Hanau City Palace

The Hanau City Palace (also called the Old Town Palace or later the Electoral Palace ) was the residential palace of the Counts of Hanau and later a secondary residence of the Electors of Hesse-Kassel . It emerged from a medieval castle complex , which was demolished with the exception of a few remains in the 19th century. The castle was badly damaged in World War II and then largely demolished. Therefore only a few outbuildings of the former residence have survived. While there are only sparse sources for the appearance of the medieval castle, the various stages of construction from the 16th century onwards can be reconstructed from documents and older views.

location

The city palace was located in the southern area of today's palace garden , north of the city hall and on part of the site on which the Karl Rehbein School stands today, at an altitude of about 104 m above sea level. NN. The Kinzig describes a wide arc from east to south and includes the castle area.

Building history

middle Ages

In the 12th century, the Lords of Hanau-Buchen had a moated castle built on an island that was surrounded by small arms in the Middle Ages . The builder is Dammo von Hagenowe, who is mentioned for the first time in a Mainz document in 1143 . The closest place was the later deserted Kinzdorf . In the years after 1170, the lords of Hanau-Dorfelden took over the castle. In the meantime people had already settled in the vicinity of the castle, the beginning of the village and later city (since February 2, 1303) Hanau .

The castle itself was first mentioned in a document in 1234 as "Castrum in Hagenowen". "Hagenowe" was the name given to the forest surrounding the castle . Little is known of the building history of Hanau Castle in the Middle Ages. Archaeological excavations in 2001 and 2002 uncovered parts of the retaining wall of the moat, which was founded on a wooden grate made of oak . This could be dendrochronologically dated to the year 1302.

With Reinhard I , the lords and (since 1429) counts of Hanau , later Hanau-Münzenberg , took over Hanau Castle. In the course of the 15th century it became their main residence, which was previously located in Windecken Castle for a while .

Modern times

In 1528, under Count Philipp II von Hanau-Münzenberg, the re-fortification of the city and castle Hanau began using a new fortification system theoretically conceived by Albrecht Dürer , which was actually built here for the first time. The moat between the castle and the outer bailey was filled and leveled, creating an inner courtyard, which later became the “small courtyard”. The work lasted until around 1560 in the reign of Count Philip III. inside.

From the 16th century, the standard of living in the medieval castle no longer met the expectations of its residents: The castle was gradually expanded into a palace, with Count Philipp Ludwig II (1576–1612) particularly prominent. From 1604 to 1606, a new Kanzleibau was built (which was later integrated into the Princes) and a portal building with doppelgeschossigem bay window above the gate entrance, the so-called Erkerbau , in the Renaissance style. The upper part of the former keep was modernized and decorated with a three-storey roof crown.

Larger plans by Philip Ludwig II, such as changing the complex to a Renaissance castle with a rectangular floor plan, were not implemented. His early death and the Thirty Years' War that began shortly afterwards prevented this. A plan for these conversions has been preserved in the Hessian State Archives in Marburg , which is not easy to interpret. Apparently the plan was to build a rectangular wing in the north of the complex. The pigeon tower would have been integrated into this despite the different orientation, while large parts of the core castle with the keep would have been removed. So it was limited to adding a wing to the northwest of the main castle, which largely consisted of half-timbered buildings and can be seen frontally on the Merian engraving.

Baroque

Even reconstruction measures in the baroque era did not lead to a uniform system. Rather, the wings of the castle formed an irregular ensemble. Count Philipp Reinhard von Hanau-Münzenberg (1664–1712) began to redesign the residential palace in a contemporary way. Since in 1701 he also laid the foundation stone for the Philippsruhe Palace, which was later named after him, the construction work on the city palace was rather cautious. First, from 1685 to 1691, another office building was built in the southern courtyard facing the city (used as the city library from 1953 to 2015), one of the few buildings in the complex that has survived to this day. Living rooms have been set up in the north wing of the palace, the previous office building. Count Philipp Reinhard had a stables built on an area next to the castle, which had been used as a garden until then , which was only completed in 1713 under his brother and successor, Johann Reinhard (1665–1736). The architect was Julius Ludwig Rothweil , who also designed the plans for Philippsruhe Palace. The bridge over the moat had to be relocated due to the construction of the Marstall and replaced with a new one.

Johann Reinhard, the last count from the Hanau family, had the north wing of the castle extended in an easterly direction. In addition, the prince's building received a representative portal with a pair of columns on both sides and a balcony above . From 1723 to 1728 Johann Reinhard had the moat backfilled and a new coach house built east of the Marstall , which later became the Friedrichsbau under the reign of Landgravine Maria von Hessen-Kassel (1723–1772), regent of the County of Hanau-Münzenberg from 1760 to 1764 was rebuilt. This wing of the building was roughly where the Karl Rehbein School is today. Landgravine Maria also had the palace gardens laid out in 1766 .

In 1732 the government building was extended to the south and, like the prince's building, got a mansard roof . Also under Landgravine Maria, the widow's palace was built, which was later used as the palace's financial courtyard and until 1945 as the building construction department . With these new buildings, the Hanau City Palace had reached its greatest extent at the end of the 18th century. After the death of the last count from the House of Hanau, the county of Hanau-Münzenberg with its capital Hanau fell to the Landgraviate and the later Electorate of Hesse . The castle occasionally served as a secondary residence for members of the landgrave, later electoral family. From 1786 to 1792 it was the widow's seat of Landgravine Philippine , the second wife of Frederick II of Hessen-Kassel, a born princess of Prussia from the Brandenburg-Schwedt branch line . She provided the palace with luxurious furnishings in the latest taste, which she took to her new palace in Berlin after 1792.

During the episode of the Grand Duchy of Frankfurt , to which Hanau belonged for a few years, the Hanau City Palace was the venue for the only meeting of the Grand Duchy's Estates , which opened on October 15, 1810.

From the beginning of the 19th century to the Second World War

In 1829/30 the medieval part of the complex, the original castle, was demolished under Elector Wilhelm II to create more space for the castle garden and a carriage house. The medieval parts no longer corresponded in any way to the intended use of the 19th century and the historical aspect of the complex did not count for Wilhelm II.

In 1866 the Electorate of Hesse was annexed by Prussia and the state no longer needed the palace as a residence. In 1890 the city of Hanau bought the castle. Apartments and offices were built in the Fürstenbau and Friedrichsbau. From 1927 the mayor's official apartment was also located in the Fürstenbau. The Museum of the Wetterau Society for Natural History has moved into the former office building . In addition, the city palace temporarily housed a post office , the Chamber of Commerce , a music academy, a pharmaceutical factory , the registry office and, from 1942, the museum of the Hanau History Association .

In 1928 the Marstall was converted into a town hall. The most striking structural change on the outer facade was a sandstone gable, which was faded in as the new main entrance on the narrow side of the building facing Schlossplatz . The town hall could be used for events, concerts, theater performances, exhibitions, conferences, slide shows and film presentations. After the National Socialists came to power , they staged the first co- ordinated city council meeting there on March 28, 1933 as a National Socialist rally in the great hall. During the Second World War it served as a hospital .

destruction

On January 6, 1945, the city palace and the city hall were destroyed in a bombing raid by the Royal Air Force and in another attack on March 19, 1945 . A part of the collection exhibited in the museum of the history association was also burned. After the war, only the town hall and the office building were rebuilt. The town hall was reopened on December 16, 1950. The city palace, of which the outer walls were preserved, was, like some other badly damaged, important historical buildings in the city center of Hanau, such as the baroque armory , the baroque city theater on Freiheitsplatz and the Edelsheim Palace , but was torn down, although there were votes, for example on the part of the history association to maintain the Fürsten- und Friedrichsbau. The official reason was that given the limited living space, people could settle down comfortably in the burned-out ruins. But only the outer walls of the castle buildings stood. In fact, the aversion of the local government at the time to the remnants of a past classified as useless, with which one no longer identified, and the completely opposite goals of the architecture of the time may have been a driving force. Very soon the city built “modern” and functional buildings like the Karl-Rehbein-School and the community center annex to the town hall. The Hanau politician Heinrich Fischer is said to have boasted with the saying: "We have removed the traces of feudalism".

In the years 2001 to 2003 the town hall was completely renovated, incorporated into a new congress center (Congress Park Hanau / CPH) and provided on its south side with a modern porch, which, although largely made of glass, has the historical facade and the richly decorated baroque Most of the sandstone portal of the southern gate is covered. Nevertheless, the town hall is a cultural monument according to the Hessian Monument Protection Act . The community center was demolished and replaced by the modern development of the CPH.

building

Medieval castle

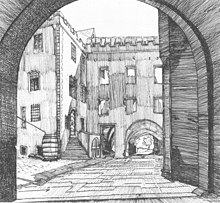

The original moated castle probably consisted of the typical buildings of a castle founding of this time: defensive wall and moat, gate protected by a drawbridge, palas , keep and farm building. Similar residences in terms of design are the castles of Babenhausen , Büdingen and Erbach , which also emerged from medieval complexes . Since the complex emerged from a small moated castle, numerous alterations were made over the centuries, during which the inner courtyards were almost completely built over. The narrow space in the inner courtyards of the castle is evident in numerous engravings. Drawings of the inner courtyards, which were made shortly before the demolition in 1829, show at least two narrow gateways in the inner castle.

Keep

The most striking part of the medieval castle complex was the keep (also called Heidenturm ) in the inner courtyard. For a long time, the tower was the tallest building in the city and the centerpiece of the medieval complex. It is unclear whether it had a hexagonal or octagonal floor plan. There are plans and views for both versions. The earliest city views around 1600 already show it with a three-storey crown and domed roofs, which it received during a renovation in 1605 under Count Philipp Ludwig II. One can only speculate about the earlier form of the upper degree. Due to the height and area, it could have been a butter churn tower . Views from the inner courtyard show that after the renovation at the beginning of the 17th century, it had brickwork made of bossed ashlars and, in the lower part, architectural decorations in the form of shell-crowned niches. In later times the tower had a tower clock. When it was demolished in 1829, attempts were made to at least preserve the tower, but a petition from Hanau's citizens was unsuccessful. The clock tower was translocated and at the end of the 19th century in the tower of St. John's Church built.

Archive tower

In the east of the core castle was the second largest tower (also pigeon tower ), which strengthened the castle on the field side. It is likely to have been the oldest part of the castle next to the keep and connected the residential buildings of the castle, which converged at an obtuse angle, on the northeast side. The Hanau archivist Johann Adam Bernhard notes that he found the year 1375 on it. Later engravings show it with a steep gable roof and a small bay window, probably a toilet shaft. The name archive tower shows that the count's archive was stored in the tower vault for a long time, possibly in the time before the construction of the new office building.

Martin's Chapel

The existence of a castle chapel is mainly revealed from written sources. It is unclear whether it was built when the castle was founded in the 12th century, as a Martin's altar was first mentioned in the castle in 1344, and a Martin's chapel in 1399. It was located to the east of the entrance to the inner courtyard in the vicinity of the later oriel building. The only illustration is a color drawing by the court architect Julius Eugen Ruhl . The interior of the chapel (1829), partially broken off, can be seen on it. Bar holes in the wall suggest that a gallery existed. The part of the ceiling that has not yet been torn off contains a late Gothic reticulated vault, which is closed at the bottom by the coats of arms of Hanau and the Palatinate. So it comes from the time of Philip III. (1526–1561) and his wife Helena von Pfalz-Simmern . The console stones standing on the floor bear the ancestral coat of arms of Helene and the coat of arms of Adriana von Nassau-Dillenburg , wife of Philip the Younger (1449–1500). The parts of the chapel visible in the picture are likely to date from this period.

When the Lutheran Count Friedrich Casimir von Hanau took over the government in the reformed county of Hanau-Münzenberg in 1642, the Martinskapelle was initially the only place in the county where the new sovereign was allowed to worship Lutheran by his reformed subjects. This stipulated a contract between the sovereign and the reformed elite of the Neustadt Hanau and made it possible for Friedrich Casimir to take office in Hanau in the first place. In 1658 the Lutheran Johanneskirche could be built.

Bay building

The so-called bay window (completed in 1610) replaced the previous inner castle gate under Count Philipp Ludwig II. The inner ditch was leveled (probably as early as 1528). The bay building stood on the site of the former forecourt and the courtyard room. The construction plan is preserved in the Hessian State Archives in Marburg . The Count wished that "the time over thor be a bay window (to) , as wide as it is Thor." A pen and ink drawing of the architect Johann Caspar Stawitz shows the Erkerbau from the passage through the upstream Fürstenbau while suspended 1829/30 . A two-wing, three-story building can be seen on it, in which the entrance to the courtyard of the palace was located in the middle. Above the gate there is a wide, two-storey bay window that connects the two wings that converge at an obtuse angle. The roof is accentuated to the right and left of the bay window by dwelling houses . There are scrollwork decorations on the mid-houses and the transitions of the building.

Residential buildings

The individual residential buildings of the medieval castle complex are difficult to identify. On the one hand, this is due to the numerous renovations that led to the inner courtyards of the core castle becoming narrower and narrower over time. On the other hand, there are few views of the rear (northeastern) area of the castle. The numerous conversions show that the increase in power of the Hanau Counts also meant an increasing need for space and that the complex only rarely met the expectations of its residents.

Outer bailey

Determining the location of the outer bailey is not easy because of the numerous modifications to the palace complex. Outside the main castle with the two inner courtyards, the area directly south initially seems to have fulfilled these functions. After the new city fortifications were built in 1528, another forecourt was added to the west. This western entrance was apparently closed again as early as 1634, possibly as a result of the siege of Hanau in the Thirty Years War. With the expansions under Philipp Ludwig II, the castle reached into the northern areas of the old town. The chronicle of Johann Adam Bernhard mentions a brewery and a bathhouse next to the old office. In the west of the outer bailey was the Count's Fronhof. A guard building stood in front of the new office building from 1829 to 1886, which can be seen on a lithograph from around 1870.

In the High Middle Ages, the Burgmannen houses of the low-nobility Burgmannen are documented here . These include numerous well-known names, which allows conclusions to be drawn about the importance of the Hanau Counts in the Wetterau: von Breidenbach , Bellersheim , Carben , Dorfelden, Riedesel , Hulzhofen , Heusenstamm , Spechte von Bubenheim, Hadersdorf, Kronberg , Buches and Reifenberg . The so-called castle freedom is likely to have taken up a considerable part of the old town due to the associated farmyards of these Burgmannenhäuser, up to today's Johanneskirchgasse and Johanneskirchplatz. The property of the castle freedom were from the administration of the old town Hanau independent fiefs of the sovereign.

Modern lock

Princely building

In 1713, while the Count's Philippsruhe Palace was being built in Kesselstadt, Count Johann Reinhard III. - perhaps by Christian Ludwig Hermann - build a long residential and palace building in place of the old outer bailey. A cellar building in the east was integrated into the prince's building and adjusted to the height of three storeys, and a small risalit was also created in the west of the complex because a transverse building of the outer bailey was integrated there. The three-story building met the old cellar building at an obtuse angle. The central entrance gate in the building served as a link, and until 1830 also the passage to the older parts of the castle. Ornamental pilaster strips made of bossed ashlars emphasized the small central projections. On the park side there were two columns next to the portal, on the city side there were four, and above them a balcony. After the medieval castle buildings were demolished, the prince's building formed the end of the castle square and the castle park. For this reason, after the destruction in 1945, attempts were made to preserve at least this building. The city had the ruins removed in 1956.

Friedrichsbau

The Friedrichsbau, completed in 1763 under the tutelage government of Landgravine Maria, was located east of the Marstall and formed a U-shaped continuation of the prince's building to the south. A coach house had previously stood in its place . Both buildings have a similar floor plan, the remise was probably included in the renovation, as it had stables and rooms for the staff. Even after the renovation, the Friedrichsbau was only two-story, but it received a high mansard roof. Photos show quarry stone masonry made of basalt similar to the Princely Building and the Chancellery. Here, too, the door and window frames were made of sandstone. Overall, the buildings of the city palace were simple. An essential difference to the city buildings becomes clear on old photos: the city palace was mostly covered with slate, while brick was used almost entirely for the buildings in the old town.

As before the Remise, the Friedrichsbau did not have a cellar. During the excavation for the new Karl Rehbein School in June 1956, a wooden pile grid was discovered under the Friedrichsbau. There was water ingress in the excavation pit itself. Obviously this part of the castle was built on a filled-in arm of the Kinzig. The wood therefore survived the centuries due to the preservation of moist soil .

Stables

The Marstall is a former baroque riding arena (1711/13), which was built according to a design by Julius Ludwig Rothweil and converted into an event hall ("town hall") in 1928. During this renovation, it received a new sandstone portal with the Hanau coat of arms in the style of the time. After the war ruins of the prince's building had been demolished, a functional extension was added to the north ("community center"), which had to give way in 2001 to the new Congress Park Hanau (since 2003), a congress and event center, due to the impact of branches . The Marstall was also included in this Congress Park Hanau , redesigned again and given a modern accompanying building. An extended stage building was added to the eastern narrow side, so that the historical facades are now all clad with modern parts of the building. As a result, the portal on the south side of the stables made of reddish sandstone, on whose pilasters various riding implements are attached, is difficult to see. The Hanau-Lichtenberg coat of arms is located above the gate.

Chancellery building (former city library)

The former office building was built between 1685 and 1691. The architect was Johann Philipp Dreyeicher . It has been used culturally since the 19th century. Until 2015 it housed the Hanau-Hessen city library with its regional history department, the Hanau city archive, and since 1868 the Wetterau Society for Natural History and the Hanau History Association . These are now housed in the Forum Hanau . The building is made of dark basalt rubble. Window and door reveals are made of red Main sandstone. But the building was apparently plastered in earlier times, as old views show. The office building initially had a simple gable roof and was only covered with a mansard roof during the construction of the Marstall. Today it has a gable roof again. Above the entrance is the double coat of arms of Count Philipp Reinhard and his wife, Countess Palatinate Magdalena Claudia von Pfalz-Zweibrücken-Birkenfeld-Bischweiler (1668–1704), above the year 1691 (completion of the building). The portal was created by the stonemason Andreas Neubau from Ortenberg .

Water tower

The water tower is the last remaining fortification tower to protect the castle and city of Hanau. It was the connecting piece between the castle, outer bailey and city fortifications and got its name from its location in the water of the castle and city moat. The water tower was probably built in the 14th century together with the city fortifications first mentioned in 1338. From 1543 to 1829 at the latest, it served partially as a military prison, and since 1962 it has housed parts of the city archive. On its east side, the cross-section of the former city wall and its battlement can still be read in the masonry . Today's roofing probably comes from the baroque period. The water tower is the last building of the former castle that still has medieval structures.

Fruit storage

The former count's fruit store is in the courtyard behind the office building (so-called Fronhof ). The time of its construction cannot be specified, the Fronhof is first mentioned in a document in 1457. The building, known today as the “Fruchtspeicher”, probably dates from the late 17th century. The gendarmerie has been located there since 1872. During the Nazi dictatorship there was a police prison here, the starting point for the kidnapping and later murder of many.

Found objects

The two demolitions in 1829 and 1945 have left little evidence of the castle. This also applies to the collections of the Hanau History Association, which were destroyed in 1945 and which kept many of the architectural parts that were still preserved. In the Historical Museum Hanau four iron, ornate stove tiles and an ornate iron door from the City Palace are exhibited. Furthermore, a showcase shows finds from archaeological excavations in the area of the moat.

Finds from archaeological excavations in the area of the city palace in the Hanau Historical Museum

literature

- 675 years old town Hanau. Festschrift for the city anniversary and catalog for the exhibition in the Historical Museum of the City of Hanau am Main , ed. from the Hanauer Geschichtsverein e. V., Hanau 1978, ISBN 3-87627-242-4 .

- Heinrich Bott : The demolition of the old castle in Hanau and other things about the Hanau city castle. In: New Magazine for Hanau History 3, Hanau 1955–1959, pp. 59–65.

- Heinrich Bott: The old town of Hanau. Building History House Directory Pictures. A memorial book for the 650th anniversary of the old town of Hanau. Hanau 1953.

- Heinrich Bott: Contributions to the building history of the castle in Hanau. In: Hanauer Geschichtsblätter 17. Hanau 1960, pp. 49–72.

- Heinrich Bott: City and fortress Hanau. In: Hanauer Geschichtsblätter 20. Hanau 1965, pp. 61–125.

- Rudolf Knappe: Medieval castles in Hessen. 800 castles, castle ruins and fortifications. 3. Edition. Wartberg publishing house. Gudensberg-Gleichen 2000, ISBN 3-86134-228-6 , p. 391f.

- Karl Ludwig Krauskopf: 150 years of the Hanau History Association. Festschrift for the 150th anniversary of the association (Hanau 1994).

- Carolin Krumm: Cultural monuments in Hessen - City of Hanau. Ed .: State Office for Monument Preservation Hessen. Wiesbaden 2006, ISBN 3-8062-2054-9 .

- Frank Lorscheider: Interim report on the excavations in the area of the Hanau City Palace . In: New Magazine for Hanau History 2002 / I, pp. 3–20.

- Fried Lübbecke : Hanau. City and county. Cologne, 1951, p. 269ff.

- Christian Ottersbach : The castles of the lords and counts of Hanau (1166–1642). Studies on castle politics and castle architecture of a noble house. Ed .: Magistrat der Brüder-Grimm-Stadt Hanau and Hanauer Geschichtsverein 1844 eV , Hanau 2018, ISBN 978-3-935395-29-8 (= Hanauer Geschichtsblätter vol. 51 ), pp. 421-483.

- From the Residenzschloss to the Congress Park. The (de) transformations of the Hanauer Schlossplatz . Ed .: Hanauer Baugesellschaft GmbH. Hanau 2003.

- August Winkler and Jakob Mitteldorf: The architectural and art monuments of the city of Hanau. Festschrift for the 300th anniversary of the founding of the Neustadt Hanau. Hanau 1897.

- Ernst Julius Zimmermann : Hanau city and country. 3. Edition. Hanau 1919. ND 1978, ISBN 3-87627-243-2 .

Web links

- Renaissance castles in Hesse (project at the Germanic National Museum by Georg Ulrich Großmann )

- Descriptions and site plan of the Marstall as well as the office building, water tower and fruit storage on DenkXWeb of the State Office for Monument Preservation Hessen.

- Illustration by Daniel Meisner from 1626: [Castle] Hanaw. Ars dulcis vitae nutricula ( digitized version )

Individual evidence

- ^ Günter Rauch: "Tammo de Hagenouwa". When the name Hanau was first mentioned in a document 850 years ago. New magazine for Hanau history 1993, 4 ff.

- ↑ See H. Bott: City and Fortress Hanau (III). Hanauer Geschichtsblätter 24, 1973, p. 19.

- ↑ New building plan .

- ↑ KL Krauskopf 1994, figs. 59–61 - pictures from the collection at that time.

- ↑ The discussion of that time is documented in detail in KL Krauskopf 1994, 248-262 (with further sources); Gerhard Bott : "Modern building" in the city of Hanau 1918–1933. "Demolition crime" and reconstruction after 1945 . In: Hanauer Geschichtsverein (ed.): Gerhard Bott 90 . Cocon, Hanau 2017. ISBN 978-3-86314-361-9 , pp. 85-113 (104-106).

- ^ Gerhard Bott : "Modern building" in the city of Hanau 1918–1933. "Demolition crime" and reconstruction after 1945 . In: Hanauer Geschichtsverein (ed.): Gerhard Bott 90 . Cocon, Hanau 2017. ISBN 978-3-86314-361-9 , pp. 85-113 (106).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i The source for the descriptions of the no longer preserved buildings was the catalog "675 Years of Hanau Old Town." (See list of literature), especially the old views it contains. Pp. 209–215, cat.-no. 90-104. Numerous plans and other views can be found from the various construction periods at Zimmermann 1919 (see list of literature) pages 1a, 1c and 1d, between pages 312 and 313.

- ↑ Plans in Zimmermann 1919, sheets 1a, 1c and 1d, between pp. 312 and 313.

- ↑ in detail in Bott 1953 (see literature list)

- ↑ The list follows the Bernhard Chronicle, Chapter 5 § 14.

- ↑ Bott 1953

- ↑ Lübbecke, p. 271.

- ↑ a b c Descriptions of the preserved parts of the city palace can be found in Krumm: Kulturdenkmäler.

- ↑ Lübbe, p. 270.

- ^ Christian Ottersbach: The castles of the lords and counts of Hanau (1166–1642). Hanau 2018, p. 439.

- ↑ Bott 1953 (see list of references), p. 20.

Coordinates: 50 ° 8 ′ 17.2 ″ N , 8 ° 55 ′ 7 ″ E