Riots in Bangkok 2010

The riots in Bangkok in 2010 were the events surrounding the protests of the National United Front of Democracy Against Dictatorship ( UDD for short , German: United National Front for Democracy Against Dictatorship ; popularly red shirts ) against the Thai government under Prime Minister Abhisit Vejjajiva . The UDD demanded the resignation of his cabinet and immediate new elections. Demonstrators occupied the Bangkok business district of Silom for weeks , erected barricades and fought with the police and the army.

The unrest began with mass demonstrations on March 12, 2010. After the red shirts entered the House of Representatives in early April , the government established the Center for the Resolution of the Emergency Situation (CRES) and declared a state of emergency in Bangkok and several Thai provinces. As a result, the demonstrations escalated into street fighting until the Thai Armed Forces violently suppressed them on May 19. The government extended the state of emergency several times and lifted it on December 22nd.

Between 88 and 92 people died in the riots. The estimates of the number of injuries vary between just under 1,900 and more than 2,000. There was considerable damage to property, both directly as a result of the fighting and the subsequent arson and indirectly as a result of a loss of income in tourism.

Most of the international community reacted with concern about what had happened but refrained from taking any concrete steps. Many countries, including Germany and Austria, issued travel warnings for Thailand. Several non-governmental organizations criticized the government and the UDD's actions.

Following the protests, the authorities arrested several red shirt leaders and charged them with terrorism and libel charges . This was followed by complaints from the public prosecutor's office against Abhisit Vejjajiva and the then Interior and Deputy Prime Minister Suthep Thaugsuban in December 2012.

On the anniversaries of the start of the protests, the first violent clash and the storm by the security forces, peaceful commemorative demonstrations by the UDD took place in Bangkok, each with around 20,000 participants.

In the parliamentary elections in July 2011 , the red-shirted Pheu-Thai Party (PTP) won an absolute majority, while Abhisit Vejjajiva's Democratic Party only achieved 30 percent and subsequently had to give up power.

In August 2013, the new government started a debate in the House of Representatives to pass an amnesty law that would guarantee participants in political protests impunity.

background

prehistory

The events were preceded by a political crisis in Thailand triggered by a bloodless coup against the then Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra in September 2006. The military justified the coup with allegations of corruption surrounding the sale of his communications group Shin Corporation , for which he paid no taxes thanks to changes in the law.

A few weeks after the coup, the UDD was founded, which had close ties to the ousted head of government. Popular parlance and the press often referred to the party as "red shirts".

A group under the aegis of the military developed a draft constitution , which the people adopted in a nationwide referendum in August 2007 with around 58 percent of the vote. As a result, free elections took place in December, from which the Phak Palang Prachachon (PPP), a successor to Thaksins Thai Rak Thai (TRT), emerged as the winner under Samak Sundaravej . At the end of August 2008, several thousand protesting supporters of the People's Alliance for Democracy (PAD; the so-called "yellow shirts") occupied his official residence for several days and temporarily occupied the two airports in Bangkok ( Suvarnabhumi and Don Mueang ) and the airports in Phuket , Krabi and Hat Yai . Members of the union and the pension funds also went on strike by rail connections to Bangkok, which ultimately led to the resignation of the government. In December 2008 , after banning the PPP, Parliament elected Abhisit as prime minister.

After hundreds of red shirts stormed the conference venue, the ASEAN summit in Pattaya , Thailand had to be canceled in early April 2009 . Prime Minister Abhisit Vejjajiva then declared a state of emergency. The political unrest also spread to Bangkok, where two people were killed in street fights with police and soldiers.

Regional imbalance

Map of the percentage of the poor in the population in the provinces of Thailand in 2002 according to a study by the World Bank. <7.4% 7.4–14.2% 14.2–24.9% 24.9–35.2% > 35.2% |

Bangkok has traditionally been the power and administrative center of Thailand. Initially, it benefited primarily from trade with China. Between 1985 and 1996, the industry in Thailand boomed , among other things due to a massive inflow of investment capital . During that time, the export volume increased twelve-fold, and an urban middle class emerged, while agriculture lost its importance. In 2002, 40 percent of Thailand's economic output was concentrated in Bangkok, but only 9.5 percent of the population. Wages were about ten times higher than the rest of the country. At the same time, the urban population grew rapidly. It grew by four million people between 1984 and 1996, most of whom came from the far poorer areas in northeastern Thailand.

Developments in northeastern Isan , on the other hand, were completely different, as they mainly generate their income from agriculture. This determined the country's exports until the 1970s, which changed significantly afterwards. A stagnation in farm production contrasted with an annual 15 percent growth in industry. Because of the better employment situation, many Thai people originally working in the agricultural sector migrated to Bangkok as seasonal workers. Most of them planned to return to their families when they had made enough money, which is why they did not consider the city their home. In 2008, the World Bank registered 88 percent of Thais living in poverty in rural areas, with around half concentrated in the northeast of the country. Due to its large population, around a quarter of the parliamentary seats go to the region in elections.

The difference between the populous but politically and economically underrepresented Isan and northern Thailand compared to the urban and touristy central Thailand and the south created a simmering conflict in Thai society. While the rural areas largely determined the outcome of the election through the bulk of the population, the elites were in the cities, which manifested itself in the economy and education. These differences became clear for the first time in the election victory of Thaksin, who, although a billionaire himself, had his power base mainly in the poorer northern and rural areas, which he achieved with a noticeable improvement in the health system, with the granting of small loans, with the One Tambon One Product business development project (OTOP) and the expansion of the infrastructure. However, critics accused him of having done this out of power politics. The military overthrew him in a non-violent coup in 2006 and charged him with corruption, after which he fled abroad.

The People's Alliance for Democracy, on the other hand, wanted 70 percent of the MPs to be appointed by the royal family. With little support outside of Bangkok, observers questioned the PAD's ability to win elections.

Position of the royal family

King Bhumibol Adulyadej , who does not exercise any specific power to govern, is traditionally considered an integrating figure in Thailand. The population appreciates and adores him to a great extent. In the past, he usually took a mediating stance in political crises, but since the end of 2009 he has spent most of his time in hospital due to shortness of breath.

The royal family as a whole sent contradicting signals. During the 2008 protests, the Queen attended the funeral of a PAD member who was shot by the police and was therefore suspected of being partisan. On the other hand, the royal family announced that it would cover the funeral costs of the red shirt military advisor Khattiya Sawasdipol, who was shot by a sniper during the occupation .

Red shirts

composition

For the University of California , Naruemon Thabchumpon and Duncan McCargo examined the social composition of the protesters between March 15 and May 20. To do this, they conducted 400 interviews, including with many red shirt functionaries at the community level, at the centers of protest and interviewed 57 opinion leaders of the UDD. The demonstrators often worked in agriculture and owned an average of six acres of land. A large proportion of the red shirts were made up of migrant workers who lived in Bangkok most of the time but chose to live in their home villages. The majority of those questioned were between 40 and 60 years old and could still remember the time when electricity and television made their way into the villages. About a third of the demonstrators had only elementary education, a third were in secondary school, and the remaining third were college educated. Over 40 percent earned more than 10,000 baht a month, and about 30 percent had to get by on less than 5,000 baht. For comparison: In 2010 the statutory minimum wage per day was between 151 baht in Phayao , Phichit , Phrae and Mae Hong Son and 206 baht in Bangkok and Samut Prakan, depending on the province .

Most of the opinion leaders surveyed referred to themselves as farmers, but usually ran a business and had various sources of income. In addition, there were an above-average number of radio presenters and regional politicians among them. More than ³ / 4 benefited from various subsidies from the time of Thaksin Shinawatra, and all were beneficiaries of the health program from that era. In addition, a large proportion of them said they received allowances from relatives working abroad.

Management structure

The best-known members of the leadership structure of the UDD were the former general secretary of the Democratic Party and deputy interior minister in the 1980s, Veera Musikapong , the former member of parliament Jatuporn Prompan and the former government spokesman Nattawut Saikua .

These professional politicians contrasted with various academic and social figures in the movement. These included the university lecturer and human rights activist Jaran Dithapichai and the medical doctor and former leader of the 1992 democracy movement, Weng Tojirakarn . Wisa Khantap worked as singers and artists and participated in political campaigns, and Woraphon Phrommikabut formerly headed the Department of Sociology and Anthropology of the University of Bangkok .

The third group in the ruling class presented themselves as populist whips such as the former pop singer and activist of May 1992, Arisman Pongruangrong , the well-known radio presenter Kwanchai Praiphana , the former member of parliament Suporn Atthawong (also known as Rambo Isan ) and the comedian Yoswaris Chuklom (also known as Jaeng Dokjik ).

Members of the Thaksin Shinawatra family, including his sister and later Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra , and a group within the UDD called Red Siam were considered to be hard-line representatives . The official leader of this group was Jakkrapop Penkair , who lived in self-chosen exile , and Surachai Danwattananusorn acted as its figurehead domestically . In addition, a military faction around the former Major General Khattiya Sawasdipol (also known as Seh Daeng ) appeared as hardliners.

As a lesson from the failed protests of 2009, the movement developed the motto of the three bans:

- ti fa ; do not attack the sky (by "sky" the traditional institutions of Thailand - like the monarchy - are meant)

- da tho ; do not engage in verbal attacks

- kokhwamrunraeng ; do not act violently

In practice, however, problems arose from this, since the UDD united a wide range of political currents in its ranks. The leaders included both former communists and those with nationalist attitudes. Sometimes they had fought each other in the 1970s. The various currents within the movement made political decision-making difficult. The fact that Thaksin Shinawatra was in exile and it was not clear which group had his support further complicated the situation. This fact was particularly evident when it came to the use of force.

organization

The red shirt movement organized itself mainly in a loose network structure. Autonomous local groups got involved in it and sent their own representatives to the protests. In the “ political schools ” that took place in the run-up to the protests , these organizations developed their own action plans and strategies and coordinated with one another. Schools provided key contacts during the recruiting phase, but lost influence as the fighting increased. More than half of the graduates left the protest centers after the outbreak of violence during the first eviction attempt on April 10th.

The protesters used radio stations, CD pressings and printed leaflets as their main means of communication. With the help of cell phones, they transmitted radio signals that were difficult to receive to the scene and sent mass text messages. The television station People's Television (PTV) also played an important role in the dissemination of information.

The central organizers provided food, stages, radio reception, and some large tents. They also paid a few thousand baht travel allowance per pickup (typically with 10 passengers), depending on the distance, for the travel expenses of the arriving red shirts. These stayed with the protests for about a week, and then she replaced a pickup truck with other members of the same group. This model was the most popular because it gave protesters the opportunity to continue to meet their work obligations. The red shirts who lived in Bangkok mostly attended the rallies in the evenings. Some paid other UDD members to participate or pooled money to support a pickup together. There were also rumors of rally members' debt cancellation following a renewed takeover by Thaksin Shinawatra. None of the respondents had to pay for food or fuel to participate in the protests. Many of the visitors from the provinces used their stay in Bangkok for sightseeing and visited the Wat Phra Kaeo in the Grand Palace and the Bangkok Skytrain . Relatives and voluntary host families in particular offered overnight accommodation. Very few protesters stayed and slept there all the time.

Motivation and Goals

The vast majority of the demonstrators wanted to bring Thaksin Shinawatra back to power through their protest through democratic procedures. In her opinion, the Thai judicial system unilaterally favored supporters of the PAD and the Democratic Party. Some gave regional prejudices against the residents of northeast Thailand as a reason. Almost all respondents identified themselves as strong supporters of more democratic elections at all levels and defined themselves as opponents of the 2006 coup and the various political interventions by the courts. In their opinion, the Abhisit Vejjajiva government acted aloof and had no contact with the people.

When asked about their political views on foreign migrants, the demonstrators often described them as a danger, using conservative nationalist anti-Burmese rhetoric. The interviewees mostly associated the NGO scene in Thailand with “ romantic illusions ”.

Black shirts

Among the demonstrators was a group of people who were called “black shirts” or “men in black” regardless of the color of their clothes. They were militarily trained and heavily armed men who attacked security forces and civilians on various occasions. There are numerous recordings on which they in the use of AK-47 - and M16 - assault rifles are shown. In addition, they had M79 - grenade launcher . The black shirts mingled with the demonstrators and used them as cover. Small-group raid-like attacks carried out by them suggest training in military tactics. From where the "Men in Black" received their orders is not known.

Chronicle of events

Peaceful protests and first occupations

On March 12, 2010, red shirt protesters gathered in the capital, Bangkok , to pressure the Abhisit government. Two days later, around 150,000 protesters occupied the Phan Fah Bridge in the old town. On March 17, demonstrators spilled blood that had previously been put into containers in front of Prime Minister Abhisit Vejjajiva's official residence to symbolically make a sacrifice for democracy.

On March 29, two-day negotiations between the government and the protesters failed and the rallies were announced to continue. On April 3, red shirts occupied the Ratchaprasong intersection ("Ratprasong") in central Bangkok . This is located in the Pathum Wan district in the immediate vicinity of various shopping centers and hotels and should remain the center of movement until the security forces storm.

After protesters broke into the House of Representatives on April 7 and forced cabinet and parliament members to flee, the government established the Center for the Resolution of the Emergency Situation (CRES) with an extensive mandate to restore order to the country. It consisted of numerous high-ranking politicians, state officials and the military and was headed by Interior Minister and Deputy Prime Minister Suthep Thaugsuban .

state of emergency

The government declared a state of emergency on the evening of April 8th. This authorized the CRES to detain and question suspects for up to 30 days. The CRES staff were largely immune to law enforcement in these acts. The number of people detained was not disclosed.

In addition, during the time of the turmoil, the CRES shut down about 1,000 websites, a television station, several online television channels, and more than 40 radio stations that the government had linked to the UDD.

The next day, on April 9, protesters stormed the country's most important satellite station to allow the blocked red shirt television station, People's Television (PTV), to operate again.

When government troops failed to push back the demonstrators at Phan Fah Bridge on the afternoon and evening of April 10, they engaged in violent clashes with the demonstrators. The military and police stormed the occupied central business district. They encountered resistance from black shirts armed with assault rifles and grenade launchers. Activists also attacked them with pistols, slingshots and homemade explosives and incendiary devices. Strangers killed the commander of the troops, Colonel Romklao Thuwatham, with a grenade launcher and injured several of the officers standing with him. Romklao Thuwatham was known in advance because in April 2009 he led the military dissolution of the UDD protests in Bangkok at the Dindaeng intersection, subsequently defended the operation in front of parliament and accused the red shirts of violence. The military units panicked and deployed live ammunition. According to the government, 26 people died and at least 850 were injured. Among these were five dead and 350 wounded soldiers.

Police tried to arrest four red shirt leaders who were in a hotel on April 16. Among them were the spokesman Nattawut Saikua and the hardliner former singer Arisman Pongruangrong . The crowd of demonstrators present prevented them from storming the building, allowing those wanted to escape through the windows and over the facade. The red shirts, according to their own statements, took four members of the operating special police unit hostage. In the evening, Prime Minister Abhisit Vejjajiva announced the restructuring of the CRES, referring specifically to the failed arrest attempt. The commander in chief of the army, Anupong Paochinda , replaced the previous director Suthep Thaugsuban. In addition, the center should better prepare for terrorist threats.

King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital staff complained that armed red shirts ransacked the hospital daily between April 23 and 29, accusing the staff of cooperating with the government. Due to the disruptions, patients had to be relocated and most services had to be stopped.

Negotiations and escalation

Abhisit offered the demonstrators new elections on May 3rd as part of a five-point plan to take place on November 14th of the same year. As a condition, he called for the occupation to end immediately. The five-point plan also included recognition of the monarchy in Thailand, an investigation into the clashes in April 2010, and agreements on constitutional reform. The red shirts rejected the proposal the next day, citing the late election date. Meanwhile, the clashes continued and renewed clashes between police and protesters on May 7 resulted in deaths and injuries on both sides. Two days later, on Sunday evening, May 9th , a bomb made of fireworks exploded in front of the home of the then chairman of the electoral commission of Thailand , Apichart Sukkhakanont . An attack on a bank branch in Bangkok on the same day failed because the grenade used for it turned out to be a dud. People were not harmed in either of the two incidents.

The red shirts demanded prosecution of Deputy Prime Minister Suthep Thaugsuban on May 10 as a condition for a negotiated settlement. They accused him of ordering the violent use of soldiers and police on April 10, which resulted in numerous victims. He voluntarily presented himself to an official interrogation, but stressed that he could not be held responsible as a state of emergency was in effect at the time. The next day, the red shirts agreed in principle with the government's peace plan, but made numerous new demands that prompted the government to withdraw the offer. Prime Minister Abhisit issued an ultimatum and announced that the protests would be broken up by force at midnight.

The CRES changed the rules of engagement of its troops on May 13th . The new guidelines allowed the use of live ammunition for warning shots, for self-defense and for killing unspecified " terrorists ". According to Human Rights Watch , the government created no-go areas between the military and the demonstrators. Snipers were allowed to shoot anyone who was there.

On the same day, during an interview with foreign press representatives, a sniper met Khattiya Sawasdipol, a military leader of the insurgents. He died four days later from his severe head injuries. As a result, the situation escalated and shots and explosions of grenades could be heard around the city around the clock.

From May 15, the military tried to block the water and food supplies in the occupied district, but only partially succeeded. In addition, the CRES 106 blocked bank accounts of leading members of the UDD, former officials of the Thai Rak Thai, Khattiya Sawasdipol and the family of Thaksin Shinawatra. In clashes and civil war-like scenes, snipers fired on demonstrators who the government only referred to as terrorists. These in turn set fire to barricades made of car tires and returned fire from sharp and sometimes improvised weapons.

On Sunday, May 16, the police imposed a curfew on parts of Bangkok. The German embassy, located right next to the occupied territory, had to cease operations completely the next day. The government gave the red shirts another ultimatum until the afternoon after they rejected an offer for mutual withdrawal the day before.

Storm by the security forces

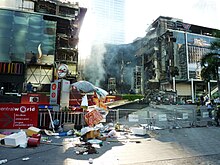

At 5 a.m. on May 19, the military stormed the neighborhood using armored vehicles, whereupon several red shirt leaders declared their preliminary surrender. Jatuporn Prompan , Weng Tojirakarn and Nattawut Saikua urged their supporters to stop the protests in order to avoid further losses. In contrast, some UDD leaders urged their supporters to launch a coordinated campaign of arson and looting if the area was stormed. As a result, fires broke out in the Central World (ZEN department store) shopping center , the second largest department store complex in South Asia, in the building of the television station Channel 3, in the stock exchange and in various bank branches. There were a total of 36 sources of fire in the city. Part of Central World burned out, and parts of that area collapsed as it progressed. The fire department found ten bodies in the rubble. Snipers fired from the Bangkok Skytrain , a suburban train on stilts, at protesters.

In addition to Bangkok, fighting also took place in the provinces of Khon Kaen , Ubon Ratchathani , Udon Thani and Mukdahan .

Thousands of UDD supporters fled to the Wat Pathum Wanaram temple , as it was considered a protected zone by an agreement with the government. Forensic evidence and eyewitness reports revealed by Human Rights Watch during an investigation, snipers opened fire on the refugees in the temple, killing six people and injuring many more.

On Thursday, May 20, the situation largely calmed down. The night curfew remained in effect. On the following Sunday, numerous Bangkok people gathered to support the city administration under the motto “Together We Can” (German: “Together we can do it”) in cleaning up the Lumphini Park and the Thanon Silom . Further clean-ups took place where the UDD had previously been blocked.

After the riots

Direct consequences

While the majority of the demonstrators were busied back to their homes and left in the dark about a possible charge, the government announced that it would report UDD leaders and Thaksin Shinawatra to charges of terrorism. On May 27, a week after the storm, around 300 demonstrators, including seven protest leaders, were detained. Prime Minister Abhisit promised a complete clarification of the events including the role of the security services. A British and an Australian were also charged with participating in the protests, one for inciting arson and the other for inciting violence on the main stage. The government requested the immunity of two MPs to be waived in order to be charged with terrorism. She also suspended four police chiefs in northern provinces for failing to prevent riots by UDD sympathizers in their area. A Bangkok court issued an arrest warrant for Thaksin on May 25, in response to a government motion that Interpol would enforce the warrant. Thaksin promptly denied the allegations.

The government accused militant activists of attacking security forces and civilians and presented numerous weapons that were found after the storming of the occupied area. Among other things, the authorities showed a vehicle full of grenades that had allegedly been discovered in front of the parking garage of the Maneeya Center. International press representatives stated, however, that the vehicle only appeared there on May 21, two days after the storm on the Ratschaprasong intersection. The government also showed video recordings of the red shirt leaders at the international press conference, in which Thaksin Shinawatra also appeared. She claimed that the insurgents had already set up armed troops (the so-called "black shirts") in advance.

state of emergency

Because of the risk of violent clashes, the government extended the state of emergency in 19 provinces, including Bangkok, until December 2010 on June 6.

On July 25, a bomb exploded in the April-occupied area, killing one man and injuring several people. Five days later, on July 30, a man was seriously injured in a bomb explosion. The explosive device was located in an avenue near the Victory Monument, which has several government buildings. The government officials stressed that the state of emergency could not be lifted because of feared activities by the red shirts. On August 27, a person was injured in an explosion outside a hotel and mall in central Bangkok.

After eight months, the government ended the state of emergency in Bangkok on December 22, 2010.

On April 22, 2011, an M79 shell struck a group of pro-government demonstrators, killing one person and injuring 85.

Follow-up demonstrations

On September 19, the first red shirt demonstration after the eviction took place in Bangkok. At the Ratchaprasong intersection, 6,000 demonstrators gathered according to the authorities and 10,000 demonstrators according to the organizers, raised red balloons and commemorated the coup against Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra in 2006. Hundreds of police officers watched the rally and went off peacefully.

On March 12, 2011, on the anniversary of the start of the demonstrations, tens of thousands of Thai people took part in a rally to commemorate the events. Again the security forces showed a strong presence. A year after the first violent clashes between police and red shirts, on April 10, around 20,000 people remembered the victims of the riot with a religious ceremony and a minute's silence. Thaksin Shinawatra videotaped the two rallies. Also on the first anniversary of the storm by the security forces on the occupied territory, May 19, 2011, around 20,000 red shirts demonstrated in Bangkok and held a funeral mass for those killed. All events were largely peaceful. Despite this, there were subpoenas and charges of libel against several speakers.

Criminal Investigations

The Department of Special Investigation (DSI) conducted the criminal investigations. On July 29, it passed the charges against ex-Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra and 24 other opposition leaders for violating anti-terrorism laws to the prosecutor. On August 12, the latter indicted 17 members of the opposition movement who, if convicted, faced the death penalty. In March 2011, the competent court released Nattawut Saikua from custody on bail.

After the unrest, Interior Minister Suthep Thaugsuban accused the activist Jatuporn Prompan of conspiracy to murder Khattiya Sawasdipol. Because of these allegations, the security forces arrested him on suspicion of terrorism. Jatuporn was released on bail on August 2, 2011. Two weeks earlier, the red shirt- affiliated Pheu Thai Party (PTP) won the 2011 parliamentary elections in Thailand .

In November 2010, the DSI announced that 12 of 18 deaths investigated so far were due to militant red shirts or their sympathizers. The perpetrators of the remaining six dead are unknown. Reuters news agency published internal DSI papers in December according to which unidentified persons shot at civilians at the Ratchaprasong junction from the Bangkok elevated railway in the Pathum Wanaram temple opposite on May 19, the day the area was evacuated.

During the New Year celebrations in mid-April 2011, the DSI initiated proceedings against ten speakers at the commemorative demonstrations on the anniversary of insulting the king and the monarchy. Among them were some who had been arrested by the security forces after the storm. On April 18, 2011, 18 UDD leaders were summoned by the DSI to investigate allegations of lese majesty , which is punishable by several years in prison in Thailand. Those affected were Weng Tojirakarn , Nattawut Saikua , Korkaew Pikulthong , Thida Thavornseth , Karun Hosakul , Yoswaris Chuklom , Wiputhalaeng Pattanaphumthai , Veera Musikapong , Chinawat Haboonpat , Wichian Khaokham , Suporn Atthawong , Kwanchai Sarakham (Praiphana) Nisit Sinthuprai , Prasit Chaisisa , Worawut Wichaidit , Laddawan Wongsriwong , Jatuporn Prompan and Somchai Paiboon . Later, Payap Panket was added to the list.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission

The Abhisit government established a " Truth and Reconciliation Commission " (TRCT) to investigate the incidents, headed by former prosecutor Kanit Nanakorn . Swiss forensics and ballistics experts advised the committee. There was criticism of the allegedly weak mandate and the ineffective witness protection. The commission was allowed to summon witnesses, but was not authorized to summon them .

The Commission published two interim reports and a final report on September 18, 2012. She saw it as proven that security forces had used war weapons against demonstrators. Contrary to government claims that the army only defended itself in self-defense and did not use snipers, the commission documented cases of civilians being shot in the head. She also assumed that Khattiya Sawasdipol was murdered by soldiers. According to the report, some of the demonstrators had cooperated with the black shirts who attacked soldiers with heavy weapons.

Both the army and representatives of the red shirts rejected parts of the final report. Human Rights Watch, however, praised the comprehensive investigation as a first in Thailand.

The commission encouraged reconciliation efforts to avoid future outbreaks of violence. She recommended a public apology from the government for failing to resolve the situation peacefully. Regarding a possible amnesty , she was cautious about the rights of victims. She also called on the army leadership not to interfere in politics and in particular to refrain from a coup . She advised the judiciary to withhold penalties for lese majesty against red shirts. In the recommendations, the commission further demanded that Thaksin Shinawatra should withdraw completely from politics. In the event of his return, Commission President Kanit Nanakorn feared renewed unrest.

Criminal proceedings against former members of the government

On December 13, 2012, the DSI filed murder charges against Abhisit Vejjajiva and Suthep Thaugsuban. According to the authorities, the indictment was based on testimony and a judgment and concerned the case of a taxi driver shot dead by soldiers. Both defendants pleaded not guilty. On December 12, 2013, the prosecutor general's indictment was approved by the competent criminal court. In addition to the murder of the taxi driver, it also included the murder of a 14-year-old boy and the assault of a minibus driver. Abhisit turned himself in and was released on bail. In August 2014, the Bangkok Criminal Court acquitted Abhisit and Suthep.

Amnesty Act

On August 7, 2013, the parliament debated an amnesty law that deals with the participants in the riots. The proposal, often referred to as “Worachai's Law”, was introduced by Worachai Hema , a parliamentarian of the ruling Pheu Thai party, and is intended to bring those who have participated in political protests since the military coup impunity. Specifically, it applies to incidents between September 19, 2006 and May 10, 2011. According to the government, it only affects the participants in the demonstrations and specifically excludes political leaders.

The Democratic Party criticized the proposal. Abhisit Vejjajiva said the law would free people who killed, burned property, and insulted the monarchy. Thaksin Shinawatra also allows him to return to Thailand. Human Rights Watch also rejected the law. It is an insult to the relatives of the victims and makes the army seem like an untouchable one. Both militant activists and soldiers who were responsible for deaths during the riots would get away with impunity. Worachai Hema contradicted this representation on August 2nd.

A group of victim representatives tried to propose an alternative version of the law that allows criminal proceedings against violent criminals and those responsible for property damage. Both Pheu Thai and the UDD rejected the proposal. In addition, the initiators could not find the 20 parliamentarians who would have been necessary to formally submit it to the House of Representatives.

On November 1, 2013, the House of Representatives adopted the Amnesty Act, shortly before the government extended the scope of the Amnesty Act. The adopted version was valid for offenses from 2004, whereby the offense of lese majesty was excluded from the penalty. According to the Democratic Party, it enabled Thaksin Shinawatra to return to Thailand. Parts of the “red shirts” also criticized this full amnesty for all sides, including those responsible for the killing of demonstrators. Even the original initiator of the amnesty law, Worachai Hema, no longer agreed with the heavily modified version of his draft and together with three other “red shirts” abstained from voting in parliament. A first mass demonstration against the law with thousands of participants took place the day before it was passed, on October 31. The Senate should discuss the proposal the following week.

Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra announced on November 7th that she would overturn the law in the face of violent protests. The Senate unanimously rejected the draft amnesty law on November 11th. The demonstrations continued regardless, and as a result the situation escalated into months of political crisis .

Sacrifice and cost

According to official figures, 88 people were killed and nearly 1,900 injured from the start of the demonstrations on March 12. Government information only records identified victims. In addition to demonstrators, the dead included police officers, soldiers, national and international media representatives (including Fabio Polenghi from Milan ) as well as rescue workers and uninvolved civilians. According to other sources, the riots left 91 dead and over 2,000 injured.

The government claimed the occupation cost 150 to 200 billion baht , which at the time was about 5 billion euros .

International reactions

UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon offered the UN to mediate several times. The Thai government rejected this mediation offer on the grounds that Thailand could solve its problems itself.

Amnesty International accused the Thai government of violating human rights . The organization indicated that the military fired live ammunition at the unarmed. Immediately after the occupation was disbanded, Human Rights Watch (HRW) criticized the arrest of the eight captured UDD leaders in unknown locations and called for an official charge or the immediate release of the prisoners. The organization criticized both the government and the UDD's behavior. Violence emanated from both sides. Various other human rights organizations criticized the one-sided investigation into the events. While many red shirts were prosecuted for terrorism, the public prosecutor did not charge a single representative of the security services.

literature

- James Buchanan: Translating Thailand's Protests. An Analysis of Red Shirt Rhetoric. In: ASEAS - Austrian Journal of South-East Asian Studies. Vol. 6, No. 1, 2013, pp. 60–80 (English; PDF; 10.37 kB). Retrieved September 5, 2013.

- Michael K. Connors: Thailand's Emergency State. Struggles and Transformations . In: Southeast Asian Affairs . tape 2011 . Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore 2011, ISBN 978-981-4345-03-3 , pp. 287–305 , JSTOR : 41418649 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- Tim Forsyth: Thailand's Red Shirt Protests. Popular Movement or Dangerous Street Theater? In: Social Movement Studies . tape 9 , no. 4 , 2010, p. 461-467 , doi : 10.1080 / 14742837.2010.522313 .

- Michael John Montesano, Pavin Chachavalpongpun, Aekapol Chongvilaivan (eds.): Bangkok May 2010. Perspectives on a Divided Thailand . Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore 2012, ISBN 978-981-4345-35-4 .

- Michael H. Nelson: Thailand's Legitimacy Conflict between the Red Shirt Protesters and the Abhisit Government. Aspects of a Complex Political Struggle . In: Security and Peace . tape 29 , no. 1 , 2011, p. 14-18 (English, online [accessed January 4, 2013]).

- Claudio Sopranzetti: Red Journeys. Inside the Thai Red-Shirt Movement . Silkworm Books, Chiang Mai 2012, ISBN 978-6-16215035-7 .

- Naruemon Thabchumpon, Duncan McCargo : Urbanized Villagers in the 2010 Thai Redshirt Protests. Not Just Poor Farmers? In: Asian Survey. Vol. 51, No. 6, November / December 2011, ISSN 0004-4687 , doi : 10.1525 / as.2011.51.6.993 , pp. 993-1018 (English; evaluation of interviews with 400 demonstrators and 57 organizers during the riots).

Web links

- Recommendations of the Truth for Reconciliation Commission of Thailand (TRCT) towards the policies ... (PDF 190 kB) In: Official website of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. September 2012, accessed on September 18, 2012 (English, unofficial translation of the policy recommendations).

- Alan Taylor: Protests turn deadly in Thailand. In: The Big Picture. May 17, 2010, accessed on January 14, 2012 (English, impressive pictures of the cast).

- Sandra Schulz and Thilo Thielke: What is Thailand's disease, Minister? In: Spiegel Online . July 15, 2010, accessed on January 14, 2012 (interview with Thai Foreign Minister Kasit Piromya on the unrest).

- Marko Martin: The silence after the shots. In: The world . August 24, 2010, accessed on January 14, 2012 (background report on the days after the riots).

- Xavier Monthéard: King, Citizen, Peasant. Pictures of the failed revolt in Thailand. In: Le Monde Diplomatique . July 9, 2010, accessed on January 14, 2012 (background report on the mood among UDD members in the aftermath of the unrest).

- Descent into chaos. Thailand's 2010 Red Shirt Protests and the Government Crackdown. (PDF) In: Human Rights Watch. May 3, 2011, accessed on July 2, 2012 (English, detailed report on the unrest).

Individual evidence

- ^ Emergency rule in Bangkok may be lifted by New Year . In: xinhuanet. November 16, 2010, accessed on November 26, 2010 (English): "The mandate for imposing the state of emergency is scheduled to expire on Jan. 4, he said."

- ↑ a b Thai government wants to lift the state of emergency from Wednesday. In: stern.de. December 21, 2010, archived from the original on October 19, 2013 ; accessed on December 21, 2010 : "After a corresponding decision by the cabinet, the regulation will be suspended from tomorrow ..."

- ↑ Charter approved with 57.81 per cent of votes: official results. In: The Nation . Archived from the original on August 4, 2016 ; retrieved on August 20, 2017 (English): "The Election Commission officially announced Monday that the draft constitution was approved by 14.727 million of voters of 57.81 per cent of voters"

- ↑ a b Background: This is how the conflict in Thailand escalated. In: Deutsche Welle . November 26, 2008, accessed on September 30, 2010 : "The political crisis in Thailand has its roots in 2001. Back then, the election victory of populist telecom billionaire Thaksin Shinawatra divided the country."

- ^ New head of government has been elected - protests again. In: The world. December 15, 2008, accessed on September 30, 2010 : “Abhisit Vejjajiva is the new Prime Minister of Thailand. The 44-year-old is the youngest head of government the country has ever had. "

- ^ State of emergency in Pattaya. In: Tagesschau . April 11, 2009, archived from the original on April 14, 2009 ; Retrieved January 8, 2013 .

- ↑ Two dead in protests in Bangkok. In: Tagesschau. April 13, 2009, archived from the original on April 16, 2009 ; Retrieved January 8, 2013 .

- ↑ Violent unrest - tourists leave Thailand. In: The world. April 13, 2009, accessed on September 30, 2010 : "The power struggle between the government and the opposition in Bangkok has degenerated into street battles."

- ↑ Somchai Jitsuchon and Kaspar Richter: Thailand's Poverty Maps. (pdf; 3.9 MB) From Construction to Application. In: World Bank - Official website. Retrieved July 18, 2011 .

- ^ A b c d Jan Andrejkovits: Regional imbalance in Thailand . The split in Thai society. 1st edition. Publishing house for academic texts, 2009, ISBN 978-3-640-29014-7 , pp. 12 .

- ↑ Oliver Meiler: Bhumibol is "a little sick". In: Süddeutsche . December 4, 2008, archived from the original on February 16, 2009 ; Retrieved September 30, 2010 (original website no longer available): "Instead of making a seminal speech, Thailand's King Bhumibol is silent"

- ^ Street battle in Thailand Fiery surrender. In: Frankfurter Rundschau . May 19, 2010, archived from the original on May 22, 2010 ; Retrieved January 8, 2013 (original website no longer available).

- ^ Urbanized Villagers in the 2010 Thai Redshirt Protests . In: Asian Survey Vol. 51, No. 6 (November / December 2011) . S. 1003 .

- ↑ a b c Urbanized Villagers in the 2010 Thai Redshirt Protests . In: Asian Survey Vol. 51, No. 6 (November / December 2011) . S. 999 ff .

- ↑ Petchanet: Thailand raises minimum dare. In: ThailandBusinessNews. December 10, 2010, archived from the original on September 23, 2012 ; accessed on March 25, 2013 .

- ↑ a b c d e f Urbanized Villagers in the 2010 Thai Redshirt Protests . In: Asian Survey Vol. 51, No. 6 (November / December 2011) . S. 995 ff .

- ↑ a b c Urbanized Villagers in the 2010 Thai Redshirt Protests . In: Asian Survey Vol. 51, No. 6 (November / December 2011) . S. 1009 ff .

- ^ A b Urbanized Villagers in the 2010 Thai Redshirt Protests . In: Asian Survey Vol. 51, No. 6 (November / December 2011) . S. 1015 ff .

- ↑ Descent into Chaos. In: Human Rights Watch. May 3, 2011, pp. 44ff , accessed on September 18, 2012 .

- ↑ New protest with an extreme disgust factor: demonstrators spill their own blood. In: News . March 17, 2010, accessed on September 30, 2010 : "There they poured out bottles of blood that they had collected from among their fellow demonstrators."

- ↑ The "Red Shirts" invade Bangkok city center, April 3, 2010 (I). In: newlifebangkok. Retrieved October 19, 2013 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Thailand. (PDF; 27 kB) country summary. In: Human Rights Watch. January 2011, accessed on March 28, 2012 (English, summary of the human rights situation in Thailand 2010. A large part of the report deals with the unrest): "Political instability and polarization continued in 2010, and occasionally resulted in violence."

- ^ Abhisit Vejjajiva: The Prime Minister's Special Directive No. 1/2553. (PDF) The Establishment of the Center for the Resolution of the Emergency Situation. In: Official website of the Thai Foreign Ministry. April 7, 2010, archived from the original on May 21, 2012 ; Retrieved on March 27, 2012 (English, unofficial translation of the founding directive of the CRES): "With a view to facilitating the appropriate and effective resolution of the severe emergency situation ..., the Council of the Ministers hereby resolves to establish the Center for the Resolution of the Emergency Situation (CRES), of which the composition and mandate are as follows ... "

- ↑ Alexander Mitschik: Red shirts storm television station. In: The press . April 9, 2010, accessed on September 30, 2010 : "The opposition celebrates a stage victory against Prime Minister Abhisit."

- ↑ Robin Henry: Nine dead as Thai troops clash with Red Shirt protesters. In: The Sunday Times . April 10, 2010, accessed on September 30, 2010 (English): "A series of street battles broke when troops tried to seize back control of the parts of capital being occupied by Red Shirt protesters."

- ↑ Descent into Chaos. In: Human Rights Watch. May 3, 2011, p. 58 , accessed September 18, 2012 .

- ↑ Red shirts embarrass the police in Bangkok. In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung . April 16, 2010, accessed September 30, 2010 (Thai opposition leaders escape police presence).

- ^ Restructuring the Center for the Resolution of the Emergency Situation to Streamline Efforts to Enforce Law and Order. In: Thai Ministry of Public Relations. April 17, 2010, archived from the original on July 12, 2011 ; Retrieved on March 27, 2012 : “In this connection, Prime Minister Abhisit Vejjajiva has appointed General Anupong Paochinda, Commander-in-Chief of the Royal Thai Army, as Chief Official in charge of operations, replacing Deputy Prime Minister Suthep Thaugsuban ... referring to the failed attempt by the police on April 16 to arrest those protest leaders. "

- ^ Sophie Mühlmann: Peaceful Agreement in Thailand. In: The world. May 5, 2010, accessed on September 30, 2010 : "After weeks of protests, government and opposition approve early elections"

- ↑ Strangers attack the election commission in Thailand. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . May 10, 2010, accessed on September 30, 2010 : "No one was injured in the most recent incidents on Sunday evening, said a police spokesman on Monday."

- ↑ The end of the protests is not in sight. In: The Farang. May 10, 2010, archived from the original on July 19, 2013 ; Retrieved on December 18, 2018 (original website no longer available): "Yesterday a leader of the" red shirts "announced that they would not start their way home until the Deputy Prime Minister Suthep Thaugsuban was questioned by the police and an investigation was initiated."

- ^ End of the opposition protests in sight. In: The Standard . May 10, 2010, accessed on September 30, 2010 : "Demonstrators set new conditions for withdrawal: Deputy head of government should be held accountable"

- ↑ One dead, Red Shirts military chief seriously injured. In: Spiegel Online. May 13, 2010, accessed on September 30, 2010 : "A prominent leader of the anti-government protests was seriously injured in the head by gunfire."

- ↑ a b c d e civil war scenes in Bangkok. In: Stern . May 16, 2010, accessed on September 30, 2010 : "Over the weekend, government opponents in Bangkok resisted the army's access using guerrilla methods."

- ^ A b c Sophie Mühlmann: Waiting for the last fight. In: The world. May 18, 2010, accessed on September 30, 2010 : "Bit by bit the troops in Bangkok advance against the entrenched red shirts - Hope for the King"

- ^ The Center for Resolution of Emergency Situation declared that 106 bank accounts have been frozen. In: Pattaya Times. May 15, 2010; Archived from the original on November 27, 2010 ; Retrieved on March 27, 2012 (English): "The Center for Resolution of Emergency Situation declared that 106 bank accounts have been frozen as a measure to cut support for red-shirt protesters."

- ↑ https://www.deutschlandfunk.de/fuer-bangkok-gilt-eine-reisewarnung.694.de.html?dram:article_id=68546

- ↑ Protest camp is disbanded. In: ORF . Accessed on September 30, 2010 : "The occupation of the center of Bangkok is over, announced the opposition leaders."

- ↑ The "City of Angels" is on fire. In: Frankfurter Rundschau. Retrieved May 20, 2010 .

- ↑ Teesha: List of the buildings that the red shirts set on fire . In: Pratu Namo. May 20, 2010, accessed September 30, 2010 .

- ↑ Ten bodies found in the ruined fire. (No longer available online.) In: ORF. Formerly in the original ; Retrieved September 30, 2010 : "Ten bodies were found in the Central World shopping center that was set on fire in the Thai capital, Bangkok."

- ^ Billows of smoke over the city. In: ORF. Retrieved September 30, 2010 : “The stock exchange and shopping malls were set on fire. In other parts of the country too, buildings went up in flames. "

- ↑ a b Only identified dead count. In: Frankfurter Rundschau. May 20, 2010, archived from the original on May 26, 2010 ; Retrieved January 8, 2013 .

- ^ Richard Barrow: Cleaning Silom Road. In: My Thailand (iPhone) Blog. May 23, 2010, archived from the original on November 29, 2010 ; accessed on September 30, 2010 (English): "This morning, I caught the newly re-opened BTS Skytrain and MRT Subway to Silom to witness first-hand Bangkok people coming out to help clean up their community."

- ^ Richard Barrow: Clean-Up on Ratchadamri Road. In: My Thailand (iPhone) Blog. May 23, 2010, archived from the original on November 29, 2010 ; accessed on September 30, 2010 (English): "After walking around Silom and Saladaeng, taking pictures of Bangkok volunteers cleaning up their city, I then decided to walk up Ratchadamri Road towards Ratchaprasong."

- ↑ a b c d Legal steps against "red shirts". (No longer available online.) In: ORF. Formerly in the original ; accessed on September 30, 2010 : "After the anti-government demonstrations in Bangkok, Thailand's government is planning further legal steps against the" red shirts "and their mentor Thaksin Shinawatra."

- ↑ https://www.diepresse.com/574478/thailand-auslander-wegen-demo-teilnahme-angklagt

- ↑ a b Warrant for arrest against Thaksin for terrorism. (No longer available online.) In: ORF. Formerly in the original ; Retrieved September 30, 2010 : "A Bangkok court today issued an arrest warrant for former Thai Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra."

- ↑ a b Dead in the burned-out shopping center. In: Frankfurter Rundschau. May 21, 2010, archived from the original on May 26, 2010 ; Retrieved January 8, 2013 .

- ↑ Alternative Thailand: Evidence of terrorism ignored by international medias. In: vimeo. May 27, 2010, accessed on September 30, 2010 (English, video compilation).

- ^ Crisis in Thailand: Government extends state of emergency. In: spiegel.de. Retrieved June 7, 2010 .

- ^ Bomb explosion in Bangkok: Another state of emergency. In: ORF. July 30, 2010, accessed on September 30, 2010 : "A man was seriously injured in a bomb explosion in the Thai capital Bangkok this morning."

- ↑ Explosion in the center of Bangkok. In: ORF. August 27, 2010, accessed on September 30, 2010 : "A grenade exploded in front of a hotel and a shopping mall in the Thai capital Bangkok."

- ^ "Red" protests in Thailand. In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung. September 19, 2010, accessed on September 30, 2010 : "On Sunday several thousand demonstrators of the anti-government" red shirts "took to the streets in Bangkok."

- ↑ Nicola Glass: Red Sunday in Bangkok. In: the daily newspaper . September 20, 2010, accessed on September 30, 2010 : "Four years after the military coup and four months after the bloody crackdown on their protests, the red shirts are back on the streets."

- ↑ a b c Red protest on the streets of Bangkok. In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung. March 12, 2011, accessed on May 19, 2011 : "The so-called red shirts remembered the beginning of their demonstrations almost exactly a year ago, which the army violently ended with tanks and water cannons after weeks of protest."

- ↑ a b Tens of thousands of "red shirts" demonstrated in Bangkok. In: ORF. April 10, 2011, accessed on May 19, 2011 (Tens of thousands of supporters of the opposition “red shirts” took to the streets in the Thai capital Bangkok to commemorate the bloody clashes with the army a year ago.).

- ↑ a b c Nicola Glass: Nothing to feel of reconciliation. In: the daily newspaper. May 19, 2011, accessed on May 20, 2011 : “One year after the crackdown on their protests, the so-called red shirts are commemorating their dead. State investigations have so far been delayed. "

- ↑ a b Freddy Surachai: Mud Battle of the King Faithful. In: Spiegel Online. April 25, 2011, accessed on May 19, 2011 (At the same time, the Department of Special Investigation (DSI) initiated proceedings against ten leading red shirts for libel of majesty.).

- ↑ Thailand: Terrorist charges against Thaksin called for. In: ORF. July 29, 2010, accessed on September 30, 2010 : "Thailand's police have called for terrorism charges against the ousted ex-Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra and 24 other opposition figures."

- ^ Thailand: Oppositionists sued for terrorism. In: ORF. August 12, 2010, accessed on September 30, 2010 : "Several months after the crackdown on anti-government protests in Bangkok, 17 members of the Thai opposition movement have been charged with terrorism."

- ↑ 'Conspiracy' behind 'Seh Daeng death. In: Bangkok Post . June 23, 2011, accessed on November 8, 2011 (English): "Red-shirt core member Jatuporn Prompan was likely the person behind the killing of army specialist Khattiya Sawasdipol, ..., secretary-general Suthep Thaugsuban said."

- ^ Nicola Glass: State of emergency lifted again. In: the daily newspaper. December 21, 2010, accessed on December 27, 2010 : “Thailand's rulers are currently no longer counting on violent protests by the opposition“ red shirts ”. The role of the army in the murder of civilians remains unclear. "

- ↑ DSI cancels bail for 2 red leaders. In: Bangkok Post. April 19, 2011, accessed on October 8, 2012 (English): " Pol Lt-Col Thawal said summonses would be issued for 18 UDD leaders to report to the DSI to acknowledge read majeste charges between May 2 and May 4. "

- ↑ a b c d Marco Kauffmann Bossart: Sober view of the Bangkok unrest. In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung. September 18, 2012, accessed on September 18, 2012 : "Two and a half years after the bloody clashes between" red shirts "critical of the government and monarchist" yellow shirts "in Bangkok, the Truth for Reconciliation Commission of Thailand has published its final report."

- ↑ Former head of government charged with murder. In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung. December 13, 2012, accessed on December 14, 2012 : "Two and a half years after the bloody unrest in Thailand, former Prime Minister Abhisit Vejjajiva has been charged with murder."

- ^ DSI chief defends murder charge. In: Bangkok Post. December 13, 2012, accessed on December 14, 2012 (English): "Department of Special Investigation chief Tarit Pengdith on Friday defended the DSI's decision to lay murder charges"

- ↑ murder charges against ex-head of government. In: DerStandard.at , December 12, 2013.

- ↑ Abhisit reports for indictment. In: Bangkok Post , December 12, 2013.

- ↑ Thomas Fuller: Thai Court Dismisses Murder Case Against Ex-Leaders. In: The New York Times (online), August 28, 2014.

- ↑ Somroutai Sapsomboon: Worachai's amnesty bill just a trial balloon for govt. In: The Nation . August 2, 2013, accessed August 7, 2013 .

- ↑ a b c No Amnesty for Rights Abusers. Proposed Law Would Entrench Culture of Impunity. In: Human Rights Watch. August 5, 2013, accessed on August 7, 2013 (English): "The ruling party's amnesty bill lets both soldiers and militants responsible for deaths during the 2010 upheaval off the hook"

- ↑ a b c Old wounds. Amnesty Law in Thailand. In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung. August 7, 2013, accessed on August 7, 2013 : "In Thailand, a government-backed amnesty law is causing a stir."

- ↑ Massive police presence against protests. In: The Standard. August 7, 2013, accessed on August 7, 2013 : "An estimated 1,000 demonstrators wanted to protest against a planned amnesty law on Wednesday with the support of the parliamentary opposition."

- ↑ Thailand's red shirts feel betrayed. In: Asia One. November 2, 2013, archived from the original on November 6, 2013 ; Retrieved on November 7, 2013 (English): "Four Pheu Thai MPs - Nuttawut Saikuar , Weng Tojirakarn , Worachai Hema and Khattiya Sawasdipol - abstained from the vote."

- ^ Till Fähnders: Amnesty Act stirs up tension. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. November 1, 2013, accessed on November 6, 2013 : “The Thai House of Commons passed a controversial amnesty law on Friday ... the amnesty has been in place for all those involved in political protests since January 2004. The only exceptions are those who, according to Thai law, are Have made lese majesty a criminal offense. "

- ↑ Thailand overturns controversial amnesty law after protests. In: The Standard. November 7, 2013, accessed on November 7, 2013 : "After violent protests, the Thai Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra surprisingly overturned a planned amnesty law."

- ↑ Mongkol Bangprapa: Senators shoot down blanket amnesty bill. In: Bangkok Post. November 12, 2013, accessed on November 25, 2013 (English): "After 12 hours of debate, the senators shot down the controversial bill by 140 votes to 0."

- ↑ Marko Martin: The silence after the shots. In: The world. August 24, 2010, accessed on September 30, 2010 : "A few months after the riots, Bangkok is as calm as if nothing had ever happened"

- ↑ Nicola Glass: Forbearance with the ruling party. In: the daily newspaper. November 29, 2010, accessed on December 1, 2010 : "The spring violence left 91 dead and nearly 2,000 injured."

- ↑ Government in Bangkok rejects talks with insurgents. (No longer available online.) In: Der Westen. May 16, 2010, formerly in the original ; retrieved on September 30, 2010 : "A leader of the protest movement offered new talks under UN mediation, but the Thai government immediately refused."

- ^ Thai military must halt reckless use of lethal force. In: Amnesty International. May 18, 2010, accessed on September 30, 2010 (English): "Thai soldiers must immediately stop firing live ammunition into several large areas in Bangkok where anti-government protesters are gathered, Amnesty International said today."