies and findings that the drugs cause a further reduction in brain volume regardless of this. There are indications that the volume reduction goes hand in hand with a deterioration in cognitive abilities, such as poor orientation, deficits in verbal tasks, decreasing attention and a lower ability to abstract. These impairments are directly related to the level of the dose administered. Older recommendations that are based on doses that are now considered unnecessarily high and treatment periods that are too long are particularly problematic. Lower and time-limited dosages can therefore limit the damage. The most important German professional association for psychiatrists, the DGPPN , dealt with the problem, which has been gaining more and more attention in recent times, as part of its annual congress.

Other unwanted effects

Other possible undesirable effects are liver or kidney dysfunctions , cardiac arrhythmias (with a change in the QT time ), dysfunction of the pancreas , impaired sexuality and libido , weight gain, hormonal disorders (including in women: menstrual disorders ). Case-control studies also showed an increased risk of thromboembolism by about a third .

A number of neuroleptics show anticholinergic effects (such as chlorpromazine, thioridazine, fluphenazine, perazine, melperon and clozapine).

If there is an appropriate disposition , neuroleptics can be the trigger for so-called occasional seizures.

Rare (up to 0.4%), but potentially life-threatening side effects are the malignant neuroleptic syndrome with fever, muscle stiffness and rigidity, impaired consciousness, profuse sweating and accelerated breathing as well as disorders of the formation of white blood cells ( agranulocytosis ).

Certain neuroleptics may not be taken in the case of some changes in the blood count (e.g. clozapine), brain diseases, acute poisoning, certain heart diseases and severe liver and kidney damage. The use of neuroleptics together with alcohol or sedatives can lead to a dangerous increase in effectiveness. Tea, coffee, and other beverages containing caffeine can reduce the effects of neuroleptics. Neuroleptics can impair your ability to react. The ability to drive may be restricted and there may be hazards in the workplace (for example when operating machines).

Antipsychotics limit problem solving and learning. They have been linked to pituitary tumors and can lead to falls in old age. According to evaluations of several studies ( meta-analyzes ), the administration of antipsychotics in dementia patients leads to an increased risk of mortality compared to placebo administration.

Psychological side effects: Pharmacogenic anhedonia or dysphoria occurs in 10 - 60% of those treated with typical neuroleptics. These side effects also occur with atypicals, but less frequently.

Life expectancy

The influence of antipsychotics on life expectancy is controversial. Friedrich Wallburg, chairman of the German Society for Social Psychiatry (DGSP), explained in 2007: “Contrary to what is often assumed, neuroleptics do not increase the life expectancy of patients. Rather, it even sinks. "

However, a Finnish study from 2009 that included 66,881 schizophrenic patients in Finland and ran for eleven years (1996-2006) showed that patients with schizophrenic illness lived longer when they were treated with antipsychotic treatment.

Neuroleptic debate

There is also an ongoing debate within psychiatry about the advantages and disadvantages of neuroleptics, which has become known in the media as the neuroleptic debate. The German Society for Social Psychiatry has its own information page, which is updated with new information. The Soteria movement seeks to treat schizophrenia with little or no neuroleptics.

chemistry

Tricyclic neuroleptics (phenothiazines and thioxanthenes)

Tricyclic neuroleptics have been used therapeutically since the 1950s . They have a tricyclic phenothiazine ( phenothiazines : for example chlorpromazine , fluphenazine , levomepromazine , prothipendyl , perazine , promazine , thioridazine and triflupromazine ) or thioxanthene ring system ( thioxanthene : for example chlorprothixen and flupentixol ). The tricyclic promethazine was also the first therapeutically used antihistamine . Structurally, tricyclic neuroleptics are largely similar to tricyclic antidepressants . Differences in the pharmacological effect between the two substance classes are associated with a three-dimensional conformation of the tricyclic ring system that deviates from one another.

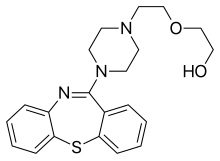

Dibenzepine

The newer tricyclic dibenzepines (e.g. clozapine , olanzapine , quetiapine and zotepine ) must be differentiated from the older tricyclic neuroleptics . They have a dibenzothiepin (zotepine), dibenzodiazepine (clozapine), thienobenzodiazepine (olanzapine) or a dibenzothiazepine ring system (quetiapine), which have a three-dimensional arrangement that differs from the classic tricyclic neuroleptics (pharmacological Effect are responsible.

Butyrophenones and diphenylbutylpiperidines

The butyrophenones (e.g. haloperidol , melperon , bromperidol and pipamperon ) are chemically characterized by a 1-phenyl-1-butanone building block. Based on haloperidol, numerous other neuroleptics have been developed, such as spiperone with a clearly recognizable structural relationship to the butyrophenones. The derived diphenylbutylpiperidines fluspirilen and pimozide are also used therapeutically .

Benzamides

The benzamides (active ingredients sulpiride and amisulpride ) occupy a special position , which apart from being neuroleptic have a certain mood-enhancing, activating effect.

Benzisoxazole derivatives, other substances

Structural parallels also exist between the atypicals risperidone and ziprasidone ; they can be viewed as distantly related to haloperidol. The newer aripiprazole has some similarities with the older substances. While risperidone has a particularly strong antipsychotic effect, ziprasidone still shows a norepinephrine -specific effect. Aripiprazole is a partial agonist at dopamine receptors and differs in this respect from all other neuroleptics currently approved in Germany.

Alkaloids

The pentacyclic Rauvolfia - alkaloid reserpine has in the treatment of schizophrenia only of historical significance.

Dosage forms

Neuroleptics are offered in different dosage forms . Oral ingestion in tablet form is most common , less often in liquid form as drops or juice. Liquid preparations are usually more expensive, but they have the advantage of better absorption in the gastrointestinal tract, and the intake can also be better controlled in uncooperative patients. In psychiatric clinics and in emergency medicine , neuroleptics are also administered intravenously, for example in order to bring about a faster onset of action in crisis situations.

For long-term therapy, so-called depot preparations exist, which are administered intramuscularly with a syringe . The term "depot" comes from the fact that the injected active ingredient is stored in the muscle tissue and from there is slowly released into the bloodstream. It is only necessary to refresh the dose after several weeks, when the depot is exhausted. This increases the generally low compliance of neuroleptic patients, since forgetting or unauthorized discontinuation of the medication is excluded for this period. In comparison to oral and intravenous administration, depot preparations have pharmacokinetic advantages such as better availability and, due to the slow, continuous release of the active ingredient in the blood, a more stable plasma level, which can reduce side effects.

As part of compulsory treatment , neuroleptics can, under certain conditions, be administered in psychiatric clinics against the patient's will. Injectable preparations are often used here, since certain preparations for oral ingestion can be spat out by uncooperative patients or hidden in the mouth.

Classification

High and low potent neuroleptics

Classical neuroleptics were previously divided into so-called high and low potency active ingredients with regard to their spectrum of action. Potency is a measure of the antipsychotic effectiveness of an active ingredient based on the amount. Each active ingredient has both an antipsychotic (combating the loss of reality) and a sedating (calming) active component, each of which has a different strength. The drop-out rates of drug treatment also differ due to the respective side effects. Antipsychotic neuroleptics are mainly antipsychotic and less sedating. They are particularly suitable for the treatment of so-called positive symptoms such as delusions and hallucinations . It is the other way around with sedating substances, they are mainly sedative and hardly antipsychotic. Therefore, they are given for symptoms such as restlessness, anxiety, sleep disorders and agitation. A combined intake is also possible. In the treatment of acute psychosis, for example, the daily administration of an antipsychotic substance is common, while a sedating preparation can also be taken if necessary. A meta-analysis from 2013 of 15 neuroleptics suggested a finer classification according to the respective indication and effectiveness.

The so-called equivalent dose can be used to classify the active ingredients into high and low potency. The equivalent dose is a measure of the antipsychotic effectiveness of a substance and is given using the chlorpromazine equivalent (CPZ) unit. Chlorpromazine, the first active ingredient used as a neuroleptic, was set as the reference value of 1. An active ingredient with a CPZ of 2 is twice as effective as chlorpromazine as an antipsychotic.

The concept of the equivalent dose is particularly important in connection with the typical neuroleptics, as these are similar in their mode of action and the side effects that occur. They differ mainly in their ratio of sedative to antipsychotic effects. The atypical neuroleptics differ significantly more in terms of their mode of action, side effects and areas of application, which means that a direct comparison using an equivalent dose becomes less important.

The classification of the active ingredients (according to Möller, 2001) is based on their chlorpromazine equivalent dose:

- low-potency neuroleptics (CPZi ≤ 1.0) These substances have no "antipsychotic" properties

- Examples: Promethazine, Levomepromazine, Thioridazine, Promazine

- moderately potent neuroleptics (CPZi = 1.0-10.0)

- Examples: chlorpromazine, perazine, zuclopenthixol

- highly potent neuroleptics (CPZi> 10.0)

- Examples: Perphenazine, Fluphenazine, Haloperidol, Benperidol

| Neuroleptic ( drug ) |

Substance class |

CPZ - equivalent X |

mean (- max. ) dose per day in mg |

Trade name (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Highly potent N .: | ||||

| Benperidol | Butyrophenone | 75 | 1.5–20 (- 40 ) | Glianimon |

| Haloperidol | Butyrophenone | 50 | 1.5–20 (- 100 ) | Haldol |

| Bromperidol | Butyrophenone | 50 | 5–20 (- 50 ) | Impromen |

| Flupentixol | Thioxanthene | 50 | 3–20 (- 60 ) | Fluanxol |

| Flus pirils | DPBP | 50 | 1.5-10 mg / week ( Max. ) | Imap |

| Olanzapine | Thienobenzodiazepine | 50 | 5–30 ( max. ) | Zyprexa |

| Pimozide | DPBP | 50 | 1–4 (- 16 ) | Orap |

| Risperidone | Benzisoxazole derivative | 50 | 2–8 (- 16 ) | Risperdal |

| Fluphenazine | Phenothiazine | 40 | 2.5-20 (- 40 ) | Lyogen |

| Trifluoperazine | Phenothiazine | 25th | 1–6 (- 20 ) | |

| Perphenazine | Phenothiazine | 15th | 4–24 (- 48 ) | Decentane |

| Middle Potent N .: | ||||

| Zuclopenthixol | Thioxanthene | 5 | 20-40 ( -80 ) | Clopixol |

| Clopenthixol | Thioxanthene | 2.5 | 25–150 (- 300 ) | |

| Chlorpromazine | Phenothiazine | 1 | 25–400 (- 800 ) | |

| Clozapine | Dibenzodiazepine | 1 | 12.5–450 (- 900 ) | Leponex |

| Melperon | Butyrophenone | 1 | 25–300 (- 600 ) | Eunerpan |

| Perazine | Phenothiazine | 1 | 75-600 (- 800 ) | Taxilane |

| Quetiapine | Dibenzothiazepine | 1 | 150–750 ( max. ) | Seroquel |

| Thioridazine | Phenothiazine | 1 | 25–300 (- 600 ) | |

| Low potency N .: | ||||

| Pipamperon | Butyrophenone | 0.8 | 40–360 ( max. ) | Dipiperone |

| Triflupromazine | Phenothiazine | 0.8 | 10–150 (- 600 ) | Psyquil |

| Chlorprothixes | Thioxanthene | 0.8 | 100–420 (- 800 ) | Truxal |

| Prothipendyl | Azaphenothiazine | 0.7 | 40–320 ( max. ) | Dominal |

| Levomepromazine | Phenothiazine | 0.5 | 25–300 (- 600 ) | Neurocil |

| Promazine | Phenothiazine | 0.5 | 25–150 (- 1,000 ) | Prazine |

| Promethazine | Phenothiazine | 0.5 | 50-300 (- 1200 ) | Atosil |

| Amisulpride | Benzamide | 0.2 | 50-1,200 ( max. ) | Solian |

| Sulpiride | Benzamide | 0.2 | 200-1600 (- 3200 ) | Dogmatically |

(Modified from Möller 2001, p. 243)

Typical and atypical neuroleptics

The first-generation neuroleptics, also known as typical neuroleptics , are ineffective in 30–40% of patients. In addition to the desired antipsychotic effect, they also caused a number of side effects, including the so-called extrapyramidal syndrome . These are disorders of the movement processes that manifest themselves, for example, in the form of unsteady sitting or muscle stiffness, similar to those with Parkinson's disease. The stronger a typical neuroleptic has an antipsychotic effect, the stronger these side effects are. In addition, the typical neuroleptics do not work against the so-called negative symptoms of schizophrenia and can even worsen them.

The newer, so-called atypical neuroleptics are characterized by the fact that they cause far less extrapyramidal motor side effects. They replaced the typical neuroleptics as the first choice and often work even in patients who do not respond to the previous drugs. They also have an effect on the so-called negative symptoms of schizophrenia. The atypical neuroleptics are assigned an overall more favorable side effect profile, which has a positive effect on the comparatively low compliance of neuroleptics patients. In return, however, they may have other, new side effects such as severe weight gain.

The differences between typical and atypical preparations have been examined in a large number of comparative studies. In 2009, a Germany-wide study funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research was launched, which compares frequently prescribed atypical neuroleptics in terms of effectiveness and side effect profile with classic neuroleptics and is still ongoing today.

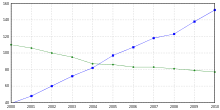

The cost-benefit ratio of modern atypical neuroleptics is criticized. The latest preparations are significantly more expensive than those that are available as generics due to expired patent protection. Atypical neuroleptics made up about half of all prescribed neuroleptics in Germany in 2011, but were responsible for 87% of sales. According to a drug report published by the Barmer GEK in 2011, two atypical neuroleptics were represented among the 20 most costly preparations with Seroquel and Zyprexa . The 2012 drug prescription report criticizes the high costs of some atypical preparations and is of the opinion that older, but similarly effective alternatives are available whose use would enable significant savings.

See also: List of Antipsychotics

Economical meaning

Neuroleptics are now the most frequently prescribed psychotropic drugs after antidepressants , and they even rank first in terms of sales. In the treatment of schizophrenia, they are now the drug of choice. But they are also widely used as sedatives, for example in the care of the elderly. About 30–40% of residents in old people's homes receive neuroleptics.

Preventive treatment

Previous study results have shown that long-term preventive treatment with neuroleptics in schizophrenic patients reduces the likelihood of relapse. However, according to another study, people with schizophrenia who are not treated with neuroleptics may experience fewer psychotic recurrences than those who take neuroleptics regularly. Internal factors may affect the likelihood of recurrence more than the reliability of taking medication.

literature

- Hans Bangen: History of the drug therapy of schizophrenia. Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-927408-82-4 .

- Möller u. a .: Psychopharmacotherapy. ISBN 3-17-014297-6 .

- O. Benkert, H. Hippius: Psychiatric pharmacotherapy. Springer, ISBN 3-540-58149-9 .

- Klaus Windgassen, Olaf Bick: Advances in neuroleptic schizophrenia treatment: second generation neuroleptics.

- Barbara Dieckmann, Margret Osterfeld, Nils Greeve: Weight gain under neuroleptics. In: Psychosocial Review. April 2004. Article about weight gain from neuroleptics and their consequences and risks.

- Mailman RB, Murthy V: Third generation antipsychotic drugs: partial agonism or receptor functional selectivity? . In: Curr. Pharm. Des. . 16, No. 5, 2010, pp. 488-501. PMID 19909227 . PMC 2958217 (free full text).

- Allen JA, Yost JM, Setola V, et al. : Discovery of β-arrestin-biased dopamine D2 ligands for probing signal transduction pathways essential for antipsychotic efficacy . In: Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA . 108, No. 45, 2011, pp. 18488-18493. doi : 10.1073 / pnas.1104807108 . PMID 22025698 . PMC 3215024 (free full text).

Web links

- Frank Meyer, Katrin Jahnsen, Gerd Glaeske: Pharmaceutical report 2005 on neuroleptics. Articles about neuroleptics and dyskinesias

- According to studies, Omega 3 works just as well against psychoses as neuroleptics:

- Review article: Tran instead of delusion .

- Full Study in English: Long-Chain Omega-3 Fatty Acids for Indicated Prevention of Psychotic Disorders

Individual evidence

- ↑ Roland Depner: Is it all a matter of nerves? How our nervous system works - or not . Schattauer, Stuttgart 2012, ISBN 978-3-7945-2887-5 , pp. 106 ( full text / preview in Google book search).

- ^ A b Gerd Laux, Otto Dietmaier: Psychopharmaka . Springer, Heidelberg 2009, ISBN 978-3-540-68288-2 , pp. 92 .

- ↑ a b Ulrich Schwabe, Dieter Paffrath: Drug Ordinance Report 2011 . 2011, ISBN 3-642-21991-8 , pp. 833 .

- ^ A b Peter Riederer, Gerd Laux, Walter Pöldinger: Neuro-Psychopharmaka - A Therapy Manual . 2nd Edition. tape 4 : Neuroleptics. Springer, 1998, ISBN 3-211-82943-1 , pp. 28 ( full text / preview in Google book search).

- ↑ a b Stefan Georg Schröder: Psychopathology of Dementia . Schattauer, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 978-3-7945-2151-7 , pp. 118 .

- ^ A b State Prevention Council North Rhine-Westphalia: Age - a risk? LIT Verlag, Münster 2005, ISBN 3-8258-8803-7 , p. 91 .

- ↑ T. Pringsheim, M. Pearce: Complications of antipsychotic therapy in children with tourette syndrome . PMID 20682197

- ↑ K Komossa, AM Depping, M Meyer, W Kissling, S. Leucht: Second-generation antipsychotics for obsessive compulsive disorder. PMID 21154394

- ↑ J Chen, K Gao, DE. Kemp: Second-generation antipsychotics in major depressive disorder: update and clinical perspective. PMID 21088586

- ↑ Klaus Schmeck, Susanne Schlueter-Müller: Personality disorders in adolescence . Springer, 2008, ISBN 3-540-20933-6 . P. 95.

- ↑ Nele Langosch: Do psychotropic drugs harm children and adolescents? Spektrum.de, October 9, 2015, accessed October 16, 2015 .

- ↑ David J. Posey, Kimberly A. Stigler, Craig A. Erickson, Christopher J. McDougle: Antipsychotics in the treatment of autism . PMC 2171144 (free full text)

- ↑ Hans Bangen: History of the drug therapy of schizophrenia. Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-927408-82-4 .

- ↑ Hans Bangen: History of the drug therapy of schizophrenia. Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-927408-82-4 , p. 92-

- ↑ a b c d e f g Frank Theisen, Helmut Remschmidt: Schizophrenia - Manuals of mental disorders in children and adolescents . 2011, ISBN 3-540-20946-8 , pp. 150 .

- ^ Christoph Lanzendorfer, Joachim Scholz: Psychopharmaka . Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg 1995, ISBN 978-3-642-57779-6 , pp. 118 .

- ↑ Elizabeth Höwler: Gerontopsychiatrische care . Schlütersche, Hannover 2004, ISBN 3-89993-411-3 , p. 15 .

- ^ A b Wolfgang Gaebel, Peter Falkai: Schizophrenia treatment guidelines . 2006, ISBN 3-7985-1493-3 , pp. 195 .

- ↑ a b c d Ulrich Hegerl: Neurophysiological investigations in psychiatry . 1998, ISBN 3-211-83171-1 , pp. 183 ( full text / preview in Google book search).

- ↑ a b c d Wolfgang Gaebel, Peter Falkai: Schizophrenia treatment guidelines . 2006, ISBN 3-7985-1493-3 , pp. 46 .

- ^ Hans-Joachim Haase, Paul Adriaan Jan Janssen: The action of neuroleptic drugs: a psychiatric, neurologic and pharmacological investigation. North Holland, Amsterdam 1965.

- ^ Edward Shorter : A historical dictionary of psychiatry. Oxford University Press, New York 2005, ISBN 0-19-517668-5 , p. 55.

- ↑ a b c d e Harald Schmidt, Claus-Jürgen Estler: Pharmacology and Toxicology . Schattauer, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-7945-2295-8 , pp. 229 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g Borwin Bandelow, Oliver Gruber, Peter Falkai: Short textbook psychiatry . Steinkopff, [Berlin] 2008, ISBN 978-3-7985-1835-3 , pp. 236 .

- ^ Frank Theisen, Helmut Remschmidt: Schizophrenia - Manuals of mental disorders in children and adolescents . 2011, ISBN 3-540-20946-8 , pp. 165 .

- ↑ a b Neel L. Burton: The Sense of Madness - Understanding Mental Disorders . Spektrum, Akad. Verl., Heidelberg 2011, ISBN 978-3-8274-2773-1 , pp. 63–65 ( full text / preview in Google Book Search).

- ^ A b c Wielant Machleidt, Manfred Bauer, Friedhelm Lamprecht, Hans K. Rose, Christa Rohde-Dachser: Psychiatry, Psychosomatics and Psychotherapy . Thieme, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-13-495607-1 , p. 333 ( full text / preview in Google book search).

- ↑ Torsten Kratz, Albert Diefenbacher: Psychopharmacotherapy in old age. Avoidance of drug interactions and polypharmacy. In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt. Volume 116, Issue 29 f. (July 22) 2019, pp. 508-517, p. 515.

- ↑ Stefan Schwab (Ed.): NeuroIntensiv . Springer-Medizin-Verl., Heidelberg 2012, ISBN 978-3-642-16910-6 , p. 286 .

- ^ Hans-Jürgen Möller: Therapy of mental illnesses . 2006, ISBN 3-13-117663-6 , pp. 231 .

- ^ Puri BK .: Brain tissue changes and antipsychotic medication . In: Expert Rev Neurother . 11, 2011, pp. 943-946. PMID 21721911 .

- ↑ KA Dorph-Petersen, J Pierri, J Perel, Z Sun, AR Sampson, D Lewis: The Influence of Chronic Exposure to Antipsychotic Medications on Brain size before and after Tissue Fixation: A Comparison of Haloperidol and Olanzapine in Macaque Monkeys. In: Neuropsychopharmacology , 2005, 30, pp. 1649-1661.

- ↑ Martina Lenzen-Schulte: Neuroleptics: When psychopills make the brain shrink. FAZ, January 26, 2015, accessed January 30, 2015 .

- ^ A b Frank Theisen, Helmut Remschmidt: Schizophrenia - Manuals of mental disorders in children and adolescents . 2011, ISBN 3-540-20946-8 , pp. 159 .

- ↑ C. Parker, C. Coupland, J. Hippisley-Cox: Antipsychotic drugs and risk of venous thromboembolism: nested case-control study . In: BMJ (British Medical Journal) . 341, 2010, p. C4245. PMID 20858909 .

- ↑ Torsten Kratz, Albert Diefenbacher: Psychopharmacotherapy in old age. Avoidance of drug interactions and polypharmacy. In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt. Volume 116, Issue 29 f. (July 22) 2019, pp. 508-517, p. 511.

- ↑ Wasserman JI, Barry RJ, Bradford L, Delva NJ, Beninger RJ .: Probabilistic classification and gambling in patients with schizophrenia receiving medication: comparison of risperidone, olanzapine, clozapine and typical antipsychotics. . In: Psychopharmacology (Berl). . 2012. PMID 22237855 .

- ^ Harris MS, Wiseman CL, Reilly JL, Keshavan MS, Sweeney JA .: Effects of risperidone on procedural learning in antipsychotic-naive first-episode schizophrenia. . In: Neuropsychopharmacology . 2009. PMID 18536701 .

- ↑ Wasserman JI, Barry RJ, Bradford L, Delva NJ, Beninger RJ .: Atypical antipsychotics and pituitary tumors: a pharmacovigilance study. . In: Pharmacotherapy . 2006. PMID 16716128 .

- ^ Schneider LS, Dagerman KS, Insel P: Risk of death with atypical antipsychotic drug treatment for dementia: meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials . In: JAMA . 294, No. 15, 2005, pp. 1934-1943. doi : 10.1001 / jama.294.15.1934 . PMID 16234500 .

- ↑ Ballard C, Waite L: The effectiveness of atypical antipsychotics for the treatment of aggression and psychosis in Alzheimer's disease . In: Cochrane Database Syst Rev . No. 1, 2006, p. CD003476. doi : 10.1002 / 14651858.CD003476.pub2 . PMID 16437455 .

- ↑ L. Voruganti, AG Awad: Neuroleptic dysphoria: towards a new synthesis . Psychopharmacology (2004) 171: 121-132

- ↑ Awad AG, Voruganti LNP: Neuroleptic dysphoria: revisiting the concept 50 years later . Acta Psychiatr. Scand 2005: 111 (Suppl. 427): 6-13.

- ↑ Martin Harrow, Cynthia A. Yonan, James R. Sands, Joanne Marengo: Depression in Schizophrenia: Are Neuroleptics, Akinesia or Anhedonia Involved? . Schizophrenia Bulletin, Vol. 20, No. 2, 1994.

- ^ Nev Jones: Antipsychotic Medications, Psychological Side Effects and Treatment Engagement Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 33: 492-493, 2012.

- ↑ Awad AG, Voruganti LNP: Neuroleptic dysphoria: revisiting the concept 50 years later . Acta Psychiatr. Scand 2005: 111 (Suppl. 427): 6-13.

- ↑ welt.de: Too many psycho pills reduce life expectancy , September 25, 2009.

- ↑ J. Tiihonen, J. Lönnqvist, K. Wahlbeck, T. Klaukka, L. Niskanen, A. Tanskanen, and J. Haukka, “11-year follow-up of mortality in patients with schizophrenia: a population-based cohort study (FIN11 study), ”Lancet, vol. 374, no. 9690, pp. 620-627, Aug. 2009. PMID 19595447 .

- ↑ Neuroleptic debate. German Society for Social Psychiatry , accessed on July 19, 2019 .

- ↑ Peter Riederer, Gerd Laux, Walter Pöldinger: Neuro-Psychopharmaka: A Therapy Manual / Volume 4: Neuroleptics . 2nd Edition. Springer Vienna, Vienna 1998, ISBN 3-211-82943-1 , p. 209 .

- ↑ Peter Riederer, Gerd Laux, Walter Pöldinger: Neuro-Psychopharmaka: A Therapy Manual / Volume 4: Neuroleptics . 2nd Edition. Springer Vienna, Vienna 1998, ISBN 978-3-7091-6458-7 , pp. 233 .

- ^ S. Leucht, A. Cipriani, L. Spineli, D. Mavridis, D. Orey, F. Richter, M. Samara, C. Barbui, RR Engel, JR Geddes, W. Kissling, MP Stapf, B. Lässig, G. Salanti, JM Davis: Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. In: Lancet. Volume 382, number 9896, September 2013, pp. 951-962, doi: 10.1016 / S0140-6736 (13) 60733-3 , PMID 23810019 .

- ↑ Wolfgang Gaebel, Peter Falkai: Schizophrenia treatment guidelines . 2006, ISBN 3-7985-1493-3 , pp. 48 .

- ^ Frank Theisen, Helmut Remschmidt: Schizophrenia - Manuals of mental disorders in children and adolescents . 2011, ISBN 3-540-20946-8 , pp. 165 .

- ^ T Stargardt, S Weinbrenner, R Busse, G Juckel, CA. Gericke: Effectiveness and cost of atypical versus typical antipsychotic treatment for schizophrenia in routine care . PMID 18509216

- ↑ John Geddes, Nick Freemantle, Paul Harrison, Paul Bebbington: Atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: systematic overview and meta-regression analysis . PMC 27538 (free full text)

- ↑ C. Stanniland, D. Taylor: Tolerability of atypical antipsychotics. In: Drug safety. Volume 22, Number 3, March 2000, pp. 195-214, PMID 10738844 . (Review).

- ^ B Luft, D Taylor: A review of atypical antipsychotic drugs versus conventional medication in schizophrenia . PMID 16925501

- ↑ S Leucht, G Pitschel-Walz, D Abraham, W. Kissling: Efficacy and extrapyramidal side-effects of the new antipsychotics olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and sertindole compared to conventional antipsychotics and placebo. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PMID 9988841

- ^ The Neuroleptic Strategy Study - NeSSy . Competence center for clinical studies Bremen.

- ^ Frank Theisen, Helmut Remschmidt: Schizophrenia - Manuals of mental disorders in children and adolescents . 2011, ISBN 3-540-20946-8 , pp. 162 .

- ↑ Jürgen Fritze: Psychopharmaceutical prescriptions: Results and comments on the 2011 drug prescription report . In: Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft Stuttgart (Hrsg.): Psychopharmakotherapie . tape 18 , no. 6 , 2011, p. 249 , doi : 10.1055 / s-0032-1313192 ( PDF ). PDF ( Memento of the original from December 16, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ BARMER GEK Pharmaceutical Report 2012 (PDF; 377 kB) Barmer GEK, accessed on January 25, 2013.

- ↑ Markus Grill: Drug Ordinance Report 2012: A third of all new pills are superfluous . Spiegel Online , accessed January 25, 2013.

- ↑ Jürgen Fritze: Psychopharmaceutical prescriptions: Results and comments on the 2011 drug prescription report . In: Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft Stuttgart (Hrsg.): Psychopharmakotherapie . tape 18 , no. 6 , 2011, p. 246 , doi : 10.1055 / s-0032-1313192 ( PDF ). PDF ( Memento of the original from December 16, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Peter Riederer, Gerd Laux, Walter Pöldinger: Neuro-Psychopharmaka - A Therapy Manual - Volume 4: Neuroleptics . 2nd Edition. 1998, ISBN 3-211-82943-1 , pp. 211 .

- ↑ Martin Harrow, Thomas H. Jobe: Factors involved in outcome and recovery in schizophrenia patients not on antipsychotic medications: a 15-year multifollow-up study. 2007, PMID 17502806 .