photojournalism

Photojournalism (also: press photography or picture reporting ) uses the forms and means of photography to illustrate reports on backgrounds in politics, culture and other areas of social importance or to present events exclusively in a pictorial way.

The beginnings of photojournalism go back to the second half of the 19th century, with technical innovations such as the dry gelatine process or the invention of roll film paving the way for mobile reporting. Although early photo reporting was subject to thematic restrictions compared to the work of press cartoonists due to long exposure times , it prevailed in the long term due to its greater authenticity in the course of the development of new printing processes. This and the development of 35mm cameras such as those from Leica led to the first golden age of photojournalism in the interwar period, in which press photographers such as Erich Salomon and illustrated magazines such as the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung played a pioneering role. All this changed when the National Socialists seized power, as a result of which numerous Jewish photojournalists emigrated and photojournalism was further developed, especially in the United States. The post-war period saw a second heyday of photojournalism, dominated by mass magazines such as Life , which came to an end with the triumph of television and the associated losses in advertising revenue for magazines. Finally, at the turn of the 21st century, increasing digitization led to fundamental changes in the media landscape, which also transformed photojournalism.

Today, photojournalists work in local journalism , sports photography , war and crisis photography, tabloid journalism, as well as science and nature photography .

Since 1955, particularly outstanding photojournalistic work has been honored in the “ World Press Photo of the Year ” competition .

story

The beginnings

Forerunners of photojournalism

The actual history of photojournalism begins with the unrestricted printability of photos in newspapers and illustrated magazines in the late 19th century. Even before that, however, photos were used to document world-historical events. The first "reporting" photo is a photo taken by the German daguerreotypist Hermann Biows , who documented the destruction of the Hamburg fire of 1842 in the area of the Small Alster . Because of the difficulty of reproducing such photos in print, the early photojournalistic photographs served as models for woodcuts or copperplate engravings that illustrated the accompanying text and made the event vivid to a mass audience.

The working conditions of the early reportage photographers were extremely difficult, especially before the invention of handy cameras. Photographers like the Brit Roger Fenton traveled to war zones with their mobile photo laboratories. The collodion process that was common at the time required complex coating, exposure and development of the glass plates that were carried on site. The photographic possibilities were also limited in those early years. The low sensitivity of the collodion process forced the photographer to use long exposure times, which made it impossible to capture moving objects.

The American Civil War from 1861 to 1865 was documented extensively in photographs for the first time. The Army of the Northern States alone had around 400 accredited photographers who captured the events of the war in thousands of pictures. The photographers around Mathew Brady , who sent more than 20 of his employees to the war zone at his own expense , gained particular notoriety . Although the recordings made in this way conveyed the events of the war particularly vividly, the undertaking meant commercial ruin for Brady. In 1896 he died impoverished in New York.

Technical innovations pave the way for mobile photo reporting

With the invention of the dry gelatine process by the English doctor and amateur photographer Richard Leach Maddox in 1871 and the later improvement of the technique by Charles Bennet seven years later, mobile photography was made significantly easier. Compared to wet collodion plates, dry gelatine plates were more durable and more convenient to take with you when travelling. In addition, due to the higher light sensitivity of the plates, the new process also made it possible to take pictures with significantly shorter exposure times.

Another technical revolution was the invention of roll film , which was used in the legendary Kodak No. 1 camera from 1889 and conquered the mass market with it. A distinctive feature of the Kodak No. 1 was the film processing service provided by Eastman Kodak : the camera was preloaded with film for 100 exposures and, once full, was returned directly to Kodak. After processing in the company's laboratory, the developed negatives were returned with prints and a new film inserted in the camera. With the development of the Kodak No. 1, it no longer required much previous knowledge to capture events in the picture.

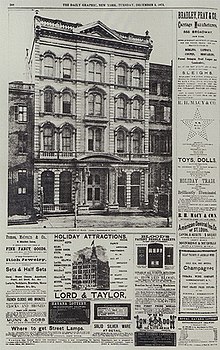

Replacement of the press artist by the press photographer

Although the American newspaper Daily Graphic published a photo using the halftone printing process as early as 1873 , it took around 30 years for newspapers and illustrated magazines to switch to the new technology across the board. It was only at the beginning of the 20th century that the engravings made manually based on photos were replaced by photographs. Because the autotype printing process developed by the German entrepreneur Georg Meisenbach in the 1880s was complex and required high-quality paper, photographic illustrations were initially only used in illustrated weekly magazines such as the American Collier's Weekly . After the turn of the century, the London newspaper Daily Mirror became the first daily newspaper in the world to appear exclusively with photographs.

The switch from drawn illustrations to photos was initially controversial. While press animators used their creative freedom to dramatize the subjects depicted in order to increase circulation, the early press photos of still scenes often came across as sober and boring. With the development of high-speed lenses and faster shutters , however, press photography took off. The shorter exposure times of up to a thousandth of a second now made it possible to capture even moving subjects in the picture. Snapshots not only gave the audience the impression of getting closer to the event shown, they were also more authentic than drawn illustrations and thus strengthened the documentary character of the illustrations.

The increasingly rapid replacement of hand-drawn images with photos meant that thousands of engravers lost their jobs - many of them becoming photographers. The growing demand from newspapers for photos also led to the establishment of the first photo agencies, which supplied newspapers with up-to-date photos for a fee. The emergence of these agencies was accompanied by further professionalization in the production and distribution of press photos.

From the interwar period to the end of World War II

The first golden age

During the First World War , the public saw little of the reality of the battlefields due to the restrictive handling of war reporting and the strict censorship laws. In his Handbook of Photojournalism , written together with Lars Bauernschmitt, Michael Ebert therefore describes this period as “photojournalistically underexposed”. In the interwar period , on the other hand, as Wolfgang Pensold puts it in his history of photojournalism , “a veritable flood of images overwhelmed our contemporaries.” Illustrated magazines such as the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung and the Münchner Illustrierte Presse reached a large audience.

One of the most famous press photographers of that time was Erich Salomon from Berlin, who caused a sensation with his photo reports and the mostly secret shots he took with the new type of Ermanox camera, which was extremely bright for the time and at the same time relatively small . In the 1930s, Salomon then used a 35mm camera from Wetzlar -based Leica , which was even more compact than the Ermanox . The small-format film material used in cameras such as the Leica I benefited from the fact that its fine grain allowed enlargements to be made from the small negative. This rendered the unwieldy large plate cameras, which had previously benefited from their better image quality, obsolete for use in press photography.

Due to the increased demand for pictures from the illustrated press, more picture agencies came into being. The agencies Weltrundschau and Dephot (of Deutscher Photodienst ) were founded in Berlin. At the same time, the modern form of photo reportage emerged at the end of the 1920s. Simon Guttmann , the head of Dephot , encouraged his photographers to create coherent series of shots for later use in photo stories. In Vienna, Lothar Rübelt is one of the pioneers of modern reportage photography. The picture stories created in this way no longer report solely on political or social events, but are also devoted to aspects of everyday life. Anton Holzer points out that with "well-done reports [...] news, entertainment, exciting stories, often also advertising and propaganda [merge] into a new type of image." Wolfgang Pensold sees this birth of modern photo reports as a reaction to the competition of the newsreels in cinemas: "Photography or the photo illustrated should remain competitive with the current topical pictures".

Striving for objectivity: the influence of documentary photography

As early as the second half of the 19th century, photographers such as Jacob August Riis and Lewis Hine had begun to raise public awareness of the lives of people on the fringes of society with their pictures. In the mid-1930s, American economist Roy Stryker , in his capacity as head of information for the American Farm Security Administration (FSA), took up this tradition and hired photographers to document the plight of poor farmers during the Great Depression . Unlike Riis and Hine, however, Stryker's recruited photographers acted on government contracts with the clear goal of convincing the public and the United States Congress of the need for relief programs. In this way, around 250,000 pictures were taken between 1935 and 1943, which reached large sections of the population via newspapers, magazines, brochures, books and exhibitions.

In accordance with Stryker's specifications, however, certain motifs such as the sometimes brutal suppression of workers' strikes or those documenting the high infant mortality rate were excluded. Between the employees of the FSA and photographers like Walker Evans - who refused politically motivated jobs - there were repeated arguments that culminated in Evans' dismissal in 1937.

Nevertheless, Evans and a few other photographers managed to develop a special style aimed at realistic depiction in this area of tension between propaganda assignment and their own claim. Dorothea Lange also pursued a documentary approach that wanted to show things as they are. In her illustrated book An American Exodus , published in 1939 , Lange emphasized the objectivity she was aiming for - instead of arranging the subject of the photograph, she accustomed the subjects to the presence of her camera, in order to be able to create unconstrained shots. With this quest for authenticity, the work of photographers such as Evans, Lange, and others have influenced an entire generation of photojournalists. Today, the FSA project is regarded as the trigger for the development of documentary photography into an independent genre and as a trend-setter for modern photojournalism.

The turning point of the Second World War

The seizure of power by the National Socialists marked a turning point in the history of German photojournalism. While Jewish photographers like Erich Salomon were murdered in concentration camps or emigrated, numerous others - such as Hitler's personal photographer Heinrich Hoffmann - put themselves in the service of the Nazi regime's propaganda. Illustrated magazines such as the Illustrierte Beobachter , co-founded by Hoffmann and published by the NSDAP , developed into mouthpieces for the National Socialist regime.

The emigration of Jewish photographers to England, France and the United States had a major impact on the development of photojournalism there. Stefan Lorant of the Münchner Illustrierte , one of the pioneers of modern photojournalism, founded the photo-illustrated Picture Post in London . The French magazine Vu , which was created partly on the model of the Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung , offered numerous emigrants a professional home. Alfred Eisenstaedt , formerly a freelancer for the Berliner Tageblatt , provided images for Life magazine, founded by Henry Luce in New York in 1936 , which went on to become the most successful photo magazine of its time.

In contrast to the First World War, the importance of images for psychological warfare was already recognized at the beginning of the Second World War . Reich Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels demanded in June 1940, "[...] that both the severity, the size and the sacrifice of the war should be shown, but that an overly realistic representation, which instead could only promote the horror of war, should definitely be allowed have not done."

While American magazines such as Life still used the pictures of German photographers at the beginning of the war, this situation changed when the USA entered the war in 1941. In addition to army photographers, civilian photographers such as Robert Capa were also allowed to do photo reporting. Although their images were also subject to censorship, some of the Allied photographers strove to show the war as it really was , unlike the photographers of the German propaganda company. Others, like the British photographer George Rodger or the American war correspondent Margaret Bourke-White , provided evidence of the Holocaust with their photos of German concentration camps .

The second golden age of photojournalism

Magnum and the humanistic zeitgeist of the post-war years

Two years after the end of the war, photographers Robert Capa , Henri Cartier-Bresson , David Seymour and George Rodger founded the independent photo agency Magnum Photos in New York . Under the impression of the atrocities of the Second World War, they placed their work under a humanistic model. They saw themselves – as Pensold puts it – “not just as objective observers, but as reporters inspired by enlightenment who direct their attention to injustice.” They also tried not to be subject to the arbitrariness of the photo editors and the constraints of the layout. They were therefore opposed to possible falsifications of the image statement intended by the photographer, for example through subsequent cropping . When using their photos, they insisted that the photographer be named and that the image rights remain with the author.

The humanistic zeitgeist of the post-war years reached its climax in the photo exhibition The Family of Man , curated by Edward Steichen . During the war, Steichen headed a US Navy photography department. Influenced by his war experiences, he now endeavored to emphasize the equality of all people in a monumental picture show in order to put an end to hatred and violence. The fact that The Family of Man was visited by well over 10 million people after it opened in 1955 “contributed […] significantly” – according to Bauernschmitt and Ebert in their Handbook of Photojournalism – “the 20th century definitively to become that of the images.”

Large magazines shaped the photojournalism of the second golden age

In the three decades following the end of World War II, major magazines played a dominant role in informing and entertaining the general public. The sheet Today - A New Illustrated Magazine , which was created in the American occupation zone in July 1945 based on the model of Life , was the first German-language illustrated magazine after the end of the war and was primarily used for educational purposes. Although the paper relied on high-quality images and employed the later Magnum photographer Ernst Haas as its photo editor, it was unable to cope with the increasing competition from the new German magazines such as Quick and Stern and was discontinued as early as 1951. At the same time, photojournalism in the early years was still strongly influenced by those who had already had a career during National Socialism. Photographers such as Benno Wundshammer , Hilmar Pabel and Hanns Hubmann developed into stars of the post-war German photojournalism scene, regardless of their earlier involvement in propaganda companies .

According to Bauernschmitt and Ebert, it was not until the early 1960s that a “young and unencumbered generation” of photojournalists emerged in Germany. The youth magazine Twen , which first appeared in 1960, was characterized by elaborate photo spreads and expressive shots by the Munich-based American photographer Will McBride . McBride not only developed a new visual language, but also promoted debates about where the limits of what was permitted in photojournalism lay. At a time when the depiction of pregnant women was considered obscene, he triggered a nationwide scandal with a photo of his pregnant wife Barbara and in this way promoted the discussion about a modern image of women.

Also part of the new generation of West German photographers was Thomas Höpker , who became known through a photo report published in Kristall magazine in 1964 and began working for Stern that same year . As one of the few German photojournalists, Höpker became a member of Magnum Photos . Between 2003 and 2007 he even represented the agency as its president.

The Crisis of the Mass Illustrated

When the advertising industry began to turn to television and the most important source of income, the magazines, slowly dried up, the heyday of the mass magazines came to an end. Readers became increasingly interested in special interest magazines , accelerating the decline of the large consumer magazines . The first magazines had already disappeared from the market in the 1950s and 1960s: Collier's and the Picture Post appeared for the last time in 1957. In 1969, the Saturday Evening Post was discontinued. The American magazine Look was discontinued in 1971 and just a year later Life also ceased publication. Although the crisis of the mass magazines was triggered by economic factors such as increased cost pressure and the loss of advertising income, this crisis is sometimes interpreted as a sign of a loss of importance for photo reportage.

In the crisis years of the 1970s, however, new magazines also established themselves, such as Geo published by Gruner + Jahr in Hamburg , which is still known today for its opulent photo spreads. However , after the end of the 1970s, none of the magazines reached a circulation of millions like in the days of Life .

From the late 1980s to today: the digital revolution and its aftermath

Although the American photojournalist and digital pioneer Ron Edmonds was already taking press photos with a digital camera in the late 1980s , the new technology only slowly gained a foothold in photojournalism in the mid-1990s. Advantages such as the possibility of fast transmission of the images and the elimination of the costs for film material were initially offset by disadvantages such as the high purchase price and the initially low image resolution. Due to technical developments, this situation changed dramatically from the turn of the millennium. With digital single- lens reflex cameras such as the Nikon D1X introduced in 2001 or the Canon EOS-1Ds Mark II available from 2004, press photographers had real alternatives to their analog cameras at their disposal for the first time. This ended the time when exposed films had to be sent to the editors by post, which was time-consuming and accepted the risk of loss. From now on, images were transmitted to the photo agencies within minutes via satellite, which in turn forwarded them to the newspapers and magazines in a very short time.

The consequences of digitization for photojournalism are manifold. In a work published in 2007, Elke Grittmann pointed out that the importance of photos has increased since the 1990s, as they are increasingly used as “eye-catchers” in the course of strengthening the visual and encourage the viewer to read. Lars Bauernschmitt goes one step further and postulates in the Handbook of Photojournalism , published in 2015 : “In the media today there is a compulsion to visualize. Only what can be represented in a picture has a chance of being published. What can't be shown in the picture didn't happen.” In the final chapter of his history of photojournalism , Wolfgang Pensold emphasizes the competition between citizen journalism and classic photojournalism that has arisen from mobile phone cameras. Above all, he sees the work of anonymous photo amateurs as a threat to the truthfulness guaranteed by the history and culture of traditional photojournalism. Based on the observation that television channels and online editions of newspapers are increasingly asking for videos, Pensold believes that the "traditional type of photojournalist" has had its day and that the future belongs to the visual journalist "who has to be a photographer and videographer at the same time".

Photojournalistic forms of representation (selection)

single frame

| Type | explanation | picture example | image description |

|---|---|---|---|

| portrait | The portrait serves to represent people. The photo can reflect the appearance of the person portrayed as neutrally as possible or try to capture the personality of the person portrayed through the specific facial expression. | Portrait of singer Jill Tracy , taken during an event in San Francisco in 2018. In this type of close-up, the head is often slightly cropped, as in the example opposite. In this case, the actual subject was also separated from the image background by choosing an open aperture. | |

| Environmental portrait | A special form of portrait is the " environmental portrait ", in which the inclusion of the typical environment of the person portrayed emphasizes their special features (e.g. a special talent or a certain profession). | Portrait of Engin Umut Akkayas , one of Turkey's leading scientists in molecular fluorescence and molecular logic gates, from 2010. The photo shows him in his laboratory with his PhD students at Bilkent University UNAM, Ankara. It embeds the sitter in their typical work environment to give context to the portrait. | |

| event photo | Event photos are snapshots of newsworthy events such as natural disasters, political events or sporting events. | Eyjafjallajökull eruption 2010 : The image shows the summit crater eruption of May 10th. Due to the disruption to air traffic in Europe caused by the event, the volcanic eruption in Iceland was in the media for weeks. | |

| feature | "Feature pictures" are single images that offer a change from the often negative headlines in the press and often create a positive atmosphere. According to Kenneth Kobré, they are “timeless” in that they retain their appeal long after publication, unlike, say, momentary images in political reporting. Among the motifs frequently used for such images, Kobré counts "children imitating adults" or "animals behaving like humans". | Good feature pictures are designed to evoke a response from the viewer that can range from amazement to laughter to closer inspection. The image example shows a bird statuette, which creates the impression that there is a connection between the figure and the bird droppings in front of it. |

image spreads

| Type | explanation | picture example | image description |

|---|---|---|---|

| picture series | The image series is a group of similar images. Often - as in the example on the right - this is done to show the course of an action or an event. A special characteristic of the picture series is the formal similarity of the photos: all photos were taken from the same point of view by the photographer and with the same camera settings; Time and place are consistent. | High-speed photography: a light bulb that is switched on is shot with an airsoft gun (position to the right of the lamp). Here is the first image of the series showing the bulb in its intact condition. | |

| The second image in the series shows the exploding lightbulb. Both images were taken a few milliseconds apart, with the camera position and setting being identical. | |||

| photo reportage | The photo reportage is a sequence of images that are connected to form a coherent story. The reportage is determined by a place, a person or an event as the basic motif, whereby the respective recording location, the camera settings and the choice of the image section are used to develop the dramaturgy of the story. The first and last images usually mark the beginning and end of the presentation and are often similar in form or content. | During the Bridge Together Golden Gate demonstration in January 2017, thousands of people formed a human chain across the Golden Gate Bridge to demonstrate against Donald Trump 's inauguration. This is the first and therefore the "lead image" in the series, which - as is usual with photo reports - gives an overview of the scene. | |

| The next picture shows a section of the action space, in this case the interaction of the demonstrators with the passing motorists. | |||

| “Zooming in” creates closeness. | |||

| The last picture of the sequence together with the first picture forms the frame of the photo reportage. |

Areas of application (selection)

local journalism

Local journalism is the area that demands the most flexibility from the photojournalist. The spectrum of her tasks ranges from photographing festivals, sporting events, traffic accidents, portraits, cultural events to events from club life. The work of local photojournalists is mainly published as single images, while photo reports tend to be the exception.

Working as a local photojournalist is often the entry point into the profession. For example, the German Pulitzer Prize winners Anja Niedringhaus and Karsten Thielker initially worked for local editors before launching their international careers.

Today only a few local newspapers have permanent photo reporters. Instead, they rely on freelancers or illustrate their articles with free photos that they find on the Internet. While the number of images printed in the daily press has increased in recent years, the royalties have fallen dramatically. As a result, local photojournalists are now able to make a much worse living from their income than was the case in the past.

sports photography

Sports photography has always been strongly influenced by the technical possibilities of the camera equipment used. So their history only began at the beginning of the 20th century with the advent of cameras that had a sufficiently short shutter speed to be able to capture fast movements in the picture. Today's sports photographers work with elaborately designed and at the same time heavy telephoto lenses that achieve the desired results alone in combination with an extremely light-sensitive camera sensor.

21st century digital photography has led to both increased competition and acceleration in the field of sports photography . The easier availability of powerful camera systems has ensured that the market for good sports pictures is more competitive today than it was in the days of analogue photography. In addition, sports photographers today often process their work on location and send it to their editors from the sidelines, whereas in the past they had to put a lot of effort into developing films.

War and crisis photography

Since its beginnings in the Mexican-American War (1846-1848), war photography has fundamentally changed our view of armed conflict. While the general public knew wars up until the mid-19th century only through the glorifying depiction of history painting, war photography offers a far more realistic impression of the suffering and death of soldiers and civilians.

Since the warring factions are mostly not interested in unfiltered reporting from the combat zone, photojournalists often work within a spectrum of restrictions ranging from censorship to “ embedded journalism ”. Since the First World War , photography has also been used specifically for propaganda purposes.

While the German media was reluctant to send photo reporters to war and crisis zones after the experiences of World War II , the genre was mainly shaped by American and British photographers in the second half of the 20th century. The works of Robert Capas , whose pictures of the Allied landings in Normandy are among the most well-known war photos today, or those of Eddie Adams , who are known above all for his picture of the execution of the Viet Cong Nguyễn Văn Lém by General Nguyễn Ngọc Loan in Saigon became known, reached a worldwide audience and in this way contributed greatly to the formation of public opinion.

Tabloid journalism: the paparazzi

Although the term "paparazzo" (plural "paparazzi") was first coined by Federico Fellini's film La dolce vita from 1960, photo reporters have photographed celebrities against their will in the past. In particular, the miniaturization of the camera and the development of high-speed telephoto lenses encouraged clandestine photography. The relationship between tabloid photographers and celebrities has always been ambivalent: on the one hand, there are numerous cases in which the alleged victim violently defended himself against the violation of his privacy, and on the other hand, celebrities are often dependent on paparazzi when It's about getting noticed by the public. The mutual benefit often leads to agreed productions from which both parties benefit. In order to suggest an alleged authenticity of the pictures, some paparazzi deliberately use technical flaws such as blurring or an image composition reminiscent of amateur photographers.

In public, paparazzi enjoy a rather dubious reputation. In the wake of the road death of Diana, Princess of Wales , voices arose blaming photographers for the death of "the world's most photographed woman" — though not without noting how much the princess has benefited from the paparazzi's past work had.

Science and nature photography

The Swedish photographer Lennart Nilsson (1922-2017) is considered the father of modern scientific photography . His photo reportage Drama of Life Before Birth , produced for the American Life Magazine , with which Nilsson documented the development of human embryos in the womb, was created using endoscopes specially developed for this purpose . Such was the appeal of the images that the August 30, 1965 issue of Life sold out within days. For his work, Nilsson received the Hasselblad Award in 1980 , which is considered the world's most important award in photography.

Even if nature and science photography is one of the fringes of photojournalism, animal and macro shots are very popular, not least since they have been widely disseminated on the internet. Photographs from the field of science and nature photography reach a large audience through magazines such as National Geographic , Nature , Geo , or Bild der Wissenschaft .

Ethical aspects of photojournalism

The limits of what is considered ethically acceptable in the practice of photojournalism have always been subject to changing times. Kenneth Kobré, author of the standard work Photojournalism. The Professionals' Approach , quotes the American photojournalist W. Eugene Smith , who wrote as late as 1948: "The majority of photographic stories require a certain amount of staging, redirection and direction in order to ensure the pictorial and editorial coherence of the photos." Smith describes one of the typical dilemmas of photojournalists, namely the question of the extent to which photographic documents used for journalistic purposes can be "composed" according to the photographer's ideas. In a 1961 poll of photojournalists, none of the study participants objected to repeating a groundbreaking ceremony for a photograph. A similar 1987 study of members of the US National Press Photographers Association (NPPA) found that around a third of respondents opposed such repetition. The example shows that photojournalists do not always agree on which practices are rated as acceptable and which are not. Another study from 1981 found in the course of a survey of press photographers that almost half of 19 hypothetical problem cases were assessed differently by the respondents.

|

The assassination of Robert Kennedy External link |

The possible control of the photojournalist over the image content is not the only aspect that raises ethical questions. Press photographers are often faced with the decision of whether they should actually press the shutter button on their camera in certain situations. One of the better-known examples in the history of photojournalism is the case of American photographer Boris Yaro , who captured the assassination attempt on Robert F. Kennedy for the California newspaper Los Angeles Times . When he wanted to photograph Kennedy lying on the ground, he was initially held back by a colleague. After a moment's thought, he decided to take the picture anyway. Turning to his colleague, he said, according to his own statement: "Damn, lady, that's history".

|

Funeral procession in the Gaza Strip External link |

The digital age of photography poses new problems for press photographers. At a time when images can be changed with just a few simple steps using editing tools such as Photoshop , the question always arises to what extent interventions are still justifiable and when the documentary quality of photos suffers so much from the changes that the Image is considered "manipulated". In 2013, the case of Swedish photojournalist Paul Hansen drew attention after his shot of two dead children and a grieving crowd in Gaza City, which won Press Photo of the Year , was suspected to be the result of image manipulation. While the report of the alleged manipulation quickly spread via digital networks such as Facebook and Twitter , the subsequent finding that Hansen's picture was in no way "fake" received little attention on the Internet. For Washington Post photographer Olivier Laurent, the incident is "symptomatic of photojournalism and its place in a society that has learned not to trust what it sees."

awards

The " World Press Photo of the Year " award , which has been awarded since 1955, is considered the "most prestigious and coveted award in photojournalism". Since 1960, the internationally oriented competition has been organized by the Dutch foundation World Press Photo , which was set up specifically for this purpose . After the award ceremony, the winning pictures will be shown in a traveling exhibition and published in a yearbook. In this way, the award-winning photos reach an audience of millions.

The American Pulitzer Prize , which has been awarded since 1917 , has been awarded to press photos in the Feature Photography category since 1968 and in the Breaking News Photography category since 2000 .

There are also other competitions for photojournalists, such as the "Pictures of the Year International Competition" of the New York news and press agency Associated Press , which celebrated its 75th edition in 2018.

professional associations

The Danish Pressefotografforbundet is the world's oldest professional association for photojournalists. The organization was founded by six press photographers in Copenhagen in 1912 and had 868 members at its 75th anniversary in 1987.

In the United States, the National Press Photographers Association (NPPA), founded in 1947, is one of the world's largest organizations for photojournalists. In addition to regular competitions, the NPPA also offers its 6,500 members (as of 2019) a range of training opportunities and a job exchange. In addition, the NPPA obliges its members to comply with ethical rules in the field of photo reporting.

In Germany, the Freelens organization, founded in 1995, also has its own professional association for photojournalists and photographers. According to its own statement, Freelens is the largest photographers' organization in Germany with 2400 members (as of 2019). German photojournalists also have their own specialist groups in the large journalists ' associations, the German Journalists' Union (dju) and the German Journalists' Association (DJV). In Austria, the Federal Guild of Professional Photographers, together with the Austria Press Agency , has been awarding the “Objective” press photo prize since 2005. In Switzerland, 200 photojournalists (as of 2019) are organized in their own section of the Association of Media Workers impressum .

training

The term photojournalist is not protected. There is no regular training. In addition to an apprenticeship, which usually does not focus on photojournalism, a photography degree is possible.

Journalism schools and journalism academies offer courses in photojournalism as part of the training and further education of journalists.

The Magdeburg University of Applied Sciences has been offering the Photo Journalism course since the 2008/2009 winter semester. Since October 2010, the Hanover University of Applied Sciences has offered a degree in "Photojournalism and Documentary Photography".

literature

- manuals

- Lars Bauernschmitt / Michael Ebert: Handbook of Photojournalism. History, forms of expression, areas of application and practice , Heidelberg 2015, ISBN 978-3-89864-834-9 (authoritative work in German).

- Kenneth Kobre: Photojournalism. The Professionals' Approach , Boston, New York [u. a.] 1985, 2 1991, 3 1995, 4 2000, 5 2004, 6 2013, 7 2017, ISBN 978-1-138-20170-5 (the standard work in English).

- General representations

- Wolfgang Pensold: A History of Photojournalism: What Matters Are the Pictures , Wiesbaden 2015, ISBN 978-3-658-08297-0 .

- Anton Holzer: Frenzied Reporters. A cultural history of photojournalism , Darmstadt 2014, ISBN 978-3-86312-073-3 (focusing on Austria and the period leading up to the end of World War II).

- Elke Grittmann / Irene Neverla / Ilona Ammanno (eds.): Global, local, digital - photojournalism today , Cologne 2008, ISBN 978-3-938258-64-4 .

- Julian J. Rossig: Photojournalism , Constance [u. a.] 2006, 2 2007, 3 2014, ISBN 978-3-86764-482-2 (guideline that primarily deals with the practical aspects of journalistic photography).

- Rolf Sachsse: Photo journalism today: profession, training, practice , Munich 2003, ISBN 978-3-471-77269-0 .

- Sabrina Hanneman: Photojournalism as a profession: crossing the line between art and journalism. Vienna 2009, ISBN 9783639119787 .

- to individual aspects

- Felix Koltermann: Photo reporter in conflict. International photojournalism in Israel/Palestine , Bielefeld 2017, ISBN 978-3-8376-3694-9 .

- Elke Grittmann: The political picture. Photojournalism and press photography in theory and empiricism , Cologne 2007, ISBN 978-3-938258-31-6 (strongly theoretical work).

- Ludwig AC Martin (ed.): Hundred years of world sensation in press photos. Harenberg, Dortmund (= The bibliophile paperbacks. Volume 120).

web links

Remarks

- ↑ Lars Bauernschmitt / Michael Ebert, Handbuch des Fotojournalismus , Heidelberg 2015, p. 1.

- ↑ Bauernschmitt / Ebert, Handbook of Photojournalism , p. 2f.

- ↑ Bauernschmitt / Ebert, Handbuch des Fotojournalismus , p. 7.

- ^ Cf. on this and on the following Wolfgang Pensold, Eine Geschichte des Fotojournalismus , Wiesbaden 2015, pp. 28-30.

- ↑ On this and on the following Bauernschmitt / Ebert, Handbuch des Fotojournalismus , p. 30.

- ↑ Bauernschmitt / Ebert, Handbuch des Fotojournalismus , p. 37.

- ↑ a b Pensold, History of Photojournalism , p. 49.

- ↑ On this and the following see Pensold, History of Photojournalism , p.

- ↑ Pensold, History of Photojournalism , p. 51.

- ↑ Anton Holzer, Raging Reporters. A cultural history of photojournalism , Darmstadt 2014, p. 204f.

- ↑ a b Holzer, Kulturgeschichte des Fotojournalismus , p. 205.

- ↑ Pensold, History of Photojournalism , p. 51.

- ↑ Bauernschmitt / Ebert, Handbuch des Fotojournalismus , p. 53.

- ↑ Pensold discusses this critically in more detail in his History of Photojournalism , p. 62.

- ↑ Dorothea Lange / Paul Schuster Taylor, An American Exodus. A Record of Human Erosion , New York 1939, pp. 5f., here adapted from Pensold, History of Photojournalism , p. 63.

- ↑ Bauernschmitt / Ebert, Handbuch des Fotojournalismus , p. 52.

- ↑ For this and the following see Pensold, History of Photojournalism , pp. 55f.

- ↑ Ministerial Conference of June 10, 1940, quoted here from Pensold, History of Photojournalism , p. 74.

- ↑ So Pensold in his History of Photojournalism , p. 79.

- ↑ Pensold, History of Photojournalism , p. 92.

- ↑ Bauernschmitt / Ebert, Handbuch des Fotojournalismus , p. 72.

- ↑ On this and the following, see Bauernschmitt / Ebert, Handbuch des Fotojournalismus , p.

- ↑ Bauernschmitt / Ebert, Handbuch des Fotojournalismus , p. 78.

- ↑ Thomas Bärnthaler, "In the sixties I was mostly pregnant" , interview with Barbara Siebeck, in: Süddeutsche Zeitung Magazin of February 25, 2010, last accessed on May 18, 2019.

- ↑ Bauernschmitt / Ebert, Handbook of Photojournalism , p. 94f.

- ↑ Holzer, Kulturgeschichte des Fotojournalismus , p. 441.

- ↑ For example, Markus Ehrenberg: "The decline of the best-known American reportage magazine [ Life ] reflects the loss of importance of photo reportage", in: President in bathing suit. Robert Lebeck Collection in the German Press Museum , in: Der Tagesspiegel of November 3, 2016, last accessed on May 18, 2018.

- ↑ So Bauernschmitt / Ebert, Handbuch des Fotojournalismus , p. 98.

- ↑ Pensold, History of Photojournalism , pp. 188f.

- ↑ Grittmann, The political picture , p. 15.

- ↑ So Lars Bauernschmitt in Bauernschmitt / Ebert, Handbuch des Fotojournalismus , p. 388.

- ↑ Pensold, History of Photojournalism , p. 192.

- ↑ Pensold, History of Photojournalism , p. 189.

- ↑ Elke Grittmann, The political picture. Photojournalism and press photography in theory and empiricism , Cologne 2007, p. 42 and 363.

- ↑ Kenneth Kobré: "Wire service photos showing President Bush giving his inaugural speech carry little interest today. Yet feature pictures […] will long retain their holding power”, in: Photojournalism. The Professionals' Approach , 7th edition, New York 2017, p. 87.

- ↑ Kobré, Photojournalism , pp. 88–90.

- ↑ For more details, Bauernschmitt / Ebert, Handbuch des Fotojournalismus , p. 119f.

- ↑ For more details, see Bauernschmitt / Ebert, Handbuch des Fotojournalismus , p. 172.

- ↑ Bauernschmitt / Ebert, Handbuch des Fotojournalismus , p. 173.

- ↑ On the partial aspect of German war photography after 1945, Bauernschmitt / Ebert, Handbuch des Fotojournalismus, p. 198f.

- ↑ For example, see Roger Cohen, Diana and the Paparazzi: A Morality Tale , New York Times, September 6, 1997.

- ↑ Michael Zhang, Famous 'Valley Of The Shadow Of Death' Photo Was Almost Certainly Staged , in: PetaPixel of October 1, 2012, last accessed May 25, 2019.

- ↑ a b c "The majority of photographic stories require a certain amount of setting up, rearranging, and stage direction to bring pictorial and editorial coherency to the pictures," here quoted from Kobré, Photojournalism , p. 402.

- ↑ Craig Hartley / BJ Hillard, The Reactions of Photojournalists and the Public to Hypothetical Ethical Dilemmas Confronting Press Photographers , University of Texas, Austin, 1981, cited here from Kobré, Photojournalism , p. 409.

- ↑ "Dammit, lady, this is history", Scott Harrison, From the Archives: Boris Yaro covers the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy , in: Los Angeles Times of June 4, 2018, last accessed May 25, 2019.

- ↑ World Press Photo Awards. Dispute about the suffering image , in: Spiegel Online from May 14, 2015, last accessed on May 25, 2019.

- ↑ Kobré, Photojournalism , p. 435.

- ↑ "The recent controversy over image toning is symptomatic of the current state of photojournalism and its place in a society that has learned not to trust what it sees," according to Laurent in his analysis published in the British Journal of Photography , quoted here from Kobré, Photojournalism , pp. 435f.

- ↑ Press photo 2005: "This picture has everything" , in: Focus Online from February 10, 2006, last accessed on May 26, 2019.

- ↑ History at the World Press Photo Foundation website, last accessed May 26, 2019.

- ↑ Historien om PF on the Pressefotografforbundet website, last accessed on May 26, 2019.

- ↑ About at the National Press Photographers Association website, last accessed May 26, 2019.

- ↑ NPPA Code of Ethics at the National Press Photographers Association website, last accessed May 18, 2019.

- ↑ About us on the Freelens website, last accessed May 26, 2019.

- ↑ About on the Lens Photo Prize pages, last accessed May 26, 2019.

- ↑ Who are we? on the website of impressum Photojournalists, last accessed on May 26, 2019.