Politicos

The Politikos ( Greek Πολιτικός Politikós , Latin Politicus , German The Statesman ) is a late work by the Greek philosopher Plato , written in dialogue form . A fictional, literary conversation between an unnamed “stranger” from Elea and a young philosopher named Socrates, who is now called “ Socrates the Younger ”, was given by “ Socrates the Elder”, the famous teacher of Plato distinguish. Also present are Socrates the Elder and the mathematicians Theodoros of Cyrene and Theaetetus .

The two discussants set themselves the task of determining what constitutes a statesman and what the task of true statesmanship consists of. The stranger, far superior in expertise, directs the conversation. He explains to Socrates the younger the essence of statecraft. At the same time, the dialogue is an exercise in the methodically clean approach to a philosophical analysis.

The Dihairesis method is used to answer the question of what statecraft is . A general term - in this case “knowledge” - is subdivided into sub-terms until the exact definition of the term examined has been found. In this way, the interlocutors work out a proposed definition: statecraft is the knowledge of how to tend the herd of people. However, this definition turns out to be imprecise and must therefore be rejected.

Then the stranger chooses a new approach. First, he tells a myth that is meant to illustrate that the purpose of statesmanship as a shepherd's care for the herd of people is inadequate, for the shepherd's and herd-breeder's remit is broader than that of a politician. Then the stranger takes something familiar, the wool weaving, as a pattern to demonstrate the approach to defining the unknown, statecraft. In the " Weber parable " he differentiates weaving from all other arts with which it has similarities.

To be defined is the art of the true statesman who governs optimally, since he is guided by scientific principles and knowledge. Such a ruler sees himself as an educator of the citizens. His philosophical knowledge enables him to properly “weave together” opposing elements of human nature such as courage and prudence. This creates a balanced, harmonious mixture, and harmful one-sidedness is avoided. Under the guidance of the wise statesman, the state order is based on the right measure, on what is appropriate, which he knows thanks to his art of measuring. That is the ideal state; Constitutional provisions fixed in writing are then superfluous. But in the absence of such a statesman, the highest authority should be given to the laws introduced by prudent legislators. However, this is only the second-best solution, because a set of rules cannot replace the sovereign competence of an excellent decision-maker.

In modern research, the relationship between the politic and Plato's other state-theoretical writings, the Politeia and the Nomoi , is particularly controversial. The question is whether the philosopher has changed his mind on any essential points. Much attention is also paid to the problem of the contrast between the flexible, situation-appropriate discretionary decisions of a wise state leader and the rigid, in some cases counterproductive legal regulations. Legal norms prevent harmful arbitrariness on the part of those in power, but cannot always do justice to the reality of life.

Circumstances, place and time

In contrast to some other Platonic dialogues, the Politikos is not designed as a narrative by a reporter. The event is not embedded in a framework, but starts suddenly and is consistently reproduced in direct speech (“dramatic form”).

The Politikos is the third part of a trilogy , a group of three dialogues linked in terms of content and scenery that take place within two days. The first of these is Theaetetus , in which Socrates the Elder discusses epistemology with Theaetetus and Theodoros ; the younger Socrates listens in silence. The following day these men meet for a new discussion, which is presented in the dialogue of Sophistes . In addition, there is now another participant, the knowledgeable stranger from Elea, who takes on a central role. In English-language specialist literature it is usually called ES ("Eleatic Stranger"). Again, Socrates the Younger does not take part in the debate. His namesake is also holding back. The starting point this time is the definition of the term “ sophist ”. This is based on Plato's very negative understanding of sophistry, a controversial educational movement; it is defined as a certain art of deception. On the same day, the third dialogue, the politicos , takes place in the same circle as the Sophistes . Now that the nature of the sophist has been determined, the definitions of the statesman and the philosopher are still pending. Philosophy and statecraft, two serious sciences from the author's point of view, should be explored, correctly described and delimited from the sophistry, which Plato regards as a hoax. First the definition of the statesman is tackled; it forms the subject of the politicos . It is unclear whether Plato planned another dialogue dedicated to the peculiarity of the philosopher with the title Philosophos ; at least he didn't write it.

The three fictional dialogues of the trilogy take place in the spring of 399 BC. A short time before Socrates the Elder is sentenced to death and executed. The Theaetetus mentions that the charges against him have already been brought. The scene of the dialogues is the Palaistra - a practice area intended for wrestling matches - in a gymnasium . At that time the grammar schools served primarily for physical training; In addition, a Palaistra was also a social meeting place for young people. According to Plato, the elder Socrates liked to stay in places where there was an opportunity for fruitful conversations with young men and young people.

Attendees

Theodoros and the older Socrates only take part in the discussion briefly at the beginning of the Politos and then limit themselves to listening. It is unclear whether the older or the younger Socrates speaks the short final word. This time Theaetetus does not intervene at all, because now the younger Socrates is supposed to test his abilities and prove himself in dialogue with the stranger. The actual dialogue therefore only takes place between these two. The stranger expresses his views, while his young interlocutor limits himself for a long time to expressing agreement and asking questions.

Whether a certain historical person is hidden behind the mysterious stranger from Elea, whose name is kept secret, is unclear and controversial in research. The Eleate appears with great authority, his statements in the dialogues determine the course of the conversation and are received with approval. Hence, it is widely believed that he expresses Plato's own view. This seems to be supported by the fact that the older Socrates, who usually takes the position of the author in Plato's dialogues, only listens in the Sophistes and Politikos and does not raise any objections, i.e. apparently approves the results. However, not all historians of philosophy share this understanding. According to different hypotheses, Plato keeps a critical distance from the method of investigating the foreign and wants to show the reader its inadequacy. In this sense the silence of the older Socrates has even been interpreted as tacit disapproval. Giuseppe Agostino Roggerone believes that the stranger's point of view is not that of Plato, but that of the young Aristotle , who at the time the dialogue was written was still one of Plato's pupils. The opposite view, which predominates in research, according to which the stranger functions as Plato's spokesman, is represented by Maurizio Migliori and Thomas Alexander Szlezák , for example . Szlezák sees the stranger as a didactically versed, intellectually superior dialectician .

In the Sophistes , Theodoros introduces the stranger as a “companion” of the philosophers around Parmenides and his pupil Zeno of Elea . Parmenides and Zenon lived in the then Greek-settled southern Italy , where Parmenides was the most famous representative of the Eleatic school named after his hometown Elea . Thus, according to Plato's account, the foreign also belongs to this direction. However, the stranger does not appear as a consistent representative of the pure teaching of the Eleatic school. Rather, he knows and criticizes the weaknesses of the rigid Eleatic worldview. In this his view agrees with that of Plato, whose ontology (doctrine of being) presupposes overcoming the Eleatic concept of being and non-being.

There is no reliable evidence for the existence of the younger Socrates. Therefore, it is sometimes doubted in research that he is a historical person. Tuija Jatakari thinks it is fictional and says that Plato himself is hiding behind this name. While it cannot be ruled out that it is a figure invented by Plato, the prevailing research opinion is that it is likely that he actually lived. If so, he was a peer of Plato and Theaetetus. In the Sophistes Theaetetus calls him his "fellow practitioner" with whom he is used to endure hardships. The strenuous exercise together - Plato uses a term from gymnastics - probably means scientific activities. Apparently the younger Socrates belonged to the distinguished members of the Platonic Academy , the place of philosophical research and teaching founded by Plato.

In his metaphysics, Aristotle criticized what he believed to be a misleading comparison of a Socrates. Even ancient Aristotle commentators identified this thinker with Plato's younger Socrates. Although this equation is hypothetical, it is considered plausible in research. Aristotle complained that Socrates' approach meant that living beings were treated like mathematical objects. They would be defined independently of their material components, just as one defines a circle without reference to the matter in which it is represented. Socrates had evidently held the view that the organically divided body was as insignificant for humans as the material from which an image is formed for a geometrical figure and therefore does not belong to the definition of humans.

The younger Socrates played a constructive role in the Politikos , but made relatively little contribution to gaining knowledge. Sometimes he reacts rashly and lacks caution. He overlooks the problem of assertions that he makes or that he hastily approves. Often he is not or only partially able to follow the explanations of the stranger. Obviously he has not yet received a thorough philosophical training.

The mathematicians Theodoros and Theaetetos, who are marginal figures in the Politikos , are certainly historical figures. Theodoros taught both in his North African hometown of Cyrene and in Athens; Theaetetus was his pupil. Plato appreciated both. He has drawn a very favorable picture of Theaetetus, whom he considered a brilliant scientist.

content

The introductory talk

After the role of the sophist had been clarified in the previous dialogue, the Sophist , Socrates, Theodoros, the stranger from Elea, Socrates the Younger and Theaetetus now turn to a new topic. You have already agreed that sophistry is to be viewed as a fraud. The sophists, however, claim to have valuable knowledge, which they claim to be wisdom and the basis of political success and which they supposedly impart to their students. Hence some people confuse philosophers with sophists; others see the philosophers as statesmen, still others think they are completely insane. In order to counter the confusion, the five philosophers have set themselves the task of clarifying the terms. They want to determine what the tasks of the statesman and the philosopher are in order to clearly delimit these two fields of activity from the sophistry. Genuine striving for truth and for the common good should be grasped in its peculiarity and distinguished from dubious endeavors. The stranger willingly takes the lead. At his suggestion, statecraft should be examined first. Theaetetos, who was very active in the two previous discussions, is given a break this time. In his place, the younger Socrates, who has been silent so far, is supposed to contest the discussion with the stranger, while the others listen.

The statecraft as a special form of care knowledge

In the following, the stranger determines the direction of the conversation. He gives his opinion and demonstrates the method of investigation. The younger Socrates usually only agrees or asks questions of understanding; Occasionally, however, he also expresses doubts or incomprehension if a finding of the stranger seems strange or problematic to him.

The discussants agree that, as in the Sophistes, the method of Dihairesis should be used to define the term . First of all, the stranger names the generic term, the comprehensive genre, in order to proceed from there to more and more specific sub-genres and thus finally to obtain the exact definition of what is sought. The generic term in this case is epistḗmē (knowledge, cognition), because the statesman, like everyone who practices an art, science or craft, must have a certain relevant specialist knowledge. The question now is what kind of special competence is.

First, all knowledge is divided into two classes: “cognitive”, i.e. theoretical knowledge (for example in arithmetic ) and “active” knowledge, i.e. directly practical knowledge (for example the skills of a craftsman in handling his material). Obviously, statecraft belongs to the genre of the “cognitive sciences”. These in turn are divided into "judging" and "ordering". Mathematics is judgmental because the mathematician's task is limited to showing a state of affairs. An example of arranging science is the art of building, because the builder not only has to theoretically recognize what is correct and sensible, but also implement his planning with instructions to the workers and monitor the execution. According to this division, statecraft is ordering. The regulating fields of activity, in turn, are divided into two parts: the tasks of subordinates or transmitters who pass on instructions from others, and the function of the “self-regulators” who give orders at their discretion. The latter is the case with the statesman. In this way the stranger continues with the division. In doing so, he comes to look after certain groups of living beings, pastoral work, as a sub-genus to which statecraft belongs. The shepherds, in turn, are subdivided according to the type of living being they care for.

Now Socrates wants to move forward quickly by dividing the agile living beings or "sensory beings" into two classes, animals and humans, so that the statesman can be defined as the shepherd of the human herd. Here, however, the stranger draws his attention to a methodological error. The totality of mobile living beings does not break down into the two main parts "animals" and "people", just as humanity does not break up into the two main parts "Greeks" and "non-Greeks" (" barbarians "). One must not single out a part of X from a set and define the rest as “not-X” if the elements of non-X are heterogeneous and have nothing in common apart from the fact that they do not belong to X. Since the non-Greek peoples are very different from one another, “non-Greeks” is not a definition of a specific type of human being. Likewise, “animal” in the sense of “non-human” is not a designation of a specific species of living being. Otherwise, for example, a crane could separate the cranes and combine all other living beings into the genus of non-cranes. So one must first properly subdivide living beings before one arrives at a correct definition of man. No steps may be skipped in the Dihairesis. Socrates sees that. The stranger then makes a zoological classification. He defines humans as part of the species of tame, herding creatures and finally defines them precisely within this species as a bare (featherless) biped. Accordingly, the statesman is the shepherd who has to look after the herd of these bipeds.

The inadequacy of the definition of statecraft as pastoral activity

However, the stranger is dissatisfied with the result achieved. The definition of the statesman as the shepherd of the human herd is unsatisfactory because his activity is fundamentally different from that of all other shepherds. The other shepherds, for example cattle herders, are generalists; they not only ensure order, but also breed their animals according to plan, take care of adequate nutrition and, if necessary, act as obstetricians and doctors. In the case of the human herd, however, these functions are separate: not only politicians, but also merchants, farmers, bakers, sports teachers and doctors take on responsibilities in looking after the herd. All of these specialists can therefore lay claim to the designation shepherd. But the peculiarity of the statesman must be worked out. The imprecise definition cannot do that. Socrates admits the objection is justified.

The cosmological myth

The stranger now chooses a new approach to show Socrates what is specific about statesmanship. To this end, he tells a cosmological myth that speaks of completely different living conditions in a distant mythical past. With this he wants to show that one cannot just imagine a control of the herd of people as it is familiar to the presently living from their own experience. The current tasks of a statesman represent only a special case of managing the herd within the framework of human development that extends over huge periods of time. First of all, the stranger draws attention to the fact that the myth of "joke" (paidiá) is interfered with. With this he indicates that it is more a thought experiment than a description with historical truth claims.

The myth illustrates a cyclical picture of natural history and human history. The then prevailing model of the cosmos is assumed, according to which the earth is the center of rest around which the universe rotates. Only the divine always behaves in the same way, everything else naturally tends to change constantly. Since the cosmos is under divine control, the movement of heaven is regular. The sky, however, is a material object and as such must inevitably be subject to changes, since the physicality does not allow absolute constancy. The universe cannot always rotate in the same way over an endless period of time. Therefore the direction of rotation has to reverse from time to time, so that the sun moves from west to east. However, this cannot be brought about directly by divine guidance, because this always remains the same and therefore cannot actively cause opposing things. Rather, the reversal happens because the divine guidance at regular time intervals - each time after many tens of thousands of revolutions - lets go of the universe, whereupon it begins to turn in the opposite direction. This begins a new cosmic period, after which the deity takes control again and reverses the direction of rotation. Every change in the direction of rotation represents a catastrophe for earthly living beings; few people survive this upheaval.

In the period in which the direction of rotation follows the divine guidance, the god Kronos exercises world domination; in the period of opposite movement in which the cosmos is presently, the world is subordinate to Zeus , the father of the gods , a son of Kronos. The two periods are characterized by completely opposite conditions of existence. Under Zeus humans reproduce, under Kronos they arise from the earth. While in the time of Zeus they age during a lifetime, in the time of Kronos they get younger and younger and eventually smaller as children until they disappear with death. When Kronos rules, he himself is the shepherd of the herd of men. Like a herd of animals, he fulfills all their needs with his divine power. Politicians are therefore not needed. Under Zeus, divine guidance takes a back seat, humanity has to take care of its continued existence and well-being and needs human guidance. Therefore, the term “shepherd” applies to the people carer only in the Kronos period. Kronos is really a shepherd, because as a god he differs fundamentally from his human flock and provides them with everything. Current politicians, on the other hand, are not shepherds in the full sense of the word, for they do not provide for everything and, like those they care for, are only mortals. In addition, the divine influence is much less noticeable during the reign of Zeus than under Kronos. Since the world under Zeus is largely left to itself and its tendency to chaos, phenomena of disintegration and decline occur.

A new approach

The myth has made it clear that the definition needs clarification. The statecraft must be defined more precisely: It is human control of the human herd as opposed to divine control. A fundamental distinction is also between consensus-based voluntary leadership and tyranny. Only the rule over people who voluntarily submit, the foreigner counts as statecraft. He separates the tyranny , the violent rule of an oppressor, from it, since it is of a completely different nature. According to this, statecraft is to be defined as the voluntary care of a voluntarily obedient herd of people. However, there is still no distinction between them and other care functions.

Since the stranger is still dissatisfied with the level of knowledge he has reached, Socrates asks him to understand the inadequacy of the previous considerations. The stranger replies that it is difficult to make something like this understandable if one does not take a “pattern” ( parádeigma , often imprecisely translated as “example”) to hand. In view of the difficulty of the task, he believes it is important to proceed carefully and methodically. To explain this, he makes a comparison with learning to read in school. A learner progresses from the already known to the unknown by making use of analogies. He transfers correct ideas that he has formed on the basis of the known to the unknown. In this way he grasps commonalities between what has already been understood and what has not yet been understood and works out the knowledge of the new. A suitable pattern from the area of the familiar can make the analogous nature of the unknown sought understandable.

The Weber parable

The pattern that the stranger chooses is the art of weaving , more precisely: the wool weaving. Based on their definition, it should be demonstrated and practiced how to proceed if one wants to find out what a science or art consists of. This prepares the solution to the initial problem, the determination of what constitutes the statesman and statesmanship. This part of the dialogue is known as the " Weber Parable ". In addition, the study of the pattern serves as an exercise in dialectics , the philosophical method of gaining knowledge.

The generic term, which in this case forms the starting point for the Dihairesis, is “product” (“everything we manufacture and acquire”). Man's products fall into two main groups: the things that enable him to do something and those that protect him from suffering. The means of protection are divided into antidotes (remedies) and repellants, the means of defense in armor and enclosures, the enclosures in those who are supposed to shield from prying eyes, and those who are supposed to protect against cold and heat. The means of protection against cold and heat are either shelter or coverings, the coverings either underlay (on which one sleeps) or wrappings. From the wrappings one proceeds further dividing up to the garments. Ultimately, this leads to the art of weaving, which is the most important part of clothing production.

Through this process, weaving is indeed differentiated from many related arts - such as the manufacture of felt or leather - but the stranger points out that the term “weaving art” is not adequately defined. The specialty of this art lies not only in the material, but also in the way it is used. Weaving is a process of weaving together, which is preceded by another process, which is of the opposite nature: carding (carding), which is a separation of what is connected and what is felted together. Carding is part of wool processing for the purpose of making clothes, but not part of weaving. Other operations that have nothing to do with weaving are fulling and spinning . Thus not everything that belongs to the production of woolen clothing can be counted as the art of weaving. Added to this is the production of the tools that the weaver needs; it is not weaving and yet it is part of the work that must be done to make woolen clothing.

On the basis of these considerations, the stranger realizes that an art must not only be distinguished from other arts that produce different products, but also from their own auxiliary arts, which serve to produce their product but are not involved in its production process. This leads to the distinction between the manufacturing arts, through which a certain product is manufactured and which are therefore its main causes, and auxiliary arts, which serve the manufacture of the required tools and are thus co-causes.

With the main causes of the creation of woolen clothing, the stranger first separates fulling as an art of its own. Everything else he calls the art of wool processing. This is divided into a separating and a connecting part. The parting part includes carding, but also part of the treatment on the loom. The connecting part consists of a turning and an interlacing activity. The production of the weft threads (“weft”) and warp threads (“slip”, “warp”) is twisted, the production of the fabric is interwoven . In this way, the stranger finally arrives at a precise definition of weaving: it is the art that “creates a mesh through the straight interweaving of weft and warp”.

The importance of the art of measuring

In retrospect, the question arises whether the lengthy-looking detail in this definition was appropriate or whether the same result could have been reached in a shorter way. This question leads to a new general topic: the determination of what is appropriate in each case, that is, the philosophical art of measurement. When measuring, bigger is compared with smaller. However, it is not only about determining relative proportions, but also - as with the detailed definition of a term - about something else: about the opposition between excess and lack, about what is too much or too little. In addition to the respective pair of opposites (such as larger / smaller or more / less), another factor comes into play: the right amount. This is an absolute, objective quantity on which all evaluations depend. From the perspective of the alien, knowing the right amount is the core of any science, technology or art. The appropriate lies between the extremes. Thus, the art of measuring falls into two parts. One part includes all techniques that determine quantities by comparing them with other quantities, such as measuring and comparing lengths or speeds. The other part measures what is against what should be, against the norm of what is appropriate, because what is appropriate is that which brings about all that is good and beautiful. When it comes to timing decisions, what is appropriate is the right time ( kairós ) .

If, for example, the question is asked during an investigation whether the level of detail is appropriate, it is not primarily about finding what you are looking for as easily and quickly as possible. This is a secondary issue. Far more important is whether a teacher applies the method in such a way that it generally makes the student more capable of achieving a goal. The criterion of appropriateness in teaching is not the amount of time and effort invested, but only the didactic yield.

The procedure for delimiting statecraft

Now the stranger turns back to the determination of statesmanship. In terms of method, the same task arises as in the definition of weaving. Weaving has been set apart from all other arts with which it has something in common. Likewise, statecraft is to be determined by distinguishing it from all other arts which also serve the common good and could therefore dispute its claim to care for the state.

This presents the task of delimiting statecraft as the main cause from the contributory causes as well as from other main causal arts in the state and thus to work out their peculiarity. All arts or techniques that contribute to the continued existence of the state are to be considered. While in the art of weaving only the manufacture of their tools is one of the contributory causes, in the case of the state all manufacturing industries belong to this class. In the state as a community based on the division of labor, any production of property - even those that are only for pleasure - is one of the causes of its continued existence. A change in the procedure is necessary here: Because of the diversity and variety of the activities in question and their purposes, the division of a term into two sub-terms, as has been successfully used for weaving, runs into difficulties. Therefore, the procedure must be adapted to the specificity of this case. There can be more than two items at a subdivision level.

The activities of service providers are one of the main causes of the stranger. Those involved in services include slaves, day laborers and wage workers, as well as merchants and ship owners, shopkeepers and money changers, heralds and secretaries, fortune tellers and priests. With them, the demarcation from the statesman is easy. Certain high officials determined by lot - in Athens the Archon basileus - who are also high priests and their servants form a special case ; they are so highly regarded that their authority comes close to that of the rulers.

It is more difficult to distinguish between a special group of service providers who deal with state affairs and therefore come into consideration as competitors of the statesman. The stranger describes them as men who partly “ resemble lions and centaurs and other beings of this kind”, partly “ satyrs and the weak but agile animals”; they quickly exchange appearance and ability with one another. The stranger and the younger Socrates now want to take a close look at this “strange” type of service provider and distinguish it from the statesman. The stranger calls the type of person concerned with affairs of state "the greatest magician among all sophists and the most experienced in this art". The characterization as "magician" ( góēs ) - this derogatory term is often used for charlatans, swindlers and fraudsters - shows that the stranger is extremely critical of the group of people we are talking about. From his point of view, these are dubious politicians who unjustly pretend to be statesmen and who are in reality the most sophisticated charlatans. They are the ones to whom the various existing constitutions offer the opportunity to come to power.

The stranger distinguishes the real statesman from such alleged statesmen, who is extremely rare. This owes its power neither to its wealth nor to the number of its followers. His rule is not based on arbitrariness, but it is also not legitimized by the fact that the provisions of an existing constitution are observed or that the ruled agree. Rather, what qualifies and entitles him to govern the state is exclusively his competence: his knowledge of the science of rule over people. The stranger compares this competence with that of a doctor. A doctor is not qualified as such because he has a fortune or because ignorant patients consider him competent and therefore seek treatment from him or because he follows certain written regulations. Rather, his qualification is nothing more than his expertise that enables him to actually heal. Since only professional competence counts, the various types of constitution are to be assessed exclusively from this point of view. The more similar a form of government is to the situation under such a qualified statesman, the better it is.

Statesman's discretion and legal norms

Based on this concept, the stranger draws a radical, according to the ideas of the time, offensive consequence: He claims that the real statesman is even above the law. Laws are too rigid, no legal provision can do justice to every situation and everyone affected by it. The statesman, on the other hand, is always able to make optimal decisions based on the situation. Therefore he could rule without laws or disregard existing norms. Expertise is superior to any set of rules. Since the young Socrates expresses concerns here, the stranger explains his view in detail. However, he also points out that this only applies to a wise, superior statesman in the sense of his ideal, not to other rulers. Wherever such a statesman is not available, the highest authority must be given to established laws.

The evaluation of the forms of government

The criteria for evaluating the various forms of government are derived from the findings presented. The stranger distinguishes - apart from the special case of the rule of the ideal statesman - three normal types of government: Power lies either with one person or with a few or with the crowd. In each of the three cases it is possible to rule either according to law or arbitrarily. So there are six possibilities. Among them, sole rule is best when exercised by a king who imitates the ideal statesman and adheres to the norms of law. But if the ruler is a tyrant, she is the worst of them all. The second best form of government is the aristocracy, the rule of a small elite that respects the law. But if a ruling group acts illegally, it is oligarchy, the second worst of the six possibilities. Democracy lies in the middle: if the laws are respected, it is the third best of the six forms of government, if the laws are disregarded, the third worst. Autonomy means the greatest concentration of power and therefore has the greatest positive and negative effects. Democracy is weakest because of the fragmentation of power, so it does the least. It can bring about neither very good nor very bad conditions.

The demarcation of statecraft from related activities

Three activities - those of the judge, the general and the speaker - have a certain affinity with the actions of the statesman, since they are also connected with significant power. Statecraft differs from them in that it does not have such limited tasks. Your area of responsibility includes everything that government supervision extends to. The statesman has an integration knowledge that is superior to mere specialist knowledge. Its task is not a special task, but the coordination, the comprehensive planning and the control of the whole. He doesn't do anything himself, he just gives instructions. The judges, generals and speakers are subordinate to him, their functions are serving and executing.

The statecraft as royal weaving art

After the delimitation, the positive content of statecraft remains to be determined. In the last phase of the dialogue it is worked out that there is not only a formal analogy between weaving and statecraft with regard to the procedure for defining, but also a substantive analogy: statecraft is, as it were, a “royal weave” that provides a “fabric”.

To Socrates' astonishment, the stranger does not describe the relationship between the virtues as purely harmonious. He does not share the common belief that they are all "friends" with one another. In his view, there are virtues that are at odds with one another in some way: bravery, which is characterized by speed, vehemence and sharpness, and prudence (sōphrosýnē) , which has characteristics such as slowness and gentleness. Each of these virtues has an area in which it is needed. But where that which belongs to bravery is inappropriate, it appears as arrogance and recklessness, and where that which characterizes prudence is out of place, one speaks of cowardice and indolence. People who are shaped by one of the two opposing virtues usually show little understanding for those who are inclined to the opposite.

In private life, such biases and conflicts are relatively harmless. But when they make themselves felt in politics, the effects are devastating. Exaggerated peacefulness makes defensive strength dwindle; There is no longer any effective resistance to attackers, which leads to the loss of freedom. You are then enslaved by enemies. But excessive bravery also has terrible consequences. Those so inclined seek disputes, they are belligerent and involve the state in conflicts with overpowering opponents. If they are then defeated in the recklessly ripped off wars, the state will perish. In this case, too, there is bondage at the end. Bravery and prudence are valuable qualities, but if there is a lack of balance, either of them will lead to the downfall of the state.

Here again the central importance of the correct measure, appropriateness and balanced mixture comes to light. Not only for the rulers, but for the entire citizenry, it is absolutely necessary to generate the attitude that results from the right mixture of character traits. This happens through appropriate education and guidance not only of adolescents, but of all citizens. The statesman is responsible for ordering the necessary measures. It falls to his task to recognize the characters of the people through examination, to treat each according to his disposition and to supervise all. In this the statesman is like the weaver who guides and supervises the walkers, carders and spinners. In weaving, the firmness of the brave corresponds to the texture of the tight warp, the gentleness of the prudent to that of the soft weft. The right interweaving, which the statesman has to take care of, means both the constructive interaction of the different natures in the state and the correct shaping and harmonization of the qualities in the souls of the individual citizens. In addition to joining, there is also separating, as in wool processing: the separation of the good from the bad, which is a matter of course in every “composite science”. No producer knowingly mixes the good (suitable) with the bad (unsuitable), but everyone rejects the bad. So even the statesman in the state must not tolerate the influence of bad people.

According to the teaching of the stranger, the soul has two parts: an eternal, assigned to the divine, and an animal. The royal art of weaving fulfills its task in that it unites the eternal part with a divine bond and the animal part with a human one. The divine bond harmonizes the various parts of total virtue by moving the souls of the well-educated to grasp the truth and persistently orientate themselves to the ideal of the beautiful, the just and the good. The human bond is marriage. The choice of partner is often made in the wrong way, be it from the point of view of increasing wealth and power, or be it by only connecting people of the same kind and thus reinforcing their one-sidedness. The wise statesman knows how to prevent these mistakes. He makes use of his influence to ensure that the daring and the cautious citizens do not stay among themselves, but rather interact with one another and mix through marriage. With his art of weaving together, he ensures that the two character types complement each other in a sensible way when filling offices with a clever personnel policy. By conveying the correct idea of the beautiful and the good to all citizens, he creates harmony and friendship between the opposites. Through the right interweaving of the different kinds of mind, he weaves the network of the state community, which embraces and holds the entire population together. In this way, his art produces "the most wonderful and best of all fabrics".

Political and philosophical content

State-theoretical thinking and its ethical basis

For the history of political philosophy , the division and evaluation of the forms of government as well as the discussions about the tension between stability and innovation, statesmanlike discretion and legalism are particularly significant.

As in Plato's other political and ethical works, the philosopher's considerations in Politics are based on the conviction that ethical values and norms are objective, scientifically researchable facts. From this basic assumption Plato concludes that there is a science of ethical norms corresponding to the specialist sciences. Knowledge of these norms makes the ideal statesman and their political implementation guarantees an ideal state. However, the Eleatic stranger emphasizes the extreme rarity of true statesmen. This expresses Plato's pronounced elitist thinking. He dramatically describes the contrast between the real knowledge of the statesman and the questionable opinions of normal politicians and the crowd. The statesman, whose characteristics the stranger works out in dialogue, appears as a distant ideal; his competence is contrasted with the ignorance that characterizes the usual politics.

A core concern of Plato here, as in the dialogues Politeia and Nomoi, is the uniformity of the citizens' attitudes. It is the aim of the statesman's efforts to bring it about. A comprehensive inner harmony is to be established, which shapes the character of the individuals as well as that of the entire state community. When this is achieved, statesmanlike “weaving art” turns the state into a work of art, as it were.

The methodology

The long subdivision of terms is presented in the dialogue as a requirement for a methodologically clean investigation. It is controversial in research whether this corresponds to Plato's own view and whether it is a didactic reason that prompts the stranger to attach so much importance to this cumbersome type of subdivision. According to a separate opinion, it is a parodic representation of a wrong method from Plato's point of view.

The question of the role of metaphysics

The metaphysical dimension of what is foreign is discussed controversially in research . It is about the role of the doctrine of ideas , which is a central element of Platonic philosophy, and the question of whether the dialogue contains references to the controversial " unwritten doctrine " or the doctrine of principles. In the middle of his creative period, i.e. before the emergence of the Politikos , Plato presented his theory of ideas in the Dialogue Politeia . According to her, “platonic ideas” exist as real, purely spiritual archetypes of what is sensually perceptible. Among the ideas, the idea of the good has the highest rank. It is obviously the absolute measure that is meant when the stranger speaks of measurement according to the statesmanlike art of measurement.

The problem of compliance with the law

The stranger's demand that the law be obeyed in the absence of a superior statesman with supra-legal authority raises a number of questions. In view of the possibility of serious errors of justice and injustice legitimized by law, ethical problems arise that are controversially discussed in the philosophical and historical literature. The problem of unconditional obedience to the law proves explosive against the background of the death sentence against Socrates, whose trial and execution took place soon after the fictional dialogue act. The judgment was formally correct and accepted by the accused. From the point of view of Socrates' friends and students, especially Plato, it represented the most serious injustice. In the Politikos , the foreigner addresses the possibility that in a strictly legalistic society free research is forbidden on the grounds that nobody should be wiser than the laws. Then it is considered a serious crime to introduce, for example, medical or technical innovations that go beyond the scope of the conventional and legally regulated. This is portrayed in a grotesque way in the Politikos and judged as the destruction of science. The allusion to the charges against Socrates, who was convicted of religious innovations, is obvious.

The principle of obedience to the law, which Plato also discusses in the Crito dialogue , thus proves to be problematic. In the Politikos it is generally affirmed, but only on the condition that the laws are good imitations of an ideal body of law. The stranger emphasizes the weight of tradition. He cites empirical knowledge as the criterion for quality : He grants authority to laws when they have already proven themselves, when they are the result of rich and long experience. At the same time, however, he also works out the dilemma associated with rigid regulations: Legalism is supposed to prevent arbitrary rule, but its formalistic character inhibits innovation. Stubborn adherence to existing facilities can have grotesque consequences. It can lead to the fact that prevailing wrong opinions make it impossible to obtain real knowledge. This dilemma remains unsolved. The stranger takes a conservative stance in view of the problem. He calls for consistent adherence to the conventional and tried and tested, since he does not trust individuals or groups to have the ability to improve tried and tested legislation. In the event of changes, he fears serious deterioration, because he believes that hardly anyone has statesmanship competence. He considers arbitrariness and lawlessness to be a far worse evil than all the disadvantages of legalism.

The question of teaching development

One of the most controversial topics in Plato research is the development of the philosopher's teaching. It is disputed whether he has fundamentally changed his attitude to the main questions of metaphysics and the philosophy of the state. The view of the “Unitarians”, who believe that he has consistently represented a coherent point of view, runs counter to the “development hypothesis” of the “revisionists”, who assume a serious change of heart. With regard to the philosophy of the state, it is about the differences between the state model of the Politeia and that of the later work Nomoi . Here the question is asked whether the Nomoi rather mark a renunciation of the concept of the Politeia or represent its further development. The politos stands between these two dialogues in the order in which they came into being. From a revisionist point of view, it marks a transition stage between them. This is characterized by growing skepticism about the feasibility of ideal ideas and by turning to more realistic demands. In view of the extreme rarity of “true statesmen”, Plato attaches great importance in the Politikos to the “second best solution”, adherence to tried and tested laws. In the Nomoi , he then draws further conclusions from his change of opinion. This development is linked to a less unfavorable assessment of the democratic constitution of Plato's hometown Athens. From a Unitarian point of view, this is countered by the fact that the sharp criticism of the contemporary constitutions and politicians in the Politikos is similar to the judgments in the Politeia , which speaks for continuity. The statesman of the politic , as a specialist in norms, corresponds to the “ philosopher ruler ” of the Politeia .

Also with regard to the connection between the individual virtues, opinions differ as to whether or to what extent Plato changed his position. According to a revisionist interpretation, the idea of a contradiction between two virtues presented in the Politikos represents a break with the doctrine of virtue of the Politeia , according to which the four basic virtues wisdom, bravery, prudence and justice form a unity.

The myth and its interpretations

The image of history that the stranger presents with the myth is cyclical and culturally pessimistic with regard to the current phase of the cosmic cycle . According to the description in the myth, the course of human history is an inexorable process of decay that has a cosmic cause. In this, the interpretation of history by the stranger agrees with that of the pre-Socratic Empedocles . Empedocles also assumed a world cycle, the present phase of which is characterized by the waning of unity and increasing quarrels, and which is inevitably heading towards a catastrophic end. In the myth of politics , Plato took up an abundance of material from traditional mythology and natural philosophy and redesigned it for his purpose.

Not all researchers take the myth in the literal sense as a sequence of two epochs. According to alternative interpretations, it is only about the comparison of two world states or two aspects of the current state of the world. It is also disputed whether the cosmic cycle - as is usually assumed - includes only two phases (the reign of Kronos and that of Zeus) or another, the chaotic time of transition between the two epochs of divine rule. Different versions of the three-phase model have been presented by Luc Brisson, Christopher Rowe and Gabriela Roxana Carone. According to your interpretation, the world is left to itself only in the second phase, the transition period. Hence, this time is characterized by increasing cosmic disorder. Accordingly, the present reign of Zeus is the third phase. It differs considerably from the first phase, the age of Kronos, since the divine care for the cosmos is nowhere near as comprehensive as it was then. However, it is not a decay time, but just like the first phase and in contrast to the transition period, it is characterized by a predominance of divine order. Only in the transition period does the universe turn from west to east.

A key aspect of the myth is the lack of important features of human existence in the age of Kronos. Under God's benevolent guidance, people are well looked after. Their needs are satisfied without their intervention, they live carefree like peaceful animals without technology, economy, civilization and culture. Their role is purely passive because they do not need to take any initiative. Therefore there is no state, no politics and probably also no philosophy. Although the stranger theoretically leaves open the possibility that people philosophize under the rule of Kronos, he suggests that this cannot be the case in practice.

Emergence

There is unanimous agreement in research that the Politikos is one of Plato's late works, but did not only emerge in the final phase of the philosopher's literary activity, but rather soon after the end of the middle creative period. This result is primarily due to stylistic considerations; nothing stands in the way of content. The politos should belong in the vicinity of the Theaetetos , which stylistically belongs to the middle group and in terms of content is more likely to belong to the late work.

Since there are no clear indications for determining the time of writing, the dating approaches are speculative. They fluctuate between the time around the mid-360s and the time around 353/352.

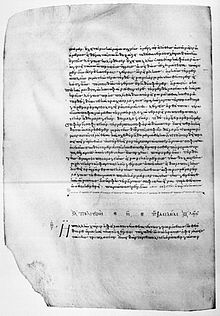

Text transmission

The ancient text tradition consists of some papyrus fragments from the Roman Empire . Furthermore, the remainder of a second century papyrus scroll contains two small pieces of text from a commentary on the dialogue. The oldest preserved medieval Politikos -Handschrift was built in 895 in the Byzantine Empire for Aretha of Caesarea made.

reception

Antiquity

The after-effects of the politos in antiquity were on the whole small; Interest in dialogue only increased in late antiquity .

Plato's pupil Aristotle dealt critically in his politics with assertions in the politicos without ever quoting this dialogue by name. In this context, Plato appears in Aristotle as "one of the earlier". In particular, Aristotle disapproved of the Eleatic stranger's assertion that there was no difference between a small state and a large household with regard to the exercise of power, rather that there was only one form of knowledge for both areas; the activities of the king, the statesman, the slave master and the steward are in principle the same from this point of view. Aristotle made a fundamental distinction between different forms of authority depending on the type of subordination and depending on the purpose of the cooperation between the commanding and the obeying. In addition, Aristotle turned against Plato's thesis that the true statesman, thanks to his competence, stands above the law, just as a doctor, thanks to his specialist knowledge, makes decisions at his own discretion and not according to existing regulations. On the other hand, Aristotle argued that the doctor could be trusted to cure the patient because he was paid for that. In contrast, political decision-makers are usually tempted to abuse power. Therefore, one should not grant a statesman any supra-legal authority. In his criticism of the evaluative classification of the constitutions in the Politikos , Aristotle sometimes misrepresented the position of the Eleatic stranger.

The Cynic Diogenes von Sinope , a younger contemporary and critic of Plato, is said to have targeted the definition of man as a featherless bipedal, given in the Politikos . According to an anecdote, he plucked the feathers from a rooster, took it to the academy and shouted: "This is Plato's man". The definition was then expanded to include the addition “with broad nails”. With this addition it is recorded in the pseudoplatonic (wrongly attributed to Plato) Horoi ("definitions"). The anecdote probably comes from the milieu of the Cynics.

In the tetralogical order of the works of Plato, which apparently in the 1st century BC Was introduced, the politos belongs to the second tetralogy. The history writer of philosophy, Diogenes Laertios , counted it among the "logical" writings and gave it as an alternative title "About royal rule". In doing so, he referred to a now-lost script by the Middle Platonist Thrasyllos .

In the epoch of Middle Platonism , dialogue seems to have received relatively little attention. As far as the Middle Platonists were concerned, their interest centered on the myth. In his examination of the cosmology of the Stoics , Plutarch relied, among other things, on the depiction of the cosmic periods in myth, whereby he interpreted the statements of the Eleatic stranger in an idiosyncratic manner. The Middle Platonist Numenios also took up the idea of the cosmic change presented in the myth, but interpreted it anthropologically . He understood the period of divine guidance as a time in which the human bodies are animated and live; the period of turning away from the divinity is the time of a body-free existence of the human spirit. Another Middle Platonist, Severos , used the myth of Politics to clarify the highly controversial question of whether the world exists forever or whether it was created in the sense of a beginning in time. He took on a mediating position. He tried to unite the two opposing concepts of eternity and origin by teaching that the cosmos in itself is eternal, but that the world order that now exists has arisen. He assigned the aspect of eternity to Kronos, the temporal Zeus.

Dialogue was valued by the late ancient Neo-Platonists . She was particularly interested in the cosmological explanations in myth. The influential Neo-Platonist Iamblichos († around 320/325), who founded and directed an important school in his Syrian homeland, included the politic in the canon of twelve dialogues that were to be dealt with in philosophy lessons . In the Neoplatonic school of Athens, which followed on from the tradition of the Platonic Academy , great importance was attached to reading the Politikos : the scholarch (headmaster) Syrianos wrote a comment on it that has not been preserved, and his successor Proclus († 485 ), the most well-known representative of the Athens School, dealt with the myth of Politics in his work Platonic Theology and in his commentary on Plato's Dialogue Timaeus . Proklos made a fundamental reinterpretation. He rejected the idea of a succession of two opposing cosmic periods, as an interruption of divine activity was not acceptable to him. According to his teaching, there is in reality no time when Kronos turns away from the cosmos, rather it is only a thought experiment by the Eleatic stranger. Proclus did not understand the contrast between the rule of Kronos and that of Zeus in the literal, temporal sense, but interpreted the myth allegorically . According to his understanding, the description of the mythical rule of Kronos relates to the conditions in the intelligible (purely spiritual) world and the description of the rule of Zeus to the order in the material world created by the divine world reason, the nous . Proclus weakened the contrast between Kronos and Zeus, which did not fit into his worldview, by assuming that the influences of the two gods worked together.

Middle Ages and Early Modern Times

In the Middle Ages, dialogue was unknown to Latin-speaking scholars of the West. In the Arabic-speaking world there was an Arabic translation of Galen's Summary of Politics by dieunain ibn Isḥāq , a scholar of the 9th century.

In the West, the politos was rediscovered in the age of Renaissance humanism . The humanist Marsilio Ficino created the first Latin translation . He published it in Florence in 1484 in the complete edition of his Plato translations. The first edition of the Greek text was published in Venice by Aldo Manuzio in September 1513 as part of the complete edition of Plato's works published by Markos Musuros .

Modern

Among Plato's works, the politician is one of those that have received comparatively little attention in modern times. However, in the 1990s, its research intensified.

Philosophical Aspects

The philosophical content of the work has been assessed very differently in modern times. In the 19th and 20th centuries, critical voices predominated. Numerous scholars found the composition inconsistent and unsuccessful, the argumentation unconvincing, the line of thought erratic and the definitions hair-splitting and unproductive. Since the late 20th century, however, there has been a tendency towards more favorable assessments.

Olof Gigon stated "an unmistakable proximity to the thinking of Aristotle"; in the remarks on the knowing statesman and the law, which begin with an overview of the forms of government, there is no sentence that could not have come from Aristotle.

Peter Sloterdijk dealt extensively with the politicos in his controversial speech, Rules for the Human Park , published in 1999 as an essay . He described it as a “discourse on human protection and discipline” and as the Magna Charta of a European “pastoral politics” or “city pastoral art”, which the stranger tries to place under transparent, rational rules. Such thinking is a fundamental reflection on "rules for the operation of human parks". The stranger presented “the program of a humanistic society”, the management of which was entrusted to an “expert kingdom”. Plato's statesman is the “full humanist” in this society; his task is "the property planning in an elite that must be specially bred for the sake of the whole". He sort and connect the people, but with their voluntary consent. The “explosiveness of these considerations” is “impossible to misunderstand” for the modern reader. By this Sloterdijk was referring to opportunities that may arise in a future biotechnological age.

The philosopher Cornelius Castoriadis held a seminar on politics at the École des hautes études en sciences sociales in Paris in 1986 . His statements there were published in book form in 1999. Castoriadis called the dialogue a baroque construction that was intended as such. Plato wanted to show how philosophical thinking works when it is authentic, that is, when it only follows its own commandments.

Literary aspects

The view is widespread that the politician , like other late dialogues of Plato, is characterized by a receding of the "dramatic element"; the dialogue character is less pronounced than in earlier writings, so that despite the formal retention of the dialogue form, the work appears more like a philosophical treatise. However, this assessment has met with contradictions. On the other hand, the objection is raised that the absence of disagreements among the interlocutors does not mean that the presentation of the philosophical investigation in the form of a dialogue is an insignificant aspect. If one neglects the dialogue character, the didactic approach of the foreign will not be appreciated.

From a literary point of view, the length and complexity of the dihairetic definitions are often criticized; Critics describe these passages as boring and tiresome. The renowned Graecist Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff made this statement as early as 1919 ; he called the Dihairese "awkward and whimsical". Constantin Ritter came to a similar judgment in 1923 in his extensive Plato monograph. He wrote that the dialogue contained a lot of "dry, hard-to-digest material" and that it contrasted with older works of the philosopher by "dispensing with ornamentation of the representation". The practice of logical rules takes place "so intrusively that in places you don't just feel bored, but downright bored". Plato consciously accepted this effect. With the dry style, he wanted to distance himself from his earlier entertaining manner of representation, presumably because his poetic images had been misunderstood. In 1974 Olof Gigon found that Plato's language in the Politikos was “filled with a very peculiar liveliness”. It is no longer the urban conversational language of the early dialogues, but shaped by the chosen, cumbersome age style of the author, who does not shy away from bold wordings and poetic expressions and often wraps what is meant in a "playful mystery". In 2002, Christoph Horn stated that the politician looked “brittle and literarily unattractive”.

According to the judgment of other scholars, the unfavorable impression is superficial; only on closer inspection does the structure prove to be well thought-out and artistic. Paul Friedländer stated that, like the philosopher's later works, the course of the dialogue was very intricate, which initially gave a confusing impression. However, it is a characteristic of Plato's late style that “a strict structure of thought shines through the erratic composition of the parts seen from the outside”. The work "with its apparently completely free interweaving" is "full of secret architecture". Egil A. Wyller expressed himself in a similar way : From outward appearances, the Politikos belongs to the most loosely composed works of Plato, its intricacy makes it appear confusing. On closer inspection, however, a figure emerges that is so convincingly clear and unambiguous that one can only wonder why not having discovered it earlier. William KC Guthrie saw in the politicos a product of Plato's masterly ability to "weave together" different topics and thus to give the reader pleasure. The philosopher had succeeded in showing the value of Dihairesis, which was far more than a mere mechanical process. Michael Erler found that the course of the dialogue was targeted, despite the seemingly confusing structure, and that it was heading towards the final definition of the statesman. Although Plato chose some detours, there was no real break in the line of thought.

Editions and translations

Editions (partly with translation)

- Donald B. Robinson (Ed.): Politikos . In: Elizabeth A. Duke et al. (Ed.): Platonis opera , Vol. 1, Oxford University Press, Oxford 1995, ISBN 0-19-814569-1 , pp. 473-559 (authoritative critical edition)

- Gunther Eigler (Ed.): Plato: Works in eight volumes . Vol. 6, 4th edition, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2005, ISBN 3-534-19095-5 , pp. 403-579 (reprint of the critical edition by Auguste Diès, 3rd edition, Paris 1960, with the German translation by Friedrich Schleiermacher, 2nd edition, Berlin 1824)

Translations

- Otto Apelt : Plato's Dialog Politikos or From the Statesman . In: Otto Apelt (Ed.): Platon: Complete Dialogues , Vol. 6, Meiner, Hamburg 2004, ISBN 3-7873-1156-4 (with introduction and explanations; reprint of the 2nd, revised edition, Leipzig 1922)

- Friedo Ricken : Plato: Politicians. Translation and commentary (= Plato: Works , edited by Ernst Heitsch and Carl Werner Müller , Vol. II 4). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2008, ISBN 978-3-525-30407-5

- Rudolf Rufener: Plato: Spätdialoge I (= anniversary edition of all works , vol. 5). Artemis, Zurich / Munich 1974, ISBN 3-7608-3640-2 , pp. 223–319 (with introduction by Olof Gigon pp. XXXIV – XLVII)

- Friedrich Schleiermacher : The statesman . In: Erich Loewenthal (Ed.): Platon: Complete Works in Three Volumes , Vol. 2, unchanged reprint of the 8th, reviewed edition, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2004, ISBN 3-534-17918-8 , pp. 741–817

literature

Overview display

- Michael Erler : Platon ( Outline of the history of philosophy . The philosophy of antiquity , edited by Hellmut Flashar , Vol. 2/2). Schwabe, Basel 2007, ISBN 978-3-7965-2237-6 , pp. 245-252, 645-648

Comments

- Seth Benardete : The Being of the Beautiful. Plato's Theaetetus, Sophist, and Statesman. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago / London 1984, ISBN 0-226-67037-6

- Maurizio Migliori: Arte politica e metretica assiologica. Commentario storico-filosofico al “Politico” di Platone. Vita e Pensiero, Milano 1996, ISBN 88-343-0829-8

- Mitchell Miller: The Philosopher in Plato's Statesman . 2nd expanded edition, Parmenides Publishing, Las Vegas 2004, ISBN 1-930972-16-4

- Friedo Ricken: Plato: Politicians. Translation and commentary (= Plato: Works , edited by Ernst Heitsch and Carl Werner Müller, Vol. II 4). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2008, ISBN 978-3-525-30407-5

- Christopher J. Rowe (Ed.): Plato: Statesman . 2nd revised edition, Oxbow, Oxford 2005, ISBN 0-85668-613-1 (Greek text, English translation and commentary)

- David A. White: Myth, Metaphysics and Dialectic in Plato's Statesman . Ashgate, Aldershot 2007, ISBN 978-0-7546-5779-8

Investigations

- Marcel van Ackeren : Knowledge of the good. Significance and continuity of virtuous knowledge in Plato's dialogues . Grüner, Amsterdam 2003, ISBN 90-6032-368-8 , pp. 274-301

- Sylvain Delcomminette: L'Inventivité Dialectique dans le Politique de Platon . Ousia, Bruxelles 2000, ISBN 2-87060-082-8

- Melissa S. Lane: Method and Politics in Plato's Statesman . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1998, ISBN 0-521-58229-6 (very detailed review by Frederik Arends: The Long March to Plato's Statesman Continued . In: Polis 18, 2001, pp. 125–152)

- Stanley Rosen: Plato's Statesman. The Web of Politics . Yale University Press, New Haven 1995, ISBN 0-300-06264-8

- Kenneth M. Sayre: Metaphysics and Method in Plato's Statesman . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2006, ISBN 978-0-521-86608-8

- Thomas Alexander Szlezák : Plato and the written form of philosophy , part 2: The image of the dialectician in Plato's late dialogues . De Gruyter, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-11-018178-9 , pp. 156-192

Collections of articles

- Peter Nicholson, Christopher Rowe (Eds.): Plato's Statesman: Selected Papers from the Third Symposium Platonicum (= Polis Vol. 12). Society for the Study of Greek Political Thought, Heslington 1993, ISSN 0142-257X (contains some of the contributions to the Congress not published in Reading the Statesman )

- Christopher J. Rowe (Ed.): Reading the Statesman. Proceedings of the III Symposium Platonicum . Academia, Sankt Augustin 1995, ISBN 3-88345-634-9

Web links

- Politics , Greek text after the edition by John Burnet , 1900

- Politics , German translation after Friedrich Schleiermacher, edited

Remarks

- ↑ On the possibly planned Dialogue Philosophos see Michael Erler: Platon , Basel 2007, pp. 246, 252 f. as well as the in-depth study of Mary Louise Gill: Philosophos. Plato's Missing Dialogue , Oxford 2012. The assumption that Plato planned such a dialogue is rejected. a. by Bernd Effe : The rule of the knower: politicians . In: Theo Kobusch , Burkhard Mojsisch (Ed.): Platon. His dialogues in the perspective of new research , Darmstadt 1996, pp. 200–212, here: 200 f.

- ↑ Plato, Theaetetus 210d.

- ↑ See on this question Mary Louise Gill: Philosophos. Plato's Missing Dialogue , Oxford 2012, pp. 200 f .; Michael Erler: Platon , Basel 2007, p. 246; Monique Dixsaut: Métamorphoses de la dialectique dans les dialogues de Platon , Paris 2001, p. 234, note 1; Friedo Ricken: Plato: Politicians. Translation and commentary , Göttingen 2008, p. 230.

- ^ Francisco J. Gonzalez: The Eleatic Stranger. His Master's Voice? In: Gerald A. Press (Ed.): Who Speaks for Plato? , Lanham 2000, pp. 161-181; Harvey R. Scodel: Diaeresis and Myth in Plato's Statesman , Göttingen 1987, pp. 14-19, 166 f. Cf. Lisa Pace Vetter: "Women's Work" as Political Art , Lanham 2005, pp. 84–92, 120 f .; David A. White: Myth, Metaphysics and Dialectic in Plato's Statesman , Aldershot 2007, pp. 7 f., 16; Friedo Ricken: Plato: Politicians. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 2008, p. 234, note 1.

- ↑ Giuseppe Agostino Roggerone: La crisi del Platonismo nel Sofista e nel Politico , Lecce 1983, pp. 45-79.

- ↑ Maurizio Migliori: Arte politica e metretica assiologica , Milano 1996, pp. 208 f., 214-216.

- ↑ Thomas Alexander Szlezák: The image of the dialectician in Plato's late dialogues , Berlin 2004, pp. 168–175, 191 f.

- ↑ Thomas Alexander Szlezák: The image of the dialectician in Plato's late dialogues , Berlin 2004, p. 175.

- ↑ Plato, Sophist 216a.

- ↑ Michael Erler: Platon , Basel 2007, pp. 241 f., 244; Friedo Ricken: Plato: Politicians. Translation and commentary , Göttingen 2008, pp. 87 f.

- ↑ Tuija Jatakari: The younger Socrates . In: Arctos 24, 1990, pp. 29-45, here: 38-45. Cf. Dietrich Kurz (ed.): Platon: Phaidros, Parmenides, Briefe (= Gunther Eigler (ed.): Platon: Werke in eight volumes , vol. 5), Darmstadt 1983, p. 465, note 159.

- ↑ Debra Nails: The People of Plato , Indianapolis 2002, p. 269; Michael Erler: Platon , Basel 2007, p. 233. Compare Maurizio Migliori: Arte politica e metretica assiologica , Milano 1996, p. 35 f.

- ↑ Plato, Sophistes 218b; see. Theaetetus 147c-d.

- ↑ Aristotle, Metaphysics 1036b24-1037a10.

- ↑ Pseudo- Alexander von Aphrodisias , In Aristotelis metaphysica commentaria , ed. Michael Hayduck , Berlin 1891, p. 514; Asklepios von Tralleis , In Aristotelis metaphysicorum libros A – Z commentaria , ed. Michael Hayduck, Berlin 1888, p. 420.

- ↑ See on Aristotle's criticism of Socrates Ernst Kapp : Socrates the Younger . In: Ernst Kapp: Selected writings , Berlin 1968, pp. 180–187, here: 182–187.

- ↑ Thomas Alexander Szlezák: The image of the dialectician in Plato's late dialogues , Berlin 2004, pp. 161–168; Mitchell Miller: The Philosopher in Plato's Statesman , 2nd, expanded edition, Las Vegas 2004, pp. 7 f .; Michael Erler: Anagnorisis in Tragedy and Philosophy . In: Würzburger Jahrbücher für die Altertumswwissenschaft , New Series Vol. 18, 1992, pp. 147-170, here: p. 154 and note 26. Cf. Maurizio Migliori: Arte politica e metretica assiologica , Milano 1996, p. 213.

- ↑ Debra Nails: The People of Plato , Indianapolis 2002, pp. 274-278, 281 f. For the role of Theodoros, see Mitchell Miller: The Philosopher in Plato's Statesman , 2nd, expanded edition, Las Vegas 2004, pp. 3-5.

- ↑ Plato, Sophist 216c-217b.

- ↑ Plato, Politicus 257a-258b. See David A. White: Myth, Metaphysics and Dialectic in Plato's Statesman , Aldershot 2007, pp. 19-21; Stanley Rosen: Plato's Statesman , New Haven 1995, pp. 8-13.

- ↑ See on Dihairesis in the Politikos Mary Louise Gill: Philosophos. Plato's Missing Dialogue , Oxford 2012, pp. 179-185; Kenneth Dorter: Form and Good in Plato's Eleatic Dialogues , Berkeley 1994, pp. 181-224; Margot Fleischer: Hermeneutische Anthropologie , Berlin 1976, pp. 148-152, 161-163, 184-189; Deborah De Chiara-Quenzer: The Purpose of the Philosophical Method in Plato's Statesman . In: Apeiron 31, 1998, pp. 91-126; Michel Fattal : On Division in Plato's Statesman . In: Polis 12, 1993, pp. 64-76.

- ↑ Plato, Politikos 258b-d. See David A. White: Myth, Metaphysics and Dialectic in Plato's Statesman , Aldershot 2007, pp. 21 f.

- ↑ Plato, Politicus 258d-262b. For the history of the designation of rulers as shepherds in ancient Greece, see Ruby Blondell: From Fleece to Fabric: Weaving Culture in Plato's Statesman . In: Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy 28, 2005, pp. 23–75, here: 23–32.

- ↑ This refers to people and animals; they are summarized in ancient Greek under the name zṓon , which is scientifically translated as “sensory beings”.

- ↑ See Michael Wedin: Collection and division in the Phaedrus and Statesman . In: Revue de Philosophie Ancienne 5, 1987, pp. 207-233, here: 220-233.

- ↑ See for the assessment of the cranes and for the determination of the specifically human Christian Schäfer : Rule and self-control: the myth of politics . In: Markus Janka , Christian Schäfer (ed.): Platon als Mythologe , 2nd, revised edition, Darmstadt 2014, pp. 203–224, here: p. 204 and note 3, pp. 217–224.

- ↑ Plato, Politicus 261e-267c. Cf. Michel Fattal: Logos, pensée et vérité dans la philosophie grecque , Paris 2001, pp. 182–184; Mitchell Miller: The Philosopher in Plato's Statesman , 2nd, expanded edition, Las Vegas 2004, pp. 19-33; Friedo Ricken: Plato: Politicians. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 2008, pp. 100–106.

- ↑ Plato, Politicus 267c-268d. See Mitchell Miller: The Philosopher in Plato's Statesman , 2nd, expanded edition, Las Vegas 2004, pp. 35 f .; Friedo Ricken: Plato: Politicians. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 2008, pp. 106–108.

- ↑ Plato, Politicus 268d. Cf. Friedo Ricken: Plato: Politikos. Translation and commentary , Göttingen 2008, p. 109 f.

- ↑ See Richard D. Mohr: God & Forms in Plato , 2nd, revised edition, Las Vegas 2005, pp. 149–165; Hans Herter : God and the world in Plato . In: Hans Herter: Kleine Schriften , Munich 1975, pp. 316–329.

- ↑ Plato, Politicus 268d-270d. See David A. White: Myth, Metaphysics and Dialectic in Plato's Statesman , Aldershot 2007, pp. 38-43; Friedo Ricken: Plato: Politicians. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 2008, pp. 111–118.

- ↑ Plato, Politicus 270d-276d. See Elizabeth E. Pender: Images of Persons Unseen , Sankt Augustin 2000, pp. 123-139; Stanley Rosen: Plato's Statesman , New Haven 1995, pp. 48-66; David A. White: Myth, Metaphysics and Dialectic in Plato's Statesman , Aldershot 2007, pp. 43-59; Friedo Ricken: Plato: Politicians. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 2008, pp. 118–135.

- ↑ Plato, Politicus 274e-277a. See Mitchell Miller: The Philosopher in Plato's Statesman , 2nd, expanded edition, Las Vegas 2004, pp. 53-55; David A. White: Myth, Metaphysics and Dialectic in Plato's Statesman , Aldershot 2007, pp. 61-64; Friedo Ricken: Plato: Politicians. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 2008, pp. 136–139.

- ^ Plato, Politikus 277a – c. Cf. Friedo Ricken: Plato: Politikos. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 2008, pp. 139–141.

- ↑ Kenneth M. Sayre opposes the translation with “Example”: Metaphysics and Method in Plato's Statesman , Cambridge 2006, p. 97. Cf. Melissa S. Lane: Method and Politics in Plato's Statesman , Cambridge 1998, p. 46 Note 67.

- ↑ Plato, Politicus 277d-279b. Cf. Friedo Ricken: Plato: Politikos. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 2008, pp. 142–147; Mary Louise Gill: Philosophos. Plato's Missing Dialogue , Oxford 2012, pp. 188 f .; Mitchell Miller: The Philosopher in Plato's Statesman , 2nd expanded edition, Las Vegas 2004, pp. 57-59; David A. White: Myth, Metaphysics and Dialectic in Plato's Statesman , Aldershot 2007, pp. 64-68; Stanley Rosen: Plato's Statesman , New Haven 1995, pp. 81-97.

- ↑ On the technical aspect of antique textile production see Katharina Waack-Erdmann: Die Demiurgen bei Platon und their Technai , Darmstadt 2006, pp. 30–39.

- ^ Plato, Politikos 279a – c; see. 285c-286b. On the interpretation of the comparison between weaving art and statecraft and on the methodology of the foreign see Sylvain Delcomminette: L'Inventivité Dialectique dans le Politique de Platon , Bruxelles 2000, pp. 238-258, 273-320; David A. White: Myth, Metaphysics and Dialectic in Plato's Statesman , Aldershot 2007, pp. 68-74, 78f., 97f., 118-129; Stanley Rosen: Plato's Statesman , New Haven 1995, pp. 81-118; Kenneth M. Sayre: Metaphysics and Method in Plato's Statesman , Cambridge 2006, pp. 77-112, 131-135; Melissa S. Lane: Method and Politics in Plato's Statesman , Cambridge 1998, pp. 56-61.

- ↑ Plato, Statesman 279b-280a. See Stanley Rosen: Plato's Statesman , New Haven 1995, pp. 101-104; Mitchell Miller: The Philosopher in Plato's Statesman , 2nd, expanded edition, Las Vegas 2004, pp. 60 f.

- ↑ Plato, Politicus 280a-281d.

- ↑ Plato, Politicus 281d-e.

- ^ Plato, Politikos 282a – 283a. See Stanley Rosen: Plato's Statesman , New Haven 1995, pp. 112-118; Mitchell Miller: The Philosopher in Plato's Statesman , 2nd expanded edition, Las Vegas 2004, p. 62; Friedo Ricken: Plato: Politicians. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 2008, pp. 150–152.

- ↑ On the terminology, see Yvon Lafrance: Métrétique, mathématiques et dialectique en Politique 283 c - 285 c . In: Christopher J. Rowe (Ed.): Reading the Statesman , Sankt Augustin 1995, pp. 89-101, here: 90-94.

- ^ Plato, Politikos 283a – 285c. Cf. Thomas Alexander Szlezák: The image of the dialectician in Plato's late dialogues , Berlin 2004, pp. 176–180; Friedo Ricken: Plato: Politicians. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 2008, pp. 155–163; Kenneth M. Sayre: Plato's Late Ontology , 2nd supplemented edition, Las Vegas 2005, pp. 319-351; Giovanni Reale: On a new interpretation of Plato , 2nd, expanded edition, Paderborn 2000, pp. 332–338; Stanley Rosen: Plato's Statesman , New Haven 1995, pp. 119-135.

- ↑ Plato, Politicus 285c-287a. See Mitchell Miller: The Philosopher in Plato's Statesman , 2nd expanded edition, Las Vegas 2004, pp. 69-72; David A. White: Myth, Metaphysics and Dialectic in Plato's Statesman , Aldershot 2007, pp. 91-96; Stanley Rosen: Plato's Statesman , New Haven 1995, pp. 135-138.

- ^ Plato, Politikos 287b. Cf. Friedo Ricken: Plato: Politikos. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 2008, pp. 165–167.

- ↑ Plato, Politikos 287b – 289d. See Mitchell Miller: The Philosopher in Plato's Statesman , 2nd, expanded edition, Las Vegas 2004, pp. 74-85; Frédérique Ildefonse: La classification des objets. Sur un passage du Politique (287 b - 289 c). In: Michel Narcy (ed.): Platon: l'amour du savoir , Paris 2001, pp. 105–119.

- ↑ The "ship's master " (naúklēros) was both owner and captain of a ship.

- ↑ Plato, Politicus 289c-291a. See Mitchell Miller: The Philosopher in Plato's Statesman , 2nd, expanded edition, Las Vegas 2004, pp. 84-86; David A. White: Myth, Metaphysics and Dialectic in Plato's Statesman , Aldershot 2007, pp. 101-103.

- ↑ Plato, Politicus 291c.