Winterstein (Saxon Switzerland)

| Winterstein (rear robbery castle) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

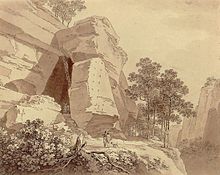

Winterstein from the east, on the left the Pechofenhorns, on the right in the background the Gleitmannshorns |

||

| height | 389 m above sea level HN | |

| location | Saxony | |

| Mountains | Elbe Sandstone Mountains | |

| Coordinates | 50 ° 54 '38 " N , 14 ° 16' 48" E | |

|

|

||

| Type | Rock massif | |

| rock | Sandstone | |

The Winterstein , also known as the Rear Robbery Castle or Raubstein , is a single, elongated rock massif in the Upper Saxon Switzerland in the Free State of Saxony . The medieval rock castle Winterstein was once located on the 389-meter-high summit, remains of which can still be seen, such as beam rebates, carved steps and the cistern . The castle, which was probably built in the 13th century, was first mentioned in 1379 as a Bohemian pledge. It passed into Saxon ownership in 1404, but it had already expired by 1450. The rock massif of the Winterstein is a popular destination for hikes, the summit plateau can be reached via stairs and ladders.

Location and geology

The freestanding and its surroundings by about 90 to 100 meters, about 120 × 50 meters large Winterstein is located in the almost unpopulated and densely forested Upper Saxon Switzerland above the Großer Zschand in the district of Ostrau . The rock is about 150 meters in front of the approximately 30 meters higher Bärfang walls south of the Winterstein as a remaining hard sandstone . It is located within the Saxon Switzerland National Park , just outside the core zone of the eastern national park area. A few kilometers to the east is the Great Zschand the armory . The Kleine Zschand stretches west of the Winterstein , towered over by the Großer and Kleiner Winterberg . The Wintersteinwächter climbing summit , located in the south and separated only by a narrow chasm, belongs to the rock complex of the Winterstein .

Like the entire Elbe Sandstone Mountains , the winter stone was created from deposits of a Cretaceous sea, which deposited clastic sediments up to 400 meters thick in the Turonium and Coniacium . Like the neighboring Bärfang walls, the Winterstein belongs to the two horizons of the sandstone levels c3 and d of the Elbe Sandstone Mountains according to the original petrographic-morphological classification by Friedrich Lamprecht . While the horizon c3 still belongs to the so-called Postelwitz formation and is more of a slope-forming structure, the wall-forming horizon d forms the thickest part of the Schrammstein formation at 50 to 80 meters. On the Winterstein, the vertical rock faces from both horizons reach a height of up to 40 meters, through the slope-forming horizon c3 below , the entire rock rises a good 100 meters above the forest areas north of it. Between the two horizons, the so-called lower cave horizon on the Winterstein, which is clearly visible in the form of rock terraces and overhangs in many places of the Elbe Sandstone Mountains, forms a sometimes several meters wide rock terrace on the south and east side of the rock. On the north and west side, this separating layer is only recognizable as a thin, inaccessible band. The lower horizon c3 is delimited as a narrow rock band around the entire winter stone from the layers following in the hanging wall.

Access to the Winterstein

The Winterstein can be easily reached on foot from various directions. From the Kirnitzschtal up through the Kleiner Zschand, a hiking trail leads past the foot of the rock massif, which can also be reached via the lower Affenstein promenade . Another starting point for a visit to the Winterstein is the Neumannmühle in the Kirnitzschtal. From there the path leads through the Großer Zschand and then steeply through the Raubsteinschluchten up to the notch between the Bärfangwände and the Winterstein. From Schmilka the path runs over the Großer Winterberg to the Winterstein.

A branch leads from the notch over stairs and ladders to the wide rock terrace on the south side of the rock massif to the large cleft cave at the dividing layer of the sandstone steps . From there, sure-footed hikers who do not suffer from vertigo can reach the summit plateau of the Winterstein via a free-standing, around ten meter high ladder in the cave and narrow crevices with steps. At the base of the Winterstein can be circled on narrow ledges of rock, there are various rock caves and overhangs that can be used by mountaineers as a boofen for overnight stays.

history

The castle complex on the Winterstein is considered to be the largest and oldest of its kind in the Upper Saxon Switzerland. However, there are only a few written sources on their formation and history. Both are therefore repeatedly the subject of historical controversy.

Creation of the castle

The castle, like other rock castles in the Elbe Sandstone Mountains, was probably built by the Bohemian aristocratic family of the Berken von der Duba in the course of expanding their rule in the 13th century, in the middle of which the earliest ceramic finds date. The assumption that the Berken protected a trade route through their area from Schandau or Postelwitz to Zittau with the castle is contested in recent literature, the existence of this road is even questioned. Instead of the Berken, the Bohemian aristocratic family of the Markwartitze come into question as builders due to comparisons with the Neurathen Castle . Another theory is that the Winterstein, like other rock castles in the then Bohemian border region of Saxon Switzerland, was used for the systematic expansion of fortifications in the course of the Mongol storm and the retreat of the Bohemian King Wenceslaus I after the defeat of the Silesian Duke Henry II in the Battle of Liegnitz in 1241 belonged to. As a direct consequence of the Mongol storm in the area of today's Saxon Switzerland there is only the Upper Lusatian border document from 1241 between the king and the bishop of Meissen as a source, in which the Winterstein is not mentioned.

The Winterstein was first mentioned in a document in 1379, when the Bohemian King Wenceslaus IV pledged it to his chamberlain, Thimo von Colditz , owner of the Graupen estate , as an accessory to the Pirna castle district, but as an independent pledge . The Winterstein is the earliest mentioned rock castle in the Upper Saxon Switzerland. The pledge was confirmed in 1381, and Wenceslaus IV redeemed it in 1391. Still belonging to Pirna, the Winterstein was pledged again in 1396 to King Wenzel's chamberlain Burkhard Strnad von Janowitz . In 1397 the king asked the residents of the pledged areas to pay taxes to Strnad. From this it follows that the Winterstein belonged to villages that brought in income. There is a lack of more precise written information about the communities involved; we can assume that surrounding towns and villages such as Bad Schandau , Altendorf and Lichtenhain , possibly Saupsdorf and Hinterhermsdorf .

Unclear ownership of the castle

There are sometimes only guesses about further changes of ownership. Burkhard Strnad von Janowitz was murdered as early as 1397 on behalf of Duke Johann II von Troppau-Ratibor . According to this, Johann von Wartenberg , Lord von Blankenstein near Tetschen , seems to have been the owner of the pledge. The Winterstein went to the Meissnian Margrave Wilhelm I in 1404 together with the Care Pirna, which had been part of the Bohemian Crown up to that point . This change of ownership is related to the Dohna feud , in which the Margrave sought to own the entire area of today's Saxon Switzerland bring. In the margravial account books and the Dresden treasury bills it is noted that between 1406 and 1408 there was a margrave-Meissnian garrison under captain von Techerwitz on the Winterstein. However, no income was given, only expenses.

The further possession of the winter stone is uncertain. Georg Pilk and most of the researchers with him assume that the Winterstein returned to Bohemian ownership around 1440. In the sources from 1441 a "Recke zcum Wintersteine" is mentioned, who participated in the "Wartenberg feud" on the part of the Wartenbergers. In the same year, Elector Friedrich the Meek asked of the Berken von der Duba as lords of the Lordship of Wildenstein and Hohnstein as well as of Johann von Wartenberg auf Blankenstein, the Recken and other named Bohemian castle knights to give no more support, but rather to give him, the elector, and to help the Bishop of Meissen fight them. Due to the commitment of the Berken and the Wartenbergers, the warrior von Winterstein seems to have his castle removed that same year. It then came into the possession of Johann von Wartenberg, who sold it on July 24, 1441 to the “Land and Cities ” of Upper Lusatia.

The assignment of the Recken von Winterstein and the subsequent sale of his castle to the Upper Lusatians to the rock castle on today's Winterstein in Saxon Switzerland is controversial, especially since the existence of a trade route - an essential prerequisite for robber baronism - near the Winterstein is also doubted . A trade route from the documented disembarkation point in Postelwitz past the foot of Falkenstein and Affensteinen and then north past Winterstein to Großer Zschand and on to Sebnitz is not documented and is only named in works by local historians of the 19th century. As early as 1950, later researchers had greater doubts about the existence of the road. The importance of the Postelwitzer Umschlagplatz was, as far as it was documented, only of secondary importance compared to the Schandauer Elbhafen. The "Reitsteig" leading from Sebnitz over the Großer Zschand and south of the Großer Winterberg to the Elbe at Herrnskretschen can only be traced back to around 1450, i.e. after the winter stone was no longer used.

As early as the 19th century, individual researchers suspected that the castle of the Recken von Winterstein was a Winterstein castle in the vicinity of Lückendorf in the Zittau Mountains , which was acquired together with Neuhaus Castle, which was named Karlsfried centuries later . Possibly it formed a double castle together with Neuhaus, for which, however, no archaeological findings are available. The deed of purchase was probably burned in Zittau in 1757. There is only one entry in the Görlitz council bills and in the Guben yearbooks, as well as a registration with Carpzov. According to the entries in Görlitz and Löbau's accounts, demolition work only took place at the Neuhaus. There is no written record of the demolition of the Winterstein. Even the name of the robber baron leads to the assumption that a different castle is meant. "Recke" is a Germanized spelling of the Czech name "Racek", so the Recke zum Winterstein is documented as "Racek von or zum Wintersteine". For a Bohemian knight and probable vassal of Johann von Wartenberg, the possession of a castle in Saxony since 1406, whose earlier income was no longer available to him, was hardly possible. On the other hand, "Racek" is only mentioned in the peace negotiations of the Wettins - the Wartenberger explicitly doubts that he would be able to persuade his followers to make peace with them - while he does not appear in the Upper Lusatian sources. Georg Pilk, and most of the authors with him, assumed that the Winterstein was torn down after it was bought in 1442 by the Association of Towns; he judged the earlier assignment to a castle in the Zittau Mountains that was not precisely located. The more recent research casts this assignment into doubt and localized the castle of the Recken von Winterstein with greater probability in the Zittau Mountains.

Decay after 1400

According to the newer hypothesis, after the margravial garrison withdrew, the Winterstein was no longer used permanently and fell into disrepair. The Berken von der Duba took possession of the area around the Winterstein, which was not far from their center of power on the Neuer Wildenstein , but they no longer used the castle. With the sale of the Wildenstein estate by the Berken, the formerly built-up Winterstein finally came to Saxony in 1451 and became part of the Hohnstein district in 1452 . As early as 1456, in the so-called castle directory, the Winterstein was only one of those castles that “were built before geczyten” ( quoted from Müller / Weinhold, 2010, p. 8. ).

In the map created by Matthias Oeder for the recording of the state of the Electorate of Saxony from 1592, the Winterstein is mentioned again, after which the name is no longer documented in writing in the historical sources for more than 300 years. In memory of the robber barons who allegedly lived there, the population only referred to the rock as "rear" or "large robbery castle". The name was still unknown to Wilhelm Leberecht Götzinger , he called the rock in 1804 in his main work Schandau and its surroundings or description of the so-called Saxon Switzerland , with which he presented a first comprehensive description of Saxon Switzerland, as Raubstein . Various researchers suspected a winter stone in the area of the Upper Saxon Switzerland since the beginning of the 19th century based on the castle directory, but in addition to the rear robbery castle, the New Wildenstein and the Lorenz stones about one kilometer north of the Winterstein were also assumed to be the location. It was not until the publication of the Oederschen Karte in 1889 that the name came into use again and could clearly be assigned to the rear robbery castle.

Tourist and climbing development since 1800

At the end of the 18th century there was already a climbing facility on the Winterstein. Adrian Zingg depicted it on a copper engraving from around 1790 of the Winter Stone, which he still referred to as "Raubstein". The date of its construction is unknown, it was first mentioned in writing by Götzinger in 1804. A first repair is documented for 1812. Hermann Krone took the oldest photographs of the Winterstein as early as 1855. Krone also took photos of the Winterstein in later years, a photo from around 1885 shows, among other things, the wooden ladder in the cleft cave. During his photo tours, Krone used the rear part of the cleft cave and the cellar of the residential tower on the upper castle as a darkroom .

After the Second World War, the stairs were dilapidated. Instead of being renovated, it was demolished on May 23, 1948 by members of the Wanderlust climbing club in 1896, on the grounds that there was a risk of accidents and the disfigurement of rocks. Due to the lack of an ascent opportunity for hikers and walkers, the winter stone corresponded to the definition of the climbing summit in the Saxon Switzerland climbing area and could be used as a climbing rock . Since members of the club subsequently carried out numerous first ascents on the Winterstein, it is assumed that they had previously "helped" with the deterioration of the stairs. At that time there were a total of 19 climbing routes and a few variants on Winterstein .

In 1952 the Naturfreunde Bad Schandau built a new staircase in the old place, which ended the short time of the Winterstein climbing summit. Since then, the summit plateau has been accessible again for hikers with a head for heights. Only the upstream climbing summit Wintersteinwächter (first ascent in 1921) is still used for climbing, as it is no longer accessible on foot from the summit plateau - unlike at the time of the Felsenburg. At the end of the 1990s, the climbing system was renewed and renovated.

The castle complex

As with the other rock castles in the area, the buildings of the Winterstein consisted largely of wood and half-timbering . As a result, there are only a few structural remains left, mainly beam rebates and anchors for planks and wooden struts as well as remains of the foundation. The castle consisted on the one hand of the lower and the upper castle directly on and on the rock, and on the other hand of upstream buildings through which the access was monitored. From the lower castle, which is located on the broad rock band formed by the narrow layer of the "lower cave horizon" between the sandstone layers c3 and d on the south side, about a third of the total height of the rock, was over the large cleft cave and ladders attached to reach the upper castle on the summit plateau. Based on the traces, especially in the lower castle, at least two different construction phases can be clearly distinguished. However, due to the lack of more precise traces and written records, these cannot be dated any further. Compared to other rock castles, the Winterstein was expanded relatively elaborately, probably by Thimo von Colditz, who, as royal chamberlain and governor of Wroclaw, was one of the most important men at the court of Wenceslaus IV.

Various excavations were made on the castle plateau, in the cleft cave and especially on the sandy southern slope. In the local history museum of Bad Schandau , various finds such as tile remains and pottery shards, iron nails, spurs and arrowheads as well as a short blade are kept. Hermann Krone made the first discoveries in the context of his photographic work; broken pieces and ceramic remains are still occasionally discovered.

Access and lower castle with cleft cave

Today's approach to Winterstein at an angle in the southwest corner of the rock corresponds to the earlier castle access from the second construction phase. At the entrance to today's first steel ladder, the beam bearings of a wooden gate can be recognized by a narrow and therefore easy to defend rock crevice. The subsequent steps in the sandstone , laid out in a slipway under a sloping rock as a kind of spiral stone , also come from the builders of the castle. You can use it to reach a second gate, also identifiable by means of folds, and the rock terrace at the beginning of the lower castle directly at the foot of the walls of the Winterstein. Various joists and niches carved out of the rock are still visible in this area from the buildings of the lower castle. Due to the folds reaching up to a height of seven meters, it can be assumed that the farm buildings there were two-story. The roofed battlement began to the right of the buildings and stretched over more than 100 meters along the entire terrace on the south side. In the ground and in the rock wall there are still traces of joist bearings and folds to accommodate the rafters. Above all, one can clearly see a post that is carved into the south wall, about a man-high and 90 centimeters deep. At the bend from the south wall to the east wall, bearings from a former watchtower are preserved on the outermost rock plateau. The battlements continued along the east wall formed by the “Wintersteinwächter” and ended at the north-east corner in a small post that was accessible via sandstone steps. On the north and west side of the rock, the terrace merges into the narrow, inaccessible separating layer between the sandstone horizons, where no additional weir systems were necessary. In the cut of the east wall there were further installations above the battlements on the rock terrace and a slightly recessed higher plateau. Presumably there was a defense platform there to protect the east side, which is more easily accessible for attackers.

In the first phase of construction of the castle, the access to the Winterstein was about 70 meters further to the east than today, about in the middle of the battlement, which was only built in the second phase. There you can see the carved rock steps through which the terrace of the battlement can be reached. The actual area of the lower castle only began at the level of the post in the south wall, the bar folds still present there suggest a corresponding barrier. The area of today's access was later included in the lower castle.

A series of palisades , shelters and narrow buildings adjoined the battlements in the northeast corner of the Winterstein . Since there was a seven-meter-wide, steep slope between the base rocks that provided access, this area of the castle was particularly secured. This area was also only built in the second construction phase.

The 15 meter deep and almost five meter wide cleft cave formed the center of the lower castle and was partly artificially expanded. The cave can be reached from the rock terrace of the battlements via a narrow gap with 24 sandstone steps. Bar rebates show that this approach was probably built over and secured with a further wooden gate at the beginning and at the end of the steps. Use as a horse stable, as Götzinger suspected in 1804, can probably be rejected in view of the approach that is hardly accessible for horses. The cleft cave - visible from the rows of folds in the wall and ceiling - was divided into three parts. The front part was covered by a wooden defensive platform, recognizable by its beam bearings, which served to defend the castle gate and courtyard of the lower castle. In the middle part, rows of benches were knocked out of the rock, which suggests it was used for living and sleeping purposes; Based on the folds in the walls, a multi-storey construction can also be assumed there, via which the ascent to the upper castle also took place. At the far end of the cave there is a cistern cut out of the rock, probably separated in the middle by boards or a stone wall , which was fed by wooden supply lines from above and along the cave walls. The folds for these supply lines can be seen from the ladder leading to the upper castle.

Oberburg

The only access to the upper castle that could be reached from the end of the ladder through rising rock chimneys with sandstone steps was via wooden ladders in place of today's steel ladder and the wooden platforms that were pulled in at the time. Some of these steps are still part of the entrance today, and some of them are covered by later built-ins.

The summit plateau was used for various residential and defense structures. On a slightly raised rock plinth in the eastern part of the plateau, a building foundation made of sandstone blocks with a base area of around 6.1 × 7.4 meters and walls up to 1.1 meters thick has been preserved. It is one of the very few buildings in the rock castles of Saxon Switzerland that can still be proven by the remains of the wall. There are different assumptions about the use and structural design. Originally only a guardroom was suspected there. The theory that prevailed was that it was the central residential tower used by the lord of the castle . It is not clear whether the other floors were built from stone or half-timbered above the sandstone basement. The basement of the tower, which is still preserved and accessible today, was carved into the rock base. It most likely did not serve as a dungeon , as previously assumed . A real dungeon put the tower does not appear to constitute, as no permanent closure of the upper floors was possible over the rock-hewn access to the basement and its opening to the basement. An originally suspected subsequent installation of the basement access is unlikely in view of the fact that the basement is slightly offset from the tower on the rock plinth and oriented towards the outer wall.

There were other buildings to the east of the tower, as well as on the Wintersteinwächter. For this purpose, planks bridged the gaps between the Winterstein and the Wintersteinwächter. On the base of the residential tower and on the Wintersteinwächter you can also see grooves that have been knocked out, with which rainwater was collected and barrels and the cistern in the cleft cave were fed. The locations of the barrels can still be seen from the niches and holes carved out of the rock on the base and on the winter stone guard. In front of the barrel niche in the rock plinth of the residential tower, a crossbow carved into the rock can also be seen on the floor . There was also a watchtower on the Wintersteinwächter, which stood on its easternmost rock head.

Another control room and various buildings had been erected at the western end of the rock massif. Their use is not clearly known. Due to the great distance to the residential tower and the isolated location, it is sometimes assumed that the castle dungeon was located here. This is also supported by some of the bar folds still present there, which probably blocked off the rock ledges located there, somewhat below the summit plateau, from the actual plateau. In addition, there was a post with a beacon and line of sight to the upstream castle guard on the Wartburg . Up until a few years ago, a chiseled board game could be seen in the floor of a watchtower that was detectable by means of post holes . Unfortunately, strangers destroyed the playing field between 2000 and 2001 with their own scratches.

Various freight elevators were used to supply the castle, both to the lower castle and to the upper castle. The abutments and joists carved out of the rock have been preserved on the summit plateau. The purpose of an A-shaped floor structure made of longitudinal and stamp folds on the north side of the upper castle , which was only discovered by aerophotogrammetry , is unclear . One assumption is that this is another crane foundation that was used, among other things, to supply timber. Another possibility can be the location of a blide .

Keep watch and watchtower

The castle complex also included a keeper on the present-day climbing summit Wartburg, about 200 meters west of the Winterstein, about 15 meters high . Steps and joists hewn into the sandstone are also visible on this rock. Essentially, the castle observatory consisted of a half-timbered building on the eastern plateau of the Wartburg, the rebates of which are still clearly visible on the summit. A narrow staircase carved out of a rock ridge on the north side served as access. A freight elevator next to the building was used for supplies.

About 400 meters northwest of the Winterstein down into the valley in the direction of Kleiner Zschand is the so-called “Bear Catch”, which also belonged to the rock castle. It is about two meters deep, rectangular and over 35 square meters in size, carved out of the sandstone or a basin. Chiseled steps lead from the pit to the location of a wooden watchtower, recognizable by the post holes that are still there. Contrary to the popular name, bear trapping was never used to catch bears, but was presumably a guard and control post at the entrance to the castle as well as on the old street leading into the Großer Zschand, roughly along today's Zeughausstraße. It is also assumed that it functions as a water reservoir, which is supported by the slope of the floor and an incision in the border that can be interpreted as an overflow. The actual function of this pit is, however, uncertain.

literature

- Hermann Lemme, Gerhard Engelmann: Between Sebnitz, Hinterhermsdorf and the Zschirnsteinen (= values of the German homeland . Volume 2). 3. Edition. Akademie Verlag, Berlin 1966, pp. 130-131.

- Christian Maaz: Winterstein - a critical analysis of historical sources. In: Castle research from Saxony. Issue 20 (2007), Deutsche Burgenvereinigung e. V., Landesgruppe Sachsen, pp. 57–72, ISBN 978-3-937517-75-9 .

- Matthias Mau: The rock castle Winterstein. Stiegenbuchverlag Mothes, Halle (Saale) 2008, DNB 990643867 .

- Anne Müller, Matthias Weinhold: The rock castle Winterstein. Reconstruction attempt based on the site findings. In: Castle research from Saxony. Issue 13 (2000), Deutsche Burgenvereinigung e. V., Landesgruppe Sachsen, pp. 16–39, ISBN 3-930036-46-0 .

- Anne Müller, Matthias Weinhold: Rock castles of Saxon Switzerland. Neurathen - Winterstein - Arnstein. Burgen, Schlösser und Wehrbauten series in Central Europe, Volume 23, Verlag Schnell and Steiner, Regensburg 2010, pp. 28–36, ISBN 978-3-7954-2303-2 .

- Alfred Neugebauer : The rock castle of the Recken vom Winterstein. In: Peter Rölke (Ed.): Hiking & Nature Guide Saxon Switzerland. Volume 1, Rölke, Dresden 1999, ISBN 3-934514-08-1 , pp. 127-129.

- Alfred Neugebauer: The rock castles of Saxon and Bohemian Switzerland. In: Castle research from Saxony. Issue 1 (1999), Deutsche Burgenvereinigung e. V., Landesgruppe Sachsen, pp. 9-17, ISBN 3-928492-42-X .

Web links

- The Winterstein on historisches-sachsen.net

- Weir systems in Saxon Switzerland, text sketch by local researcher Erich Pilz

- Photos from the Winterstein

- Saxon Switzerland National Park: route map with permitted approaches to Winterstein

- History of the winter stone as a climbing peak

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d Alfred Neugebauer: The rock castle of the Recken vom Winterstein. In: Peter Rölke (Ed.): Hiking & Nature Guide Saxon Switzerland. Volume 1, Verlag Rölke, Dresden 1999, ISBN 3-934514-08-1 , p. 127.

- ↑ a b c d e f Gerhard Engelmann, Hermann Lemme: Between Sebnitz, Hinterhermsdorf and the Zschirnsteinen (= values of the German homeland . Volume 2). 2nd Edition. Akademie Verlag, Berlin 1966, pp. 130-131.

- ^ Lithostratigraphic units of Germany. Postelwitz formation. In: Lithostratigrafisches Lexikon Deutschlands. April 17, 2008 ( Memento of the original from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (accessed December 10, 2013).

- ^ Lithostratigraphic units of Germany. Schrammstein formation. In: Lithostratigrafisches Lexikon Deutschlands. April 17, 2008 ( Memento of the original from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (accessed November 20, 2013).

- ↑ GEO montan, Society for Applied Geology mbH Freiberg (edit.): Analysis of potential for inclusion of parts of Saxon-Bohemian Switzerland as a UNESCO World Heritage Site; Part geology / geomorphology (investigation into the extraordinary universal value and integrity in the sense of the UNESCO World Heritage Convention) final report. On behalf of the Association of Friends of the Saxon Switzerland National Park, funded by Deutsche Umwelthilfe, Freiberg 2006, p. 24 ( Memento of the original dated December 2, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (accessed on November 20, 2013; PDF; 6.7 MB).

- ↑ Announcement of the Saxon State Ministry for Environment and Agriculture on the maintenance and development plan for the Saxon Switzerland National Park / part of mountain sports conception, section free overnight stay, Ref .: 63-8842.28, dated August 12, 2002 ( Memento des original dated December 2, 2013 on the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (accessed on November 6, 2011; PDF; 19 kB).

- ↑ a b Christian Maaz: Winterstein - a critical analysis of historical sources. In: Castle research from Saxony. Issue 20 (2007), Deutsche Burgenvereinigung e. V., Landesgruppe Sachsen, pp. 57–72.

- ↑ a b Christian Maaz: Winterstein - a critical analysis of historical sources. In: Castle research from Saxony. Issue 20 (2007), Deutsche Burgenvereinigung e. V., Landesgruppe Sachsen, p. 60 ff.

- ↑ Erich Pilz: About the development of the weir systems in Saxon Switzerland. Sebnitz 1964–1988 ( Memento of the original from April 12, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (accessed June 13, 2011).

- ^ Alfred Meiche: German history in the mirror of Saxon Switzerland. In: The mountaineer . Booklet 3, Verlag E. Beutelspacher & Co., Dresden 1924, p. 22.

- ↑ Alfred Meiche: Historical-topographical description of the Pirna administration. Dresden 1927, Königstein, p. 134 (accessed on October 2, 2011; PDF; 32.1 MB).

- ↑ a b Christian Maaz: Winterstein - a critical analysis of historical sources. In: Castle research from Saxony. Issue 20 (2007), Deutsche Burgenvereinigung e. V., Landesgruppe Sachsen, p. 58.

- ↑ Alfred Meiche: Historical-topographical description of the Pirna administration. Dresden 1927, Winterstein, p. 380 (accessed on October 2, 2011; PDF; 32.1 MB).

- ^ Hermann Lemme, Gerhard Engelmann: Between Sebnitz, Hinterhermsdorf and the Zschirnsteinen (= values of the German homeland . Volume 2). 3. Edition. Akademie Verlag, Berlin 1966, pp. 130 ff.

- ↑ a b c Alfred Meiche: Historical-topographical description of the Pirna administration. Dresden 1927, Winterstein, p. 381 (accessed on October 2, 2011; PDF; 32.1 MB).

- ↑ Christian Maaz: Winterstein - a critical analysis of historical sources. In: Castle research from Saxony. Issue 20 (2007), Deutsche Burgenvereinigung e. V., Landesgruppe Sachsen, p. 61.

- ↑ Christian Maaz: Winterstein - a critical analysis of historical sources. In: Castle research from Saxony. Issue 20 (2007), Deutsche Burgenvereinigung e. V., Landesgruppe Sachsen, p. 63.

- ↑ a b Richard Klos and Miloslav Sovadina: A mysterious castle in the Lusatian mountains. In: Oberlausitzer Heimatblätter . Issue 5, 2005.

- ↑ Codex Diplomaticus Lusatiae Superioris vol. IV, 1st part, p. 157, lines 18 ff., P. 172, lines 29 ff. And 195. Scriptores Rerum Lusaticarum , vol. 1, p. 71, lines 22 ff. Johann Benedict Carpzov III. , Analecta fastorum Zittaviensium, or historical scene of the praiseworthy old six-town of the Marggraffthum Ober-Lausitz Zittau , Zittau 1716, p. 155.

- ↑ Christian Maaz: Winterstein - a critical analysis of historical sources. In: Castle research from Saxony. Issue 20 (2007), Deutsche Burgenvereinigung e. V., Landesgruppe Sachsen, p. 68.

- ↑ a b Christian Maaz: Winterstein - a critical analysis of historical sources. In: Castle research from Saxony. Issue 20 (2007), Deutsche Burgenvereinigung e. V., Landesgruppe Sachsen, p. 69.

- ↑ Georg Pilk, The castle sites around the Wildenstein , in: Alfred Meiche, The castles and prehistoric homes of Saxon Switzerland , Dresden 1907, p. 314 ff.

- ↑ Christian Maaz: Winterstein - a critical analysis of historical sources. In: Castle research from Saxony. Issue 20 (2007), Deutsche Burgenvereinigung e. V., Landesgruppe Sachsen, p. 66.

- ↑ a b c Dietmar Heinicke (Ed.): Climbing Guide Saxon Switzerland. Volume Affensteine, Kleiner Zschand, Berg- & Naturverlag Rölke, Dresden 2002, p. 320.

- ↑ a b c Castles in Saxon Switzerland: Wildenstein Castle (rear robbery castle) (accessed on October 1, 2011).

- ↑ Axel Mothes: The journey is the goal. A foray over 50 lifts in Saxon Switzerland. Self-published, Halle / Saale 2005, p. 124.

- ↑ a b Irene Schmidt (Ed.): Hermann Krone. First photographic landscape tour of Saxon Switzerland. Verlag der Kunst, Dresden 1997, ISBN 90-5705-038-2 , p. 121.

- ^ Anne Müller, Matthias Weinhold: rock castles of Saxon Switzerland. Neurathen - Winterstein - Arnstein. Series of castles, palaces and defensive structures in Central Europe, Volume 23, Verlag Schnell and Steiner, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7954-2303-2 , p. 33.

- ^ Anne Müller, Matthias Weinhold: rock castles of Saxon Switzerland. Neurathen - Winterstein - Arnstein. Series of castles, palaces and fortifications in Central Europe, Volume 23, Verlag Schnell and Steiner, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7954-2303-2 , p. 29.

- ^ Matthias Mau: The rock castle Winterstein. Stiegenbuchverlag, Halle / Saale 2008, p. 21.

- ^ Anne Müller, Matthias Weinhold: The rock castle Winterstein. Reconstruction attempt based on the site findings. In: Castle research from Saxony. Issue 13 (2000), Deutsche Burgenvereinigung e. V., State Group Saxony, p. 17.

- ^ Matthias Mau: The rock castle Winterstein. Stiegenbuchverlag, Halle / Saale 2008, p. 41.

- ^ Anne Müller, Matthias Weinhold: The rock castle Winterstein. Reconstruction attempt based on the site findings. In: Castle research from Saxony. Issue 13 (2000), Deutsche Burgenvereinigung e. V., Landesgruppe Sachsen, p. 20.

- ^ Anne Müller, Matthias Weinhold: The rock castle Winterstein. Reconstruction attempt based on the site findings. In: Castle research from Saxony. Issue 13 (2000), Deutsche Burgenvereinigung e. V., Landesgruppe Sachsen, p. 22.

- ^ Anne Müller, Matthias Weinhold: The rock castle Winterstein. Reconstruction attempt based on the site findings. In: Castle research from Saxony. Issue 13 (2000), Deutsche Burgenvereinigung e. V., State Group Saxony, p. 23.

- ↑ a b c Anne Müller, Matthias Weinhold: rock castles of Saxon Switzerland. Neurathen - Winterstein - Arnstein. Series of castles, palaces and fortifications in Central Europe, Volume 23, Verlag Schnell and Steiner, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7954-2303-2 , p. 31.

- ^ A b Anne Müller, Matthias Weinhold: The rock castle Winterstein. Reconstruction attempt based on the site findings. In: Castle research from Saxony. Issue 13 (2000), Deutsche Burgenvereinigung e. V., State Group Saxony, p. 24.

- ^ Matthias Mau: The rock castle Winterstein. Stiegenbuchverlag, Halle / Saale 2008, p. 31.

- ^ Matthias Mau: The rock castle Winterstein. Stiegenbuchverlag, Halle / Saale 2008, p. 33.

- ^ Anne Müller, Matthias Weinhold: The rock castle Winterstein. Reconstruction attempt based on the site findings. In: Castle research from Saxony. Issue 13 (2000), Deutsche Burgenvereinigung e. V., Landesgruppe Sachsen, p. 25.

- ^ Anne Müller, Matthias Weinhold: The rock castle Winterstein. Reconstruction attempt based on the site findings. In: Castle research from Saxony. Issue 13 (2000), Deutsche Burgenvereinigung e. V., Landesgruppe Sachsen, p. 27.

- ^ Anne Müller, Matthias Weinhold: The rock castle Winterstein. Reconstruction attempt based on the site findings. In: Castle research from Saxony. Issue 13 (2000), Deutsche Burgenvereinigung e. V., Landesgruppe Sachsen, p. 30.

- ^ Alfred Neugebauer: The rock castle of the Recken vom Winterstein. In: Peter Rölke (Ed.): Hiking & Nature Guide Saxon Switzerland. Volume 1, Verlag Rölke, Dresden 1999, ISBN 3-934514-08-1 , p. 128.

- ^ A b Anne Müller, Matthias Weinhold: rock castles of Saxon Switzerland. Neurathen - Winterstein - Arnstein. Series of castles, palaces and fortifications in Central Europe, Volume 23, Verlag Schnell und Steiner, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7954-2303-2 , p. 34.

- ^ A b Matthias Mau: The rock castle Winterstein. Stiegenbuchverlag, Halle / Saale 2008, p. 51.

- ^ Anne Müller, Matthias Weinhold: rock castles of Saxon Switzerland. Neurathen - Winterstein - Arnstein. Series of castles, palaces and defensive structures in Central Europe, Volume 23, Verlag Schnell and Steiner, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7954-2303-2 , p. 35.

- ^ A b Matthias Mau: The rock castle Winterstein. Stiegenbuchverlag, Halle / Saale 2008, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Anne Müller, Matthias Weinhold: The rock castle Winterstein. Reconstruction attempt based on the site findings. In: Castle research from Saxony. Issue 13 (2000), Deutsche Burgenvereinigung e. V., Landesgruppe Sachsen, p. 35.

- ↑ a b c Anne Müller, Matthias Weinhold: rock castles of Saxon Switzerland. Neurathen - Winterstein - Arnstein. Series of castles, palaces and defensive structures in Central Europe, Volume 23, Verlag Schnell and Steiner, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7954-2303-2 , p. 36.

- ^ Anne Müller, Matthias Weinhold: The rock castle Winterstein. Reconstruction attempt based on the site findings. In: Castle research from Saxony. Issue 13 (2000), Deutsche Burgenvereinigung e. V., Landesgruppe Sachsen, p. 38.

- ^ Matthias Mau: The rock castle Winterstein. Stiegenbuchverlag, Halle / Saale 2008, p. 73.

- ↑ Peter Rölke (Ed.): Hiking & Nature Guide Saxon Switzerland. Volume 1, Verlag Rölke, Dresden 1999, ISBN 3-934514-08-1 , p. 130.